Published online Jan 14, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i2.290

Peer-review started: October 16, 2017

First decision: November 8, 2017

Revised: November 23, 2017

Accepted: November 28, 2017

Article in press: November 28, 2017

Published online: January 14, 2018

Processing time: 91 Days and 1.2 Hours

A 64-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with jaundice of the bulbar conjunctiva and general fatigue. After admission, she developed hepatic encephalopathy and was diagnosed with fulminant hepatitis based on the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) position paper. Afterwards, additional laboratory findings revealed that serum ceruloplasmin levels were reduced, urinary copper levels were greatly elevated and Wilson’s disease (WD)-specific routine tests were positive, but the Kayser-Fleischer ring was not clear. Based on the AASLD practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of WD, the patient was ultimately diagnosed with fulminant WD. Then, administration of penicillamine and zinc acetate was initiated; however, the patient unfortunately died from acute pneumonia on the 28th day of hospitalization. At autopsy, the liver did not show a bridging pattern of fibrosis suggestive of chronic liver injury. Here, we present the case of a patient with clinically diagnosed late-onset fulminant WD without cirrhosis, who had positive disease-specific routine tests.

Core tip: A 64-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with hepatopathy. After admission, she developed hepatic encephalopathy. Laboratory findings revealed that serum ceruloplasmin levels were reduced, serum and urinary copper levels were greatly elevated and Wilson’s disease (WD)-specific routine tests were positive. She was diagnosed with fulminant WD based on the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease practice guidelines. At autopsy, the liver did not show a bridging pattern of fibrosis suggestive of chronic liver injury. Here, we present the first case of a patient with clinically diagnosed late-onset fulminant WD without cirrhosis.

- Citation: Amano T, Matsubara T, Nishida T, Shimakoshi H, Shimoda A, Sugimoto A, Takahashi K, Mukai K, Yamamoto M, Hayashi S, Nakajima S, Fukui K, Inada M. Clinically diagnosed late-onset fulminant Wilson’s disease without cirrhosis: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(2): 290-296

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i2/290.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i2.290

Wilson’s disease (WD) was initially described by Kinnier Wilson in 1912 as a congenital copper metabolism disorder disease with autosomal recessive inheritance and obstructed copper metabolic pathways from hepatocytes to bile[1]. The gene responsible for WD is ATP7B on chromosome 13q14[2]. Additionally, it has been reported that WD is an infrequent cause of chronic liver disease, with an estimated incidence of 1 per 30000, and its heterozygote rates are approximately 1 in 90 people worldwide[3]. There are two types of WD-induced hepatic failure: acute onset type, in which patients often develop fulminant hepatitis; and chronic type, which gradually progresses to cirrhosis. Furthermore, WD is identified in less than 5% of acute hepatic failure patients worldwide and is particularly dominant in young females[4,5].

Kidneys of patients with fulminant WD may be protected from copper-mediated tubular damage until transplantation by performing plasmapheresis, hemofiltration and exchange transfusion, hemofiltration or dialysis. Nevertheless, this disease is fatal without urgent liver transplantation. However, early diagnosis is difficult because of a lack of disease-specific symptoms, such as a Kayser-Fleischer ring or neuro-symptoms[4,6]; however, there is typically histological evidence involving copper deposition and bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis[7].

A few reports of patients with late-onset fulminant WD in the elderly population exist; this population usually develops fulminant hepatitis from chronic liver disease or cirrhosis. Here, we report a patient with clinically diagnosed late-onset fulminant WD without cirrhosis, who had positive disease-specific routine tests.

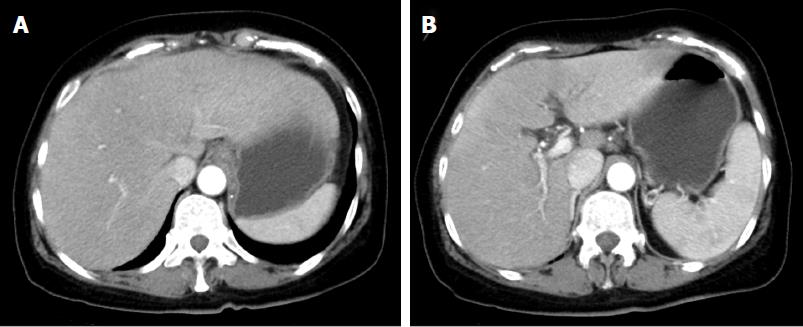

A 64-year-old woman became conscious of bulbar conjunctiva 2 d prior to admission. Afterwards, she was referred to our hospital with a low-grade fever and hepatopathy, complaining of jaundice of the bulbar conjunctiva and general fatigue, and she received emergency hospitalization. She had no medical history of drinking, consanguineous marriage, or oral use of dietary supplements, and her body mass index was 24. Regarding her family, her elder sister died from hepatic failure of unknown causes in her thirties. A physical examination showed normal abdominal findings and consciousness level, but her laboratory studies revealed abnormal liver function, including an elevated serum total bilirubin (T-Bil) level of 33.9 mg/dL [upper limit of normal (ULN): 1.2 mg/dL], direct bilirubin level of 25.5 mg/dL (ULN: 0.3 mg/dL) with an elevated ammonia (NH3) level of 143 μg/dL (ULN: 66 μg/dL), reduced serum prothrombin time of 19% (lower limit of normal: 70%) and anemia (hemoglobin, 6.1 g/dL) (Table 1). Contrast computerized tomography (CT) showed hepato-splenomegaly without mass lesion and dilatation of the hepatic duct in the liver (Figure 1). Based on these findings, she was diagnosed with acute hepatic failure on admission.

| Biochemical data | Fe, μg/dL | 130 | |

| WBC, /μL | 26200 | ferritin, ng/mL | 7817 |

| RBC, ×104/μL | 163 | IgG, mg/dL | 1678 |

| Hb, g/dL | 6.1 | IgM, mg/dL | 86 |

| Platelets, ×104/μL | 20.2 | IgA, mg/dL | 505 |

| MCV, fL | 122.7 | ANA | < 40 |

| MCH, pg | 37.4 | AMA-M2, index | 2 |

| MCHC, g/dL | 30.5 | sIL2-R, U/mL | 1130 |

| PT, % | 19 | Direct Coombs | - |

| PT-INR | 2.43 | Indirect Coombs | - |

| D-dimer, μg/mL | 1.8 | Vitamin B12, pg/mL | > 1500 |

| AST, U/L | 164 | Folic acid, ng/mL | 4 |

| ALT, U/L | 15 | Erythropoietin, IU/mL | 367 |

| LDH, U/L | 609 | Reticulocytes, % | 175 |

| ALP, U/L | 26 | Viral markers | |

| γGTP, U/L | 371 | HBsAg, IU/mL | 0.02 |

| Alb, g/dL | 2.3 | HBeAg, S/CO | < 0.5 |

| T-Bil, mg/dL | 33.99 | HBeAb, % | < 35 |

| D-Bil, mg/dL | 25.51 | HBcAb, S/CO | 0.23 |

| BUN, mg/dL | 36 | HBsAb, mIU/mL | 0 |

| Cr, mg/dL | 0.75 | HCVAb, S/CO | 0.1 |

| UA, mg/dL | 2.2 | CMV-IgM | 0.58 |

| Na, mEq/L | 133 | CMV-IgG | > 128 |

| K, mEq/L | 4.6 | EBV-IgM | < 10 |

| T-CHO, mg/dL | 83 | EBV-IgA | < 10 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 2.62 | EBV-IgG | 80 |

| NH3, μg/dL | 138 | HAVAb-IgM, S/CO | < 0.5 |

| Immunological and other data | HAVAb | < 0.4 | |

| Fe, μg/dL | 130 | HSV-CF | < 4 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 7817 |

After hospitalization, she was treated with transfusion of 6 fresh frozen plasma units. Her plasma was exchanged with 32 fresh frozen plasma units for 3 d under continuous hemofiltration because of anuria after 2 d in the hospital; however, her liver function did not recover. Furthermore, both hemoglobin and platelet levels gradually decreased with higher reticulocyte [175‰ (ULN: 20%)] and low levels of haptoglobin (below the scale, < 10 mg/dL), but both direct and indirect Coombs tests were negative. Based on these laboratory findings, we first diagnosed Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia with hepatic failure of unknown cause. Additional specific laboratory findings associated with acute hepatic failure did not suggest related causes, such as viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis or primary biliary cirrhosis (Table 1). Then, we attempted to perform a liver biopsy but were unsuccessful because of the progression of liver failure.

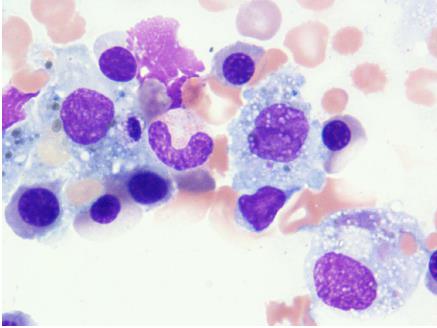

On day 4 of hospitalization, the patient progressed to a precoma stage with flapping tremor and confusion. On neurological examination, she fell into hepatic encephalopathy with greatly elevated NH3 levels (168 μg/dL). According to the 2014 American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) and European Association for study of the liver (EASL) guidelines[8], her hepatic encephalopathy was characterized as type A, overt, grade II, episodic, and precipitated. On day 5 of hospitalization, we performed bone marrow examination, which showed hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow and diagnosed the cause of pancytopenia. The Histiocyte Society HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria (available at http://www.histiocytesociety.org/) were fulfilled (Figure 2). Based on the AASLD position paper[9], we diagnosed acute hepatic failure as fulminant hepatitis with unidentified hemophagocytic syndrome.

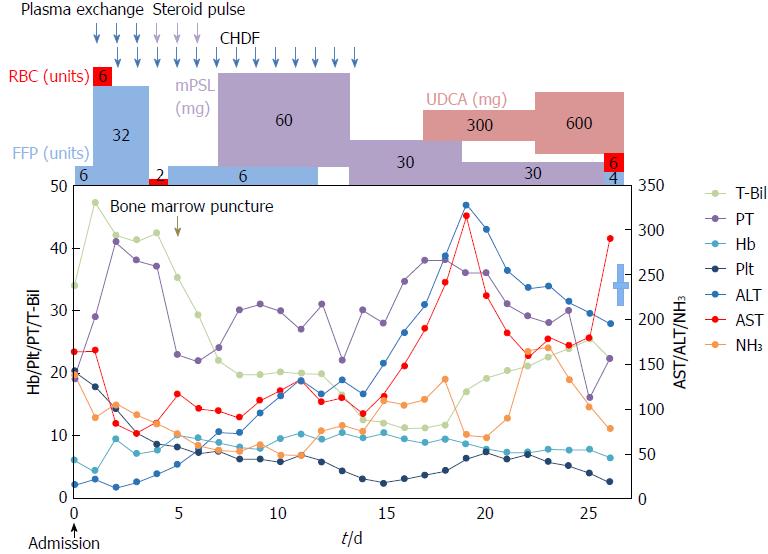

Figure 3 shows the time course of T-Bil, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), prothrombin time, hemoglobin, NH3 and platelets. Then, we performed steroid pulse therapy (methylprednisolone of 1 g/d, intravenously) for 3 d, followed by oral methylprednisolone (0.6 mg/kg). Then, steroids were tapered to 5 mg weekly. After steroid therapy, it was found that serum ceruloplasmin levels declined to 16.7 mg/dL and urinary copper levels were greatly elevated, up to 17900 μg/dL (895 μg/d); however, serum copper levels did not increase (105 μg/dL) and the Kayser-Fleischer ring was not clear. Based on the AASLD[7] and EASL clinical practice guidelines[3] for the diagnosis and treatment of WD, the patient met the diagnostic criteria for WD. From these findings, she was finally diagnosed fulminant WD.

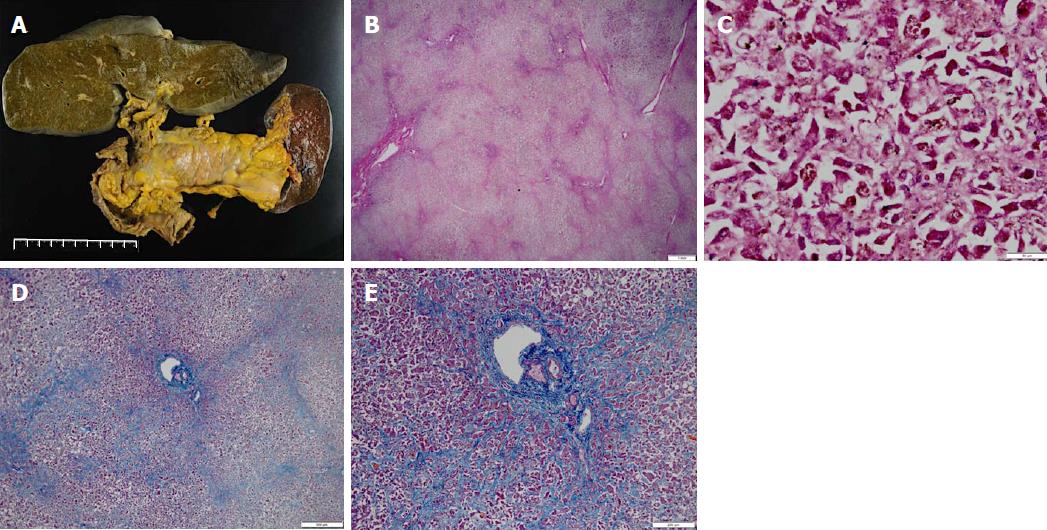

Then, administration of penicillamine (900 mg/d) and zinc acetate (150 mg/d) was started from a gastric tube on day 9 of hospitalization. Additionally, we considered liver transplantation; however, the patient died from hepatic failure with acute pneumonia on day 28 of hospitalization. We obtained approval from her family and then performed pathological anatomy. The liver (weight of 1580 g) was bile stained and soft (Figure 4A). The capsule was wrinkled. Microscopically, the liver showed massive necrosis and collapse of the intervening parenchyma (Figure 4B, C). Rhodanine staining unclearly depicted copper deposition in the scattered residual hepatocytes because of massive necrosis and collapse of the intervening parenchyma (not shown), and a bridging pattern of fibrosis suggestive of chronic liver injury was not found (Figure 4D, E). Histopathological examinations confirmed the diagnosis of fulminant hepatitis. Additionally, we obtained approval from her son and examined ATP7B on chromosome 13, but no genetic defect associated with WD was found. In summary, we here report a patient with sporadic, late-onset fulminant WD without cirrhosis.

WD is an autosomal recessive inherited disease with copper metabolism disorder in the liver that results in excessive copper deposition in many organs and tissues. Generally, WD is recognized as a slow, progressive chronic disease with young-onset in children or young adults, but age at onset of WD is widely variable. The presenting feature of WD is hepatic dysfunction, which is shown in more than half of patients. It develops as acute hepatitis involving three major patterns: (1) chronic active hepatitis; (2) cirrhosis, which is the most common initial presentation; and (3) fulminant hepatitis.

Most cases of WD develop in persons less than 40-years-old, and late-onset fulminant WD is quite rare. Some cases of patients who developed WD at over 40 years of age have been reported; however, the diagnosis of WD varied[10,11]. Ferenci et al[10] suggested that more attention is paid to the identification of older patients with WD. Almost all patients with fulminant WD died rapidly, without urgent liver transplantation over time; therefore, early diagnosis is necessary. However, the diagnosis of WD is quite difficult because clinical features of WD-like hepatic failure or neuropsychiatric disturbances vary widely and the clinical condition varies from asymptomatic states to fulminant hepatic failure[2]. If all available tests without genetic tests are applied, 20% of the cases in patients over 40 years old were missed[10,11]. There were several reasons why elderly WD subjects were overlooked due to diagnostic criteria limitations based on clinical symptoms and laboratory findings. Ferenci et al[10] also demonstrated that WD should be considered in patients presenting unidentified hepatic or neurologic disease. Increased awareness of WD and the use of a recently proposed diagnostic algorithm could lead to greater detection in elderly patients.

Recently, predictive markers for the diagnosis of WD-induced acute hepatic failure have been reported: reduced hemoglobin (< 10 g/dL), elevated serum copper levels (> 200 μg/dL), decreased ratios of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) to T-Bil (< 4) and elevated ratios of AST to ALT (> 2.2). The sensitivity/specificity of reduced hemoglobin and elevated serum copper levels was 94%/74% and 75%/96%, respectively. Additionally, the sensitivity/specificity of ALP to T-Bil ratio and AST to ALT ratio was 94%/96% and 94%/86%, respectively. Consequently, the combination of ALP to T-Bil ratio and AST to ALT ratio provided a diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of 100%[4]. In the present case, serum copper and hemoglobin on admission were 105 μg/dL and 6.1 g/dL, respectively. Unfortunately, we had a difficult time with early diagnosis, but disease-specific routine tests were positive in this case; the ratio of ALP to T-Bil was 1.3 and that of AST to ALT was 10.9. Screening for a diagnosis of WD in the setting of acute hepatic failure with ceruloplasmin measurements is generally unreliable. Disease-specific routine tests were useful to accurately distinguish WD patients with acute liver failure and were an acceptable and rapidly available alternative.

According to the AASLD practice guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of WD, classical diagnosis of WD includes recognition of corneal Kayser-Fleischer rings, identification of reduced concentrations of serum ceruloplasmin (< 20 mg/dL), and increased 24-h urine copper (> 40 μg/d), in addition to quantitative copper levels in percutaneous liver biopsy specimens (> 250 μg/g dry weight). In the present case, concentrations of serum ceruloplasmin and 24-h urine copper were 16.7 mg/dL and 895 μg/d, respectively. Although low serum levels of ceruloplasmin and high levels of cupriuria may be observed in acute liver failure due to other causes, we ruled out other acute liver injuries, such as viral infection, autoimmune and drug-induced hepatic damage, despite the possibility of other unknown hepatitis. In addition, all of the above predictive markers (reduced hemoglobin, elevated serum copper levels, decreased ratios of ALP to T-Bil and elevated ratios of AST to ALT) met the criteria for diagnosis of WD-induced acute hepatic failure. Hence, we reached a diagnosis of acute liver failure due to WD. We believe that WD-induced acute hepatic failure first developed, and then hemophagocytosis followed, which allowed hepatic failure to rapidly deteriorate without developing cirrhosis.

There are, however, limitations to our report of WD diagnosis. First, it was difficult to retrospectively weigh the precise copper levels in the liver because all liver tissues were fixed in formalin. Then, we evaluated copper deposition in the liver using rhodanine staining. We, however, believe that copper deposition was difficult to examine with rhodanine staining in the scattered residual hepatocytes because of massive necrosis and collapse of the intervening parenchyma. Some reports have suggested that immunohistochemistry staining is inadequate for examining copper deposition[12,13].

Liver biopsy is a useful method to confirm WD diagnosis and almost all patients with WD-induced acute hepatic failure have advanced fibrosis. However, no presence of bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis in the liver was found during autopsy in the present case. According to the AASLD and EASL clinical practice guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of WD, the patient ultimately met the diagnostic criteria, which are accurate in approximately 85% of cases with clinical symptoms and laboratory findings. In addition, genetic testing is necessary to diagnose WD. Unfortunately, gene testing was not performed on the patient due to her rapid clinical course, but her son was negative for the ATP7B gene by DNA analysis. However, it was reported that 13% of patients with WD did not have a mutation and 28.8% showed only one mutation[9]. Based on these reports and her clinical course, we diagnosed the patient with late-onset fulminant WD. To the best of our knowledge, the present case is the first report of a patient diagnosed with late-onset fulminant WD without cirrhosis, who had positive disease-specific routine tests.

A 64-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with jaundice of the bulbar conjunctiva and general fatigue.

A physical examination showed normal abdominal findings but Kayser-Fleischer ring was not clear. The authors first diagnosed hepatic failure of unknown cause.

Malignant tumors (hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma and metastatic tumors) and hepatic failure-related causes, such as viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis or primary biliary cirrhosis, drug-induced hepatic damage.

Laboratory studies revealed the diagnostic criteria for Wilson’s disease based on the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) and European Association for study of the liver (EASL) clinical practice guidelines; declined serum ceruloplasmin levels (16.7 mg/dL) and elevated urinary copper levels [17900 μg/dL (895 μg/d)], and Wilson’s disease-specific routine tests; reduced hemoglobin (6.1 g/dL), decreased ratios of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) to total bilirubin (T-Bil) (1.3) and elevated ratios of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (10.9).

Contrast computerized tomography (CT) showed hepato-splenomegaly without mass lesion and dilatation of the hepatic duct in the liver.

At autopsy, the liver did not show a bridging pattern of fibrosis suggestive of chronic liver injury.

Administration penicillamine and zinc acetate were started.

Regarding predictive markers for the diagnosis of Wilson’s disease-induced acute hepatic failure, the sensitivity/specificity of reduced hemoglobin, elevated serum copper levels, ALP to T-Bil ratio, AST to ALT ratio and the combination of ALP to T-Bil ratio were 94%/74%, 75%/96%, 94%/96%, 94%/86% and 100%, respectively.

To the best of our knowledge, the present case is the first report of a patient diagnosed with late-onset fulminant WD without cirrhosis who had positive disease-specific routine tests.

Generally, WD is recognized as a slow, progressive chronic disease with young-onset in children or young adults, but this case reports a patient with sporadic, late-onset fulminant WD without cirrhosis. In addition, predictive markers (reduced hemoglobin, elevated serum copper levels, decreased ratios of ALP to T-Bil and elevated ratios of AST to ALT) were useful in the diagnosis of WD.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Aizawa Y, Iorio R, Manesis EKK, Xie Q, Yalniz M S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Li RF

| 1. | Compston A. Progressive lenticular degeneration: a familial nervous disease associated with cirrhosis of the liver, by S. A. Kinnier Wilson, (From the National Hospital, and the Laboratory of the National Hospital, Queen Square, London) Brain 1912: 34; 295-509. Brain. 2009;132:1997-2001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rodriguez-Castro KI, Hevia-Urrutia FJ, Sturniolo GC. Wilson’s disease: A review of what we have learned. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:2859-2870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 3. | European Association for Study of Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Wilson’s disease. J Hepatol. 2012;56:671-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 971] [Cited by in RCA: 783] [Article Influence: 60.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Korman JD, Volenberg I, Balko J, Webster J, Schiodt FV, Squires RH Jr, Fontana RJ, Lee WM, Schilsky ML; Pediatric and Adult Acute Liver Failure Study Groups. Screening for Wilson disease in acute liver failure: a comparison of currently available diagnostic tests. Hepatology. 2008;48:1167-1174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiødt FV, Larson A, Davern TJ, Han SH, McCashland TM, Shakil AO, Hay JE, Hynan L. S. Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:947-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1562] [Cited by in RCA: 1462] [Article Influence: 63.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Roberts EA, Schilsky ML; Division of Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. A practice guideline on Wilson disease. Hepatology. 2003;37:1475-1492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Roberts EA, Schilsky ML; American Association for Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD). Diagnosis and treatment of Wilson disease: an update. Hepatology. 2008;47:2089-2111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 884] [Cited by in RCA: 813] [Article Influence: 47.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, Cordoba J, Ferenci P, Mullen KD, Weissenborn K, Wong P. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60:715-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1583] [Cited by in RCA: 1408] [Article Influence: 128.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Polson J, Lee WM; American Association for the Study of Liver Disease. AASLD position paper: the management of acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2005;41:1179-1197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 644] [Cited by in RCA: 642] [Article Influence: 32.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ferenci P, Członkowska A, Merle U, Ferenc S, Gromadzka G, Yurdaydin C, Vogel W, Bruha R, Schmidt HT, Stremmel W. Late-onset Wilson’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1294-1298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Weitzman E, Pappo O, Weiss P, Frydman M, Haviv-Yadid Y, Ben Ari Z. Late onset fulminant Wilson’s disease: a case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17656-17660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lindquist RR. Studies on the pathogenesis of hepatolenticular degeneration. II. Cytochemical methods for the localization of copper. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:370-379. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Pilloni L, Lecca S, Van Eyken P, Flore C, Demelia L, Pilleri G, Nurchi AM, Farci AM, Ambu R, Callea F. Value of histochemical stains for copper in the diagnosis of Wilson’s disease. Histopathology. 1998;33:28-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |