Published online Jan 7, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i1.58

Peer-review started: October 27, 2017

First decision: November 21, 2017

Revised: December 2, 2017

Accepted: December 12, 2017

Article in press: December 12, 2017

Published online: January 7, 2018

Processing time: 72 Days and 18.6 Hours

To investigate the association between smoking habits and surgical outcomes in hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (B-HCC) and hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related HCC (C-HCC) and clarify the clinicopathological features associated with smoking status in B-HCC and C-HCC patients.

We retrospectively examined the cases of the 341 consecutive patients with viral-associated HCC (C-HCC, n = 273; B-HCC, n = 68) who underwent curative surgery for their primary lesion. We categorized smoking status at the time of surgery into never, ex- and current smoker. We analyzed the B-HCC and C-HCC groups’ clinicopathological features and surgical outcomes, i.e., disease-free survival (DFS), overall survival (OS), and disease-specific survival (DSS). Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using a Cox proportional hazards regression model. We also performed subset analyses in both patient groups comparing the current smokers to the other patients.

The multivariate analysis in the C-HCC group revealed that current-smoker status was significantly correlated with both OS (P = 0.0039) and DSS (P = 0.0416). In the B-HCC patients, no significant correlation was observed between current-smoker status and DFS, OS, or DSS in the univariate or multivariate analyses. The subset analyses comparing the current smokers to the other patients in both the C-HCC and B-HCC groups revealed that the current smokers developed HCC at significantly younger ages than the other patients irrespective of viral infection status.

A smoking habit is significantly correlated with the overall and disease-specific survivals of patients with C-HCC. In contrast, the B-HCC patients showed a weak association between smoking status and surgical outcomes.

Core tip: We retrospectively analyzed the association between smoking habits and surgical outcomes in 68 cases of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (B-HCC) and 273 cases of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related HCC (C-HCC). Smoking habit was revealed as significantly correlated with the overall survival and disease-specific survival of the C-HCC patients, whereas the B-HCC patient group showed a weak association between smoking habit and surgical outcomes. Our subset analyses comparing the current smokers to the other patients revealed that the current smokers developed HCC at significantly younger ages compared to the other patients irrespective of viral infection status.

- Citation: Kai K, Komukai S, Koga H, Yamaji K, Ide T, Kawaguchi A, Aishima S, Noshiro H. Correlation between smoking habit and surgical outcomes on viral-associated hepatocellular carcinomas. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(1): 58-68

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i1/58.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i1.58

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), is the fifth most common cancer in the world and the second most common cause of cancer deaths, accounting for about 745000 deaths per year globally[1]. Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections represent the leading cause of HCC (60%-70%), with a total incidence of 16/100000 globally[2]. The prevalence of HBV and HCV infections varies among geographic regions. In Japan, HCV-related HCC (C-HCC) is the most common HCC infection, accounting for approx. 70% of all HCC cases[3].

It is reported that the natural histories of C-HCC and HBV-related HCC (B-HCC) differ: HCV infection leads to the development of HCC mainly through indirect pathways (such as chronic inflammation, cell deaths and proliferation) whereas HBV causes HCC through direct and indirect pathways as it can integrate into the host genome, affecting cellular signaling and growth control[4]. HCC is thus typically found in HCV patients with cirrhosis, although it is sometimes found in HBV patients without significant liver cirrhosis.

Curative surgical resection is the most frequent therapeutic strategy for HCC. The influence of the patients’ viral infection status on surgical outcomes has been well investigated. A meta-analysis in 2011 reported that non-B non-C (NBNC)-HCC patients showed significantly better disease-free survival (DFS) surgical outcomes; in addition, although the result was not statistically significant, the overall survival (OS) of NBNC-HCC patients was more favorable compared to that of both B-HCC and C-HCC patients[5]. This meta-analysis of 20 studies also reported that the OS and the DFS were not significantly different between B-HCC and C-HCC groups[5]. A Japanese nationwide study of nearly 12000 patients also reported that both the OS and DFS after surgical resection were not significantly different between the C-HCC and B-HCC groups, although the liver function in the C-HCC group was significantly worse than that in the B-HCC group[6].

Generally, lifestyle-associated factors such as metabolic disease, alcohol consumption, and smoking status have tended to be left out of investigations when discussing factors affecting the pathogenesis or surgical outcomes of viral-associated HCC. It is well known that lifestyle factors are significantly involved in the carcinogenesis of NBNC-HCC and it has been reported that metabolic factors correlate also with prognosis of NBNC-HCC[7]. Although epidemiological studies obtained evidence that smoking habit is involved in HCC carcinogenesis[8-10], little attention has been paid to the relationship between smoking habit and surgical outcomes of HCC.

We recently analyzed the relationship between smoking status and surgical outcomes in patients with NBNC-HCC, and our analysis revealed that smoking habits are significantly correlated with the curatively resected surgical outcomes of NBNC-HCC[11]. We then speculated that if smoking habits truly affect the postoperative prognosis of NBNC-HCC by one or more unknown mechanisms, smoking habits might also affect the postoperative prognosis of viral-associated HCC patients. In addition, since the natural histories of NBNC-HCC, B-HCC, and C-HCC differ, the clinicopathologic characteristics associated with smoking status might be different per viral infection status.

We thus conducted the present study to (1) investigate the association between smoking habits and surgical outcomes in B-HCC and C-HCC patients who underwent curative surgery; and (2) clarify the clinicopathological features associated with smoking habits in patients with B-HCC or C-HCC.

This retrospective study’s protocol was reviewed by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at Saga University and approved (approval No. 28-23). The written informed consent for the use of their clinical information was obtained from all of the study’s patients. From 1984 to 2012, consecutive 477 cases of curative surgery for primary HCC at Saga University Hospital (in the city of Saga, which is located on the island of Kyushu, the southwestern-most of Japan’s main islands) were initially enrolled the study. Definition of the HBV infection and HCV infection was HBsAg-positive and HCVAb-positive in serological tests, respectively. We excluded the following patients: those with NBNC-HCC (serologically both HBsAg- and HCVAb-negative) cases (n = 83) and those with co-infection of HBV with HCV (n = 9). Among the remaining 385 cases of C-HCC or B-HCC, we included only the cases for which all of the following information was available: the patient’s age, gender, body mass index (BMI), diabetes mellitus status, smoking status (as defined below), alcohol abuse status, tumor size, status of portal vein invasion (Vp), number of primary tumors (solitary or multiple), T factor of the TMN classification, indocyanine green retention rate at 15 minutes (ICG R15), and serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level. The final patient series was comprised of the 341 patients with viral-associated HCC (C-HCC, n = 273; B-HCC, n = 68).

We obtained the information about smoking status and alcohol abuse status from the patients’ medical records. This information had been self-reported by the patients in an interview by medical staff. Each patient’s smoking status at the time of surgery was categorized into never smoker, ex-smoker, and current smoker based on the definitions in our recent study[11], as follows. ‘Never smoker’ is self-explanatory. ‘Ex-smoker’ was defined as having quit smoking completely ≥ 1 year before the patient’s surgery. Definition of ‘Current smoker’ was an individual who continued to smoke within 1 year prior to the surgery.

We have defined alcohol abuse as a daily ethanol intake > 40 g for men and > 20 g for women.

Statistical analyses were performed by the authors Komukai S and Kawaguchi A, who are statisticians. The software JMP ver. 12.2 and SAS ver. 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC, United States) were used for the statistical analyses. They compared pairs of groups by Fisher’s exact test, the χ2 test and Student’s t-test, as appropriate. The patients’ DFS, OS and disease-specific survival (DSS) were determined as described[11]. A univariate analysis and a multivariate analysis were performed using a Cox proportional hazards regression model.

The multivariate analysis was conducted in order to adjust the potential covariates in the comparison of smoking status groups; the patients’ age and gender were always kept in the model, and other parameters were identified by the stepwise procedure using the P value threshold of 0.2. The complete patient series’ median age (67 years old) was used as the age cut-off. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for calculating each of the postoperative survival curves. The log-rank test was used to compare the differences in survival curves. P value < 0.05 were accepted as significant.

The clinicopathological features of 273 cases of C-HCC and 68 cases of B-HCC are summarized in Table 1. The B-HCC group developed HCC at significantly younger ages (mean 57.15 years old) compared to the C-HCC group (mean: 67.16 years, P < 0.0001). Both the C- and B-HCC groups showed a male predominance, and the B-HCC patients showed a higher male predominance rate (86.76%) compared to the C-HCC patients (74.36%, P = 0.03).

| HCV (n = 273) | HBV (n = 68) | P value | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 67.16 ± 8.56 | 57.15 ± 12.47 | < 0.0001 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 203 (74.36) | 59 (86.76) | 0.0300 |

| Female | 70 (25.64) | 9 (13.24) | |

| Smoking habit | |||

| Never | 111 (40.66) | 21 (30.88) | 0.0715 |

| Ex | 74 (27.11) | 15 (22.06) | |

| Current | 88 (32.23) | 32 (47.06) | |

| Alcohol abuse | |||

| (+) | 63 (23.08) | 22 (32.35) | 0.1136 |

| (-) | 210 (76.92) | 46 (67.65) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||

| (+) | 62 (22.71) | 12 (17.65) | 0.3647 |

| (-) | 211 (77.29) | 56 (82.35) | |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 22.49 ± 3.29 | 22.93 ± 3.80 | 0.3478 |

| ICG R15 (%) (mean ± SD) | 18.63 ± 9.03 | 13.31 ± 6.30 | < 0.0001 |

| AFP (ng/mL), Median (range) | 26.2 (0, 29800) | 31 (1, 271600) | 0.0625 |

| Tumor size (mean ± SD mm) | 37.37 ± 25.62 | 49.72 ± 33.14 | 0.0052 |

| Solitary/Multiple | |||

| Solitary | 182 (66.67) | 41 (60.29) | 0.3230 |

| Multiple | 91 (33.33) | 27 (39.71) | |

| Vp | |||

| (+) | 74 (27.11) | 29 (42.65) | 0.0125 |

| (-) | 199 (72.89) | 39 (57.35) | |

| T factor | |||

| T1/2 | 156 (57.14) | 32 (47.06) | 0.1347 |

| T3/4 | 117 (42.86) | 36 (52.94) |

Regarding smoking status, no significant difference was observed between the two groups although the B-HCC group tended to have more current smokers (47.06%) compared to the C-HCC group (32.23%). The status of alcohol abuse, diabetes mellitus, and BMI did not differ between the C- and B-HCC patients.

The percentage of ICG R15 was significantly higher in the C-HCC group compared to the B-HCC group (P < 0.0001), indicating that the patients with HCV infection developed HCC at a more advanced stage of chronic hepatitis compared to the patients with HBV infection. The serum AFP level of at the time of surgery tended to be higher in the B-HCC patients compared to the C-HCC patients, but the difference was not significant. The tumor sizes in the B-HCC group were significantly larger than those of the C-HCC group (mean tumor sizes 49.72 mm vs 37.37 mm, P = 0.0052), and the percentage of Vp was significantly higher in the B-HCC group compared to the C-HCC (42.65% vs 27.11%, P = 0.0125). There was no significant difference regarding T factor or multiple occurrence between the B-and C-HCC groups.

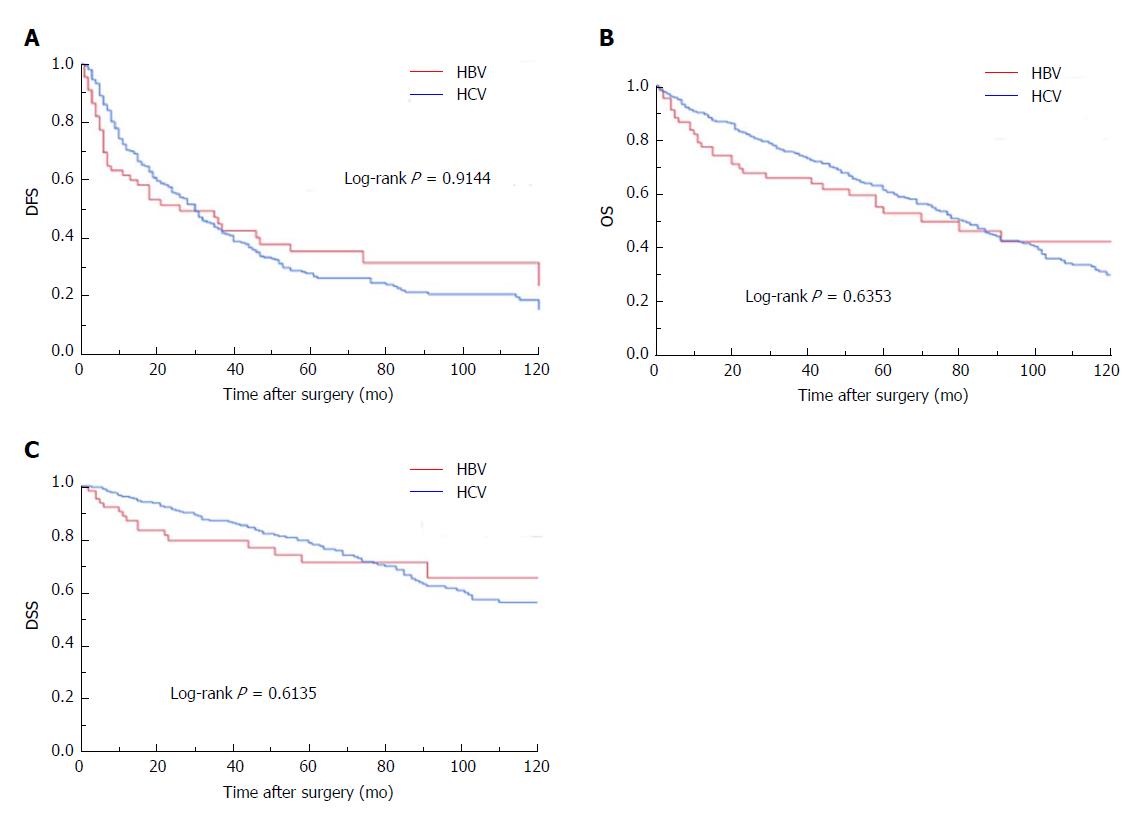

We compared the surgical outcomes (DFS, OS, DSS) of the B-HCC and C-HCC groups and found no significant difference between the groups in DFS, OS or DSS (Figure 1).

The results of the univariate analyses for surgical outcomes in the C-HCC patient group are summarized in Table 2. The factors that were significantly correlated with the DFS of the C-HCC patient group were alcohol abuse (P = 0.0321), BMI (P = 0.0270), ICG R15 (P = 0.0088), tumor size (P = 0.0305), multiple tumors (P = 0.0021), and T factor (P < 0.0001). Smoking status was not correlated with the DFS of the C-HCC patients.

| DFS | OS | DSS | |||||

| Characteristics | n | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| Age | 0.9234 | 0.5143 | 0.7101 | ||||

| ≤ 67 | 133 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > 67 | 140 | 1.01381 (0.7665, 1.3409) | 1.10679 (0.8159, 1.5015) | 0.92155 (0.599, 1.4177) | |||

| Gender | 0.5699 | 0.5110 | 0.2434 | ||||

| Female | 70 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Male | 203 | 0.91269 (0.666, 1.2508) | 1.12916 (0.786, 1.6221) | 1.38366 (0.8019, 2.3876) | |||

| Smoking habit (Ex + current) | 0.5978 | 0.1262 | 0.2147 | ||||

| Absent | 111 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Present | 162 | 0.92696 (0.6994, 1.2286) | 1.27849 (0.9332, 1.7516) | 1.32797 (0.8483, 2.0788) | |||

| Smoking habit (current) | 0.8864 | 0.0144 | 0.0483 | ||||

| Absent | 185 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Present | 88 | 1.02258 (0.7527, 1.3892) | 1.47783 (1.0808, 2.0207) | 1.55795 (1.0033, 2.4192) | |||

| Alcohol abuse | 0.0321 | 0.8232 | 0.7027 | ||||

| Absent | 210 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Present | 63 | 0.68132 (0.4797, 0.9678) | 0.95952 (0.6677, 1.3788) | 0.90325 (0.5356, 1.5232) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.3149 | 0.5259 | 0.9487 | ||||

| Absent | 211 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Present | 62 | 1.18657 (0.85, 1.6564) | 1.12207 (0.7861, 1.6017) | 0.98302 (0.5831, 1.6572) | |||

| BMI | 0.0270 | 0.2082 | 0.6409 | ||||

| ≤ Median | 137 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > Median | 136 | 0.72863 (0.5503, 0.9647) | 0.82193 (0.6056, 1.1155) | 0.9026 (0.5868, 1.3884) | |||

| ICG R15 (%) | 0.0088 | 0.2391 | 0.6896 | ||||

| ≤ Median | 111 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > Median | 162 | 1.47199 (1.1021, 1.9659) | 1.20672 (0.8825, 1.65) | 1.09334 (0.7056, 1.6941) | |||

| AFP | 0.2274 | 0.0402 | 0.1371 | ||||

| ≤ Median | 136 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > Median | 137 | 1.18795 (0.8981, 1.5713) | 1.37689 (1.0144, 1.8689) | 1.38776 (0.901, 2.1376) | |||

| Tumor size | 0.0305 | 0.0019 | 0.0070 | ||||

| ≤ Median | 161 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > Median | 112 | 1.37235 (1.0303, 1.828) | 1.63014 (1.1982, 2.2178) | 1.81608 (1.1773, 2.8016) | |||

| Solitary/Multiple | 0.0021 | 0.0001 | 0.1182 | ||||

| Solitary | 182 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Multiple | 91 | 1.59365 (1.1835, 2.1459) | 1.8536 (1.3563, 2.5332) | 1.43932 (0.9115, 2.2728) | |||

| Vp | 0.0767 | 0.0004 | 0.0177 | ||||

| Absent | 199 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Present | 74 | 1.33528 (0.9695, 1.839) | 1.81728 (1.3073, 2.5262) | 1.76737 (1.104, 2.8294) | |||

| T12/T34 | < 0.0001 | 0.0008 | 0.0315 | ||||

| T12 | 156 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| T34 | 117 | 1.81021 (1.3644, 2.4017) | 1.68381 (1.2412, 2.2843) | 1.60589 (1.0429, 2.4728) | |||

The factors that were revealed to be significantly correlated with the OS of the C-HCC patient group were smoking (current vs other; P = 0.0144), serum AFP level (P = 0.0402), tumor size (P = 0.0019), multiple tumors (P = 0.0001), Vp (P = 0.0004), and T factor (P = 0.0008).

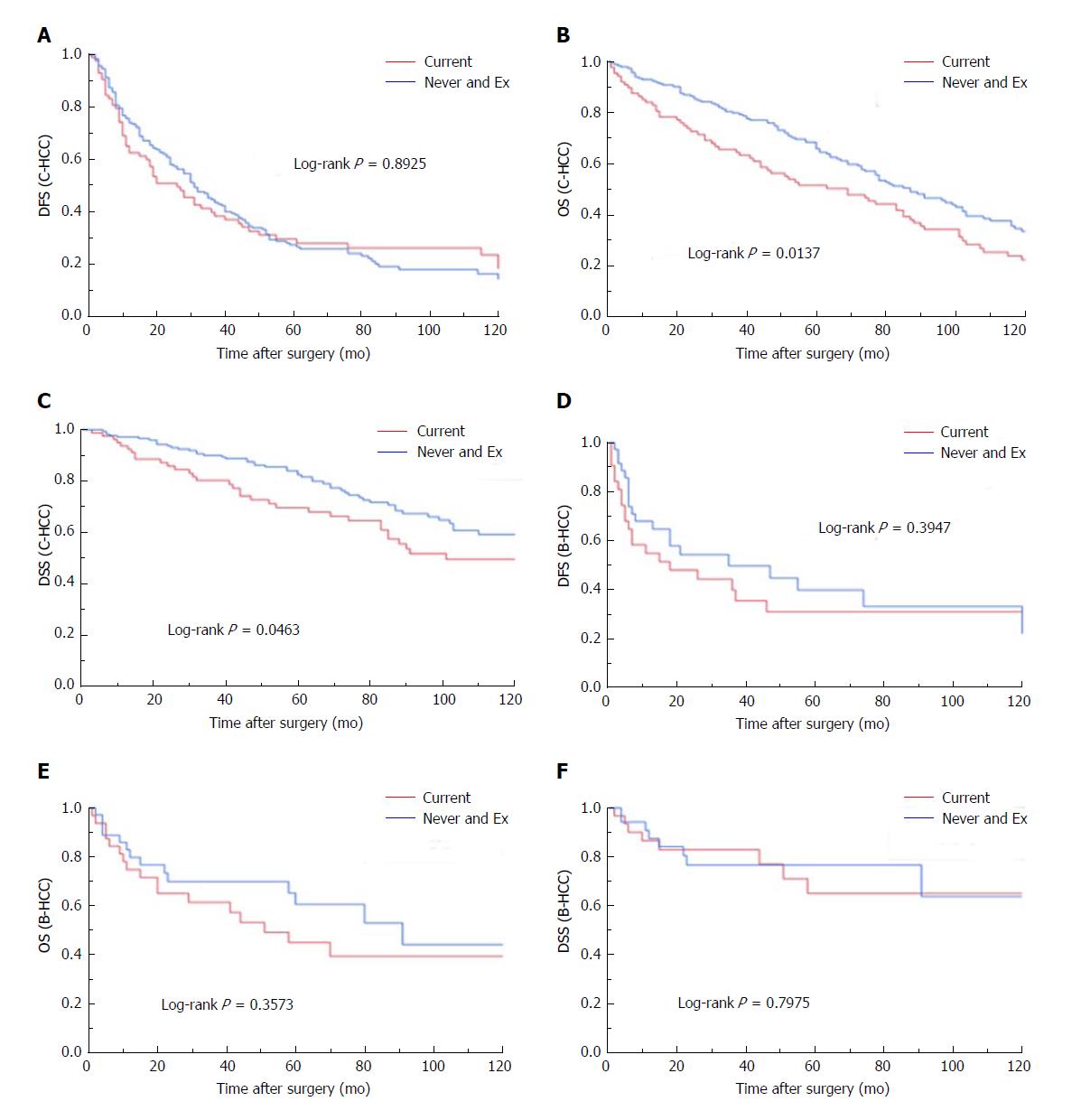

The factors found to be significantly correlated with disease-specific survival were smoking (current vs other; P = 0.0483), tumor size (P = 0.0070), Vp (P = 0.0177), and T factor (P = 0.0315). The survival curves per smoking habit are demonstrated in Figure 2A-C. The current-smoking group showed significantly poor survival curves compared to the never + Ex patient group for both OS and DSS. However, no significant difference was observed in DFS between the current-smoking group and never + Ex patient group.

The results of the multivariate analyses for DFS, OS and DSS are summarized in Table 3. Current-smoker status showed no correlation with DFS (P = 0.2364). The factors that were significantly correlated with DFS were alcohol abuse (P = 0.0025), BMI (P = 0.0165), ICG R15 (P = 0.0027) and T factor (P < 0.0001). In the multivariate analysis for OS, current-smoker status was significantly correlated with OS (P = 0.0039). The only other factor that was significantly correlated with OS was T factor (P = 0.0005). The factors significantly correlated with DSS were current-smoker status and T factor (P = 0.0416 and P = 0.0226, respectively).

| Type | Characteristics | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| DFS | Smoking habit (current) | 1.22892 (0.8736, 1.7287) | 0.2364 |

| Age (67 < yr) | 0.98815 (0.7442, 1.3121) | 0.9343 | |

| Gender (male) | 0.9536 (0.6797, 1.338) | 0.7833 | |

| Alcohol abuse | 0.55622 (0.3803, 0.8135) | 0.0025 | |

| BMI (median <) | 0.70403 (0.5284, 0.9381) | 0.0165 | |

| ICG R15 (median <) | 1.59531 (1.1763, 2.1635) | 0.0027 | |

| T factor (T3/4) | 1.90638 (1.4279, 2.5452) | < 0.0001 | |

| OS | Smoking habit (current) | 1.69259 (1.1844, 2.4187) | 0.0039 |

| Age (67 < yr) | 1.18434 (0.8668, 1.6182) | 0.2880 | |

| Gender (male) | 1.01654 (0.687, 1.504) | 0.9346 | |

| Alcohol abuse | 0.74612 (0.5061, 1.1) | 0.1392 | |

| BMI (median <) | 0.89005 (0.6489, 1.2208) | 0.4701 | |

| ICG R15 (median <) | 1.32015 (0.9524, 1.83) | 0.0955 | |

| T factor (T3/4) | 1.74555 (1.2767, 2.3865) | 0.0005 | |

| DSS | Smoking habit (current) | 1.68394 (1.0201, 2.7798) | 0.0416 |

| Age (67 < yr) | 1.00555 (0.6464, 1.5644) | 0.9804 | |

| Gender (male) | 1.25081 (0.6981, 2.2412) | 0.4520 | |

| Alcohol abuse | 0.66203 (0.3796, 1.1547) | 0.1462 | |

| BMI (median <) | 0.97081 (0.6206, 1.5185) | 0.8967 | |

| ICG R15 (median <) | 1.18278 (0.7484, 1.8692) | 0.4722 | |

| T factor (T3/4) | 1.67615 (1.0752, 2.613) | 0.0226 |

The results of the univariate analyses for surgical outcomes in the B-HCC group are summarized in Table 4. The factors that were significantly correlated with the DFS of the B-HCC patient group were alcohol abuse (P = 0.0183), multiple tumors (P = 0.0002) and T factor (P = 0.0042). The factors significantly correlated with the OS of the B-HCC group were the serum AFP level (P = 0.0015), multiple tumors (P = 0.0001), Vp (P = 0.0035), and T factor (P = 0.0001). The factors revealed to be significantly correlated with disease-specific survival were the serum AFP level (P = 0.0114), multiple tumors (P = 0.0013), Vp (P = 0.0362), and T factor (P = 0.0019).

| DFS | OS | DSS | |||||

| Characteristics | n | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| Age | 0.9417 | 0.8991 | 0.3769 | ||||

| ≤ 67 | 54 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > 67 | 14 | 0.97131 (0.445, 2.1202) | 1.05615 (0.4541, 2.4565) | 0.5123 (0.1162, 2.2588) | |||

| Gender | 0.6063 | 0.1844 | 0.3363 | ||||

| Female | 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Male | 59 | 1.28118 (0.4993, 3.2876) | 2.64152 (0.6294, 11.0865) | 2.70202 (0.3562, 20.4981) | |||

| Smoking habit (Ex + current) | 0.8323 | 0.5660 | 0.9544 | ||||

| Absent | 21 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Present | 47 | 0.93056 (0.478, 1.8115) | 1.26612 (0.5656, 2.8343) | 0.96953 (0.336, 2.7975) | |||

| Smoking habit (current) | 0.4008 | 0.3620 | 0.8001 | ||||

| Absent | 36 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Present | 32 | 1.30547 (0.7009, 2.4314) | 1.38988 (0.6848, 2.8209) | 1.13501 (0.4258, 3.0251) | |||

| Alcohol abuse | 0.0183 | 0.0706 | 0.5674 | ||||

| Absent | 46 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Present | 22 | 0.4139 (0.199, 0.861) | 0.45823 (0.1966, 1.0679) | 0.73339 (0.2534, 2.1228) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.4682 | 0.6700 | 0.8752 | ||||

| Absent | 56 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Present | 12 | 1.32065 (0.6229, 2.7999) | 1.21513 (0.4959, 2.9773) | 1.10618 (0.3141, 3.8962) | |||

| BMI | 0.3087 | 0.9126 | 0.6383 | ||||

| ≤ Median | 33 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > Median | 35 | 1.3863 (0.7392, 2.6) | 0.96125 (0.4746, 1.9468) | 1.26746 (0.4718, 3.4046) | |||

| ICG R15 (%) | 0.6240 | 0.8562 | 0.5468 | ||||

| ≤ Median | 49 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > Median | 19 | 0.83516 (0.4064, 1.7163) | 1.07744 (0.4808, 2.4147) | 1.38526 (0.4799, 3.9983) | |||

| AFP | 0.0665 | 0.0015 | 0.0114 | ||||

| ≤ Median | 34 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > Median | 34 | 1.80218 (0.9606, 3.3809) | 3.54578 (1.6235, 7.7443) | 4.36412 (1.3942, 13.6606) | |||

| Tumor size | 0.1252 | 0.2124 | 0.0585 | ||||

| ≤ Median | 28 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > Median | 40 | 1.67393 (0.8665, 3.2339) | 1.61822 (0.7594, 3.4483) | 3.37156 (0.9574, 11.8735) | |||

| Solitary/Multiple | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.0013 | ||||

| Solitary | 41 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Multiple | 27 | 3.30417 (1.7552, 6.2201) | 4.6829 (2.1913, 10.0073) | 6.42975 (2.0644, 20.0257) | |||

| Vp | 0.0598 | 0.0035 | 0.0362 | ||||

| Absent | 39 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Present | 29 | 1.85208 (0.975, 3.5182) | 2.94188 (1.4258, 6.07) | 2.92487 (1.0717, 7.9823) | |||

| T12/T34 | 0.0042 | 0.0001 | 0.0019 | ||||

| T12 | 32 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| T34 | 36 | 2.60213 (1.3531, 5.0043) | 5.55785 (2.3542, 13.1211) | 10.58522 (2.3795, 47.0876) | |||

The survival curves of DFS, OS and DSS per smoking status are demonstrated in Figure 2D-F. Smoking status was not correlated with the DFS, OS or DSS of the B-HCC patients.

The results of the multivariate analyses are summarized in Table 5. The two factors that were significantly correlated with the DFS of the B-HCC patients were alcohol abuse (P = 0.0119) and multiple tumors (P = 0.0004). The factors that were significantly correlated with the patients’ OS were alcohol abuse (P = 0.0312) and multiple tumors (P = 0.0001). The only factor that was significantly correlated with disease-specific survival was multiple tumors (P = 0.0009). Current-smoker status showed no correlation with any DFS, OS or DSS.

| Type | Characteristics | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| DFS | Smoking habit (current) | 1.41417 (0.7413, 2.698) | 0.2930 |

| Age (67 < yr) | 0.9339 (0.4189, 2.0818) | 0.8672 | |

| Gender (male) | 1.82154 (0.6845, 4.8477) | 0.2298 | |

| Alcohol abuse | 0.37957 (0.1785, 0.8072) | 0.0119 | |

| Multiple tumor | 3.18518 (1.6783, 6.045) | 0.0004 | |

| OS | Smoking habit (current) | 1.43613 (0.6865, 3.0045) | 0.3365 |

| Age (67 < yr) | 0.88873 (0.3727, 2.119) | 0.7902 | |

| Gender (male) | 3.66949 (0.8392, 16.0457) | 0.0842 | |

| Alcohol abuse | 0.38587 (0.1622, 0.9177) | 0.0312 | |

| Multiple tumor | 4.91853 (2.2445, 10.7785) | 0.0001 | |

| DSS | Smoking habit (current) | 0.98786 (0.3539, 2.7572) | 0.9814 |

| Age (67 < yr) | 0.37251 (0.0808, 1.7181) | 0.2055 | |

| Gender (male) | 3.89167 (0.4809, 31.4908) | 0.2027 | |

| Alcohol abuse | 0.98786 (0.3539, 2.7572) | 0.3991 | |

| Multiple tumor | 7.08829 (2.2387, 22.4436) | 0.0009 |

To clarify the clinicopathological characteristics of the current smokers in the C-HCC and B-HCC groups, we performed subset analyses regarding the clinicopathological factors per current-smoker status (Table 6).

| HCV (n = 273) | HBV (n = 68) | |||||

| Current (n = 88) | Never + Ex (n = 185) | P value | Current (n = 32) | Never + Ex (n = 36) | P value | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 65.34 ± 7.82 | 68.02 ± 8.77 | 0.0153 | 53.66 ± 13.74 | 60.25 ± 10.46 | 0.0284 |

| Gender (male/female) | 81/7 | 122/63 | < 0.0001 | 31/1 | 28/8 | 0.0204 |

| Alcohol abuse (+/-) | 35/53 | 28/157 | < 0.0001 | 13/19 | 9/27 | 0.1692 |

| Diabetes mellitus (+/-) | 20/68 | 42/143 | 0.9964 | 5/27 | 7/29 | 0.6801 |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 21.71 ± 2.74 | 22.87 ± 3.47 | 0.0031 | 23.01 ± 3.89 | 22.85 ± 3.77 | 0.8656 |

| ICG R15 (%) | 16.14 ± 7.24 | 19.81 ± 9.56 | 0.0005 | 12.54 ± 5.25 | 14.00 ± 7.11 | 0.3451 |

| AFP (ng/mL), median (range) | 20.5 (2, 29800) | 29 (0, 19500) | 0.4338 | 64.9 (1, 271600) | 14.8 (2.4, 209900) | 0.7995 |

| Tumor size (mean ± SD mm) | 39.25 ± 25.87 | 36.48 ± 25.52 | 0.4050 | 47.69 ± 29.26 | 51.53 ± 36.56 | 0.6369 |

| Solitary/Multiple | 60/28 | 122/63 | 0.7142 | 17/15 | 24/12 | 0.2546 |

| Vp (+/-) | 28/60 | 46/139 | 0.2271 | 13/19 | 16/20 | 0.7506 |

| T factor (T12/T34) | 48/40 | 108/77 | 0.5498 | 15/17 | 17/19 | 0.9772 |

| Recurrence (+/-) | 59/29 | 138/47 | 0.1934 | 20/12 | 20/16 | 0.5614 |

Among the C-HCC patients, the current smokers were slightly but significantly younger than the never + Ex patients (mean age 65.34 years vs 68.02 years, P = 0.0153) at the time of surgery. The current smokers showed significant male predominance (P < 0.0001) and had a significantly greater incidences of alcohol abuse (P < 0.0001). The BMI and ICG R15 values of the current smokers were both significantly lower than those of the never+Ex patients (P = 0.0031 and 0.0005, respectively). No significant difference was observed in diabetes mellitus, serum AFP level, tumor size, multiple tumor, Vp, T factor, or recurrence between the current smokers and the other patients.

In the B-HCC patient group, although the current smokers were significantly younger (mean age 53.66 years vs 60.25 years, P = 0.0284) and showed a significant male predominance (P = 0.0204), no significant difference was observed in any of the other factors between the current smokers and the other patients.

There have been many studies regarding cigarette smoking and the risk of developing HCC, and a recent meta-analysis confirmed the relationship between smoking and an increased risk of HCC development and mortality from HCC[12]. Including our previous study[11], there have been only a few studies focusing on the correlation between smoking status and the surgical outcomes of hepatectomy or liver transplantation for HCC[12-15]. The present study is the first to compare C-HCC and B-HCC regarding smoking status and surgical outcomes.

The most salient finding of this study is that the correlations between smoking status and surgical outcomes were notably different between the B-HCC and C-HCC patient groups. Although the current-smoking habit affected the surgical outcomes of the C-HCC patients, no significant association was found between smoking status and surgical outcomes in the B-HCC patients. As the current-smoking habit was revealed as an independent prognostic factor for both the OS and disease-specific survival in our C-HCC group, the tumors that had developed in the current smokers were indicated to have more aggressive malignant potential than the tumors that developed in the never- and ex-smokers. The continued elucidation of the pathological and molecular mechanisms underlying the development is a very important research focus, and we suspect that the difference in the natural histories of C-HCC and B-HCC is a key factor in the difference in the smoking status and surgical outcomes between B-HCC and C-HCC.

Generally, HCV-infected individuals develop HCC after long-term chronic hepatitis, and C-HCCs are typically found in patients with cirrhosis[16]. Activated inflammatory cells release reactive oxygen species and induce lipid peroxidation, which promotes a pro-oncogenic environment and DNA damage[17] and increases DNA methylation[18,19]. Thus, C-HCC develops mainly via an indirect pathway caused by chronic inflammation and an epigenetic process.

Although the mechanism of the carcinogenesis of HCC due to smoking has not been fully elucidated, it is reported that smoking yields chemicals with oncogenic potential such as hydrocarbons, nitrosamine, tar and vinyl chloride and a major source of 4-aminobiphenyl, a hepatic carcinogen which has been implicated as a causal risk factor for HCC[20]. These oncogenic chemicals covalently bind to DNA and form DNA adducts, which play a central role in the carcinogenic process by causing miscoding events in critical genes[21]. One hypothesis is that in current smokers, these genetic abnormalities due to smoking are superimposed on the natural course of C-HCC and thus highly malignant HCC develops. We suspect that this hypothesis will be verified by further studies in the near future.

Another interesting result of the present study is that smoking status was not correlated with DFS in the C-HCC group. Although this may be explained by the carcinogenesis via chronic HCV infection, it seems to contradict our finding that smoking habit was significantly associated with disease-specific survival. Two hypotheses that may explain this contradiction are as follows: (1) The malignant potential of recurrent tumors in the current smokers was higher than that in the other patients; and (2) the number of cases that had relapsed as a metastatic lesion of the resected primary tumor was larger in the current-smoker group compared to the never + Ex-smoker group. To elucidate this point clearly, it is crucial to analyze surgical outcomes based on detailed information regarding post-surgery smoking cessation. Quite regrettably, such data were not available in our database.

Although the inflammation and liver damage associated with chronic hepatitis B also introduce an accumulation of genetic and epigenetic alterations, a direct effect of HBV contributes to the development of B-HCC[2]. HBV genomes can integrate into the host genome and induce chromosomal alterations and insertional mutagenesis of cancer genes[22]. Therefore, B-HCC can develop in the absence of inflammation, which is in stark contrast to C-HCC development[23]. The reason for the different association of smoking status and surgical outcomes between the B-HCC and C-HCC groups may be caused by the differences in carcinogenesis via HBV infection and HCV infection. However, a study based in China that analyzed the surgical outcomes of 302 patients with B-HCC reported that smoking status was correlated with both HCC recurrence and HCC mortality[13]. Therefore, the reason why smoking status did not correlate with the surgical outcomes of B-HCC in the present study may be due simply to the small sample size of the B-HCC patients (n = 68, vs 273 C-HCC patients).

The results of our subgroup analyses of the C-HCC and B-HCC patients comparing the current-smoker patients and the other patients were also interesting. The analysis of the C-HCC group revealed that the current-smoker group developed HCC at significantly younger ages compared to the never+Ex group. The current-smoker group was similarly significantly younger in the B-HCC group. These results of the present study and our NBNC-HCC study[11] both showed that current smokers develop HCC at a younger age than other patients, which suggests an additive effect of smoking on the development of HCC irrespective of the virus infection status.

The limitations of the present study are retrospective-designed study, the small number of patients, and the long study period for enrollment. Information regarding post-surgery smoking status and treatment procedure for recurrent tumor were not available. Although we believe that our results provide important information to elucidate HCC’s natural history involving the patients’ lifestyle, our findings should be verified by investigations that include detailed smoking information, in large retrospective or prospective studies.

In conclusion, our present findings indicate that a current-smoking habit is significantly correlated with the overall and disease-specific survivals of patients with C-HCC. In contrast, our B-HCC patient group showed a weak association between current smoking and surgical outcomes. Our analyses also revealed that the current smokers were significantly younger than the other patients irrespective of hepatitis viral infection status.

Although cigarette smoking has been recognized as one of the risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the surgical outcomes and clinicopathological characteristics according to smoking habits of HCC patients remains unclear. We investigate the association between smoking status and surgical outcomes in hepatitis B virus-related HCC (B-HCC) and HCV-related HCC (C-HCC).

We recently analyzed the relationship between smoking status and surgical outcomes in patients with non-B non-C (NBNC)-HCC, and our analysis revealed that smoking habits are significantly correlated with the curatively resected surgical outcomes of NBNC-HCC. We then speculated that if smoking habits truly affect the postoperative prognosis of HCC, smoking habits might also affect the postoperative prognosis of viral-associated HCC patients.

We conducted the present study to investigate the association between smoking habits and surgical outcomes in B-HCC and C-HCC patients who underwent curative surgery, and clarify the clinicopathological features associated with smoking habits in patients with B-HCC or C-HCC.

Cases of the 341 consecutive patients with viral-associated HCC (C-HCC, n = 273; B-HCC, n = 68) who underwent curative surgery for their primary lesion were retrospectively examined. We categorized smoking status at the time of surgery into never, ex- and current smoker and analyzed the clinicopathological features and surgical outcomes, i.e., disease-free survival (DFS), overall survival (OS), and disease-specific survival (DSS).

The multivariate analysis in the C-HCC group revealed that current-smoker status was significantly correlated with both OS and DSS. No significant correlation was observed between current-smoker status and DFS, OS, or DSS in the B-HCC patients of the univariate or multivariate analyses.

Smoking habit is significantly correlated with the overall and disease-specific survivals of patients with C-HCC, and in contrast, the B-HCC patients showed a weak association between smoking status and surgical outcomes.

The results of this study support the hypothesis that smoking-associated HCC is with is high malignant potential. It would be a motivation for further research. We expect future research clarify the mechanism of carcinogenesis of HCC via smoking. Our results also can be expected to provide further motivation for smoking cessation.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Yu WB S- Editor: Chen K L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359-E386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20108] [Cited by in RCA: 20516] [Article Influence: 2051.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (20)] |

| 2. | Ringelhan M, McKeating JA, Protzer U. Viral hepatitis and liver cancer. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2017;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Umemura T, Ichijo T, Yoshizawa K, Tanaka E, Kiyosawa K. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44 Suppl 19:102-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | But DY, Lai CL, Yuen MF. Natural history of hepatitis-related hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1652-1656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhou Y, Si X, Wu L, Su X, Li B, Zhang Z. Influence of viral hepatitis status on prognosis in patients undergoing hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Utsunomiya T, Shimada M, Kudo M, Ichida T, Matsui O, Izumi N, Matsuyama Y, Sakamoto M, Nakashima O, Ku Y. A comparison of the surgical outcomes among patients with HBV-positive, HCV-positive, and non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma: a nationwide study of 11,950 patients. Ann Surg. 2015;261:513-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tateishi R, Okanoue T, Fujiwara N, Okita K, Kiyosawa K, Omata M, Kumada H, Hayashi N, Koike K. Clinical characteristics, treatment, and prognosis of non-B, non-C hepatocellular carcinoma: a large retrospective multicenter cohort study. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:350-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hara M, Tanaka K, Sakamoto T, Higaki Y, Mizuta T, Eguchi Y, Yasutake T, Ozaki I, Yamamoto K, Onohara S. Case-control study on cigarette smoking and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among Japanese. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:93-97. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Tanaka K, Tsuji I, Wakai K, Nagata C, Mizoue T, Inoue M, Tsugane S; Research Group for the Development and Evaluation of Cancer Prevention Strategies in Japan. Cigarette smoking and liver cancer risk: an evaluation based on a systematic review of epidemiologic evidence among Japanese. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006;36:445-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Koh WP, Robien K, Wang R, Govindarajan S, Yuan JM, Yu MC. Smoking as an independent risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1430-1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kai K, Koga H, Aishima S, Kawaguchi A, Yamaji K, Ide T, Ueda J, Noshiro H. Impact of smoking habit on surgical outcomes in non-B non-C patients with curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:1397-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Abdel-Rahman O, Helbling D, Schöb O, Eltobgy M, Mohamed H, Schmidt J, Giryes A, Mehrabi A, Iype S, John H. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for the development of and mortality from hepatocellular carcinoma: An updated systematic review of 81 epidemiological studies. J Evid Based Med. 2017;10:245-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhang XF, Wei T, Liu XM, Liu C, Lv Y. Impact of cigarette smoking on outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma after surgery in patients with hepatitis B. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lv Y, Liu C, Wei T, Zhang JF, Liu XM, Zhang XF. Cigarette smoking increases risk of early morbidity after hepatic resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:513-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mangus RS, Fridell JA, Kubal CA, Loeffler AL, Krause AA, Bell JA, Tiwari S, Tector J. Worse Long-term Patient Survival and Higher Cancer Rates in Liver Transplant Recipients With a History of Smoking. Transplantation. 2015;99:1862-1868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Trinchet JC, Ganne-Carrié N, Nahon P, N’kontchou G, Beaugrand M. Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C virus-related chronic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2455-2460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bartsch H, Nair J. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress in the genesis and perpetuation of cancer: role of lipid peroxidation, DNA damage, and repair. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2006;391:499-510. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Shih YL, Kuo CC, Yan MD, Lin YW, Hsieh CB, Hsieh TY. Quantitative methylation analysis reveals distinct association between PAX6 methylation and clinical characteristics with different viral infections in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Okamoto Y, Shinjo K, Shimizu Y, Sano T, Yamao K, Gao W, Fujii M, Osada H, Sekido Y, Murakami S. Hepatitis virus infection affects DNA methylation in mice with humanized livers. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:562-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | El-Zayadi AR. Heavy smoking and liver. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6098-6101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hecht SS. Lung carcinogenesis by tobacco smoke. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2724-2732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 345] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fattovich G, Stroffolini T, Zagni I, Donato F. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S35-S50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1691] [Cited by in RCA: 1793] [Article Influence: 85.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 23. | Buendia MA, Neuveut C. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;5:a021444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |