Published online Sep 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i34.6321

Peer-review started: June 8, 2017

First decision: July 13, 2017

Revised: July 27, 2017

Accepted: August 15, 2017

Article in press: August 15, 2017

Published online: September 14, 2017

Processing time: 99 Days and 23.1 Hours

To explore the natural history of covert hepatic encephalopathy (CHE) in absence of medication intervention.

Consecutive outpatient cirrhotic patients in a Chinese tertiary care hospital were enrolled and evaluated for CHE diagnosis. They were followed up for a mean of 11.2 ± 1.3 mo. Time to the first cirrhosis-related complications requiring hospitalization, including overt HE (OHE), resolution of CHE and death/transplantation, were compared between CHE and no-CHE patients. Predictors for complication(s) and death/transplantation were also analyzed.

A total of 366 patients (age: 47.2 ± 8.6 years, male: 73.0%) were enrolled. CHE was identified in 131 patients (35.8%). CHE patients had higher rates of death and incidence of complications requiring hospitalization, including OHE, compared to unimpaired patients. Moreover, 17.6% of CHE patients developed OHE, 42.0% suffered persistent CHE, and 19.8% of CHE spontaneously resolved. In CHE patients, serum albumin < 30 g/L (HR = 5.22, P = 0.03) was the sole predictor for developing OHE, and blood creatinine > 133 μmol/L (HR = 4.75, P = 0.036) predicted mortality. Child-Pugh B/C (HR = 0.084, P < 0.001) and OHE history (HR = 0.15, P = 0.014) were predictors of spontaneous resolution of CHE.

CHE exacerbates, persists or resolves without medication intervention in clinically stable cirrhosis. Triage of patients based on these predictors will allow for more cost-effect management of CHE.

Core tip: Covert hepatic encephalopathy (CHE) was prevalent in clinically-stable cirrhosis in the tertiary care hospital. A history of overt hepatic encephalopathy (OHE) was the only risk factor for CHE in patients with OHE history, while a high model for end-stage liver disease score was the only risk factor for those without OHE history. Natural history of CHE in the absence of medication intervention included development of complications, persistence or spontaneous resolution of CHE. Triage of patients based on predictors for exacerbation and resolution, rather than the degree of impairment in daily work productivity or quality of life, could make clinical management of CHE more cost-effective.

- Citation: Wang AJ, Peng AP, Li BM, Gan N, Pei L, Zheng XL, Hong JB, Xiao HY, Zhong JW, Zhu X. Natural history of covert hepatic encephalopathy: An observational study of 366 cirrhotic patients. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(34): 6321-6329

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i34/6321.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i34.6321

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a neuropsychiatric syndrome that is most commonly associated with decompensated liver cirrhosis and incorporates a spectrum of manifestations that range from mild cognitive impairment to coma. Generally, HE is subdivided into covert HE (CHE, including minimal HE and West-Haven grade I HE) and overt HE (OHE, West-Haven grades II-IV HE)[1,2]. CHE is regarded as the pre-clinical stage of OHE and occurs in 20%-80% of patients with cirrhosis. CHE is associated with increased progression to OHE[3-5], poor health-related quality of life (HRQOL)[6,7], and high risk for traffic violations and accidents[8]. It is also an independent predictor for death, liver-related complications and hospitalizations[9-11]. It is more detrimental for patients in manual labor professions (which involve complex occupational operation and driving of machinery) than those with desk jobs (which involve verbal and intellectual skills). Thus, CHE could endanger patients and their coworkers[12]. The decision to treat CHE depends on the degree of impairment in daily work productivity or quality of life of patients[1,2].

Several studies have investigated the natural history of CHE[3-5,9-11,13-18]. However, in these studies, treatment of other cirrhosis complications [such as antibiotics for infection or gastroesophageal variceal bleeding (GVB), lactulose for constipation, or albumin infusion for ascites or hepatorenal syndrome] was not restricted. The medication used to treat these complications during follow-up could hinder the occurrence of CHE and underestimate its disadvantages. Furthermore, perhaps not all CHE patients need to be treated. Thus, we hypothesized that CHE can persist or resolve spontaneously without medication intervention in some clinically-stable cirrhotic patients. Therefore, the aims of the present study were: (1) to observe the real natural history of CHE without medication intervention before development of cirrhosis related complications; and (2) to determine predictors for exacerbation and spontaneous resolution (SR) of CHE, in order to explore the therapeutic indications for CHE, based on natural course without medication intervention. Our findings will help CHE patient triage and lead to more precise and cost-effective clinical management.

This was an observational study performed between August, 2014 and November, 2016 at The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, which is a tertiary care level hospital in China. Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the hospital, and all participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Consecutive cirrhotic patients in the outpatient department of the hospital were screened and included in the study if they were > 18 and < 65 years of age and had a clinical, radiological or histological diagnosis of cirrhosis. Exclusion criteria included the following: presence or history of malignancy, including liver cancer; history of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt or shunt surgery; presence of systemic disease, significant head injury, neurological or psychiatric diseases; alcohol or psychoactive medication intake within 6 mo; antibiotics, lactulose, probiotics or L-ornithine-L-aspartate intake or albumin infusion within 6 wk; illiteracy or inability to perform neuropsychometric tests; or refusal to participate in the study. Patients with history of OHE within 6 mo of inclusion were also excluded to ensure total recovery of last OHE occurrence. As patients with resolved OHE may be at a risk for developing CHE, those patients with history of OHE 6 mo before inclusion were included.

OHE history was assessed based on a patient’s medical documents of hospitalization before inclusion. Patients were followed prospectively at intervals of 3 mo in the outpatient department of the hospital. Serial psychometric hepatic encephalopathy score (PHES) along with regular clinical and laboratory evaluations were measured at each visit until death, liver transplantation, or a follow-up of 12 mo after initial screening. If the patients did not show up for the 3-mo follow-up, they were tracked by telephone calls from the study staff. The time to death/liver transplantation and the occurrence of the first cirrhosis-related complications requiring hospitalization were recorded. Any medications recommended to treat CHE by established guidelines[1,2], including antibacterial agents, lactulose, probiotics, L-ornithine-L-aspartate and albumin infusion, had not been administered to patients unless necessary. However, these medications were not restricted if patients developed any complications and physicians thought these medications were necessary. In such cases, time to complications were documented. The Child-Pugh classification (CPC) and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scoring system were used to evaluate the severity of liver damage. All clinical data and assessment of complications were obtained from interviews or inpatient/outpatient medical documents.

Qualified physicians performed routine physical examinations and documented biochemical blood tests (i.e., complete blood count, alanine aminotransferase, total bilirubin, albumin, creatinine, prothrombin time, international normalization ratio), venous ammonia, virological blood tests [i.e., hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA and hepatitis C virus RNA levels], and diagnostic imaging (ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging). The etiology of cirrhosis, history of medication use, OHE and severity of ascites were documented.

The complications, which included OHE, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, hepatorenal syndrome, infections, primary hepatic carcinoma (PHC) and severe ascites requiring albumin infusion, were documented in mo. OHE was diagnosed clinically on the basis of impaired mental status, as defined by the West Haven Criteria, and impaired neuromotor function (i.e., hyperreflexia, rigidity, myoclonus and asterixis) that required initiation of HE-related therapy with or without hospitalization, and had corroboration from a caregiver[10,19]. GI bleeding was evidenced by melena, hematemesis or hematochezia. Infections were defined as bacterial infections, including pneumonia, sepsis with or without identified infectious focus, urinary tract infection, biliary tract infection, central nervous system infection (i.e., meningitis or brain abscess), and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. PHC diagnosis was based on imaging findings or liver biopsy.

PHES tests were used to define CHE. All patients underwent PHES tests in one morning session after breakfast in a quiet room without distracting noises. A specially trained medical doctor assisted the enrolled subjects in finishing these tests. Based on the nomograms of healthy volunteers, the PHES tests were described as abnormal if the score was < -4[10,20]. Persistence of CHE was defined if CHE patients survived and continued having abnormal PHES results until completion of follow up, in the absence of any of above-mentioned complication(s) or liver transplantation. As CHE runs a fluctuating course, CHE SR was defined if patients had normal PHES results for at least 6 mo at regular follow-up visits, in the absence of above-mentioned medications, complications or liver transplantation. Alternate forms of PHES tests (three parallel versions for each test in our study) were used at 3-mo interval visits to eliminate practice learning effects[21].

Based on a previous study, about 38% of CHE patients developed first OHE episode while about 17% of cirrhotic patients without CHE developed OHE[10]. Based on sample size calculations according to established formulas[22], the minimum sample size necessary for the current study was 78 patients in each group. It is reported that the prevalence of CHE in Chinese cirrhotic patients is about 40%. Thus, a minimum of 195 cirrhotic patients were enrolled to statistically compare the incidence of OHE between the CHE group and unimpaired group.

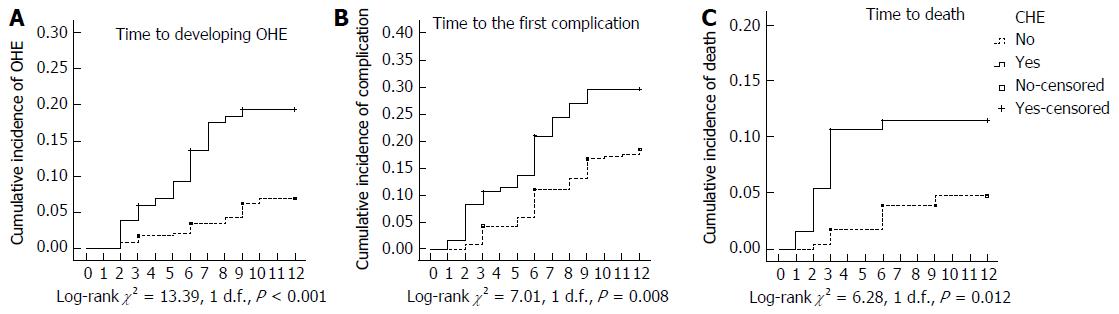

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD. Categorical variables were described as the number and proportion of each category. Rate differences of OHE development, development of the first cirrhosis-related complications requiring hospitalization and death, between patients with and without CHE, were estimated with Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank test. If patients did not develop OHE or other complications and survived, “truncated” was described in the Kaplan-Meier curve. In order to determine risk factors for CHE and predictors for the resolution of CHE, potential parameters were included and first analyzed in the univariate analysis. All tested variables with P values < 0.05 were entered into a logistic regression after adjusting for age, sex and level of education. The χ2 or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. The analysis of variance was performed as appropriate to determine associations for continuous data. All tested variables with P values < 0.05 were entered into a logistic regression after adjusting for age and sex. In order to determine predictors for developing OHE, the first cirrhosis-related complications requiring hospitalization or mortality in CHE patients, potential parameters were analyzed by univariate analysis. All tested variables with P values < 0.05 were entered into a Cox regression after adjusting for age and sex. All statistical analyses were two-tailed at the 5% level. We used the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, United States) to analyze our data.

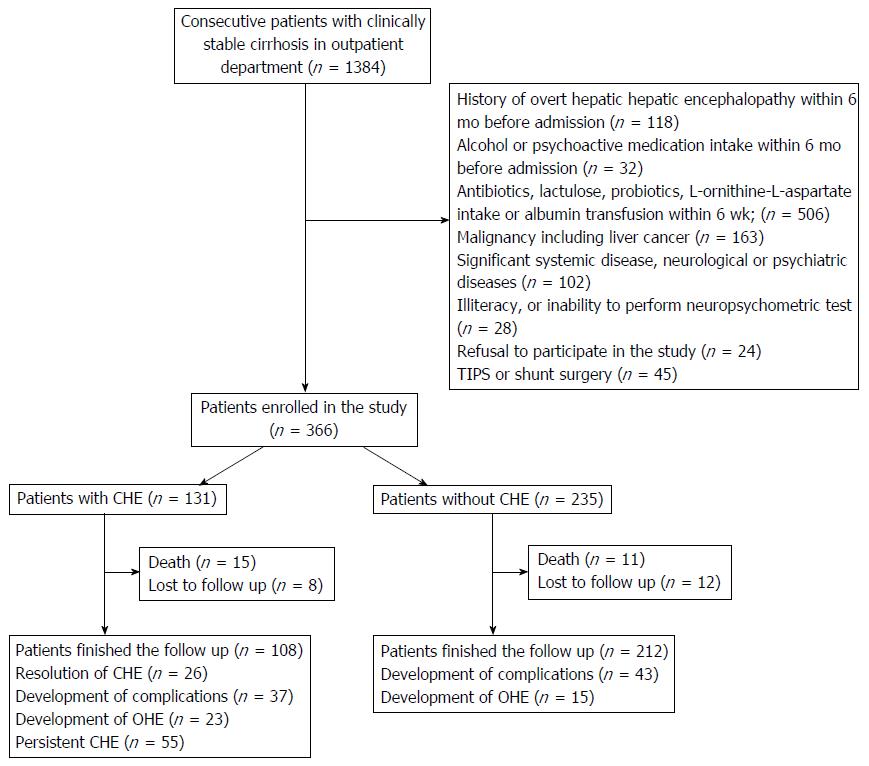

A total of 1384 consecutive outpatient cirrhotic patients were screened, and 366 patients (age: 47.2 ± 8.6 years, male: 73.0%, CPC-A: 43.2%, CPC-B: 50.5%, CPC-C: 6.3%, CPC score: 6.9 ± 1.6, MELD score: 15.4 ± 4.4) fulfilled the criteria and were enrolled in the study (Figure 1). Patients were followed for a mean of 11.2 ± 1.3 mo. CHE was identified in 131 (35.8%) patients. The clinical characteristics of CHE and the unimpaired group are shown in Table 1.

| Unimpaired, n =235 | CHE, n = 131 | P value | |

| Sex, female/male | 67/168 | 32/99 | 0.40 |

| Age in yr | 46.3 ± 8.9 | 48.8 ± 7.8 | 0.009 |

| Cause | |||

| HBV-associated | 180 (76.7) | 94 (71.8) | 0.31 |

| HCV-associated | 8 (3.4) | 4 (3.1) | 0.86 |

| Alcohol-associated | 25 (10.6) | 19 (14.5) | 0.28 |

| Others | 22 (9.4) | 14 (10.7) | 0.68 |

| Level of education | |||

| Primary school | 34 (14.5) | 45 (34.4) | < 0.001 |

| Junior high school | 99 (42.1) | 52 (39.7) | 0.65 |

| Senior high school | 70 (29.8) | 33 (25.2) | 0.35 |

| College degree or above | 32 (13.6) | 1 (0.8) | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine | 69.0 ± 16.3 | 71.3 ± 28.0 | 0.32 |

| Venous ammonia | 44.3 ± 4.2 | 57.9 ± 8.9 | < 0.001 |

| Albumin | 33.5 ± 7.7 | 26.2 ± 6.1 | < 0.001 |

| High total bilirubin | 17.3 ± 12.3 | 17.0 ± 9.1 | 0.76 |

| Platelets, 109/L | 102.6 ± 99.7 | 98.5 ± 96.7 | 0.70 |

| International normalization ratio | 1.14 ± 0.12 | 1.14 ± 0.15 | 0.99 |

| Ascites, none/mild/severe | 138/65/32 | 19/30/82 | < 0.001 |

| History of OHE | 12 (5.1) | 54 (41.2) | < 0.001 |

| CPC, N, A/B/C | 118/111/6 | 40/74/17 | < 0.001 |

| MELD score | 14.6 ± 2.9 | 16.9 ± 6.0 | 0.02 |

Compared with unimpaired patients, CHE patients were older and had a more frequent OHE history. After adjusting for age, sex and level of education, logistic analysis indicated that a history of OHE (β: 2.72, OR = 7.18, 95%CI: 3.45-14.92, P < 0.001) was the only risk factor for CHE in patients with OHE history, while a MELD score > 20 (β: 1.71, OR = 5.53, 95%CI: 1.33-22.89, P = 0.02) was the only risk factor for patients without OHE history.

Among the 366 patients included in this study, 323 (88.3%) completed the follow-up and survived. Twenty-three patients (unimpaired: 18.3% vs CHE: 28.2%) died, and 20 patients (unimpaired: 5.1% vs CHE: 6.1%) were lost to follow-up. None of the patients developed PHC or underwent liver transplantation during follow-up. The prevalence of cirrhosis-related complications requiring hospitalization and mortality were 28.2% and 11.5% in the CHE group vs 18.3% and 4.7% in the unimpaired group, respectively. Patients in the CHE group had higher rates of mortality (P = 0.012) and incidence of first cirrhosis-related complications requiring hospitalization (P = 0.008), including OHE (P < 0.001), compared to patients in the unimpaired group (Figure 2).

After 11.2 ± 1.3 mo of follow-up for 131 CHE patients, 108 patients (82.4%) had completed the follow-up and survived. Thirty-seven patients (28.2%) developed cirrhosis-related complications requiring hospitalization, including 23 patients that developed OHE (17.6%). Fifty-five patients (42.0%) suffered persistent CHE, while 26 patients (19.8%) had CHE SR. The comparisons of clinical characteristics between CHE patients with and without OHE development, between those with and without development of the cirrhosis-related complications requiring hospitalization, between those with and without CHE SR, and between survivors vs non-survivors during follow-up are shown in Table 2.

| Development of OHE | Complication(s) | Death | Resolution of CHE | |||||||||

| Yes, n = 23 | No, n = 108 | P value | Yes, n = 37 | No, n = 94 | P value | Yes, n = 15 | No, n = 116 | P value | Yes, n = 26 | No, n = 105 | P value | |

| Male sex | 19 (82.6) | 80 (74.1) | 0.39 | 33 (89.2) | 66 (70.2) | 0.02 | 14 (93.3) | 85 (73.3) | 0.09 | 14 (53.8) | 85 (81) | 0.004 |

| Age in yr | 46.4 ± 7.9 | 47.3 ± 8.7 | 0.56 | 47.3 ± 8.3 | 47.2 ± 8.7 | 0.90 | 44.7 ± 7.8 | 47.4 ± 8.6 | 0.13 | 47.8 ± 8.2 | 49.0 ± 7.8 | 0.48 |

| HBV-associated | 17 (73.9) | 77 (71.3) | 0.80 | 27 (73.0) | 67 (71.3) | 0.85 | 9 (60) | 85 (73.3) | 0.28 | 17 (65.4) | 77 (73.3) | 0.42 |

| Creatinine | 80.5 ± 42.7 | 68.6 ± 16.8 | 0.001 | 76.5 ± 33.2 | 68.0 ± 16.1 | 0.001 | 95.3 ± 46.4 | 67.9 ± 16.6 | < 0.001 | 72.6 ± 23.7 | 71.0 ± 29.1 | 0.80 |

| Albumin in g/L | 27.2 ± 8.1 | 31.3 ± 7.8 | 0.003 | 29.9 ± 7.9 | 31.1 ± 8.0 | 0.23 | 29.0 ± 8.4 | 31.0 ± 7.9 | 0.21 | 27.8 ± 5.3 | 25.8 ± 6.2 | 0.13 |

| Total bilirubin in μmol/L | 23.3 ± 16.7 | 16.5 ± 10.2 | < 0.001 | 22.5 ± 16.3 | 15.7 ± 8.9 | < 0.001 | 29.5 ± 24.0 | 16.3 ± 9.0 | < 0.001 | 15.8 ± 10.5 | 17.2 ± 8.8 | 0.47 |

| Platelets, 109/L | 62.0 ± 37.2 | 105.7 ± 102.4 | 0.009 | 81.8 ± 105.8 | 106.6 ± 95.9 | 0.046 | 81.3 ± 59.2 | 102.7 ± 100.8 | 0.29 | 131.1 ± 109.2 | 90.35 ± 92.1 | 0.05 |

| INR | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | < 0.001 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | < 0.001 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | < 0.001 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.49 |

| Ascites, none/mild/severe | 2/14/2007 | 12/28/68 | 0.03 | 8/21/2008 | 11/22/61 | 0.35 | 1/14/2000 | 19/29/68 | 0.03 | 9/13/2004 | 15/21/69 | 0.25 |

| History of OHE | 13 (56.5) | 41 (38.0) | 0.10 | 17 (45.9) | 37 (39.4) | 0.49 | 12 (80) | 42 (36.2) | 0.001 | 3 (11.5) | 51 (48.6) | 0.001 |

| CPC, A/B/C | 3/18/2 | 37/56/15 | 0.06 | 6/23/8 | 34/51/9 | 0.04 | 7/8/2000 | 40/67/9 | < 0.001 | 3/2/2021 | 19/71/15 | < 0.001 |

| MELD score | 19.6 ± 4.7 | 14.9 ± 4.1 | < 0.001 | 19.2 ± 4.2 | 14.3 ± 3.8 | < 0.001 | 23.3 ± 5.0 | 14.8 ± 3.7 | < 0.001 | 13.7 ± 4.0 | 17.7 ± 6.2 | 0.002 |

| Complications | 23 (100) | 14 (13.0) | < 0.001 | 37 (100) | 0 | < 0.001 | 10 (66.7) | 27 (23.3) | < 0.001 | 0 | 37 (35.2) | < 0.001 |

| OHE | 23 (100) | 0 | < 0.001 | 23 (62.2) | 0 | < 0.001 | 7 (46.7) | 16 (13.8) | 0.002 | 0 | 23 (21.9) | < 0.001 |

| Mortality | 7 (30.4) | 8 (7.4) | 0.002 | 10 (27.0) | 5 (5.3) | < 0.001 | 15 (100) | 0 | < 0.001 | 0 | 15 (14.3) | < 0.001 |

Cox analysis of all the potential parameters (with P values < 0.05 from the univariate analysis shown in Table 2) indicated that only serum albumin < 30 g/L was a predictor for developing OHE. Serum creatinine > 133 μmol/L, MELD score > 20 and blood platelet < 80 × 109/L were predictors for development of the cirrhosis-related complications requiring hospitalization; serum creatinine > 133 μmol/L was the only predictor for mortality of CHE patients (Table 3). After adjusting for age and sex, multivariate logistic analysis showed that CPC-B/C (β: -2.48, HR = 0.084, 95%CI: 0.026-0.264, P < 0.001) and OHE history (β: -1.91, HR = 0.15, 95%CI: 0.03-0.67, P = 0.014) were predictors for CHE SR.

| Predictor(s) | β | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| For developing OHE | Albumin < 30 g/L | 1.65 | 5.22 | 1.22-22.32 | 0.03 |

| For developing the first cirrhosis-related complications | Cr > 133 μmol/L | 1.24 | 3.46 | 1.46-8.20 | 0.005 |

| MELD score > 20 | 2.31 | 10.12 | 4.14-24.74 | < 0.001 | |

| PLT < 80 × 109/L | 2.52 | 2.44 | 1.69-6.60 | 0.013 | |

| For mortality | Cr > 133 μmol/L | 1.51 | 4.75 | 1.10-20.44 | 0.036 |

Until now, no study has explored the real natural history of CHE in the absence of medication intervention. Our study shows that CHE can worsen, persist, or even spontaneously resolve without medication intervention over a 1-year period. Patients with an OHE history, low serum albumin, high serum creatinine, decreased blood platelet count, or poor liver function should be treated to prevent complications and reduce mortality. Patients with CPC-A and without OHE history may be monitored with caution without treatment. It is our speculation that triage of CHE patients based on predictors for exacerbation and resolution, rather than on the degree of impairment in daily work productivity or quality of life, will make clinical management more precise and cost-effective.

There are many testing strategies focusing on paper-pencil abnormalities, computerized or neurophysiological tests, such as PHES, repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status (commonly known as RBANS), inhibitory control test (ICT), EncephalApp Stroop smartphone App, critical flicker frequency (CFF), and electroencephalography (EEG). According to the guidelines, the diagnosis of CHE in multi-center studies should utilize at least two of the current validated testing strategies, consisting of PHES and one of the following: computerized (continuous reaction time, ICT, scan reaction time, or Stroop) or neurophysiological (CFF or EEG).

In single-center or clinical routine studies, investigators should use tests with which they are familiar for assessing the severity of HE, provided that normative reference data are available and the tests have been validated for use in the patient population[1,2]. In this single-center study, we used PHES, which has been previously validated in China[20], to define CHE diagnosis, persistence and resolution. In our study, 35.8% of consecutive clinically stable cirrhotic patients were diagnosed with CHE based on PHES tests, in agreement with previous Chinese studies[7,20].

Only a few studies have discussed risk factors of CHE in cirrhotic patients[23,24]. However, these studies excluded patients with OHE history. As patients with resolved OHE may be at risk for developing CHE, risk factors for patients with OHE history also need to be explored. Yoshimura et al[25] enrolled patients with and without OHE history and revealed that OHE history was strongly associated with CHE, while cirrhosis-related symptom scores were associated with CHE for patients without OHE history, which is similar to our findings.

Several studies have focused on searching for predictors of OHE in cirrhotic patients. A recent study reported that CHE and elevated blood NH3 levels contributed to OHE development in cirrhosis[3]. Another study indicated that OHE history, presence of CHE and an albumin level < 3.5 g/dL were associated with OHE development in cirrhosis[5]. Based on our findings, it is more cost-effective to screen and identify predictors of OHE development in CHE patients rather than in all cirrhotic patients. Our results showed that only serum albumin level < 30 g/L is the predictor for developing OHE in CHE patients. We propose that CHE patients with a low level of serum albumin should be treated rather than being monitored to reduce hospitalizations and mortality.

Several studies have investigated the natural history of CHE[3-5,9-11,13-18]. Recently, five studies showed that CHE is associated with occurrence of OHE and reduced survival rate[9-11,17,18]. Thomsen et al[9] enrolled 106 clinically-stable cirrhotic patients with no previous history of OHE and followed them for 230 ± 95 d. They found that 13.3% of CHE patients (defined by CFF, EEG or PHES) developed OHE, and the survival rate was 86.7%. In a multicenter study by Patidar et al[10], a total of 170 cirrhotic patients were followed for a mean of 13 mo. They found that 30% of cirrhotic patients developed at least one OHE episode, and that CHE, which was defined by PHES only, increased their risk of developing OHE, hospitalization and death/transplant despite controlling for MELD.

A study by Ampuero et al[11] demonstrated that patients with CHE, as defined by CFF, had a reduced 5-year survival rate compared to those without CHE (57.4%-68.6% vs 70%-82%). It also predicted the occurrence of OHE (37.1%-38.9% in patients with CHE vs 18.3%-24.6% in those without CHE). In a multi-center study by Allampati et al[17], a total of 437 cirrhotic patients and 308 controls were followed for 11 mo. The authors reported that 13% of patients developed an episode of OHE, which was predicted by CHE defined by the EncephalApp based on adjusted United States population norms, ICT or PHES.

However, none of the above studies stopped medications used for the treatment of other complications (i.e., antibiotics for infection or significant GVB, albumin transfusion for ascites, lactulose for constipation) during follow-up, which can play important roles in preventing occurrence of OHE and help CHE resolution. Persistence and SR of CHE were also not explored in these studies. Therefore, the real natural course of CHE without medication intervention was not evaluated, and therefore the risk of developing complications and mortality in CHE patients could be underestimated due to the medications used during follow-up. Furthermore, though CHE was reported to be associated with a higher risk of developing complications and reduced survival rate in these studies, it remains to be determined if all CHE patients need to be treated.

Our study revealed that CHE can resolve after 3 mo following the initial diagnosis, or can last as long as 1 year in the absence of medication intervention. Predictors for CHE SR were also explored in our study for the first time. Our data indicated that patients with predictors for SR could be monitored without resorting to medications, and receive appropriate medical support if predictors for development of complications and mortality appeared. Our findings also suggested that CHE patients need to be repeatedly evaluated at appropriate time intervals, as CHE can fluctuate over time.

There are some limitations in our study. Firstly, we conducted a single-center observational study with a relatively short follow-up period. However, we are the first to explore the natural history of CHE without medication intervention with a sample size large enough and time period long enough to identify predictors for exacerbation and SR of CHE. In addition, as cirrhotic patients developed complications over time, fewer patients were free of medications at a longer period of follow-up. Then it was of little significance to explore the natural course of CHE due to the limited number of patients. Secondly, a 3-mo interval between visits was arbitrarily decided by the researchers. As CHE and OHE fluctuate and cognitive changes may be missed by this frequency, shorter intervals of observation would have been more convincing. However, it is our opinion that a 3-mo interval is the minimal time interval to eliminate learning effects for PHES. Thirdly, only some of the medications for treating cirrhosis, including antibacterial agents, lactulose, probiotics, L-ornithine-L-aspartate and albumin, were restricted unless necessary. However, some other medications, such as proton pump inhibitors, diuretics, non-selective beta-blocker and anti-HBV agents, were not restricted during our follow-up, as the potential impact of these agents on CHE is still in debate.

In summary, CHE is prevalent in clinically-stable cirrhotic patients and is associated with an increased risk of complications, hospitalizations and mortality. CHE can evolve into OHE, persist or spontaneously resolve without medication intervention within a short period. Although data are lacking regarding the standard management of CHE in clinical practice, we believe triage of patients based on predictors of exacerbation and improvement of CHE in natural history could make clinical management of CHE more precise and cost-effective.

Covert hepatic encephalopathy (CHE) is regarded as the pre-clinical stage of hepatic encephalopathy (HE). The natural history of CHE in cirrhotic patients in the absence of medication intervention has not yet been studied. The aim of this study was to explore the prevalence and natural history of CHE in clinically-stable cirrhosis in a tertiary care hospital, and to identify predictors for exacerbation and resolution of CHE without medication intervention.

Several studies have investigated the natural history of CHE. Their findings indicate that CHE is prevalent in clinically-stable cirrhotic patients and is associated with an increased risk of complications, hospitalizations and mortality. However, medications treating other cirrhosis complications are not restricted in CHE patients. These agents used during follow-up would treat CHE, hinder the occurrence of other complications, and underestimate the disadvantages of CHE.

The present study indicated that CHE could worsen, persist or even spontaneously resolve without medication intervention over a 1-year period. Serum albumin < 30 g/L was the sole predictor for overt HE (OHE) and blood creatinine > 133 μmol/L predicted mortality. Child-Pugh A classification and absence of OHE history can predict spontaneous resolution of CHE.

To make the clinical management of CHE more precise and cost-effective, patients with an OHE history, low serum albumin, high serum creatinine, decreased blood platelet count or poor liver function should be treated to prevent complications and reduce mortality. Patients with Child-Pugh A classification and those without OHE history may be monitored with caution without treatment. Triage of CHE patients may be based on predictors for exacerbation and resolution rather than on the degree of impairment in daily work productivity or quality of life.

The authors conducted a well-written observational study. The case enrollment and variable choices are appropriate. Despite the fact that this study is a single-center observational study with a relatively short-period follow up, it provides some new insights.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Cubero FG S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, Cordoba J, Ferenci P, Mullen KD, Weissenborn K, Wong P. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60:715-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1583] [Cited by in RCA: 1405] [Article Influence: 127.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 practice guideline by the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. J Hepatol. 2014;61:642-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Iwasa M, Sugimoto R, Mifuji-Moroka R, Hara N, Yoshikawa K, Tanaka H, Factors contributing to the development of overt encephalopathy in liver cirrhosis patients. Metab Brain Dis. 2016;31:1151-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Romero-Gómez M, Boza F, García-Valdecasas MS, García E, Aguilar-Reina J. Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy predicts the development of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2718-2723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Riggio O, Amodio P, Farcomeni A, Merli M, Nardelli S, Pasquale C, Pentassuglio I, Gioia S, Onori E, Piazza N. A Model for Predicting Development of Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients With Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1346-1352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mina A, Moran S, Ortiz-Olvera N, Mera R, Uribe M. Prevalence of minimal hepatic encephalopathy and quality of life in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:E92-E99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang JY, Zhang NP, Chi BR, Mi YQ, Meng LN, Liu YD, Wang JB, Jiang HX, Yang JH, Xu Y. Prevalence of minimal hepatic encephalopathy and quality of life evaluations in hospitalized cirrhotic patients in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4984-4991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Bajaj JS, Hafeezullah M, Franco J, Varma RR, Hoffmann RG, Knox JF, Hischke D, Hammeke TA, Pinkerton SD, Saeian K. Inhibitory control test for the diagnosis of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1591-1600.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Thomsen KL, Macnaughtan J, Tritto G, Mookerjee RP, Jalan R. Clinical and Pathophysiological Characteristics of Cirrhotic Patients with Grade 1 and Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0146076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Patidar KR, Thacker LR, Wade JB, Sterling RK, Sanyal AJ, Siddiqui MS, Matherly SC, Stravitz RT, Puri P, Luketic VA. Covert hepatic encephalopathy is independently associated with poor survival and increased risk of hospitalization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1757-1763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ampuero J, Simón M, Montoliú C, Jover R, Serra MÁ, Córdoba J, Romero-Gómez M. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy and critical flicker frequency are associated with survival of patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1483-1489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Stewart CA, Smith GE. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:677-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | D’Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol. 2006;44:217-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1892] [Cited by in RCA: 2126] [Article Influence: 111.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 14. | Dhiman RK, Kurmi R, Thumburu KK, Venkataramarao SH, Agarwal R, Duseja A, Chawla Y. Diagnosis and prognostic significance of minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis of liver. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2381-2390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hartmann IJ, Groeneweg M, Quero JC, Beijeman SJ, de Man RA, Hop WC, Schalm SW. The prognostic significance of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2029-2034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Das A, Dhiman RK, Saraswat VA, Verma M, Naik SR. Prevalence and natural history of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:531-535. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Allampati S, Duarte-Rojo A, Thacker LR, Patidar KR, White MB, Klair JS, John B, Heuman DM, Wade JB, Flud C. Diagnosis of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy Using Stroop EncephalApp: A Multicenter US-Based, Norm-Based Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:78-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Montagnese S, Balistreri E, Schiff S, De Rui M, Angeli P, Zanus G, Cillo U, Bombonato G, Bolognesi M, Sacerdoti D. Covert hepatic encephalopathy: agreement and predictive validity of different indices. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:15756-15762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ferenci P, Lockwood A, Mullen K, Tarter R, Weissenborn K, Blei AT. Hepatic encephalopathy--definition, nomenclature, diagnosis, and quantification: final report of the working party at the 11th World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna, 1998. Hepatology. 2002;35:716-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1594] [Cited by in RCA: 1406] [Article Influence: 61.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Li SW, Wang K, Yu YQ, Wang HB, Li YH, Xu JM. Psychometric hepatic encephalopathy score for diagnosis of minimal hepatic encephalopathy in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8745-8751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Randolph C, Hilsabeck R, Kato A, Kharbanda P, Li YY, Mapelli D, Ravdin LD, Romero-Gomez M, Stracciari A, Weissenborn K; International Society for Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism (ISHEN). Neuropsychological assessment of hepatic encephalopathy: ISHEN practice guidelines. Liver Int. 2009;29:629-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang JL. Clinical epidemiology. 3rd edition. Shanghai Science & Technology Press; 2009: 165-166. . |

| 23. | Hirano H, Saito M, Yano Y, Momose K, Yoshida M, Tanaka A, Azuma T. Chronic liver disease questionnaire would be a primary screening tool of neuropsychiatric test detecting minimal hepatic encephalopathy of cirrhotic patients. Hepatol Res. 2015; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nabi E, Thacker LR, Wade JB, Sterling RK, Stravitz RT, Fuchs M, Heuman DM, Bouneva I, Sanyal AJ, Siddiqui MS. Diagnosis of covert hepatic encephalopathy without specialized tests. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1384-1389.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yoshimura E, Ichikawa T, Miyaaki H, Taura N, Miuma S, Shibata H, Honda T, Takeshima F, Nakao K. Screening for minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis by cirrhosis-related symptoms and a history of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Biomed Rep. 2016;5:193-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |