Published online Aug 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i32.5913

Peer-review started: April 14, 2017

First decision: June 7, 2017

Revised: June 22, 2017

Accepted: July 22, 2017

Article in press: July 24, 2017

Published online: August 28, 2017

Processing time: 137 Days and 10.3 Hours

To investigate the impact of thymidylate synthase (TYMS), KRAS and BRAF in the survival of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients treated with chemotherapy.

Clinical data were collected retrospectively from records of consecutive patients with mCRC treated with fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy from 1/2005 to 1/2007. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues were retrieved for analysis. TYMS genotypes were identified with restriction fragment analysis PCR, while KRAS and BRAF mutation status was evaluated using real-time PCR assays. TYMS gene polymorphisms of each of the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) and 5’UTR were classified into three groups according to the probability they have for high, medium and low TYMS expression (and similar levels of risk) based on evidence from previous studies. Univariate and multivariate survival analyses were performed.

The analysis recovered 89 patients with mCRC (46.1% de novo metastatic disease and 53.9% relapsed). Of these, 46 patients (51.7%) had colon cancer and 43 (48.3%) rectal cancer as primary. All patients were treated with fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy (5FU or capecitabine) as single-agent or in combination with irinotecan or/and oxaliplatin or/and bevacizumab. With a median follow-up time of 14.8 mo (range 0-119.8), 85 patients (95.5%) experienced disease progression, and 63 deaths (70.8%) were recorded. The 3-year and 5-year OS rate was 25.4% and 7.7% while the 3-year progression-free survival rate was 7.1%. Multivariate analysis of TYMS polymorphisms, KRAS and BRAF with clinicopathological parameters indicated that TYMS 3’UTR polymorphisms are associated with risk for disease progression and death (P < 0.05 and P < 0.03 respectively). When compared to tumors without any del allele (genotypes ins/ins and ins/loss of heterozygosity (LOH) linked with high TYMS expression) tumors with del/del genotype (low expression group) and tumors with ins/del or del/LOH (intermediate expression group) have lower risk for disease progression (HR = 0.432, 95%CI: 0.198-0.946, P < 0.04 and HR = 0.513, 95%CI: 0.287-0.919, P < 0.03 respectively) and death (HR = 0.366, 95%CI: 0.162-0.827, P < 0.02 and HR = 0.559, 95%CI: 0.309-1.113, P < 0.06 respectively). Additionally, KRAS mutation was associated independently with the risk of disease progression (HR = 1.600, 95%CI: 1.011-2.531, P < 0.05). The addition of irinotecan in 1st line chemotherapy was associated independently with lower risk for disease progression and death (HR = 0.600, 95%CI: 0.372-0.969, P < 0.04 and HR = 0.352, 95%CI: 0.164-0.757, P < 0.01 respectively).

The TYMS genotypes ins/ins and ins/LOH associate with worst prognosis in mCRC patients under fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy. Large prospective studies are needed for validation of our findings.

Core tip: The etiology of resistance to new targeted agents and chemotherapy is currently being investigated based upon the patients’ genetic profile in order to develop a prognostic model that could lead to individualized treatment. In this context, we studied the effect of thymidylate synthase (TYMS) polymorphisms that have been described so far, taking into account the presence of KRAS and BRAF mutations in association with the treatment. TYMS 3’ untranslated region polymorphism ins/ins and ins/loss of heterozygosity emerged as an independent factor that increases the risk of both disease progression and death. Regimens that included irinotecan had reduced risk of disease progression and death.

- Citation: Ntavatzikos A, Spathis A, Patapis P, Machairas N, Peros G, Konstantoudakis S, Leventakou D, Panayiotides IG, Karakitsos P, Koumarianou A. Integrating TYMS, KRAS and BRAF testing in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(32): 5913-5924

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i32/5913.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i32.5913

Metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) is the second and third leading cause of cancer-related death in Europe[1] and the United States[2] respectively, although important and constant overall survival (OS) improvements have been achieved[3] in the last decades. Even though today there are more treatment options, including several basic chemotherapy regimens in combination with targeted agents[4], it has been found that large variation exists in individual patient prognosis and response to chemotherapy, caused by molecular heterogeneity[5]. As a result, treatment decisions are more complex and largely empirical[6]. This depicts our lack of understanding of the molecular background and the interplay of different oncogenic pathways, such as RAS and BRAF, with gene polymorphisms, such as thymidylate synthase (TYMS), that can be responsible for the heterogeneity of responses to treatments.

KRAS is a member of the RAS family of genes (KRAS, NRAS and HRAS) that encode quanosine-5’-triphosphate (GTP)-binding proteins, which acts as a molecular switch, linking receptor and non-receptor tyrosine kinase activation to downstream cytoplasmic or nuclear events. Activating mutations in RAS result in stimulating cell proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis. Around 32%-40% of CRC harbor a KRAS mutation[7,8] which is a predictor of response to anti-EGFR treatment[9,10]. BRAF is a KRAS downstream abnormally activated kinase that has been shown to have a similar adverse effect on treatment response[7,8].

The backbone of mCRC chemotherapy are fluoropyrimidines (5-FU and capecitabine) that cause inhibition of de novo thymidine creation from uracil by the TYMS enzyme. Potential resistance mechanisms to fluoropyrimidines include TYMS gene amplification[11], loss of heterozygosity (LOH)[12] and a negative feedback mechanism[13]. The TYMS gene (GeneID 7298[14]) is located on the short arm of chromosome 18 (18p11.32) and several polymorphisms of the TYMS gene have been connected to variable TYMS protein levels and therapeutic outcome in relation to 5-FU.

The first polymorphism has been identified in the 5’ untranslated region (UTR) and includes an insertion of a 28 base-pair (bp) repeat (rs34743033[14]), that adds an extra binding site for the upstream stimulatory factor-1 (USF-1) transcription factor (E-box CACTTG[15]). This USF-1 extra binding site acts as an enhancer to the TYMS promoter which leads to increased TYMS expression and thus to increased TYMS enzyme activity[16]. This results in alleles with two or three 28 bp tandem repeats (2R or 3R respectively). The second polymorphism (rs2853542[14]) is a G>C single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the second 28 bp repeat of 3R alleles that abolishes the extra USF-1 binding site[17] and leads to conversion of the transcriptional activity from a 3R to a 2R. The third polymorphism is located on the 3’UTR (rs34489327[14]) and is a 6 bp insertion linked to stabilization of the mRNA transcript[18,19]. The above polymorphisms produce three genotypes: ins/ins (homozygous for insertion of 6bp), del/del (homozygous for deletion of the 6bp) and ins/del (heterozygous).

This study aims to investigate the associations of TYMS polymorphisms, LOH, KRAS/BRAF mutations and clinicopathologic characteristics with the survival outcomes of patients with mCRC treated with 1st line fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy.

This was a retrospective study carried out by a single institution (University General Hospital “ATTIKON”, Athens, Greece). Clinical data were collected from records of consecutive patients with mCRC treated with fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy from 1/2005 to 1/2007. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues (FFPE) from consecutive patients with mCRC were retrieved for analysis.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethical Committee (University General Hospital “ATTIKON”).

Five 5-μm thick FFPE sections from a site containing at least 30% malignant cells were used for DNA extraction by means of a commercially available kit (Purelink Genomic DNA Kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Schwerte, Germany). DNA was quantified using qPCR (Quant-iT™ PicoGreen® dsDNA Assay Kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and was diluted accordingly to achieve a concentration of 10 ng/μL for TYMS polymorphisms and 4 ng/μL for KRAS mutation detection.

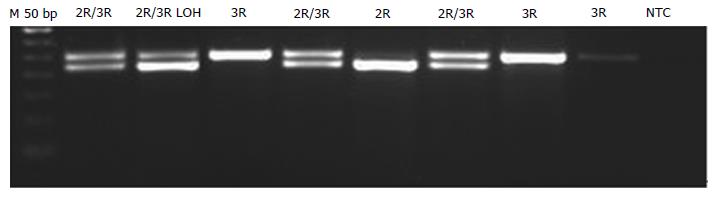

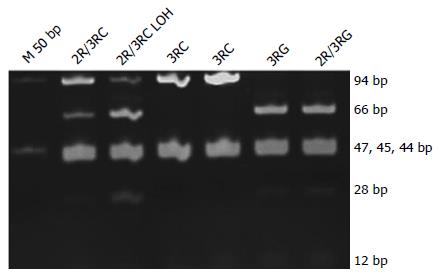

Analysis was performed as previously described with minor modifications[20]. PCR was performed using 1 U of Platinum®Taq DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1.5 mmol/L of Mg, 200 nmol/L of dNTPs, and primers. The same primers were used, but 5’UTR amplification was performed using a GC-rich amplification kit (PCRX Enhancer System; Thermo Fisher Scientific) adding 1 × of PRCx Enhancer. Genotyping for the 2R/3R polymorphism was performed by running 10 μL of the PCR product on a 1.5% agarose gel and staining with EtBr (Figure 1). For the 12 G>C substitution, 10 μL of PCR product was digested with 1 U of HaeIII (Takara, Shiga, Japan) for 1 h at 37 °C and run on an 8% 19:1 polyacrylamide gel (Figure 2).

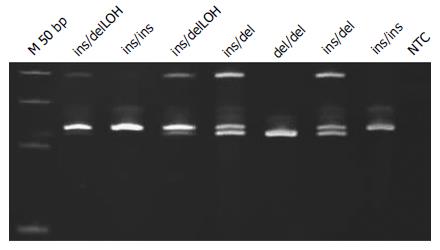

The 3’UTR was also analyzed on polyacrylamide gels (Figure 3). LOH analysis was performed via analyzing the intensity of the 5’UTR and 3’UTR bands on the pictures acquired using GeneTools software (Syngene, Cambridge, United Kingdom) (Figures 1 and 3). When either of the bands had an intensity of < 50% of the other, the sample was categorized as having a LOH. Samples showing LOH were defined as 2R/3RGLOH, 2RLOH/3RG, 2R/3RCLOH and 2RLOH/3RC to indicate the allele that was partially lost. Selected products were sequenced to verify the sequence amplified. Blast of the sequenced products and alignment with the latest human assemblies revealed that the amplified product was 242 bp for 3R and 214 bp for 2R genotypes.

Detection of KRAS mutations of codons 12 and 13 was performed with a commercially available Real-Time (RT) PCR kit (Therascreen KRAS; DxS Diagnostics, Manchester, United Kingdom) detecting six mutations of codon 12 (G12D, G12A, G12V, G12S, G12R, G12C) and one mutation of codon 13 (G13D)[21]. A positive reaction mix for all mutations was included. A second exogenous reaction was simultaneously taking place, to avoid false negative results caused by PCR inhibitors. Samples were characterized as bearing a mutation only if ΔСt (Ct of control reaction - Ct mutation reaction) was lower than the value set by the manufacturer.

The activating mutation V600E of BRAF was identified using molecular beacons, as previously described[21]. One beacon for the wild-type and one for the mutant allele were added at a final concentration of 100 nmol/L in a 25 μL PCR reaction containing 1 × PCR Buffer, 6 mmol/L MgCl2, 200 nmol/L dNTPs, 300 nmol/L of each primer and 1U of Platinum®Taq. The PCR thermocycling profile used was 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 62 °C for 60 s and 72 °C for 20 s. SKMEL2 and SKMEL20 DNA extracts were used as positive controls for both the wild-type and mutant allele (CLS, Germany). All RT-PCR experiments were performed on an ABI 7500 Fast instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Polymorphisms of the TYMS gene in each the 3’UTR and 5’UTR were classified into three groups according to the probability they have for high, medium and low TYMS expression (and similar levels of risk[22]), taking into account the following evidence from previous studies: (1) 3R polymorphism has higher translation efficiency than that of the 2R, leading to higher TYMS protein expression associated with resistance to 5FU-based chemotherapy[18,23], while the 2R/3R has an intermediate TYMS protein expression profile[24]; (2) the SNP G>C results in the 3RC genotype, reported to display a similar transcriptional activity as the 2R genotype (since 3RC and 2R have the same number of binding sites for the USF-1)[17,25]; (3) the 6 bp insertion, located in the 3’UTR of the TYMS primary transcript, favors the TYMS mRNA stability, increasing TYMS protein expression[26] and the possibility of resistance to 5FU[18]; (4) Lower TYMS protein expression leads to higher sensitivity to fluoropyrimidine-based therapy[27,28]; and (5) LOH is associated with a higher risk of resistance to 5FU chemotherapy[12,29]. Genotypes categorized into expression groups are shown in Table 1.

| Low expression | Medium expression | High expression | |

| TYMS 3’UTR | del/del | ins/del | ins/ins |

| del/LOH | ins/LOH | ||

| TYMS 5’UTR | 2RG | 2RG/3RG | 3RG |

| 2RG/3RC | 2RG/3RG | 3RG/3RC | |

| 3RC | 2RG/3RCLOH | 2RGLOH/3RG | |

| 2RG/3RGLOH | |||

| 2RGLOH/3RC |

OS was defined as the time from the initiation of 1st line chemotherapy to the date of death by any cause. Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated as the time from 1st line chemotherapy initiation to the date of verified progression of the disease or the date of death by any cause. Surviving patients were censored at the date of last contact.

The relationship of TYMS polymorphisms groups with OS and PFS was assessed by univariate Cox regression analysis. Time-to-event distributions were estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves. Correlation of TYMS polymorphisms among them and with selected clinicopathological characteristics were performed using the χ2 test. For all correlations, the level of statistical significance was set at P = 0.05.

The Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess the relationship of clinicopathological parameters and the examined polymorphisms with OS and PFS. In the multivariate Cox regression analysis, a backward selection procedure with a removal criterion of P > 0.10 based on likelihood ratio test was performed to identify significant variables among the following: age, sex (female vs male), histological grade (III-IV vs I-II), primary site (rectal vs colon), KRAS and BRAF status, groups of TYMS polymorphisms, existence of LOH, history of relapse or de novo metastatic disease and treatment.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software for Windows (version 24; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States).

Patients’ information including age, sex, primary tumor site, histological grade, treatment and survival are presented in Table 2. The median age was 65 years (range: 27-86), and the primary site was colon or rectum in 46 and 43 patients respectively. De novo metastatic disease was present in 41 patients (46.1%). First-line fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy was administered to 88 patients, with a median number of 6 cycles (range: 1-12). In total, 5FU-based chemotherapy was given to 13 patients (14.6%), while 75 patients (84.3%) received capecitabine-based chemotherapy. Fluoropyrimidine-based regimens were combined with irinotecan (31.4%), oxaliplatin (49.4%) or both drugs (6.7%). Bevacizumab was included in the 1st line treatment of 61 patients (68.5%). With a median follow-up of 14.8 mo (range: 0-119.8), 85 patients (95.5%) experienced disease progression and 63 deaths (70.8%) were recorded. The 3-year and 5-year OS rate was 25.4% and 7.7% respectively, while the 3-year PFS rate was 7.1%.

| Clinicopathologic data | Relapses | De novo metastatic | Total |

| 48 (53.9) | 41 (46.1) | 89 (100) | |

| Age | 65 (40-84.1) | 64 (27-86) | 65 (27-86) |

| Male | 34 (70.8) | 23 (56.1) | 57 (64.8) |

| Primary site | |||

| Colon | 20 (41.7) | 26 (63.4) | 46 (51.7) |

| Rectum | 28 (58.3) | 15 (36.6) | 43 (48.3) |

| Histological grade | |||

| I + II | 27 (56.3) | 28 (68.3) | 55 (61.8) |

| III + IV | 21 (43.7) | 13 (31.7) | 34 (38.2) |

| KRAS mutation | 22 (45.8) | 18 (43.9) | 40 (44.9) |

| BRAF V600E mut | 2 (4.2) | 3 (7.3) | 5 (5.6) |

| TYMS LOH | 15 (31.3) | 11 (26.8) | 26 (29.2) |

| Fluoropyrimidine-based CT | |||

| Monotherapy or with | 5 (10.4) | 5 (12.2) | 10 (11.2) |

| Irinotecan | 18 (37.5) | 10 (24.4) | 28 (31.4) |

| Oxaliplatin | 22 (45.8) | 22 (53.7) | 44 (49.4) |

| Oxaliplatin and irinotecan | 3 (6.3) | 3 (7.3) | 6 (6.7) |

| Bevacizumab | 31 (64.6) | 30 (73.2) | 61 (68.5) |

| No chemotherapy | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (1.1) |

| Overall survival | |||

| Deaths | 30 (62.5) | 33 (80.5) | 63 (70.8) |

| Time1 in mo | 21.4 (12.2-30.6) | 18.2 (14.3-22.0) | 19.8 (15.8-23.9) |

| Progression-free survival | |||

| Events | 44 (91.7) | 41 (100.0) | 85 (95.5) |

| Time1 in mo | 10.8 (9.0-12.5) | 9.9 (7.0-12.8) | 10.6 (8.8-12.5) |

| Follow-up in mo | 14.2 (0-72.5) | 17.0 (0.8-119.8) | 14.8 (0-119.8) |

The detected genotypes of TYMS according to de novo metastatic or relapsed patients are shown in Supplemental Table 1. The wide variations deriving from TYMS polymorphism combinations and the presence of LOH according to de novo metastatic and relapsed patients are shown in Supplemental Table 2. The 3’UTR polymorphisms had no association with the 5’UTR polymorphism or the SNP G>C. The ins alleles correlated almost statistically significantly with LOH, as shown in Supplemental Table 3.

Analysis of significant association of TYMS polymorphisms with patient and tumor characteristics is shown in Table 3. Younger patients (< 65 years old) were more frequently found to carry 2R, but not in a statistically significant way. Also, low grade tumors (I, II) associated with 2RG/3RG (P < 0.05). The absence of mutations in KRAS correlated with 3RG/3RC (P < 0.04).

| Polymorphism | Characteristic | RR (95%CI) | P value |

| 2R | Age < 65-years-old | 1.708 (1.158-2.520) | 0.090 |

| 2RG/3RG | Grade 1-2 | 1.449 (1.077-1.948) | 0.044 |

| 2RG/3RC | Female | 1.943 (1.152-3.275) | 0.036 |

| ins/ins | KRAS G12D | 3.563 (1.163-10.912) | 0.045 |

| 3RG/3RC | KRAS wild-type | 1.753 (1.156-2.657) | 0.031 |

Analysis of patients according to TYMS expression groups and genotypes are shown in Table 4. Univariate Cox regression analysis of clinicopathological parameters in relation to PFS and OS showed no significant association in our set of data. Univariate Cox regression analyses of TYMS polymorphisms and groups, KRAS and BRAF mutations and LOH are shown in Table 5. The univariate analysis of TYMS 3’UTR polymorphisms and LOH demonstrated a trend of lower risk for disease progression and death for the genotypes del/del, ins/del and even ins/LOH compared with ins/ins. There is a trend for increased risk of death for patients with KRAS mutation. The analysis of TYMS 5’UTR polymorphisms, whether taking into consideration the SNP G>C and LOH or not, also showed no significant effect.

| Group | Relapsed | De novo metastatic | Total |

| TYMS 5’UTR | |||

| Low expression | |||

| 2RG | 2 (4.2) | 6 (14.6) | 8 (9.0) |

| 2RG/3RC | 8 (16.7) | 3 (7.3) | 11 (12.4) |

| 3RC | 6 (12.5) | 5 (12.2) | 11 (12.4) |

| Medium expression | |||

| 2RG/3RG | 4 (8.3) | 4 (9.8) | 8 (9) |

| 2RG/3RCLOH | 7 (14.6) | 3 (7.3) | 10 (11.2) |

| 2RG/3RGLOH | 3 (6.3) | 2 (4.9) | 5 (5.6) |

| 2RGLOH/3RC | 1 (2.1) | 2 (4.9) | 3 (3.4) |

| High expression | |||

| 3RG | 4 (8.3) | 4 (9.8) | 8 (9.0) |

| 3RG/3RC | 9 (18.8) | 8 (19.5) | 17 (19.1) |

| 2RGLOH/3RG | 4 (8.3) | 4 (9.8) | 8 (9.0) |

| TYMS 3’UTR | |||

| Low expression | |||

| del/del | 6 (12.5) | 7 (17.1) | 13 (14.6) |

| Medium expression | |||

| ins/del | 19 (39.6) | 10 (24.4) | 29 (32.6) |

| del/LOH | 1 (2.1) | 3 (7.3) | 4 (4.5) |

| High expression | |||

| ins/ins | 8 (16.7) | 13 (31.7) | 21 (23.6) |

| ins/LOH | 14 (29.2) | 8 (19.5) | 22 (24.7) |

| Variable | PFS | OS | ||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| KRAS mutated | 1.390 | 0.895-2.164 | 0.142 | 1.669 | 0.996-2.797 | 0.052 |

| BRAF V600E | 0.884 | 0.356-2.196 | 0.791 | 1.514 | 0.545-4.207 | 0.426 |

| LOH | 1.013 | 0.632-1.624 | 0.957 | 1.020 | 0.592-1.758 | 0.944 |

| TYMS 5’UTR | 0.561 | 0.845 | ||||

| 2R | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| 2R/3R | 1.243 | 0.616-2.508 | 0.543 | 1.276 | 0.556-2.928 | 0.565 |

| 3R | 0.974 | 0.474-2.003 | 0.944 | 1.239 | 0.535-2.870 | 0.616 |

| TYMS 5’UTR | 0.887 | 0.486 | ||||

| 2RG | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| 2RG/3RC | 1.151 | 0.535-2.475 | 0.720 | 0.978 | 0.388-2.468 | 0.963 |

| 2RG/3RG | 1.351 | 0.625-2.921 | 0.444 | 1.688 | 0.689-4.132 | 0.252 |

| 3RC | 1.038 | 0.428-2.517 | 0.935 | 0.876 | 0.293-2.620 | 0.813 |

| 3RG/3RC | 0.883 | 0.391-1.995 | 0.764 | 1.648 | 0.660-4.113 | 0.284 |

| 3RG | 1.107 | 0.433-2.832 | 0.832 | 1.054 | 0.348-3.189 | 0.926 |

| TYMS 5’UTR | 0.726 | 0.562 | ||||

| 2R | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| 2RG/3RC | 1.864 | 0.738-4.713 | 0.188 | 1.678 | 0.546-5.160 | 0.366 |

| 2RG/3RCLOH | 0.783 | 0.300-2.044 | 0.617 | 1.044 | 0.328-3.323 | 0.942 |

| 2RG/3RG | 1.058 | 0.372-3.014 | 0.916 | 1.869 | 0.537-6.504 | 0.325 |

| 2RG/3RGLOH | 1.936 | 0.630-5.948 | 0.248 | 3.875 | 1.019-14.740 | 0.047 |

| 2RGLOH/3RC | 1.155 | 0.301-4.441 | 0.834 | 1.091 | 0.126-9.412 | 0.937 |

| 2RGLOH/3RG | 1.656 | 0.617-4.442 | 0.317 | 1.745 | 0.546-5.576 | 0.348 |

| 3RC | 1.096 | 0.428-2.806 | 0.848 | 1.070 | 0.325-3.521 | 0.912 |

| 3RG | 1.163 | 0.432-3.134 | 0.765 | 1.281 | 0.385-4.270 | 0.687 |

| 3RG/3RC | 1.001 | 0.413-2.426 | 0.998 | 2.144 | 0.758-6.064 | 0.151 |

| TYMS 5’UTR groups | 0.812 | 0.489 | ||||

| Low expression | 1.063 | 0.633-1.784 | 0.818 | 0.696 | 0.384-1.261 | 0.232 |

| Medium expression | 0.888 | 0.518-1.523 | 0.667 | 0.851 | 0.460-1.572 | 0.606 |

| High expression | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| TYMS 3’UTR | 0.295 | 0.340 | ||||

| del/del | 0.602 | 0.305-1.190 | 0.144 | 0.563 | 0.259-1.224 | 0.147 |

| ins/del | 0.764 | 0.475-1.228 | 0.267 | 0.910 | 0.522-1.587 | 0.739 |

| ins/ins | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| TYMS 3’UTR | 0.067 | 1 | 0.095 | |||

| del/del | 0.421 | 0.194-0.912 | 0.028 | 0.311 | 0.125-0.772 | 0.012 |

| del/LOH | 0.784 | 0.263-2.334 | 0.662 | 0.773 | 0.175-3.417 | 0.734 |

| ins/del | 0.438 | 0.240-0.802 | 0.007 | 0.459 | 0.230-0.918 | 0.028 |

| ins/LOH | 0.516 | 0.274-0.973 | 0.041 | 0.488 | 0.233-1.020 | 0.057 |

| ins/ins | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| TYMS 3’UTR groups | 0.225 | 0.187 | ||||

| Low expression | 0.639 | 0.323-1.263 | 0.198 | 0.503 | 0.230-1.102 | 0.086 |

| Medium expression | 0.435 | 0.435-1.118 | 0.135 | 0.738 | 0.426-1.279 | 0.279 |

| High expression | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

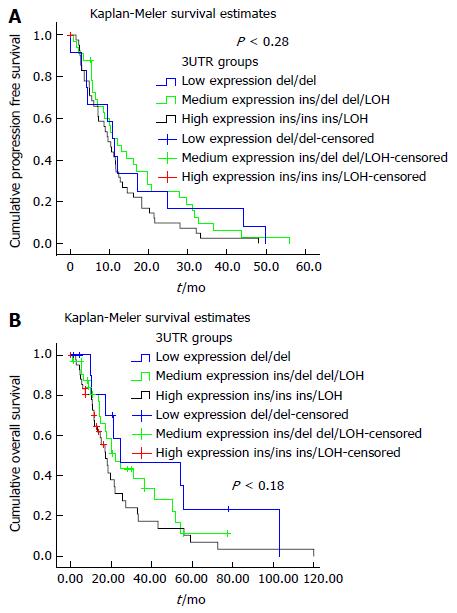

Multivariate analysis of TYMS polymorphism groups and selected clinicopathological parameters is shown in Table 6. KRAS mutation, existence of LOH and the group of TYMS polymorphisms ins/LOH - ins/ins were associated with increased risk for disease progression, while the addition of irinotecan in the 1st line chemotherapy was associated with lower risk. In terms of OS, the group of TYMS polymorphisms ins/LOH - ins/ins was associated with increased statistical risk both of disease progression and death. Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS and OS according to TYMS 3’UTR polymorphisms groups are shown in Figure 4A and B respectively. Furthermore, the addition of irinotecan or oxaliplatin to fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy was associated with lower risk of death. Also, a statistical trend for a higher risk of death was shown in male patients. These findings were consistent in multivariate Cox regression analysis when the history of relapse or de novo metastatic disease was considered.

| PFS | OS | |||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| KRAS mutated | 1.600 | 1.011-2.531 | 0.045 | |||

| LOH | 1.674 | 0.912-3.071 | 0.096 | |||

| Fluoropyrimidine-based CT | ||||||

| With irinotecan | 0.600 | 0.372-0.969 | 0.037 | 0.352 | 0.164-0.757 | 0.007 |

| Without irinotecan | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| With oxaliplatin | 1.000 | |||||

| Without oxaliplatin | 2.702 | 1.273-5.738 | 0.010 | |||

| TYMS 3’UTR groups | 0.043 | 0.027 | ||||

| Low expression | 0.432 | 0.198-0.946 | 0.036 | 0.366 | 0.162-0.827 | 0.016 |

| Medium expression | 0.513 | 0.287-0.919 | 0.025 | 0.559 | 0.309-1.013 | 0.055 |

| High expression | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Males | 1.580 | 0.916-2.724 | 0.100 | |||

This is a retrospective study of 89 patients with mCRC treated with fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy, interrogating the association of TYMS polymorphisms, LOH, KRAS/BRAF status with survival outcome. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that TYMS genotype, LOH and mutations in KRAS and BRAF have been analyzed in relation to the chemotherapy treatment and survival outcome of patients with mCRC. We report that the polymorphisms of the TYMS 3’UTR represent an independent factor, increasing the risk for both disease progression and death of mCRC patients under fluoropyrimidines-based treatment as monotherapy or in combination with oxaliplatin or/and irinotecan, or/and targeted therapy. Also, an independent factor decreasing the risk of both disease progression and death was the administration of fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy in combination with irinotecan, while the combination of fluoropyrimidines with oxaliplatin was associated with lower risk of death.

In search of prognostic markers towards personalized therapy, studies have investigated TYMS gene polymorphisms[30,31], TYMS mRNA expression[32,33] and TYMS protein expression[34-38]/activity[39]. Such studies have conflicting results for the way TYMS polymorphisms seem to affect the therapeutic result in CRC patients[30,36,38,40-46]. The numerous TYMS polymorphisms and their combination could explain the inconclusive results. For example, the SNP G>C was not considered for many years until its discovery[15,17,19]. Thus, the homozygous 3R group was considered to be related with high expression[15] and could include three subgroups with a different impact in TYMS expression (low expression subgroup 3RC/3RC and high expression subgroups 3RG/3RG and 3RG/3RC[24,28]).

Our results indicate that only 8 (21.6%) out of 37 tumors with the 3R polymorphism are 3RG, without the presence either of LOH or SNP G>C. Similarly, 21 (50%) out of 42 heterozygous 2R/3R tumors are 2RG/3RG. The different distribution of these subgroups in various studies could explain the differential effect on survival. Moreover, another factor held responsible for generating inconclusive results is the addition to fluoropyrimidines of newer chemotherapeutics and targeted agents[28] which incommode the interpretation of how TYMS polymorphisms influence survival outcome across different treatment populations. Moreover, there are other genes, such as p53[47], astrocyte elevated gene-1[48], and enolase superfamily member 1[49] that have been proven to participate in the final level of TYMS expression[18,47-50]. Thus, the rather small size samples used in most studies could not examine thoroughly the plethora of all these factors and possible interactions among them, without conflicting results.

Another reason responsible for conflicting results across studies is the categorization of TYMS polymorphisms into only two groups[18,51], which leads to misclassifying polymorphisms with uncertain effect. Although such a classification model is preferred because it facilitates statistical processing (e.g., by increasing the size of each group) and the interpretation of statistical processing, it also entails the risk of increasing the probability of classification error.

Different to previous studies[30,31,50-53], ours took into consideration the extensive number of TYMS polymorphisms, as well as their combinations with LOH and KRAS / BRAF mutations. Additionally, for the first time, we classified the polymorphisms of each UTR region into three groups according to the level of TYMS expression.

The low expression group of 5’UTR polymorphism includes tumors with two alleles, each with one being an active USF-1 binding site. Members of the high expression group have no 2RG allele and they include heterozygous tumors in which, due to LOH, the allele 2RG was deleted. Medium expression group includes the heterozygous tumors with three USF-1 binding sites (one in the 2RG and two in the 3RG), resulting in one more than the low expression and one less than the high expression group. Also in this group, we included tumors with only one 2R allele, as LOH eliminates the 3R allele. Although they have less than three USF-1 binding sites, the LOH situation bears a loss of genetic material from chromosome 18q that, in ways not fully understood, adversely affects survival[54].

The low expression group of 3’UTR polymorphism contains the homozygous deletion of the 6 bp insertion that leads to destabilization of TYMS mRNA, resulting in reduced translation and eventually reduced TYMS activity. The high expression group has only ins alleles, homozygous or in combination with LOH, which impart stability to TYMS mRNA and thus, by increasing TYMS production/activity, increases the risk of poor response or development of resistance[18,19]. Tumors in the medium expression group have an allele with deletion, which coexists with either ins allele or LOH, that have been associated with increased risk of relapse[54].

On the basis of previous studies, TYMS 5’UTR may be linked to survival outcomes[41,55]. Contrary to these, in the multivariate Cox regression analysis of our data, the groups of 5’UTR polymorphisms did not emerge as factors of survival outcome. However, the 3’UTR polymorphisms’ groups, were identified as independent factors of disease progression and death.

More specifically, the high expression group was identified as an independent risk factor of disease progression and death compared to the medium/low-risk groups (Table 5). Similar to our findings, a previous study showed that mCRC patients with del/del genotype treated with 5FU/oxaliplatin had significantly longer OS[31]. The ins allele, present in high-risk genotypes (ins/ins and ins/LOH) has been associated with higher TYMS mRNA stability and TYMS protein expression[18]. It is logical to assume that the mRNA stability has a more significant role in TYMS protein production than the number of transcripts. Hence, even if TYMS 5’UTR has a 3RG polymorphism leading to higher mRNA production, the complete absence of ins allele in TYMS 3’UTR could cause TYMS mRNA instability and therefore decreased TYMS translation. On the contrary, in theory the final outcome of decreased mRNA production of 2R cases combined with ins/ins genotype could be an increase of protein production due to the stability of transcribed mRNA and translational efficacy.

Tumors with 2R/3RLOH genotype have been shown to be expressing significantly lower levels of TYMS protein than those with 2RLOH/3R[56]. Also, patients with mCRC bearing 2R/3RLOH genotype have been shown to have better survival than those with 2RLOH/3R[12]; although in the later study the SNP G>C was not taken into consideration. LOH is as likely to lead to altered genotypes, either with high or low TYMS protein expression (2RLOH/3RG and 2R/3RGLOH respectively). But the loss of chromosomal material from 18q, the cause of LOH, has been shown to act as a molecular marker of adverse prognosis[29], even if combined with the low-risk 2R allele. This is in agreement with our results as LOH remained in the Cox proportional hazards model as a factor that associates with disease progression with marginal statistical significance (HR = 1.674, 95%CI: 0.912-3.071, P < 0.1). This association was not observed for risk of death, probably due to the numerous factors that affect this outcome, such as the additional chemotherapy lines.

It has been previously shown that patients with KRAS mutant tumors had significantly lower TYMS mRNA levels, especially in proximal colon tumors[57]. In our study, we were able to identify an association of KRAS wild-type only with polymorphism 3RG/3RC (RR = 1.753, 95%CI: 1.156-2.657, P < 0.04), a member of the high TYMS protein expression group.

The addition of bevacizumab in the fluoropyrimidine-based 1st line chemotherapy for mCRC did not emerge, in the Cox model, as a factor affecting survival outcome in our study. To date, no prospectively validated biomarkers have emerged to include or exclude patients from anti-VEGF therapy[58]. Pander et al[59] have shown that there is a genetic interaction between the polymorphisms in the TYMS enhancer region (5’UTR) and VEGF +405g>c polymorphisms as a predictor of the efficacy of capecitabine/oxaliplatin/bevacizumab in mCRC patients, but only for PFS. Also, Watanabe et al[60] have found that higher TYMS levels are associated with an adverse response to bevacizumab therapy. In this context, it could be proposed that in studies applying anti-VEGF and targeted therapy, TYMS polymorphisms should be considered. Overall, there is great need for a prognostication model that would include all these polymorphisms with RAS mutations for treatment tailoring.

In our study, we did not examine TYMS protein expression, as this could be affected by a plentitude of factors[47,48,50] and altered in the course of the disease. For example, discordance in TYMS mRNA expression and TYMS protein levels has been found between primary and secondary tumors[33,61,62]. Also, in an autoregulatory manner, the binding of TYMS protein to its own mRNA, as well as the binding of TYMS to p53 mRNA, causes translational repression[13,63,64].

Some limitations of this study should be addressed. The plethora of genotypes resulting from the polymorphisms occurring in the UTRs of TYMS is difficult to be analyzed with a small patient group. Moreover, previous exposure to adjuvant therapy with fluoropyrimidines, that could associate with resistance to fluoropyrimidines, was not taken into consideration. The allocation of TYMS polymorphisms into groups was based on published research but the conflicting results observed in these studies and ours highlight the need for further analysis on larger scale datasets. Also, we did not examine the TYMS protein expression and activity. Finally, due to the retrospective nature of this analysis we could not correlate these findings to the treatment toxicity.

After taking into account the SNP G>C and LOH, only the polymorphisms in the TYMS 3’UTR, affecting the stability of mRNA, independently influenced survival outcome for patients with mCRC treated with fluoropyrimidines-based chemotherapy. Genotypes that include del alleles, linked to TYMS mRNA instability, had better survival outcome. KRAS mutation was associated with high risk of disease progression. Combinations that included irinotecan were associated with lower risk of disease progression and death. Future studies should focus on gathering large samples and carefully selecting batteries of biomarkers to be examined in multivariate analysis. For the more complete assessment of the effect of TYMS gene polymorphisms, LOH should be considered. Further prospective studies are needed to elucidate the role of TYMS polymorphisms in tailoring treatment of patients with mCRC.

Metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) remains a significant cause of cancer-related death worldwide, although important improvements have been achieved in the last decades. It has been found that large variation exists in individual patient prognosis and response to chemotherapy, caused by molecular heterogeneity. Around 32%-40% of CRC harbor a KRAS mutation, which is a predictor of response to anti-EGFR treatment, while BRAF is a KRAS downstream abnormally activated kinase that has been shown to have similar adverse effects on treatment response. Several polymorphisms of the thymidylate synthase (TYMS) gene have been connected to variable TYMS protein levels and therapeutic outcome in relation to 5-FU, while loss of heterozygosity (LOH) is included in potential resistance mechanisms to fluoropyrimidines. This study aimed to investigate the associations of TYMS polymorphisms, LOH, KRAS/BRAF mutations and clinicopathologic characteristics with the survival outcome of patients with mCRC treated with 1st line fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study that analyzes the extensive number of TYMS polymorphisms, particularly their combination with LOH and KRAS and BRAF mutations in relation to the chemotherapy treatment and the survival outcome of patients with mCRC. Additionally, for the first time, the authors classified the polymorphisms of each untranslated region (UTR) into three groups according to the level of TYMS expression. The results of this study contribute to clarifying the significance of TYMS polymorphisms for patients with mCRC.

In this study, the groups of TYMS 5’UTR polymorphisms did not emerge as factors of survival outcome. However, the 3’UTR polymorphisms’ groups were identified as independent factors of disease progression and death. Genotypes that included del alleles, linked to TYMS mRNA instability, had better survival outcome.

This study suggests that TYMS 3’UTR polymorphisms independently influence survival outcome for patients with mCRC treated with fluoropyrimidines-based chemotherapy. Genotypes that include del alleles may benefit from fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy. Future studies should gather large sample sets and carefully select the biomarkers to be examined in multivariate analysis, taking into consideration LOH.

UTR: Regions of the mRNA that are not translated into protein but, among other things, affect the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression. Upstream stimulatory factor: Factors that enhance the gene promoter and lead to increased gene expression.

Good overview of the role of TYMS in the treatment protocol. Will be of interest to the readership.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Greece

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chetty R S- Editor: Yuan Qi L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JW, Comber H, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1374-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3526] [Cited by in RCA: 3659] [Article Influence: 304.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12135] [Cited by in RCA: 12991] [Article Influence: 1443.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Rossi A, Torri V, Garassino MC, Porcu L, Galetta D. The impact of personalized medicine on survival: comparisons of results in metastatic breast, colorectal and non-small-cell lung cancers. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:485-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Peeters M, Price T. Biologic therapies in the metastatic colorectal cancer treatment continuum--applying current evidence to clinical practice. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:397-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sinicrope FA, Okamoto K, Kasi PM, Kawakami H. Molecular Biomarkers in the Personalized Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:651-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cubillo A, Rodriguez-Pascual J, López-Ríos F, Plaza C, García E, Álvarez R, de Vicente E, Quijano Y, Hernando O, Rubio C. Phase II Trial of Target-guided Personalized Chemotherapy in First-line Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39:236-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Adjei AA. Blocking oncogenic Ras signaling for cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1062-1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 614] [Cited by in RCA: 618] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | De Roock W, De Vriendt V, Normanno N, Ciardiello F, Tejpar S. KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, and PTEN mutations: implications for targeted therapies in metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:594-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 417] [Cited by in RCA: 466] [Article Influence: 31.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Allegra CJ, Jessup JM, Somerfield MR, Hamilton SR, Hammond EH, Hayes DF, McAllister PK, Morton RF, Schilsky RL. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: testing for KRAS gene mutations in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma to predict response to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2091-2096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 893] [Cited by in RCA: 895] [Article Influence: 55.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Láng I, Folprecht G, Nowacki MP, Cascinu S, Shchepotin I, Maurel J, Cunningham D, Tejpar S. Cetuximab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: updated analysis of overall survival according to tumor KRAS and BRAF mutation status. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2011-2019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1314] [Cited by in RCA: 1452] [Article Influence: 103.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang TL, Diaz LA Jr, Romans K, Bardelli A, Saha S, Galizia G, Choti M, Donehower R, Parmigiani G, Shih IeM, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Lengauer C, Velculescu VE. Digital karyotyping identifies thymidylate synthase amplification as a mechanism of resistance to 5-fluorouracil in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3089-3094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Uchida K, Hayashi K, Kawakami K, Schneider S, Yochim JM, Kuramochi H, Takasaki K, Danenberg KD, Danenberg PV. Loss of heterozygosity at the thymidylate synthase (TS) locus on chromosome 18 affects tumor response and survival in individuals heterozygous for a 28-bp polymorphism in the TS gene. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:433-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chu E, Koeller DM, Casey JL, Drake JC, Chabner BA, Elwood PC, Zinn S, Allegra CJ. Autoregulation of human thymidylate synthase messenger RNA translation by thymidylate synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8977-8981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | National Center for Biotechnology Information USNLoM. 2017. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed. |

| 15. | Kawakami K, Salonga D, Park JM, Danenberg KD, Uetake H, Brabender J, Omura K, Watanabe G, Danenberg PV. Different lengths of a polymorphic repeat sequence in the thymidylate synthase gene affect translational efficiency but not its gene expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:4096-4101. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Marsh S. Thymidylate synthase pharmacogenetics. Invest New Drugs. 2005;23:533-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mandola MV, Stoehlmacher J, Muller-Weeks S, Cesarone G, Yu MC, Lenz HJ, Ladner RD. A novel single nucleotide polymorphism within the 5’ tandem repeat polymorphism of the thymidylate synthase gene abolishes USF-1 binding and alters transcriptional activity. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2898-2904. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Mandola MV, Stoehlmacher J, Zhang W, Groshen S, Yu MC, Iqbal S, Lenz HJ, Ladner RD. A 6 bp polymorphism in the thymidylate synthase gene causes message instability and is associated with decreased intratumoral TS mRNA levels. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14:319-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ulrich CM, Bigler J, Velicer CM, Greene EA, Farin FM, Potter JD. Searching expressed sequence tag databases: discovery and confirmation of a common polymorphism in the thymidylate synthase gene. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:1381-1385. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Lecomte T, Ferraz JM, Zinzindohoué F, Loriot MA, Tregouet DA, Landi B, Berger A, Cugnenc PH, Jian R, Beaune P. Thymidylate synthase gene polymorphism predicts toxicity in colorectal cancer patients receiving 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5880-5888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Spathis A, Georgoulakis J, Foukas P, Kefala M, Leventakos K, Machairas A, Panayiotides I, Karakitsos P. KRAS and BRAF mutation analysis from liquid-based cytology brushings of colorectal carcinoma in comparison with formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:1969-1975. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Popat S, Matakidou A, Houlston RS. Thymidylate synthase expression and prognosis in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:529-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wang Y, Shen L, Xu N, Wang JW, Jiao SC, Liu ZY, Xu JM. UGT1A1 predicts outcome in colorectal cancer treated with irinotecan and fluorouracil. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6635-6644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hur H, Kang J, Kim NK, Min BS, Lee KY, Shin SJ, Keum KC, Choi J, Kim H, Choi SH. Thymidylate synthase gene polymorphism affects the response to preoperative 5-fluorouracil chemoradiation therapy in patients with rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:669-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kawakami K, Watanabe G. Identification and functional analysis of single nucleotide polymorphism in the tandem repeat sequence of thymidylate synthase gene. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6004-6007. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Stoehlmacher J, Goekkurt E, Mogck U, Aust DE, Kramer M, Baretton GB, Liersch T, Ehninger G, Jakob C. Thymidylate synthase genotypes and tumour regression in stage II/III rectal cancer patients after neoadjuvant fluorouracil-based chemoradiation. Cancer Lett. 2008;272:221-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Qiu LX, Tang QY, Bai JL, Qian XP, Li RT, Liu BR, Zheng MH. Predictive value of thymidylate synthase expression in advanced colorectal cancer patients receiving fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy: evidence from 24 studies. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2384-2389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Panczyk M. Pharmacogenetics research on chemotherapy resistance in colorectal cancer over the last 20 years. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9775-9827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Azzoni C, Bottarelli L, Cecchini S, Ziccarelli A, Campanini N, Bordi C, Sarli L, Silini EM. Role of topoisomerase I and thymidylate synthase expression in sporadic colorectal cancer: associations with clinicopathological and molecular features. Pathol Res Pract. 2014;210:111-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Graziano F, Ruzzo A, Loupakis F, Santini D, Catalano V, Canestrari E, Maltese P, Bisonni R, Fornaro L, Baldi G. Liver-only metastatic colorectal cancer patients and thymidylate synthase polymorphisms for predicting response to 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:716-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kumamoto K, Ishibashi K, Okada N, Tajima Y, Kuwabara K, Kumagai Y, Baba H, Haga N, Ishida H. Polymorphisms of GSTP1, ERCC2 and TS-3’UTR are associated with the clinical outcome of mFOLFOX6 in colorectal cancer patients. Oncol Lett. 2013;6:648-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Grimminger PP, Shi M, Barrett C, Lebwohl D, Danenberg KD, Brabender J, Vigen CL, Danenberg PV, Winder T, Lenz HJ. TS and ERCC-1 mRNA expressions and clinical outcome in patients with metastatic colon cancer in CONFIRM-1 and -2 clinical trials. Pharmacogenomics J. 2012;12:404-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kumamoto K, Kuwabara K, Tajima Y, Amano K, Hatano S, Ohsawa T, Okada N, Ishibashi K, Haga N, Ishida H. Thymidylate synthase and thymidine phosphorylase mRNA expression in primary lesions using laser capture microdissection is useful for prediction of the efficacy of FOLFOX treatment in colorectal cancer patients with liver metastasis. Oncol Lett. 2012;3:983-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Abdallah EA, Fanelli MF, Buim ME, Machado Netto MC, Gasparini Junior JL, Souza E Silva V, Dettino AL, Mingues NB, Romero JV, Ocea LM. Thymidylate synthase expression in circulating tumor cells: a new tool to predict 5-fluorouracil resistance in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:1397-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Paré L, Marcuello E, Altés A, del Rio E, Sedano L, Barnadas A, Baiget M. Transcription factor-binding sites in the thymidylate synthase gene: predictors of outcome in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin? Pharmacogenomics J. 2008;8:315-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yamagishi S, Shimada H, Ishikawa T, Fujii S, Tanaka K, Masui H, Yamaguchi S, Ichikawa Y, Togo S, Ike H. Expression of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, thymidylate synthase, p53 and p21 in metastatic liver tumor from colorectal cancer after 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:1237-1242. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Hosokawa A, Yamada Y, Shimada Y, Muro K, Hamaguchi T, Morita H, Araake M, Orita H, Shirao K. Prognostic significance of thymidylate synthase in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who receive protracted venous infusions of 5-fluorouracil. Int J Clin Oncol. 2004;9:388-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Johnston PG, Benson AB 3rd, Catalano P, Rao MS, O’Dwyer PJ, Allegra CJ. Thymidylate synthase protein expression in primary colorectal cancer: lack of correlation with outcome and response to fluorouracil in metastatic disease sites. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:815-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Umekita N, Tanaka S, Abe H, Kitamura M. [Thymidylate synthase and dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activity in a metastatic liver tumor from colorectal cancer]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2000;27:1883-1885. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Chen Y, Yi C, Liu L, Li B, Wang Y, Wang X. Thymidylate synthase expression and prognosis in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of colorectal cancer survival data. Int J Biol Markers. 2012;27:e203-e211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Dotor E, Cuatrecases M, Martínez-Iniesta M, Navarro M, Vilardell F, Guinó E, Pareja L, Figueras A, Molleví DG, Serrano T. Tumor thymidylate synthase 1494del6 genotype as a prognostic factor in colorectal cancer patients receiving fluorouracil-based adjuvant treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1603-1611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Edler D, Glimelius B, Hallström M, Jakobsen A, Johnston PG, Magnusson I, Ragnhammar P, Blomgren H. Thymidylate synthase expression in colorectal cancer: a prognostic and predictive marker of benefit from adjuvant fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1721-1728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Etienne-Grimaldi MC, Bennouna J, Formento JL, Douillard JY, Francoual M, Hennebelle I, Chatelut E, Francois E, Faroux R, El Hannani C. Multifactorial pharmacogenetic analysis in colorectal cancer patients receiving 5-fluorouracil-based therapy together with cetuximab-irinotecan. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:776-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Johnston PG, Lenz HJ, Leichman CG, Danenberg KD, Allegra CJ, Danenberg PV, Leichman L. Thymidylate synthase gene and protein expression correlate and are associated with response to 5-fluorouracil in human colorectal and gastric tumors. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1407-1412. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Koumarianou A, Tzeveleki I, Mekras D, Eleftheraki AG, Bobos M, Wirtz R, Fountzilas E, Valavanis C, Xanthakis I, Kalogeras KT. Prognostic markers in early-stage colorectal cancer: significance of TYMS mRNA expression. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:4949-4962. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Ichikawa W, Uetake H, Shirota Y, Yamada H, Nishi N, Nihei Z, Sugihara K, Hirayama R. Combination of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase and thymidylate synthase gene expressions in primary tumors as predictive parameters for the efficacy of fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:786-791. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Nief N, Le Morvan V, Robert J. Involvement of gene polymorphisms of thymidylate synthase in gene expression, protein activity and anticancer drug cytotoxicity using the NCI-60 panel. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:955-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Yoo BK, Gredler R, Vozhilla N, Su ZZ, Chen D, Forcier T, Shah K, Saxena U, Hansen U, Fisher PB. Identification of genes conferring resistance to 5-fluorouracil. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:12938-12943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Rosmarin D, Palles C, Church D, Domingo E, Jones A, Johnstone E, Wang H, Love S, Julier P, Scudder C. Genetic markers of toxicity from capecitabine and other fluorouracil-based regimens: investigation in the QUASAR2 study, systematic review, and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1031-1039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Vignoli M, Nobili S, Napoli C, Putignano AL, Morganti M, Papi L, Valanzano R, Cianchi F, Tonelli F, Mazzei T. Thymidylate synthase expression and genotype have no major impact on the clinical outcome of colorectal cancer patients treated with 5-fluorouracil. Pharmacol Res. 2011;64:242-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Joerger M, Huitema AD, Boot H, Cats A, Doodeman VD, Smits PH, Vainchtein L, Rosing H, Meijerman I, Zueger M. Germline TYMS genotype is highly predictive in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal malignancies receiving capecitabine-based chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2015;75:763-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Fernández-Contreras ME, Sánchez-Hernández JJ, González E, Herráez B, Domínguez I, Lozano M, García De Paredes ML, Muñoz A, Gamallo C. Combination of polymorphisms within 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions of thymidylate synthase gene modulates survival in 5 fluorouracil-treated colorectal cancer patients. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:219-229. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Etienne-Grimaldi MC, Milano G, Maindrault-Goebel F, Chibaudel B, Formento JL, Francoual M, Lledo G, André T, Mabro M, Mineur L. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene polymorphisms and FOLFOX response in colorectal cancer patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69:58-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Watanabe T, Wu TT, Catalano PJ, Ueki T, Satriano R, Haller DG, Benson AB 3rd, Hamilton SR. Molecular predictors of survival after adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1196-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 648] [Cited by in RCA: 639] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Etienne MC, Chazal M, Laurent-Puig P, Magné N, Rosty C, Formento JL, Francoual M, Formento P, Renée N, Chamorey E. Prognostic value of tumoral thymidylate synthase and p53 in metastatic colorectal cancer patients receiving fluorouracil-based chemotherapy: phenotypic and genotypic analyses. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2832-2843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Kawakami K, Ishida Y, Danenberg KD, Omura K, Watanabe G, Danenberg PV. Functional polymorphism of the thymidylate synthase gene in colorectal cancer accompanied by frequent loss of heterozygosity. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2002;93:1221-1229. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Maus MK, Hanna DL, Stephens CL, Astrow SH, Yang D, Grimminger PP, Loupakis F, Hsiang JH, Zeger G, Wakatsuki T. Distinct gene expression profiles of proximal and distal colorectal cancer: implications for cytotoxic and targeted therapy. Pharmacogenomics J. 2015;15:354-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Strickler JH, Hurwitz HI. Bevacizumab-based therapies in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2012;17:513-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Pander J, Wessels JA, Gelderblom H, van der Straaten T, Punt CJ, Guchelaar HJ. Pharmacogenetic interaction analysis for the efficacy of systemic treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1147-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Watanabe T, Kobunai T, Yamamoto Y, Matsuda K, Ishihara S, Nozawa K, Iinuma H, Ikeuchi H. Gene expression of vascular endothelial growth factor A, thymidylate synthase, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 in prediction of response to bevacizumab treatment in colorectal cancer patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1026-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Aschele C, Debernardis D, Tunesi G, Maley F, Sobrero A. Thymidylate synthase protein expression in primary colorectal cancer compared with the corresponding distant metastases and relationship with the clinical response to 5-fluorouracil. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4797-4802. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Marsh S, McKay JA, Curran S, Murray GI, Cassidy J, McLeod HL. Primary colorectal tumour is not an accurate predictor of thymidylate synthase in lymph node metastasis. Oncol Rep. 2002;9:231-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Liu Q, Yu Z, Xiang Y, Wu N, Wu L, Xu B, Wang L, Yang P, Li Y, Bai L. Prognostic and predictive significance of thymidylate synthase protein expression in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Biomark. 2015;15:65-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Chu E, Voeller DM, Jones KL, Takechi T, Maley GF, Maley F, Segal S, Allegra CJ. Identification of a thymidylate synthase ribonucleoprotein complex in human colon cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:207-213. [PubMed] |