Published online Jan 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i4.723

Peer-review started: September 21, 2016

First decision: October 20, 2016

Revised: November 13, 2016

Accepted: December 2, 2016

Article in press: December 2, 2016

Published online: January 28, 2017

Processing time: 120 Days and 19 Hours

To investigate the long-term prognosis in peptic ulcer patients continuing taking antithrombotics after ulcer bleeding, and to determine the risk factors that influence the prognosis.

All clinical data of peptic ulcer patients treated from January 1, 2009 to January 1, 2014 were retrospectively collected and analyzed. Patients were divided into either a continuing group to continue taking antithrombotic drugs after ulcer bleeding or a discontinuing group to discontinue antithrombotic drugs. The primary outcome of follow-up in peptic ulcer bleeding patients was recurrent bleeding, and secondary outcome was death or acute cardiovascular disease occurrence. The final date of follow-up was December 31, 2014. Basic demographic data, complications, and disease classifications were analyzed and compared by t- or χ2-test. The number of patients that achieved various outcomes was counted and analyzed statistically. A survival curve was drawn using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the difference was compared using the log-rank test. COX regression multivariate analysis was applied to analyze risk factors for the prognosis of peptic ulcer patients.

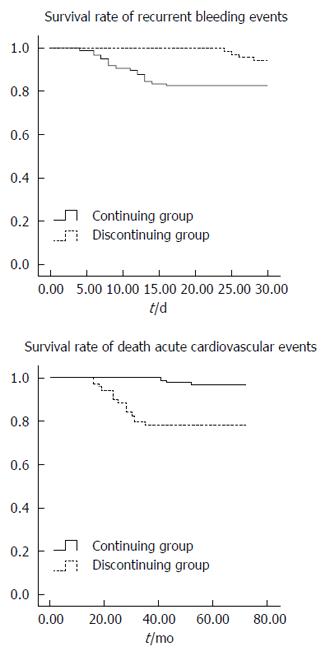

A total of 167 patients were enrolled into this study. As for the baseline information, differences in age, smoking, alcohol abuse, and acute cardiovascular diseases were statistically significant between the continuing and discontinuing groups (70.8 ± 11.4 vs 62.4 ± 12.0, P < 0.001; 8 (8.2%) vs 15 (21.7%), P < 0.05; 65 (66.3%) vs 13 (18.8%), P < 0.001). At the end of the study, 18 patients had recurrent bleeding and three patients died or had acute cardiovascular disease in the continuing group, while four patients had recurrent bleeding and 15 patients died or had acute cardiovascular disease in the discontinuing group. The differences in these results were statistically significant (P = 0.022, P = 0.000). The Kaplan-Meier survival curve indicated that the incidence of recurrent bleeding was higher in patients in the continuing group, and the risk of death and developing acute cardiovascular disease was higher in patients in the discontinuing group (log-rank test, P = 0.000 for both). Furthermore, COX regression multivariate analysis revealed that the hazard ratio (HR) for recurrent bleeding was 2.986 (95%CI: 067-8.356, P = 0.015) in the continuing group, while HR for death or acute cardiovascular disease was 5.216 (95%CI: 1.035-26.278, P = 0.028).

After the occurrence of peptic ulcer bleeding, continuing antithrombotics increases the risk of recurrent bleeding events, while discontinuing antithrombotics would increase the risk of death and developing cardiovascular disease. This suggests that clinicians should comprehensively consider the use of antithrombotics after peptic ulcer bleeding.

Core tip: Patients with peptic ulcer bleeding were enrolled into our study, and clinical information was analyzed by statistical method. We found that continuing antithrombotic drugs for peptic ulcer patients increased the risk of recurrent bleeding events, and discontinuing antithrombotic drugs increased the risk of death or cardiovascular events. Our results indicate that clinicians should balance the usage of antithrombotics to reduce the risk of peptic ulcer bleeding.

- Citation: Wang XX, Dong B, Hong B, Gong YQ, Wang W, Wang J, Zhou ZY, Jiang WJ. Long-term prognosis in patients continuing taking antithrombotics after peptic ulcer bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(4): 723-729

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i4/723.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i4.723

Peptic ulcer is a highly prevalent illness[1], and it tremendously threatens the health of humans due to high morbidity and severe complications[2-5]. Among all complications, peptic ulcer bleeding is one of the common clinical diseases[6]. In recent years, despite the application of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)[7-9] and Helicobacter pylori eradication[10-12], the morbidity of peptic ulcer bleeding has not decreased[13] at least partially due to the use of antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, and thrombin inhibitors. These drugs have recently been used extensively for the treatment of thromboembolic disease[14-16]. It has also been estimated that the usage of these drugs has been increasing worldwide as cardiovascular morbidity increases in the aged population[17,18]. This would induce a high incidence of peptic ulcer bleeding[19,20]. Aspirin is an antithrombotic drug that has been widely applied in view of the benefit in preventing cardiovascular disease[21,22]. However, patients with cardiovascular disease are recommended to immediately discontinue the usage of aspirin after successful endoscopic treatment of peptic ulcer bleeding, in order to prevent death or acute disease occurrence, according to the Medication Guide[23]. In a randomized double-blind study, Sung et al[24] found that recurrent bleeding events due to the continued usage of aspirin severely influences the prognosis of patients. Therefore, there is a dilemma to the clinical usage of antithrombotic drugs. Furthermore, there are few studies on antithrombotics usage for treating peptic ulcer bleeding patients, and there is increasing concern on these patients. Hence, we collected the clinical data of patients with peptic ulcer bleeding treated at our hospital in recent five years, aiming to investigate the effect of continued administration of antithrombotic drugs and identify the risk factors for prognosis.

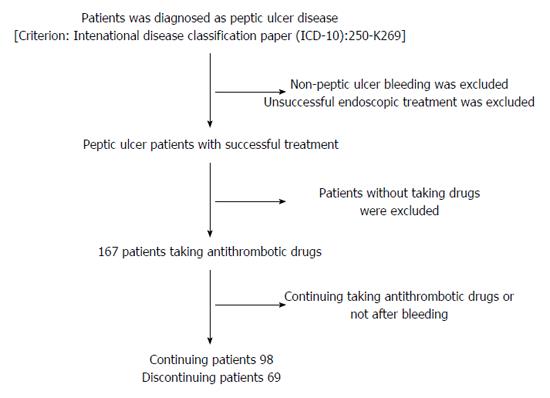

Patients with peptic ulcer treated at Tongren Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University from January 1, 2009 to January 1, 2014 were included in this study. The study ended on December 31, 2014. Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage was defined as hemoptysis, hematochezia, melena, fainting, or dizziness with anemia. The following patients were excluded: patients with non-peptic ulcer bleeding, esophageal varices, vascular dysplasia, esophageal or gastric cancer, and ulcer perforation; patients with peptic ulcer bleeding who had an unsuccessful endoscopic treatment; patients who did not receive antithrombotic drugs after a successful therapy; patients who received PIPs to prevent damage from antithrombotic drugs. The enrollment process is shown in Figure 1.

Finally, a total of 167 patients were enrolled in this study. Based on whether drug administration was continued or discontinued after peptic ulcer bleeding healed following endoscopic treatment, the patients were divided into either a continuing group (n = 98) or a discontinuing group (n = 69). The continuing group included the patients who continued taking the drugs after the bleeding healed, while the discontinuing group included the patients who discontinued taking the drugs after the bleeding healed. All patients in this study provided a signed informed consent form, and this study was approved by the hospital ethics committee.

The clinical data of the patients, including demographic data and complications, were analyzed statistically. The time to end point was strictly calculated. Primary end point was recurrent bleeding events within 30 d, including hemoptysis, melaena, > 2 g/dL of hemoglobin within 24 h, and unstable blood flow (systolic blood pressure ≤ 90 mmHg or heart rate ≥ 110 times/min). Patients with one of the aforementioned or combined characteristics were defined to achieve the primary end point. Secondary outcomes were death, acute cardiovascular disease, acute myocardial infarction, and ischemia or transient ischemia. The number of patients with different outcomes was counted, and the difference was compared statistically. Survival time was collected to draw the survival rate.

All data were analyzed using SPSS 19.0 software. Age, hemoglobin levels, and body mass index (BMI) measurements are expressed as mean ± SD. Categorical data are expressed as percentages. Measurement data following a normal distribution were compared by the t-test. Frequency data were compared by the χ2-test. Kaplan-Meier method was applied to calculate the survival rate and draw the survival curve. Differences were compared using the log-rank test. The multivariable COX proportional regression model was applied to analyze the risk factors for prognosis in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

After screening, a total of 167 patients with peptic ulcer bleeding were enrolled into this study. Among these patients, 98 continued receiving antithrombotic drugs, and 69 discontinued. The average age of the patients who continued and discontinued receiving antithrombotic drugs was 70.8 ± 11.4 years and 62.4 ± 12.0 years, respectively (P = 0.000). The percentage of patients with a history of smoking or alcohol abuse was significantly higher in the continuing group than in the discontinuing group (P = 0.012). Furthermore, the rate of cardiovascular complications was significantly higher in the continuing group (P = 0.000; Table 1).

| Characteristic | Continuing group | Discontinuing group | T/χ2 | P value |

| No. of patients | 98 | 69 | ||

| Demographic data | ||||

| Gender (male/%) | 68 (69.39) | 42 (60.87) | 1.307 | 0.253 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 70.8 ± 11.4 | 62.4 ± 12.0 | 4.588 | 0.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 21.4 ± 4.5 | 22.0 ± 4.2 | 0.872 | 0.385 |

| Complications | ||||

| Smoking and alcohol abuse | 8 (8.2) | 15 (21.7) | 6.284 | 0.012 |

| Diabetes | 32 (32.7) | 15 (21.7) | 2.385 | 0.123 |

| Hypertension | 71 (72.4) | 56 (81.2) | 1.338 | 0.247 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 23 (23.4) | 8 (11.6) | 3.777 | 0.052 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 10 (10.2) | 8 (11.6) | 0.081 | 0.775 |

| Acute cardiovascular disease | 65 (66.3) | 13 (18.8) | 36.681 | 0.000 |

| Non-antithrombotic drug usage | ||||

| Aspirin | 84 (85.7) | 59 (85.5) | 0.001 | 0.970 |

| Forrest classification | ||||

| I-II | 31 (31.6) | 28 (40.6) | 1.419 | 0.234 |

| III | 67 (68.4) | 41 (59.4) | 1.419 | 0.234 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.0 ± 2.4 | 8.6 ± 2.1 | 1.116 | 0.266 |

Recurrent bleeding occurred in 18 patients in the continuing group and in four patients in the discontinuing group. Death or acute cardiovascular disease occurred in three patients in the continuing group and in 15 patients in the discontinuing group. The differences in the rates of primary and secondary outcomes between the two groups were statistically significant (P = 0.018, P = 0.000; Table 2).

| Continuing group | Discontinuing group | χ2 | P value | |

| Recurrent ulcer bleeding events | 18 (18.4) | 4 (5.8) | 5.594 | 0.018 |

| Death or cardiovascular disease | 3 (3.1) | 15 (21.7) | 14.689 | 0.000 |

Kaplan-Meier results indicated that bleeding occurred more frequently in patients in the continuing group, while survival rate was significantly higher in patients in the discontinuing group (Log-rank test, P = 0.022, P = 0.000; Figure 2).

The multivariable COX proportional regression model indicated that continuing intake of antithrombotic drugs increased the risk of recurrent bleeding events (95%CI: 1.067-8.356, OR = 2.986, P = 0.015), while discontinuing intake of antithrombotic drugs increased the risk of death or acute cardiovascular disease (95%CI: 1.035-26.278, OR = 5.216, P = 0.028; Table 3).

| Recurrent ulcer bleeding events | Death or cardiovascular occurrence | |||||||

| β | OR | 95%CI | P value | β | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Usage of antithrombotics | 1.094 | 2.986 | 1.067-8.356 | 0.015 | 1.652 | 5.216 | 1.035-26.278 | 0.028 |

Peptic ulcer is one of the most common clinical gastrointestinal tract diseases at present[6,25], and it is generally induced by damage of the gastric or duodenal mucosa. Gastric acid and protease play a crucial role in disease progression[26,27]. The aged population accounts for most of the cases, and ulcer bleeding, perforation, and pyloric obstruction are the most common complications[28-31]. Helicobacter pylori infection, excessive secretion of gastric acid, and excessive antithrombotic drug intake often trigger the occurrence of ulcer bleeding[32-34]. In recent years, peptic ulcer morbidity increased slowly due to medical technology progression[35]; however, the incidence of ulcer bleeding has been continuously increasing[36,37].

Cardiovascular disease is defined as ischemic or hemorrhagic disease occurring in all tissues due to atherosclerosis and blood viscosity[38]. In view of its high morbidity and mortality, more and more people, even healthy people, tend to take antithrombotics to prevent and reduce its risk[39]. However, excessive drug usage will increase the risk of bleeding in patients with ulcer bleeding.

As the aged population has an increased necessity for preventing acute cardiovascular disease, aspirin and other antithrombotics continue to be broadly used[40-42]. It has been reported that most patients with established cardiovascular disease ignore the risk of aspirin, and continue to take aspirin or other antithrombotics for secondary prevention[43,44]. Even more, the literature has shown that cardiovascular disease complications occur more frequently in patients who have discontinued antiplatelet drug therapy, compared to patients who continue this therapy[45]. Nevertheless, continuing intake of aspirin or antithrombotic drugs will increase the risk of hemorrhage complications in surgery instead[46,47]. Accordingly, clinicians could not balance the risk of cardiovascular disease and hemorrhage complications. In addition, there are few studies on the prognosis of patients with peptic ulcer bleeding. Hence, the clinical data of patients with peptic ulcer bleeding treated at our hospital were collected and analyzed to discuss the prognosis of patients, hoping to provide guidance for clinical applications.

Our study revealed that patients were older in the continuing group than in the discontinuing group, indicating that aged patients need more antithrombotics. This is consistent to the current social situation. The number of patients with cardiovascular complications was higher in the continuing group than in the discontinuing group, which is in agreement with a previous report that patients with an established disease tend to continue taking drugs. In addition, there was a difference in smoking and alcohol abuse between the two groups; there were more of these patients in the discontinuing group. It is plausible that patients taking drugs tended to reduce smoking or alcohol consumption.

Our study indicated that patients who continued to take the drugs had a higher risk of recurrent bleeding events. In contrast, patients in the discontinuing group had a higher risk of death or acute cardiovascular disease. This result is inconsistent with recent studies reporting that there was no difference between the two groups. On one hand, our follow-up time did not have a limit. However, patients with less than two months of follow-up were excluded in the study conducted by Kim et al[48]. Furthermore, it has been widely accepted that recurrent bleeding time was shorter than normal bleeding time. On the other hand, the number of patients in these two studies is different. Consistent with our results, Sung et al[24] estimated a higher incidence of recurrent bleeding events in patients continuing taking aspirin in a randomized double-blind study (a likelihood ratio of nearly 2). Through retrospective research, we also obtained similar results (a likelihood ratio of nearly 3)[49], which further supports this view. This implies that more attention should be given when continuing taking antithrombotics.

This study has some limitations. First, a limited number of patients could not sufficiently support our conclusion. Second, we did not distinguish different antithrombotic drugs. However, many studies have shown that the single or combined application of drugs would result in an obvious difference. Finally, the definite time of bleeding was lacking. Hence, we were not able to obtain the precise time when to discontinue or continue drugs.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that after the occurrence of peptic ulcer bleeding, continuing the intake of drugs would increase the risk of recurrent bleeding events, while discontinuing the intake of drugs will increase the risk of death and acute cardiovascular occurrence. These indicate that clinicians must extensively weigh the benefits and risks when using antithromboticsin for treating patients with peptic ulcer bleeding.

Peptic ulcer is one of the most common gastrointestinal diseases which is generally induced by damage of the gastric or duodenal mucosa. Gastric acid and protease play a crucial role in disease progression. The aged population accounts for most of the cases, and ulcer bleeding, perforation, and pyloric obstruction are the most common complications. Helicobacter pylori infection, excessive secretion of gastric acid, and excessive antithrombotic drug taking would trigger the occurrence of ulcer bleeding. In recent years, peptic ulcer morbidity has increased slowly duo to medical technology progression, but ulcer bleeding incidence rate has been increasing all the time. Cardiovascular disease is defined as ischemic or hemorrhagic disease occurring in all tissues due to atherosclerosis and blood viscosity. In view of its high morbidity and mortality, more and more people, even healthy people, tend to take antithrombotics to prevent and reduce its risk. However, excessive drug usage will increase bleeding risk instead in ulcer bleeding patients.

As the aged population has an increased necessity for preventing acute cardiovascular disease, aspirin and other antithrombotics are broadly used. It is reported that most patients with established cardiovascular disease ignore the risk of aspirin and still insist in taking aspirin or other antithrombotics for secondary prevention. Even more, the literature shows that patients have cardiovascular disease complication more easily in those discontinuing antiplatelet drug therapy compared to those continuing antiplatelet drug therapy. Nevertheless, continuing aspirin or antithrombotic drugs will increase hemorrhage complication risk in surgery instead. Accordingly, clinicians could not balance risk of cardiovascular disease and hemorrhage complication.

The authors investigated the prognosis and risk factors in peptic ulcer bleeding patients. Even more, they showed two survival curves with disparate outcomes to demonstrate survival difference in patients continuing or discontinuing taking antithrombotics. These results suggest that clinicians must take more attention in the usage of antithrombotic drugs.

This study demonstrates that after occurrence of peptic ulcer bleeding, continuing taking drugs will increase the risk of recurrent bleeding events, and discontinuing drugs will increase risk of death and acute cardiovascular occurrence, which indicates that clinicians must weigh the risks and benefits when using antithrombotics to treat ulcer bleeding patients.

Patients with ulcer peptic bleeding were enrolled in this study and clinical information was analyzed by statistical method. Authors found that continuing antithrombotic drugs in ulcer peptic patients increased the risk of recurrent bleeding events while discontinuing drugs increased risk of death or cardiovascular events. The results indicated that clinicians should balance the usage of antithrombotics to reduce risk in peptic ulcer bleeding patients

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Higuchi K, Jung DH, Queiroz DM S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Chan FK, Leung WK. Peptic-ulcer disease. Lancet. 2002;360:933-941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Malmi H, Kautiainen H, Virta LJ, Färkkilä MA. Increased short- and long-term mortality in 8146 hospitalised peptic ulcer patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:234-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Muller MK, Wrann S, Widmer J, Klasen J, Weber M, Hahnloser D. Perforated Peptic Ulcer Repair: Factors Predicting Conversion in Laparoscopy and Postoperative Septic Complications. World J Surg. 2016;40:2186-2193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kefeli A, Basyigit S, Yeniova AO, Uzman M, Aktaş B. Retrograde Duodenoduodenal Intussusception: An Uncommon Complication of Peptic Ulcer. Chin Med J (Engl). 2015;128:2981-2982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bas G, Eryilmaz R, Okan I, Sahin M. Risk factors of morbidity and mortality in patients with perforated peptic ulcer. Acta Chir Belg. 2008;108:424-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Malfertheiner P, Chan FK, McColl KE. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. 2009;374:1449-1461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 618] [Cited by in RCA: 534] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Barkun AN. High-dose versus low-dose intravenous proton pump inhibitor treatment for bleeding peptic ulcers. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;6:675-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sung J. Proton Pump Inhibitor Management in Bleeding Peptic Ulcer Disease. Frontiers Gastrointest Res. 2013;32:68-76. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu N, Liu L, Zhang H, Gyawali PC, Zhang D, Yao L, Yang Y, Wu K, Ding J, Fan D. Effect of intravenous proton pump inhibitor regimens and timing of endoscopy on clinical outcomes of peptic ulcer bleeding. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1473-1479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jang EJ, Park SW, Park JS, Park SJ, Hahm KB, Paik SY, Sin MK, Lee ES, Oh SW, Park CY. The influence of the eradication of Helicobacter pylori on gastric ghrelin, appetite, and body mass index in patients with peptic ulcer disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23 Suppl 2:S278-S285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gisbert JP, Calvet X, Feu F, Bory F, Cosme A, Almela P, Santolaria S, Aznárez R, Castro M, Fernández N. M1112 Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for the Prevention of Peptic Ulcer Rebleeding. Long-Term Follow-up Study of 800 Patients. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:S334-S335. |

| 12. | Wong CS, Chia CF, Lee HC, Wei PL, Ma HP, Tsai SH, Wu CH, Tam KW. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for prevention of ulcer recurrence after simple closure of perforated peptic ulcer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Surg Res. 2013;182:219-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bardhan KD, Williamson M, Royston C, Lyon C. Admission rates for peptic ulcer in the trent region, UK, 1972--2000. changing pattern, a changing disease? Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:577-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mousa SA. Role of current and emerging antithrombotics in thrombosis and cancer. Drugs Today (Barc). 2006;42:331-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ryan J, Bolster F, Crosbie I, Kavanagh E. Antiplatelet medications and evolving antithrombotic medication. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42:753-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cheng JW, Vu H. Dabigatranetexilate: an oral direct thrombin inhibitor for the management of thromboembolic disorders. Clin Ther. 2012;34:766-787. |

| 17. | Pignone M, Anderson GK, Binns K, Tilson HH, Weisman SM. Aspirin use among adults aged 40 and older in the United States: results of a national survey. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:403-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Theocharis GJ, Thomopoulos KC, Sakellaropoulos G, Katsakoulis E, Nikolopoulou V. Changing trends in the epidemiology and clinical outcome of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a defined geographical area in Greece. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:128-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Loperfido S, Baldo V, Piovesana E, Bellina L, Rossi K, Groppo M, Caroli A, Dal Bò N, Monica F, Fabris L. Changing trends in acute upper-GI bleeding: a population-based study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:212-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Weil J, Langman MJ, Wainwright P, Lawson DH, Rawlins M, Logan RF, Brown TP, Vessey MP, Murphy M, Colin-Jones DG. Peptic ulcer bleeding: accessory risk factors and interactions with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gut. 2000;46:27-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Schwartz DJ. Aspirin in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2751-2752; author reply 2751-2752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Berger JS, Lala A, Krantz MJ, Baker GS, Hiatt WR. Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular events in patients without clinical cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am Heart J. 2011;162:115-124.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Laine L, Jensen DM. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:345-360; quiz 361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Sung JJ, Lau JY, Ching JY, Wu JC, Lee YT, Chiu PW, Leung VK, Wong VW, Chan FK. Continuation of low-dose aspirin therapy in peptic ulcer bleeding: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Caselli M, Alvisi V. Helicobacter pylori and peptic-ulcer disease. Lancet. 2002;359:1943-1944; author reply 1944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Højgaard L, Mertz Nielsen A, Rune SJ. Peptic ulcer pathophysiology: acid, bicarbonate, and mucosal function. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1996;216:10-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yeomans ND. The ulcer sleuths: The search for the cause of peptic ulcers. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26 Suppl 1:35-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Iwaya Y, Akamatsu T, Ito T, Nagaya T, Suga T, Arakura N. [Differential diagnosis of gastric ulcer and gastric cancer in elderly patients]. Nihon Rinsho. 2010;68:2036-2039. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Aabakken L. Current endoscopic and pharmacological therapy of peptic ulcer bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:243-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Noguiera C, Silva AS, Santos JN, Silva AG, Ferreira J, Matos E, Vilaça H. Perforated peptic ulcer: main factors of morbidity and mortality. World J Surg. 2003;27:782-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Moody FG, Cornell GN, Beal JM. Pyloric obstruction complicating peptic ulcer. Arch Surg. 1962;84:462-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Huang TC, Lee CL. Diagnosis, treatment, and outcome in patients with bleeding peptic ulcers and Helicobacter pylori infections. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:658108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Malfertheiner P. The intriguing relationship of Helicobacter pylori infection and acid secretion in peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer. Dig Dis. 2011;29:459-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Abu Daya H, Eloubeidi M, Tamim H, Halawi H, Malli AH, Rockey DC, Barada K. Opposing effects of aspirin and anticoagulants on morbidity and mortality in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Dig Dis. 2014;15:283-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kim JM, Jeong SH, Lee YJ, Park ST, Choi SK, Hong SC, Jung EJ, Ju YT, Jeong CY, Ha WS. Analysis of risk factors for postoperative morbidity in perforated peptic ulcer. J Gastric Cancer. 2012;12:26-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ohmann C, Imhof M, Ruppert C, Janzik U, Vogt C, Frieling T, Becker K, Neumann F, Faust S, Heiler K. Time-trends in the epidemiology of peptic ulcer bleeding. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:914-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Zeitoun JD, Rosa-Hézode I, Chryssostalis A, Nalet B, Bour B, Arpurt JP, Denis J, Nahon S, Pariente A, Hagège H. Epidemiology and adherence to guidelines on the management of bleeding peptic ulcer: a prospective multicenter observational study in 1140 patients. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:227-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Mahmood SS, Levy D, Vasan RS, Wang TJ. The Framingham Heart Study and the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease: a historical perspective. Lancet. 2014;383:999-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 856] [Cited by in RCA: 902] [Article Influence: 82.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Soedamah-Muthu SS, Stehouwer CD. Cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus: management strategies. Treat Endocrinol. 2005;4:75-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Velagapudi P, Turagam MK, Agrawal H, Mittal M, Kocheril AG, Aggarwal K. Antithrombotics in atrial fibrillation and coronary disease. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2014;12:977-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Singer DE, Go AS. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Clin Geriatr Med. 2001;17:131-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Burger W, Chemnitius JM, Kneissl GD, Rücker G. Low-dose aspirin for secondary cardiovascular prevention - cardiovascular risks after its perioperative withdrawal versus bleeding risks with its continuation - review and meta-analysis. J Intern Med. 2005;257:399-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 621] [Cited by in RCA: 548] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Emberson J, Godwin J, Peto R, Buring J, Hennekens C, Kearney P, Meade T. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1849-1860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2851] [Cited by in RCA: 2609] [Article Influence: 163.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Lanas Á. [Gastrointestinal bleeding, NSAIDs, aspirin and anticoagulants]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;37 Suppl 3:62-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Leiva-Pons JL, Carrillo-Calvillo J, Leiva-Garza JL, Loyo-Olivo MA, Piãa-Ramírez BM, López-Quijano JM, Celaya-Lara S, Cerda-Alanís R, Guerrero H. Importance of the time for stopping the combined use of aspirin and clopidogrel in patients undergoing coronary artery by-pass graft surgery. Arch Cardiol Mex. 2008;78:178-186. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Ghaffarinejad MH, Fazelifar AF, Shirvani SM, Asdaghpoor E, Fazeli F, Bonakdar HR, Noohi F. The effect of preoperative aspirin use on postoperative bleeding and perioperative myocardial infarction in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Cardiol J. 2007;14:453-457. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Manzano-Fernández S, Pastor FJ, Marín F, Cambronero F, Caro C, Pascual-Figal DA, Garrido IP, Pinar E, Valdés M, Lip GY. Increased major bleeding complications related to triple antithrombotic therapy usage in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary artery stenting. Chest. 2008;134:559-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kim SY, Hyun JJ, Suh SJ, Jung SW, Jung YK, Koo JS, Yim HJ, Park JJ, Chun HJ, Lee SW. Risk of Vascular Thrombotic Events Following Discontinuation of Antithrombotics After Peptic Ulcer Bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:e40-e44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Vist GE, Hagen KB, Devereaux PJ, Bryant D, Kristoffersen DT, Oxman AD. Systematic review to determine whether participation in a trial influences outcome. BMJ. 2005;330:1175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |