Published online Mar 7, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i9.1645

Peer-review started: December 2, 2016

First decision: December 28, 2016

Revised: January 12, 2017

Accepted: February 7, 2017

Article in press: February 8, 2017

Published online: March 7, 2017

Processing time: 95 Days and 24 Hours

To demonstrate the clinical outcomes of a multicenter experience and to suggest guidelines for choosing a suction method.

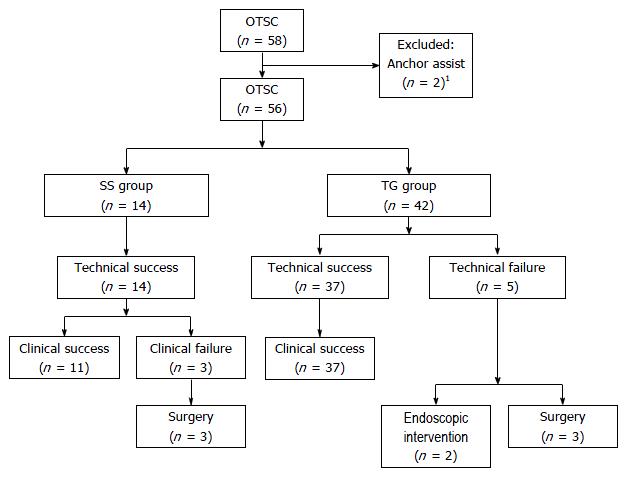

This retrospective study at 5 medical centers involved 58 consecutive patients undergoing over-the-scope clips (OTSCs) placement. The overall rates of technical success (TSR), clinical success (CSR), complications, and procedure time were analyzed as major outcomes. Subsequently, 56 patients, excluding two cases that used the Anchor device, were divided into two groups: 14 cases of simple suction (SS-group) and 42 cases using the Twin Grasper (TG-group). Secondary evaluation was performed to clarify the predictors of OTSC success.

The TSR, CSR, complication rate, and median procedure time were 89.7%, 84.5%, 1.8%, and 8 (range 1-36) min, respectively, demonstrating good outcomes. However, significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of the mean procedure time (5.9 min vs 14.1 min). The CSR of the SS- and TG-groups among cases with a maximum defect size ≤ 10 mm and immediate or acute refractory bleeding was 100%, which suggests that SS is a better method than TG in terms of time efficacy. The CSR in the SS-group (78.6%), despite the technical success of the SS method (TSR, 100%), tended to decrease due to delayed leakage compared to that in the TG-group (TSR, CSR; 88.1%), indicating that TG may be desirable for leaks and fistulae with defects of the entire layer.

OTSC system is a safe and effective therapeutic option for gastrointestinal defects. Individualized selection of the suction method based on particular clinical conditions may contribute to the improvement of OTSC success.

Core tip: The efficacy of over-the-scope clips (OTSCs) for gastrointestinal defects has been widely known. However, few large studies with more than 50 cases have been performed. Additionally, an optimal strategy for selecting a suction method, which is a critical factor of OTSC success, is needed. This study, with a large number of cases and a multicenter design, demonstrated excellent outcomes of OTSC and revealed which type of suction method was appropriate for particular situations according to the following characteristics: defect size, duration since onset, and indication. The individualized choice of the suction method is the most important factor determining OTSC success.

- Citation: Kobara H, Mori H, Fujihara S, Nishiyama N, Chiyo T, Yamada T, Fujiwara M, Okano K, Suzuki Y, Murota M, Ikeda Y, Oryu M, AboEllail M, Masaki T. Outcomes of gastrointestinal defect closure with an over-the-scope clip system in a multicenter experience: An analysis of a successful suction method. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(9): 1645-1656

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i9/1645.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i9.1645

Conventional endoscopic therapy-resistant gastrointestina diseases have traditionally required invasive surgery. These diseases mainly consist of GI refractory bleeding and leaks, including perforations, anastomotic leakage, and fistulae, which are encountered during endoscopic evaluation and are related to significant morbidity and mortality[1]. Recently, with the development of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD)[2] and natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES)[3], technological advances in endoscopic devices have allowed for the endoscopic closure of GI defects. Among several full-thickness suturing devices[4,5], the over-the-scope clip (OTSC) (Ovesco Endoscopy GmbH, Tübingen, Germany) has the advantage of rapid and convenient use in rescue therapy. Currently, many case reports[6-10] and preliminary case series[11-14] have reported on the efficacy of OTSCs for the closure of GI defects, eliminating the need for invasive surgery.

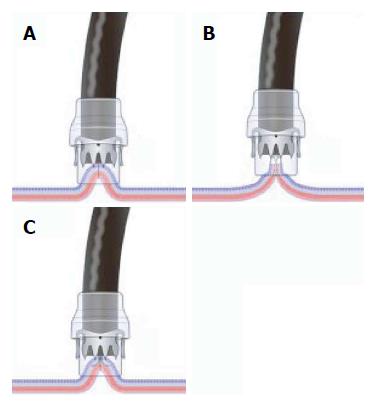

However, there are few studies that have used large samples[15], and few randomized controlled trials[16,17] have been performed with OTSCs. Specifically, a strategy for choosing a suction method into the application cap of the OTSC system has not been clearly described. Successful OTSC closure depends on the secure suction of the target lesion into the application cap. The options available for OTSC closure include three suction methods, including simple suction (SS), which is similar to endoscopic variceal band ligation, and two accessory devices (Ovesco Endoscopy GmbH), which are referred to as the Twin Grasper (TG) and the tissue-anchoring device called the Anchor. Functioning as grasping forceps, the TG is applied to easily approximate the grasping edges of a large lesion, whereas the Anchor can better approximate indurated tissue. As both devices are expensive, selection of the appropriate suction method needs to be made according to the characteristics of the target lesion, which include the size of the defect, indications, and the duration since onset. The primary goal of this study was to demonstrate clinical outcomes of a multicenter experience with OTSCs for the management of GI refractory bleeding, leaks, and fistulae. The secondary goals were to propose a directional strategy for choosing a suction method into the application cap of the OTSC system by comparing the clinical data of SS to that of TG.

This retrospective study was conducted at 5 medical centers in the Shikoku area of Japan. Between November 2011 and November 2015, fifty-eight patients who underwent attempted OTSC placement for GI refractory bleeding, leaks, or fistulae were enrolled. The detailed clinical data are summarized in Table 1. Patient characteristics, including age, indications with details, location of the defect, maximum defect size (D, mm), duration from onset to OTSC placement (immediate, ≤ 1 d, acute, 1-7 d, or chronic, > 7 d), and the numbers of OTSC deployments, were collected. The indication for OTSC application for GI nonvariceal and refractory bleeding was defined as cases in which 2 time trials by conventional interventions failed to achieve complete hemostasis. Perforations, deep defects of the gut with the risk of delayed perforations, and anastomotic leakages were included as leaks. Subsequently, 56 patients, excluding two cases that used the Anchor, were divided into two groups: 14 cases of simple suction (SS-group) vs 42 cases using the Twin Grasper (TG-group). All of the data were extracted and compiled into a central database at Kagawa University. Written informed consents related to the use of OTSCs were obtained from all patients. The Clinical Ethics Committee of Kagawa University Hospital and each institution approved this study. This study was registered under UMIN 000017767.

| Characteristics | Details | Total patients (n = 58) |

| Age, median (range), yr | 77 (37-98) | |

| Indications, n | ||

| Refractory bleeding | 18 | |

| Ulcer (peptic, Behçet's, anastomosis) | 12 | |

| Mallory-Weiss tear | 1 | |

| Diverticula | 2 | |

| Post-endoscopic resection | 3 | |

| Leaks | 28 | |

| Peptic ulcer | 3 | |

| Boerhaave | 1 | |

| Iatrogenic (ESD) | 16 | |

| Iatrogenic (ERCP) | 2 | |

| Iatrogenic (surgery) | 4 | |

| Iatrogenic (other) | 2 | |

| Fistula | 12 | |

| PEG | 6 | |

| Rectum-bladder | 1 | |

| Rectum-pelvis | 2 | |

| Gastric tube-trachea | 1 | |

| Gastric-pseudopancreatic cyst | 1 | |

| Colon-gallbladder | 1 | |

| Location, n | ||

| Esophagus | 3 | |

| Stomach | 28 | |

| Duodenum | 13 | |

| Small intestine | 2 | |

| Colon | 12 | |

| Maximum defect size (D) mm, n | ||

| D ≤ 10 | 25 | |

| 10 < D ≤ 20 | 9 | |

| 20 < D | 24 | |

| Median (range), mm | 15 (3-50) | |

| Duration since onset to OTSC placement, n | ||

| Immediate ≤ 1 d | 25 | |

| 1 < Acute ≤ 7 d | 11 | |

| Chronic > 7 d | 22 | |

| Suction method into the applicator cap | ||

| Simple suction | 14 | |

| Twin Grasper (TG) assist | 42 | |

| Anchor assist | 2 | |

| The number of OTSC deployments, n | ||

| 0 | 21 | |

| 1 | 39 | |

| 2 | 12 | |

| 3 | 5 |

The OTSC system is primarily composed of an OTSC mounted onto an application cap and a hand wheel. Users can easily apply the simple mechanism. As previously reported[18], the OTSC procedure involved several steps. First, the endoscope on which the cap with the loaded OTSC was mounted was inserted into the GI tract either orally or anally. Either a gastroscope (GIF-Q260J, ø 9.9 mm or H260Z, ø 10.8 mm Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or a colonoscope (PCF-Q260AI, ø 11.3 mm, Olympus) with a maximum diameter of 9.9 mm and a working channel with greater than a 2.8 mm diameter was applied. Second, the defect in the GI tract was sucked to an application cap using SS or application aids such as the TG or the Anchor. The choice of the suction method ultimately depended on the discretion of the operator in this study. Finally, the clip was fired by stretching the wire with the hand wheel, and the entire defect of the lesion was completely closed. The OTSC procedures for the SS and TG methods and the Anchor assist are shown as schemas in Figure 1. Additional OTSCs were deployed until the defect was entirely closed. Regarding the types of OTSCs that were used, the gastrostomy closure type for gastric walls and the traumatic (t) type for other organs with thin walls were introduced, depending on the lesion and the assessment of the operator; the atraumatic (a) type was not used in this study. Six expert endoscopists (H.K., H.M., T.Y., N.N., M.M., and M.O.) who had gained experience with the OTSC system procedure in a porcine model during a hands-on seminar session performed the OTSC deployments.

Major outcomes: The overall rates of technical success (TSR), clinical success (CSR), complications, and procedure time of the 58 patients were examined. Technical success was defined as the complete closure of the entire defect by the successful deployment of OTSCs. Clinical success was defined as the resolution of the troubled situation by the assessment of blood analysis, endoscopic, and/or radiographic imaging (surgery or further endoscopic intervention was not required during at least 1 mo of follow-up after OTSC placement). The procedure time of the suction method was defined as the duration between the attempts at aspiration or the application of the TG or Anchor on the target lesion and complete closure of the defect with OTSC placement, as reviewed by endoscopic images and/or movies. The number of OTSC placements per single defect was calculated when the entire defect of the lesion was completely closed.

Secondary outcomes: A secondary evaluation was performed to clarify the predictors of OTSC success in the SS- and TG-groups. The TSR, CSR, procedure time, and complication rates of both groups were compared.

Subsequently, the TSR and CSR of each parameter and the indications, location of the defect, maximum defect size (≤ 10, 10-20, or > 20 mm), and duration since onset (immediate, acute, or chronic) were compared between the SS- and TG-groups. We supposed that a maximum defect size of 10 mm might be suitable for complete closure in the SS-group, considering the caliber of the application cap (11 or 12 mm in diameter). Previous studies have shown that factors that promote OTSC failure include a large defect size (greater than 20 mm)[14], fibrosis of the target tissue, such as a fistula, and the duration from onset to OTSC placement[15]. Thus, the maximum defect size was defined using the cut-off values of 10 and 20 mm, and the duration from onset was evaluated as one parameter. Simultaneously, the CSRs in both groups in terms of the combined parameters, the defect size, and the duration since the onset of each indication were estimated to better clarify the quality of each method.

Normally distributed data are presented as medians and ranges. The TSRs, CSRs and complication rates in the SS- and TG-groups were compared using two-sided Fisher's exact tests. The mean procedure times of both methods were compared using two-sided Wilcoxon/Kruskal-Wallis tests. The TSRs and CSRs of each parameter were compared using a χ2 test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using JMP version 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

The results for the major outcomes are summarized in Table 2. The TSR and CSR were 89.7% and 84.5%, respectively. The complication rate was 1.8% in the 56 cases analyzed. The median procedure time (range) was 8 (1-36) min in 52 successful cases. Additionally, the TSR and CSR of each parameter are shown in Table 3. While the TSR decreased as defect size and duration since onset increased, the CSR decreased as duration since onset increased.

| Outcomes | Total patients (n = 58) |

| Technical success rate, % (95%CI) | 89.7 (81.0-98.4) |

| Clinical success rate, % (95%CI) | 84.5 (74.3-94.7) |

| Complications, n (%) | 1 (1.8) in 56 cases used |

| The procedure time, median (range), min | 8 (1-36) in 52 successful cases |

| Parameters | Total patients (n = 58) | |

| Technical success rate | Clinical success rate | |

| Indications | ||

| Refractory bleeding | 88.9 (16/18) | 83.3 (15/18) |

| Leak | 89.3 (25/28) | 85.7 (24/28) |

| Fistula | 91.7 (11/12) | 83.3 (10/12) |

| Location | ||

| Upper GI tract | 86.4(38/44) | 81.8 (36/44) |

| Lower GI tract | 100 (14/14) | 92.9 (13/14) |

| Maximum defect size (D), mm | ||

| D ≤ 10 | 96 (24/25) | 84 (21/25) |

| 10 < D ≤ 20 | 88.9 (8/9) | 88.9 (8/9) |

| 20 < D | 83.3 (20/24) | 83.3 (20/24) |

| Duration since onset, % (n) | ||

| Immediate ≤ 1 d | 96 (24/25) | 96 (24/25) |

| 1 < Acute ≤ 7 d | 90.9 (10/11) | 81.8 (9/11) |

| Chronic > 7 d | 81.8 (18/22) | 72.7 (16/22) |

| Suction method into the applicator cap | ||

| Simple suction (SS) | 100 (14/14) | 78.6 (11/14) |

| Twin Grasper (TG) Anchor assist | 88.1 (37/42) 50 (1/2) | 88.1 (37/42) 50 (1/2) |

| The number of OTSC deployments, n | ||

| 1 | 92.3 (36/39) | 84.6 (33/39) |

| 2 | 100 (12/12) | 100 (12/12) |

| 3 | 80 (4/5) | 80 (4/5) |

The results of the comparison between the SS- and TG-groups with respect to the major outcomes are summarized in Table 4. No significant differences were identified between the SS- and TG-groups in terms of TSR [100% (14/14) vs 88.1% (37/42), respectively] and CSR [78.6% (11/14) vs 88.1% (37/42), respectively], P > 0.05). However, the CSR in the SS-group [78.6% (11/14)], despite the technical success of the procedure (TSR, 100%), tended to decrease compared to that in the TG-group (TSR, CSR; 88.1%). Additionally, no significant differences were identified between the two groups in terms of the rate of complications [0% (0/14) vs 2.4% (1/42), P > 0.05]. However, significant differences were observed between the two groups regarding the mean procedure time (SS, 5.9 vs TG, 14.1 min, P < 0.05). A flow diagram of patient enrollment and outcomes is illustrated in Figure 2.

There were no significant differences in the TSRs and CSRs between the two groups for any parameter (P > 0.05) (Table 5). The CSR in the TG-group decreased as defect size and duration since onset increased. The CSRs of the combined parameters, defect sizes and duration since onset in each indication are summarized in Table 6. For refractory bleeding, the CSRs for cases of D ≤ 10 were 85.7% (6/7) in the SS-group and 100% (2/2) in the TG-group. The CSR of the SS- and TG-groups among cases with D ≤ 10 and immediate or acute refractory bleeding was 100%, which suggested that SS is a better method than TG in terms of time efficacy. However, the CSRs of cases with leaks and fistulae and D ≤ 10 were 71.4% (5/7) in the SS-group and 100% (7/7) in the TG-group. Delayed leakages occurred in two cases in the SS-group (D ≤ 10 and acute leakage and D ≤ 10 and chronic fistula). These data suggest that the SS method sometimes fails to provide an acceptable clinical outcome despite the technical success, even if the defect size is small (D ≤ 10). These aspects of the SS method suggest that the TG is desirable for leaks and fistulae with defects of the entire layer.

| Parameters | Technical success rate | Clinical success rate | ||||

| SS (n = 14) | TG (n = 42) | P value1 | SS (n = 14) | TG (n = 42) | P value1 | |

| Indication | ||||||

| Refractory bleeding | 100 (7/7) | 81.8 (9/11) | 0.2315 | 85.7 (6/7) | 81.8 (9/11) | 0.8288 |

| Leak | 100 (2/2) | 92 (23/25) | 0.6776 | 50 (1/2) | 92 (23/25) | 0.0690 |

| Fistula | 100 (5/5) | 83.3 (5/6) | 0.3384 | 80 (4/5) | 83.3 (5/6) | 0.8865 |

| Location | ||||||

| Upper GI tract | 100 (8/8) | 85.3 (29/34) | 0.8725 | 75 (6/8) | 85.3 (29/34) | 0.8725 |

| Lower GI tract | 100 (6/6) | 100 (8/8) | 83.3 (5/6) | 100 (8/8) | 0.2308 | |

| Maximum defect size (D), mm | ||||||

| D ≤ 10 | 100 (14/14) | 100 (9/9) | 78.6 (11/14) | 100 (9/9) | 0.1364 | |

| 10 < D ≤ 20 | - | 88.9 (8/9) | - | - | 88.9 (8/9) | - |

| 20 < D | - | 83.3 (20/24) | - | - | 83.3 (20/24) | - |

| Duration since onset, % (n) | ||||||

| Immediate ≤ 1 d | 100 (3/3) | 95.5 (21/22) | 0.6994 | 100 (3/3) | 95.5 (21/22) | 0.6994 |

| 1 < Acute ≤ 7 d | 100 (3/3) | 87.5 (7/8) | 0.1247 | 66.7 (2/3) | 87.5 (7/8) | 0.1247 |

| Chronic > 7 d | 100 (8/8) | 75 (9/12) | 0.1250 | 75 (6/8) | 75 (9/12) | 1.0000 |

| Clinical success rate | ||||||

| Indications | Refractory bleeding (n = 18) | Leak (n = 27) | Fistula (n = 11) | |||

| Combined parameters | SS (n = 7) | TG (n = 11) | SS (n = 2) | TG (n = 25) | SS (n = 5) | TG (n = 6) |

| D ≤ 10, Immediate | 100% | 100% | - | 100% | - | - |

| D ≤ 10, Acute | 100% | - | 50% | 100% | - | - |

| D ≤ 10, Chronic | 66.7% | 100% | - | - | 80% | 100% |

| 10 < D ≤ 20, Immediate | - | 100% | - | 66.7% | - | - |

| 10 < D ≤ 20, Acute | - | 100% | - | 100% | - | - |

| 10 < D ≤ 20, Chronic | - | 100% | - | - | - | 100% |

| D > 20, Immediate | - | 100% | - | 100% | - | - |

| D > 20, Acute | - | - | - | 75% | - | - |

| D > 20, Chronic | - | 33.3% | - | - | - | 50% |

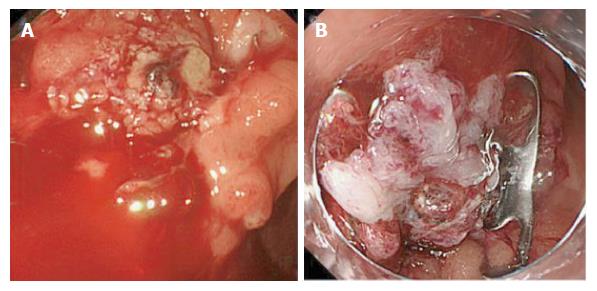

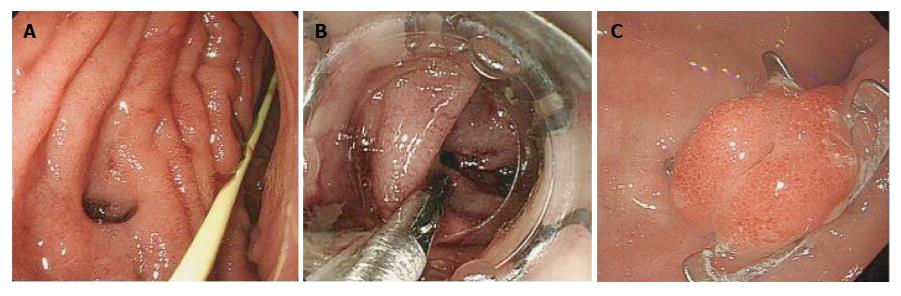

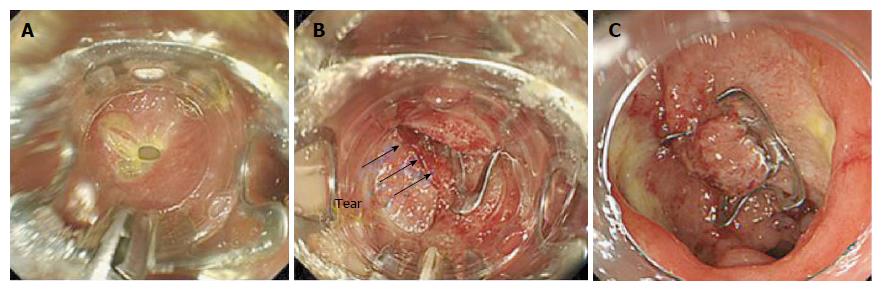

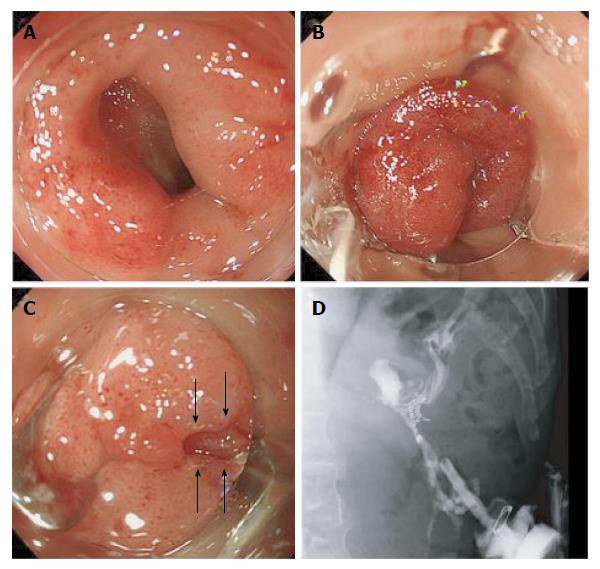

A representative success of SS in refractory bleeding is shown in Figure 3. In a failure case in the SS-group with D ≤ 10 and a chronic duration, conventional therapy-resistant ulcer bleeding that in the terminal ileum occurred during steroid treatment for myelodysplastic syndrome. Despite the successful closure of the defect with the SS method, additional surgery was needed because of re-bleeding that might have been caused by angiogenesis from the steroid treatment in specific circumstances (Table 7, case No. 1). The CSR of the TG-group among cases with D > 20 showed the lowest success rate, 33.3% (1/3). In these 2 failure cases of chronic, fibrotic ulcers with D > 20, technical success could not be achieved due to an inability to suck rigid tissues into the cap, even when using the TG (Table 7, case No. 2 and No. 3). Although the use of the Anchor might have been helpful[18], we did not introduce the device because of the risk of perforation by the bear claw of the device. Finally, these bleeds were managed with conventional therapies using hemostatic forceps. At the indication of a leak, the TG method provided good clinical outcomes for defects with D ≤ 10 and immediate duration during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP); an image of a representative case is shown in Figure 4. On the other hand, there were three clinical failure cases with leaks: one with SS with D ≤ 10 and an acute duration, one with the TG with 10 < D ≤ 20 and an immediate duration, and one with the TG with D > 20 and an acute duration. In the first case, an acute anastomotic leakage with D ≤ 10 after surgery for gastric cancer that was located in the esophageal-gastric junction was successfully closed using SS, but additional surgery was needed because of a delayed leakage (Table 7, case No. 4). In the second case, a large perforation of approximately 20 mm occurred during ERCP, and the TG was used to approximate the defect. The collapse of the intestine because of air leakage made technical success impossible, and this case required surgical repair (Table 7, case No. 5). In the third case, a delayed perforation with a 50-mm defect size occurred after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. The defect could not be closed with the TG because of a narrow lumen in the prepylorus and the large defect size. The misplacement of the OTSC on the exposed muscularis propria induced additional tears, which represents the only case of an OTSC complication in this study. Although the use of several hemoclips at the perforation site seemed to be effective, surgery was performed due to the re-appearance of free air in computed tomography (CT) images 3 d after endoscopic therapy (Table 7, case No. 6, shown as the only complication in Figure 5). Among the fistula cases, there were two clinical failures: one with SS with D ≤ 10 and a chronic duration and one with TG with 10 < D ≤ 20 and a chronic duration. The first case was an 8-mm gastric fistula that occurred after an interventional endoscopic ultrasound for a pseudo-pancreatic cyst (Table 7, case No. 7), which is shown in Figure 6. Although the fistula was successfully closed using SS, leakage occurred 2 wk after OTSC placement, which necessitated additional surgery. The other case was a large (22 mm in diameter) gastric tube-tracheal fistula that occurred after radiation for esophageal carcinoma. The fistula could not be treated with the TG and required surgery (Table 7, case No. 8). Details of these 8 clinical failure cases are summarized in Table 7.

| Indication | Max. defect size, mm | Cause, comorbidity | Location | Prior therapy | Duration since onset | Technical success | Technical or clinical failure factor | Additional therapy | Clinical outcome |

| Refractory bleeding | 8 | Ileal ulcer bleeding due to steroid treatment for myelodysplastic syndrome | Terminal ileum | EI (hemoclips and coagulation) | Chronic | Yes | Suspicion of angiogenesis due to steroid in particular circumstances | Elective surgery | Survival |

| Refractory bleeding | 20 | Peptic ulcer, Refractory neurogenic disease | Stomach (body) | EI (coagulation) | Chronic | No | Fibrotic tissue | Retry of EI | Survival |

| Refractory bleeding | 50 | Peptic ulcer, Advanced gallbladder carcinoma | Stomach (body) | EI (coagulation) | Chronic | No | Fibrotic tissue | Retry of EI | Survival |

| Leak | 7 | Anastomotic leakage after surgery for gastric cancer | Esophageal gastric junction | None | Acute | Yes | Leakage by mucosal suture (suspected) | Elective surgery | Survival |

| Leak | 21 | Perforation during ERCP | Duodenal 2nd portion | None | Immediate | No | Inability of platform | Emergency surgery | Survival |

| Leak | 50 | Delayed perforation after ESD | Stomach (prepyrolus) | None | Acute | No | Location with narrow lumen | Elective surgery | Survival |

| Fistula | 8 | Interventional EUS | Gastric (prepyrolus)- pseudopancreatic cyst | None | Chronic | Yes | Leakage by mucosal suture (suspected) | Elective surgery | Survival |

| Fistula | 22 | Radiation for esophageal carcinoma | Gastric tube-trachea | Bronchial embolization | Chronic | No | Fibrotic tissue | Elective surgery | Survival |

A newly developed endoscopic full-thickness suturing device, the OTSC system, has allowed for the endoscopic closure of conventional therapy-resistant GI defects. The efficacy of OTSC has been widely known since its introduction in 2009 in Western countries. However, there have been few studies that used large samples of more than fifty cases and a multicenter design.

Additionally, the type of suction method that should be applied to each target lesion based on the particular lesion characteristics remains unclear. Successful OTSC closure depends on the secure suction of the target lesion into the application cap. This success is closely related to the extent of tissue fibrosis in proportion to the duration from onset to OTSC placement, as previously described[14,15]. Therefore, an optimal strategy for choosing a suction method for the OTSC system is needed. This study is the first to clarify these issues by comparing the clinical data of SS to TG.

Compared to TG, SS has the advantage of rapid and convenient use with a system that is similar to endoscopic variceal band ligation (mean procedure time; SS 5.9 min vs TG 14.1 min, P < 0.05). Moreover, another merit of SS is its lower cost if accessory devices are not applied. A maximum defect size of 10 mm per clip can be completely closed with the SS method, considering the caliber of the application cap. If OTSC is not fired due to insufficient suction into the cap during SS method, TG assist can be an alternative choice to close the defect. Although no significant differences in TSR or CSR were observed between the two groups in this study, the CSR of the SS-group (78.6%, 11/14), despite its technical success (TSR, 100%, 14/14), tended to decrease compared to the TG-group (TSR, CSR; 88.1%, 37/42) due to delayed leakage. This finding indicates that the SS method might result in some clinical failures despite its technical success. Therefore, a secondary evaluation regarding each parameter or combined parameters for each indication was performed to better clarify the quality of each method. The CSR of the SS-group with D ≤ 10 and immediate or acute refractory bleeding was 100%, which suggested that SS was a better method than TG in terms of time efficacy. However, the CSRs of leaks and fistulae with D ≤ 10 were 71.4% (5/7) in the SS-group and 100% (7/7) in the TG-group. Delayed leakages occurred in two cases in the SS-group (D ≤ 10 and acute leakage and D ≤ 10 and chronic fistula). These interesting data suggest that the SS method might sometimes fail in full-thickness suturing and could result in mucosal suturing for the target tissue, even if the defect size is small. Moreover, OTSC system using TG assist after clinical failure of SS method is not applicable for the same defect, because it is difficult to remove endoscopically the deployed OTSC on the target lesion. In this situation, surgery will be the only suitable therapy as shown in Figure 2. Thus, the use of TG may be desirable for leaks and fistulae with defects of the entire layer.

The TG is commonly used for large defects, but details regarding defect sizes and indications are unknown. The CSR in the TG-group decreased as defect size and duration since onset increased (Table 5). In particular, the success rate in the TG-group was the lowest for defects with D > 20 and those that were chronic, which indicates the limitations of the TG for large defects with fibrosis. If the TG method fails in this condition, a retrial with the Anchor might be valuable. Further comparative studies that include the Anchor are needed to clarify its efficacy and limitations.

Currently, there are limited data from large sample sizes[15] and few comparative studies[16,17]. Specifically, clinical studies including more than 50 cases, as in the present study, are rare. Here, we summarized the overall CSR in human studies between 2011 and 2015 that involved a minimum of 2 wk of follow-up, and we included several important parameters (e.g., defect size, use of accessory devices) (Table 8)[19-26]. The mean rate of overall clinical success was 68.4% (range 53-90) (329/481 cases), which includes our results. Our data revealed a high rate of overall clinical success (84.5%). This finding may be why no significant differences in TSR or CSR were observed between the two groups in this study. Additionally, the proportion of fistulae and/or the defect size included in other studies may be associated with the OTSC success rate. According to a large sample of data, a defect type with fibrotic tissue, such as a fistula, is the most important predictor of OTSC failure[15]. Therefore, we evaluated the success rates of three types of indications separately (refractory bleeding, leaks, and fistulae). The mean rates of overall clinical success in refractory bleeding, leaks, and fistulae were 87.8%, (79/90 cases), 83.2% (109/131), and 53.0% (133/251), respectively.

| Ref. | Year | Country | Patients (n) | Overall clinical success rate, (success/ total) | Mean defect size (mm) | Described data of suction method | Complications, n (%) | ||||

| Refractory bleeding | Leaks and/or perforations | Fistula | Others | Total | |||||||

| Albert et al[20] | 2011 | Germany | 19 | 57.1 (4/7) | 87.5 (7/8) | 25 (1/4) | - | 63.2 | Unknown | Unknown | 0 |

| Surace et al[21] | 2011 | France, Monaco | 19 | - | - | 74 (14/19) | - | 73.7 | Unknown | Unknown | 1 (5) |

| Kirschniak et al[22] | 2011 | Germany | 50 | 92.6 (25/27) | 100 (11/11) | 37.5 (3/8) | 100 (4/4) | 86 | 6 | Unknown | 0 |

| Baron et al[19] | 2012 | United States | 45 | 100 (7/7) | 62.5 (5/8) | 67.9 (19/28) | 50 (1/2) | 71 | Unknown | TG: 8 cases AC: 17 cases | 2 (4.4) |

| Manta et al[23] | 2013 | Italy | 30 | 90 (27/30) | - | - | - | 90 | Unknown | Unknown | 0 |

| Haito-Chavez et al[15] | 2014 | International2 | 188 | - | Leaks 73.3 (22/30), 21 Perforations 90 (36/40), 81 | 42.9 (39/91), 171 | - | 60.2 | Leaks: 8 Perforations: 7 Fistula: 5 | Use of TG and/or AC, 50% (70/140 cases)3 | 0 |

| Law et al[24] | 2014 | United States | 47 | - | - | 53 (25/47) | - | 53 | Unknown | Unknown | 0 |

| Sulz et al[25] | 2014 | Switzerland | 21 | 100 (1/1) | 66.7 (4/6) | 63.6 (7/11) | 100 (3/3) | 71.4 | 8 | SS:4 100% (10/10) TG:100% (1/1) AC: 87.5% (7/8) TG + AC: 0% (0/1) | 0 |

| Mercky et al[26] | 2015 | France, Monaco | 30 | - | - | 53 (16/30) | - | 53 | 7.2 | SS: 17 procedures TG: 9 procedures AC: 5 procedures | 4 (13.3) |

| Our study | 2016 | Japan | 58 | 83.3 (15/18) | 85.7 (24/28) | 83.3 (10/12) | - | 84.5 | 19.6 | CSR SS4: 78.6% (11/14) TG: 88.1% (37/42) AC: 50% (1/2) | 1 (1.8) |

| Total | 507 | 87.8 (79/90) | 83.2 (109/131) | 53.0 (133/251) | 88.9 (8/9) | 68.4 (329/481) | 8/481 (1.66) | ||||

Similar to the overall mean rate of complications (1.66%, 8/481), there was only one case in which the misplacement of the OTSC to exposed muscularis propria induced additional tears in this study (1.8% complication rate). Although OTSCs have been demonstrated to be safe, a careful approach is needed to avoid OTSC placement on exposed muscularis propria, which can occur in a defect after endoscopic resection.

The OTSC system offers the strongest impact in regards to GI bleeding compared to other indications, as evidenced by the mean rate of overall clinical success of 87.8%, (79/90 cases), which is similar to the findings in our study (83.3%, 15/18). Therefore, an OTSC is a good device with which to achieve hemostasis in conventional therapy-resistant GI bleeding. However, as our 2 failure cases with D > 20 and chronic fibrotic ulcers revealed, OTSC usage may be limited in particular situations.

Perforations, deep defects with the risk of delayed perforations, and anastomotic leakages were included as leaks in this study. As the mean rate of overall clinical success and our CSR were 83.2% (range 62.5-100) (109/131) and 85.7% (24/28), respectively, the OTSC is valuable in avoiding emergency surgery for leaks.

Among all of the indications, the mean rate of overall clinical success for fistula was the lowest (53.0%, range 25-81.8, 133/251 cases). Similarly, recent studies have demonstrated a limited success rate of approximately 50%. Despite the introduction of the OTSC system, fistula closure appears to be a challenge. However, compared to other studies, our study delivered good outcomes with both technical (91.7%, 11/12 cases) and clinical success (83.3%, 10/12 cases). Law et al[24] reported that nearly 50% of patients with endoscopic and radiologic evidence of fistula closure at completion of the index procedure went on to require additional interventions in the subsequent days and months due to fistula recurrence. Accordingly, we recommend the use of sufficient suction into the cap with the aggressive use of accessory devices for the successful long-term closure of fistulae. In the future, the issue of managing refractory fistulae may be overcome by utilizing one or more of the following modalities: the injection of tissue sealants[27], stent placement[28,29], and newly developed endoscopic suturing devices[4,5,30].

The main limitation of this study is its retrospective design. Additionally, the selection of the suction method depended on the operator's discretion, so patient inclusion criteria were subjective. Therefore, the Anchor device was applicable only for a small number of cases in our experience.

This study has several strengths. Compared to related studies, it is a relatively large, multicenter study. Additionally, this study is the first to investigate which type of suction method is appropriate for particular situations according to the following characteristics: defect size, duration since onset, and indication.

In conclusion, the OTSC system is a safe and effective therapeutic option for the treatment of GI defects. The individualized choice of the suction method in the OTSC system is the most important factor for OTSC success. Thus, OTSCs can serve as reliable and productive devices for GI refractory diseases when the size of the defect, the duration since onset and the indication are considered.

Although the efficacy of over-the-scope clip (OTSC) for gastrointestinal (GI) defects involving GI refractory bleeding, leakages, and fistulae had been described, there are few data using large samples over fifty cases. Additionally, a successful key of OTSC closure depends on the secure suction into the application cap of the target lesion. There are three suction methods: simple suction (SS) and two accessory devices, referred to as the Twin Grasper (TG) and the tissue anchoring device, the Anchor. However, an optimal strategy for selecting a suction method, which is a critical factor of OTSC success, remains unclear.

This study demonstrates clinical outcomes of OTSCs using large samples and proposes a directional strategy for choosing a suction method into the application cap of the OTSC system.

Compared to related studies, this is a multicenter study with a large number of cases. Additionally, this study is the first to investigate which type of suction method is appropriate for particular situations according to the following characteristics: defect size, duration since onset, and indication. Although the SS method is indicated for cases with a maximum defect size ≤ 10 mm and immediate or acute refractory bleeding in terms of time efficacy, SS sometimes fails in full-thickness suturing. Thus, the use of TG may be desirable for leaks and fistulae with defects of the entire layer.

This study emphasizes that OTSC system is a safe and effective therapeutic option for GI defects. Moreover, individualized selection of the suction method based on particular clinical conditions may contribute to the improvement of OTSC success.

OTSC: A newly developed endoscopic full-thickness suturing device applicable for refractory bleeding, perforations, anastomotic leakage, and fistulae. Suction method: a method to suck the target lesion into the application cap, which is a critical factor of OTSC success among OTSC procedures.

The authors reported a multicenter retrospective study analyzing the role of the OTSCs for GI defects based on the suction method. The authors suggested that TG is desirable for leaks and fistulae with defects of the entire layer. However, further prospective studies by comparing suction methods are needed to clarify the type of suction method that should be applied to each target lesion based on the particular lesion characteristics.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Gurbulak B, Perez-Cuadrado-Robles E S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu WX

| 1. | Schecter WP, Hirshberg A, Chang DS, Harris HW, Napolitano LM, Wexner SD, Dudrick SJ. Enteric fistulas: principles of management. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:484-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gotoda T, Yamamoto H, Soetikno RM. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:929-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 485] [Cited by in RCA: 507] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mori H, Kobara H, Kobayashi M, Muramatsu A, Nomura T, Hagiike M, Izuishi K, Suzuki Y, Masaki T. Establishment of pure NOTES procedure using a conventional flexible endoscope: review of six cases of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Endoscopy. 2011;43:631-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jirapinyo P, Watson RR, Thompson CC. Use of a novel endoscopic suturing device to treat recalcitrant marginal ulceration (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:435-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mori H, Kobara H, Kazi R, Fujihara S, Nishiyama N, Masaki T. Balloon-armed mechanical counter traction and double-armed bar suturing systems for pure endoscopic full-thickness resection. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:278-280.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | von Renteln D, Denzer UW, Schachschal G, Anders M, Groth S, Rösch T. Endoscopic closure of GI fistulae by using an over-the-scope clip (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1289-1296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fujihara S, Mori H, Kobara H, Nishiyama N, Ayaki M, Nakatsu T, Masaki T. Use of an over-the-scope clip and a colonoscope for complete hemostasis of a duodenal diverticular bleed. Endoscopy. 2015;47 Suppl 1 UCTN:E236-E237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kobara H, Mori H, Rafiq K, Fujihara S, Nishiyama N, Kato K, Oryu M, Tani J, Miyoshi H, Masaki T. Successful endoscopic treatment of Boerhaave syndrome using an over-the-scope clip. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E82-E83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mori H, Kobara H, Nishiyama N, Fujihara S, Matsunaga T, Chiyo T, Masaki T. Rescue therapy with over-the-scope clip closure for a large postoperative colonic leak. Endoscopy. 2015;47 Suppl 1 UCTN:E115-E116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nishiyama N, Mori H, Rafiq K, Kobara H, Fujihara S, Kobayashi M, Masaki T. Over-the-scope clip system is effective for the closure of post-endoscopic submucosal dissection ulcer, especially at the greater curvature. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E130-E131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Manta R, Manno M, Bertani H, Barbera C, Pigò F, Mirante V, Longinotti E, Bassotti G, Conigliaro R. Endoscopic treatment of gastrointestinal fistulas using an over-the-scope clip (OTSC) device: case series from a tertiary referral center. Endoscopy. 2011;43:545-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kothari TH, Haber G, Sonpal N, Karanth N. The over-the-scope clip system--a novel technique for gastrocutaneous fistula closure: the first North American experience. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:193-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dişibeyaz S, Köksal AŞ, Parlak E, Torun S, Şaşmaz N. Endoscopic closure of gastrointestinal defects with an over-the-scope clip device. A case series and review of the literature. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:614-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nishiyama N, Mori H, Kobara H, Rafiq K, Fujihara S, Kobayashi M, Oryu M, Masaki T. Efficacy and safety of over-the-scope clip: including complications after endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2752-2760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Haito-Chavez Y, Law JK, Kratt T, Arezzo A, Verra M, Morino M, Sharaiha RZ, Poley JW, Kahaleh M, Thompson CC. International multicenter experience with an over-the-scope clipping device for endoscopic management of GI defects (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:610-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | von Renteln D, Vassiliou MC, Rothstein RI. Randomized controlled trial comparing endoscopic clips and over-the-scope clips for closure of natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery gastrotomies. Endoscopy. 2009;41:1056-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Martínek J, Ryska O, Tuckova I, Filípková T, Doležel R, Juhas S, Motlík J, Zavoral M, Ryska M. Comparing over-the-scope clip versus endoloop and clips (KING closure) for access site closure: a randomized experimental study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1203-1210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kirschniak A, Kratt T, Stüker D, Braun A, Schurr MO, Königsrainer A. A new endoscopic over-the-scope clip system for treatment of lesions and bleeding in the GI tract: first clinical experiences. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:162-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Baron TH, Song LM, Ross A, Tokar JL, Irani S, Kozarek RA. Use of an over-the-scope clipping device: multicenter retrospective results of the first U.S. experience (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:202-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Albert JG, Friedrich-Rust M, Woeste G, Strey C, Bechstein WO, Zeuzem S, Sarrazin C. Benefit of a clipping device in use in intestinal bleeding and intestinal leakage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:389-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Surace M, Mercky P, Demarquay JF, Gonzalez JM, Dumas R, Ah-Soune P, Vitton V, Grimaud J, Barthet M. Endoscopic management of GI fistulae with the over-the-scope clip system (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1416-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kirschniak A, Subotova N, Zieker D, Königsrainer A, Kratt T. The Over-The-Scope Clip (OTSC) for the treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding, perforations, and fistulas. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2901-2905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Manta R, Galloro G, Mangiavillano B, Conigliaro R, Pasquale L, Arezzo A, Masci E, Bassotti G, Frazzoni M. Over-the-scope clip (OTSC) represents an effective endoscopic treatment for acute GI bleeding after failure of conventional techniques. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3162-3164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Law R, Wong Kee Song LM, Irani S, Baron TH. Immediate technical and delayed clinical outcome of fistula closure using an over-the-scope clip device. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:1781-1786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sulz MC, Bertolini R, Frei R, Semadeni GM, Borovicka J, Meyenberger C. Multipurpose use of the over-the-scope-clip system ("Bear claw") in the gastrointestinal tract: Swiss experience in a tertiary center. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16287-16292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mercky P, Gonzalez JM, Aimore Bonin E, Emungania O, Brunet J, Grimaud JC, Barthet M. Usefulness of over-the-scope clipping system for closing digestive fistulas. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:18-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Huang CS, Hess DT, Lichtenstein DR. Successful endoscopic management of postoperative GI fistula with fibrin glue injection: Report of two cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:460-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rao AS, LeRoy AJ, Bonin EA, Sweetser SR, Baron TH. Novel technique for placement of overlapping self-expandable metal stents to close a massive pancreatitis-induced duodenal fistula. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 2 UCTN:E163-E164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lamazza A, Fiori E, Sterpetti AV. Endoscopic placement of self-expandable metal stents for treatment of rectovaginal fistulas after colorectal resection for cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:1025-1027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kantsevoy SV, Bitner M, Mitrakov AA, Thuluvath PJ. Endoscopic suturing closure of large mucosal defects after endoscopic submucosal dissection is technically feasible, fast, and eliminates the need for hospitalization (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:503-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |