Published online Nov 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i43.7746

Peer-review started: July 24, 2017

First decision: August 30, 2017

Revised: September 12, 2017

Accepted: October 28, 2017

Article in press: October 28, 2017

Published online: November 21, 2017

Processing time: 121 Days and 10.7 Hours

To focus on procedure-related complications, evaluate their incidence, analyze the reasons and discuss the solutions.

Overall, 628 endoscopic gastric variceal obturation (EGVO) procedures (case-times) with NBC were performed in 519 patients in the Department of Endoscopy of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University from January 2011 to December 2016. The clinical data of patients and procedure-related complications of EGVO were retrospectively analyzed.

In the 628 EGVO procedures, sticking of the needle to the varix occurred in 9 cases (1.43%), including 1 case that used lipiodol-diluted NBC and 8 cases that used undiluted NBC (P = 0.000). The needle was successfully withdrawn in 8 cases. Large spurt bleeding occurred in one case, and hemostasis was achieved by two other injections of undiluted glue. The injection catheter became blocked in 17 cases (2.71%) just during the injection, and 4 cases were complicated with the needle sticking to the varix. Large glue adhesion to the endoscope resulted in difficulty withdrawing the endoscope in 1 case. Bleeding from multiple sites was observed in the esophagus and gastric cardia after the endoscope was withdrawn. Hemostasis was achieved by 1% aethoxysklerol injection and intravenous somatostatin. The ligation device stuck to the varices in two cases during the subsequent endoscopic variceal ligation. In one case, the ligation device was successfully separated from the esophageal varix after all bands were released. In another case, a laceration of the vein and massive bleeding were observed. The bleeding ceased after 1% aethoxysklerol injection.

Although EGVO with tissue glue is usually safe and effective, a series of complications can occur during the procedure that may puzzle endoscopists. There is no standard operating procedure for addressing these complications. The cases described in the current study can provide some reference for others.

Core tip: Tissue glue has been widely used in endoscopic gastric variceal obturation (EGVO) but there is little discussion on procedure-related complications. In our study, the procedure-related complications in 628 EGVO procedures with tissue glue were retrospectively analyzed. These complications include sticking of the needle to the varix, glue adhesion to the endoscope, blockage of the catheter, and sticking of the ligation device to the esophageal varices in the subsequent endoscopic variceal ligation. Although these complications were rare, they may be fatal and always puzzle the endoscopists. Besides incidence, how to tackle and prevent these complications were discussed in the current study.

- Citation: Guo YW, Miao HB, Wen ZF, Xuan JY, Zhou HX. Procedure-related complications in gastric variceal obturation with tissue glue. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(43): 7746-7755

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i43/7746.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i43.7746

Esophageal varices (EV) and gastric varices (GV) are pathological portosystemic shunts that often occur in patients with portal hypertension (PH). Compared with esophageal variceal hemorrhage, gastric variceal bleeding is more severe and has a higher mortality rate. Endoscopic gastric variceal obturation (EGVO) with the intravariceal injection of tissue glue has become the first choice for the treatment of gastric variceal hemorrhage and is one of the most important therapies in the treatment of GV in many countries, including China[1-11].

Although EGVO is usually safe and effective, a series of complications can occur, some of which are fatal. Post-endoscopic treatment complications such as abdominal pain, pyrexia, organ embolization and local ulceration have been widely reported and discussed, but the incidence of procedure-related complications was calculated in only some studies and was not thoroughly analyzed[12-16]. Most of the procedure-related complications were only described as case reports. These complications include sticking of the needle to the varix, glue adhesion to the endoscope resulting in difficulty withdrawing the endoscope, blockage of the catheter during the injection, and more seriously, sticking of the ligation device to the esophageal varices in the subsequent endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL). Although these complications were rare, they may be fatal and always puzzle operators, especially those in training. In the current study, we focus on procedure-related complications, evaluate their incidence, analyze the reasons and discuss the solutions.

Overall, 628 EGVO procedures were performed in 519 patients in the Department of Endoscopy of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University from January 2011 to December 2016. The 519 patients underwent at least one EGVO. A total of 82 patients underwent repeated EGVO 1-3 times in the subsequent sequential endoscopic therapy for esophageal and gastric varices. The clinical data of patients and procedure-related complications of EGVO were retrospectively analyzed. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University.

In our Department of endoscopy, patients with esophageal and gastric varices, most of whom have a history of variceal hemorrhage, undergo a sequence of endoscopic treatments unless there were endoscopic contraindications or more suitable for transjugular intrahepatic porto-system stent shunt (TIPSS) and surgery, including EGVO approximately 1-2 times and EVL 3-5 times, sometimes followed by endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy 1-2 times on smaller esophageal varices that were not suitable for EVL. The interval between the two procedures was approximately 4 wk until the varices were eradicated or considerably alleviated. We performed the treatment mainly according to Baveno Consensus[17,18] and United Kingdom guidelines on the management of variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotic patients[19].

The endoscopes used for glue injection were all Olympus (Japan), including GIF-H260 and GIF-H290. Injection catheters (Olympus Japan) with 21 or 23G needles and a 6 mm long needle tip were used. The tissue glue was N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBC). There were two brands of NBC used in our department: Histoacryl (German) and Compant (SMR China). All injections were performed by the same medical team.

Complete endoscopic reports were obtained in 473 out of 628 EVGO procedures and included the detailed injection methods written by endoscopists. The detailed injection methods were not written by endoscopists in the remaining 155 EVGO procedures. In the 473 EVGO procedures, 263 procedures were performed using the classical “sandwich” injection with lipiodol-diluted NBC[20], 159 procedures were performed with undiluted NBC, and the remaining 51 procedures were performed using other modified “sandwich” injections. The endoscope tip and channel were protected by simethicone.

In the classical “sandwich” injection, the injection order was lipiodol, lipiodol-diluted NBC, and then lipiodol. The injection catheter was pre-filled with 1.0-1.2 mL of lipiodol. NBC was diluted with lipiodol at a ratio of 0.5:0.8 to 0.5:0.5. The target varix was located and punctured with the needle, and the lipiodol-diluted NBC was pushed into the varix followed by another 1.0-1.2 mL of lipiodol flush. The needle was quickly withdrawn into the catheter and removed from the varix.

After 2013, all brands of lipiodol in China required a complicated sensitivity test before use, and nearly all of them were forbidden to be used for intravascular injection. Therefore, the lipiodol- lipiodol-diluted NBC-lipiodol method is inconvenient, especially for emergent patients. Several modified “sandwich” methods were attempted. Undiluted NBC must be used as a working solution. The solution used for the pre-fill catheter included 50% glucose, sterile saline, distilled water, and 1% aethoxysklerol. Flush water used after the working solution injection included 50% glucose, distilled water and sterile saline.

Statistical data were expressed as mean ± SD or as a percentage. A χ2 test was used to compare the constituent ratio of non-continuous variables between the two groups. A statistical significance threshold of P = 0.05 was adopted.

In the 519 patients, HBV cirrhosis was the most cause of gastric varices and the most common type of gastric varices was gastroesophageal varices 1 (GOV1) + GOV2. Most of the patients had a liver function of Child-Pugh A or Child-Pugh B (Table 1).

| Clinical features | n (%) |

| Total number of patients | 519 |

| Male | 392 (75.5) |

| Female | 127 (24.5) |

| Mean age (yr) | 47.9 ± 10.8 |

| Etiology of gastric varices | |

| HBV cirrhosis | 386 (74.3) |

| HCV cirrhosis | 21 (4.0) |

| Alcoholism cirrhosis | 18 (3.5) |

| Combined cirrhosis | 19 (3.7) |

| Cryptogenic cirrhosis | 29 (5.6) |

| Others (PBC, Budd-Chiari syndrome, PVT, etc.) | 46 (8.9) |

| Classification of gastric varices | |

| GOV1 | 53 (10.2) |

| GOV2 | 153 (29.5) |

| GOV1 + GOV2 | 304 (58.6) |

| IGV1 | 7 (1.3) |

| IGV2 | 2 (0.4) |

| Child-Pugh classification | |

| A | 195 (37.6) |

| B | 231 (44.5) |

| C | 93 (17.9) |

In the 628 EGVO procedures, the most common procedure-related complications was blockage of the injection catheter just when the glue was being injected, the very rare but intractable complications were glue adhesion to the endoscope resulted in difficulty withdrawing the endoscope and ligation device sticking to the varices (Table 2).

| Complications | n (%) |

| Total number of EGVO procedures | 628 |

| Sticking of the needle to the varix | 9 (1.43) |

| Blockage of the injection catheter | 17 (2.71) |

| Glue adhesion to the endoscope resulted in difficulty withdrawing the endoscope | 1 (0.159) |

| Ligation device sticking to the varices | 2 (0.318) |

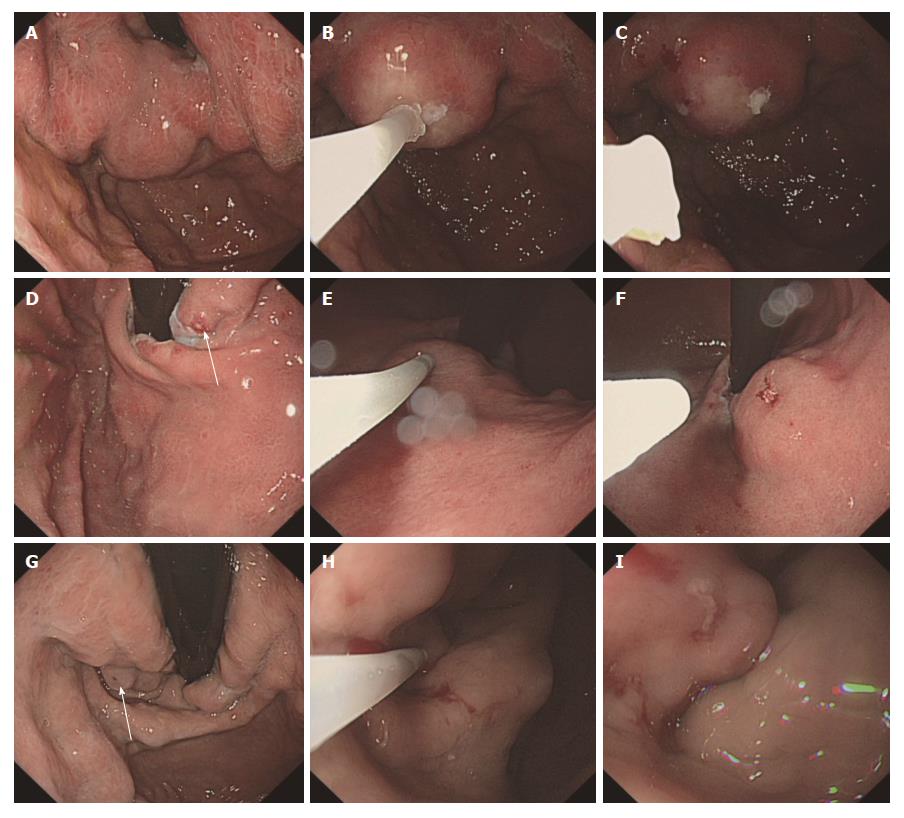

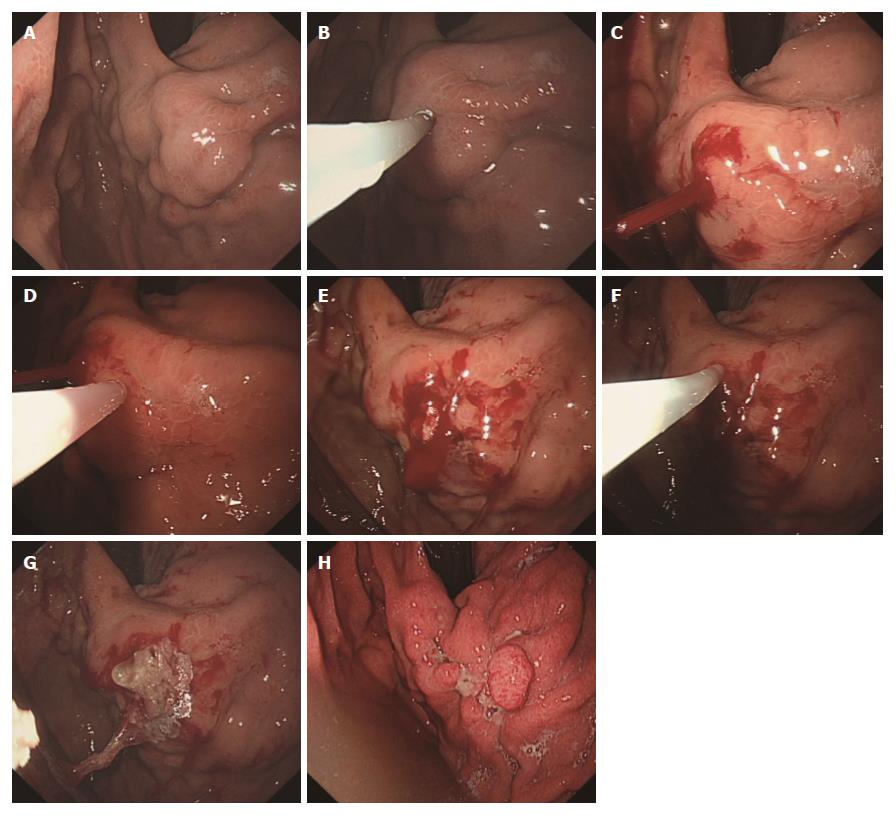

In the 628 EGVO procedures, sticking of the needle to the varix occurred in 9 cases (1.43%). Among the 9 cases, 1 case out of 263 procedures (0.843%) involved the use of NBC diluted with lipiodol, and 8 out of 159 procedures (5.03%) involved the use of undiluted NBC (χ2 = 23.202, P = 0.000). Among the 9 cases, 2 cases had a liver function of Child-Pugh A, 4 cases had a liver function of Child-Pugh B and 3 cases had a liver function of Child-Pugh C. There was no statistical difference of the complication among the patients with liver function of Child-Pugh A, B and C (χ2 = 0.927, P = 0.629). Once the sticking of the needle to the varix was noted, the tip of the endoscope was rapidly drawn near the varix without hesitation and then directly withdrawn along the direction of the needle that was inserted inserting the varix as soon as possible. In 7 of 9 cases of needle sticking, the needle was successfully withdrawn with no bleeding or errhysis but could stop on its own (Figure 1). Persistent dropwise bleeding was observed in one patient and another NBC injection was needed to stop the bleeding. In one case, blockage of the catheter during injection and sticking of the needle to the varix occurred at the same time. A large spurt bleeding occurred, and two other injections of undiluted NBC with a total volume of 4 mL were performed immediately and hemostasis was achieved (Figure 2). The patient had an increase in heart rate but not a drop in blood pressure. Somatostatin was administered to prevent rebleeding. The patient finished the sequence therapy of esophageal and gastric varices in the following 6 mo.

If several gastric varices needed to be obliterated in one procedure, blockage of the injection catheter was common during the whole procedure and several injection catheters were needed. However, it was relatively rare that the catheter became blocked just when the glue was being injected. In the 628 EGVO procedures, the catheter became blocked in 17 cases (2.71%) during the injection. Four cases also included the needle sticking to the varix. Rapid withdrawal and change of the injection catheter was the only option for a simple injection catheter obstruction. Bleeding from the injection position, such as errhysis, dropwise bleeding and even spurt could be observed in many cases. Unlike the needle sticking to the varix, the pin pole was small, and the bleeding caused by simply withdrawing the needle was not usually massive. Another rapid injection of NBC could solve the problem. Maintenance of clear vision and skillful and efficient assistance were important.

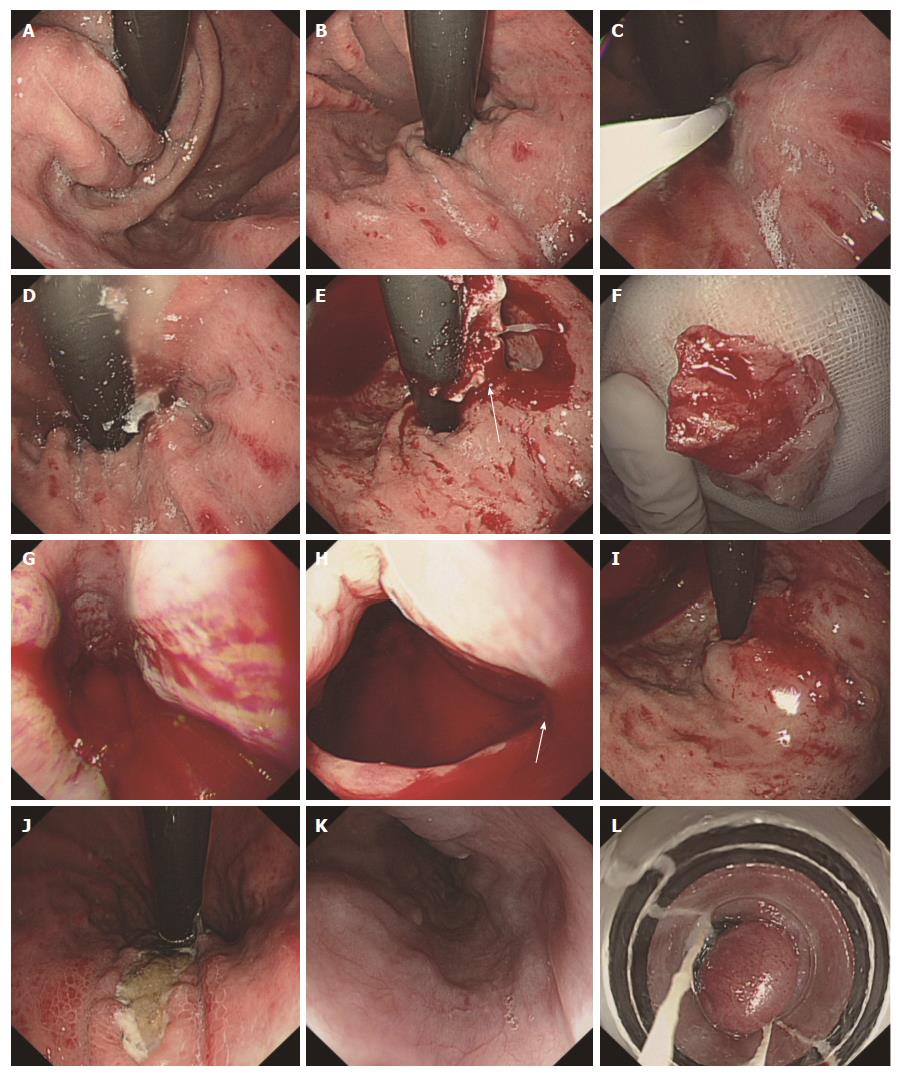

Despite the protection of the endoscopic tip by simethicone, the glue would sometimes adhere to the endoscope. Most endoscopists did not record this event in their endoscopic reports, because the endoscope could be withdrawn smoothly so long as the adhesion was noted in time and the glue adherence was minimal. Acetone was used for the removal of the adhesion glue. In one case, a large amount of glue had adhered to the surface of endoscope. The endoscopist did not note or address this issue the first time. When two injections of NBC were completed on the same varix, a large mass of solidified glue was discovered but had become too hard. Biopsy forceps and foreign body forceps were used to try to remove the glue from endoscope, but both failed. The patient had a liver function of Child C and the surgery was difficult. Finally, the endoscope had to be withdrawn very slowly with the adhesive glue. The glue was 1.5 cm in width and 3.0 cm in length. Another endoscope was immediately inserted. A large area of mucous was damaged in the esophagus and gastric cardia and bleeding was observed in multiple places. An injection of 1% aethoxysklerol was used to stop the bleeding at several severe points (Figure 3). The patient achieved hemostasis when treated with somatostatin and blood transfusion and underwent EVL 5 wk later.

The sticking of the ligation device to the varices was extremely rare in the treatment of esophageal and gastric varices via endoscopy. It occurred in two cases, when the patients underwent EVL after EGVO during the same procedure or 4 wk later. Some of the glue injected into the gastric varices would extend to the esophageal varices along the blood flow. In one case, the patient underwent EVL immediately after EGVO. When the esophageal varices were sucked by ligation device, the glue leaked from the varices and stuck to the ligation device. The ligation device was successfully separated from the esophageal varix after the release of all bands and no persistent bleeding occurred. In another case[21], the patient underwent EVL 3 times after EGVO. The first and second EVL both went well. The patient underwent the third EVL at 4 mo after EGVO. When the varix was sucked by ligation device, the variceal bulb containing the glue was embedded in the cavity of the transparent cap and could not be released. The laceration of the vein and massive bleeding were observed. The bleeding ceased after 10 mL of 1% aethoxysklerol were injected with the aid of the transparent cap.

Unlike other reports, the current study mainly focused on the analysis of the complications that occur during the EGVO procedure that puzzle operators, especially beginners. The tissue glue, also called tissue adhesive, that is primarily used in gastric variceal obliteration is N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBC). NBC will solidify within 10-15 s once it contacts the hydroxyl ions present in plasma. When it is used in variceal obturation, a smooth and skillful operation is important to prevent procedure-related complications. The instrument, different methods of injection, and different working solutions also affect the outcome of treatment.

It had been reported that the use of undiluted glue might contribute to the impaction of the needle tip in the varices and appeared to relate to blockage of the injection catheter. The present study also revealed that the sticking of the needle to the varices occurred more easily with an undiluted glue injection[22-24]. The use of lipiodol-diluted NBC can delay solidification and enable radiographic visualization but might increase the chances of distal embolization. In contrast, undiluted NBC solidifies more quickly, but distal embolization seems less[20,25-27]. When the diluted glue was used, most of the endoscopists in our department preferred to keep the needle in the target varix for 5-10 s after the injection; thus, the full solidification could avoid a spurt or dropwise bleeding from the injection site. When performing an injection with undiluted glue, it is wise to withdraw the catheter rapidly once the injection is completed, which could avoid some cases of needle sticking. The speed of injection by the assistant is also important; an injection that is too slow might result in blockage of the injection catheter or the needle sticking to the varices, and an injection that is too fast might contribute to the complication of distal embolism[28]. The use of an injector with a 21G needle rather than a 23G needle appears not to easily cause blockage of the injector. In the current study, in some cases that EGVO was performed with undiluted glue, the injector with a 21G needle was used, the endoscopist withdrew the catheter soon after injection, and the speed of the injection was not slow; however, sticking of needle to the varices and blockage of the injection catheter still occurred. We considered other risk factors. In some of our procedures and in other reported studies, sterile saline was used to flush the catheter to measure or prefill the dead space. In our observation, solidification would occur after NBC was mixed with saline in vitro, so flushing the catheter with distilled water is a better choice. In China, some endoscopists prefer to inject a certain volume of 1% aethoxysklerol before the injection of the glue to decrease the volume of glue and glue-related complications in the treatment of large gastric varices. However, we observed that the glue would solidify very soon after mixing with 1% aethoxysklerol in vitro, suggesting it might be a risk factor for blockage of the catheter. The 50% glucose and 5% glucose solutions would not solidify after mixing with glue in vitro and are both safe for flushing the catheter.

What to do once the needle sticks to the varices? Some experts suggest that the needle can be kept in the varices for several minutes until the glue is hard enough. Then, the endoscopic tip of the varices can be closed, the varices can be pressed slightly, and the needle can be withdrawn. However, no one can guarantee that the needle would stick more tightly to the varices while waiting, and when the endoscopic tip presses the varices, the view is not clear, and the endoscopic tip may also stick to the varices. In the current study, once the sticking of the needle to the varix was noted, the tip of the endoscope was rapidly drawn near the varix, but did not touch, and then was directly withdrawn along the direction of needle that was inserted into the varix as soon as possible. The solidification of the glue was incomplete at that time, and the needle could be withdrawn relatively easily. In 7 of 9 cases of needle sticking, the needle was successfully withdrawn. One case needed another injection of glue, but the bleeding was not massive. One patient with Child C liver function and large gastric varices was unfortunate. Sticking of the needle and blockage of the catheter occurred at the same time, and there was massive bleeding from the injection site. Although hemostasis was finally achieved, it could have been fatal[22-24]. In some experts’ experience, if the needle is too difficult to withdraw, the needle should remain in the varices, and TIPPS or surgery should be performed. In case of uncontrolled bleeding, TIPPS or surgery is also needed[10]. However, there is no a standard method for how to address the sticking needle; each method could lead to massive bleeding or a fatal outcome.

The protection of the endoscopic tip by simethicone, lipiodol or another oil-based contrast agents and the performance of a careful operation can noticeably decrease the incidence of glue adhesion to the endoscope[10,25]. Most of the time, timely observation and rapid withdraw of the endoscope always works because a small amount of glue has adhered to the endoscope and the adhesion is loose at the beginning. If a large amount of glue has adhered to the endoscope and the adhesion was not noted in time, it is very difficult to manage because there is an increased chance of multiple sites of laceration of varices when the endoscope is withdrawn. An injection of 1% aethoxysklerol or other sclerosants can be used to control acute bleeding, especially when the accurate bleeding position is difficult to locate and clear vision cannot be obtained. Sclerosants can be injected either intravariceally or paravariceally. These types of injection can be managed more easily and quickly compared with EVL and EGVO and do not require a second oral intubation[29]. Thus, precious time is gained for patients, and further treatments can be considered. Sometimes, TIPPS and surgery are needed.

EVL is usually performed after EGVO during the same procedure or after a period of time[18,19]. The glue that is injected into the gastric varices usually extends to the esophageal varices along the blood flow. Ligation device sticking to the esophageal varices is extremely rare. No report about this complication was found. First, it is wise to avoid the ligation of a varix with a tissue glue plug. When the varices are sucked by the ligation device with a negative pressure and ligated with a band, some ruptures at the site of ligation, and bleeding from the rupture can occur. This kind of bleeding is usually small and can spontaneously stop. However, if the varices contain some glue that did not fully solidify, the glue would be pressed out and stick to the ligation. Usually, we can compress a varix with the tip of the ligation device or suck the varix gently with a lower suction pressure. If the varix is hard and difficult to suction, the varix may contain glue, and ligation on this site should be abandoned. If the ligation device sticks to a varix, some actions can be tried, such as releasing all bands and cutting the string from the handle, flushing the ligation site with air and water, and even more surgery. If laceration occurs, it would be fatal. We have little experience addressing this situation, and it merits more discussion. Since endoscopic ultrasound-guided NBC injection has been successfully applied in clinical practice[30-32], it may be used in the identification of varices that contain glue.

In conclusion, to avoid procedure-related complications, comprehensive preparation, careful and skillful operation, and smooth assistance are very important. There is currently no standard operating procedure for addressing these complications. We hope that the cases described in the current study can provide some reference for others.

Tissue glue has been widely used in endoscopic gastric variceal obturation (EGVO). Although EGVO is usually safe and effective, a series of complications can occur. Post-endoscopic treatment complications have been widely reported and discussed, but there is little in-depth discussion on procedure-related complications. The complications associated with tissue glue that occur during gastric variceal obturation were retrospectively evaluated in the current study.

Post-endoscopic treatment complications of EGVO such as abdominal pain, pyrexia, organ embolization and local ulceration have been widely reported and discussed, but the incidence of procedure-related complications was calculated in only some studies and was not thoroughly analyzed. Most of the procedure-related complications were only described as case reports. In the current study, the authors focused on procedure-related complications, evaluated their incidence, analyzed the reasons and discuss the solutions. The authors hope that the cases described in the current study can provide some reference for others.

The main objectives of the current study was to evaluate four procedure-related complications of EGVO, including sticking of the needle to the varix, glue adhesion to the endoscope resulting in difficulty withdrawing the endoscope, blockage of the catheter during the injection, and more seriously, sticking of the ligation device to the esophageal varices in the subsequent endoscopic variceal ligation. Investigation of the incidence, reasons and solutions of these complications is expected to help the endoscopists especially those in training to avoid some troubles.

Six hundred and twenty-eight EGVO procedures (case-times) with tissue glue were performed in 519 patients in the Department of Endoscopy of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University from January 2011 to December 2016. The tissue glue used in EGVO was N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBC). The endoscopic reports and medical records of all patients were collected. The clinical data of patients and procedure-related complications of EGVO were retrospectively analyzed.

In the 519 patients, HBV cirrhosis was the most cause of gastric varices (75.5%) and the most common type of gastric varices was GOV1 + GOV2 (58.6%). Most of the patients had a liver function of Child-Pugh A (37.6%) or Child-Pugh B (44.5%). Detailed injection methods were written by endoscopists in 473 out of 628 EVGO procedures, including 263 procedures that were performed using the classical “sandwich” injection with lipiodol-diluted NBC, 159 procedures that were performed with undiluted NBC, and the remaining 51 procedures that were performed using other modified “sandwich” injections. In the 628 EGVO procedures, sticking of the needle to the varix occurred in 9 cases (1.43%), including 1 case that used lipiodol-diluted NBC and 8 cases that used undiluted NBC (P = 0.000). There was no statistical difference of the complication among the patients with liver function of Child-Pugh A, B and C (P = 0.629). The needle was successfully withdrawn in 8 cases. Large spurt bleeding occurred in one case, and hemostasis was achieved by two other injections of undiluted glue. The injection catheter became blocked in 17 cases (2.71%) just during the injection, and 4 cases were complicated with the needle sticking to the varix. Large glue adhesion to the endoscope resulted in difficulty withdrawing the endoscope in 1 case. Bleeding from multiple sites was observed in the esophagus and gastric cardia after the endoscope was withdrawn. Hemostasis was achieved by 1% aethoxysklerol injection and intravenous somatostatin. The ligation device stuck to the varices in two cases during the subsequent endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL). In one case, the ligation device was successfully separated from the esophageal varix after all bands were released. In another case, a laceration of the vein and massive bleeding were observed. The bleeding ceased after 1% aethoxysklerol injection.

The findings of this study verified that procedure-related complications were rare but sometimes were extremely dangerous. There is currently no standard operating procedure for addressing these complications. To avoid procedure-related complications, comprehensive preparation, careful and skillful operation, and smooth assistance are very important.

Although EGVO with tissue glue is usually safe and effective, a series of complications can occur during the procedure. Some factors might influence the occurrence of the complications and their outcomes, including Child-Pugh Class, type of gastric varices (GOV1, GOV2, IGV1 and IGV2), platelets, INR, volume of tissue glue using during EGVO, and diameter of the injection needle. These factors were not fully investigated and discussed in the current retrospective study. A well designed prospective study with a large sample is expected to solve that problem.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Cui J, Keyashian K, Vujasinovic M S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Mosli MH, Aljudaibi B, Almadi M, Marotta P. The safety and efficacy of gastric fundal variceal obliteration using N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate; the experience of a single canadian tertiary care centre. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:152-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kozieł S, Kobryń K, Paluszkiewicz R, Krawczyk M, Wróblewski T. Endoscopic treatment of gastric varices bleeding with the use of n-butyl-2 cyanoacrylate. Prz Gastroenterol. 2015;10:239-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cipolletta L, Zambelli A, Bianco MA, De Grazia F, Meucci C, Lupinacci G, Salerno R, Piscopo R, Marmo R, Orsini L. Acrylate glue injection for acutely bleeding oesophageal varices: A prospective cohort study. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:729-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Saraswat VA, Verma A. Gluing gastric varices in 2012: lessons learnt over 25 years. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2012;2:55-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kang EJ, Jeong SW, Jang JY, Cho JY, Lee SH, Kim HG, Kim SG, Kim YS, Cheon YK, Cho YD. Long-term result of endoscopic Histoacryl (N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate) injection for treatment of gastric varices. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1494-1500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Triantafyllou M, Stanley AJ. Update on gastric varices. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:168-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Khawaja A, Sonawalla AA, Somani SF, Abid S. Management of bleeding gastric varices: a single session of histoacryl injection may be sufficient. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:661-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Monsanto P, Almeida N, Rosa A, Maçôas F, Lérias C, Portela F, Amaro P, Ferreira M, Gouveia H, Sofia C. Endoscopic treatment of bleeding gastric varices with histoacryl (N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate): a South European single center experience. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2013;32:227-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Choudhuri G, Chetri K, Bhat G, Alexander G, Das K, Ghoshal UC, Das K, Chandra P. Long-term efficacy and safety of N-butylcyanoacrylate in endoscopic treatment of gastric varices. Trop Gastroenterol. 2010;31:155-164. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Al-Ali J, Pawlowska M, Coss A, Svarta S, Byrne M, Enns R. Endoscopic management of gastric variceal bleeding with cyanoacrylate glue injection: safety and efficacy in a Canadian population. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24:593-596. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Chang YJ, Park JJ, Joo MK, Lee BJ, Yun JW, Yoon DW, Kim JH, Yeon JE, Kim JS, Byun KS. Long-term outcomes of prophylactic endoscopic histoacryl injection for gastric varices with a high risk of bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2391-2397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cheng LF, Wang ZQ, Li CZ, Lin W, Yeo AE, Jin B. Low incidence of complications from endoscopic gastric variceal obturation with butyl cyanoacrylate. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:760-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jun CH, Kim KR, Yoon JH, Koh HR, Choi WS, Cho KM, Lim SU, Park CH, Joo YE, Kim HS. Clinical outcomes of gastric variceal obliteration using N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate in patients with acute gastric variceal hemorrhage. Korean J Intern Med. 2014;29:437-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Prachayakul V, Aswakul P, Chantarojanasiri T, Leelakusolvong S. Factors influencing clinical outcomes of Histoacryl® glue injection-treated gastric variceal hemorrhage. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2379-2387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ni Z, Chen H, Tang S, Zeng W, Xu H. The Efficacy and the Safety of Prophylactic N-Butyl-2-Cyanoacrylate Injection for Gastric Varices Using a Modified Injection Technique. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2016;26:e85-e90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fry LC, Neumann H, Olano C, Malfertheiner P, Mönkemüller K. Efficacy, complications and clinical outcomes of endoscopic sclerotherapy with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate for bleeding gastric varices. Dig Dis. 2008;26:300-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | de Franchis R; Baveno V Faculty. Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2010;53:762-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1066] [Cited by in RCA: 1030] [Article Influence: 68.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | de Franchis R; Baveno VI Faculty. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: Stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2015;63:743-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2011] [Cited by in RCA: 2291] [Article Influence: 229.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 19. | Tripathi D, Stanley AJ, Hayes PC, Patch D, Millson C, Mehrzad H, Austin A, Ferguson JW, Olliff SP, Hudson M. U.K. guidelines on the management of variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. Gut. 2015;64:1680-1704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 454] [Cited by in RCA: 415] [Article Influence: 41.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 20. | Seewald S, Ang TL, Imazu H, Naga M, Omar S, Groth S, Seitz U, Zhong Y, Thonke F, Soehendra N. A standardized injection technique and regimen ensures success and safety of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection for the treatment of gastric fundal varices (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:447-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wei XQ, Gu HY, Wu ZE, Miao HB, Wang PQ, Wen ZF, Wu B. Endoscopic variceal ligation caused massive bleeding due to laceration of an esophageal varicose vein with tissue glue emboli. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:15937-15940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | D’Imperio N, Piemontese A, Baroncini D, Billi P, Borioni D, Dal Monte PP, Borrello P. Evaluation of undiluted N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate in the endoscopic treatment of upper gastrointestinal tract varices. Endoscopy. 1996;28:239-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dhiman RK, Chawla Y, Taneja S, Biswas R, Sharma TR, Dilawari JB. Endoscopic sclerotherapy of gastric variceal bleeding with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:222-227. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Seewald S, Sriram PV, Naga M, Fennerty MB, Boyer J, Oberti F, Soehendra N. Cyanoacrylate glue in gastric variceal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2002;34:926-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Wang YM, Cheng LF, Li N, Wu K, Zhai JS, Wang YW. Study of glue extrusion after endoscopic N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection on gastric variceal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4945-4951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kumar A, Singh S, Madan K, Garg PK, Acharya SK. Undiluted N-butyl cyanoacrylate is safe and effective for gastric variceal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:721-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sato T, Yamazaki K. Evaluation of therapeutic effects and serious complications following endoscopic obliterative therapy with Histoacryl. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2010;3:91-95. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Marion-Audibert AM, Schoeffler M, Wallet F, Duperret S, Mabrut JY, Bancel B, Pere-Verge D, Wander L, Souquet JC. Acute fatal pulmonary embolism during cyanoacrylate injection in gastric varices. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008;32:926-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Poza Cordon J, Froilan Torres C, Burgos García A, Gea Rodriguez F, Suárez de Parga JM. Endoscopic management of esophageal varices. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:312-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 30. | Tang RS, Teoh AY, Lau JY. EUS-guided cyanoacrylate injection for treatment of endoscopically obscured bleeding gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:1032-1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Fujii-Lau LL, Law R, Wong Kee Song LM, Gostout CJ, Kamath PS, Levy MJ. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided coil injection therapy of esophagogastric and ectopic varices. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:1396-1404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Gubler C, Bauerfeind P. Safe and successful endoscopic initial treatment and long-term eradication of gastric varices by endoscopic ultrasound-guided Histoacryl (N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate) injection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:1136-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |