Published online Jan 14, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i2.303

Peer-review started: August 31, 2017

First decision: September 20, 2017

Revised: October 3, 2017

Accepted: October 26, 2017

Article in press: October 26, 2017

Published online: January 14, 2018

Processing time: 136 Days and 13.4 Hours

Primary benign schwannoma of the mesentery is extremely rare. To date, only 9 cases have been reported in the English literature, while mesenteric schwannoma with ossified degeneration has not been reported thus far. In the present study, we present the first giant ossified benign mesenteric schwannoma in a 58-year-old female. Ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging were used, but it was still difficult to determine the definitive location and diagnose the mass. By laparotomy, a 10.0 cm × 9.0 cm × 9.0 cm giant mass was found in the mesentery and was then completely resected. Microscopically, the tumour located in the mesentery mainly consisted of spindle-shaped cells with a palisading arrangement. Some areas of the tumour were ossified, and a true metaplastic bone formation was observed, with the presence of bone lamellae and osteoblasts. Immunohistochemical investigation of the tumour located in the mesentery showed that the staining for the S-100 protein was strongly positive, while the stainings of SMA, CD34, CD117 and DOG-1 were negative. The cell proliferation index, measured with Ki67 staining, was less than 3%. Finally, a giant ossified benign mesenteric schwannoma was diagnosed. After surgery, the patient was followed up for a period of 43 mo, during which she remained well, with no evidence of tumour recurrence.

Core tip: To date, only 9 cases of mesenteric schwannomas have been reported in the English literature; an ossified mesenteric schwannoma has not been reported. In the present study, we present the first giant ossified benign mesenteric schwannoma. It was challenging to determine the location and obtain a precise diagnosis of the mesenteric schwannoma prior to surgery. We completely resected the mesenteric schwannoma by laparotomy. In this paper, a literature review was conducted to deepen our understanding of mesenteric schwannomas.

- Citation: Wu YS, Xu SY, Jin J, Sun K, Hu ZH, Wang WL. Successful treatment of a giant ossified benign mesenteric schwannoma. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(2): 303-309

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i2/303.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i2.303

Schwannomas are mesenchymal neoplasms of the peripheral nerve sheath[1], which mainly develop in young to middle-aged patients with no obvious gender difference. Schwannomas are usually solitary sporadic lesions. About 3% occurred in patients with NF-2, 2% in those with schwannomatosis, and 5% in association with multiple meningiomas with or wthout NF2. Most of schwannomas, whether sporadic or inherited, display inactivating germline mutations of the tumour suppressor gene NF2 located on chromosome 22 which encodes the protein merlin or schwannomin[2]. This protein, localized to regions of the cell membrane engaged in cell contact and mobility, is expressed in Schwann cells, meningeal cells and the lens of the eye. The mechanism by which the loss of this protein results in tumorigenesis is not well understood. Schwannomas are usually benign (> 90%) and occupy approximately 5% of benign soft-tissue neoplasms[3,4]. The tumour can sometimes show secondary degenerative changes, including cyst formation, hyalinization, haemorrhage and calcification[5]. Schwannomas usually occur in the head, neck and extremities[6], while schwannomas in the bowel mesentery are extremely rare. To our knowledge, only nine cases of schwannomas located in the bowel mesentery have been reported[7-15]. In addition, mesenteric schwannoma with ossified degeneration has not been reported thus far. In the present study, we present the first giant ossified benign mesenteric schwannoma.

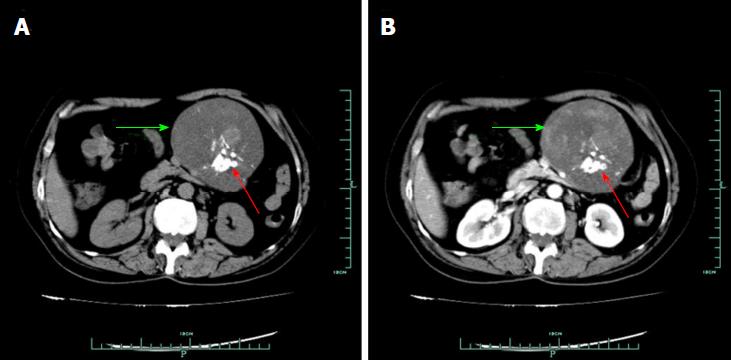

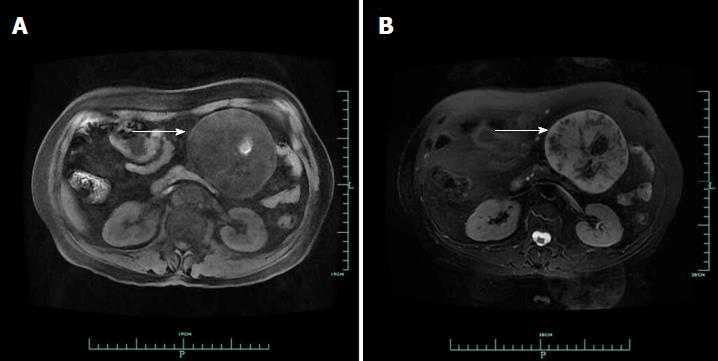

On January 14, 2014, a 58-year-old woman visited our department due to a lesion detected incidentally in her abdominal cavity during a routine health examination in the local hospital. On physical examination, a lesion was palpable in her upper left abdomen, sized 12 cm × 6 cm, and she felt slight tenderness. Four years previously, she had undergone resection of a lipoma in her back. Blood test findings, including tumour markers, were unremarkable. Ultrasound (US) revealed a solid lesion in the upper left abdomen, with clear margin, and also showed some cystic and strong echo areas in the lesion. Color doppler flow imagings (CDFIs) showed blood signals in the lesion. In a native computed tomography (CT) scan, the lesion in the upper left abdomen appeared well-defined and was 9.6 cm in diameter, while regions of high density were visible, compatible with calcification and/or ossification (Figure 1A). Contrast-enhanced CT study revealed a lesion with slight and inhomogeneous enhancement (Figure 1B). On T1-weighted images, the upper left abdominal lesion appeared hypointense, while appeared inhomogeneous and hyperintense on T2-weighted images (Figure 2). According to these imaging results, the abdominal lesion was primarily considered to be a teratoma.

After sufficient pre-surgical preparation, an exploratory laparotomy was performed. We found a giant mass originating from the mesentery and surrounded by a fibrous capsule. The territory of tumour blood supply was the branch of superior mesenteric artery. We carefully separated tissues around the tumour, ligated the vessels supplying the tumour and resected the tumour completely from the mesentery. Intraoperative frozen pathology revealed an ossified mesenteric schwannoma.

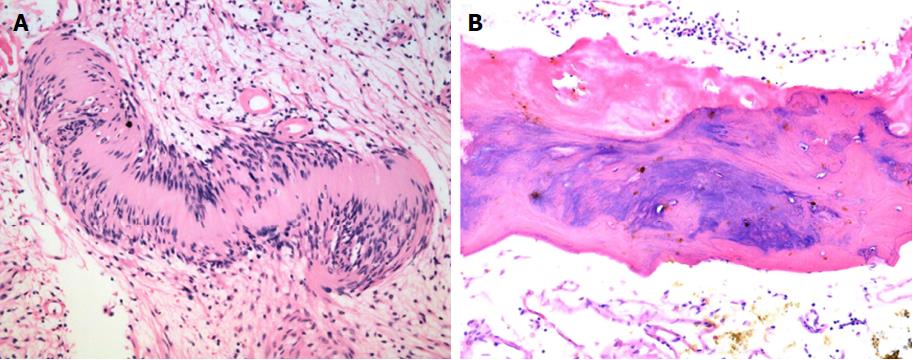

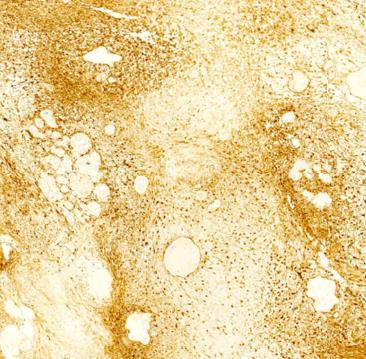

Macroscopically, the mass was 10.0 cm × 9.0 cm × 9.0 cm in size and yellowish-white in colour. Microscopically, in the mesenteric tumour, both hypercellular and hypocellular areas were visible. The tumour mainly consisted of spindle-shaped cells with a palisading arrangement; atypical cells or signs of malignancy were not observed (Figure 3A). Some areas of the tumour were ossified, and a true metaplastic bone formation could be seen, with the presence of bone lamellae and osteoblasts (Figure 3B). Immunohistochemical investigation of the tumour showed a strong positivity for S-100 protein (Figure 4), while SMA, CD34, CD117 and DOG-1 were negative. The cell proliferation index, measured with Ki67 staining, was less than 3%. Finally, a giant benign ossified mesenteric schwannoma was diagnosed. After surgery, the patient recovered smoothly and left the hospital 8 d later. She was followed up for a period of 43 mo, during which she was well, with no evidence of tumour recurrence during the follow-up time.

Schwannoma is an encapsulated tumour arising from Schwann cells[16]. Malignant peripheral sheath nerve tumours (MPNSTs) are uncommon and are always associated with von Recklinghausen’s disease[17]. Schwannomas mostly develop in young to middle-aged patients[18] and typically arise in the head, neck, and extremities[19]. The tumours in the ligament[20], mesentery[10] and intra-abdominal organs[21-23] are extremely rare. Secondary degenerative changes, including cyst formation, calcification, haemorrhage, and hyalinization, can sometimes be shown. However, mesenteric schwannoma with ossified degeneration has not been reported thus far, and to our knowledge, only nine cases of schwannomas in the bowel mesentery have been reported[7-15]. In the present study, we present a giant ossified benign mesenteric schwannoma. Brief clinical characteristics of ten cases of mesenteric schwannoma in the English-language literature, including our case, are outlined in Table 1 and the summarized clinical characteristics are present in Table 2. The mean age of these patients was 52.89 ± 12.89 years (range 38-80 years), and the male-female ratio was 4:5. Most patients were asymptomatic (70.00%). The mean tumour size was 8.86 ± 6.68 cm (range 2-22 cm). All of the tumours were benign.

| Ref. | Year | Sex/Age | Symptom | Imaging method | Size(cm) | Preoperative diagnosis | Treatment | Histology | Follow-up (mo) | Status |

| Present case | 2017 | F/58 | Asymptomatic | US, CT, MRI | 10 × 9 × 9 | Teratoma | Surgery | Benign | 43 | Survived |

| Medina-Gallardo et al[7] | 2017 | F/80 | Asymptomatic | CT | NA | NA | Laparoscopic operation | Benign | NA | NA |

| Tepox Padrón et al[8] | 2017 | F/38 | Asymptomatic | MRI | 11.3 × 8.4 × 4.1 | NA | Surgery | Benign | 24 | Survived |

| Wang et al[8] | 2014 | M/54 | Abdominal pain and hematochezia | CT, Colonoscopy | NA | NA | Ascending, transverse and splenic flexure colectomy | Benign | 12 | Survived |

| Tang et al[8] | 2014 | F/43 | Mild abdominal pain | CT | 4.0 × 4.0 × 1.9 | GIST or leiomyoma | Laparoscopic operation | Benign | 10 | Survived |

| Lao et al[8] | 2011 | M/45 | Asymptomatic | CT, MRI and Angiography | 2.2 × 1.7 | NA | Surgical excision | Benign | NA | NA |

| Kilicoglu et al[8] | 2006 | M/56 | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and constipation | US | 22 × 19 × 4 | Intra-abdominal mass | Surgery | Benign | 11 | Survived |

| Minami et al[8] | 2005 | F/54 | Asymptomatic | CT, MRI | 8.0 × 7.0 × 4.8 | Benign solid tumour | Enucleation | Benign | 5 | Survived |

| Ramboer et al[8] | 1998 | NA | Asymptomatic | MRI | NA | NA | NA | Benign | NA | NA |

| Murakami et al[8] | 1998 | M/48 | Asymptomatic | United States, CT, MRI | 4.5 × 4.0 × 4.0 | Benign solid tumour | Laparotomy | Benign | 24 | Survived |

| n (%) or mean ± SD (range) | |

| Age (yr) (n = 8) | |

| Mean | 52.89 ± 12.14 (38-80) |

| Sex (male/female), (male %) (n = 9) | 4/5 (44.44%) |

| Symptoms (n = 10) | |

| Asymptomatic | 7 (70.00) |

| Symptomatic | |

| Abdominal pain | 3 (30.00) |

| Hematochezia | 1 (10.00) |

| Nausea | 1 (10.00) |

| Vomiting | 1 (10.00) |

| Constipation | 1 (10.00) |

| Mean size (cm) (n = 7) | 8.86 ± 6.68 (2-22) |

| Operation (n = 9) | |

| Laparotomy | 6 (66.67) |

| Laparoscopic operation | 2 (22.22) |

| Enucleation | 1 (11.11) |

| Histology (n = 10) | |

| Benign | 10 (100.00) |

| Malignant | 0 (0.00) |

| Follow-up (mo) (n = 8) | 18.43 ± 12.00 (5-43) |

| Survived | 7 (100.00) |

Obtaining an accurate preoperative diagnosis of a mesenteric schwannoma prior to surgery is nearly impossible. The final diagnosis is based on the histo-pathological examinations of resected specimen[8]. Microscopically, these tumours present two morphologic features: Antoni type A areas and Antoni type B areas[24]. Antoni type A areas consist of closely packed spindle cells, with occasional nuclear palisading. Antoni type B areas are hypocellular and contain more mixoid tissue with high water content[18,25], which can be cystic, haemorrhagic, calcified and even ossified[5,24]. In the present study, some areas of the tumour were ossified, and a true metaplastic bone formation could be seen, with the presence of bone lamellae and osteoblasts, just as reported by Gurzu et al[26]. Schwannomas show strong immunoreactivity for S-100 protein, while CD34, CD117, DOG-1 and SMA are negative[27]. In all these cases, immunohistochemical staining is crucial to confirm the differentiation of the tumour cells. In the present study, the tumour located in the mesentery showed a strong positivity for S-100 protein, while SMA, CD34, CD117 and DOG-1 were negative. The cell proliferation index, measured with Ki67 staining, was less than 3%. Ki67 staining is potentially useful in distinguishing benign peripheral nerve sheath tumours from malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours, particularly in differentiating problematic cases of cellular schwannoma and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours. Ki-67 labelling indices ≥ 20% are highly predictive of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours[28]. The main differential diagnosis for schwannomas is gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs). GISTs are composed of spindled mesenchymal cells, which show a diffuse growth pattern and, frequently, positivity for CD34, CD117 and DOG-1[29]. Negative immunohistochemical staining for CD34, CD117 and DOG-1 can exclude the possibility of GIST.

Multiple imaging modalities, including US, CT, MRI, are helpful for establishing a probable diagnosis; however, an accurate preoperative diagnosis of the schwannoma is still difficult to obtain[9]. On US, schwannomas are usually well-defined hypodense lesions[12]. Plain CT scan shows a well-defined hypodense mass. Cystic, haemorrhagic, calcified and even ossified degeneration sometimes can be seen. On dynamic CT, Antoni A areas of schwannomas are typically well enhanced. Because of the loose stroma and low cellularity, schwannomas with Antoni B areas generally show low density and can be cystic[9,11]. On T1-weighted images, schwanommas appeared hypointense, while appeared inhomogeneous and hyperintense on T2-weighted images[14,30]. Celiac angiography is important to determine the arteries supplying the tumour[11]. Fine-needle aspiration cytology, accompanied by immunohistochemical staining, may play an important role in defining the appropriate treatment procedure and prognosis[31].

Surgery is curative for mesenteric schwannomas. In the present case, by laparotomy, a giant mass was found that had originated from the mesentery and was surrounded by a fibrous capsule. The patient was followed up for a period of 43 mo, during which she remained well, with no evidence of tumour recurrence.

In conclusion, a schwannoma located in the mesentery is extremely rare. To our knowledge, our study presents the tenth reported mesenteric schwannoma. In addition, a mesenteric schwannoma with ossified degeneration has not been reported thus far. In the present study, we present the first giant benign mesenteric schwannoma with ossified degeneration. It was difficult to acquire an accurate diagnosis of the mesenteric schwannoma preoperatively, because of the lack of specific symptoms, radiological characteristics and tumour markers.

A 58-year-old woman visited our department due to a lesion detected incidentally in her abdominal cavity during a routine health examination in the local hospital.

A lesion, palpable in the her upper left abdomen, was sized 12 cm × 6 cm, and she felt slight tenderness.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumour, intra-abdominal teratoma, sarcoma and neurogenic tumour.

Blood test findings, including tumour markers, were unremarkable.

Ultrasound revealed a solid lesion in the upper left abdomen, with clear margin, and also showed some cystic and strong echo areas in the lesion. Color doppler flow imagings (CDFIs) showed blood signals in the lesion. In a native computed tomography (CT) scan, the lesion in the upper left abdomen appeared well-defined and was 9.6 cm in diameter, while regions of high density were visible, compatible with calcification and/or ossification. Contrast-enhanced CT study revealed a lesion with slight and inhomogeneous enhancement. On T1-weighted images, the upper left abdominal lesion appeared hypointense, while appeared inhomogeneous and hyperintense on T2-weighted images (Figure 2). According to these imaging results, the abdominal lesion was primarily considered to be a teratoma.

Macroscopically, the mass was 10.0 cm × 9.0 cm × 9.0 cm in size and yellowish-white in colour. Microscopically, in the mesenteric tumour, both hypercellular and hypocellular areas were visible. The tumour mainly consisted of spindle-shaped cells with a palisading arrangement; atypical cells or signs of malignancy were not observed. Some areas of the tumour were ossified, and a true metaplastic bone formation could be seen, with the presence of bone lamellae and osteoblasts. Immunohistochemical investigation of the tumour showed a strong positivity for S-100 protein , while SMA, CD34, CD117 and DOG-1 were negative. The cell proliferation index, measured with Ki67 staining, was less than 3%. Finally, a giant benign ossified mesenteric schwannoma was diagnosed.

The authors completely resected the mass located in the mesentery by laparotomy.

Schwannomas in the bowel mesentery are extremely rare. To our knowledge, only 9 cases of schwannomas located in the bowel mesentery have been reported. In addition, mesenteric schwannoma with ossified degeneration has not been reported thus far.

In the present study, the authors present the first giant ossified benign mesenteric schwannoma. It was difficult to obtain an accurate diagnosis of the mesenteric schwannoma preoperatively, because of the lack of specific symptoms, radiological characteristics and tumour markers.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Lee CL, Lee WJ, Maruyama H, Serio G S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Le Guellec S. [Nerve sheath tumours]. Ann Pathol. 2015;35:54-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | J D, R S, K C, Devi NR. Pancreatic schwannoma - a rare case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:FD15-FD16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ariel IM. Tumors of the peripheral nervous system. CA Cancer J Clin. 1983;33:282-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pilavaki M, Chourmouzi D, Kiziridou A, Skordalaki A, Zarampoukas T, Drevelengas A. Imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors with pathologic correlation: pictorial review. Eur J Radiol. 2004;52:229-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Xu SY, Sun K, Xie HY, Zhou L, Zheng SS, Wang WL. Hemorrhagic, calcified, and ossified benign retroperitoneal schwannoma: First case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e4318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Das Gupta TK, Brasfield RD. Tumors of peripheral nerve origin: benign and malignant solitary schwannomas. CA Cancer J Clin. 1970;20:228-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Medina-Gallardo A, Curbelo-Peña Y, Molinero-Polo J, Saladich-Cubero M, De Castro-Gutierrez X, Vallverdú-Cartie H. Mesenteric intranodal schwannoma: uncommon case of neurogenic benign tumor. J Surg Case Rep. 2017;2017:rjx008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tepox Padrón A, Ramírez Márquez MR, Cordóva Ramón JC, Cosme-Labarthe J, Carrillo Pérez DL. Mesenteric schwannoma: an unusual cause of abdominal mass. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2017;109:76-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang QM, Jiang D, Zeng HZ, Mou Y, Yi H, Liu W, Zeng QS, Wu CC, Tang CW, Hu B. A case of recurrent intestinal ganglioneuromatous polyposis accompanied with mesenteric schwannoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:3126-3128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tang SX, Sun YH, Zhou XR, Wang J. Bowel mesentery (meso-appendix) microcystic/reticular schwannoma: case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1371-1376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lao WT, Yang SH, Chen CL, Chan WP. Mesentery neurilemmoma: CT, MRI and angiographic findings. Intern Med. 2011;50:2579-2581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kilicoglu B, Kismet K, Gollu A, Sabuncuoglu MZ, Akkus MA, Serin-Kilicoglu S, Ustun H. Case report: mesenteric schwannoma. Adv Ther. 2006;23:696-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Minami S, Okada K, Matsuo M, Hayashi T, Kanematsu T. Benign mesenteric schwannoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:1006-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ramboer K, Moons P, De Breuck Y, Van Hoe L, Baert AL. Benign mesenteric schwannoma: MRI findings. J Belge Radiol. 1998;81:3-4. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Murakami R, Tajima H, Kobayashi Y, Sugizaki K, Ogura J, Yamamoto K, Kumazaki T, Egami K, Maeda S. Mesenteric schwannoma. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:277-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Das Gupta TK, Brasfield RD, Strong EW, Hajdu SI. Benign solitary Schwannomas (neurilemomas). Cancer. 1969;24:355-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Móller Pedersen V, Hede A, Graem N. A solitary malignant schwannoma mimicking a pancreatic pseudocyst. A case report. Acta Chir Scand. 1982;148:697-698. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Xu SY, Wu YS, Li JH, Sun K, Hu ZH, Zheng SS, Wang WL. Successful treatment of a pancreatic schwannoma by spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:3744-3751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Abell MR, Hart WR, Olson JR. Tumors of the peripheral nervous system. Hum Pathol. 1970;1:503-551. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Bayraktutan U, Kantarci M, Ozgokce M, Aydinli B, Atamanalp SS, Sipal S. Education and Imaging. Gastrointestinal: benign cystic schwannoma localized in the gastroduodenal ligament; a rare case. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Liu LN, Xu HX, Zheng SG, Sun LP, Guo LH, Wu J. Solitary schwannoma of the gallbladder: a case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6685-6690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nishikawa T, Shimura K, Tsuyuguchi T, Kiyono S, Yokosuka O. Contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS of pancreatic schwannoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:463-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Xu SY, Guo H, Shen Y, Sun K, Xie HY, Zhou L, Zheng SS, Wang WL. Multiple schwannomas synchronously occurring in the porta hepatis, liver, and gallbladder: first case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e4378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tao L, Xu S, Ren Z, Lu Y, Kong X, Weng X, Xie Z, Hu Z. Laparoscopic resection of benign schwannoma in the hepatoduodenal ligament: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:3349-3353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Xu SY, Sun K, Xie HY, Zhou L, Zheng SS, Wang WL. Schwannoma in the hepatoduodenal ligament: A case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:10260-10266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gurzu S, Bara T, Bara T Jr, Jung I. Metaplastic bone formation in the abdominal wall--an incidental finding in a patient with gastric cancer. Case report and hypothesis about its histogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:844-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Weiss SW, Langloss JM, Enzinger FM. Value of S-100 protein in the diagnosis of soft tissue tumors with particular reference to benign and malignant Schwann cell tumors. Lab Invest. 1983;49:299-308. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Pekmezci M, Reuss DE, Hirbe AC, Dahiya S, Gutmann DH, von Deimling A, Horvai AE, Perry A. Morphologic and immunohistochemical features of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and cellular schwannomas. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:187-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kovecsi A, Jung I, Bara T, Bara T Jr, Azamfirei L, Kovacs Z, Gurzu S. First Case Report of a Sporadic Adrenocortical Carcinoma With Gastric Metastasis and a Synchronous Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor of the Stomach. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Xu SY, Sun K, Owusu-Ansah KG, Xie HY, Zhou L, Zheng SS, Wang WL. Central pancreatectomy for pancreatic schwannoma: A case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8439-8446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Domanski HA, Akerman M, Engellau J, Gustafson P, Mertens F, Rydholm A. Fine-needle aspiration of neurilemoma (schwannoma). A clinicocytopathologic study of 116 patients. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:403-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |