Published online Mar 28, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i12.1353

Peer-review started: January 31, 2018

First decision: February 24, 2018

Revised: March 2, 2018

Accepted: March 18, 2018

Article in press: March 18, 2018

Published online: March 28, 2018

Processing time: 54 Days and 17.7 Hours

To analyze the safety and efficiency of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens in liver-transplanted patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) reinfection.

Between January 2014 and December 2016, 39 patients with HCV reinfection after liver transplantation were treated at our tertiary referral center with sofosbuvir (SOF)-based regimens, including various combinations with interferon (IFN), daclatasvir (DAC), simeprivir (SIM) and/or ledipasvir (LDV). Thirteen patients were treated with SOF + IFN ± RBV. Ten patients were treated with SOF + DAC ± RBV. Fiveteen patients were treated with fixed-dose combination of SOF + LDV ± RBV. One patient was treated with SOF + SIM + RBV. Three patients with relapse were retreated with SOF + LDV + RBV. The treatment duration was 12-24 wk in all cases. The decision about the HCV treatment was made by specialists at our transplant center, according to current available or recommended medications.

The majority of patients were IFN-experienced (29/39, 74.4%) and had a history of hepatocellular carcinoma (26/39, 66.7%) before liver transplantation. Sustained virological response at 12 wk (SVR12) was achieved in 10/13 (76.9%) of patients treated with SOF + IFN ± RBV. All patients with relapse were treated with fixed-dose combination of SOF + LDV + RBV. Patients treated with SOF + DAC + RBV or SOF + LDV + RBV achieved 100% SVR12. SVR rates after combination treatment with inhibitors of the HCV nonstructural protein (NS)5A and NS5B for 24 wk were significantly higher, as compared to all other therapy regimens (P = 0.007). Liver function was stable or even improved in the majority of patients during treatment. All antiviral therapies were safe and well-tolerated, without need of discontinuation of treatment or dose adjustment of immunosuppression. No serious adverse events or any harm to the liver graft became overt. No patient experienced acute cellular rejection during the study period.

Our cohort of liver-transplanted patients achieved high rates of SVR12 after a 24-wk course of treatment, especially with combination of NS5A and NS5B inhibitors.

Core tip: We examined the safety and efficiency of novel direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) in liver-transplanted patients with recurrence of hepatitis c virus (HCV) infection in a real-world cohort at our tertiary care center. In conclusion, DAAs are safe and very efficient in HCV patients after liver transplantation, even in case of recurrent cirrhosis or history of relapse after pegylated-interferon therapy. The high sustained virological response rates in our cohort, despite many patients with recurrent cirrhosis, may argue for a 24-wk therapy period in patients with risk factors for therapy failure in a posttransplant setting.

- Citation: Rupp C, Hippchen T, Neuberger M, Sauer P, Pfeiffenberger J, Stremmel W, Gotthardt DN, Mehrabi A, Weiss KH. Successful combination of direct antiviral agents in liver-transplanted patients with recurrent hepatitis C virus. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(12): 1353-1360

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i12/1353.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i12.1353

Recurrent infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) following liver transplant (LT) treatment is the leading cause of liver graft loss and death in liver-transplanted patients infected with HCV[1]. In patients with detectable HCV RNA at the time of transplantation, HCV universally recurs. In such cases, HCV infection shows an accelerated course, with progression to advanced fibrosis within 5 years post LT in the majority of patients. Fundamental steps in understanding and deciphering the HCV replication system in the last 2 decades has opened up the way for development of highly effective new antiviral drugs[2-4].

Before introduction of the direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapies, treatment options for recurrent HCV in liver-transplanted patients were limited, due to significant drug-drug interactions and severe side effects. The approval of DAAs has revolutionized HCV treatment. Nowadays, well-tolerated, interferon (IFN)-free and highly efficient treatment options are available for HCV-infected patients[5-8]. In most cases, DAA administration before liver transplantation prevents HCV recurrence[9].

Despite the growing number of successfully treated patients, HCV recurrence after orthotopic LT remains one of the most challenging clinical situations[10-12]. Thus, analysis of real-world cohorts of LT recipients may provide valuable insights into the safety and efficacy of DAA treatment in these cohorts[13-17]. Herein, we present the first experience of liver-transplanted patients with HCV recurrence at our tertiary care center.

The study cohort comprised all liver-transplanted patients treated with a DAA regimen at the Heidelberg University Hospital. In total, 39 patients were included. The baseline characteristics are depicted in Table 1. All patients included in the study were treated with DAAs. All patients were at least 6-mo post LT before the antiviral therapy was started. In all patients, corticosteroids had been discontinued successfully, by tapering over a 3-mo to 6-mo period and immunosuppressive therapy reduced to a long-term dosage. Immunosuppression was achieved by cyclosporine in 19 (48.7%) patients, tacrolimus in 18 (46.2%) patients, and sirolimus 1 (2.6%) or everolimus in 1 (2.6%) patient, respectively. Comedication with mycophenolate mofetil was administered in 21 (53.8%) patients. Patients with a history of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) before liver transplantation accounted for 26 (66.7%). All patients with HCC before LT met the Milan-criteria. Three patients [3 (7.7%)] have been already retransplanted at least once. The study covered the period from January 2014 to December 2016. The outcomes of all patients in the study were followed until June 2017.

| Characteristic | Data | |

| Sex | Male | 28 (71.8) |

| Female | 11 (28.2) | |

| Age (yr) | 58.6 (range: 45.8-72.3) | |

| Immunosuppression | Cyclosporine | 19 (48.7) |

| Tacrolimus | 18 (46.2) | |

| Sirolimus | 1 (2.6) | |

| Everolimus | 1 (2.6) | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 21 (53.8) | |

| Liver histology | F0-2 | 7 (17.9) |

| F3 | 15 (38.5) | |

| F4 | 17 (43.6) | |

| Liver function, CTP | A | 17 (43.6) |

| B | 2 (5.1) | |

| Risk factors | Interferon-experienced | 29 (74.4) |

| History of HCC | 26 (66.7) | |

| HCV genotype | 1 | 24 (61.5) |

| 2 | 1 (2.6) | |

| 3 | 13 (33.3) | |

| 4 | 1 (2.6) | |

HCV treatment was administered by the outpatient clinic at our tertiary center. The decision about the HCV treatment was made by specialists at our transplant center, according to current available or recommended medications. Patients were treated according to recommendations of available drugs that carried approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Evaluation Agency. As different drugs became approved during the course of this study, the therapy regimens were adapted. In the beginning, 400 mg sofosbuvir (SOF) was combined with pegylated (Peg)-IFN (180 µg once weekly, dosage modifications according manufacturers’ recommendations) and ribavirin (RBV). After introduction of 60 mg daclatasvir (DAC), 150 mg simeprivir (SIM) and fixed-dose combination of 400 mg SOF with 90 mg ledipasvir (LDV), IFN-containing regimens were no longer perpetuated.

Calculations were carried out using PASW Statistics 22. Frequencies were compared using a χ2 test or the Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate. Continuous data were compared using the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Written informed consent was obtained from each patient included in the study. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as reflected by the prior approval by the institution’s human research committee. The study was approved by the local ethics committee of Heidelberg University as well.

The baseline characteristics of the study cohort are presented in Table 1. The male to female ratio was 3:1. The median age at beginning of antiviral therapy was about 5 years above the median age of first liver transplantation (53.8 years; range: 23.4-68.4 years). Immunosuppression was achieved mainly by cyclosporine or tacrolimus, with only 2 of the patients receiving sirolimus or everolimus, respectively; half of the patients received comedication with mycophenolate mofetil.

Recurrent cirrhosis occurred in 17 (43.6%) patients, with the majority of cases having relatively low severity [Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score A] and 2 of the cases having mid-severity (CTP score B). Nearly two-thirds of the patients in the total study cohort were treatment experienced, with an IFN-containing regimen. 26 (66.7%) patients had a history of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) before liver transplantation. The median time since transplantation was 4.6 years, ranging from 5.5 mo to 22.7 years. The most common HCV genotypes were 1 and 3, respectively, with genotypes 2 and 4 being relatively rare. The median viral load before therapy was 1.43 × 106.

Nine patients were treated with SOF + RBV, five of who received the Peg-IFN combination therapy. In general, the treatment duration was 12 wk in cases of stable liver function and up to 24 wk in cases with known risk factors of therapy failure (e.g., recurrent cirrhosis or treatment-experience). One patient received SOF + RBV for 48 wk, as she was awaiting liver transplantation. Eighteen patients were treated with the fixed-dose combination of SOF plus LDV, either with (n = 15) or without (n = 3) RBV for 24 wk. Ten patients received SOF in combination with DAC, either with (n = 6) or without (n = 4) RBV for 24 wk. One patient was treated with a combination of SOF plus SIM and RBV for 24 wk (Table 2). Clinical and laboratory baseline characteristics were not different between the different regimen cohorts.

| n | Therapy | SVR24 |

| 5 | IFN + SOF + RBV | 4/5 (80.0%) |

| 8 | SOF + RBV | 6/8 (75.0%) |

| 9 | DAC +SOF + RBV | 9/9 (100.0%) |

| 1 | DAC + SOF | 1/1 (100.0%) |

| 13 | LDV + SOF + RBV | 13/13 (100.0%) |

| 2 | LDV + SOF | 2/2 (100.0%) |

| 1 | SIM + SOF + RBV | 1/1 (100.0%) |

All patients completed antiviral treatment. No serious adverse events occurred that required hospitalization or discontinuation of therapy. No adaption of immunosuppression was necessary during the course of treatment. No patient experienced acute cellular rejection of the graft during the study period. Side effects attributable to the antiviral therapy were fatigue (14/39, 35.9%), anemia (11/39, 28.2%) and irritability (6/39, 15.4%). Side effects concerning blood cell count were attributable to concomitant therapy with RBV. In patients without RVB therapy, no anemia or thrombocytopenia occurred. All side effects disappeared after therapy was finished.

At the end of the study period, all patients had attained Sustained virological response (SVR) at 24 wk (SVR24). Of the thirty-nine patients, three patients experienced relapse after the first therapy with SOF + RBV, including those with (n = 1) or without (n = 2) the Peg-IFN for 24 wk. Relapse occurred within 4 wk after the end of therapy. All patients with relapse were retreated with fixed-dose combination of SOF + LDV and achieved SVR24.

The viral loads detected during therapy are shown in Table 3. In the majority of patients HCV was undetectable between weeks 4 through 8 of the antiviral therapy. Only 2 patients had detectable viral load after 12 wk of treatment. In both of these cases, no HCV was detectable after 24 wk of treatment and no relapse occurred. There was no association between viral load at the beginning or during the course of therapy and risk for relapse.

| Time (wk) | Mean | Min | Max |

| T (0) | 3268770 | 45600 | 25200000 |

| T (4) | 25812.1 | 0 | 771000 |

| T (8) | 22.8 | 0 | 268 |

| T (12) | 4.1 | 0 | 101 |

| T (24) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

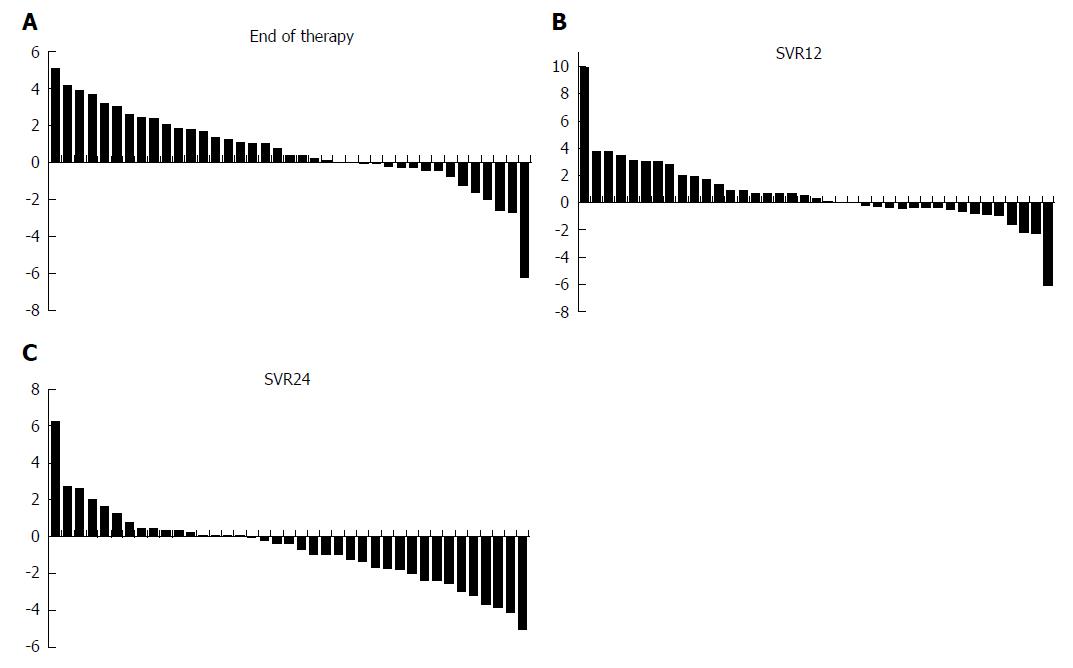

The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score remained stable or improved in 20 (51.3%) patients until the end of therapy. At 12 wk after end of therapy, improved or stable MELD score was found in 21 (53.8%) patients. At 24 wk after end of therapy, the majority of patients (32/39, 82.1%) had at least stable or improved MELD score (Figure 1).

We assessed several clinical and laboratory risk factors associated with treatment failure. We found no association of sex, age, immunosuppression, HCV genotype, viral load, CTP score or MELD score with treatment failure. In addition, there was no association found for any of these factors with SVR. When comparing different therapy regimens, we were able to demonstrate superior rates of SVR at 12 wk (SVR12) for a combination of inhibitors of the HCV nonstructural protein (NS)5A and NS5B administered for 24 wk, as compared to all other regimens (29/29 vs 10/13; P = 0.007).

During the study period, 1 patient underwent re-transplantation and 1 patient died because of progredient liver failure. Both had achieved SVR24 after successful antiviral therapy. During the study period, no HCC was detected in any patient, especially not in those who had had HCC before the LT. No other malignant disease became overt in our cohort during the study period.

The availability of new antiviral drugs poses new questions about the optimum timing and duration of treatment to prevent HCV recurrence after liver transplantation[18]. Facing good tolerance and low drug-drug interactions, antiviral treatment seems to be acceptable for both before and after transplantation[19-21]. Yet, antiviral therapy after liver transplantation remains challenging in this difficult-to-treat population[22,23]. On the one side, antiviral therapy should not interfere with immunosuppression; on the other side, stimulation of the immune system might compromise liver graft function. With the introduction of DAAs, a new era for treatment of HCV-infected patients has begun.

A growing amount of studies have confirmed the efficiency and safety of DAAs in LT recipients[24-26]. Several therapy regimens have been successfully tested so far[14]. We report here about the first experiences with liver-transplanted patients and HCV reinfection at our tertiary care center. To the end of the study period, all patients had reached SVR12. In this study we showed also SVR24 rates, to rule out the possibility of delayed relapse in our patients, like rarely seen in patients treated with interferon and ribavirin. As all three relapses to DAA therapy appeared already within 4 wk after cessation of therapy we believe SVR12 is sufficient to determine successful HCV eradication. We had decided on a 24-wk treatment period for the majority of patients, as most patients had already relapsed or shown nonresponse with past administered IFN-containing HCV therapies. Furthermore, most patients had already developed recurrent cirrhosis, representing another risk factor for therapy failure[27].

HCV therapy was well tolerated in all our patients, and there was no case of therapy termination necessitated for any patient due to side effects or adverse events. In our cohort, most patients received RBV in addition to the DAA[28]. Side effects concerning affectation of the blood count might be attributable to the comedication with RBV. Importantly, we recognized no serious harmful effects on transplant function, as no patient experienced an episode of acute cellular rejection or required re-transplantation during or immediately after the antiviral therapy. Most patients showed improvement of liver function after the end of therapy, which might improve graft survival in the future[29].

One patient underwent re-transplantation at 1 year after successful antiviral therapy, and another patient died due to progredient liver failure after more than 2 years after reaching SVR12. Both patients had recurrent cirrhosis and were transplanted more than 5 years ago. These patients might represent a subgroup of patients that have reached a point of no return, as HCV infection has already caused severe damage to the liver graft, which cannot be reverted even by successful antiviral therapy[29-32].

Liver function remained stable in most patients during the course of therapy and improved within 24 wk after end of therapy in more than 80% of patients. This is in line with other studies of posttransplant patients and emphasizes the importance of antiviral therapy for liver graft protection. Importantly, there was no HCC recurrence despite a high number of patients with HCC prior to transplantation in our cohort[33-35].

We were not able to identify any potential risk factors for therapy failure according to the clinical or laboratory parameters used in our study. In particular, we found no correlation with successful antiviral therapy and viral load, genotype, age, immunosuppression or liver function. Additionally, we found no different outcome between patients treated with RBV or without, which might underline the advantage of an RBV-free regimen[28]. When comparing different therapy regimens, we were able to demonstrate superior SVR12 rates for a combination of NS5A and NS5B inhibitors at 24 wk, as compared to all other regimens. However, this study was not designed nor powered to answer this question.

In conclusion, DAAs are safe and very efficient in HCV patients after liver transplantation, even in cases of recurrent cirrhosis or history of relapse after Peg-IFN therapy. The high SVR rates in our cohort, despite the many patients with recurrent cirrhosis, may argue for a 24-wk therapy period in patients with risk factors for therapy failure in a posttransplant setting.

Recurrent infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) following liver transplant (LT) treatment is the leading cause of liver graft loss and death in liver-transplanted patients infected with HCV. Before introduction of the direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapies, treatment options for recurrent HCV in liver-transplanted patients were limited, due to significant drug-drug interactions and severe side effects. The approval of DAAs has revolutionized HCV treatment.

Despite the growing number of successfully treated patients, HCV recurrence after orthotopic LT remains one of the most challenging clinical situations. Thus, analysis of real-world cohorts of LT recipients may provide valuable insights into the safety and efficacy of DAA treatment in these cohorts.

To analyze the safety and efficiency of DAA regimens in liver-transplanted patients with HCV reinfection in a real-world cohort.

The study cohort comprises all liver transplanted patients that were treated with direct acting antiviral regimen at the Heidelberg University Hospital from January 2014 to December 2016. In total 39 patients were included. Clinical and laboratory baseline characteristics were collected at entry into the study. All patients were at least six months liver transplanted before antiviral therapy was started. HCV treatment was administered by the outpatient clinic at our tertiary center. The decision about the HCV treatment was made by specialists at our transplant center, according to current available or recommended medication. Patients were treated according recommendations of available drugs after approval by FDA and EMEA. As different drugs were approved during the course of this study therapy regimen were adapted. In the beginning Sofosbuvir was combined with pegylated interferon (Peg-INF) and ribavirin. After introduction of Daclatasvir, Simeprivir and fixed-dose combination of Sofosbuvir with Ledipasvir interferon containing regimen were no longer perpetuated.

At the end of the study period, all thirty-nine patients had attained SVR at 24 wk (SVR24). Sustained virological response at 12 wk (SVR12) was achieved in 10/13 (76.9%) of patients treated with SOF + IFN ± RBV. All patients with relapse were treated with fixed-dose combination of SOF + LDV + RBV. Patients treated with SOF + DAC + RBV or SOF + LDV + RBV achieved 100% SVR12. SVR rates after combination treatment with inhibitors of the HCV nonstructural protein (NS)5A and NS5B for 24 wk were significantly higher, as compared to all other therapy regimens (P = 0.007). Liver function was stable or even improved in the majority of patients during treatment. All antiviral therapies were safe and well-tolerated, without need of discontinuation of treatment or dose adjustment of immunosuppression. No serious adverse events or any harm to the liver graft became overt. No patient experienced acute cellular rejection during the study period.

In conclusion, DAAs are safe and very efficient in HCV patients after liver transplantation, even in cases of recurrent cirrhosis or history of relapse after Peg-IFN therapy. The high SVR rates in our cohort, despite the many patients with rrecurrent cirrhosis, may argue for a 24-wk therapy period in patients with risk factors for therapy failure in a posttransplant setting.

HCV recurrence after orthotopic LT can be safely and efficiently treated with DAAs. Optimal timing and duration of antiviral therapy remains undetermined. Patients at risk for relapse need to be identified before initiation of therapy. Long-term effects of successful antiviral therapy, especially in patients with advanced recurrent cirrhosis, need to be analyzed in future.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P- Reviewer: Manolakopoulos S, Kanda T, Komatsu H, Sergi CM, Zhu X S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Goldberg D, Ditah IC, Saeian K, Lalehzari M, Aronsohn A, Gorospe EC, Charlton M. Changes in the Prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus Infection, Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis, and Alcoholic Liver Disease Among Patients With Cirrhosis or Liver Failure on the Waitlist for Liver Transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1090-1099.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 459] [Cited by in RCA: 469] [Article Influence: 58.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lohmann V, Körner F, Koch J, Herian U, Theilmann L, Bartenschlager R. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science. 1999;285:110-113. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Bartenschlager R, Lohmann V, Penin F. The molecular and structural basis of advanced antiviral therapy for hepatitis C virus infection. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:482-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 287] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lindenbach BD, Meuleman P, Ploss A, Vanwolleghem T, Syder AJ, McKeating JA, Lanford RE, Feinstone SM, Major ME, Leroux-Roels G. Cell culture-grown hepatitis C virus is infectious in vivo and can be recultured in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3805-3809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 362] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Weiler N, Zeuzem S, Welker MW. Concise review: Interferon-free treatment of hepatitis C virus-associated cirrhosis and liver graft infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:9044-9056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kwo PY, Mantry PS, Coakley E, Te HS, Vargas HE, Brown R Jr, Gordon F, Levitsky J, Terrault NA, Burton JR Jr, Xie W, Setze C, Badri P, Pilot-Matias T, Vilchez RA, Forns X. An interferon-free antiviral regimen for HCV after liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2375-2382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fontana RJ, Hughes EA, Bifano M, Appelman H, Dimitrova D, Hindes R, Symonds WT. Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir combination therapy in a liver transplant recipient with severe recurrent cholestatic hepatitis C. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:1601-1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Forns X, Charlton M, Denning J, McHutchison JG, Symonds WT, Brainard D, Brandt-Sarif T, Chang P, Kivett V, Castells L. Sofosbuvir compassionate use program for patients with severe recurrent hepatitis C after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2015;61:1485-1494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Curry MP, Forns X, Chung RT, Terrault NA, Brown R Jr, Fenkel JM, Gordon F, O‘Leary J, Kuo A, Schiano T, Everson G, Schiff E, Befeler A, Gane E, Saab S, McHutchison JG, Subramanian GM, Symonds WT, Denning J, McNair L, Arterburn S, Svarovskaia E, Moonka D, Afdhal N. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin prevent recurrence of HCV infection after liver transplantation: an open-label study. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:100-107.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Terrault NA, Berenguer M, Strasser SI, Gadano A, Lilly L, Samuel D, Kwo PY, Agarwal K, Curry MP, Fagiuoli S. International Liver Transplantation Society Consensus Statement on Hepatitis C Management in Liver Transplant Recipients. Transplantation. 2017;101:956-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fontana RJ, Brown RS Jr, Moreno-Zamora A, Prieto M, Joshi S, Londoño MC, Herzer K, Chacko KR, Stauber RE, Knop V, Jafri SM, Castells L, Ferenci P, Torti C, Durand CM, Loiacono L, Lionetti R, Bahirwani R, Weiland O, Mubarak A, ElSharkawy AM, Stadler B, Montalbano M, Berg C, Pellicelli AM, Stenmark S, Vekeman F, Ionescu-Ittu R, Emond B, Reddy KR. Daclatasvir combined with sofosbuvir or simeprevir in liver transplant recipients with severe recurrent hepatitis C infection. Liver Transpl. 2016;22:446-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Charlton M, Gane E, Manns MP, Brown RS Jr, Curry MP, Kwo PY, Fontana RJ, Gilroy R, Teperman L, Muir AJ, McHutchison JG, Symonds WT, Brainard D, Kirby B, Dvory-Sobol H, Denning J, Arterburn S, Samuel D, Forns X, Terrault NA. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for treatment of compensated recurrent hepatitis C virus infection after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:108-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Herzer K, Welzel TM, Spengler U, Hinrichsen H, Klinker H, Berg T, Ferenci P, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Inderson A, Zhao Y. Real-world experience with daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir ± ribavirin for post-liver transplant HCV recurrence and severe liver disease. Transpl Int. 2017;30:243-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kwok RM, Ahn J, Schiano TD, Te HS, Potosky DR, Tierney A, Satoskar R, Robertazzi S, Rodigas C, Lee Sang M. Sofosbuvir plus ledispasvir for recurrent hepatitis C in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2016;22:1536-1543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Welzel TM, Petersen J, Herzer K, Ferenci P, Gschwantler M, Wedemeyer H, Berg T, Spengler U, Weiland O, van der Valk M. Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir, with or without ribavirin, achieved high sustained virological response rates in patients with HCV infection and advanced liver disease in a real-world cohort. Gut. 2016;65:1861-1870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Beinhardt S, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Hofer H, Ferenci P. Interferon-free antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis C in the transplant setting. Transpl Int. 2015;28:1011-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chang CY, Nguyen P, Le A, Zhao C, Ahmed A, Daugherty T, Garcia G, Lutchman G, Kumari R, Nguyen MH. Real-world experience with interferon-free, direct acting antiviral therapies in Asian Americans with chronic hepatitis C and advanced liver disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fagiuoli S, Ravasio R, Lucà MG, Baldan A, Pecere S, Vitale A, Pasulo L. Management of hepatitis C infection before and after liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4447-4456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Coilly A, Roche B, Duclos-Vallée JC, Samuel D. Optimum timing of treatment for hepatitis C infection relative to liver transplantation. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:165-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Samur S, Kues B, Ayer T, Roberts MS, Kanwal F, Hur C, Donnell DMS, Chung RT, Chhatwal J. Cost Effectiveness of Pre- vs Post-Liver Transplant Hepatitis C Treatment With Direct-Acting Antivirals. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:115-122.e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Levitsky J, Verna EC, O‘Leary JG, Bzowej NH, Moonka DK, Hyland RH, Arterburn S, Dvory-Sobol H, Brainard DM, McHutchison JG. Perioperative Ledipasvir-Sofosbuvir for HCV in Liver-Transplant Recipients. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2106-2108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Charlton M, Curry MP, O‘Leary JG, Brown RS, Hunt S. Patient-reported outcomes with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus-related decompensated cirrhosis: an exploratory analysis from the randomised, open-label ASTRAL-4 phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:122-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ferenci P. Treatment of hepatitis C in difficult-to-treat patients. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:284-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Saxena V, Khungar V, Verna EC, Levitsky J, Brown RS Jr, Hassan MA, Sulkowski MS, O‘Leary JG, Koraishy F, Galati JS, Kuo AA, Vainorius M, Akushevich L, Nelson DR, Fried MW, Terrault N, Reddy KR. Safety and efficacy of current direct-acting antiviral regimens in kidney and liver transplant recipients with hepatitis C: Results from the HCV-TARGET study. Hepatology. 2017;66:1090-1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Vukotic R, Conti F, Fagiuoli S, Morelli MC, Pasulo L, Colpani M, Foschi FG, Berardi S, Pianta P, Mangano M. Long-term outcomes of direct acting antivirals in post-transplant advanced hepatitis C virus recurrence and fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis. J Viral Hepat. 2017;24:858-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Belli LS, Duvoux C, Berenguer M, Berg T, Coilly A, Colle I, Fagiuoli S, Khoo S, Pageaux GP, Puoti M. ELITA consensus statements on the use of DAAs in liver transplant candidates and recipients. J Hepatol. 2017;67:585-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ferenci P, Kozbial K, Mandorfer M, Hofer H. HCV targeting of patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:1015-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Pillai AA, Maheshwari R, Vora R, Norvell JP, Ford R, Parekh S, Cheng N, Patel A, Young N, Spivey JR. Treatment of HCV infection in liver transplant recipients with ledipasvir and sofosbuvir without ribavirin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:1427-1432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Habib S, Meister E, Habib S, Murakami T, Walker C, Rana A, Shaikh OS. Slower Fibrosis Progression Among Liver Transplant Recipients With Sustained Virological Response After Hepatitis C Treatment. Gastroenterology Res. 2015;8:237-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Young J, Weis N, Hofer H, Irving W, Weiland O, Giostra E, Pascasio JM, Castells L, Prieto M, Postema R. The effectiveness of daclatasvir based therapy in European patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced liver disease. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Vinaixa C, Strasser SI, Berenguer M. Disease Reversibility in Patients With Post-Hepatitis C Cirrhosis: Is the Point of No Return the Same Before and After Liver Transplantation? A Review. Transplantation. 2017;101:916-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zanetto A, Shalaby S, Vitale A, Mescoli C, Ferrarese A, Gambato M, Franceschet E, Germani G, Senzolo M, Romano A. Dropout rate from the liver transplant waiting list because of hepatocellular carcinoma progression in hepatitis C virus-infected patients treated with direct-acting antivirals. Liver Transpl. 2017;23:1103-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Cabibbo G, Petta S, Calvaruso V, Cacciola I, Cannavò MR, Madonia S, Distefano M, Larocca L, Prestileo T, Tinè F, Bertino G, Giannitrapani L, Benanti F, Licata A, Scalisi I, Mazzola G, Cartabellotta F, Alessi N, Barbàra M, Russello M, Scifo G, Squadrito G, Raimondo G, Craxì A, Di Marco V, Cammà C; Rete Sicilia Selezione Terapia - HCV (RESIST-HCV). Is early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV cirrhotic patients affected by treatment with direct-acting antivirals? A prospective multicentre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:688-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kanwal F, Kramer J, Asch SM, Chayanupatkul M, Cao Y, El-Serag HB. Risk of Hepatocellular Cancer in HCV Patients Treated With Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:996-1005.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 523] [Cited by in RCA: 684] [Article Influence: 85.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Beste LA, Green PK, Berry K, Kogut MJ, Allison SK, Ioannou GN. Effectiveness of hepatitis C antiviral treatment in a USA cohort of veteran patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;67:32-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |