Published online Aug 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i30.5589

Peer-review started: October 19, 2016

First decision: December 2, 2016

Revised: May 12, 2017

Accepted: June 18, 2017

Article in press: June 19, 2017

Published online: August 14, 2017

Processing time: 303 Days and 9.5 Hours

To assess the efficacy and safety of a Chinese herbal medicine (CHM), Xiangsha Liujunzi granules, in the treatment of patients with functional dyspepsia (FD).

We performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with patients from three centers. Two hundred and sixteen subjects diagnosed with FD according to ROME III criteria and confirmed by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and spleen-deficiency and Qi-stagnation syndrome were selected to receive Xiangsha Liujunzi granules or placebo for 4 wk in a 2:1 ratio by blocked randomization. The subjects also received follow-up after the 4-wk intervention. Herbal or placebo granules were dissolved in 300 mL of water. Participants in both groups were administered 130 mL (45 °C) three times a day. Participants were evaluated prior to and following 4 wk of the intervention in terms of changes in the postprandial discomfort severity scale (PDSS) score, clinical global impression (CGI) scale score, hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) score, traditional Chinese medicine symptoms score (SS), scores of various domains of the 36-item short form health survey (SF-36), gastric emptying (GE) and any observed adverse effects.

Compared with the placebo group, patients in the CHM group showed significant improvements in the scores of PDSS, HADS, SS, SF-36 and CGI scale (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01). They also showed the amelioration in the GE rates of the proximal stomach and distal stomach (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01).

Xiangsha Liujunzi granules offered significant symptomatic improvement in patients with FD.

Core tip: Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a common clinical functional gastrointestinal disease with a very high incidence, seriously affecting the quality of life of patients. However, current chemical drugs do not achieve good curative effects. In the present study we performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy and safety of a Chinese herbal medicine, Xiangsha Liujunzi granules, in the treatment of patients with FD. We found that Xiangsha Liujunzi granules offered significant symptomatic improvement in patients with FD without adverse effects.

- Citation: Lv L, Wang FY, Ma XX, Li ZH, Huang SP, Shi ZH, Ji HJ, Bian LQ, Zhang BH, Chen T, Yin XL, Tang XD. Efficacy and safety of Xiangsha Liujunzi granules for functional dyspepsia: A multi-center randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical study. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(30): 5589-5601

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i30/5589.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i30.5589

Functional dyspepsia (FD), one of the most frequently encountered disorders of the gastrointestinal tract, is defined as the presence of symptoms originated in the epigastrium in the absence of any systemic, organic, or metabolic disease that is likely to explain the symptoms and is characterized by symptoms of meal-induced postprandial fullness or early satiety and upper abdominal discomfort or pain[1,2]. Previous studies have reported that the prevalence of FD varies considerably among different population-based studies, with percentages ranging from to 11% to 29%[3]. FD has symptoms similar to those of other conditions, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), peptic ulcer disease and gastroesophageal reflux. The two diagnostic categories of FD are (1) postprandial distress syndrome (PDS), which is characterized by the presence of meal-related early satiety and fullness; and (2) epigastric pain syndrome (EPS), which is characterized by the prominent symptom of epigastric pain that is generally not meal-related. However, evidence of their degree of overlap is mixed. Although its pathogenesis has not yet been fully clarified, abnormalities in gastric motor and sensory function and, more recently, low-grade duodenal inflammation have been identified[4,5]. The major pathophysiological mechanism underlying symptoms of FD is disorders of gastrointestinal motility[6]. Motility disorders lead to impaired gastric accommodation, myoelectric activity abnormalities and delayed gastric emptying (GE). Therefore, a prokinetic treatment approach is preferred in PDS. Recent evidence suggests that the subtypes of FD correlated with unhealthy dietary behaviors, especially skipping meals, eating extra meals and a preference to gas-producing food and sweet food[7]. It was recently found that the nutritional habits of FD patients are also a major factor in the production of discomfort symptoms. Carbonated drinks and fatty and spicy foods were the most common triggering food items in FD patients. Carbonated drinks and legumes were more likely to cause a symptom in PDS[8]. As the exact pathogenesis of FD has not yet been fully clarified, therapeutic drugs to relieve symptoms have thus not yet been established.

Symptomatic management of FD depends on the predominant symptoms and remains a substantial challenge. Treatment can include dietary modifications, antiemetics, antispasmodics, prokinetics, antidepressants and analgesics, as well as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)[9-12]. Despite the emergence of acotiamide in Japan[13], which has given hope to some FD patients, it does not benefit more patients. Therefore, the limited effectiveness of chemical drugs and the side effects of synthetic drugs make assessments of herbal preparations an appealing prospect[14]. It is becoming increasingly difficult to ignore the role of complementary and alternative medicine in the treatment of FD. Approaches based on complementary and alternative medicine in the treatment of FD have a long history, and several modalities have been investigated with some promising results[15]. A considerable amount of literature reported that at least 44 different herbal products have been recommended alone or in combination for the treatment of dyspeptic symptoms[16]. Complementary and alternative medicine consists of traditional Persian medicine (TPM), traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and so on. Jollab, a TPM, appeared to be more effective than the placebo in patients with FD[17]. Adjuvant supplementation of honey-based formulation of Nigella sativa and the association between ginger and artichoke leaf extracts can cause significant symptomatic improvement in patients with FD[18,19]. Since Liujunzi decoction was proved to be effective against FD by a randomized controlled trial for the first time, a considerable amount of literature has been published on the treatment of FD with Chinese herbal medicine (CHM)[20,21]. To date, as the good efficacy of CHM for the relief of symptoms of FD, many dyspeptic patients chose CHM. Clinically, CHM is used in combination with Western medications or alone in China. The essence of TCM is treatment based on syndrome differentiation, which is based on the different conditions of each patient. At present, the phenomenon of the same drug treatment for the same disease with the same medicine is applied. Based on TCM theory, PDS can be categorized as “stuffiness and fullness”, and the most related organ is the “spleen”. A previous study has already demonstrated that the syndrome of “spleen-deficiency and Qi-stagnation” was the most common syndrome type in FD patients[22]. Based on these findings, the herbal preparation Xiangsha Liujunzi granules, a classical TCM formula, was designed and utilized in treating FD patients with “spleen-deficiency and Qi-stagnation” syndrome.

Despite ongoing clinical use, uncertainty remains regarding clinical efficacy and safety of CHM in the treatment of FD. The aim of this multicenter, double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial was to assess whether 4 wk of therapy with CHM was more efficacious than placebo in the relief of FD dyspeptic symptom and in improving quality of life[23]. We hoped to find strong evidence to support the use of CHM in PDS patients.

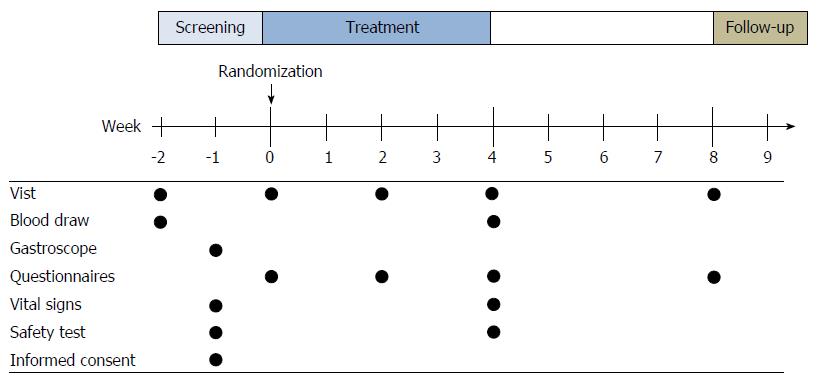

This study is a multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial with two arms to examine the safety and efficacy of Xiangsha Liujunzi granules in the treatment of PDS patients. Participants were randomized into Xiangsha Liujunzi decoction or placebo groups in a 2:1 ratio. Since assigning an equal number of ill subjects to the ineffective placebo treatment was unethical, the 2:1 randomization plan was chosen to protect the rights of the subjects. The protocol was developed according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement[24] , Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) 2013[25] and SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials[26]. The CHM group received Xiangsha Liujunzi granules, and the placebo group received a placebo. Then, all participants underwent a 4-wk treatment, followed by a 4-wk follow-up period. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees of Xiyuan Hospital of China Academy of Chinese medical sciences, Wuhan Integrated TCM and Western Medicine Hospital, and Guangdong Province TCM Hospital, and informed consent was obtained from each participant. The study design is shown in Figure 1.

Subjects were recruited from outpatients of three hospitals (Xiyuan Hospital of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Guangdong Province Traditional Chinese Medical Hospital, Wuhan Integrated TCM & Western Medicine Hospital) in China, between July 2013 and July 2016. Participants were recruited through advertising media, direct calls, and health promotion events. Advertisements were put on notice boards and homepages of the hospitals and local newspapers. Patients were required to provide their medical history, receive a physical examination and laboratory safety tests, and undergo a gastroscopy. Only those who fulfilled the Rome III criteria (Table 1) and TCM Diagnostic Criteria for Distention and Fullness (Table 2) of the principle for clinical research on new drugs of TCM[27] were considered eligible subjects. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 3. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to inclusion in the trial. Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

| Functional dyspepsia | Subtype |

| The last 3 mo with symptom onset at least 6 mo before diagnosis, and must include: | Postprandial distress syndrome |

| 1 One or more of: | Must include one or both of the following: |

| a, Bothersome postprandial fullness | 1 Bothersome postprandial fullness, occurring after ordinary sized meals, at least several times per week |

| b, Early satiation | 2 Early satiation that prevents finishing a regular meal, at least several times per week |

| c, Epigastric pain | Supportive criteria |

| d, Epigastric burning | 1 Upper abdominal bloating or postprandial nausea or excessive belching can be present |

| AND | 2 EPS may coexist |

| 2 No evidence of structural disease (including at upper endoscopy) that is likely to explain the symptoms | |

| Spleen-deficiency and Qi-stagnation | |

| Primary symptoms | Abdominal distension, with obviously postprandial distress |

| Anorexia or little appetite | |

| Secondary symptoms | Nausea; acid reflux/heartburn; loose stools; fatigue/exhausted |

| Fat tongue with slightly white coating | |

| Weak pulse |

| Inclusion criteria |

| 1 Age 18-70 yr, Chinese reading and writing ability |

| 2 Meeting the Rome III diagnostic criteria for PDS |

| 3 Having the symptom of “spleen-deficiency and Qi-stagnation”, “spleen-deficiency and damp-obstruction”, “spleen-Yang deficiency”. |

| 4 Signing the informed consent form |

| Exclusion criteria |

| 1 Combined with GI ulcer, erosive gastritis, atrophic gastritis, severe dysplasia of gastric mucosa or suspicious malignant lesion |

| 2 Having overlap syndrome combined with gastroesophageal reflux disease or irritable bowel syndrome |

| 3 Having alarm symptoms (weight loss, black or tar stool, dysphagia, etc.) |

| 4 Having serious structural disease (disease of heart, lung, liver or kidney) or mental illness |

| 5 History of surgery related with the gastrointestinal tract, except for appendectomy more than six months ago |

| 6 Taking drugs which may affect the gastrointestinal tract, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin |

| 7 Allergy to the experimental medication |

| 8 Difficulties in attending the trial (paralysis, serious mental illness, dementia, renal diseases, stroke, coronary atherosclerotic heart diseases, diabetes or mental diseases, illiteracy, etc.) |

| 9 Pregnant or breastfeeding |

| 10 Refusing to sign the informed consent form |

The participants in the three hospitals were randomly assigned to two groups using block randomization. Random numbers based on the allocation sequence were generated using SAS (Version 9.2, Channel-leadian Pharmaceuticals R&D, Co., Ltd.; Haidian District, Beijing) by an independent statistician at the Good Clinical Practice (GCP) center of Xiyuan Hospital. Each randomization number was placed in a sequentially numbered opaque envelope that was sealed by the clinical research coordinator. After screening, the clinical investigator assigned the treatment according to the randomization number. Participants, clinical investigators, statisticians, and all related study staff were blinded. The blinding procedure was also verified by the authorized contract research organization. Group assignments were not revealed until the entire study was completed except in emergency situations if practical intervention was compulsory for further management of the participant.

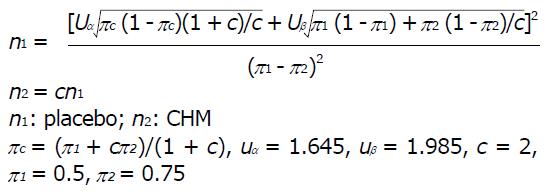

The trial was powered for superiority testing for the primary point. According to our preliminary studies, the effective rate of the Xiangsha Liujunzi decoction in treating FD was between 67% and 80%, and we estimated that the average effective rate was 70%, whereas that of the placebo for FD was approximately 45%[28]. A one-sided test yielding a 2.5% significance level was used to prove the hypothesis that Xiangsha Liujunzi granules is more effective than placebo for treating PDS. The patients were assigned to either the CHM group or the placebo group in a 2:1 ratio. The sample size was based on the superiority design as follows:

Math 1

The calculation indicated that a sample size of 180 would be sufficient (n = 120 in the CHM group, n = 60 in the control group). To allow for a 20% rate of dropouts and missing data, we recruited 144 patients for the CHM group and 72 patients for the placebo group.

Qualified patients received a unique treatment number, which was fixed throughout the duration of the trial. The medication allocation was based on the treatment number. The composition and action of the herbal preparation of Xiangsha Liujunzi granules are summarized in Table 4. The placebo granules were made from dextrin (80%), rice (15%), bitter principle (5%) and coloring matter to ensure that the color, smell, taste and texture were similar to those of Xiangsha Liujunzi granules. Patients were informed to dissolve a sachet of granules (14 g) in 130 mL of hot water and to take the solution orally three times daily 1 h after breakfast, lunch and dinner for 4 wk. Both the herbal formula and placebo granules were manufactured by Beijing Tcmages Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Shunyi District, Beijing) according to the standards of good manufacturing practice. All medications were packed identically in opaque aluminum bags with the same labeling form except the treatment number.

| Scientific name | Part used | Proportion of ingredients (100%) |

| Astragalus mongholicus | Root | 12 |

| Codonopsis pilosula | Root | 12 |

| Rhizoma Atractylodis Macrocephalae | Rhizome | 12 |

| Poria cocos | Sclerotium | 12 |

| Fructus Aurantii | Fruit | 12 |

| Amomum villosum | Fruit | 6.4 |

| Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort | Sclerotium | 9.6 |

| Rhizoma corydalis | Rhizoma | 9.6 |

| Medicated Leaven | Fermentation products | 12 |

| Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch | Root | 2.4 |

This trial was conducted according to the standards of the International Committee on Harmonization on GCP and the revised version of the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional review boards at Xiyuan Hospital of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Wuhan Integrated TCM & Western Medicine Hospital, and Guangdong Province TCM Hospital approved this protocol. This trial was registered in the ChiCTR (ChiCTR-TRC-13003200, 19 April 2013) and Clinical Trials.gov (NCT02762136).

Primary outcome: We assessed FD symptoms using the change in postprandial discomfort severity scale (PDSS) from baseline (week 0) to the treatment endpoint (week 8).

PDSS: Based on Rome III criteria and past clinical trials[29], PDSS was designed to evaluate dyspeptic symptoms, including postprandial fullness, early satiety, upper abdominal pain or discomfort, and heartburn. The severity and frequency of each symptom are separately evaluated by a defined numerical score. The severity was scored as follows: 0, absent; 1, mild (awareness of symptoms but easily tolerated); 2, moderate (interference with normal activities); and 3, severe (incapacitating). The total severity score ranged from 0 to 12. The frequency scoring used the following scale: 0, absent (less than once per month); 1, rarely (less than once per week); 2, occasionally (less than three times per week); and 3, often (more than or three times per week). The total frequency score ranged from 0 to 12.

Changes in the clinical global impression (CGI) scale score, TCM symptom score (SS), MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) score, hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) score, and GE were considered secondary outcomes.

CGI scale: The CGI scale[30] comprises two parts: CGI-severity (CGI-S) and CGI-improvement (CGI-I). The former evaluates the severity of psychopathology from 1 to 7, and the latter assesses the change from the initiation of treatment on a similar seven-point scale. In CGI-S, clinical investigators need to answer one question: “Considering your total clinical experience with this particular population, how mentally ill is the patient at this time?”, which is rated on the seven-point scale: 1 = normal, not at all ill while 7 = the most extremely ill. Similarly, in CGI-I, clinical investigators need to answer another question: “Compared to the patient’s condition at admission to the project, how is this patient’s condition?” which is also rated on a seven-point scale: 1 = very much improved since the initiation of treatment; 4 = no change from baseline; 7 = very much worse since the initiation of treatment.

TCM SS: TCM SS is a scale utilized to evaluate the participant’s discomfort of PDS based on TCM theory. SS contains 15 items of TCM terminology, which are used to assess the presence (yes/no) and severity of physical discomfort (0 = absent; 1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 = severe).

SF-36: SF-36, the most commonly used tool to assess quality of life that contains 36 items in eight dimensions, was used to assess the effect of experimental medication. The eight dimensions consist of general health (GH), physical functioning (PF), role physical (RP), role emotional (RE), social functioning (SF), bodily pain (BP), vitality (VT) and mental health (MH)[31].

HADS: The HADS, first developed by Snaith and Zigmond in 1983, was usually used to identify cases (possible and probable) of anxiety disorders and depression among patients in non-psychiatric hospitals[32-34]. The scale consists of 14 items, 7 related to anxiety (HADS-A) and 7 related to depression (HADS-D), each scored between 0 and 3. The authors of this scale recommended that if an individual had a score of 8, he/she should be regarded as a possible case. It was found that this threshold was optimal for HADS-A and HADS-D in both the general population and patients with somatic symptoms.

GE: GE was observed using gastric ultrasound[35]. Participants were asked to fast overnight before the ultrasonography. A 1120 mL esculent liquid was used as the test meal and was prepared by mixing 50 g of nutrient Cola Cao (enteral nutritional solid beverage, chocolate; Tianjin Cola Cao Food Co., LTD, Tanjin, China) and 100 g of milk powder (Nestle whole milk powder; Shuangcheng Nestle Co., Ltd, Heilongjiang, China) with 1100 mL of warm water, and the entire test meal volume was 1120 mL. This esculent liquid contained 26.5 g of protein, 29.1 g of fat and 75.5 g of carbohydrate (840 kcal). This mixed liquid meal consisted of 13% proteins, 48% carbohydrates and 39% lipids and was used at a caloric density of 0.75 kcal/mL. The liquid test meal was administered orally as tolerated at a fixed rate of 50 mL/min, and all participants were allowed to sit stationary on a chair for approximately 5 min while drinking this test meal. The subjects were scanned in a half-sitting position, sitting on an examining chair and leaning back at an angle of approximately 120°. Subjects were instructed not to move and to hold their breath at the end of expiration to permit diaphragmatic rising and restoration of the gastric configuration (Figure 2).

The proximal stomach and distal stomach volumes of each subject were scanned at six time points, which were fasting, maximum satiety, and 30 min, 60 min, 90 min, and 120 min after beginning ingestion.

GE rate was calculated as follows: (Amax - A)/Amax × 100 (%), where Amax is the volume of maximum satiety after the meal in the proximal stomach or distal stomach, and A is the volume at other time points after the meal in the proximal stomach or distal stomach.

To assess the safety of the 4 wk treatment, routine tests of blood, urine and stool samples, as well as an electrocardiogram and blood biochemical tests (ALT, AST, BUN, Scr) were conducted before randomization and immediately after the completed treatment. During the trial, any adverse events were recorded in detail and documented using case report forms, and appropriate treatment was provided to the participant immediately if necessary.

All statistical analyses were conducted in a blind manner by an independent statistician using SPSS (Version 19.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States). Significance was defined as a 2-sided P value of < 0.05. Demographic, clinical, and outcome variables were described using mean ± SD for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. First, the baseline characteristics of both groups were compared, including gender, age, and level of education. Second, the efficacy of CHM and placebo was compared, including the primary outcome and all secondary outcomes. All analyses in this study were based on the intention-to-treat principle. Missing values were recorded by the last-observation-carried-forward method, and this analysis imputes the last measured value of the endpoint to all subsequent scheduled but missing evaluations. The baseline characteristics were compared using either χ2 or the Student’s t-tests. Primary and secondary outcomes are presented as the mean and SD and were analyzed using independent t-tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Adverse events were calculated and compared using χ2 test.

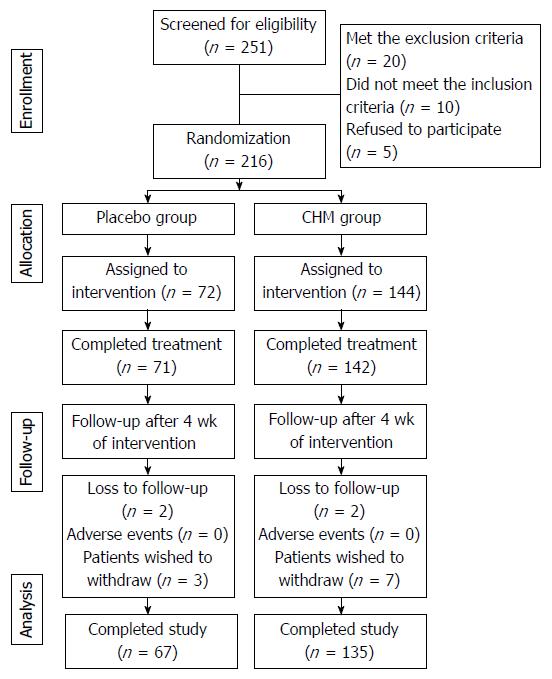

Between July 2013 and July 2016, a total of 216 patients were recruited: 144 were randomized into the CHM group, and 72 were randomized into the placebo group. Fourteen patients withdrew from the trial due to a lack of efficacy (9 patients in the CHM group and 5 patients in the placebo group). No adverse events were reported. The physiological tests obtained after 4 wk of treatment showed no abnormal values.

The flow of participants in the study is summarized in Figure 3.

The general characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 5. No significant differences were identified between the two groups in parameters such as gender, age and level of education.

| Characteristic | Placebo group (n = 67) | CHM group (n = 135) | |

| Gender | Female | 86 (63.7) | 43 (64.2) |

| Age | mean ± SD | 43.89 ± 13.32 | 44.33 ± 12.41 |

| 20-29 | 12 (17.9) | 21 (15.6) | |

| 30-39 | 18 (26.9) | 28 (20.7) | |

| 40-49 | 8 (11.9) | 31 (22.9) | |

| 50-59 | 17 (25.4) | 28 (20.7) | |

| 60+ | 12 (17.9) | 21 (15.6) | |

| Level of education | Primary school | 5 (7.5) | 9 (6.7) |

| Junior school | 6 (8.9) | 22 (16.3) | |

| Senior school | 15 (22.4) | 23 (17) | |

| Degree or above | 41 (61.2) | 81 (60) | |

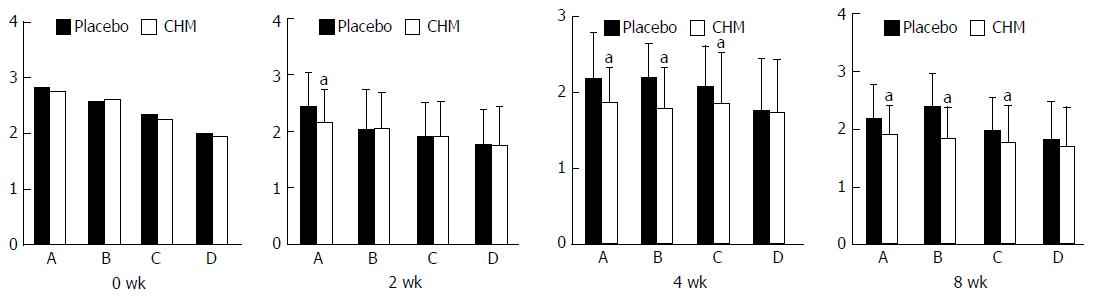

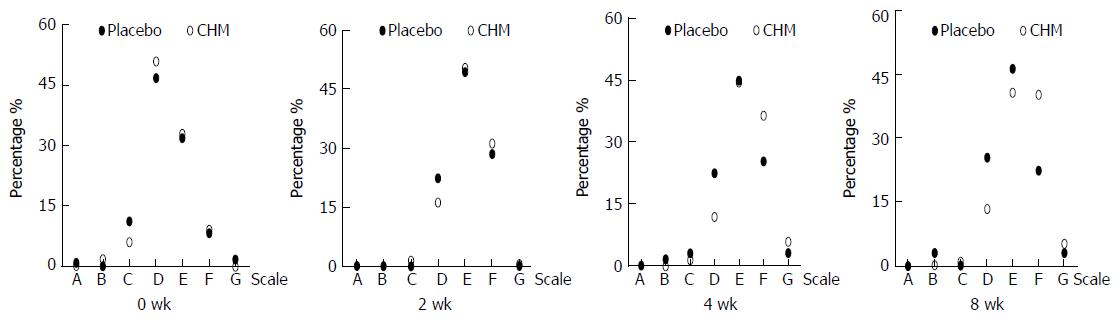

PDSS: At week 2, the symptom score of postprandial fullness in the CHM group was significantly better than that in the placebo group (t = 3.561, P = 0.000). After 4 wk of treatment, the scores of postprandial fullness, early satiety and epigastric pain of PDSS assessed by patients were significantly better in the CHM group than in the placebo group (t = 3.976, P = 0.000; t = 5.302, P = 0.000; t = 2.077, P = 0.039). These three symptom scores were also significantly better in the CHM group than in the placebo group during the follow-up period (t = 3.336, P = 0.001; t = 6.658, P = 0.000; t = 2.244, P = 0.026). The results were clinically meaningful (Figure 4).

CGI scale: After 4 wk of treatment, the ratings of the CGI showed the following significant results for the CHM group vs placebo group: very much improved (5.9% vs 3.0%), much improved (36.3% vs 25.4%), slightly improved (44.4% vs 44.8%), and unchanged or deteriorated (11.8% vs 22.4%) (Z = -2.244, P = 0.025). The ratings of the CGI between the CHM group and placebo group during the follow-up period were as follows: very much improved (5.2% vs 3.0%), much improved (40.0% vs 22.4%), slightly improved (40.7% vs 46.3%), and unchanged or deteriorated (13.3% vs 25.4%) (Z = -2.054, P = 0.04). The results were clinically meaningful (Figure 5).

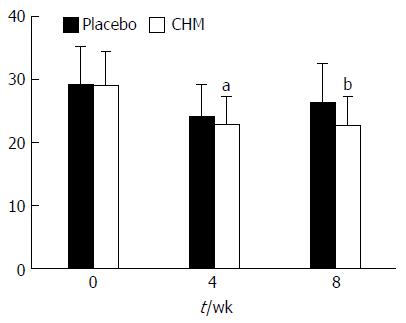

TCM SS: There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding SS at baseline (t = -0.173, P = 0.863). After 4 wk of treatment, SS in the CHM group was significantly better than that in the placebo group (t = -2.067, P = 0.04). The same result was also found during the follow-up period (t = -4.752, P = 0.000) (Figure 6).

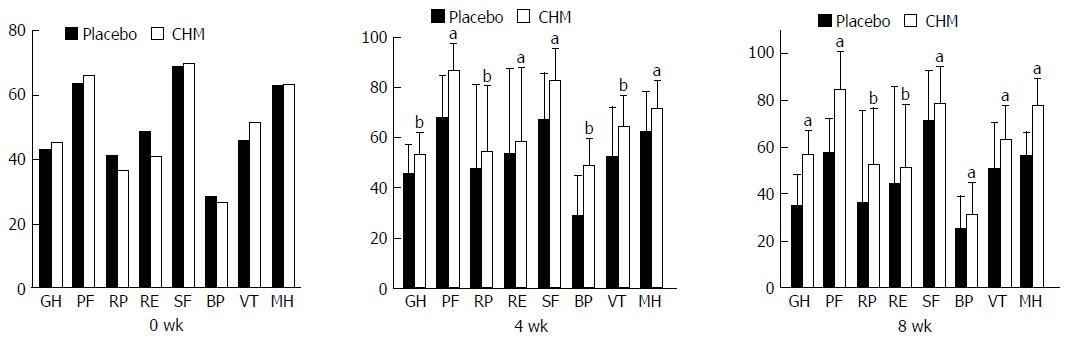

SF-36: There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding the eight dimensions of GH, PF, RP, RE, SF, BP, VT and MH in the SF-36 at baseline (t = -1.33, P = 0.185; t = -1.44, P = 0.151; t = 0.787, P = 0.432; t = 1.248, P = 0.214; t = 0.267, P = 0.79; t = 0.631, P = 0.529; t = -1.965, P = 0.051; t = -0.372, P = 0.71). After 4 wk of treatment, the SF-36 scores in the CHM group were significantly better than those in the placebo group (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01). The same result was also found during the follow-up period (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01) (Figure 7).

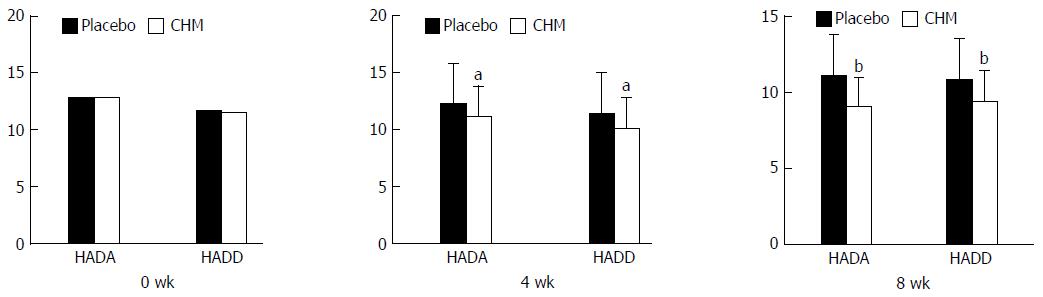

HADS: There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding HADA and HADD (t = 0.016, P = 0.987; t =-0.400, P = 0.690) at 0 wk. After 4 wk of treatment, the HADA and HADD scores in the CHM group were significantly better than those in the placebo group (t = -2.179, P = 0.032; t = -2.429, P = 0.017). The same result was also found during the follow-up period (t = -2.76, P = 0.006; t = -3.646, P = 0.000) (Figure 8).

GE: The GE rate of the proximal stomach (GERPG) in the CHM group at various time points was higher than that of the control group, and the differences were significant (P < 0.01). Moreover, the gastric emptying rate of the distal stomach (GERDG) in the CHM group, compared with the control group, decreased at 30 min after the meal but increased at the other time points, and the differences were significant (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01) (Table 6).

| Time | Placebo (n = 67) | CHM (n = 135) | t | P value |

| 0 wk | ||||

| GE rate of proximal stomach | ||||

| 30 min | 32.85 ± 19.27 | 30.91 ± 16.67 | 0.653 | 0.515 |

| 60 min | 49.26 ± 18.67 | 49.46 ± 17.74 | -0.066 | 0.947 |

| 90 min | 66.37 ± 14.63 | 63.72 ± 17.51 | 0.948 | 0.344 |

| 120 min | 76.54 ± 13.97 | 75.39 ± 13.91 | 0.487 | 0.627 |

| GE rate of distal stomach | ||||

| 30 min | 15.68 ± 35.26 | 6.81 ± 37.61 | 1.576 | 0.117 |

| 60 min | 32.49 ± 30.82 | 26.91 ± 33.36 | 1.124 | 0.263 |

| 90 min | 49.26 ± 25.93 | 41.84 ± 33.59 | 1.555 | 0.122 |

| 120 min | 61.61 ± 21.85 | 57.52 ± 27.02 | 1.053 | 0.294 |

| 4 wk | ||||

| GE rate of proximal stomach | ||||

| 30 min | 28.48 ± 13.13 | 36.31 ± 10.78 | -4.195 | 0.000 |

| 60 min | 47.21 ± 16.76 | 56.92 ± 10.27 | -4.722 | 0.000 |

| 90 min | 59.59 ± 17.71 | 72.92 ± 16.94 | -6.919 | 0.000 |

| 120 min | 71.47 ± 16.94 | 82.31 ± 7.35 | -5.888 | 0.000 |

| GE rate of distal stomach | ||||

| 30 min | 7.03 ± 35.40 | -24.34 ± 34.02 | 5.707 | 0.000 |

| 60 min | 26.94 ± 31.39 | 40.83 ± 16.37 | -3.871 | 0.000 |

| 90 min | 50.06 ± 21.97 | 56.90 ± 15.35 | -2.406 | 0.017 |

| 120 min | 61.89 ± 15.26 | 67.66 ± 13.41 | -2.578 | 0.011 |

Adverse effects: In the 4 wk treatment and the follow-up period, all subjects had no adverse effects.

FD is a common gastrointestinal disease. The prevalence of FD is 20%-25% in Western countries and 8%-23% in Asia[36,37]. In China, approximately 10% of general outpatients have dyspepsia, which account for 50% of digestive internal medicine clinic services. FD involves various pathophysiological disturbances and many pathogenic factors, including impaired accommodation, delayed GE, and hypersensitivity to gastric distention. Several studies have reported that visceral hypersensitivity is the mechanism of postprandial abdominal bloating and distension. The normal abdominal accommodation is altered by an abnormal viscerosomatic response to meal ingestion[38]. Patients with PDS have the characteristics of fasting and postprandial hypersensitivity, while patients with EPS have the characteristics of a reduction in gastric compliance[39]. There are multiple drug options in clinical practice, including PPIs, prokinetic agents, anti-Helicobacter pylori drugs, antidepressant drugs and mucosal protective agents. Because the pathophysiology of FD involves several physiological systems and a variety of treatment classes are available, health care providers face uncertainty in selecting therapies for patients with FD. Furthermore, these chemical drugs are not satisfactory or effective. Therefore, many patients with FD seek treatment with complementary and alternative medicine[15]. TCM, as an important component of complementary and alternative medicine, has attracted increasing attention in the world, especially in the treatment of functional gastrointestinal diseases.

Based on TCM theory, the “spleen” governs movement and transformation of food and fluid. Emotional injury, food or drink, and congenital defects are main pathogenic factors of a functional disorder of the “spleen”, which can lead to the stagnation of Qi and dampness and then result in “stuffiness and fullness”. As spleen deficiency is the essence of these three types of syndrome, invigorating the spleen is the critical principle of treatment[40,41]. This pathogenic factor causes abnormal function of the upper abdomen, spleen and stomach, resulting in the presence of abdominal distension, appetite disorder, loose stools, and lassitude. The TCM pathogenesis of FD is spleen deficiency and Qi-stagnation. Xiangsha Liujunzi decoction is a classical formula based on invigorating the spleen and has been used by TCM doctors for hundreds of years. In the past two decades, a considerable number of clinical trials have proved the efficacy and safety of this decoction in the treatment of FD[20,34,42,43]. Currently, no patient-reported outcome instrument is available for the evaluation of treatment efficacy in PDS, which makes the evaluation of treatment effects in FD difficult. To improve the evaluation criteria of this study, we chose the PDSS, CGI, SS, SF-36, and HADS. CGI instrument, an established outcome measure in psychopharmacology research, is a reliable measure of fatigue[44]. Symptoms of fatigue are often part of the clinical presentation of spleen deficiency. Mental and psychological disorders are one of the pathogenic factors for FD. Clinically, we found many FD patients with anxiety and depression symptoms. One of the “gold standard” to assess the efficacy of antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications is the Hamilton rating scale. Another scale to assess the efficacy of antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications is the CGI, which has similar effect sizes to the HAM rating scale[45]. Therefore, CGI instrument has been used in clinical practice as well as research. Zigmond and Snaith devised the HADS, which has the advantages of simplicity, fastness and ease of use, to assess anxiety and depression in a general medical population 33 years ago[46]. This scale has recently been used to assess FD patients with anxiety and depression. The remarkable placebo response is the most difficulty in clinical trials on FD patients. In order to ensure that the participants could not be able to make a distinction between placebo and active treatment, we tried our best to make the drugs in the two groups indistinguishable for the participants. The placebo granules were made from 80% dextrin, 15% rice, 5% bitter principle and coloring matter to ensure that the color, smell, taste and texture were similar to those of Xiangsha Liujunzi granules. In this clinical study, we found that Xiangsha Liujunzi granules can relieve the postprandial fullness, early satiety, and epigastric pain symptoms in PDS patients, but the improvement in the epigastric burning sensation was not superior to that achieved by the placebo. This result may be because the inhibition of gastric acid secretion by CHM was not better than that of PPIs. The SF-36 scale was used to evaluate the improvement in quality life of patients. Our results showed the advantage of the CHM compared to placebo, with a significant improvement of 8 subscale scores of GH, PF, RP, RE, SF, BP, VT, MH on the SF-36 at 2 wk and 4 wk. These results persisted until the end of the study (8 wk). The pathophysiology of FD is diverse and its symptoms are non-specific; the pathogenesis of FD is also related to mental and psychological factors. Therefore, some antidepressants have been used to treat FD, such as mirtazapine[47]. According to our results, the HADA and HADD scores were both reduced in the CHM group compared to the placebo group at 4 wk and 8 wk, and there was a significant difference between the two groups. The CHM treatment had significant improvement in gastrointestinal-specific anxiety and depression. This study also showed that TCM symptom scores significantly improved from 2 wk to 4 wk with CHM treatment, and the result persisted to the follow-up time (8 wk). This finding shows that TCM treatment can reduce the recurrence of FD symptoms. Finally, after 4 wk of CHM treatment, the number of participants with very much improved and much improved scores on the CGI scale, compared to placebo, was significantly higher at 4 wk.

FD is one of the most common gastrointestinal diseases, accounting for up to 5% of outpatients in gastroenterology department[48]. GE of patients with FD is usually delayed in 30%-50%[49], including both liquid emptying[50] and solid emptying[48]. Food ingestion can directly aggravate dyspeptic symptoms of patients with FD. Data from questionnaires revealed that 75% of patients with FD had experience of aggravation of dyspeptic symptoms after ingestion of a meal. Previous studies had reported that 90% of patients with FD had aggravation of dyspeptic symptoms after ingestion of a standardized 250-kcal meal, and maximum symptom severity occurred between 45 and 90 min after meal[51]. In this study, we calculated the GERPG and GERDG at 4 time points and found that the GERDG of the CHM group at 30 min after a meal was negative. As we know, the proximal stomach functions as a reservoir, and the liquid food flows into the distal stomach and enlarges the volume of the distal stomach over time. This factor caused an illusion that the GERDG of the CHM group was decreased. Compared with those of the placebo group, the GERPG and GERDG of the CHM group were increased at 60 min, 90 min, and 120 min after the meal. The results of this study suggest that the curative effect of Xiangsha Liujunzi decoction can promote GE of patients with PDS. Furthermore, throughout the course of the experiment, participants were not found to have any adverse events.

We have demonstrated the clinical efficacy of the Xiangsha Liujunzi granules to improve the symptomatic symptoms of patients with FD. In this randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial, Xiangsha Liujunzi granules was shown to be effective in the management of FD, especially in patients with postprandial fullness and bloating, early satiety, and epigastric pain. This treatment will provide a new option for clinicians in treating PDS. However, the mechanism of action for CHM to reduce gastrointestinal symptoms is still unknown, and further studies are needed to determine the precise mechanisms of action.

Functional dyspepsia (FD), one of the most common functional gastrointestinal disorders, has two diagnostic categories that are postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) and epigastric pain syndrome. Its prevalence ranges from 11% to 29%, and it seriously affects the quality of life of patients. However, current chemical drugs do not achieve good curative effect, and it is therefore necessary to find a new therapy for FD.

The major pathophysiological mechanism of PDS is gastric motility disorder, therefore, searching for a kind of effective treatment for PDS is the current research hotspot. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has the advantage of treating PDS. Xiangsha Liujunzi decoction is a classical formula based on invigorating the spleen and has been used in clinical practice for hundreds of years. Gastric ultrasound is usually used to observe the gastric emptying (GE), but its value in assessing the promoting effect of Chinese herbal medicines (CHMs) on gastric motility has not yet been studied.

Although in the past two decades, a considerable number of clinical trials have proved the efficacy and safety of this decoction in the treatment of FD, there are still some disadvantages in assessing its efficacy. The authors use gastric ultrasound to observe proximal and distal GE rates. The advantages of the technique include being non-invasive, accurate, and reliable.

The authors provide strong evidence to support the use of CHM in PDS patients. This treatment will provide a new option for clinicians in treating PDS in the future.

TCM, an independent medical system well known in China, has four ways of diagnosis that are look, listen, question and feel the pulse. It takes Yin-Yang and five elements as the theoretical basis, which holds that the human body is regarded as the unity of Qi, form and spirit. The basic principle of understanding and treating diseases for TCM is syndrome differentiation. CHMs are natural medicines that consist of plant medicine (root, stem, leaf and fruit), animal medicine (viscera, skin, bone, organ, etc.) and mineral medicine. The use of CHMs is conducted under the guidance of the theory of TCM.

This paper describes a new method for treating PDS. The authors designed a multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial with two arms to examine the safety and efficacy of Xiangsha Liujunzi granules in the treatment of PDS patients. They assessed PDS symptoms using the change in PDSS, clinical global impression scale, TCM symptom scores, MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey, and hospital anxiety and depression scale. Further, they assessed proximal and distal GE rates by gastric ultrasound, which is non-invasive, accurate, and reliable. This clinical trial study provides strong evidence to support the use of CHM in PDS patients. This treatment will provide a new option for clinicians in treating PDS in the future.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kim BJ, Kobayashi T S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Camilleri M, Stanghellini V. Current management strategies and emerging treatments for functional dyspepsia. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:187-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tack J, Talley NJ. Functional dyspepsia--symptoms, definitions and validity of the Rome III criteria. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:134-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Petrarca L, Nenna R, Mastrogiorgio G, Florio M, Brighi M, Pontone S. Dyspepsia and celiac disease: Prevalence, diagnostic tools and therapy. World J Methodol. 2014;4:189-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kindt S, Tack J. Impaired gastric accommodation and its role in dyspepsia. Gut. 2006;55:1685-1691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Talley NJ, Walker MM, Aro P, Ronkainen J, Storskrubb T, Hindley LA, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Agréus L. Non-ulcer dyspepsia and duodenal eosinophilia: an adult endoscopic population-based case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1175-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sanger GJ, Alpers DH. Development of drugs for gastrointestinal motor disorders: translating science to clinical need. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:177-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jiang SM, Lei XG, Jia L, Xu M, Wang SB, Liu J, Song M. Unhealthy dietary behavior in refractory functional dyspepsia: a multicenter prospective investigation in China. J Dig Dis. 2014;15:654-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Göktaş Z, Köklü S, Dikmen D, Öztürk Ö, Yılmaz B, Asıl M, Korkmaz H, Tuna Y, Kekilli M, Karamanoğlu Aksoy E, Köklü H, Demir A, Köklü G, Arslan S. Nutritional habits in functional dyspepsia and its subgroups: a comparative study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:903-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | van Zanten SV, Armstrong D, Chiba N, Flook N, White RJ, Chakraborty B, Gasco A. Esomeprazole 40 mg once a day in patients with functional dyspepsia: the randomized, placebo-controlled “ENTER” trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2096-2106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vakil N, Laine L, Talley NJ, Zakko SF, Tack J, Chey WD, Kralstein J, Earnest DL, Ligozio G, Cohard-Radice M. Tegaserod treatment for dysmotility-like functional dyspepsia: results of two randomized, controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1906-1919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bouras EP, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, Burton DD, Heckman MG, Crook JE, Richelson E. Effects of amitriptyline on gastric sensorimotor function and postprandial symptoms in healthy individuals: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2043-2050. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Talley NJ, Locke GR, Herrick LM, Silvernail VM, Prather CM, Lacy BE, DiBaise JK, Howden CW, Brenner DM, Bouras EP. Functional Dyspepsia Treatment Trial (FDTT): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of antidepressants in functional dyspepsia, evaluating symptoms, psychopathology, pathophysiology and pharmacogenetics. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:523-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Altan E, Masaoka T, Farré R, Tack J. Acotiamide, a novel gastroprokinetic for the treatment of patients with functional dyspepsia: postprandial distress syndrome. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;6:533-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Saad RJ, Chey WD. Review article: current and emerging therapies for functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:475-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lacy BE, Talley NJ, Locke GR, Bouras EP, DiBaise JK, El-Serag HB, Abraham BP, Howden CW, Moayyedi P, Prather C. Review article: current treatment options and management of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Thompson Coon J, Ernst E. Systematic review: herbal medicinal products for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1689-1699. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Pasalar M, Choopani R, Mosaddegh M, Kamalinejad M, Mohagheghzadeh A, Fattahi MR, Ghanizadeh A, Bagheri Lankarani K. Efficacy and safety of jollab to treat functional dyspepsia: a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Explore (NY). 2015;11:199-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mohtashami R, Huseini HF, Heydari M, Amini M, Sadeqhi Z, Ghaznavi H, Mehrzadi S. Efficacy and safety of honey based formulation of Nigella sativa seed oil in functional dyspepsia: A double blind randomized controlled clinical trial. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;175:147-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Giacosa A, Guido D, Grassi M, Riva A, Morazzoni P, Bombardelli E, Perna S, Faliva MA, Rondanelli M. The Effect of Ginger (Zingiber officinalis) and Artichoke (Cynara cardunculus) Extract Supplementation on Functional Dyspepsia: A Randomised, Double-Blind, and Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:915087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang S, Zhao L, Wang H, Wang C, Huang S, Shen H, Wei W, Tao L, Zhou T. Efficacy of modified LiuJunZi decoction on functional dyspepsia of spleen-deficiency and qi-stagnation syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yang N, Jiang X, Qiu X, Hu Z, Wang L, Song M. Modified chaihu shugan powder for functional dyspepsia: meta-analysis for randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:791724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhang SS, Chen Z, Xu WJ, Wang HB. Study on distribution characteristic of syndrome of 565 cases of functional dyspepsia by twice differentiation of symptoms and signs based on the cold, heat, deficiency, excess. Zhonghua Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2008;23:833-835. |

| 23. | Wang FY, Zhong LLD, Kang N, Dai L, Lv L, Bian LQ, Chen T, Zhang BH, Bian ZX, Wang XG. Chinese herbal formula for postprandial distress syndrome: Study protocol of a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Integrat Med. 2016;1-7. |

| 24. | Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG; CONSORT Group. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Clin Oral Investig. 2003;7:2-7. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, Laupacis A, Gøtzsche PC, Krleža-Jerić K, Hróbjartsson A, Mann H, Dickersin K, Berlin JA. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:200-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3262] [Cited by in RCA: 4656] [Article Influence: 388.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, Laupacis A, Gøtzsche PC, Krle A-Jerić K, Hrobjartsson A, Mann H, Dickersin K, Berlin JA. SPIRIT 2013 Statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2015;38:506-514. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Zheng XY. Guiding principle of clinical research on new drugs of Chinese medicine in the treament of stuffiness and fullness. In Guiding principle of clinical research on new drugs of Chinese medicine (trial implementation). Edited by Yu XH. Bejing: Chinese Medical Science and Technology Press; 2002: 54-58. . |

| 28. | Holtmann G, Talley NJ, Liebregts T, Adam B, Parow C. A placebo-controlled trial of itopride in functional dyspepsia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:832-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mearin F, de Ribot X, Balboa A, Salas A, Varas MJ, Cucala M, Bartolomé R, Armengol JR, Malagelada JR. Does Helicobacter pylori infection increase gastric sensitivity in functional dyspepsia? Gut. 1995;37:47-51. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Busner J, Targum SD. The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4:28-37. [PubMed] |

| 31. | McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40-66. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety And Depression Scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1334] [Cited by in RCA: 1696] [Article Influence: 77.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kido T, Nakai Y, Kase Y, Sakakibara I, Nomura M, Takeda S, Aburada M. Effects of rikkunshi-to, a traditional Japanese medicine, on the delay of gastric emptying induced by N(G)-nitro-L-arginine. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;98:161-167. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Kusunoki H, Haruma K, Hata J, Kamada T, Ishii M, Yamashita N, Inoue K, Imamura H, Manabe N, Shiotani A. Efficacy of mosapride citrate in proximal gastric accommodation and gastrointestinal motility in healthy volunteers: a double-blind placebo-controlled ultrasonographic study. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1228-1234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Oustamanolakis P, Tack J. Dyspepsia: organic versus functional. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:175-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ghoshal UC, Singh R, Chang FY, Hou X, Wong BC, Kachintorn U; Functional Dyspepsia Consensus Team of the Asian Neurogastroenterology and Motility Association and the Asian Pacific Association of Gastroenterology. Epidemiology of uninvestigated and functional dyspepsia in Asia: facts and fiction. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:235-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Burri E, Barba E, Huaman JW, Cisternas D, Accarino A, Soldevilla A, Malagelada JR, Azpiroz F. Mechanisms of postprandial abdominal bloating and distension in functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2014;63:395-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Di Stefano M, Miceli E, Tana P, Mengoli C, Bergonzi M, Pagani E, Corazza GR. Fasting and postprandial gastric sensorimotor activity in functional dyspepsia: postprandial distress vs. epigastric pain syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1631-1639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 40. | Lv L, Huang SP, Tang XD, Wang FY, Wang J, Luo SJ, Kang N. Theoretical Discussion on Treating Functional Dyspepsia From Spleen. Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2014;55:383-385. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 41. | Du HG, Ming L, Chen SJ, Li CD. Xiaoyao pill for treatment of functional dyspepsia in perimenopausal women with depression. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16739-16744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Takeda H, Sadakane C, Hattori T, Katsurada T, Ohkawara T, Nagai K, Asaka M. Rikkunshito, an herbal medicine, suppresses cisplatin-induced anorexia in rats via 5-HT2 receptor antagonism. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:2004-2013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Oyachi N, Takano K, Hasuda N, Arai H, Koshizuka K, Matsumoto M. Effects of Rikkunshi-to on infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, refractory to atropine. Pediatr Int. 2008;50:581-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Targum SD, Hassman H, Pinho M, Fava M. Development of a clinical global impression scale for fatigue. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:370-374. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Khan A, Khan SR, Shankles EB, Polissarc NL. Relative sensitivity of the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, the Hamilton Depression rating scale and the Clinical Global Impressions rating scale in antidepressant clinical trials[J]. Int Clin Psychopharm. 2004;19:157-160. |

| 46. | Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiat Scand. 1983;67:361-370. |

| 47. | Tack J, Ly HG, Carbone F, Vanheel H, Vanuytsel T, Holvoet L, Boeckxstaens G, Caenepeel P, Arts J, Van Oudenhove L. Efficacy of Mirtazapine in Patients With Functional Dyspepsia and Weight Loss. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:385-392.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Knill-Jones RP. Geographical differences in the prevalence of dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1991;182:17-24. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Malagelada JR. Functional dyspepsia. Insights on mechanisms and management strategies. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1996;25:103-112. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Kellow JE. Motility-like dyspepsia. Current concepts in pathogenesis, investigation and management. Med J Aust. 1992;157:385-388. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Stanghellini V, Tosetti C, Paternico A, Barbara G, MorselliLabate AM, Monetti N, Marengo M, Corinaldesi R. Risk indicators of delayed gastric emptying of solids in patients with functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1036-1042. [PubMed] |