Published online Feb 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i8.1397

Peer-review started: November 28, 2016

First decision: December 19, 2016

Revised: December 31, 2016

Accepted: January 11, 2017

Article in press: January 11, 2017

Published online: February 28, 2017

Processing time: 90 Days and 22.1 Hours

To analyzed the correlation between smoking status and surgical outcomes in patients with non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma (NBNC-HCC), and we investigated the patients’ clinicopathological characteristics according to smoking status.

We retrospectively analyzed the consecutive cases of 83 NBNC-HCC patients who underwent curative surgical treatment for the primary lesion at Saga University Hospital between 1984 and December 2012. We collected information about possibly carcinogenic factors such as alcohol abuse, diabetes mellitus, obesity and smoking habit from medical records. Smoking habits were subcategorized as never, ex- and current smoker at the time of surgery. The diagnosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) was based on both clinical information and pathological confirmation.

Alcohol abuse, diabetes mellitus, obesity and NASH had no significant effect on the surgical outcomes. Current smoking status was strongly correlated with both overall survival (P = 0.0058) and disease-specific survival (P = 0.0105) by multivariate analyses. Subset analyses revealed that the current smokers were significantly younger at the time of surgery (P = 0.0002) and more likely to abuse alcohol (P = 0.0188) and to have multiple tumors (P = 0.023).

Current smoking habit at the time of surgical treatment is a risk factor for poor long-term survival in NBNC-HCC patients. Current smokers tend to have multiple HCCs at a younger age than other patients.

Core tip: We retrospectively analyzed the surgical outcomes and clinicopathological characteristics according to smoking habits in consecutive 83 cases with non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma (NBNC-HCC) patients who underwent curative surgical treatment for the primary lesion. Current smoking status was strongly correlated with both overall survival and disease-specific survival by multivariate analyses. Subset analyses revealed that current smokers tended to have multiple HCCs at a younger age than other patients. To our knowledge, this is the first report regarding surgical outcomes of NBNC-HCC patients in relation to their smoking status.

- Citation: Kai K, Koga H, Aishima S, Kawaguchi A, Yamaji K, Ide T, Ueda J, Noshiro H. Impact of smoking habit on surgical outcomes in non-B non-C patients with curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(8): 1397-1405

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i8/1397.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i8.1397

Infections with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are well known risk factors for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). As more than 90% of countries around the world have now introduced the HBV vaccine into their national infant immunization schedules, the incidence of HBV-related HCC has been decreasing dramatically[1]. The development of antivirus therapy can also reduce the incidence of HCV-related HCC[2]. The number of HCC patients who are negative for both hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis C antibody (HCVAb), i.e., those who have so-called “non-B non-C (NBNC) HCC” has rapidly increased in recent years. NBNC HCC patients were reported to account for 24.1% of all HCC patients in a 2010 Japanese survey[3]. It is thus very important, toward the prevention of HCC, to establish all of the etiologies of NBNC-HCC and to devise countermeasures for it.

The known etiologies of NBNC-HCC are alcoholic liver disease (ALD)[4], non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)[5,6], hemochromatosis[7], and Budd-Chiari syndrome[8]; other known etiologies include primary biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis, metabolic disease, congestive disease, parasitic disease and unknown etiology[9]. Emerging epidemiologic data suggest that cigarette smoking may increase the risk of developing HCC[10-12], but a smoking habit is generally less recognized as a risk factor of developing HCC compared to other etiologies such as ALD and NASH/NAFLD.

Surgery is one of the most important therapeutic measures for HCC. The correlations between surgical outcomes and each etiology of HCC are very important because knowing these correlations will provide the motivation and strategies for the prevention of each specific etiology. The clinicopathological characteristics and surgical outcomes of patients with HBV-HCC and HCV-HCC have been well investigated[13-15]. There are also many studies comparing the surgical outcomes or clinicopathological characteristics of patients with NBNC-HCC and those with viral-associated HCC or between each etiology of NBNC-HCC[16-29]. However, no study has addressed the impact of smoking habit on surgical outcomes or clinicopathological characteristics according to smoking habits in patients with NBNC-HCC, to our knowledge.

In the present study we analyzed the correlation between smoking status and surgical outcomes in patients with NBNC-HCC, and we investigated the patients’ clinicopathological characteristics according to smoking status.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at Saga University (approval no. 28-23). The initial enrollees in the study were 477 consecutive patients with HCC who underwent curative surgical treatment for the primary lesion at Saga University Hospital between 1984 and December 2012. Of these patients, we retrospectively examined the cases of the 83 patients who were both non-B (HBsAg-negative) and non-C (HCVAb-negative) in serological tests. One patient with Budd-Chiari syndrome and another patient with Dubin-Johnson syndrome were included. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for the use of their clinical information.

Alcohol abuse was defined as a daily ethanol intake > 40 g for men and > 20 g for women. Obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) > 25 kg/m2 in both genders. Smoking status was categorized as never smoker, ex-smoker and current smoker at the time of surgery. A current smoker was defined as an individual who regularly smoked and continued to smoke within 1 year prior to the surgery. An ex-smoker was defined as an individual who quit smoking at least 1 year before his or her surgery[30]. Only patients who were clinically diagnosed as having diabetes mellitus were categorized as being in the present diabetes mellitus group. All of this information was collected from medical records.

The histopathological diagnosis and classification were performed by two pathologists (Kai K and Aishima S). The degree of fibrosis in noncancerous liver tissues was assessed according to the new Inuyama classification system which is widely used in Japan, as follows: F0, no fibrosis; F1, portal fibrosis widening; F2, portal fibrosis widening with bridging fibrosis; F3, bridging fibrosis plus lobular distortion; and F4, liver cirrhosis[31]. In one case the fibrosis could not be assessed because of an insufficiency of noncancerous liver tissue. The diagnoses of NASH were based on both clinical information and pathological confirmation.

We used JMP ver. 12.2 software and SAS software ver. 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States) for the statistical analyses. The comparisons of pairs of groups were performed using Student’s t-test, the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Disease-free survival (DFS) was determined as the length of time after surgery that the patient survived without new lesions of HCC. Overall survival (OS) was determined from the time of surgery to the time of death or the most recent follow-up. Disease-specific survival (DSS) was determined from the time of surgery to the time of cancer-related death or most recent follow-up.

Cox proportional hazards modeling was applied for uni- and multivariate analyses. The purpose of the multivariate analysis was to adjust potential covariates for the comparison of smoking status; then, age, gender, portal vein invasion, T factor and multiple tumors were always kept in the model and others were selected by the stepwise procedure with the P value threshold of 0.2. Postoperative survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences in survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were supervised by the statistician co-author (Kawaguchi A).

The clinicopathological features of the 83 cases of NBNC-HCC are summarized in Table 1. The patients were 66 men and 17 women with a mean age at the time of surgery of 66.4 years. Nineteen patients (22.9%) were etiologically categorized into the alcohol abuse group; 29 patients (34.9%) had diabetes mellitus, and 26 patients (31.3%) were judged to be obese. Ten patients (12.2%) were pathologically confirmed as having NASH. Thirty-six patients (43.4%) were categorized into the never-smoker group and 23 (27.7%) into the ex-smoker group and the remaining 24 patients (28.9%) were currently smoking at the time of their surgery. The smoking cessation periods of the ex-smokers were as follows: 1-5 years, two patients; 5-10 years, four patients; and > 10 years, 17 patients.

| Characteristic | n (%) | |

| Age, yr (mean ± SD) | 66.4 ± 11.6 | |

| Gender | Male | 66 (79.5) |

| Female | 17 (20.5) | |

| Alcohol abuse | (+) | 19 (22.9) |

| (-) | 64 (77.1) | |

| Smoking habit | Never | 36 (43.4) |

| Ex | 23 (27.7) | |

| Current | 24 (28.9) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | (+) | 29 (34.9) |

| (-) | 54 (65.1) | |

| Obesity | (+) | 26 (31.3) |

| (-) | 57 (68.7) | |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 22.8 ± 4.50 | |

| Tumor size (mean ± SD mm) | 65.2 ± 41.4 | |

| Solitary/Multiple | Solitary | 52 (62.7) |

| Multiple | 31 (37.3) | |

| Vp | (+) | 32 (38.6) |

| (-) | 51 (61.4) | |

| Background liver fibrosis1 | F0 | 16 (19.5) |

| F1 | 21 (25.6) | |

| F2 | 10 (12.2) | |

| F3 | 18 (22.0) | |

| F4 | 17 (20.7) | |

| NASH1 | (+) | 10 (12.2) |

| (-) | 72 (87.8) |

The results of the univariate analyses for DFS, OS and DSS by Cox’s proportional hazards model are summarized in Table 2. The factors significantly correlated with DFS were smoking (Ex vs current, P = 0.0271), smoking (current vs other, P = 0.035), portal vein invasion (P = 0.0035), T factor (P = 0.0004), and multiple tumors at the time of surgery (P = 0.0001). No patient had received adjuvant therapy after curative surgery until recurrence.

| DFS | OS | DSS | ||||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age ( ≤ 70 yr) | 0.777 (0.434-1.389) | 0.3948 | 0.959 (0.529-1.739) | 0.8915 | 0.757 (0.360-1.591) | 0.4622 |

| Gender (male) | 0.742 (0.382-1.443) | 0.3796 | 1.466 (0.653-3.291) | 0.3537 | 1.351 (0.515-3.545) | 0.5404 |

| Occult HBV infection | 1.052 (0.564-1.961) | 0.8736 | 1.184 (0.628-2.232) | 0.6009 | 1.328 (0.625-2.821) | 0.4604 |

| Alcohol abuse | 0.700 (0.326-1.503) | 0.3605 | 1.492 (0.749-2.969) | 0.2549 | 1.489 (0.631-3.514) | 0.3639 |

| Smoking (Ex vs current) | 0.405 (0.182-0.903) | 0.0271 | 0.451 (0.215-0.945) | 0.0349 | 0.299 (0.113-0.795) | 0.0155 |

| Smoking (Ex vs never) | 0.680 (0.319-1.453) | 0.3197 | 1.295 (0.597-2.807) | 0.5132 | 0.905 (0.328-2.501) | 0.848 |

| Smoking (current vs never) | 1.680 (0.874-3.230) | 0.1199 | 2.869 (1.417-5.807) | 0.0034 | 3.026 (1.315-6.968) | 0.0092 |

| Smoking (Ex + current vs never) | 1.078 (0.606-1.920) | 0.7976 | 1.926 (1.019-3.640) | 0.0436 | 1.735 (0.804-3.745) | 0.1604 |

| Smoking (current vs other) | 1.926 (1.047-3.544) | 0.035 | 2.569 (1.397-4.724) | 0.0024 | 3.144 (1.497-6.604) | 0.0025 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.894 (0.474-1.685) | 0.7285 | 1.715 (0.941-3.126) | 0.0779 | 1.414 (0.665-3.008) | 0.3681 |

| Pathological NASH | 1.222 (0.516-2.892) | 0.649 | 1.076 (0.423-2.736) | 0.8781 | 1.342 (0.465-3.873) | 0.5863 |

| Obesity | 0.989 (0.535-1.828) | 0.9714 | 1.049 (0.556-1.981) | 0.8827 | 1.183 (0.549-2.549) | 0.6673 |

| Fibrosis | 1.163 (0.699-1.936) | 0.5608 | 1.004 (0.583-1.729) | 0.9883 | 1.407 (0.742-2.670) | 0.2956 |

| Vp | 2.428 (1.338-4.407) | 0.0035 | 1.892 (1.042-3.436) | 0.0362 | 1.918 (0.919-4.002) | 0.0828 |

| T factor (T3/4 vs T1/2) | 3.220 (1.680-6.169) | 0.0004 | 1.793 (0.984-3.268) | 0.0565 | 2.222 (1.052-4.693) | 0.0364 |

| Multiple tumors | 3.275 (1.784-6.014) | 0.0001 | 2.009 (1.110-3.636) | 0.0211 | 2.767 (1.329-5.761) | 0.0065 |

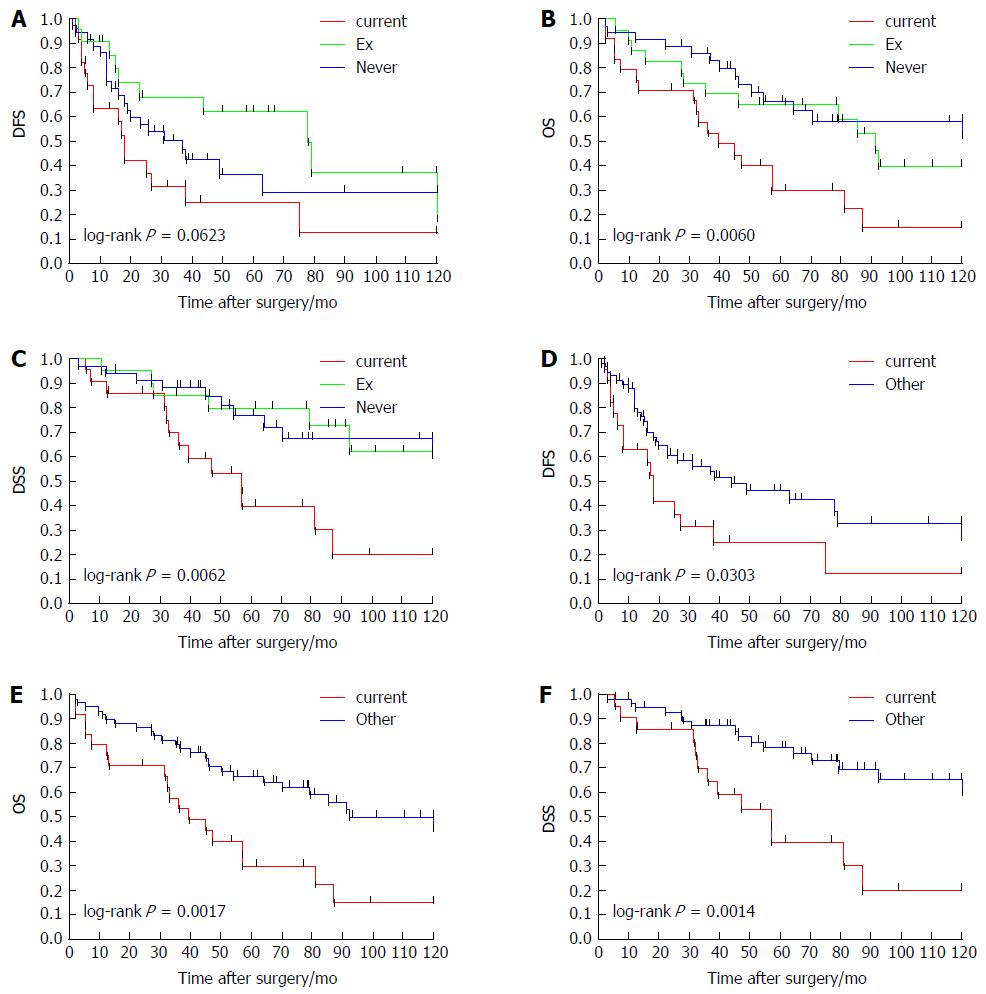

The factors significantly correlated with OS were smoking (Ex vs current, P = 0.0349), smoking (current vs never, P = 0.0034), smoking (Ex + current vs never, P = 0.0436), smoking (current vs other, P = 0.0024), portal vein invasion (P = 0.0362), and multiple tumors at the time of surgery (P = 0.0211). The factors significantly correlated with DSS were smoking [Ex vs current, P = 0.0155, smoking (current vs never, P = 0.0092)], smoking (current vs other; P = 0.0025), T factor (P = 0.0364) and multiple tumors at the time of surgery (P = 0.0065). The survival curves of DFS, OS and DSS according to smoking habit (never, Ex and current) or current smoking habit (current and other) are provided as Figure 1. The current-smoking group showed significantly poor survival curves compared to all other patient groups in each analysis of DFS, OS and DSS.

The results of the multivariate analyses for DFS, OS and DSS by Cox’s proportional hazards model are summarized in Table 3. The only factor that was significantly correlated with DFS was portal vein invasion (P = 0.0229). The factors significantly correlated with OS were smoking (current vs other) and portal vein invasion (P = 0.0058 and P = 0.0061, respectively). The factors significantly correlated with DSS were smoking (current vs other) and portal vein invasion (P = 0.0105 and P = 0.0313, respectively).

| Type | Label | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| DFS | Smoking (current vs other) | 1.897 (0.888-4.054) | 0.0985 |

| Age ( ≤ 70 yr) | 0.627 (0.330-1.191) | 0.1535 | |

| Gender (male) | 0.611 (0.279-1.337) | 0.2176 | |

| Vp | 2.656 (1.145-6.165) | 0.0229 | |

| T factor (T3/4 vs T1/2) | 1.574 (0.537-4.609) | 0.4083 | |

| Multiple tumors | 1.930 (0.807-4.614) | 0.1394 | |

| Alcohol abuse | 0.547 (0.228-1.310) | 0.1755 | |

| OS | Smoking (current vs other) | 2.807 (1.349-5.840) | 0.0058 |

| Age ( ≤ 70 yr) | 1.189 (0.603-2.346) | 0.6177 | |

| Gender (male) | 1.362 (0.555-3.343) | 0.4999 | |

| Vp | 3.069 (1.377-6.839) | 0.0061 | |

| T factor (T3/4 vs T1/2) | 0.532 (0.187-1.512) | 0.2364 | |

| Multiple tumors | 1.830 (0.760-4.405) | 0.1774 | |

| DSS | Smoking (current vs other) | 3.133 (1.307-7.512) | 0.0105 |

| Age ( ≤ 70 yr) | 0.988 (0.424-2.302) | 0.9775 | |

| Gender (male) | 1.406 (0.463-4.271) | 0.5478 | |

| Vp | 2.756 (1.095-6.935) | 0.0313 | |

| T factor (T3/4 vs T1/2) | 0.610 (0.167-2.233) | 0.4555 | |

| Multiple tumors | 2.476 (0.797-7.693) | 0.1169 | |

| Pathological NASH | 2.320 (0.689-7.811) | 0.1741 |

To clarify the characteristics of the current smokers, we further performed subset analyses regarding the clinicopathological factors, treatment and causes of death (Table 4). The current smokers were significantly younger than the Never + Ex patient group (mean age 59.4 year vs 69.3 year, P = 0.0002) at the time of surgery. The current smokers group had significantly greater incidences of alcohol abuse (P = 0.0188) and multiple tumors (P = 0.023). No significant difference was observed in gender, diabetes mellitus, obesity, indocyanine green retention rate at 15 min (ICG R15), tumor size, portal vein invasion, T factor, serum AFP level or liver fibrosis.

| Current (n = 24) | Never + Ex (n = 59) | P value | |

| Age, yr (mean ± SD) | 59.4 ± 12.0 | 69.3 ± 10.2 | 0.0002 |

| Gender (male/female) | 22/2 | 44/15 | 0.0803 |

| Alcohol abuse (+/-) | 10/14 | 9/50 | 0.0188 |

| Diabetes mellitus (+/-) | 8/16 | 21/38 | 0.8448 |

| Obesity (+/-) | 6/18 | 20/39 | 0.6024 |

| ICG R15 (%) | 11.7 ± 1.8 | 14.8 ± 1.2 | 0.1235 |

| Tumor size (mean ± SD mm) | 68.4 ± 44.0 | 63.9 ± 40.6 | 0.6724 |

| Solitary/Multiple | 10/14 | 42/17 | 0.023 |

| Vp (+/-) | 9/15 | 23/36 | 0.8998 |

| T factor (T12/T34) | 10/24 | 33/26 | 0.3329 |

| AFP (mean ± SD) | 4450 ± 14563.6 | 3235 ± 13042 | 0.6442 |

| Fibrosis (F12/F34, n = 82) | 11/13 | 36/22 | 0.2224 |

| Recurrence (+/-) | 16/8 | 32/27 | 0.3362 |

| Therapy for recurrent tumor (+/-)1 | 14/2 | 27/5 | 0.7724 |

| TAE only | 11 | 14 | |

| Surgical resection | 1 | 5 | |

| Ablation | 1 | 2 | |

| Chemotherapy | 1 | 3 | |

| Multiple therapy2 | 0 | 3 | |

| Tumor-related death (%) | 13 (54.2) | 17 (28.8) | 0.0293 |

| Other cause of death (%) | 5 (20.8) | 11 (18.6) | 0.8187 |

Thirteen of the 24 patients (54.2%) in the Current smoking group died of HCC, whereas 17 of the 59 patients (28.8%) in the Never + Ex patient group died of HCC (P = 0.0293). Five of the 24 patients (20.8%) in the Current smoking group died of other causes: cerebral hemorrhage, surgical complication for gastric cancer, pneumoniae (two cases) and sepsis due to pseudomembranous colitis.

In the Never + Ex group, 11 of the 59 patients (18.6%) died of other causes: other malignancy, four patients (two cases of bile duct cancer, prostatic cancer, malignant lymphoma); cerebral infarction, two patients; liver failure, two patients; pneumonia, one patient; sudden cardiac death, one patient and renal failure, one patient.

To determine the influence of etiological differences on the outcomes of the surgical treatment for HCC, many studies have compared surgical outcomes between patients with NBNC-HCC and those with viral-associated HCC, but the results are controversial. Some studies showed that surgical outcomes in patients with NBNC-HCC were not significantly different compared to those of patients with hepatitis virus-related HCC[17,20,23,29]. Other studies reported that NBNC-HCC patients had significantly better surgical outcomes than HCV-HCC patients[18,24,26]. In a recent Japanese nationwide study of 2738 NBNC-HCC patients, the DFS of the NBNC-HCC group was significantly better than those of the HBV-HCC and HCV-HCC groups[16]. For the purpose of clarifying the association between smoking status and surgical outcomes, we focused on NBNC-HCC in the present study because the surgical outcomes of viral-associated HCC may be influenced by cirrhosis due to viral-associated hepatitis.

Many studies have been reported regarding surgical outcomes and etiologies of NBNC-HCC. The relationships between the surgical outcomes of NBNC-HCC and metabolic diseases such as obesity, diabetes mellitus and NAFLD/NASH have been extensively investigated. Several investigations indicated favorable surgical outcomes of NBNC-HCC associated with NAFLD/NASH compared to those of viral-associated HCC[21-32]. It was reported that obesity did not affect survival in patients with NBNC-HCC after curative therapy[29]. In contrast, a large retrospective Japanese multicenter cohort study of 5326 patients with NBNC-HCC indicated that patients with BMI values > 22 and ≤ 25 kg/m2 showed the best prognoses compared to other BMI categories, after adjusting for age, gender, tumor-related factors, and Child-Pugh score[3]. However, these previous studies regarding the surgical results of NBNC-HCC patients did not involve an analysis of smoking habit despite the recognition of smoking as risk factor for NBNC-HCC. We therefore focused on the smoking habit in the present study.

The major finding of the present study is the strong correlation between smoking habit and surgical outcomes. Although emerging epidemiologic data suggest that cigarette smoking may increase the risk of HCC[10-12], the influence of cigarette smoking on HCC survival has not been well documented. We were able to find 10 studies in the English literature that analyzed the correlation of smoking and HCC mortality[33-42]. Large cohort studies indicating an impact of smoking habit on HCC mortality have been reported form Japan[33,34], the United Kingdom[35], China[36] and Taiwan[37-39]. In contrast, several studies reported a negative correlation between HCC mortality and smoking habit, although those studies analyzed relatively small numbers of HCC cases (262-552 cases)[40-42].

Most of the previous studies regarding HCC mortality and smoking habit did not focus on the surgical outcomes of HCC patients or distinguish surgical cases versus nonsurgical cases. We were able to identify only two reports from China that focused on surgical outcomes of HCC patients: Zhang et al[30] analyzed the outcomes of 302 patients with HBV infection who had undergone surgical resection for HCC, and their findings revealed a significant influence of smoking status on both recurrence and mortality. Lv et al[43] investigated the outcomes of 425 patients with a predominant population (74%) of HBV infection who were undergoing hepatectomy for HCC, and those authors’ analysis revealed that cigarette smoking is an independent risk factor for the development of liver-related and infectious complications. We were unable to find any other study reporting the surgical outcomes of NBNC-HCC patients in relation to their smoking status.

In the present study, the survival of the current smokers was significantly poorer than that of the never-smokers, and no significant difference in the survival of the ex-smokers and never-smokers was revealed. We speculate that the reason for the latter finding is due to the long cessation period (> 10 years) for most of the ex-smokers. Our subset analyses comparing the current smokers and the other patients revealed that the current smokers were significantly younger and were more likely to have multiple tumors at the time of surgery. These findings suggest that a smoking habit may affect multicentric liver carcinogenesis. The underlying mechanism of liver carcinogenesis induced by smoking is as yet unclear and should be investigated in further studies.

Generally, alcoholic abuse is known as a poor-prognosis risk factor in surgical treatment for HCC because of the poor liver function of individuals who abuse alcohol. Indeed, in the present study the proportion of alcohol-abusing patients was higher in the current smoking group, but no significant between-group difference was observed in liver function as represented by the ICG R15 or liver fibrosis. Notably, over half of our study’s current-smoker patients died of HCC, and only five of the current smokers died of other causes. Thus, the causes of death in the current-smoker group were significantly different from those of the other patient groups.

Although current smoking was significantly correlated with DFS in our univariate analysis, no such significance was observed in the multivariate analyses, whereas current smoking showed significant correlations with the OS and DSS in the multivariate analyses. One possible reason for this is our study’s small sample size. Another possible reason is that the malignant potential of the recurrent tumors in the current-smoker group may be different from those of the other groups, because the survival after recurrence was significantly different despite the lack of a significant difference in the recurrence rate and the treatments for the recurrent tumors between the current-smoker group and the other groups.

The limitations of the present study are its retrospective design, the relatively small number of patients, and the long study period for enrollment. In addition, information about our patients’ post-surgery smoking status was not available, and thus the effects on survival of a smoking habit after surgery and a smoking habit after recurrence could not be examined. It remains quite regrettable that the previous large case series and multicenter studies did not investigate the HCC patients’ smoking status. We hope a larger prospective study verifies the precise influence of smoking on the survival of patients with NBNC-HCC, as its results can be expected to provide further motivation for smoking cessation.

In conclusion, the results of our single-institute retrospective study indicate that current smoking habit is significantly correlated with the surgical outcomes of patients with NBNC-HCC. Our analyses also revealed that the current smokers were significantly younger than the other patient groups and had significantly greater incidences of alcohol abuse and multiple tumors at the time of surgery.

No previous study has addressed the impact of smoking habit on surgical outcomes or clinicopathological characteristics according to smoking habits in patients with non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma (NBNC-HCC).

The novel findings of this study are (1) current smoking habit at the time of surgical treatment is a risk factor for poor long-term survival in NBNC-HCC patients; and (2) current smokers tend to have multiple HCCs at a younger age than other patients.

The results of present study can be expected to provide further motivation for smoking cessation.

NBNC-HCC is defined as hepatocellular carcinoma that has arisen in an individual who is negative for both hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C antibody. Alcohol abuse was defined as a daily ethanol intake > 40 g for men and > 20 g for women. Obesity was defined as a body mass index > 25 kg/m2 in both genders. A current smoker was defined as an individual who regularly smoked and continued to smoke within 1 year prior to the surgery. An ex-smoker was defined as an individual who quit smoking at least 1 year before his or her surgery.

An interesting paper about risk factors in patients with NBNC hepatocellular cancer. Results are adequate and conclusions are very clear.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Bueno-Lledó J, Facciorusso A S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Bosetti C, Levi F, Boffetta P, Lucchini F, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Trends in mortality from hepatocellular carcinoma in Europe, 1980-2004. Hepatology. 2008;48:137-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Nishiguchi S, Kuroki T, Nakatani S, Morimoto H, Takeda T, Nakajima S, Shiomi S, Seki S, Kobayashi K, Otani S. Randomised trial of effects of interferon-alpha on incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic active hepatitis C with cirrhosis. Lancet. 1995;346:1051-1055. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Tateishi R, Okanoue T, Fujiwara N, Okita K, Kiyosawa K, Omata M, Kumada H, Hayashi N, Koike K. Clinical characteristics, treatment, and prognosis of non-B, non-C hepatocellular carcinoma: a large retrospective multicenter cohort study. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:350-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Seeff LB, Hoofnagle JH. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in areas of low hepatitis B and hepatitis C endemicity. Oncogene. 2006;25:3771-3777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Su GL, Conjeevaram HS, Emick DM, Lok AS. NAFLD may be a common underlying liver disease in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2002;36:1349-1354. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Yasui K, Hashimoto E, Komorizono Y, Koike K, Arii S, Imai Y, Shima T, Kanbara Y, Saibara T, Mori T. Characteristics of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis who develop hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:428-433; quiz e50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, McClain M, Craig W. Hereditary haemochromatosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in males: a strategy for estimating the potential for primary prevention. J Med Screen. 2003;10:11-13. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Moucari R, Rautou PE, Cazals-Hatem D, Geara A, Bureau C, Consigny Y, Francoz C, Denninger MH, Vilgrain V, Belghiti J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Budd-Chiari syndrome: characteristics and risk factors. Gut. 2008;57:828-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Suzuki Y, Ohtake T, Nishiguchi S, Hashimoto E, Aoyagi Y, Onji M, Kohgo Y. Survey of non-B, non-C liver cirrhosis in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:1020-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hara M, Tanaka K, Sakamoto T, Higaki Y, Mizuta T, Eguchi Y, Yasutake T, Ozaki I, Yamamoto K, Onohara S. Case-control study on cigarette smoking and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among Japanese. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:93-97. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Tanaka K, Tsuji I, Wakai K, Nagata C, Mizoue T, Inoue M, Tsugane S. Cigarette smoking and liver cancer risk: an evaluation based on a systematic review of epidemiologic evidence among Japanese. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006;36:445-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Koh WP, Robien K, Wang R, Govindarajan S, Yuan JM, Yu MC. Smoking as an independent risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1430-1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Takenaka K, Yamamoto K, Taketomi A, Itasaka H, Adachi E, Shirabe K, Nishizaki T, Yanaga K, Sugimachi K. A comparison of the surgical results in patients with hepatitis B versus hepatitis C-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1995;22:20-24. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Sasaki Y, Yamada T, Tanaka H, Ohigashi H, Eguchi H, Yano M, Ishikawa O, Imaoka S. Risk of recurrence in a long-term follow-up after surgery in 417 patients with hepatitis B- or hepatitis C-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2006;244:771-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kao WY, Su CW, Chau GY, Lui WY, Wu CW, Wu JC. A comparison of prognosis between patients with hepatitis B and C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing resection surgery. World J Surg. 2011;35:858-867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Utsunomiya T, Shimada M, Kudo M, Ichida T, Matsui O, Izumi N, Matsuyama Y, Sakamoto M, Nakashima O, Ku Y. A comparison of the surgical outcomes among patients with HBV-positive, HCV-positive, and non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma: a nationwide study of 11,950 patients. Ann Surg. 2015;261:513-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yamashita Y, Imai D, Bekki Y, Kimura K, Matsumoto Y, Nakagawara H, Ikegami T, Yoshizumi T, Shirabe K, Aishima S. Surgical Outcomes of Hepatic Resection for Hepatitis B Virus Surface Antigen-Negative and Hepatitis C Virus Antibody-Negative Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:2279-2285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kaibori M, Ishizaki M, Matsui K, Kwon AH. Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with non-B non-C hepatitis virus hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. Am J Surg. 2012;204:300-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kaneda K, Kubo S, Tanaka H, Takemura S, Ohba K, Uenishi T, Kodai S, Shinkawa H, Urata Y, Sakae M. Features and outcome after liver resection for non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:1889-1892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Li T, Qin LX, Gong X, Zhou J, Sun HC, Qiu SJ, Ye QH, Wang L, Fan J. Hepatitis B virus surface antigen-negative and hepatitis C virus antibody-negative hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical characteristics, outcome, and risk factors for early and late intrahepatic recurrence after resection. Cancer. 2013;119:126-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wakai T, Shirai Y, Sakata J, Korita PV, Ajioka Y, Hatakeyama K. Surgical outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1450-1458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Reddy SK, Steel JL, Chen HW, DeMateo DJ, Cardinal J, Behari J, Humar A, Marsh JW, Geller DA, Tsung A. Outcomes of curative treatment for hepatocellular cancer in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis versus hepatitis C and alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2012;55:1809-1819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pawlik TM, Poon RT, Abdalla EK, Sarmiento JM, Ikai I, Curley SA, Nagorney DM, Belghiti J, Ng IO, Yamaoka Y. Hepatitis serology predicts tumor and liver-disease characteristics but not prognosis after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:794-804; discussion 804-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Li Q, Li H, Qin Y, Wang PP, Hao X. Comparison of surgical outcomes for small hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis B versus hepatitis C: a Chinese experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1936-1941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nanashima A, Abo T, Sumida Y, Takeshita H, Hidaka S, Furukawa K, Sawai T, Yasutake T, Masuda J, Morisaki T. Clinicopathological characteristics of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy: relationship with status of viral hepatitis. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:487-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kondo K, Chijiiwa K, Funagayama M, Kai M, Otani K, Ohuchida J. Differences in long-term outcome and prognostic factors according to viral status in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:468-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cescon M, Cucchetti A, Grazi GL, Ferrero A, Viganò L, Ercolani G, Ravaioli M, Zanello M, Andreone P, Capussotti L. Role of hepatitis B virus infection in the prognosis after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis: a Western dual-center experience. Arch Surg. 2009;144:906-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zhou Y, Si X, Wu L, Su X, Li B, Zhang Z. Influence of viral hepatitis status on prognosis in patients undergoing hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nishikawa H, Arimoto A, Wakasa T, Kita R, Kimura T, Osaki Y. Comparison of clinical characteristics and survival after surgery in patients with non-B and non-C hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer. 2013;4:502-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zhang XF, Wei T, Liu XM, Liu C, Lv Y. Impact of cigarette smoking on outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma after surgery in patients with hepatitis B. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ichida F, Tsuji T, Omata M, Ichida T, Inoue K, Kamimura T, Yamada G, Hino K, Yokosuka O, Suzuki H. New Inuyama classification; new criteria for histological assessment of chronic hepatitis. Int Hepatol Commun. 1996;6:112-119. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Cauchy F, Fuks D, Nomi T, Schwarz L, Barbier L, Dokmak S, Scatton O, Belghiti J, Soubrane O, Gayet B. Risk factors and consequences of conversion in laparoscopic major liver resection. Br J Surg. 2015;102:785-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ogimoto I, Shibata A, Kurozawa Y, Nose T, Yoshimura T, Suzuki H, Iwai N, Sakata R, Fujita Y, Ichikawa S. Risk of death due to hepatocellular carcinoma among smokers and ex-smokers. Univariate analysis of JACC study data. Kurume Med J. 2004;51:71-81. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Fujita Y, Shibata A, Ogimoto I, Kurozawa Y, Nose T, Yoshimura T, Suzuki H, Iwai N, Sakata R, Ichikawa S. The effect of interaction between hepatitis C virus and cigarette smoking on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:737-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Batty GD, Kivimaki M, Gray L, Smith GD, Marmot MG, Shipley MJ. Cigarette smoking and site-specific cancer mortality: testing uncertain associations using extended follow-up of the original Whitehall study. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:996-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Evans AA, Chen G, Ross EA, Shen FM, Lin WY, London WT. Eight-year follow-up of the 90,000-person Haimen City cohort: I. Hepatocellular carcinoma mortality, risk factors, and gender differences. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:369-376. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Shih WL, Chang HC, Liaw YF, Lin SM, Lee SD, Chen PJ, Liu CJ, Lin CL, Yu MW. Influences of tobacco and alcohol use on hepatocellular carcinoma survival. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2612-2621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Tseng CH. Type 2 diabetes, smoking, insulin use, and mortality from hepatocellular carcinoma: a 12-year follow-up of a national cohort in Taiwan. Hepatol Int. 2013;7:693-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Chiang CH, Lu CW, Han HC, Hung SH, Lee YH, Yang KC, Huang KC. The Relationship of Diabetes and Smoking Status to Hepatocellular Carcinoma Mortality. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Wong LL, Limm WM, Tsai N, Severino R. Hepatitis B and alcohol affect survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3491-3497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Siegel AB, Conner K, Wang S, Jacobson JS, Hershman DL, Hidalgo R, Verna EC, Halazun K, Brubaker W, Zaretsky J. Smoking and hepatocellular carcinoma mortality. Exp Ther Med. 2012;3:124-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Raffetti E, Portolani N, Molfino S, Baiocchi GL, Limina RM, Caccamo G, Lamera R, Donato F. Role of aetiology, diabetes, tobacco smoking and hypertension in hepatocellular carcinoma survival. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:950-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Lv Y, Liu C, Wei T, Zhang JF, Liu XM, Zhang XF. Cigarette smoking increases risk of early morbidity after hepatic resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:513-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |