Published online Jan 7, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i1.104

Peer-review started: November 2, 2017

First decision: November 14, 2017

Revised: November 22, 2017

Accepted: November 27, 2017

Article in press: November 27, 2017

Published online: January 7, 2018

Processing time: 66 Days and 20.1 Hours

To retrospectively evaluate the safety and feasibility of surgical specimen extraction via a prophylactic ileostomy procedure in patient with rectal cancer.

We systematically reviewed 331 consecutive patients who underwent laparoscopic anterior resection for rectal cancer and prophylactic ileostomy in our institution from June 2010 to October 2016, including 155 patients who underwent specimen extraction via a prophylactic ileostomy procedure (experimental group), and 176 patients who underwent specimen extraction via a small lower abdominal incision (control group). Clinical data were collected from both groups and statistically analyzed.

The two groups were matched in clinical characteristics and pathological outcomes. However, mean operative time was significantly shorter in the experimental group compared to the control group (161.3 ± 21.5 min vs 168.8 ± 20.5 min; P = 0.001). Mean estimated blood loss was significantly less in the experimental group (77.4 ± 30.7 mL vs 85.9 ± 35.5 mL; P = 0.020). The pain reported by patients during the first two days after surgery was significantly less in the experimental group than in the control group. No wound infections occurred in the experimental group, but 4.0% of the controls developed wound infections (P = 0.016). The estimated 5-year disease-free survival and overall survival rate were similar between the two groups.

Surgical specimen extraction via a prophylactic ileostomy procedure represents a secure and feasible approach to laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery, and embodies the principle of minimally invasive surgery.

Core tip: Prophylactic ileostomy plays an important role in reducing the incidence of anastomotic leakage in rectal cancer patients. In this paper, we introduce an innovative method named surgical specimen extraction via a prophylactic ileostomy procedure and to evaluate its safety and feasibility.

- Citation: Wang P, Liang JW, Zhou HT, Wang Z, Zhou ZX. Surgical specimen extraction via a prophylactic ileostomy procedure: A minimally invasive technique for laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(1): 104-111

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i1/104.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i1.104

Rectal cancer patients with ultra-low anastomosis (anastomosis level ≤ 5 cm from the anal verge) have a high incidence of anastomotic leakage (AL), with the reported rates ranging from 9.4% to 12.3%[1-3]. In addition, several studies have shown that male sex (P < 0.001), body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2 (P = 0.05), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score ≥ 3 (P = 0.04), tumor size ≥ 5 cm (P = 0.05), preoperative chemoradiotherapy history (P = 0.02), long operative time (P = 0.0002), and number of stapler firings ≥ 3 (P < 0.001) are all risk factors for AL in rectal cancer patients[4-10]. AL is a serious complication in that it extends hospitalization time, increases expense, delays subsequent therapy, and increases perioperative mortality[5-7].

Studies show that prophylactic ileostomy plays an important role in reducing the incidence of AL in patients with one or more of the above-mentioned factors[11-14]. During conventional laparoscopic anterior resection of rectal cancer, a vertical or horizontal incision in the lower abdomen about 5 cm long was utilized to extract the specimen, and then a circular incision about 4 cm in diameter was made in the right lower quadrant to complete the ileostomy. With ongoing developments in minimally invasive surgery, we tried an innovative method at the National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College beginning in June 2010 that involved surgical specimen extraction through a prophylactic ileostomy procedure so as to avoid making a vertical or horizontal incision in the lower abdomen. Herein, we describe this surgical innovation and analyze its safety and feasibility.

The ethics committee at our institution approved this retrospective study, and it conformed to the ethical standards of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The data from all consecutive patients with rectal cancer who underwent laparoscopic anterior resection and prophylactic ileostomy in our institution from June 2010 to October 2016 were compiled and included in this study. All of these patients had been diagnosed with rectal cancer before undergoing surgery. Preoperative examinations, including routine blood tests, serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), chest radiography, electrocardiograms, abdominal and pelvic computed tomography scans, and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging, were used to evaluate the operative approach. The patients themselves selected the surgical procedure after the benefits and risks were explained explicitly. All of the surgeons in this study performed both types of surgery. The pathological specimens were examined by two pathologists who specialized in colorectal cancer.

Tumor staging was performed based on the criteria from the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) manual. Postoperative pain was evaluated by the patients using the “visual analog scale” (VAS) of 0 to 10, with 0 representing no pain and 10 representing the worst pain imaginable. Clinical characteristics, operative outcomes, pathological outcomes, postoperative complications, and follow-up information were recorded in our database.

In the operating room, anesthesia was induced, and the patient was placed in the modified lithotomy position for the laparoscopic procedure. A four or five-port technique was used. The surgeon and the camera operator stood on the right of the patient, while the assisting surgeon stood on the left. Abdominal inflation pressure was maintained at approximately 15 mmHg. Division of blood vessels, dissection of lymph nodes, and abscission of the distal intestine were then performed laparoscopically. Total mesorectal excision (TME) principles were followed.

In the experimental group, the specimen extraction was performed via an incision with a diameter of about 4.5 cm in the right lower quadrant, and then the surgical specimen was extracted. After abscising the proximal intestine and implanting the stapling head, the pneumoperitoneum was re-established, and a colorectal anastomosis was performed using a stapling technique. Finally, the ileostomy procedure was performed via the incision (Figure 1A). In the control group, a vertical or horizontal incision with a length of about 5 cm was made in the lower abdomen to extract the specimen, and an anastomosis was done by the same method as in the experimental group, and then a circular incision with a diameter of about 4 cm was performed in the right lower quadrant to complete the ileostomy procedure (Figure 1B).

The single-use incision protectors were used to protect incisions from pollution or cancer cell implantation for both procedures when taking out the surgical specimen via the incision. Laparoscopic surgery had been planned for all of the patients, but it was necessary to convert several of the procedures to open surgery.

After hospital discharge, patients were advised to have follow-up monitoring by their doctors every 3 mo during the first 2 years, every 6 mo for the next 3 years, and then yearly visits after 5 years. The beginning of the follow-up time was set at the first day after surgery, and the end was set at June 30, 2017.

The positive circumferential resection margin (CRM) was considered as microscopic tumor less than 1 mm from the mesorectal fascia. Disease free survival (DFS) was defined as the period from surgery to death or disease recurrence. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the period from surgery to death.

Patients who required conversion were included in their intended group, because the data were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis. Quantitative data that were normally distributed are presented as mean ± SD, and were analyzed by the Student’s t-test. Categorical data are presented as number and percentage, and were analyzed by the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. Survival analysis was performed by the Kaplan-Meier method, and survival was compared by the log-rank test. All the tests were two-sided, with a P-value < 0.05 used as the threshold for statistical significance. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0 for Windows (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States) was used for data analyses.

A total of 331 consecutive cases were included in our study, including 155 (46.8%) cases in the experimental group and 176 (53.2%) in the control group. There were no significant differences in terms of gender, age, BMI, ASA score, or history of neoadjuvant chemoradiation between two groups (Table 1). No deaths occurred during the perioperative period.

| Characteristic | Experimental group (n = 155) | Control group (n = 176) | P value |

| Gender | 0.842 | ||

| Male | 88 (56.8) | 98 (55.7) | |

| Female | 67 (43.2) | 78 (44.3) | |

| Age (yr; mean ± SD) | 55.5 ± 12.2 | 57.0 ± 11.6 | 0.250 |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 23.9 ± 2.5 | 24.4 ± 3.1 | 0.171 |

| ASA score | |||

| 1 | 40 (25.8) | 47 (26.7) | 0.857 |

| 2 | 79 (51.0) | 82 (46.6) | |

| 3 | 31 (20.0) | 41 (23.3) | |

| 4 | 5 (3.2) | 6 (3.4) | |

| Neoadjuvant chemoradiation | |||

| Yes | 48 (31.0) | 52 (29.5) | 0.811 |

| No | 107 (69.0) | 124 (70.5) |

Operative outcomes are shown in Table 2. Mean operative time was significantly shorter in the experimental group compared with the control group (161.3 ± 21.5 min vs 168.8 ± 20.5 min, P = 0.001). Mean estimated blood loss was significantly less in the experimental group than in the control group (77.4 ± 30.7 mL vs 85.9 ± 35.5 mL, P = 0.020). The mean diameter of the stoma was significantly larger in the experimental group (4.7 ± 0.5 cm vs 4.0 ± 0.6 cm, P < 0.001). The pain on the VAS reported by patients in the experimental group during the first two days after surgery was significantly reduced compared to the control group (P < 0.001 and P = 0.012, respectively). There were no significant differences in time to first flatus, time to first oral intake, or postoperative hospitalization. There were five and six cases of conversion to open surgery in the experimental group and the control group, respectively (P = 1.000).

| Variable | Experimental group (n = 155) | Control group (n = 176) | P value |

| Operating time (min; mean ± SD) | 161.3 ± 21.5 | 168.8 ± 20.5 | 0.001 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL; mean ± SD) | 77.4 ± 30.7 | 85.9 ± 35.5 | 0.020 |

| Diameter of stoma (cm; mean ± SD) | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | < 0.001 |

| Time to first flatus (d; mean ± SD) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 0.586 |

| Time to first oral intake (d; mean ± SD) | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 0.062 |

| Postoperative hospitalization (d; mean ± SD) | 6.3 ± 1.3 | 6.5 ± 1.2 | 0.199 |

| Postoperative pain score (mean ± SD) | |||

| The first day | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 |

| The second day | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 0.012 |

| The third day | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 0.628 |

| No. of conversions to open surgery (%) | 5 (3.2) | 6 (3.4) | 1.000 |

Pathological results are summarized in Table 3. There were no significant differences in the findings, including tumor size, lengths of the proximal and distal resection margins, number of lymph nodes harvested, and number of patients with < 12 lymph nodes harvested, differentiation degree, pathological patterns, nerve and vessel invasion, or pTNM stage. There were no cases with positive distal margins or positive CRM in either group.

| Variable | Experimental group (n = 155) | Control group (n = 176) | P value |

| Tumor size (cm; mean ± SD) | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 0.205 |

| Proximal resection margin (cm; mean ± SD) | 16.2 ± 7.1 | 15.4 ± 7.3 | 0.309 |

| Distal resection margin (cm; mean ± SD) | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 0.477 |

| No. of lymph nodes harvested (mean ± SD) | 22.8 ± 5.3 | 21.7 ± 5.0 | 0.375 |

| No. of patients with lymph nodes harvested < 12 | 10 (6.5) | 13 (7.4) | 0.830 |

| Differentiation degree | 0.963 | ||

| Good | 45 (29.0) | 50 (28.4) | |

| Moderate | 62 (40.0) | 73 (41.5) | |

| Poor | 48 (31.0) | 53 (30.1) | |

| Pathological pattern | 0.785 | ||

| Canalicular adenocarcinoma | 108 (69.7) | 125 (71.0) | |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 25 (16.1) | 22 (12.5) | |

| Papillary adenocarcinoma | 12 (7.7) | 16 (9.1) | |

| Signet-ring carcinoma | 10 (6.5) | 13 (7.4) | |

| Nerve invasion | 30 (19.4) | 37 (21.0) | 0.706 |

| Vessel invasion | 26 (16.8) | 30 (17.0) | 0.948 |

| Positive distal margin | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Positive CRM | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| pTNM stage | 0.807 | ||

| I | 38 (24.5) | 45 (25.6) | |

| II | 61 (39.4) | 70 (39.8) | |

| III | 44 (28.4) | 52 (29.5) | |

| IV | 12 (7.7) | 9 (5.1) |

Postoperative complications are summarized in Table 4. Although the average diameter of the stoma was larger in the experimental group, there were no statistically significant differences in the incidence of stoma-related complications, including infections, retractions, bleeding, or parastomal hernia. The incidence of wound infections was lower in the experimental group than in the control group (0% vs 4.0%, P = 0.016). Three patients underwent reestablishment of stoma because of stoma necrosis, and five patients underwent debridement and suturing procedure because of incision infection in the control group. No statistical differences were found with respect to intestinal obstruction, urinary retention, cardiopulmonary complications, or re-operation.

| Variable | Experimental group (n = 155) | Control group (n = 176) | P value |

| Stoma related | |||

| Stoma edema | 15 (9.7) | 18 (10.2) | 0.868 |

| Stoma infection | 4 (2.6) | 2 (1.1) | 0.326 |

| Stoma retraction | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0.468 |

| Stoma necrosis | 0 (0) | 3 (1.7) | 0.251 |

| Stoma fistula | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 1.000 |

| Stoma bleeding | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0.468 |

| Stoma stenosis | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) | 0.501 |

| Skin inflammation around the stoma | 16 (10.3) | 16 (9.1) | 0.705 |

| Parastomal hernia | 4 (2.6) | 2 (1.1) | 0.424 |

| Mucosal prolapse | 3 (1.9) | 2 (1.1) | 0.668 |

| Wound infection | 0 (0) | 7 (4.0) | 0.016 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 1 (0.6) | 3 (1.7) | 0.626 |

| Retention of urine | 3 (1.9) | 3 (1.7) | 1.000 |

| Cardiopulmonary | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 1.000 |

| Re-operation | 1 (0.6) | 8 (4.5) | 0.220 |

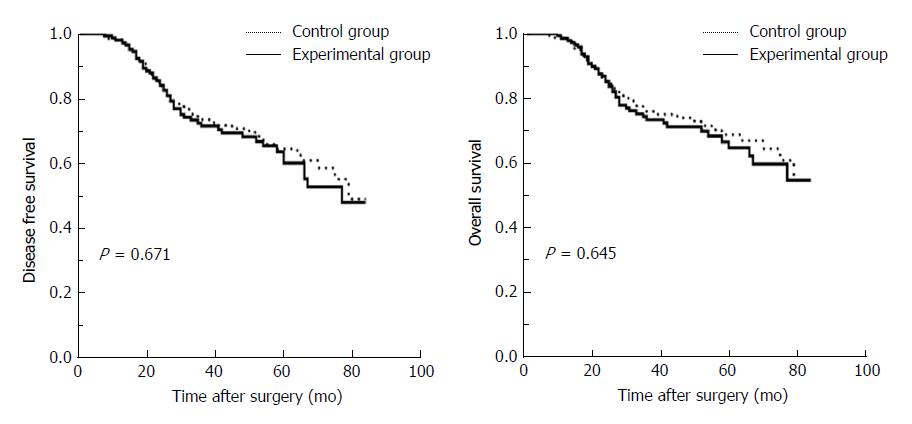

The mean follow-up period was 40 mo (range 7-84 mo) in the experimental group and 41 mo (range 6-84 mo) in the control group (P = 0.781). No patients suffered from local recurrence in the specimen extraction sites in both groups. The estimated 5-year DFS rate was 60.0% in the experimental group and 64.5% in the control group (P = 0.671). The estimated 5-year OS rate was 64.8% in the experimental group and 68.8% in the control group (P = 0.645) (Figure 2).

With increased life expectancy and improved standards of living, the incidence of rectal cancer is increasing in China[15]. The most distinguishing feature of rectal cancer in the Chinese population is that the majority (60%-75%) are lower rectal cancer, which has higher proportions than those reported in Western populations[16,17]. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for rectal cancer. In the past, abdominoperineal resection was the standard of care, with sigmoidostomy negatively impacting the patients’ quality of life. At present, the exciting prospect is that there is an increased probability of successfully performing re-anastomosis and anal-sparing procedures for patients with lower rectal cancer as a result of the advances in surgical technology and improvements in operative procedures[18,19].

However, the possibility of AL is greater for cases with ultra-low anastomoses, which can increase the perioperative mortality and affect long-term survival. There are not only procedure-related factors, such as longer operative time, ≥ 3 stapler firings, and ultra-low anastomosis, but also demographic risk factors, such as male sex, BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, ASA score ≥ 3, tumor size ≥ 5 cm, or a history of preoperative chemoradiotherapy. These all have proven to be risk factors for AL in rectal cancer patients[4-10].

Several studies[20-23] reported the effects of the use of rectal tubes on the occurrence of AL, but the results of a meta-analysis[4] indicated that there was no statistically significant association (OR = 0.48; 95%CI: 0.20-1.12, P = 0.09). Thus, it appears that postoperative AL cannot be reliably prevented by placement of a rectal tube only. Prophylactic ileostomy procedure has been widely adopted to prevent AL and its impact on decreasing this adverse outcome has been widely verified[11-14]. The rectal cancer surgery reported here tends to dissociate the rectum laparoscopically and extracts specimens via a small incision. In our study, we combined extracting the surgical specimen and performing the prophylactic ileostomy procedure at the outset. Therefore, the small incision was not employed. In theory, this approach embodies the benefits of minimally invasive surgery.

In our study, the primary results indicated that patients in the experimental group had a decreased incidence of wound infections (0% vs 4.0%, P = 0.016), and less pain during the first two postoperative days (2.6 ± 0.8 vs 3.1 ± 1.1, P < 0.001 on day 1; 1.6 ± 0.6 vs 1.8 ± 0.7, P = 0.012 on day 2) compared with the control group. In addition, compared with the patients in the control group, patients in the experimental group had shorter operative time (161.3 ± 21.5 min vs 168.8 ± 20.5 min, P = 0.001) and less estimated blood loss (77.4 ± 30.7 mL vs 85.9 ± 35.5 mL, P = 0.020). Although the stoma had larger average diameter in the experimental group than in the control group (4.7 ± 0.5 cm vs 4.0 ± 0.6 cm, P < 0.001), stoma-related complications (including infections, retractions, bleeding, and edema) were not increased. Four cases in the experimental group suffered from parastomal hernias, but they recuperated after the procedure to close the ileostomy. No patients suffered from positive distal margin complications or CRM in either group. Thus, the results of the present study support the safety and efficacy of this procedure.

In this study, we would like to emphasize that a single-use incision protector should be used to protect incision from pollution or cancer cell implantation when taking out the surgical specimen via the incision, and the ileostomy incision should not be too small so that the specimen is squeezed. It is also crucial to stress that, when suturing the skin and intestinal wall, the stoma should be constructed to avoid retraction (Figure 1A). In addition, the descending colon should be dissected and fully freed up to ensure enough length is available for re-anastomosis at the margin of the proximal resection.

Although the use of the ileostomy site as the specimen extraction site has already been described in patients with inflammatory bowel disease[24,25], the use in rectal cancer has not been reported. This was a retrospective study, in which all the laparoscopic procedures were performed by different surgeons independently, based on their own considerations, preferences and clinical judgement. Therefore, bias may exist. However, we have included a large sample and a long follow-up time. In addition, the two groups were well balanced in clinical characteristics and pathological findings which may have influenced the results. We hope that further randomized prospective controlled trials will be conducted to confirm our results in the near future.

In conclusion, surgical specimen extraction via a prophylactic ileostomy procedure represents a secure and feasible approach to laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery, and embodies the principle of minimally invasive surgery.

A vertical or horizontal incision in the lower abdomen about 5 cm long was utilized to extract the specimen, and then a circular incision about 4 cm in diameter was made in the right lower quadrant to complete the ileostomy for rectal cancer patients who accept prophylactic ileostomy. With ongoing developments in minimally invasive surgery, we tried an innovative method that involved surgical specimen extraction through a prophylactic ileostomy procedure so as to avoid making a vertical or horizontal incision in the lower abdomen. This procedure has not been reported in rectal cancer patients.

The purpose of this study was to compare and analyze the short and long-outcomes of surgical specimen extraction via a prophylactic ileostomy procedure vs a small lower abdominal incision procedure. The significance of this study is to inaugurate a more minimally invasive method for rectal cancer patients who accept prophylactic ileostomy.

The study aimed to evaluate the safety and feasibility of surgical specimen extraction via a prophylactic ileostomy procedure in patients with rectal cancer.

Rectal cancer patients who accepted laparoscopic anterior resection and prophylactic ileostomy were systemically reviewed from June 2010 to October 2016 in our institution. Clinical characteristics, operative outcomes, pathological outcomes, postoperative complications, and follow-up information were collected and analyzed using SPSS version 21.0.

The results showed that mean operative time was significantly shorter in the experimental group compared to the control group (P = 0.001). Mean estimated blood loss was significantly less in the experimental group (P = 0.020). The pain reported by patients in the experimental group was significantly less than that of the controls during the first two days after surgery (P < 0.001 and P = 0.012, respectively). Postoperative complications did not increase. The estimated 5-year disease-free survival and overall survival rates were similar between the two groups (P = 0.671 and P = 0.645, respectively).

Surgical specimen extraction via a prophylactic ileostomy procedure represents a secure and feasible approach to laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery, and embodies the principle of minimally invasive surgery.

In this study, we would like to emphasize that a single-use incision protector should be used to protect incision from pollution or cancer cell implantation when taking out the surgical specimen via the incision, and the ileostomy incision should not be too small so that the specimen is squeezed. This was a retrospective study, and bias may exist. We hope that further randomized prospective controlled trials will be conducted to confirm our results in the near future.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P- Reviewer: Luglio G, Parellada CM, Shigeta K, Sterpetti AV S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Lim DR, Hur H, Min BS, Baik SH, Kim NK. Colon Stricture After Ischemia Following a Robot-Assisted Ultra-Low Anterior Resection With Coloanal Anastomosis. Ann Coloproctol. 2015;31:157-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kim JC, Yu CS, Lim SB, Kim CW, Park IJ, Yoon YS. Outcomes of ultra-low anterior resection combined with or without intersphincteric resection in lower rectal cancer patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1311-1321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Seo SI, Lee JL, Park SH, Ha HK, Kim JC. Assessment by Using a Water-Soluble Contrast Enema Study of Radiologic Leakage in Lower Rectal Cancer Patients With Sphincter-Saving Surgery. Ann Coloproctol. 2015;31:131-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Qu H, Liu Y, Bi DS. Clinical risk factors for anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic anterior resection for rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:3608-3617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang W, Lou Z, Liu Q, Meng R, Gong H, Hao L, Liu P, Sun G, Ma J, Zhang W. Multicenter analysis of risk factors for anastomotic leakage after middle and low rectal cancer resection without diverting stoma: a retrospective study of 319 consecutive patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:1431-1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rojas-Machado SA, Romero-Simó M, Arroyo A, Rojas-Machado A, López J, Calpena R. Prediction of anastomotic leak in colorectal cancer surgery based on a new prognostic index PROCOLE (prognostic colorectal leakage) developed from the meta-analysis of observational studies of risk factors. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:197-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ashburn JH, Stocchi L, Kiran RP, Dietz DW, Remzi FH. Consequences of anastomotic leak after restorative proctectomy for cancer: effect on long-term function and quality of life. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:275-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lim SB, Yu CS, Kim CW, Yoon YS, Park IJ, Kim JC. Late anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection in rectal cancer patients: clinical characteristics and predisposing factors. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:O135-O140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ji WB, Kwak JM, Kim J, Um JW, Kim SH. Risk factors causing structural sequelae after anastomotic leakage in mid to low rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5910-5917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Boyce SA, Harris C, Stevenson A, Lumley J, Clark D. Management of Low Colorectal Anastomotic Leakage in the Laparoscopic Era: More Than a Decade of Experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:807-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shiomi A, Ito M, Saito N, Hirai T, Ohue M, Kubo Y, Takii Y, Sudo T, Kotake M, Moriya Y. The indications for a diverting stoma in low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a prospective multicentre study of 222 patients from Japanese cancer centers. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:1384-1389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Güenaga KF, Lustosa SA, Saad SS, Saconato H, Matos D. Ileostomy or colostomy for temporary decompression of colorectal anastomosis. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Cir Bras. 2008;23:294-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Miyo M, Takemasa I, Hata T, Mizushima T, Doki Y, Mori M. Safety and Feasibility of Umbilical Diverting Loop Ileostomy for Patients with Rectal Tumor. World J Surg. 2017;41:3205-3211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Azin A, Le Souder E, Urbach D, Okrainec A, Chadi SA, Quereshy F, Jackson TD, Elnahas A. The safety and feasibility of early discharge following ileostomy reversal: a National Surgical Quality Improvement Program analysis. J Surg Res. 2017;217:247-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zeng WG, Zhou ZX, Hou HR, Liang JW, Zhou HT, Wang Z, Zhang XM, Hu JJ. Outcome of laparoscopic versus open resection for rectal cancer in elderly patients. J Surg Res. 2015;193:613-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:115-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11444] [Cited by in RCA: 13210] [Article Influence: 1467.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 17. | Zhang XM, Liang JW, Wang Z, Kou JT, Zhou ZX. Effect of preoperative injection of carbon nanoparticle suspension on the outcomes of selected patients with mid-low rectal cancer. Chin J Cancer. 2016;35:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dayal S, Battersby N, Cecil T. Evolution of Surgical Treatment for Rectal Cancer: a Review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:1166-1173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tang B, Zhang C, Li C, Chen J, Luo H, Zeng D, Yu P. Robotic Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer: A Series of 392 Cases and Mid-Term Outcomes from A Single Center in China. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:569-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kawada K, Hasegawa S, Hida K, Hirai K, Okoshi K, Nomura A, Kawamura J, Nagayama S, Sakai Y. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic low anterior resection with DST anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2988-2995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Goto S, Hida K, Kawada K, Okamura R, Hasegawa S, Kyogoku T, Ota S, Adachi Y, Sakai Y. Multicenter analysis of transanal tube placement for prevention of anastomotic leak after low anterior resection. J Surg Oncol. 2017; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Akiyoshi T, Ueno M, Fukunaga Y, Nagayama S, Fujimoto Y, Konishi T, Kuroyanagi H, Yamaguchi T. Incidence of and risk factors for anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic anterior resection with intracorporeal rectal transection and double-stapling technique anastomosis for rectal cancer. Am J Surg. 2011;202:259-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hidaka E, Ishida F, Mukai S, Nakahara K, Takayanagi D, Maeda C, Takehara Y, Tanaka J, Kudo SE. Efficacy of transanal tube for prevention of anastomotic leakage following laparoscopic low anterior resection for rectal cancers: a retrospective cohort study in a single institution. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:863-867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dumont F, Goéré D, Honoré C, Elias D. Transanal endoscopic total mesorectal excision combined with single-port laparoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:996-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Benlice C, Gorgun E. Single-port laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy with ileal-pouch anal anastomosis using a left lower quadrant ileostomy site - a video vignette. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:818-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |