Published online Nov 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i44.7875

Peer-review started: August 19, 2017

First decision: August 29, 2017

Revised: September 4, 2017

Accepted: September 13, 2017

Article in press: September 13, 2017

Published online: November 28, 2017

Processing time: 99 Days and 21.4 Hours

To investigate the efficacy and safety of a combination of sufentanil and propofol injection in patients undergoing endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) for esophageal varices (EVs).

Patients with severe EVs who underwent EIS with sufentanil and propofol anesthesia between April 2016 and July 2016 at our hospital were reviewed. Although EIS and sequential therapy were performed under endotracheal intubation, we only evaluated the efficacy and safety of anesthesia for the first EIS procedure. Patients were intravenously treated with 0.5-1 μg/kg sufentanil. Anesthesia was induced with 1-2 mg/kg propofol and maintained using 2-5 mg/kg per hour of propofol. Information, regarding age, sex, weight, American Association of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status, Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) classification, indications, preanesthetic problems, endoscopic procedure, successful completion of the procedure, anesthesia time, recovery time, and anesthetic agents, was recorded. Adverse events, including hypotension, hypertension, bradycardia, and hypoxia, were also noted.

Propofol and sufentanil anesthesia was provided in 182 procedures involving 140 men and 42 women aged 56.1 ± 11.7 years (range, 25-83 years). The patients weighed 71.4 ± 10.7 kg (range, 45-95 kg) and had ASA physical status classifications of II (79 patients) or III (103 patients). Ninety-five patients had a CTP classification of A and 87 had a CTP classification of B. Intravenous anesthesia was successful in all cases. The mean anesthesia time was 33.1 ± 5.8 min. The mean recovery time was 12.3 ± 3.7 min. Hypotension occurred in two patients (1.1%, 2/182). No patient showed hypertension during the endoscopic therapy procedure. Bradycardia occurred in one patient (0.5%, 1/182), and hypoxia occurred in one patient (0.5%, 1/182). All complications were easily treated with no adverse sequelae. All endoscopic procedures were completed successfully.

The combined use of propofol and sufentanil injection in endotracheal intubation-assisted EIS for EVs is effective and safe.

Core tip: Propofol is widely used during painless endoscopy because of its rapid onset and rapid recovery properties. Intravenous injection of propofol during endoscopic esophageal varices therapy can reduce the complications associated with poor patient cooperation. Because of complications related to bleeding during endoscopic variceal ligation and endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS), endotracheal intubation is essential for these procedures. However, due to its weak analgesic effect, intraoperative pain stimulation is greater, leading to overt physical movement, thus affecting the operation. Since analgesics are often required to ensure a successful operation, in this study, we used a combination of sufentanil and propofol injection for the endoscopic treatment of esophageal varices. In conclusion, sufentanil and propofol injection, with endotracheal intubation-assisted EIS is effective and safe.

- Citation: Yu Y, Qi SL, Zhang Y. Role of combined propofol and sufentanil anesthesia in endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for esophageal varices. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(44): 7875-7880

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i44/7875.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i44.7875

Esophageal varices (EVs), a form of port-systemic collateral vessels, occur as a result of portal hypertension. Rupture of EVs can cause variceal hemorrhage, which is among the most common lethal complications of liver cirrhosis[1]. Since the red color sign (RCS) is considered to be a sign of bleeding of EVs[2], identification of the RCS is thought to be necessary to prevent potentially fatal massive bleeding from EVs.

Although endoscopic findings are typically evaluated with the naked eye, this approach cannot be used to assess deep collateral vessels to identify the RCS. Therefore, endoscopic ultrasonography, which was developed to evaluate diseases of the mediastinum, is used to visualize the collateral channels that surround the distal esophagus and upper stomach[3-10], and may enhance variceal detection and improve therapeutic targeting[11-20]. Endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) and endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) are the two major techniques used in endoscopic EV therapy[21].

Propofol is widely used during painless endoscopy because of its rapid onset and rapid recovery properties[22,23]. Intravenous injection of propofol during endoscopic EV therapy can reduce the complications associated with poor patient cooperation. Because of complications related to bleeding during EVL or EIS, endotracheal intubation is essential for these procedures. However, due to its weak analgesic effect, intraoperative pain stimulation is greater, leading to overt physical movements, thus affecting the operation. Since analgesics are often required to ensure a successful operation[24], in this study, we used a combination of sufentanil and propofol injection for the endoscopic treatment of EVs, and evaluated the safety and efficacy of this combination.

Patients who underwent EIS for EVs at the Sixth People’s Hospital of Dalian from April 2016 to July 2016 were enrolled in this study. The diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was based on histological or clinical factors. The patients had American Association of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classifications of II (79 patients) or III (103 patients) and Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) classifications of A (95 patients) or B (87 patients). The inclusion criteria were EV grade ≥ F2, as a prerequisite, and moderate to severe RCS, as indicated in the general rules for recording endoscopic findings for EV. The following cases were excluded: (1) emergency cases in which the EVs had ruptured; (2) cases in which anesthesia was not possible; (3) cases with portal venous obstruction; (4) cases with thrombocytopenia (< 4 × 104/μL); and (5) cases with high CTP grades (C).

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of The Sixth People’s Hospital of Dalian, Dalian, China. All patients voluntarily chose their own therapeutic course and provided written informed consent for their participation in this study.

Standard monitoring was performed in the endoscopy center and included electrocardiography, noninvasive arterial blood pressure monitoring, and pulse oximetry. Bispectral index (BIS) values (A2000 BIS XP monitor, version 3.2; Aspect Medical System, Inc.; Newton, MA, United States) were obtained and recorded. The BIS smoothing period was set to 15 s.

EIS was performed using a standard endoscope (SV-290; Olympus Corporation; Tokyo, Japan). The endoscopic puncture needle used for EIS was a 23-gauge Varixer needle (Single Use Injector NM-400L-0423; Olympus Corporation; Tokyo, Japan). We performed 3-5 punctures per EV. We used lauromacrogol injection (10 mL/100 mg, Tianyu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Xi’an, China) as the sclerosant in a low-cost and efficient EIS procedure that was technically easy to perform. All patients were treated by a single operator who had more than 10 years of experience as an endoscopist. The operator also had more than 5 years of experience as the main EIS operator.

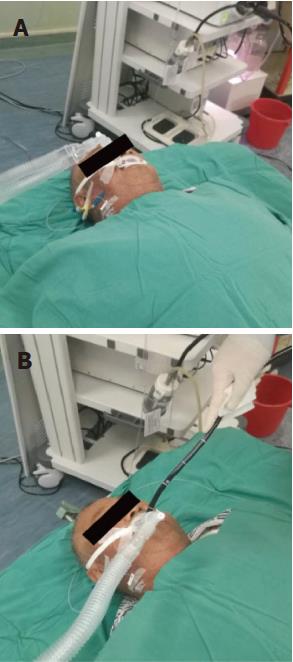

The patients were placed in the supine position. Electrocardiography, noninvasive arterial blood pressure monitoring, and pulse oximetry were performed. We injected 0.5-1 μg/kg sufentanil to induce mild sedation and suppressed the stress response during intubation. Anesthesia was induced using 1-2 mg/kg propofol and maintained using 2-5 mg/kg propofol per hour. Scoline and cisatracurium were injected as a part of the endotracheal intubation procedure. EIS was performed after endotracheal intubation (Figure 1).

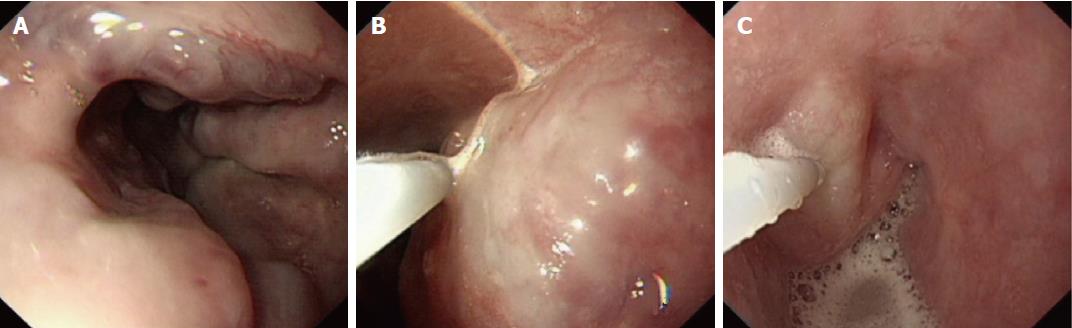

Intravariceal injection sequential therapy was also performed (Figure 2). Patients with EVs of grades ≥ F2 and a moderate to severe RCS were included in the study. The sequential therapy was carried out over two sessions. During the first session, two EIS procedures were performed at a 7-d interval. The puncture was performed 3-5 times per esophageal varix, from the cardia to the esophagus. Two weeks after the first session, gastroscopy was performed to evaluate the EVs. If the EVs were still present, the patient was treated a second time. In order to exclude interclass bias, in this study, we evaluated data related to the first endoscopic procedure only.

The following data were obtained: Age, sex, weight, ASA physical status, CTP classification, indications, preanesthetic problems, endoscopic procedure, successful completion of the procedure, anesthesia time, and anesthesia agents. Adverse events were also recorded, including hypotension (defined as a blood pressure reduction of 20% from baseline and below normal for the patient’s age), hypertension (defined as a blood pressure elevation of 20% from baseline and above normal for the patient’s age), bradycardia (defined as a heart rate reduction of 30% from baseline and below normal for the patient’s age), and hypoxia (defined as oxygen desaturation with SpO2 < 90%). All anesthesia procedures were conducted by an experienced anesthetist.

After the endoscopic treatment, patients were followed up for at least 6 mo through bedside appointment or telephone contact to assess re-bleeding, complications, and mortality.

The patients received propofol and sufentanil injections during endotracheal intubation. Propofol anesthesia was provided during 182 procedures involving patients (140 men and 42 women) aged 56.1 ± 11.7 years (range, 25-83 years) and weighing 71.4 ± 10.7 kg (range, 45 - 95 kg). The mean anesthesia time was 33.1 ± 5.8 min. The mean recovery time was 12.3 ± 3.7 min. Hypotension occurred in two patients (1.1%, 2/182). In 1 patient, the blood pressure decreased from 135/80 mmHg to 100/60 mmHg during the endoscopic procedure. After rapid rehydration, the blood pressure returned to 130/75 mmHg. For the other patient, the blood pressure decreased from 145/90 mmHg to 108/65 mmHg during the endoscopic procedure. After rapid rehydration, blood pressure returned to 135/75 mmHg. No patient developed hypertension during endoscopy. Bradycardia and hypoxia occurred in one patient each (1/182; 0.5%). In this patient, the heart rate decreased from 82 beats per minute (bpm) to 56 bpm. After intravenous injection of 0.5 mg atropine, the heart rate returned to 77 bpm. All complications were easily treated, with no adverse sequelae. Intravenous anesthesia was successful. In addition, all endoscopic procedures were completed successfully.

In the study, the observed complications were minor and did not require intervention. After two therapy sessions, the recurrence rate of EVs was lower than 5% at the 1-year follow-up. Esophageal stenosis occurred in four patients at about 2 wk after the last EIS. The symptoms of esophageal stenosis were relieved after endoscopic balloon dilation.

In the present study, propofol was administered in combination with sufentanil to patients who underwent EIS for esophageal varices. The combination was found to facilitate safe and successful completion of the EIS procedure.

Portal hypertension increases blood flow and results in engorgement of the collateral vessels surrounding the lower esophagus and proximal stomach, leading to a build-up of gastroesophageal varices in approximately 50% of patients with cirrhosis[25]. Once varices have been diagnosed, variceal bleeding has been reported to occur at a yearly rate of 10% - 15%[26], and is associated with high morbidity and mortality in patients with liver cirrhosis. Treatment for prevention of EV bleeding is therefore required when large varices are present.

EIS or EVL is the initial endoscopic treatment selected for EVs. The 4th International Baveno Consensus[27] on Portal Hypertension recommends band ligation as the first-choice therapy, with sclerotherapy as a second-choice procedure. Ligation leads to lower complication rates and higher survival rates[28,29]. Additionally, EVL is popular worldwide because of the convenience of the procedure. However, the 5-year cumulative recurrence rate of EVs after EIS using intravariceal injection is 32%[30], which is markedly lower than that after EVL (80%)[31-33]. According to Triantos and colleagues[34], when band ligation is employed, it is necessary to withdraw the endoscope for system assembly, potentially increasing the duration of the procedure and the risk of complications. Hence, EIS was selected for the present study.

EIS is typically performed using one of the two methods. The first involves mucosal injection of sclerosant around the EVs, which results in a lower incidence of bleeding complications, while the other involves intravariceal injection of sclerosant, which is more effective. We performed intravariceal injection and sequential therapy in this study and achieved a success rate of 100%. Although EIS is an inexpensive, easily performed, and effective method, there are several complications associated with this technique. A previous study showed that minor complications such as low-grade fever, chest pain, and dysphagia can occur within the first 24-48 h after the procedure; however, they do not require treatment[1]. Local complications, such as esophageal ulcers, ulcer-related bleeding, and esophageal strictures, are also associated with EIS. Most of these complications occur due to incorrect injections or high sclerosant concentrations[1] and usually heal after omeprazole treatment. Esophageal stenosis occurs in 2%-10% of cases. In this study, the observed complications were minor and did not require intervention. After two treatment sessions, the recurrence rate of EVs was lower than 5% at the 1-year follow-up. Esophageal stenosis occurred in four patients about 2 wk after the last EIS. The symptoms of esophageal stenosis were relieved after endoscopic balloon dilation.

Esophagogastric varices are the most significant type of varices because their rupture results in variceal hemorrhage, which is among the most common lethal complications of cirrhosis. The presence of cirrhosis is independently associated with a 47% increase in the risk of postoperative complications and a greater than 2-fold increase in the risk of in-hospital mortality in patients undergoing elective surgery[35]. CTP scores have traditionally been used to assess the risk of mortality in patients with liver disease scheduled to undergo surgery[36-39]. Therefore, anesthesia for patients with liver cirrhosis is a significant challenge. The choice of anesthetic agent is based on variables such as protein binding, distribution, and drug metabolism. For procedures requiring sedation, propofol is preferable to benzodiazepines, as it has a shorter time to sedation and a shorter recovery time in patients with cirrhosis[40]. Propofol is widely used because of its rapid onset and high recovery quality in painless endoscopy. Intravenous injection of propofol for endoscopic EV therapy can reduce the complications associated with poor cooperation of the patient and increase the comfort level of the patient during the endoscopic treatment. However, because of its weak analgesic effect, intraoperative pain stimulation is greater under propofol anesthesia and often appears in the form of marked physical movements, which may in turn affect the operation. Therefore, analgesics are often required to complete the operation. In the study by Zhang et al[22], pain levels in 439 patients were evaluated after injections of propofol and different combinations of fentanyl, sufentanil, or remifentanil at doses of 0.1 μg/kg or 0.05 μg/kg during gastrointestinal endoscopy. They observed that the incidence of pain in the group that was administered both propofol and half the dose sufentanil (0.05 μg/kg) was significantly lower (33%) than that in the other groups.

In this study, propofol was combined with sufentanil. Considering that this combination was effective at half the dose, we used this dose, as our study included patients with liver dysfunction. The dosage of anesthetic drug used did not affect anesthesia. The complication rate was very low, and the complications were easily treated with no adverse sequelae. The mean recovery time was less than 13 min.

In conclusion, propofol and sufentanil injection during endotracheal intubation-assisted EIS is effective and safe. Controlled clinical trials with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are necessary to further evaluate the value and limitations of this technique.

Propofol is widely used during painless endoscopy because of its rapid onset and rapid recovery properties. Intravenous injection of propofol during endoscopic esophageal varices therapy can reduce the complications associated with poor patient cooperation. Because of complications related to bleeding during endoscopic variceal ligation and endoscopic injection sclerotherapy, endotracheal intubation is essential for these procedures. However, due to its weak analgesic effect, intraoperative pain stimulation is greater, leading to overt physical movements, and thus affecting the operation. Since analgesics are often required to ensure a successful operation, in this study, authors used a combination of sufentanil and propofol injection for the endoscopic treatment of esophageal varices.

In the present study, propofol was administered in combination with sufentanil to patients who underwent EIS for esophageal varices. The combination was found to facilitate safe and successful completion of the EIS procedure.

To investigate the efficacy and safety of a combination of sufentanil and propofol injection in patients undergoing endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for esophageal varices (EVs).

Patients with severe EVs who underwent EIS with sufentanil and propofol anesthesia between April 2016 and July 2016 were reviewed. Although at them hospital and sequential therapy were performed under endotracheal intubation, the authors only evaluated the efficacy and safety of anesthesia for the first EIS procedure. Patients were intravenously treated with 0.5-1 μg/kg sufentanil. Anesthesia was induced with 1-2 mg/kg propofol and maintained using 2-5 mg/kg propofol per hour. Information regarding age, sex, weight, American Association of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status, Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) classification, indications, preanesthetic problems, endoscopic procedure, successful completion of the procedure, anesthesia time, recovery time, and anesthetic agents was recorded. Adverse events, including hypotension, hypertension, bradycardia, and hypoxia, were also noted.

Propofol and sufentanil anesthesia was provided in 182 procedures involving 140 men and 42 women aged 56.1 ± 11.7 years (range, 25-83 years). The patients weighed 71.4 ± 10.7 kg (range, 45-95 kg) and had ASA physical status classifications of II (79 patients) or III (103 patients). Ninety-five patients had a CTP classification of A and 87 had a CTP classification of B. Intravenous anesthesia was successful in all cases. The mean anesthesia time was 33.1 ± 5.8 min. The mean recovery time was 12.3 ± 3.7 min. Hypotension occurred in 2 patients (1.1%, 2/182). No patient showed hypertension during the endoscopic therapy procedure. Bradycardia occurred in 1 patient (0.5%, 1/182), and hypoxia occurred in 1 patient (0.5%, 1/182). All complications were easily treated with no adverse sequelae. In addition, all endoscopic procedures were completed successfully.

The use of propofol and sufentanil injection in endotracheal intubation-assisted EIS for EVs is effective and safe.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Ismail M, Kesavadevi J, LaRue S S- Editor: Wei LJ L- Editor: Ma JY E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Miyaaki H, Ichikawa T, Taura N, Miuma S, Isomoto H, Nakao K. Endoscopic management of esophagogastric varices in Japan. Ann Transl Med. 2014;2:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tajiri T, Yoshida H, Obara K, Onji M, Kage M, Kitano S, Kokudo N, Kokubu S, Sakaida I, Sata M. General rules for recording endoscopic findings of esophagogastric varices (2nd edition). Dig Endosc. 2010;22:1-9. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Dietrich CF, Jenssen C, Arcidiacono PG, Cui XW, Giovannini M, Hocke M, Iglesias-Garcia J, Saftoiu A, Sun S, Chiorean L. Endoscopic ultrasound: Elastographic lymph node evaluation. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:176-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Saxena P, Lakhtakia S. Endoscopic ultrasound guided vascular access and therapy (with videos). Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:168-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang S, Wang S, Liu W, Sun S, Liu X, Ge N, Guo J, Wang G, Feng L. The application of linear endoscopic ultrasound in the patients with esophageal anastomotic strictures. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:126-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dincer HE, Gliksberg EP, Andrade RS. Endoscopic ultrasound and/or endobronchial ultrasound-guided needle biopsy of central intraparenchymal lung lesions not adjacent to airways or esophagus. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:40-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Konge L, Colella S, Vilmann P, Clementsen PF. How to learn and to perform endoscopic ultrasound and endobronchial ultrasound for lung cancer staging: A structured guide and review. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:4-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mangiavillano B, De Ceglie A, Quilici P, Ruggeri C. EUS-FNA diagnosis of a rare case of esophageal teratoma. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:279-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Meena N, Hulett C, Patolia S, Bartter T. Exploration under the dome: Esophageal ultrasound with the ultrasound bronchoscope is indispensible. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:254-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sharma V, Rana SS, Chhabra P, Sharma R, Gupta N, Bhasin DK. Primary esophageal tuberculosis mimicking esophageal cancer with vascular involvement. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:61-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sato T, Yamazaki K. Endoscopic color Doppler ultrasonography for esophagogastric varices. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2012;2012:859213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Men C, Zhang G. Endoscopic ultrasonography predicts early esophageal variceal bleeding in liver cirrhosis: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hall PS, Teshima C, May GR, Mosko JD. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Vascular Therapy: The Present and the Future. Clin Endosc. 2017;50:138-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Carneiro FO, Retes FA, Matuguma SE, Albers DV, Chaves DM, Dos Santos ME, Herman P, Chaib E, Sakai P, Carneiro D’Albuquerque LA. Role of EUS evaluation after endoscopic eradication of esophageal varices with band ligation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:400-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fujii-Lau LL, Law R, Wong Kee Song LM, Gostout CJ, Kamath PS, Levy MJ. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided coil injection therapy of esophagogastric and ectopic varices. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:1396-1404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Masalaite L, Valantinas J, Stanaitis J. Endoscopic ultrasound findings predict the recurrence of esophageal varices after endoscopic band ligation: a prospective cohort study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:1322-1330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hikichi T, Obara K, Nakamura S, Irisawa A, Ohira H. Potential application of interventional endoscopic ultrasonography for the treatment of esophageal and gastric varices. Dig Endosc. 2015;27 Suppl 1:17-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hammoud GM, Ibdah JA. Utility of endoscopic ultrasound in patients with portal hypertension. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14230-14236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liao WC, Chen PH, Hou MC, Chang CJ, Su CW, Lin HC, Lee FY. Endoscopic ultrasonography assessment of para-esophageal varices predicts efficacy of propranolol in preventing recurrence of esophageal varices. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:342-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shim JJ. Usefulness of endoscopic ultrasound in esophagogastric varices. Clin Endosc. 2012;45:324-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Triantos C, Kalafateli M. Endoscopic treatment of esophageal varices in patients with liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13015-13026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Zhang L, Bao Y, Shi D. Comparing the pain of propofol via different combinations of fentanyl, sufentanil or remifentanil in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Acta Cir Bras. 2014;29:675-680. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Hsu WH, Wang SS, Shih HY, Wu MC, Chen YY, Kuo FC, Yang HY, Chiu SL, Chu KS, Cheng KI. Low effect-site concentration of propofol target-controlled infusion reduces the risk of hypotension during endoscopy in a Taiwanese population. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:147-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhao YJ, Liu S, Mao QX, Ge HJ, Wang Y, Huang BQ, Wang WC, Xie JR. Efficacy and safety of remifentanil and sulfentanyl in painless gastroscopic examination: a prospective study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015;25:e57-e60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W; Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1229] [Cited by in RCA: 1210] [Article Influence: 67.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jeong SW, Kim HS, Kim SG, Yoo JJ, Jang JY, Lee SH, Kim HS, Lee JS, Kim YS, Kim BS. Useful Endoscopic Ultrasonography Parameters and a Predictive Model for the Recurrence of Esophageal Varices and Bleeding after Variceal Ligation. Gut Liver. 2017;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | de Franchis R. Evolving consensus in portal hypertension. Report of the Baveno IV consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2005;43:167-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 794] [Cited by in RCA: 733] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Laine L, Cook D. Endoscopic ligation compared with sclerotherapy for treatment of esophageal variceal bleeding. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:280-287. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Villanueva C, Piqueras M, Aracil C, Gómez C, López-Balaguer JM, Gonzalez B, Gallego A, Torras X, Soriano G, Sáinz S. A randomized controlled trial comparing ligation and sclerotherapy as emergency endoscopic treatment added to somatostatin in acute variceal bleeding. J Hepatol. 2006;45:560-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tomikawa M, Hashizume M, Okita K, Kitano S, Ohta M, Higashi H, Akahoshi T. Endoscopic injection sclerotherapy in the management of 2105 patients with esophageal varices. Surgery. 2002;131:S171-S175. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Sarin SK, Govil A, Jain AK, Guptan RC, Issar SK, Jain M, Murthy NS. Prospective randomized trial of endoscopic sclerotherapy versus variceal band ligation for esophageal varices: influence on gastropathy, gastric varices and variceal recurrence. J Hepatol. 1997;26:826-832. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Svoboda P, Kantorová I, Ochmann J, Kozumplík L, Marsová J. A prospective randomized controlled trial of sclerotherapy vs ligation in the prophylactic treatment of high-risk esophageal varices. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:580-584. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Yoshida H, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Yamamoto K, Kawano Y, Mizuguchi Y, Shimizu T, Takahashi T, Tajiri T. A randomized control trial of bi-monthly versus bi-weekly endoscopic variceal ligation of esophageal varices. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2005-2009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Triantos CK, Goulis J, Patch D, Papatheodoridis GV, Leandro G, Samonakis D, Cholongitas E, Burroughs AK. An evaluation of emergency sclerotherapy of varices in randomized trials: looking the needle in the eye. Endoscopy. 2006;38:797-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | International Surgical Outcomes Study group. Global patient outcomes after elective surgery: prospective cohort study in 27 low-, middle- and high-income countries. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117:601-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 459] [Cited by in RCA: 414] [Article Influence: 46.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Zhang HY, Li WB, Ye H, Xiao ZY, Peng YR, Wang J. Long-term results of the paraesophagogastric devascularization with or without esophageal transection: which is more suitable for variceal bleeding? World J Surg. 2014;38:2105-2112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Zhang X, Fan F, Huo Y, Xu X. Identifying the optimal blood pressure target for ideal health. J Transl Intern Med. 2016;4:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Foskett-Tharby R, Hex N, Gill P. Pay for performance and the management of hypertension. J Transl Intern Med. 2016;4:14-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Brennan MD. The role of professionalism in clinical practice, medical education, biomedical research and health care administration. J Transl Intern Med. 2016;4:64-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kiamanesh D, Rumley J, Moitra VK. Monitoring and managing hepatic disease in anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111 Suppl 1:i50-i61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |