Published online Apr 21, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i15.1650

Peer-review started: November 29, 2017

First decision: December 13, 2017

Revised: December 20, 2017

Accepted: January 18, 2018

Article in press: January 18, 2018

Published online: April 21, 2018

Processing time: 141 Days and 22.3 Hours

To develop a scale of domains associated with the health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) in patients with cirrhosis-related ascites.

We initially undertook literature searches and a qualitative study in order to design a cirrhosis-associated ascites symptom (CAS) scale describing symptoms with a potential detrimental impact on health related quality of life (HRQL) (the higher the score, the worse the symptoms). Discriminatory validity was assessed in a validation cohort including cirrhotic patients with (1) tense/severe; (2) moderate/mild; or (3) no ascites (controls). Patients also completed chronic liver disease questionnaire (CLDQ) and the EuroQoL 5-Dimensions 5-Level (EQ-5D-5L) questionnaire evaluating HRQL. The relation between scale scores was analysed using Spearman correlations.

The final CAS scale included 14 items. The equivalent reliability was high (Chronbach’s alpha 0.88). The validation cohort included 103 patients (72% men, mean age 62.4 years). The mean scores for each question in the CAS scale were higher for patients with severe/tense ascites than for mild/moderate ascites and controls. Compared with controls (mean = 9.9 points), the total CAS scale score was higher for severe/tense ascites (mean = 23.8 points) as well as moderate/mild ascites (mean = 18.6 points) (P < 0.001 both groups). We found a strong correlation between the total CAS and CLDQ score (rho = 0.82, P < 0.001) and a moderate correlation between the CAS and the EQ-5D-5L score (0.67, P < 0.001).

The CAS is a valid tool, which reflects HRQOL in patients with ascites.

Core tip: This paper presents a newly generated cirrhosis-associated ascites symptom scale consisting of 14 items. The questionnaire addresses relevant questions of symptom burden of cirrhosis-associated ascites, takes only five minutes to complete and correlates strongly with chronic liver disease questionnaire score in patients with cirrhosis and ascites.

- Citation: Riedel AN, Kimer N, Jensen ASH, Dahl EK, Israelsen M, Aamann L, Gluud LL. Development and predictive validity of the cirrhosis-associated ascites symptom scale: A cohort study of 103 patients. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(15): 1650-1657

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i15/1650.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i15.1650

Ascites is a serious complication to cirrhosis[1,2]. Without liver transplantation, only about 55% of patients with cirrhosis and ascites are alive, five years after the initial diagnosis. In addition, the severity of symptoms associated with ascites may have a detrimental impact on health-related quality of life (HRQL). Five previous studies have evaluated the HRQL in patients with cirrhosis using generic questionnaires including the Medical Outcome Study Short Form 36 (SF-36), the Nottingham Health Profile and the Sickness Impact Profile[3-7]. All studies found that cirrhosis is associated with a detrimental effect on HRQL. None of the studies were designed to evaluate the association between ascites severity and the quality of life. However, one study found that disease progression, including development of ascites, is associated with an impaired HRQL[7]. Disease-specific questionnaires developed for the assessment of HRQL in patients with liver disease and cirrhosis have reached similar conclusions[8,9]. The questionnaires include aspects that are of particular relevance to patients with cirrhosis, such as concerns about complications and liver transplantation. The 29 item chronic liver disease questionnaire (CLDQ) was used to evaluate HRQL in 204 patients representing all stages of various liver diseases[10]. The scale correlates with the severity of the underlying liver disease and is also associated with active medical and psychiatric comorbidity. Liver failure, development of minimal hepatic encephalopathy, malnutrition, abdominal pain, fatigue, and anxiety may also affect HRQL[11,12].

None of previous studies specifically evaluated the association between the severity of ascites related symptoms and HRQL. However, it is likely that the severity of symptoms is important.

In clinical trials of medical interventions, HRQL as well as symptom management are important parameters in the assessment of intervention benefits and harms[4,5,13,14]. A study including 212 outpatients with cirrhosis found that the management of cirrhosis-related complications is associated with improved HRQOL assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study Form, SF-36 and CLDQ questionnaires. The study found that ascites as well as a decrease in haemoglobin and previous hepatic encephalopathy predicted the HRQOL[15].

We therefore developed and evaluated the predictive ability of a scale specifically made to assess symptoms related to cirhosis-associated ascites. We subsequently undertook a multicenter cohort study to evaluate the association between our scale and a disease specific scale (CLDQ) as well as a generic HRQL questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L).

The present study was conducted as a multi-center study, with participation of three university hospitals in Denmark: Copenhagen University Hospital Hvidovre, Odense University Hospital and Aarhus University Hospital. The study was approved by the Danish Data protection Agency, journal no: 04054, ID: AHH-2015-075.

The development of the cirrhosis-associated ascites symptom (CAS) scale included a literature review and a qualitative study to evaluate face and content validity as well as discriminatory ability.

We initially searched for previously validated scales in MEDLINE and EMBASE (‘ascites’ AND (‘quality of life [Mesh]’ OR ‘life quality’ OR ‘health-related quality of life’ OR ‘health related quality of life’ OR ‘symptoms’) AND (‘cirrhosis’ OR ‘end-stage liver disease’). The searches were combined with manual searches of reference lists in potentially relevant articles and conference proceedings. None of our searches identified questionnaires evaluating symptoms associated with ascites.

We then proceeded with a qualitative study. Initially, the study group and ten independent experts identified and listed what they believed were the most important symptoms with an expected negative impact on HRQL (six hepatologists and four nurses with clinical experience in the management of patients with ascites from Gastro Unit, medical division, Copenhagen University Hospital Hvidovre, were interviewed). In our selection of symptoms (domains), we decided that they should occur frequently or be severe enough to have substantial impact on daily function in order to be considered for our scale.

After the selection of domains, we first conducted open interviews followed by structured interviews of ten patients with cirrhosis and moderate (n = 4) or severe ascites (n = 6). The interviews took place in a quiet room in the hospital ward. The selected domains were initially presented and patients were asked to rate them (Supplementary Table 1) according to the patient’s perceived ‘importance’, on the extent to which the symptom had bothered them. Each patient was then asked to complete the preliminary questionnaire themselves and to answer a debriefing form with the questions: (1) How long did it take to complete the questionnaire? (2) Did you need assistance from others to fill out the questionnaire? (3) Did you find any items confusing or difficult to respond to (and if so, list the items)? (4) Did you find any items upsetting? (5) Were any important items missing? and (6) Do you have any additional comments?

We revised the questionnaire instrument based on the answers. One question, which patients found upsetting and two questions, which patients found to be irrelevant or unimportant were removed. Revisions were decided by consensus among investigators.

After the development of the questionnaire, we prospectively enrolled a validation cohort (known group comparison) consisting of patients with cirrhosis of any aetiology and (1) severe/tense ascites; (2) mild/moderate ascites; and (3) no ascites as determined through a combination of clinical assessments and abdominal ultrasound. All gave their informed consent to participate. Subjects were attending out-patient clinics or were admitted to hospital ward with ascites as their primary problem. Subjects with hepatic encephalopathy or other cognitive disability were excluded.

Subjects completed the following scales and questionnaires: (1) CAS scale; (2) Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire[9]; and (3) EQ-5D-5L questionnaire[16,17].

Statistics were calculated using STATA IC v14 R2 and GraphPad Prism v6. We used the Crohnbach’s alpha to assess equivalent reliability. We defined discriminant validity as the ability of the questionnaire to discriminate between the severity of ascites. Discriminant validity was evaluated using Dunnett’s test to adjust for multiple comparisons. The severe and mild ascites groups (assuming that this group has fewer and less severe symptoms than patients with severe ascites) were compared with the control group and P-values < 0.05 were considered significant. We originally planned to evaluate convergent validity with previously validated scales assessing symptoms or HRQOL associated with ascites. Since no previous scales were identified, we used the CLDQ and the EQ-5D-5L. We compared scale scores using Spearman correlation and included the (1) CAS scale; (2) CLDQ; (3) CLDQ subscale parameters; and (4) EQ-5D-5L. The CLDQ subscale parameters are defined domains consisting of specific questions in the CLDQ questionnaire. These domains include fatigue, emotional function, worry, activity, abdominal symptoms and systemic symptoms[9].

Correlations higher than 0.70 were considered strong and values below 0.40 were interpreted as poor.

The final scale included 14 items (Table 1). Chronbach’s alpha was 0.88 for the total score, which we considered as acceptable. The validation cohort included 103 patients.

| Please answer the following questions with a cross or tick with regards to how you have felt in the past four weeks. | |||||

| Nej | Sjældent | Indimellem | Ofte | ||

| No | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | ||

| 1 | Har du ondt i maven? | ||||

| Do you have stomach ache? | |||||

| 2 | Har du ømhed i maven? | ||||

| Does your stomach feel sore? | |||||

| 3 | Har du kvalme? | ||||

| Do you feel nauseous? | |||||

| 4 | Har du madlede? | ||||

| Do you feel an aversion for food? | |||||

| 5 | Har du nedsat appetit? | ||||

| Do you experience a loss of appetite? | |||||

| 6 | Har du ændret afføring? | ||||

| Have you experienced a change in your stool? | |||||

| 7 | Har du følt dig utilpas? | ||||

| Have you felt uncomfortable? | |||||

| 8 | Er du træt? | ||||

| Are you tired? | |||||

| 9 | Har du åndenød? | ||||

| Do you experience a shortness of breath? | |||||

| 10 | Har du svært ved at trække vejret helt igennem? | ||||

| Do you feel troubled when breathing deeply? | |||||

| 11 | Har du svært ved at få tøj eller sko på? | ||||

| Are you disabled when dressing or putting on shoes? | |||||

| 12 | Har du svært ved at komme rundt derhjemme? | ||||

| Do you experience difficulties in mobility at home? | |||||

| 13 | Har du svært ved at gå? | ||||

| Do you experience trouble walking? | |||||

| 14 | Har du ondt i benene? | ||||

| Do your legs hurt? | |||||

Demographic data are stated in Table 2. Seventy-four were male (72%) and mean age was 62.4 years (range 38-85). The proportion of patients with Child Pugh A was 24%, Child Pugh B: 58% and Child Pugh C: 19%. Forty-four percent had severe/tense ascites and 27% had mild/moderate ascites. A control group of 31 patients (30%) had no ascites.

| Control group, no ascites (n = 31) | Mild/moderate (n = 27) | Tense (n = 45) | Total (n = 103) | |

| Age: mean (SD) | 61.5 (8.4) | 62.3 (10.2) | 63.1 (11.3) | 62.4 (10.1) |

| Gender: Males | 23 (74) | 19 (70) | 32 (71) | 74 (72) |

| Etiology | ||||

| Alcohol | 28 (90) | 22 (81) | 38 (86) | 88 (86) |

| Viral | 1 (3) | 2 (7) | 3 (7) | 6 (6) |

| Alcohol and viral | 1 (3) | 1 (4) | 3 (7) | 5 (5) |

| Other | 3 (10) | 4 (15) | 6 (13) | 13 (13) |

| MELD score: mean (SD) | 10.1 (3.3) | 14.8 (6.2) | 15.9 (6.3) | 13.8 (6.0) |

| Child PUGH: mean (SD) | 6.2 (1.8) | 8.1 (1.3) | 9.1 (1.4) | 7.9 (1.9) |

| Class A | 19 (61) | 4 (15) | - | 23 (22) |

| Class B | 7 (23) | 17 (63) | 27 (60) | 51 (50) |

| Class C | 2 (6) | 2 (7) | 12 (27) | 16 (16) |

| Laboratory values (SD) | ||||

| Hemoglobin (mmol/L) | 8.4 (1.4) | 7.1 (1.2) | 6.4 (1.4) | 7.2 (1.6) |

| White blood cells (× 109/L) | 6.9 (2.6) | 7.2 (3.9) | 7.3 (3.5) | 7.1 (3.3) |

| Platelets (mmol/L) | 145 (65) | 158 (95) | 160 (87) | 155 (83) |

| Albumin (g/L) | 35 (5.8) | 29 (5.9) | 30 (14) | 31 (10) |

| Cogulation factor II, VII, X (INR) | 1.3 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.3) | 1.5 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.4) |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 74 (17) | 87 (29) | 94 (48) | 86 (37) |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 138 (3.6) | 134 (5.9) | 132 (6.9) | 135 (6.3) |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.1 (0.4) | 4.3 (0.5) | 4.2 (0.7) | 4.2 (0.6) |

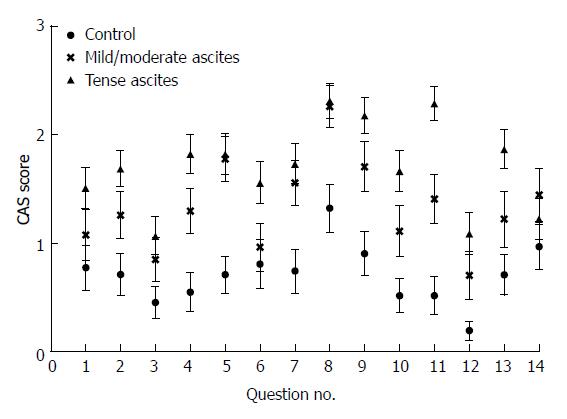

The mean scores for each question in the CAS scale suggested that symptoms were worse for patients with severe/tense ascites than for controls (Figure 1).

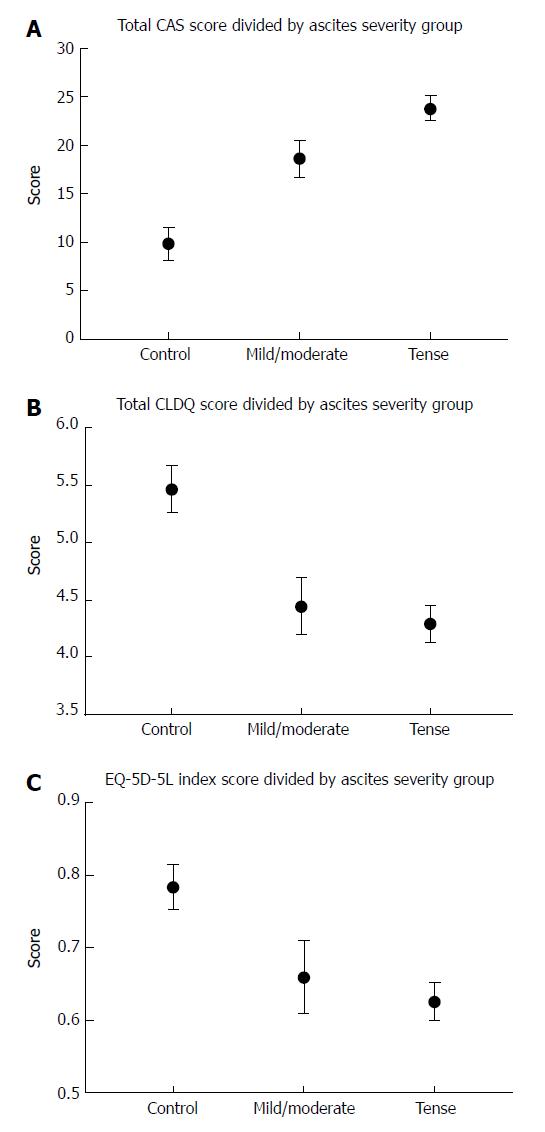

Symptoms also appeared worse for patients with mild/moderate ascites. Accordingly, the CAS scale score found that patients with severe/tense ascites or moderate/mild ascites had significantly worse scores compared with controls (P < 0.001 and P < 0.001; Figure 2).

As expected, patients with severe/tense ascites had the worst symptoms scores. Based on the CLDQ questionnaire, tense/severe ascites had a detrimental impact on HRQOL compared with controls (P < 0.001) as did moderate/mild ascites (P = 0.002). The EQ-5D-5L also found a lower HRQOL in patients with severe/tense ascites (P = 0.002) or moderate/mild ascites (P = 0.038).

We found a strong correlation between the CAS and the CLDQ total score (Spearman’s rho = 0.82, P < 0.001) as well as the CLDQ subscores; fatigue (0.78, P < 0.001), activity (0.81, P < 0.001) and systemic symptoms (0.77, P < 0.001) (Table 3). The CAS correlation with the generic scale (EQ-5D-5L) was moderate (0.67, P < 0.001).

We found that the developed CAS scale is effective in discriminating between various severities of ascites. It takes five minutes to perform and is easily implemented in daily practice. Moreover the CAS scale correlates strongly with the well-developed liver disease-specific HRQL instrument, CLDQ[9]. This suggests that our symptom assessment scale reflects the perceived HRQL of patients with cirrhosis and ascites. The CLDQ subparameters: fatigue, activity and systemic symptoms were likewise strongly correlated with the CAS scale suggesting that these domains are influential symptoms or functional limitations for patient with ascites. Surprisingly, the subparameter abdominal symptoms was not associated with the CAS scale. This may be due to use of words or inaccuracy of the questions, and will need further investigations for clarification. The total CLDQ was better correlated with CAS than each subparameter. This may be due to the impact of low quality of life affecting all aspects of life, allowing a total low score higher statistical significance. The CAS versus EQ-5D-5L correlation was moderate. The EQ-5D-5L is a generic scale which aims at examining non-disease specific HRQL[16,18,19], and specific symptoms related to cirrhosis and ascites may be undetected by this questionnaire. On the contrary, the CLDQ is created for patients with chronic liver disease, and it includes questions concerning ascites related symptoms and gains a stronger correlation with the CAS score.

To our knowledge, no previous study has developed and validated a questionnaire specifically aimed at evaluating HRQL in patients with ascites. However, previous literature describes correlations between disease severity in chronic liver disease and HRQL[7,12,20]. One study found that ascites had significant effects on self-related disease progression in cirrhosis[7]. Another showed that ascites was not a predictor for HRQL[12] and two studies found that management of ascites may improve HRQL[15,21]. In a study evaluating the impact of the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (SF-36) on HRQL in 523 patients with cirrhosis and ascites, a strong association between the physical component score (PCS) and leg edema, history of previous hepatic encephalopathy, severe ascites and low serum sodium levels were found[22]. The PCS includes questions on physical role, physical functioning, and body pain and general health. Also, a lower mental component score in the SF-36 was associated with low levels of serum sodium and treatment with lactulose. Hence, several factors influence HRQL when measured by SF36 and the impact of ascites was not clearly established by this study.

The CAS score comprises only 14 questions with high compliance to answering, takes only five minutes to complete and is readily implemented in daily clinic. The present study supports the results implying correlation between ascites severity and HRQL assuming that the CAS scale is valid and reliable. Progression in liver disease (e.g., measured by Child Pugh score which includes presence of ascites) is associated with ascites severity grade. This argues that our results support previous literature finding a correlation between liver disease severity and HRQL.

Our study has some considerable weaknesses. The relatively small sample size is one of the main limitations. Moreover, the majority of patients had cirrhosis due to alcohol. Dependency of alcohol, concomitant diseases related to alcohol use or cirrhosis that may impact physical health was not assessed in our cohort. Malnutrition is a serious complication to cirrhosis with impact on HRQL[23]. Also, impact of socioeconomic factors may influence quality of life substantially[24,25]. Future studies may address the synergy between various factors affecting quality of life in cirrhosis and ascites. The CAS scale is a specific scale evaluating the impact of symptoms related to ascites. When assessing overall quality of life on chronic liver disease or the impact of multi-morbidity in cirrhosis; validated and recommended scores such as SF36 or CLDQ should be used, with the CAS scale as a supplement[9]. Consequently, CAS scale validation also requires further research on larger sample size and applied on standardized groups of subjects. An interesting study setup would be to test the CAS scale on patients with cirrhosis presented with ascites before and after treatment. Further, the CAS scale ought to be tested as a monitoring tool for efficacy in intervention trials, compared with CLDQ and SF-36 questionnaires.

In conclusion, the present construction and validation of the CAS scale seems promising for future research in the area of ascites symptom management and HRQL. Initially the scale requires testing in other study setups in order to clarify the quality and practicability of the questionnaire. In future perspectives an optimized and/or further validated version of the CAS scale can be used as a monitoring tool in interventional trials and to assess the effects of standardized treatment. Ultimately the CAS scale can contribute to gaining further knowledge on how to treat ascites effectively and consequently improve patients’ quality of life.

Cirrhosis is associated with a detrimental effect on health related quality of life (HRQL). Disease-specific questionnaires have been developed for the assessment of HRQL in patients with liver disease and cirrhosis. The questionnaires include aspects that are of particular relevance to patients with cirrhosis, such as concerns about complications and liver transplantation.

No previous studies have specifically evaluated the association between the severity of ascites related symptoms and HRQL. However, it is likely that the severity of symptoms is important.

We therefore developed and evaluated the predictive ability of a symptom assessment scale specifically made to assess symptoms related to cirhosis-associated ascites. We subsequently undertook a multicenter cohort study to evaluate the association between our scale and a disease specific scale (CLDQ) as well as a generic HRQL questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L).

Development of the cirrhosis-associated ascites symptom (CAS) scale included a literature review, and a qualitative study to evaluate face and content validity as well as discriminatory ability. We initially searched for previously validated scales in MEDLINE and EMBASE. The searches were combined with manual searches of reference lists in potentially relevant articles and conference proceedings. We then proceeded with a qualitative study, where ten independent experts identified and listed what they believed were the most important symptoms with an expected negative impact on HRQL. Symptoms should occur frequently or be severe enough to have substantial impact on daily function in order to be considered for our scale.

We then conducted open interviews followed by structured interviews of ten patients with cirrhosis and moderate (n = 4) or severe ascites (n = 6). The selected domains were initially presented and patients were asked to rate them according to the patient’s perceived ‘importance’, on the extent to which the symptom had bothered them.

We revised the questionnaire instrument based on the answers.

After the development of the questionnaire, we prospectively enrolled a validation cohort consisting of patients with cirrhosis of any aetiology and severe, moderate or no ascites. All gave their informed consent to participate.

Subjects completed the following scales and questionnaires: CAS scale; Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire; and EQ-5D-5L questionnaire.

We used the Crohnbach’s alpha to assess equivalent reliability. Discriminant validity was evaluated using Dunnett’s test to adjust for multiple comparisons. We originally planned to evaluate convergent validity with previously validated scales assessing symptoms or HRQOL associated with ascites. Since no previous scales were identified, we used the CLDQ and the EQ-5D-5L. We compared scale scores using Spearman correlation and included the CAS scale, CLDQ, CLDQ subscale parameters, and EQ-5D-5L. Correlations higher than 0.70 were considered strong and values below 0.40 were interpreted as poor.

The final scale included 14 items. Chronbach’s alpha was 0.88 for the total score, which we considered as acceptable. The validation cohort included 103 patients.

The proportion of patients with Child Pugh A was 24%, Child Pugh B: 58% and Child Pugh C: 19%. Fourty-four percent had severe ascites and 27 percent had moderate ascites. A control group of 30 percent had no ascites. The mean scores for each question in the CAS scale suggested that symptoms were worse for patients with severe ascites than for controls. The CAS scale score found that patients with severe ascites or moderate ascites had significantly worse scores compared with controls. Based on the CLDQ questionnaire, severe ascites had a detrimental impact on HRQOL compared with controls as did moderate ascites. The EQ-5D-5L also found a lower HRQOL in patients with severe or moderate ascites. We found a strong correlation between the CAS and the CLDQ total score as well as the CLDQ subscores; fatigue, activity and systemic symptoms.

This study has developed and tested a symptom assessment scale for the impact of ascites in cirrhosis. The CAS scale is easy to use and correlates well with more extensive QoL questionnaires.

This study has brought focus to the impact and importance of effective management of ascites in chronic liver disease.

The CAS scale should be tested in larger clinical and interventional trials, preferably in combination with CLDQ or other generic health related quality of life questionnaires.

The CAS scale should be tested in larger cohorts with various etiologies for chronic liver disease and ascites, also in malignant ascites. The CAS scale should also be tested in interventional trials in which the effect of a given intervention on the CAS scale is evaluated, to demonstrate whether the CAS scale is applicable as a monitoring tool in ascites.

The authors would like to thank the health care professionals at the Gastro Unit, Copenhagen University Hospital Hvidovre, who participated in the qualitative study, thereby contributing to the design of the CAS scale. We also wish to thank medical professor Per Bech and senior doctor Finn Zierau for valuable feedback on statistical issues.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Denmark

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Jarcuska P, Jin B, Maruyama M, Niu ZS, Shimizu Y S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Ginès P, Cárdenas A, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Management of cirrhosis and ascites. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1646-1654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 546] [Cited by in RCA: 482] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ginés P, Quintero E, Arroyo V, Terés J, Bruguera M, Rimola A, Caballería J, Rodés J, Rozman C. Compensated cirrhosis: natural history and prognostic factors. Hepatology. 1987;7:122-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 760] [Cited by in RCA: 710] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Haraguchi M, Miyaaki H, Ichikawa T, Shibata H, Honda T, Ozawa E, Miuma S, Taura N, Takeshima F, Nakao K. Glucose fluctuations reduce quality of sleep and of life in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatol Int. 2017;11:125-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Maharshi S, Sharma BC, Sachdeva S, Srivastava S, Sharma P. Efficacy of Nutritional Therapy for Patients With Cirrhosis and Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in a Randomized Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:454-460.e3; quiz e33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Prasad S, Dhiman RK, Duseja A, Chawla YK, Sharma A, Agarwal R. Lactulose improves cognitive functions and health-related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis who have minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2007;45:549-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 412] [Cited by in RCA: 397] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Navasa M, Forns X, Sánchez V, Andreu H, Marcos V, Borràs JM, Rimola A, Grande L, García-Valdecasas JC, Granados A. Quality of life, major medical complications and hospital service utilization in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 1996;25:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Marchesini G, Bianchi G, Amodio P, Salerno F, Merli M, Panella C, Loguercio C, Apolone G, Niero M, Abbiati R; Italian Study Group for quality of life in cirrhosis. Factors associated with poor health-related quality of life of patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:170-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Häuser W, Schnur M, Steder-Neukamm U, Muthny FA, Grandt D. Validation of the German version of the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:599-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Younossi ZM, Guyatt G, Kiwi M, Boparai N, King D. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 1999;45:295-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 478] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Häuser W, Holtmann G, Grandt D. Determinants of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic liver diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:157-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ahluwalia V, Heuman DM, Feldman G, Wade JB, Thacker LR, Gavis E, Gilles H, Unser A, White MB, Bajaj JS. Correction of hyponatraemia improves cognition, quality of life, and brain oedema in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2015;62:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Thiele M, Askgaard G, Timm HB, Hamberg O, Gluud LL. Predictors of health-related quality of life in outpatients with cirrhosis: results from a prospective cohort. Hepat Res Treat. 2013;2013:479639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ong JP, Oehler G, Krüger-Jansen C, Lambert-Baumann J, Younossi ZM. Oral L-ornithine-L-aspartate improves health-related quality of life in cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy: an open-label, prospective, multicentre observational study. Clin Drug Investig. 2011;31:213-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sidhu SS, Goyal O, Mishra BP, Sood A, Chhina RS, Soni RK. Rifaximin improves psychometric performance and health-related quality of life in patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy (the RIME Trial). Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:307-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Les I, Doval E, Flavià M, Jacas C, Cárdenas G, Esteban R, Guardia J, Córdoba J. Quality of life in cirrhosis is related to potentially treatable factors. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:221-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Linde L, Sørensen J, Ostergaard M, Hørslev-Petersen K, Hetland ML. Health-related quality of life: validity, reliability, and responsiveness of SF-36, 15D, EQ-5D [corrected] RAQoL, and HAQ in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1528-1537. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Søgaard R, Christensen FB, Videbaek TS, Bünger C, Christiansen T. Interchangeability of the EQ-5D and the SF-6D in long-lasting low back pain. Value Health. 2009;12:606-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | EuroQol Group. EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10083] [Cited by in RCA: 11521] [Article Influence: 329.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen M, Kind P, Parkin D, Bonsel G, Badia X. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1727-1736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4003] [Cited by in RCA: 6516] [Article Influence: 465.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Younossi ZM, Boparai N, Price LL, Kiwi ML, McCormick M, Guyatt G. Health-related quality of life in chronic liver disease: the impact of type and severity of disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2199-2205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bhanji RA, Carey EJ, Watt KD. Review article: maximising quality of life while aspiring for quantity of life in end-stage liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:16-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Solà E, Watson H, Graupera I, Turón F, Barreto R, Rodríguez E, Pavesi M, Arroyo V, Guevara M, Ginès P. Factors related to quality of life in patients with cirrhosis and ascites: relevance of serum sodium concentration and leg edema. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1199-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rojas-Loureiro G, Servín-Caamaño A, Pérez-Reyes E, Servín-Abad L, Higuera-de la Tijera F. Malnutrition negatively impacts the quality of life of patients with cirrhosis: An observational study. World J Hepatol. 2017;9:263-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bajaj JS, Wade JB, Gibson DP, Heuman DM, Thacker LR, Sterling RK, Stravitz RT, Luketic V, Fuchs M, White MB. The multi-dimensional burden of cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy on patients and caregivers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1646-1653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Scalone L, Fagiuoli S, Ciampichini R, Gardini I, Bruno R, Pasulo L, Lucà MG, Fusco F, Gaeta L, Del Prete A. The societal burden of chronic liver diseases: results from the COME study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2015;2:e000025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |