Published online Mar 28, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i12.1312

Peer-review started: January 22, 2018

First decision: February 3, 2018

Revised: February 11, 2018

Accepted: February 26, 2018

Article in press: February 26, 2018

Published online: March 28, 2018

Processing time: 64 Days and 2.6 Hours

To investigate whether serum interleukin (IL)-34 levels are correlated with hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.

In this study, serum IL-34 levels were assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in 19 healthy controls and 175 patients with chronic HBV infection undergoing biopsy. The frequently used serological markers of liver fibrosis were based on laboratory indexes measured at the Clinical Laboratory of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University. Liver stiffness was detected by transient elastography with FibroTouch. The relationships of non-invasive makers of liver fibrosis and IL-34 levels with inflammation and fibrosis were analyzed. The diagnostic value of IL-34 and other liver fibrosis makers were evaluated using areas under the receiver operating characteristic curves, sensitivity and specificity.

Serum IL-34 levels were associated with inflammatory activity in the liver, and IL-34 levels differed among phases of chronic HBV infection (P = 0.001). By comparing serum IL-34 levels among patients with various stages of liver fibrosis determined by liver biopsy, we found that IL-34 levels ≥ 15.83 pg/mL had a high sensitivity of 86.6% and a specificity of 78.7% for identifying severe fibrosis (S3-S4). Furthermore, we showed that IL-34 is superior to the fibrosis-4 score, one of the serum makers of liver fibrosis, in identifying severe liver fibrosis and early cirrhosis in patients with HBV-related liver fibrosis in China.

Our results indicate that IL-34, a cytokine involved in the induction of activation of profibrogenic macrophages, can be an indicator of liver inflammation and fibrosis in patients with chronic HBV infection.

Core tip: Interleukin (IL)-34 is a cytokine involved in the induction of activation of profibrogenic macrophages, which is associated with the severity of liver fibrosis and inflammation. Numerous studies have shown that it has the potential to be a serological indicator of liver fibrosis and inflammation. We investigated the serum IL-34 levels in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection, and found the significance of serum levels of IL-34 as a serum target of liver fibrosis associated with chronic hepatitis B virus infection.

- Citation: Wang YQ, Cao WJ, Gao YF, Ye J, Zou GZ. Serum interleukin-34 level can be an indicator of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(12): 1312-1320

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i12/1312.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i12.1312

Liver fibrosis is a process accompanied by wound-healing responses caused by chronic injury and inflammation in the hepatic parenchyma, and it often results in serious complications, including portal hypertension and liver failure. It can lead to cirrhosis, which is identified as the final stage of liver fibrosis[1] and can even evolve into hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver fibrosis is often caused by viral infection, toxins and excess alcohol consumption, among others. Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is the most common cause of liver fibrosis in China[2].

Chronic HBV infection is characterized by progressive hepatic fibrosis and inflammation. In addition to the key role of hepatic stellate cells, the progression of liver fibrosis depends on the recruitment and accumulation of inflammatory monocytes, which can locally differentiate into macrophages, to the liver[3]. These macrophages activate hepatic stellate cells and promote and perpetuate fibrosis[4,5]. It has already been confirmed that interleukin (IL)-34 is a kind of macrophage differentiation factor that signals via the M-CSF receptor (c-fms or CD115)[6,7] and that its serum levels are elevated in hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected patients and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients with advanced liver fibrosis[3,8,9]. Although IL-34 has been identified as a profibrotic factor associated with chronic HCV infection-mediated fibrosis, data on the serum level and role of IL-34 in chronic HBV-infected patients are lacking.

The indication for antiviral therapy depends on HBV DNA levels, aminotransferase levels and/or the grade of inflammation and fibrosis determined by liver biopsy[10]. However, the extent of disease progression is often insufficiently reflected by aminotransferase levels; additionally, liver biopsy has substantial limitations because of the invasive nature of the process[11]. Up to 40% of patients are ineligible for liver biopsy[12]. Therefore, studies are investigating noninvasive methods for detecting fibrosis[13]. These methods rely on biomarkers that are easily determined using one or more serum indexes, such as aspartate transaminase (AST) to platelet ratio index (APRI), fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score, and fibrosis index (FI)[14]. Although these methods demonstrate adequate diagnostic performance, they still have some limitations. Liver stiffness, measured via transient elastography using FibroTouch, can be reliably used to detect fibrosis in most patients; however, this method cannot be used in patients with ascites or obesity, and its performance varies with operator experience[15].

In this study, we assessed the serum level of IL-34 in 175 chronic HBV-infected patients undergoing biopsy. We also analyzed the correlation between IL-34 and other serum indexes that reflect the extent of liver injury and inflammation and evaluated the possibility of using IL-34 level as a marker of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic HBV infection by comparing it with other assessment methods for liver fibrosis.

In total, 175 treatment-naive chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients who had undergone percutaneous liver biopsies at the Department of Infectious Diseases of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University from January 2014 to March 2016 were enrolled in this retrospective study. The inclusion criteria were age ≥ 16 years, history of HBV infection of more than 6 mo and positivity for hepatitis B surface antigen. The exclusion criteria were concomitant infection with the HCV or human immunodeficiency virus, history of antiviral therapy, compensated or decompensated liver cirrhosis, presence of alcoholic liver disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, autoimmune liver diseases, chronic liver diseases due to other causes and renal insufficiency, inadequate biopsy samples, and incomplete clinical data. Nineteen healthy subjects who gave blood on a voluntary basis served as controls, and written informed consent was obtained. This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Anhui Medical University. The study was performed in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Blood samples were collected at the time of patient presentation at our department, and serum was separated from blood samples by centrifugation. Serum IL-34 levels were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R and D Systems, United States).

Percutaneous liver biopsies were obtained using ultrasound-guided biopsy needles. The specimens were then fixed, paraffin-embedded and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. All liver tissues samples were evaluated by board-certified pathologists who were unaware of the patients’ clinical history. Liver fibrosis stages (S0-S4) were determined using the Scheuer’s classification system. The lack of fibrosis was characterized as S0, mild fibrosis as S1, moderate fibrosis as S2, severe fibrosis as S3-S4 and cirrhosis as S4.

Other laboratory parameters including AST, alanine transaminase (ALT), gamma-glutamyl transferase, alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels, platelet count and virological test results were routinely evaluated prior to liver biopsy at the Clinical Laboratory of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University.

Prior to liver biopsy, liver stiffness was determined using the FibroTouch instrument (Wuxi Hayes Kell Medical Technology Co. Ltd., China) operated by experienced technicians. Ten successful acquisitions were performed for each patient. The median value of the 10 measurements was used for analyses. Liver stiffness was expressed in kilopascals (kPa).

All statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc 15.8, GraphPad Prism 5.0 and SPSS 17.0. Differences between groups were tested using the Mann-Whitney U-test or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test (for continuous variables and nonparametric analyses for independent samples, respectively). Correlation coefficients (r) were calculated with nonparametric Spearman’s correlation analyses. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated for the assessment of scores predictive of stages of fibrosis. Area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity and specificity were calculated for each factor. The value with the best sensitivity and specificity in AUC analysis (Youden’s index) was chosen as the best cut-off. AUCs were compared using the approach described by Hanley and McNeil. P < 0.05 (two-sided) was considered significant.

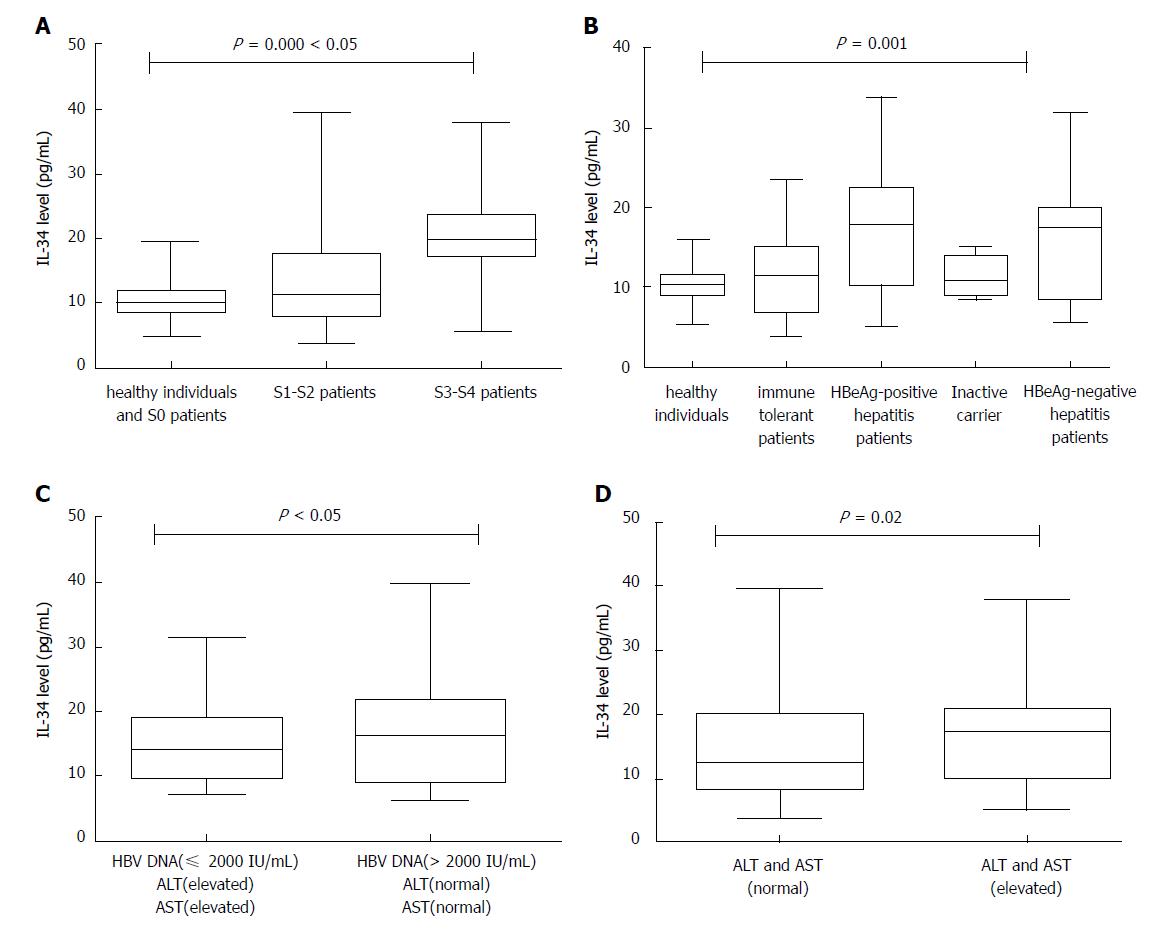

By investigating the serum levels of IL-34 in 19 healthy controls and 175 patients, we found that IL-34 levels were significantly different among the no fibrosis group (S0 patients and healthy subjects), mild to moderate fibrosis group (S1-S2), and advanced fibrosis group (S3-S4) (P = 0.000, Kruskal-Wallis test, two-tailed). The median expression level of IL-34 in S0 patients and healthy subjects was 10.05 pg/mL. The mean expression level of IL-34 was 11.53 pg/mL in S1-S2 patients, and the median increased to 19.84 pg/mL in S3-S4 patients (Table 1). We also found a highly statistically significant difference (P = 0.000, Kruskal-Wallis test, two-tailed) among HBV patients with different inflammation grades (Figure 1A).

| Stage | n | Median | 95%CI |

| S0 patients and healthy subjects | 34 | 10.05 | 9.28-11.27 |

| S1-S2 patients | 93 | 11.53 | 10.38-13.92 |

| S3-S4 patients | 67 | 19.84 | 17.34-20.63 |

Based on HBV DNA levels, hepatitis B envelope antigen (HBeAg) status and serum aminotransferase levels, patients were classified into four groups according to the European Association for the Study of the Liver guidelines: immune-tolerant patients (n = 26), HBeAg-positive hepatitis patients (n = 24), HBeAg-negative hepatitis patients (n = 40) and inactive carriers (n = 6)[10]. Furthermore, patients with HBeAg-negative status were stratified into two additional groups: patients with low-replicative hepatitis, characterized by low viral load (HBV DNA level ≤ 2000 IU/mL) and elevated aminotransferase levels (n = 13); and patients with high viral load (HBV DNA level > 2000 IU/mL) and normal aminotransferase levels (n = 26)[10].

Serum IL-34 levels were determined in patients and healthy individuals. Serum IL-34 concentrations ranged from 3.90 pg/mL to 39.56 pg/mL in HBV-infected patients and from 5.39 pg/mL to 15.78 pg/mL in healthy individuals. There were highly significant differences in serum IL-34 levels observed between these groups according to the Kruskal-Wallis test (P = 0.001) (Figure 1B). Patients with HBV infection had the highest IL-34 levels, followed by patients with HBeAg-negative or HBeAg-positive hepatitis. In contrast, inactive HBV carriers and immune-tolerant patients had the lowest IL-34 concentrations. Additionally, there were no differences in serum IL-34 levels among inactive HBV carriers, immune-tolerant patients and healthy individuals.

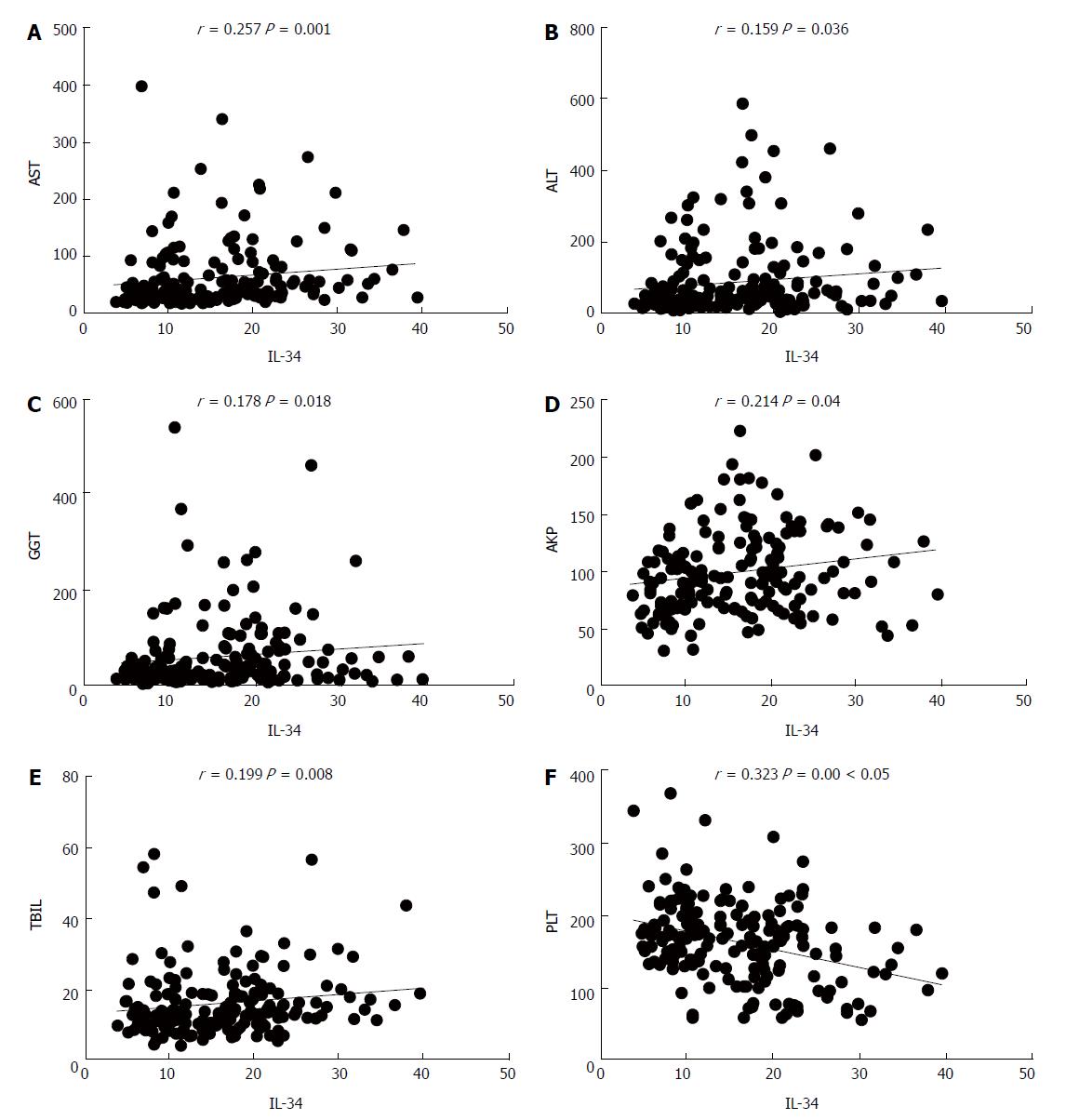

In patients with liver fibrosis (chronic HBV infection), there was a significant positive correlation between the serum levels of IL-34 and levels of ALT (r = 0.159, P = 0.036), AST (r = 0.257, P = 0.001), total bilirubin (r = 0.199, P = 0.008), indirect bilirubin (r = 0.225, P = 0.003), gamma-glutamyl transferase (r = 0.178, P = 0.018), alkaline phosphatase (r = 0.214, P = 0.004), and platelet count (r = -0.323, P = 0.000) (Figure 2). IL-34 levels were significantly higher in patients with elevated aminotransferase levels than in patients with normal aminotransferase levels (P = 0.02) (Figure 1C).

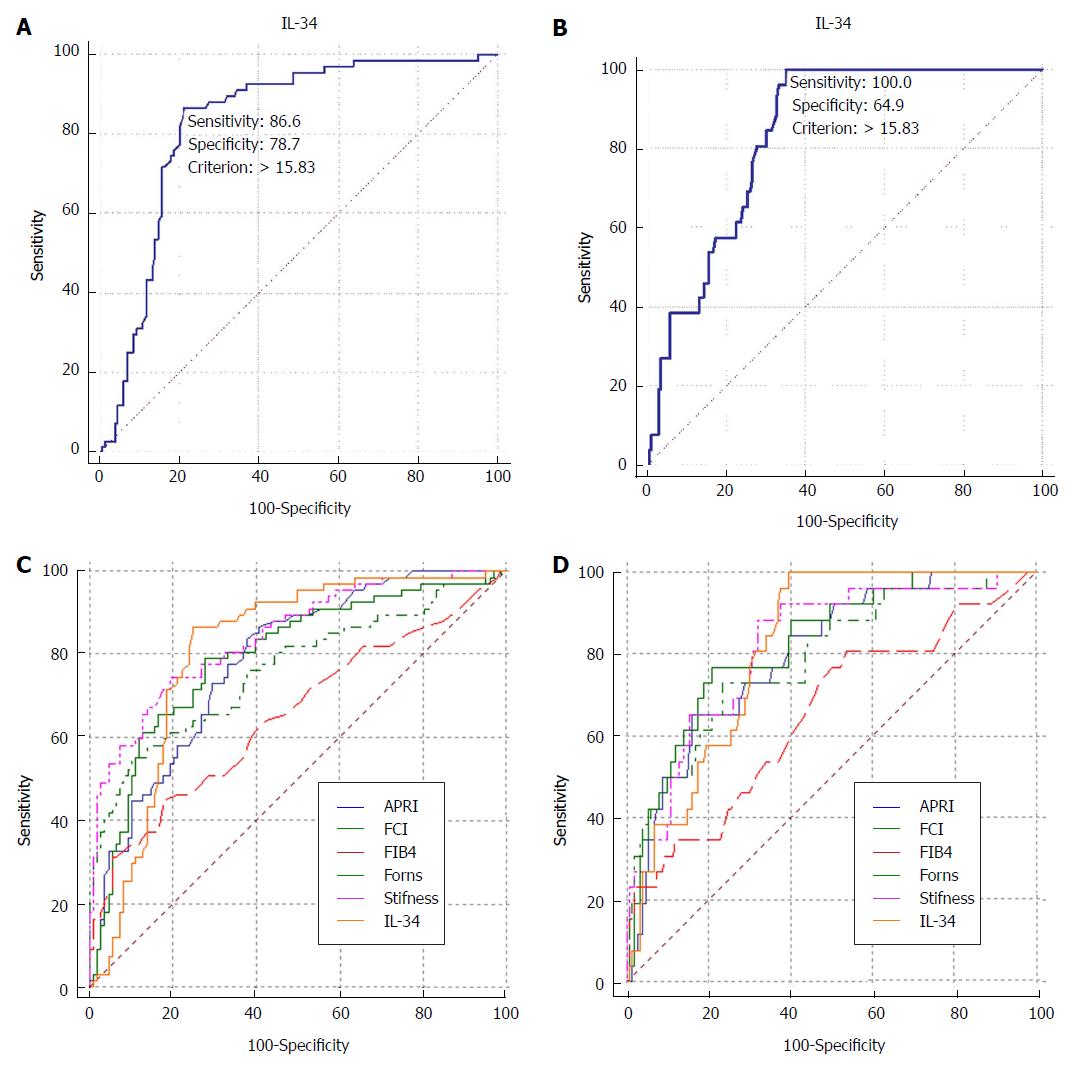

We aimed to determine whether severe liver fibrosis, defined as fibrosis at stages greater than or equal to S3 (S3-S4), in chronic HBV patients is critical for guiding the prognosis and treatment of patients with hepatitis B. Encouraged by our results showing that IL-34 may be a marker of fibrosis stage, we sought to determine whether IL-34 is a marker of severe liver fibrosis (S3-S4) and early cirrhosis (S4). ROC curve analysis resulted in AUCs of 0.829 and 0.836 for severe fibrosis (S3-S4) (Figure 3A) and early cirrhosis (S4) (Figure 3B), respectively. IL-34 levels predicted severe fibrosis (S3-S4) with a sensitivity of 86.6% and a specificity of 78.7%. When IL-34 level > 15.83 pg/mL was used as a cut-off to diagnose severe fibrosis. The sensitivity and specificity of IL-34 on predicting early cirrhosis (S4) are 100% and 64.9%, and the cut-off value is 15.83 pg/mL.

Different fibrosis scores (FIB-4, APRI, Forns and fibrosis-cirrhosis index) have been used to diagnose liver fibrosis or cirrhosis. We compared the performance of IL-34 to the performance of these serum fibrosis scores for the detection of severe liver fibrosis. We conducted a comparative ROC analysis for these scores for individually diagnosing severe liver fibrosis. There were significant differences in AUCs between IL-34 and the FIB-4 score (P = 0.005) in predicting severe fibrosis, indicating that IL-34 was superior to the FIB-4 score. IL-34 was also better than the FIB-4 score in diagnosing early cirrhosis (P = 0.0092). However, for both severe fibrosis and early cirrhosis, the diagnostic accuracy of IL-34 was similar to that of liver stiffness and other scores (Figure 3C and D, Table 2).

| AUC (95%CI) | |||

| S0 vs S1-S4 | S3-S4 vs S0-S2 | S4 vs S0-S3 | |

| IL-34 | 0.753 (0.659-0.848) | 0.809 (0.743-0.875) | 0.815 (0.747-0.883) |

| APRI | 0.714 (0.580-0.847) | 0.783 (0.715-0.850) | 0.797 (0.710-0.884) |

| FIB-4 | 0.577 (0.427-0.727) | 0.651 (0.564-0.738) | 0.651 (0.529-0.773) |

| Forns | 0.529 (0.405-0.653) | 0.762 (0.685-0.839) | 0.788 (0.689-0.886) |

| FCI | 0.580 (0.422-0.738) | 0.793 (0.723-0.863) | 0.822 (0.739-0.906) |

| Liver stiffness | 0.684 (0.565-0.803) | 0.844 (0.784-0.903) | 0.815 (0.728-0.902) |

The correct staging of liver fibrosis is important for guiding the clinical treatment of chronic hepatitis. Liver biopsy, the gold standard for staging liver fibrosis, is invasive and has many limitations[13]. Other recognized noninvasive methods for determining the stage of liver fibrosis also have many disadvantages[16]. Therefore, an increasing number of scholars are investigating noninvasive methods for staging liver fibrosis. In this study, we found that serum IL-34 levels are elevated in HBV-infected patients with severe liver fibrosis (S3-S4) and that IL-34 may be potential marker for differentiating early-stage fibrosis (S0-S2) from late-stage fibrosis (S3-S4) in patients with HBV-related liver fibrosis in China.

This study also clearly demonstrates the diagnostic value of IL-34 as a noninvasive biomarker in the assessment of HBV-related liver fibrosis in patients in China. We were able to demonstrate IL-34 as predictor of severe liver fibrosis (S3-S4) and early cirrhosis (S4) in HBV-infected patients in China. The AUC of IL-34 was 0.829 for the detection of severe liver fibrosis (S3-S4) and 0.836 for the detection of early cirrhosis (S4). Especially for early cirrhosis (S4) patients, the sensitivity can be up to 100%. This means that it may be possible to avoid missed diagnosis of early cirrhosis. After all, the effective treatments are available to reverse the progress of disease[17]. And, regardless of the situation of ALT and HBeAg, as long as there is an objective basis for cirrhosis, active antiviral therapy is recommended[10].

Compared with other serological models, IL-34 was comparable to the FIB-4 score for the detection of severe liver fibrosis (S3-S4) and early cirrhosis (S4). Even for diagnosing S0 liver fibrosis, IL-34 was comparable to the FIB-4 score (data not shown). Most scholars consider transient elastography to be a promising noninvasive method for the detection of fibrosis in chronic HBV patients[18]. However, this technique is usually only available in specialized centers. Another limitation of transient elastography is that it has a failure rate of approximately 20%, especially in the case of obese individuals[14]. Although the AUC of IL-34 was not significantly different from that of liver stiffness or other fibrosis scores except for FIB-4, IL-34 may be used as a biomarker, as it is sufficient by itself and can be detected in simple-to-obtain samples compared with other established complex fibrosis scores. Perhaps we can also try to combine it with other indicators to improve the effectiveness of disease diagnosis?

Because of the different phases of chronic HBV infection, ranging from stable disease with minimal injury in inactive carriers to rapid cirrhosis development in patients with highly active HBV infection[10], investigations on the mechanisms of liver inflammation and fibrosis together with the establishment of reliable markers for different HBV phases are very meaningful. We showed that serum levels of IL-34, reflective of profibrogenic macrophage activation[3], differ with the phases of HBV infection and are correlated with hepatic inflammation and liver fibrosis.

One of features of hepatotoxic immune responses with increased inflammation and fibrosis in chronic viral hepatitis is the induction of profibrogenic macrophages[3,4]. In accordance with the important role of liver macrophages in HBV-mediated liver damage, we observed high IL-34 levels in patients with HBeAg-positive or HBeAg-negative hepatitis. Patients with HBeAg-positive or HBeAg-negative hepatitis have a high risk of disease progression and development of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma due to increased hepatic inflammation and fibrogenesis[10,19-21]. In contrast, IL-34 levels in inactive HBV carriers with HBV DNA levels ≤ 2000 U/mL and normal transaminase levels did not differ from those in healthy subjects, indicating that the low levels of activation of the innate immune system reflect good prognosis[10,19].

Although the IL-34 levels of immune-tolerant patients were markedly different from those of HBeAg-positive or HBeAg-negative hepatitis patients, immune-tolerant patients had comparable IL-34 levels to healthy subjects. This might indicate that if the human immune system fails to respond to HBV, the damage to the liver by the virus is minimal[22]. Liver biopsies in immune-tolerant patients generally show no signs of significant inflammation or fibrosis[23,24]. Given that serum IL-34 concentrations were strongly correlated with aminotransferase levels and could differentiate patients with extensive hepatic inflammation from subjects with reduced inflammatory activity, IL-34 may be used as a potential biomarker for hepatic inflammation.

In summary, IL-34 may aid in the staging of liver fibrosis and diagnosing different phases of HBV infection in China. These processes are critical for guiding the treatment of chronic HBV infection. IL-34 is known to regulate the profibrogenic functions of macrophages by binding to its receptor[3,6,7]. IL-34 and its receptor are highly expressed in hepatocytes in patients with liver fibrosis, mainly in hepatocytes located around fibrotic and inflammatory lesions[3,25]. We hypothesized that by preventing IL-34 from binding with its receptor, the progression of liver fibrosis can be delayed, and inflammation and necrosis of the liver can be prevented. Thus, apart from its above-mentioned function in diagnosis, IL-34 may also be investigated as a therapeutic target for reversing fibrosis.

It is generally believed that the persistence of inflammation plays an important role in the progression of liver fibrosis. Previous studies have shown that interleukin (IL)-34 is an inflammatory cytokine involved in the induction of activation of profibrogenic macrophages, which is associated with the severity of liver fibrosis and inflammation in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

in order to be helpful to demonstrate the mechanism of liver fibrosis from the perspective of inflammation and provide a new direction for the search of potential new serological diagnostic fibrosis indicators, we investigated the relationship between IL-34 and liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.

This study aimed to investigate whether serum IL-34 levels are correlated with hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in patients with chronic HBV infection.

In this study, serum IL-34 levels of 19 healthy controls and 175 patients with chronic HBV infection undergoing biopsy were analyzed.

We found that the serum IL-34 levels were different among phases of chronic HBV infection and stages of inflammation and fibrosis. We also thought that the serum IL-34 level has potential to diagnose liver fibrosis through comparative analysis of the diagnostic value of IL-34 and other diagnostic methods, except for pathological diagnosis.

Serum IL-34 level has the potential to be a new indicator of liver inflammation and fibrosis in patients with chronic HBV infection.

The diagnostic accuracy of serum IL-34 level is not ideal at present. Thus, we can try combining IL-34 with any of other scores and/or with any clinical variable in order to obtain a new "score" with enhanced diagnostic accuracy. Another approach is to increase the sample size for testing.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Vespasiani-Gentilucci U S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Pellicoro A, Ramachandran P, Iredale JP, Fallowfield JA. Liver fibrosis and repair: immune regulation of wound healing in a solid organ. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:181-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 777] [Cited by in RCA: 1002] [Article Influence: 91.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liao B, Wang Z, Lin S, Xu Y, Yi J, Xu M, Huang Z, Zhou Y, Zhang F, Hou J. Significant fibrosis is not rare in Chinese chronic hepatitis B patients with persistent normal ALT. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Preisser L, Miot C, Le Guillou-Guillemette H, Beaumont E, Foucher ED, Garo E, Blanchard S, Frémaux I, Croué A, Fouchard I. IL-34 and macrophage colony-stimulating factor are overexpressed in hepatitis C virus fibrosis and induce profibrotic macrophages that promote collagen synthesis by hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2014;60:1879-1890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tacke F. Functional role of intrahepatic monocyte subsets for the progression of liver inflammation and liver fibrosis in vivo. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2012;5:S27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Koyama Y, Brenner DA. Liver inflammation and fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:55-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 548] [Cited by in RCA: 903] [Article Influence: 112.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hume DA, MacDonald KP. Therapeutic applications of macrophage colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) and antagonists of CSF-1 receptor (CSF-1R) signaling. Blood. 2012;119:1810-1820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 433] [Cited by in RCA: 562] [Article Influence: 40.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nakamichi Y, Udagawa N, Takahashi N. IL-34 and CSF-1: similarities and differences. J Bone Miner Metab. 2013;31:486-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ma X, Lin WY, Chen Y, Stawicki S, Mukhyala K, Wu Y, Martin F, Bazan JF, Starovasnik MA. Structural basis for the dual recognition of helical cytokines IL-34 and CSF-1 by CSF-1R. Structure. 2012;20:676-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shoji H, Yoshio S, Mano Y, Kumagai E, Sugiyama M, Korenaga M, Arai T, Itokawa N, Atsukawa M, Aikata H. Interleukin-34 as a fibroblast-derived marker of liver fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | European Association for the Study of the Liver; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67:370-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3745] [Cited by in RCA: 3774] [Article Influence: 471.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Afdhal NH. Biopsy or biomarkers: is there a gold standard for diagnosis of liver fibrosis? Clin Chem. 2004;50:1299-1300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Beinhardt S, Staettermayer AF, Rutter K, Maresch J, Scherzer TM, Steindl-Munda P, Hofer H, Ferenci P. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 patients at an academic center in Europe involved in prospective, controlled trials: is there a selection bias? Hepatology. 2012;55:30-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sharma S, Khalili K, Nguyen GC. Non-invasive diagnosis of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16820-16830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Castera L. Noninvasive methods to assess liver disease in patients with hepatitis B or C. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1293-1302.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 451] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Degos F, Perez P, Roche B, Mahmoudi A, Asselineau J, Voitot H, Bedossa P; FIBROSTIC study group. Diagnostic accuracy of FibroScan and comparison to liver fibrosis biomarkers in chronic viral hepatitis: a multicenter prospective study (the FIBROSTIC study). J Hepatol. 2010;53:1013-1021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Motola DL, Caravan P, Chung RT, Fuchs BC. Noninvasive Biomarkers of Liver Fibrosis: Clinical Applications and Future Directions. Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2014;2:245-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, Schiff E, Han KH, Lai CL, Safadi R, Lee SS, Halota W, Goodman Z. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;52:886-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in RCA: 772] [Article Influence: 51.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chon YE, Choi EH, Song KJ, Park JY, Kim DY, Han KH, Chon CY, Ahn SH, Kim SU. Performance of transient elastography for the staging of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fattovich G, Bortolotti F, Donato F. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B: special emphasis on disease progression and prognostic factors. J Hepatol. 2008;48:335-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 909] [Cited by in RCA: 964] [Article Influence: 56.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Villeneuve JP. The natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Clin Virol. 2005;34 Suppl 1:S139-S142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fattovich G, Boscaro S, Noventa F, Pornaro E, Stenico D, Alberti A, Ruol A, Realdi G. Influence of hepatitis delta virus infection on progression to cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis type B. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:931-935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hui CK, Leung N, Yuen ST, Zhang HY, Leung KW, Lu L, Cheung SK, Wong WM, Lau GK; Hong Kong Liver Fibrosis Study Group. Natural history and disease progression in Chinese chronic hepatitis B patients in immune-tolerant phase. Hepatology. 2007;46:395-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mani H, Kleiner DE. Liver biopsy findings in chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009;49:S61-S71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shao J, Wei L, Wang H, Sun Y, Zhang LF, Li J, Dong JQ. Relationship between hepatitis B virus DNA levels and liver histology in patients with chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2104-2107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jia JB, Wang WQ, Sun HC, Zhu XD, Liu L, Zhuang PY, Zhang JB, Zhang W, Xu HX, Kong LQ. High expression of macrophage colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor in peritumoral liver tissue is associated with poor outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Oncologist. 2010;15:732-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |