Published online Oct 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i39.7129

Peer-review started: December 9, 2016

First decision: January 10, 2017

Revised: March 22, 2017

Accepted: May 4, 2017

Article in press: May 4, 2017

Published online: October 21, 2017

Processing time: 316 Days and 8.7 Hours

To evaluate the short-term outcomes and quality of life (QoL) in gastric cancer patients undergoing digestive tract construction using the isoperistaltic jejunum-later-cut overlap method (IJOM) after totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy (TLTG).

A total of 507 patients who underwent laparoscopic gastrectomy (D2) from January 2014 to March 2016 were originally included in the study. The patients were divided into two groups to undergo digestive tract construction using either IJOM after TLTG (group T, n = 51) or Roux-en-Y anastomosis after laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy (LATG) (group A, n = 456). The short-term outcomes and QoL were compared between the two groups after 1:2 propensity-score matching (PSM). We used a questionnaire to assess QoL.

Before matching, age, sex, tumor size, tumor location, preoperative albumin and blood loss were significantly different between the two groups (P < 0.05). After PSM, the patients were well balanced in terms of their clinicopathological characteristics, although both blood loss and in-hospital postoperative days in group T were significantly lower than those in group A (P < 0.05). After matching, group T reported better QoL in the domains of pain and dysphagia. Among the items evaluating pain and dysphagia, group T tended to report better QoL (“Have you felt pain” and “Have you had difficulty eating solid food”) (P < 0.05).

The IJOM for digestive tract reconstruction after TLTG is associated with reduced blood loss and less pain and dysphagia, thus improving QoL after laparoscopic gastrectomy.

Core tip: This paper used propensity score-matched analysis and questionnaire survey to evaluate the short-term outcomes and quality of life (QoL) in patients who underwent digestive tract reconstruction using the isoperistaltic jejunum-later-cut overlap method (IJOM) after totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy (TLTG) and in patients who underwent Roux-en-Y anastomosis after laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy. We found the IJOM for digestive reconstruction after TLTG is associated with reduced blood loss and less pain and dysphagia, thus improving the QoL after laparoscopic gastrectomy.

- Citation: Huang ZN, Huang CM, Zheng CH, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lin JX, Lu J, Chen QY, Cao LL, Lin M, Tu RH, Lin JL. Digestive tract reconstruction using isoperistaltic jejunum-later-cut overlap method after totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: Short-term outcomes and impact on quality of life. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(39): 7129-7138

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i39/7129.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i39.7129

Since Kitano et al[1] reported laparoscopic-assisted distal gastrectomy in 1991, laparoscopic techniques and instruments have improved substantially. Consequently, totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy is increasingly employed and has a proven history of safety and feasibility[2-8]. However, although scholars have reported a variety of totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy (TLTG) methods[3,9-13], this technique has not been widely adopted because of the technological difficulty inherent in digestive reconstruction. Interest in improving the postoperative appearance and quality of life (QoL) in patients with gastric cancer has been increased. This goal, combined with the reduced trauma associated with TLTG, has heightened interest in developing ways to improve TLTG. Surgeons have primarily adopted the overlap or functional end-to-end method for digestive tract reconstruction after TLTG. However, these methods have drawbacks, such as jejunal freeness, which is seen particularly frequently with large anastomoses. Therefore, we devised the isoperistaltic jejunum-later-cut overlap method (IJOM), which involves esophagojejunostomy anastomosis after TLTG. Using this technique, we believe that the jejunum can be positioned with greater ease, thereby reducing the difficulties encountered with the anastomosis. However, little is known about the short-term outcomes and QoL of patients following the implementation of this IJOM for digestive reconstruction after TLTG. Thus, this study aimed to assess the short-term outcomes and QoL in gastric cancer patients undergoing digestive tract reconstruction with IJOM after TLTG and with Roux-en-Y anastomosis after LATG using propensity-score matching (PSM)[14,15] and a QoL assessment scale.

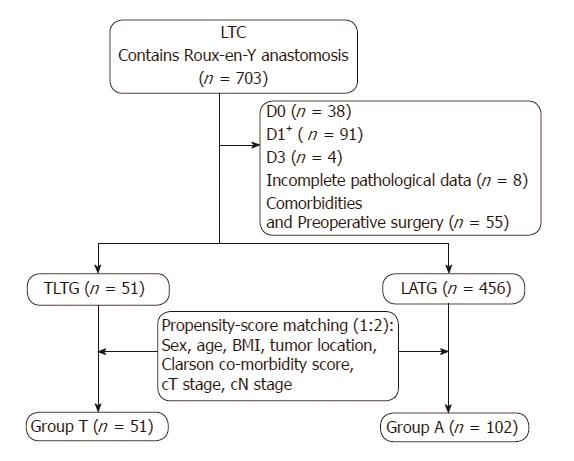

Between January 2014 to March 2016, data were collected from 703 patients who underwent laparoscopic gastrectomy at Fujian Medical University Union Hospital. The including criteria were: (1) pathologically proved gastric cancer by endoscopic biopsy specimen analysis; (2) the aforementioned examination indicated no evidence of distant metastasis; and (3) postoperative pathological diagnosis was curative R0. The exclusion criteria were: (1) intraoperatively proved distant metastasis; (2) T4b stage; (3) missing pathological data; (4) neoadjuvant therapy; and (5) comorbidities that could influence QoL (e.g., previous or combined malignancies; cardiovascular disease; cerebrovascular disease; neurological conditions, such as dementia and seizure; and severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring persistent medical aid). A number of 507 patients were eligible. Group T consisted of 51 patients who underwent the IJOM after TLTG, and group A comprised 456 patients who received a Roux-en-Y anastomosis after LATG. The 1:2 PSM was performed. Ultimately, group T included 51 patients and group A included 102 patients (Figure 1).

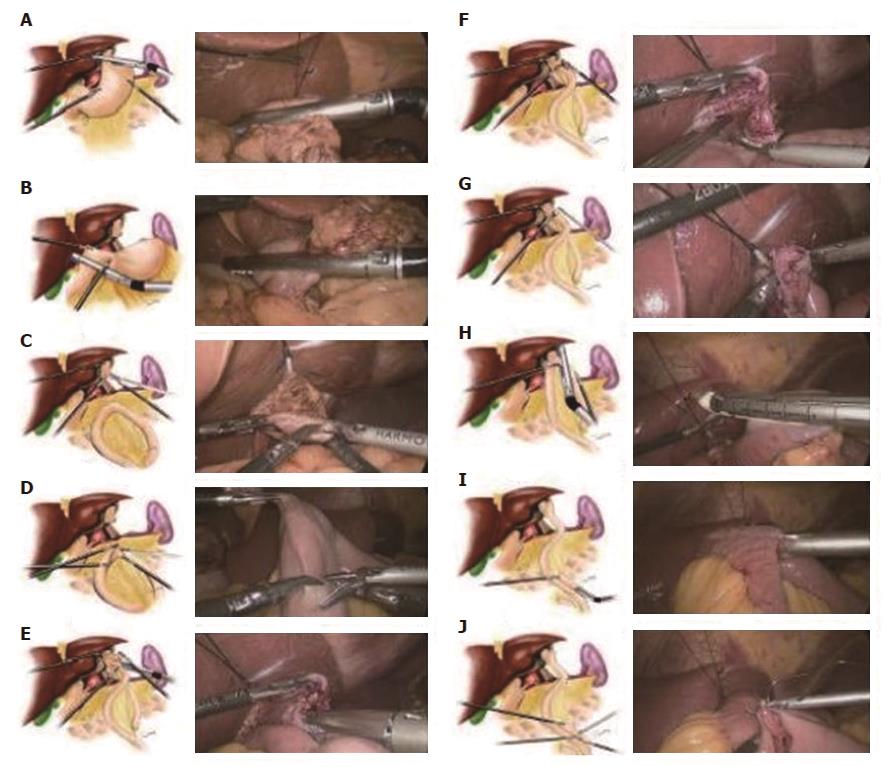

In group T, the IJOM was performed after TLTG. After dissecting the lymph nodes laparoscopically and mobilizing the esophagus (Figure 2A) and the duodenum (Figure 2B), an endoscopic linear stapler was used to transect them sequentially in predetermined locations. Two small incisions were made on the left side of the resection margin of the esophagus (Figure 2C) and the antimesenteric border of the jejunum (Figures 2D) approximately 20 cm away from the ligament of Treitz, respectively.

Then, the two limbs of the stapler were inserted into each incision, respectively, and the forks of the stapler were closed and fired, achieving a side-to-side esophagojejunostomy (Figure 2E). After confirming that there was no bleeding via common stab incision (Figure 2F), the common stab was manually sutured (Figure 2G). Then, the jejunum was transected after baring the mesenteric border approximately 1 cm into the jejunum wall and approximately 3 cm away from the esophagojejunostomy (Figure 2H). After a small incision was made each on the antimesenteric border of the margin of the proximal jejunum and the distal jejunum roughly about 45 cm from esophagojejunostomy, the two limbs of the stapler were inserted into each incision, and the forks of the stapler were closed and fired to achieve a side-to-side jejunojejunostomy (Figure 2I). After confirming that there was no bleeding or damage to jejunal mucosa by common stab incision, the common stab incision was sutured laparoscopically (Figure 2J). Finally, we removed the specimen through a 3.5-cm incision on the lower abdomen. The differences between this method and other esophagojejunostomy anastomosis techniques are summarized in Table 1.

| Anastomosis surgeon | Characteristics | Merit | Demerit |

| Uyama et al[12] | The anastomosis line is vertical with esophageal long axis | Anastomotic is large enough | The number of anastomosis linear staplers is much |

| Jejunum is located in the right side of the esophagus. | |||

| Matsui et al[37] | Complete the anastomosis before severed esophagus | The number of anastomosis linear staplers is reduced | Probably develop dysphagia 6 mo after operation |

| Close the stoma and resect specimens at the same time | |||

| Jejunum is located in the right side of the esophagus | |||

| Lee et al[13] | Suture esophagus, jejunum and right angle of diaphragm after anastomosis | Reduce the incidence of esophageal hiatal hernia and anastomotic fistula | Increase the operation time |

| Jejunum is located in the right side of the esophagus | |||

| Okabe et al[38] | Before anastomosis, the specimens was removed | The size of anastomotic stoma is bigger | The technique is difficult |

| Jejunum is located in the left side of the esophagus | |||

| Inaba et al[29] | Overlap anastomosis | Isoperistaltic anastomosis meets the physiological needs | The jejunum is free and difficult for anastomosis |

| Divide the jejunum before anastomosis | |||

| Matsui et al[39] | Overlap anastomosis | Isoperistaltic anastomosis meets the physiological needs | The jejunum is free and difficult for anastomosis |

| Divide the esophagus after anastomosis |

For patients in group T, the lymph nodes were dissected laparoscopically, and the esophagus and duodenum were mobilized. Then, the traditional open Roux-en-Y anastomosis was performed using a circular stapler[16].

All patients signed the informed consent form before operation. Preoperative computed tomography (CT) scanning, ultrasonography of the abdomen and endoscopic ultrasonography were routinely performed. When distant metastasis was suspected, positron emission tomography was performed. Preoperative morbidities were scored according to the Charlson score system[17]. Tumor staging was performed according to the 7th edition of the International Union against Cancer (UICC) classification[18]. Postoperative anastomosis-related complications were diagnosed by gastrografin esophagram or clinical manifestations and stratified using the Clavien-Dindo classification[19]. Perioperative death was defined as death that occurred during hospitalization. The Institutional Review Board of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital approved this study.

We used the validated Chinese version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer 30-item core QoL questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ-C30)[20] to assess QoL. The questionnaire includes a global health status, five functional items, three symptom dimensions, and six individual symptom items (Table 2). Furthermore, we used the validated Chinese version of the 22-item EORTC-QLQ gastric cancer module (EORTC-QLQ-STO22)[21] to assess tumor-specific QoL. This questionnaire includes a functional scale, five symptom dimensions, and three individual symptom scales. QoL is represented by a score ranging from 0 to 100 for every scale. Better QoL is indicated by the higher scores in the functional scales of the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and lower scores in the symptom scores of EORTC-QLQ-C30 and STO22 (Table 2).

| Scale | Number of constituting items |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| Global health status/QoL scale1 | 2 |

| Functional scales1 | |

| Physical functioning | 5 |

| Role functioning | 2 |

| Emotional functioning | 4 |

| Cognitive functioning | 2 |

| Social functioning | 2 |

| Symptom scales2 | |

| Fatigue | 3 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 2 |

| Pain | 2 |

| Dyspnoea | 1 |

| Insomnia | 1 |

| Appetite loss | 1 |

| Constipation | 1 |

| Diarrhoea | 1 |

| Financial difficulties | 1 |

| EORTC-QLQ-STO222 | |

| Dysphagia | 3 |

| Chest and abdominal pain | 4 |

| Reflux | 3 |

| Eating restrictions | 4 |

| Anxieties | 3 |

| Dry mouth | 1 |

| Taste problem | 1 |

| Body image | 1 |

| Hair loss | 2 |

The follow-ups were performed via mailing, telephone call, or outpatient service. We explained the content of each item of the questionnaire to the patients 6 mo postoperatively, and the patients chose their own responses. Most patients underwent physical examinations, laboratory tests, chest radiography, abdominal ultrasonography or CT, and annual endoscopic examinations.

The Statistical Package for Social Science version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States) was used to perform statistical analyses. The t tests or paired t tests were performed to compare continuous variables. χ2 tests were performed to compare categorical variables. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Before matching, age, sex, tumor location, tumor size, and preoperative albumin level differed significantly between the two groups (P < 0.05). After 1:2 matching, 51 and 102 patients were included in groups T and A, respectively, and well balanced in their clinicopathological characteristics (Table 3).

| All patients | Propensity-matched patients | |||||

| Group T (n = 51) | Group A (n = 456) | P value | Group T (n = 51) | Group A (n = 102) | P value | |

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 55.5 ± 12.1 | 61.6 ± 11.2 | < 0.001 | 55.5 ± 12.1 | 55.9 ± 11.0 | 0.916 |

| Gender | < 0.001 | 1.000 | ||||

| Male | 34 | 345 | 34 | 68 | ||

| Female | 17 | 111 | 17 | 34 | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | 0.281 | 0.608 | ||||

| 0 | 48 | 418 | 48 | 92 | ||

| 1-2 | 3 | 38 | 3 | 10 | ||

| BMI (mean ± SD, kg/m2) | 22.5 ± 13.1 | 22.3 ± 13.5 | 0.919 | 22.5 ± 13.1 | 22.6 ± 12.8 | 0.965 |

| Tumor size (mean ± SD, cm) | 4.5 ± 1.5 | 4.9 ± 1.3 | 0.041 | 4.5 ± 1.5 | 4.7 ± 1.7 | 0.142 |

| Tumor location | < 0.001 | 0.177 | ||||

| Upper third | 4 | 188 | 4 | 12 | ||

| Middle third | 34 | 169 | 34 | 76 | ||

| Whole | 13 | 99 | 13 | 14 | ||

| Histology type | 0.453 | 0.482 | ||||

| Differentiation | 47 | 416 | 47 | 97 | ||

| Undifferentiation | 4 | 40 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Preoperative albumin (mean ± SD, g/L) | 40.8 ± 4.3 | 39.1 ± 5.2 | 0.025 | 40.8 ± 4.3 | 40.6 ± 4.6 | 0.796 |

| Depth of infiltration (T) | 0.174 | 0.643 | ||||

| T1 | 15 | 82 | 15 | 23 | ||

| T2 | 8 | 83 | 8 | 18 | ||

| T3 | 10 | 135 | 10 | 16 | ||

| T4a | 18 | 166 | 18 | 45 | ||

| Nodal status (N) | 0.729 | 0.534 | ||||

| N0 | 21 | 190 | 21 | 34 | ||

| N1 | 11 | 77 | 11 | 18 | ||

| N2 | 5 | 66 | 5 | 10 | ||

| N3 | 14 | 123 | 14 | 40 | ||

| UICC stage | 0.319 | 0.502 | ||||

| I | 13 | 78 | 13 | 18 | ||

| II | 17 | 159 | 17 | 40 | ||

| III | 21 | 219 | 21 | 44 | ||

After matching, blood loss and postoperative days of hospital stay were significantly less in group T than in group A (P < 0.05). The number of harvested lymph nodes, operative time, time to first flatus, time to fluid diet, and hospitalization costs were similar in the two groups (Table 4).

| All patients | Propensity-matched patients | |||||

| Group T (n = 51) | Group A (n = 456) | P value | Group T (n = 51) | Group A (n = 102) | P value | |

| Operative time, min (mean ± SD) | 209.3 ± 41.0 | 203.6 ± 49.3 | 0.427 | 209.3 ± 41.0 | 200.5 ± 55.6 | 0.318 |

| Blood loss, mL (mean ± SD) | 48.3 ± 38.5 | 98.4 ± 149.1 | 0.017 | 48.3 ± 38.5 | 105.4 ± 147.9 | 0.008 |

| Harvested LNs (mean ± SD) | 44.5 ± 15.0 | 41.2 ± 14.2 | 0.237 | 44.5 ± 15.0 | 42.6 ± 15.2 | 0.465 |

| Time to first flatus, days (mean ± SD) | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 3.5 ± 1.7 | 0.220 | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 3.6 ± 1.2 | 0.332 |

| Time to fluid diet, days (mean ± SD) | 5.6 ± 1.4 | 5.6 ± 1.6 | 1 | 5.6 ± 1.4 | 5.5 ± 1.9 | 0.739 |

| Postoperative days (mean ± SD) | 12.6 ± 4.3 | 14.7 ± 8.9 | 0.097 | 12.6 ± 4.3 | 15.4 ± 8.9 | 0.035 |

| hospitalization costs, yuan | 75450 ± 20038 | 73308 ± 21932 | 0.505 | 75450 ± 20038 | 70407 ± 13254 | 0.065 |

| Chemotherapy | 33 | 310 | 0.635 | 33 | 78 | 0.123 |

Before matching, one patient had an anastomotic fistula in group T. In contrast, Group A included 22 patients with anastomotic fistula, one with anastomotic hemorrhage and four with anastomotic obstruction. The incidences of anastomosis-related complications were 2.0% and 5.9% in groups T and A, respectively; the two rates were similar. After matching, there was one patient with anastomotic fistula in group T, whereas there were four patients with anastomotic fistula, one with anastomotic hemorrhage, and two with an anastomotic obstruction in group A. The incidence of anastomosis-related complications had no statistical difference in the two groups, and no perioperative deaths occurred (Table 5).

| All patients | Propensity-matched patients | |||||

| Group T, % (n = 456) | Group A, % (n = 51) | P value | Group T, % (n = 102) | Group A, % (n = 51) | P value | |

| Morbidity | 1 (2.0) | 27 (5.9) | 0.893 | 1 (1.9) | 6 (11.8) | 0.552 |

| Anastomotic fistula | 1 | 22 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Anastomotic hemorrhage | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Anastomotic obstruction | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Mortality | 0 | 0 | / | 0 | 0 | / |

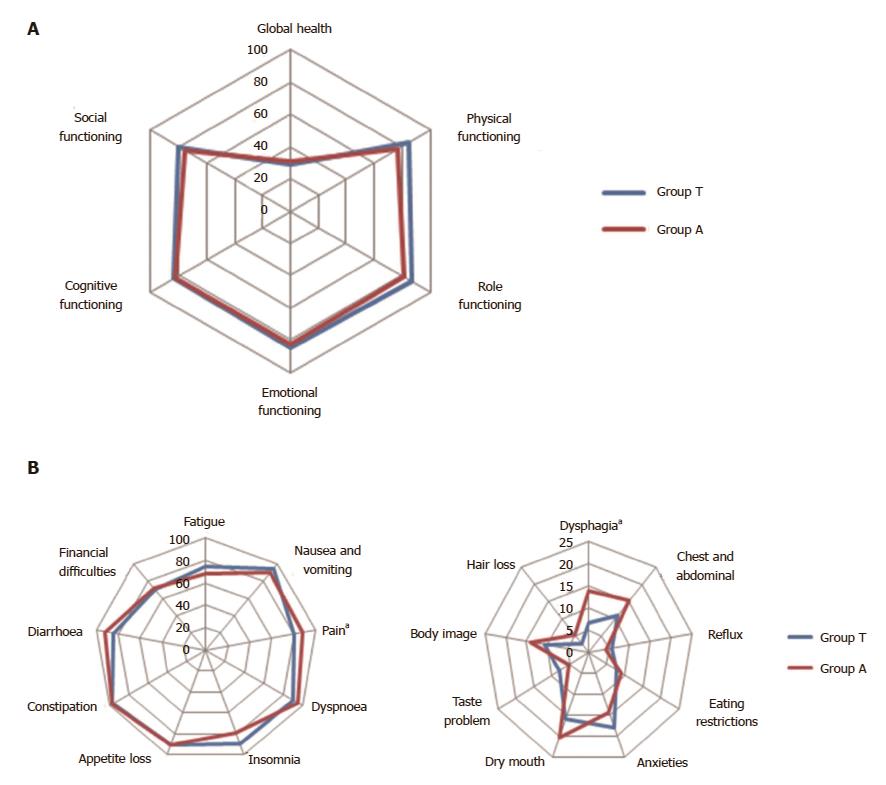

After matching, six patients died and one was lost to follow-up 6 mo postoperatively in group T. Eventually, 44 patients joined the questionnaire survey. In group A, ten patients died, and three were lost to follow-up. A total of 89 patients from group A participated in the questionnaire survey. The functional scales of EORTC-QLQ-C30 were all similar in both groups (Figure 2).

After matching, the symptom scales of EORTC-QLQ-C30 and STO22 were compared. Based on the pain scales of EORTC-QLQ-C30 and dysphagia scales of EORTC QLQ-STO22, group T reported better QoL (Figure 3). Subgroup analyses of two items in the pain scale (“Have you felt pain?” and “Has your life been affected by pain?”), group T tended to report better QoL in “Have you felt pain?”(P = 0.018). In the dysphagia scale, subgroup analyses of three items (“Have you had difficulty eating solid food?”, “Have you had difficulty swallowing liquid or eating soft food?”, and “Have you had difficulty drinking water?”) revealed that group T tended to report better QoL in response to the question “Have you had difficulty eating solid food?” than group A (P = 0.039) (Table 6).

| Propensity-matched patients | |||

| Group T (n = 44) | Group A (n = 89) | P value | |

| Constituent items of pain of EORTC-QLQ-C30 | |||

| Have you felt pain? | 0.018 | ||

| Not at all | 28 | 66 | |

| A little | 12 | 7 | |

| Quite a lot | 3 | 14 | |

| Very much | 1 | 2 | |

| Have your life affected by pain? | 0.271 | ||

| Not at all | 39 | 73 | |

| A little | 4 | 7 | |

| Quite a lot | 1 | 9 | |

| Very much | 0 | 0 | |

| Constituent items of dysphagia of EORTC-QLQ-STO22 | |||

| Have you felt difficult to eat solid food? | 0.039 | ||

| Not at all | 26 | 31 | |

| A little | 11 | 32 | |

| Quite a lot | 7 | 21 | |

| Very much | 0 | 5 | |

| Have you felt difficult to eat liquid of soft food? | 0.275 | ||

| Not at all | 38 | 67 | |

| A little | 5 | 15 | |

| Quite a lot | 1 | 7 | |

| Very much | 0 | 0 | |

| Have you felt difficult to drink water? | 0.194 | ||

| Not at all | 39 | 80 | |

| A little | 5 | 5 | |

| Quite a lot | 0 | 4 | |

| Very much | 0 | 0 | |

Laparoscopy offers several advantages over traditional laparotomy, such as reduced trauma, faster recovery, fewer postoperative complications, and greater aesthetic appeal. These benefits are attributable to the minimal invasiveness of laparoscopy and the good clinical outcomes that have been reported[22-25]. Currently, the methods of digestive tract reconstruction employed after LG include LATG and TLTG. In LATG, the digestive tract reconstruction is performed via a small incision after lymphadenectomy, although this decreases the advantages of laparoscopic minimally invasive surgery. Since Uyama et al[12] reported totally laparoscopic digestive tract reconstruction, substantial research in Japan and Korea has revealed that TLTG has desirable short-term outcomes and is also safe and effective[11,26-28].

Currently, the digestive tract reconstruction methods used after TLTG include overlap[12] and functional end-to-end[29] techniques. However, jejunal freeness is one of several drawbacks associated with these methods and makes the anastomosis more difficult. Therefore, we devised the IJOM, which involves esophagojejunostomy anastomosis after TLTG. We believe that, using this technique, the jejunum can be more easily positioned, thereby reducing the difficulty in creating the anastomosis. Moreover, because the proximal jejunum is divided after the anastomosis, the length of the blind loops can be easily grasped. We found that blood loss was reduced in group T, and this may be attributed to the clearer, amplified field of vision achieved during laparoscopic digestive tract reconstruction. As a result, blood vessels in the muscles and mesentery can be more readily identified and are less likely to be transected during the procedure. Consistent with our findings, previous studies have shown that reduced blood loss is associated with better postoperative recovery[30]. We found that the length of the postoperative stay in group T was significantly shorter than that in group A, confirming that less trauma and blood loss during TLTG can promote faster recovery.

Lee et al[31] showed that distal gastrectomy decreases the QoL because of problems with eating restrictions and body image. However, compared with open surgery, laparoscopic-assisted distal gastrectomy improves QoL, specifically by reducing the incidence of postoperative intestinal obstruction[32]. Fujii et al[33] suggested that this reduction in postoperative intestinal obstruction may be attributable to the less abdominal manipulation required for laparoscopic surgery, which may blunt the systemic cytokine and inflammatory responses[34,35]. Similarly, totally laparoscopic technology reduces the amount of intestinal manipulation required during digestive tract reconstruction and may also reduce the incidence of postoperative intestinal obstruction. However, no studies have evaluated QoL following totally laparoscopic surgery. Schneider et al[36] reported that the diameter of the anastomotic stoma obtained using the linear stapler was significantly larger than that achieved with the circular stapler, which benefits the passage of food. At 6 mo post-surgery, we found that symptoms of dysphagia were better in group T, especially in terms of eating solid food. This finding indicates that using a linear stapler can expand the diameter of the anastomotic stoma and that the decreased intestinal manipulation involved in TLTG can reduce the incidence of intestinal obstruction.

Patients who underwent TLTG reported significantly less pain than those undergoing LATG. We believe that this is because the incision in the abdominal wall involved in TLTG is shorter, leading to less pain from inflammation and scar formation. In addition, less intra-abdominal manipulation likely contributes to decreasing the formation of intra-abdominal adhesions and, thus, the associated discomfort.

This is the first study investigating the differences in short-term outcomes and QoL between the IJOM after TLTG and Roux-en-Y anastomosis after LATG using PSM and a QoL assessment scale. The results show that utilizing the IJOM after TLTG can reduce intra-operative blood loss and relieve symptoms of pain and dysphagia. However, this study has several limitations. First, the follow-up period was short. Second, a retrospective, single-center design was used. Therefore, a prospective, multiple-center study with a longer follow-up period is needed.

Surgeons have primarily adopted several methods for digestive tract reconstruction after totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy (TLTG). However, these methods have drawbacks, such as jejunal freeness and difficult to perform. Therefore, we devised the isoperistaltic jejunum-later-cut overlap method (IJOM), but little is known about the short-term outcome and quality-of-life (QoL) in patients following the implementation of this digestive reconstruction.

The QoL after distal gastrectomy was reported to be affected by eating restrictions and body image. For TLTG, scholars have reported a variety of digestive reconstruction methods which are safe and effective, but the QoL is uncertain.

The authors used propensity score-matched analysis and questionnaire survey to perform this research. The authors found that IJOM for digestive reconstruction can reduce blood loss compared with Roux-en-Y anastomosis and was associated with less pain and dysphagia, thus improving QoL after laparoscopic gastrectomy.

Through this study, we can focus the symptoms which probably happen after surgery and accordingly improve the QoL of patients. However, a prospective, multiple-center study with a longer follow-up period is needed.

EORTC-QLQ-C30: Chinese version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer 30-item core QoL questionnaire. EORTC-QLQ-STO22: the validated Chinese version of the 22-item EORTC-QLQ gastric cancer module. PSM: A statistical matching method which can reduce the bias of variables.

This study is a pioneer study about esophagojejunostomy anastomosis after TLTG.

The authors are thankful to Fujian Medical University Union Hospital for the management of our gastric cancer patient database.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chiu CC S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:146-148. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Kanaya S, Gomi T, Momoi H, Tamaki N, Isobe H, Katayama T, Wada Y, Ohtoshi M. Delta-shaped anastomosis in totally laparoscopic Billroth I gastrectomy: new technique of intraabdominal gastroduodenostomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195:284-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim JJ, Song KY, Chin HM, Kim W, Jeon HM, Park CH, Park SM. Totally laparoscopic gastrectomy with various types of intracorporeal anastomosis using laparoscopic linear staplers: preliminary experience. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:436-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Song KY, Park CH, Kang HC, Kim JJ, Park SM, Jun KH, Chin HM, Hur H. Is totally laparoscopic gastrectomy less invasive than laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy?: prospective, multicenter study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1015-1021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tanimura S, Higashino M, Fukunaga Y, Takemura M, Nishikawa T, Tanaka Y, Fujiwara Y, Osugi H. Intracorporeal Billroth 1 reconstruction by triangulating stapling technique after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18:54-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Oki E, Sakaguchi Y, Ohgaki K, Minami K, Yasuo S, Akimoto T, Toh Y, Kusumoto T, Okamura T, Maehara Y. Surgical complications and the risk factors of totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:146-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bracale U, Rovani M, Bracale M, Pignata G, Corcione F, Pecchia L. Totally laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: meta-analysis of short-term outcomes. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2012;21:150-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bouras G, Lee SW, Nomura E, Tokuhara T, Nitta T, Yoshinaka R, Tsunemi S, Tanigawa N. Surgical outcomes from laparoscopic distal gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y reconstruction: evolution in a totally intracorporeal technique. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:37-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim HS, Kim MG, Kim BS, Yook JH, Kim BS. Totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy using endoscopic linear stapler: early experiences at one institute. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22:889-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Siani LM, Ferranti F, Corona F, Quintiliani A. [Totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy with esophago-jejunal termino-lateral anastomosis by Or-Vil device for carcinoma. Our experience in ten consecutive patients]. G Chir. 2010;31:215-219. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kim HS, Kim BS, Lee IS, Lee S, Yook JH, Kim BS. Comparison of totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy and open total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013;23:323-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Uyama I, Sugioka A, Fujita J, Komori Y, Matsui H, Hasumi A. Laparoscopic total gastrectomy with distal pancreatosplenectomy and D2 lymphadenectomy for advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 1999;2:230-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lee IS, Kim TH, Kim KC, Yook JH, Kim BS. Modified techniques and early outcomes of totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy with side-to-side esophagojejunostomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22:876-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim YG, Graham DY, Jang BI. Proton pump inhibitor use and recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated disease: a case-control analysis matched by propensity score. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:397-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lonjon G, Boutron I, Trinquart L, Ahmad N, Aim F, Nizard R, Ravaud P. Comparison of treatment effect estimates from prospective nonrandomized studies with propensity score analysis and randomized controlled trials of surgical procedures. Ann Surg. 2014;259:18-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Fukuhara K, Osugi H, Takada N, Takemura M, Higashino M, Kinoshita H. Reconstructive procedure after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer that best prevents duodenogastroesophageal reflux. World J Surg. 2002;26:1452-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5537] [Cited by in RCA: 6462] [Article Influence: 430.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhu GL, Sun Z, Wang ZN, Xu YY, Huang BJ, Xu Y, Zhu Z, Xu HM. Splenic hilar lymph node metastasis independently predicts poor survival for patients with gastric cancers in the upper and/or the middle third of the stomach. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:786-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365-376. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Bottomley A, Vickery C, Arraras J, Sezer O, Moore J, Koller M, Turhal NS, Stuart R. Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-STO 22, to assess quality of life in patients with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2260-2268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Huscher CG, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Sansonetti A, Di Paola M, Recher A, Ponzano C. Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer: five-year results of a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2005;241:232-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 650] [Cited by in RCA: 655] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Uyama I, Sugihara K, Tanigawa N; Japanese Laparoscopic Surgery Study Group. A multicenter study on oncologic outcome of laparoscopic gastrectomy for early cancer in Japan. Ann Surg. 2007;245:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 519] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Park DJ, Han SU, Hyung WJ, Kim MC, Kim W, Ryu SY, Ryu SW, Song KY, Lee HJ, Cho GS, Kim HH; Korean Laparoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Study (KLASS) Group. Long-term outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a large-scale multicenter retrospective study. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1548-1553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Qiu J, Pankaj P, Jiang H, Zeng Y, Wu H. Laparoscopy versus open distal gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Topal B, Leys E, Ectors N, Aerts R, Penninckx F. Determinants of complications and adequacy of surgical resection in laparoscopic versus open total gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:980-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Moisan F, Norero E, Slako M, Varas J, Palominos G, Crovari F, Ibañez L, Pérez G, Pimentel F, Guzmán S. Completely laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for early and advanced gastric cancer: a matched cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:661-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kim HS, Kim MG, Kim BS, Lee IS, Lee S, Yook JH, Kim BS. Comparison of totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy and laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy methods for the surgical treatment of early gastric cancer near the gastroesophageal junction. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013;23:204-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Inaba K, Satoh S, Ishida Y, Taniguchi K, Isogaki J, Kanaya S, Uyama I. Overlap method: novel intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy after laparoscopic total gastrectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:e25-e29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Liang YX, Guo HH, Deng JY, Wang BG, Ding XW, Wang XN, Zhang L, Liang H. Impact of intraoperative blood loss on survival after curative resection for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5542-5550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lee SS, Chung HY, Kwon O, Yu W. Long-term Shifting Patterns in Quality of Life After Distal Subtotal Gastrectomy: Preoperative- and Healthy-based Interpretations. Ann Surg. 2015;261:1131-1137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yasuda K, Shiraishi N, Etoh T, Shiromizu A, Inomata M, Kitano S. Long-term quality of life after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2150-2153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Fujii K, Sonoda K, Izumi K, Shiraishi N, Adachi Y, Kitano S. T lymphocyte subsets and Th1/Th2 balance after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1440-1444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Braga M, Vignali A, Zuliani W, Radaelli G, Gianotti L, Martani C, Toussoun G, Di Carlo V. Metabolic and functional results after laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a randomized, controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1070-1077. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Leung KL, Lai PB, Ho RL, Meng WC, Yiu RY, Lee JF, Lau WY. Systemic cytokine response after laparoscopic-assisted resection of rectosigmoid carcinoma: A prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2000;231:506-511. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Schneider R, Gass JM, Kern B, Peters T, Slawik M, Gebhart M, Peterli R. Linear compared to circular stapler anastomosis in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass leads to comparable weight loss with fewer complications: a matched pair study. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2016;401:307-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Matsui H, Uyama I, Sugioka A, Fujita J, Komori Y, Ochiai M, Hasumi A. Linear stapling forms improved anastomoses during esophagojejunostomy after a total gastrectomy. Am J Surg. 2002;184:58-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Okabe H, Obama K, Tanaka E, Nomura A, Kawamura J, Nagayama S, Itami A, Watanabe G, Kanaya S, Sakai Y. Intracorporeal esophagojejunal anastomosis after laparoscopic total gastrectomy for patients with gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2167-2171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Matsui H, Okamoto Y, Nabeshima K, Nakamura K, Kondoh Y, Makuuchi H, Ogoshi K. Endoscopy-assisted anastomosis: a modified technique for laparoscopic side-to-side esophagojejunostomy following a total gastrectomy. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2011;4:107-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |