Published online Feb 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i8.1507

Peer-review started: November 4, 2016

First decision: December 2, 2016

Revised: December 15, 2016

Accepted: January 4, 2017

Article in press: January 4, 2017

Published online: February 28, 2017

Processing time: 115 Days and 23.6 Hours

Following an increase in the use of the GIA stapler for treating a pancreatic stump, more techniques to prevent postoperative pancreatic juice leakage have been required. We describe one successful case using our new technique of invaginating the cut end of the pancreas into the stomach to prevent a pancreatic fistula (PF) from occurring. A 50-year-old woman with pancreatic cancer in the tail of the pancreas underwent distal pancreatectomy, causing a grade A PF. We resected the distal pancreas without additional reinforcement to invaginate the stump into the gastric posterior wall with single layer anastomosis using a 3-0 absorbable suture. The drain tubes were removed on the third postoperative day. Although a grade A PF was noted, the patient was discharged on foot on the eleventh postoperative day. Our technique may be a suitable method for patients with a pancreatic body and tail tumor.

Core tip: More techniques for preventing postoperative pancreatic juice leakage have been required since the use of GIA stapler has increased. We describe one successful case wherein our new technique of invaginating the cut end of the pancreas into the stomach was used to prevent a pancreatic fistula (PF) from occurring. A 50-year-old woman with pancreatic cancer in the tail of the pancreas underwent distal pancreatectomy. Although a grade A PF was noted, the patient was discharged on foot on the eleventh postoperative day. Our technique may be a suitable method for patients with a pancreatic body and tail tumor.

- Citation: Katsura N, Kawai Y, Gomi T, Okumura K, Hoashi T, Fukuda S, Takebayashi K, Shimizu K, Satoh M. Preventing pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy: An invagination method. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(8): 1507-1512

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i8/1507.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i8.1507

Historically, it has been recognized that post-pancreatectomy complications can be severe[1]. Generally, pancreaticoduodenectomy or distal pancreatectomy will cause a pancreatic fistula (PF) to some extent, and it has been said that complete prevention of PF after pancreatectomy is impossible. A PF can cause an intra-abdominal abscess due to an activated bacterial infection, which can result in sepsis, hemorrhage[2-5], and delayed gastric emptying[6]. To prevent these complications, various methods have been reported; however, to date, none of them has become a standard procedure[7]. Here, we describe our experience invaginating the pancreatic stump into the stomach after distal pancreatectomy with an excellent result.

A 50-year-old woman had a hard navel mass. She regularly visited the Department of Internal Medicine at our hospital for the treatment of diabetes. In August 2011, she presented to the Department of Dermatology with a main complaint of an umbilical mass; however, she was sent to the Surgical Department because of the diagnosis of an umbilical lesion located deep in the abdomen. The hard mass, which was the size of a thumb, was palpable at her navel. She did not feel any pain.

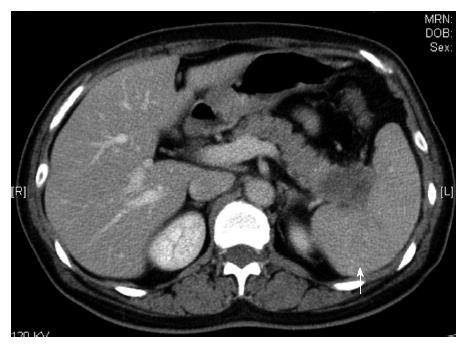

An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed the enhanced tumor; it was 2 cm in diameter and located in the pancreatic tail (Figure 1). The contrasting effect was poor compared to normal tissue, which was a finding suggestive of pancreatic cancer. The para-aortic lymph node was not swollen; however, low, enhanced foci were scattered in the spleen, which was a finding suggestive of metastasis.

The fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan showed swelling in the pancreatic tail with abnormal accumulation (Figure 2). This contrasting pattern along with the CT findings suggested pancreatic cancer. Accumulation in the spleen was noted, so we were unable to rule out the possibility of invasion. There was a small granular shadow with slight accumulation suggestive of lymph node metastases.

Skin thickening and abnormal accumulation in the umbilical region were also noted. Consecutive accumulation was not observed in the peritoneum, which was suggestive of local inflammation, not dissemination. No other abnormality was found.

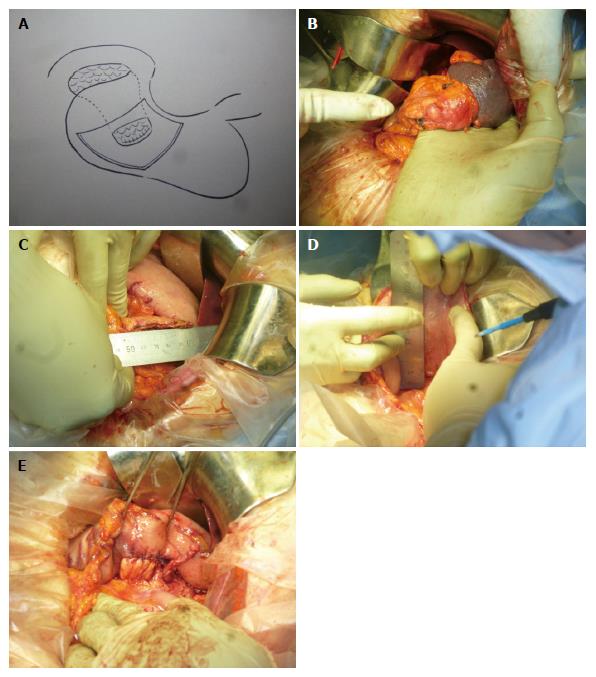

The patient was placed in a supine position for the operation. First, we used Kocher mobilization at the front part of the inferior vena cava, moving toward the anterior surface of left renal vein to back side of the superior mesenteric artery. We confirmed no para-aortic lymph node swelling. The greater omentum was resected from the spleen to the pancreas, transverse colon, and splenic flexure. The inferior mesenteric vein was set aside. The adhesion between the stomach and pancreas was opened. In addition, the posterior gastric vein was separated, and the coronary vein was preserved. The spleen was separated from the retroperitoneum. Next, the left adrenal gland was resected from the pancreas and preserved intact. The pancreas was cut at the anterior of the superior mesenteric artery, and the pancreatic tail, including the tumor, was extracted. The stump and tumor were quick frozen for pathological examination; the pancreatic duct stump was ligated with 5-0 prolene sutures. The patient was diagnosed as having pancreatic cancer, and the pancreatic stump was not malignant. The gastric posterior wall was transected to approximately 80% of the stump width. Single layer anastomosis was performed with 3-0 absorbable sutures (Figure 3A-E). One soft drain was placed under the left diaphragm and the hiatus of Winslow after washing with 2000 mL of saline. The left side of the greater omentum was used to cover the stomach-pancreas anastomotic region. The operative time was 211 min, and the blood loss was 162 mL.

The invasive ductal carcinoma of the pancreatic tail, scirrhous, nodular, Infγ , ly0, v1, ne3, mpd(-), s(+), rp(-), PVsp(+), A(-), pcm(-), mdpm(-), and M1(umbilicus) carcinoma, formed the mass (30 × 25 mm) and showed serosa exposure and progress to the outer membrane of the spleen. This mass was a tub1(> tub2)-based tubular, scirrhous adenocarcinoma. It was accompanied by high neurologic and splenic vein invasion. Each excised stump was negative for malignancy.

Cytology of ascites showed that the umbilical region mass, the invasive ductal carcinoma, was a class V adenocarcinoma.

The drain was removed after the drain fluid amylase level decreased to 190 IU/L on day 3 from 1595 IU/L on day 1. The patient was discharged without any problems on postoperative day 11.

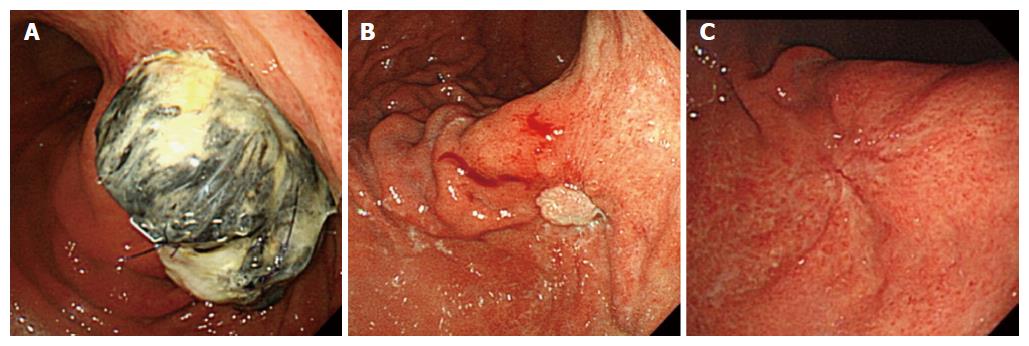

We have followed the patient’s pancreatic stump in the stomach postoperatively for 1 year using a gastric fiber scope. After 1 wk, the stump was massive; however, after 3 mo, the gastric mucosa covered almost the entire stump end. After 1 year, we could not detect the stump in the stomach (Figure 4A-C).

Ligation of the main pancreatic duct with a fish-mouth-shaped closure of the cut end has long been considered a standard technique for distal pancreatectomy[7]. However, it has generally been said that the probability of PF occurrence is in the range of 32% to 57%[8-12]. This can cause an intra-abdominal abscess with lethal results. When an intra-abdominal hemorrhage occurs, there is a 30% to 50% possibility of death; therefore, it is important to prevent PF after distal pancreatectomy. A recently published systemic review appraised all available surgical alternatives for handling the pancreatic remnant after distal pancreatectomy[1]. However, in many cases, the improved surgical techniques could not significantly reduce the incidence of PF[13].

Balcom et al[14] investigated 190 distal pancreatectomies over a 10-year period from April 1990 to October 2000 at the Massachusetts General Hospital. They divided the cases into three periods (from September 1998 to October 2000, from July 1995 to August 1998, and from April 1990 to June 1995), and the incidence rates of PF during each period were 12%, 17%, and 14%, respectively. In other words, the incidence of PF did not decrease from 1990 to 2000. As a result, several studies have tried to identify improved methods of preventing PF after distal pancreatectomy. We can classify these methods into the following categories: (1) operation apparatus development; (2) ingenuity in drainage; (3) choice of drugs; and (4) development of operative techniques.

Several apparatuses have been investigated: the supersonic wave surgery aspirator (cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator), supersonic wave solidification incision device, and automatic suture device. The frequencies of PF with these aforementioned apparatuses have been reported as 4%, 8%, and 5.5 to 34%, respectively[15,16]. None of the reported apparatuses has completely prevented PF.

There are few studies on the predictive value of amylase in drains[17]. Regarding the contrivance of the drainage method, Molinari et al[18] measured serum amylase levels in drainage fluid postoperatively. They reported that it is possible to identify the risk of PF formation and development of complications using an amylase level of > 5000 U/L on postoperative day 1. They also reported that patients may benefit from lengthening the time of intensive postoperative therapy. When a PF was confirmed or suspected, contrast examination of the drain was performed, and they determined the most effective drainage route by studying the flow of contrast media and performing enforced washing of saline (2000 mL/d). Continuous washing was performed for 1-3 wk depending on the clinical situation and amylase level of the drain.

The use of different drugs in an attempt to prevent PF has been reported. Konishi et al[19] reported the use of prolamine emulsion, which is regularly used to treat kidney tumors; it was injected into the main pancreatic duct. According to the authors, no patient developed a PF among the 51 cases of distal pancreatectomy. Suzuki et al[7] also reported the use of fibrin glue for sealing the pancreatic stump to prevent PF following distal pancreatectomy. They reported that 15.4% of patients in the fibrin glue sealing group and 40.0% of those in the control group were diagnosed as having a PF after distal pancreatectomy. However, they stated the following concerns: the injection of drugs may destroy the lobular structure of the parenchyma and cause atrophic fibrosis of the exocrine glands.

When it comes to the development of operative maneuvers, Kuroki et al[20] reported a trial of 20 patients in whom the pancreatic stump was covered with the gastric wall, and they compared these patients to 33 patients in whom the conventional method was performed. Using their new technique, only one case (5.0%) of PF occurred. Conversely, 12 cases (36.4%) of PF occurred in patients treated with the conventional method. Additionally, they discussed the hardness of the pancreas. Namely, PF can easily occur in a soft pancreas, so the hardness of the pancreas should be considered when comparing the incidence of PF between methods. Lillemoe et al[21] reported their method of covering the pancreatic stump with a ligament from the liver, and they asserted that it is easy to use.

Authors of these previous reports declared the superiority of their method; however, we do not believe that there have been enough cases to determine which method is best. These different techniques reflect the clinical heterogeneity in this field[1]. The impact of these techniques is difficult to interpret owing to small sample sizes, non-randomized study designs, and inconsistent study populations and fistula definitions.

Therefore, we developed our new method of invaginating the pancreatic stump into the stomach. Using this method, all leakage from the pancreatic stump flows into the stomach, so the results would not be dependent on the stiffness of the pancreas. This procedure does not require high-level techniques, and it only takes approximately 20 min to complete. The predicted disadvantages of this method include the following: (1) delayed gastric emptying may occur due to deformity of the stomach after fixation of the pancreas; (2) if a major leakage occurred from the gastropancreatic anastomosis, very severe complications would follow; and (3) if a future operation of the stomach is needed, it would be difficult to perform. However, this technique has been used for several years for pancreatoduodenectomy, with no major problems[22,23]. However, another limitation is that this procedure would not be beneficial in all cases. If the pancreatic tumor would have been on the left side of the portal vein and if the pancreatic resection line could not be moved to the left side of the portal vein, then we would not have been able to perform the invagination safely. In our case, if we had diagnosed the umbilical tumor as a metastasis of pancreatic cancer before the operation, pancreatectomy would not have been indicated. However, preoperative FDG-PET findings suggested that an inflammatory change had occurred, and we did not detect other metastases. We aimed to perform curative surgery and hoped to administer chemotherapy early. For these reasons, we needed to prevent PF as much as possible. Our patient was discharged on the eleventh day postoperatively and has not had any problems to date. We believe that our new method can be an effective procedure in some cases with distal pancreatectomy to prevent PF. We will continue to perform our method and collect data to examine its adequacy.

In conclusions, we obtained an excellent result in distal pancreatectomy invaginating the pancreatic stump into the stomach. Our new method may effectively prevent PF.

Editorial support, in the form of medical writing based on authors’ detailed directions, collating author comments, copyediting, and fact checking provided by Cactus Communications.

A 50-year-old woman with a palpable umbilical mass at her navel.

A 2-cm-diameter tumor located in the pancreatic tail, along with low, enhanced foci scattered in the spleen. These findings suggested that the pancreatic cancer had already metastasized.

The abdominal computed tomography scan showed a 2-cm-diameter tumor located in the pancreatic tail. The para-aortic lymph node was not swollen; however, low, enhanced foci were scattered in the spleen. The fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography scan showed swelling in the pancreatic tail with abnormal accumulation.

Cytology of ascites showed that the umbilical region mass, the invasive ductal carcinoma, was a class V adenocarcinoma.

The distal pancreas was resected without additional reinforcement to invaginate the stump into the gastric posterior wall with single layer anastomosis using a 3-0 absorbable suture.

Ligation of the main pancreatic duct with a fish-mouth-shaped closure of the cut end has long been considered a standard technique for distal pancreatectomy. However, the probability of pancreatic fistula (PF) occurrence ranges from 32% to 57%.

Pancreatectomy is performed to excise pancreatic tumors. This resection commonly results in a PF, which can further result in major complications.

There is a high probability of PF occurrence after pancreatectomy. Here, we describe the technique of invaginating the pancreatic stump into the stomach. This method may effectively prevent PF.

The authors describe a new innovative approach for preventing postoperative PF.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Aosasa S, Okamoto H, Sharma SS S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Knaebel HP, Diener MK, Wente MN, Büchler MW, Seiler CM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of technique for closure of the pancreatic remnant after distal pancreatectomy. Br J Surg. 2005;92:539-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zinner MJ, Baker RR, Cameron JL. Pancreatic cutaneous fistulas. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1974;138:710-712. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Fitzgibbons TJ, Yellin AE, Maruyama MM, Donovan AJ. Management of the transected pancreas following distal pancreatectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1982;154:225-231. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Papachristou DN, Fortner JG. Pancreatic fistula complicating pancreatectomy for malignant disease. Br J Surg. 1981;68:238-240. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Traverso LW. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2007;142:761-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1771] [Cited by in RCA: 2331] [Article Influence: 129.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Suzuki Y, Kuroda Y, Morita A, Fujino Y, Tanioka Y, Kawamura T, Saitoh Y. Fibrin glue sealing for the prevention of pancreatic fistulas following distal pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 1995;130:952-955. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Kleeff J, Diener MK, Z’graggen K, Hinz U, Wagner M, Bachmann J, Zehetner J, Müller MW, Friess H, Büchler MW. Distal pancreatectomy: risk factors for surgical failure in 302 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2007;245:573-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sierzega M, Niekowal B, Kulig J, Popiela T. Nutritional status affects the rate of pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy: a multivariate analysis of 132 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:52-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fahy BN, Frey CF, Ho HS, Beckett L, Bold RJ. Morbidity, mortality, and technical factors of distal pancreatectomy. Am J Surg. 2002;183:237-241. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Hutchins RR, Hart RS, Pacifico M, Bradley NJ, Williamson RC. Long-term results of distal pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis in 90 patients. Ann Surg. 2002;236:612-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rodríguez JR, Germes SS, Pandharipande PV, Gazelle GS, Thayer SP, Warshaw AL, Fernández-del Castillo C. Implications and cost of pancreatic leak following distal pancreatic resection. Arch Surg. 2006;141:361-365; discussion 366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fernández-del Castillo C, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL. Standards for pancreatic resection in the 1990s. Arch Surg. 1995;130:295-299; discussion 299-300. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Balcom JH, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL, Chang Y, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Ten-year experience with 733 pancreatic resections: changing indications, older patients, and decreasing length of hospitalization. Arch Surg. 2001;136:391-398. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Suzuki Y, Fujino Y, Tanioka Y, Hori Y, Ueda T, Takeyama Y, Tominaga M, Ku Y, Yamamoto YM, Kuroda Y. Randomized clinical trial of ultrasonic dissector or conventional division in distal pancreatectomy for non-fibrotic pancreas. Br J Surg. 1999;86:608-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sugo H, Mikami Y, Matsumoto F, Tsumura H, Watanabe Y, Futagawa S. Comparison of ultrasonically activated scalpel versus conventional division for the pancreas in distal pancreatectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8:349-352. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Yamaguchi M, Nakano H, Midorikawa T, Yoshizawa Y, Sanada Y, Kumada K. Prediction of pancreatic fistula by amylase levels of drainage fluid on the first day after pancreatectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1155-1158. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Molinari E, Bassi C, Salvia R, Butturini G, Crippa S, Talamini G, Falconi M, Pederzoli P. Amylase value in drains after pancreatic resection as predictive factor of postoperative pancreatic fistula: results of a prospective study in 137 patients. Ann Surg. 2007;246:281-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Konishi T, Hiraishi M, Kubota K, Bandai Y, Makuuchi M, Idezuki Y. Segmental occlusion of the pancreatic duct with prolamine to prevent fistula formation after distal pancreatectomy. Ann Surg. 1995;221:165-170. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Kuroki T, Tajima Y, Tsuneoka N, Adachi T, Kanematsu T. Gastric wall-covering method prevents pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:877-880. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Lillemoe KD. Omental roll-up technique decreases pancreatic fistula--or does it? Arch Surg. 2012;147:150-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mason GR. Pancreatogastrostomy as reconstruction for pancreatoduodenectomy: review. World J Surg. 1999;23:221-226. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Murakami Y, Uemura K, Hayashidani Y, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Nakagawa N, Ohge H, Sueda T. No mortality after 150 consecutive pancreatoduodenctomies with duct-to-mucosa pancreaticogastrostomy. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:205-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |