Published online Jul 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i27.4950

Peer-review started: March 17, 2017

First decision: April 20, 2017

Revised: May 3, 2017

Accepted: June 9, 2017

Article in press: June 12, 2017

Published online: July 21, 2017

Processing time: 126 Days and 13 Hours

To compare the efficacy of a session of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) before endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) vs ERCP only for problematic and large common bile duct (CBD) stones.

Adult patients with CBD stones for whom initial ERCP was unsuccessful because of the large size of CBD stones were identified. The patients were randomized into two groups, an “ESWL + ERCP group” and an “ERCP-only” group. For ESWL + ERCP cases, ESWL was performed prior to ERCP. Clearance of the CBD, complications related to the ESWL/ERCP procedure, frequency of mechanical lithotripsy use and duration of the ERCP procedure were evaluated in both groups.

There was no significant difference in baseline characteristics between the two groups. A session of ESWL before ERCP compared with ERCP only resulted in similar outcomes in terms of successful stone removal within the first treatment session (74.2% vs 71.0%, P = 0.135), but a higher clearance rate within the second treatment session (84.4% vs 51.6%, P = 0.018) and total stone clearance (96.0% vs 86.0%, P = 0.029). Moreover, ESWL prior to ERCP not only reduced ERCP procedure time (43 ± 21 min vs 59 ± 28 min, P = 0.034) and the rate of mechanical lithotripsy use (20% vs 30%, P = 0.025), but also raised the clearance rate of extremely large stones (80.0% vs 40.0%, P = 0.016). Post-ERCP complications were similar for the two groups.

Based on the higher rate of successful stone removal and minimal complications, ESWL prior to ERCP appears to be a safe and effective treatment for the endoscopic removal of problematic and large CBD stones.

Core tip: Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) are frequently used for patients with large common bile duct (CBD) stones. The effect of a session of ESWL prior to ERCP for problematic and large CBD stones has not previously been reported. The results of our research suggested that a session of ESWL can aid clearance of CBD in the following ERCP. Also mechanical lithotripsy usage was reduced and extremely large stone (≥ 30 mm) clearance rate can be raised.

- Citation: Tao T, Zhang M, Zhang QJ, Li L, Li T, Zhu X, Li MD, Li GH, Sun SX. Outcome of a session of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy before endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for problematic and large common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(27): 4950-4957

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i27/4950.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i27.4950

Therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was first introduced in the 1970s, and is the most frequently used endoscopic technique for the clearance of stones from the common bile duct (CBD)[1]. Conventional therapy for CBD stones involves sphincterotomy and stone extraction with either a Dormia basket or a Fogarty-type balloon[2]. About 80% to 90% of CBD stones can be extracted using conventional techniques[3]. Removal by ERCP is less invasive as compared with surgery but is more likely to fail when the stone is large[4,5]. For impacted or extremely large stones, or stones located intrahepatically or proximal to a bile duct stenosis, endoscopic removal may not be successful, and failure is generally due to the inability to grasp the large stones. In these patients, lithotripsy (electrohydraulic, electromagnetic or piezoelectric) has proved to be effective in terms of disintegrating stones into smaller fragments, facilitating the endoscopic clearance of CBD stones[6,7].

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) is a novel technique, which uses shock waves to fragment stones. Clinical experience with ESWL for the fragmentation of kidney stones was first reported in 1980[8]. Its application was quickly extended to large biliary and pancreatic stones. Sauerbruch and his colleagues demonstrated the efficacy of ESWL in achieving CBD stone fragmentation in about 90% of patients with mild side effects[9]. The present prospective controlled trial was conducted to compare the therapeutic benefits and complications in patients having a session of ESWL before ERCP and patients having ERCP alone for the treatment of problematic and large CBD stones.

This prospective study was conducted at the Department of Gastroenterology of Zibo Central Hospital, a tertiary referral hospital in Zibo, Shandong Province, China. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Zibo Central Hospital. All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

From February 2013 to September 2016, 231 eligible patients were identified at the hospital. The inclusion criteria were adult patients with CBD stones who had undergone an unsuccessful initial ERCP. A nasobiliary tube (NBT) was placed in all subjects to irrigate the stones and visualize the calculi during ESWL. The number and diameter of the stones were assessed by pre-ESWL X-ray or computed tomography. If multiple stones were detected, the largest single stone diameter was tallied. Patients were treated with a session of ESWL (14-26 kV) before ERCP in the ESWL + ERCP group.

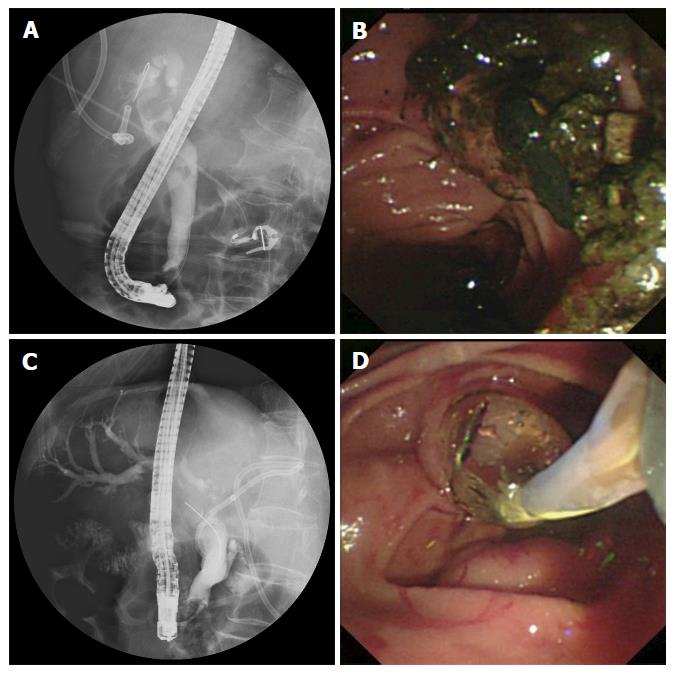

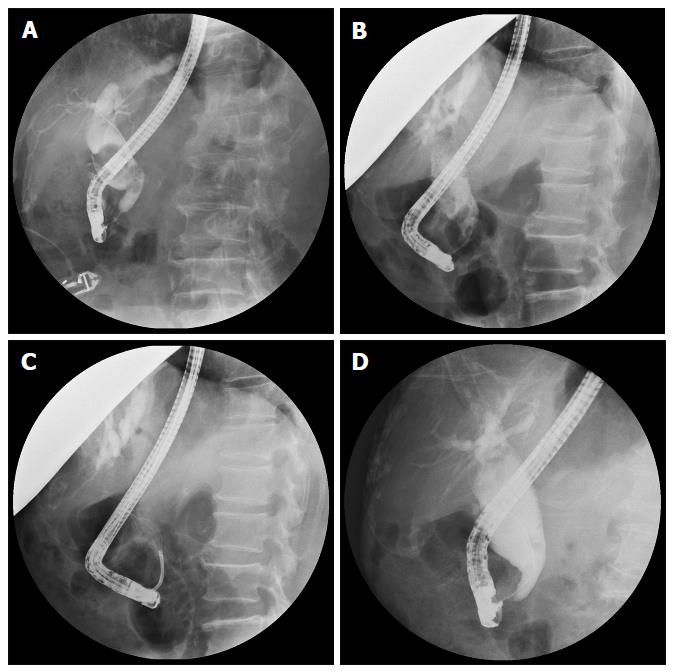

Patients who were admitted on Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday were allocated to the ERCP-only group. These patients underwent conventional ERCP treatment for stone extraction using a side-view endoscope (JF-240; Olympus Optical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), performed by two senior endoscopists, each with the experience of more than 1000 ERCP procedures. Patients admitted on Friday, Saturday, Sunday and Monday were allocated to the ESWL + ERCP group. For these patients, a session of ESWL was performed 4 h before ERCP by experienced gastroenterologists using an electrohydraulic spark gap lithotripter (HealthTronics, Austin, TX, United States), even if no difficulty was anticipated in the following ERCP procedure in terms of removing the stones by means of basket extraction. Patients were treated in the prone position and under general anaesthesia with continuous monitoring. Stones were localized and targeted with an X-ray focusing system. ESWL was performed at a rate of 90 shocks/min for 10 min and at an intensity of 4 (on a scale of 1-6, corresponding to 11000-16000 kV). Patients were exposed to a maximum of 5000 shocks/session unless the stones were fragmented to less than 5 mm earlier. ERCP was performed 4 h after ESWL to clear the fragments using a retrieval basket or balloon catheter, unless the stones passed spontaneously. If present, CBD strictures were dilated using a balloon (4-15 mm), and passage dilating catheters were used to retrieve the stones (Figure 1). In cases where CBD stones could not be cleared successfully in two treatment sessions, the patient would be subjected to repeated biliary stenting or surgery.

CBD stone clearance was assessed after each ERCP session using procedure reports, plain films, ERCP films and/or abdominal MRCP (Figure 2). Separate records were made for each group that included information on post-ESWL complications, post-ERCP complications, number of mechanical lithotripsies used and the duration of each ERCP procedure. Post-ERCP complications were recorded in all patients and graded as mild, moderate or severe according to Cotton’s criteria[10]. Successful clearance was defined as the clearance of more than 90% of the CBD stone fragments using a balloon or a basket.

The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by a biostatistician (Jia-Tong Liang) from Shandong University of Technology. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for non-continuous variables, and Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables. Analyses were performed by using SPSS 12.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States). A probability (P) value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Two hundred and thirty-one patients were evaluated in this study (ESWL + ERCP group, n = 124; ERCP-only group, n = 107). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in clinical characteristics between the two groups including prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (1.14 ± 0.22 vs 1.19 ± 0.34, P = 0.382), periampullary diverticulum (43.5% vs 44.9%, P = 0.263), pre-cut sphincterotomy (52.4% vs 56.1%, P = 0.187), stone size (18.3 ± 2.5 mm vs 16.6 ± 3.8 mm, P = 0.084), and the percentage of patients who have had multiple stones (33.1% vs 32.7%, P = 0.371) or extremely large (> 3.0 cm) stones (12.1% vs 9.3%, P = 0.195).

| Demographic characteristic | ESWL + ERCP (n = 124) | ERCP only (n = 107) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 71.2 ± 4.6 | 68.4 ± 6.1 | 0.647 |

| Male | 63 (50.8) | 56 (52.3) | 0.318 |

| Prothrombin time/INR | 1.14 ± 0.22 | 1.19 ± 0.34 | 0.382 |

| Periampullary diverticulum | 54 (43.5) | 48 (44.9) | 0.263 |

| Pre-cut sphincterotomy | 65 (52.4) | 60 (56.1) | 0.187 |

| Calculi characteristic | |||

| Single | 83 | 72 | |

| Multiple | 41 (33.1) | 35 (32.7) | 0.371 |

| Stone size | 18.3 ± 2.5 | 16.6 ± 3.8 | 0.084 |

| 1.5-3.0 cm | 104 | 93 | |

| > 3.0 cm | 15 (12.1) | 10 (9.3) | 0.195 |

Stones passed spontaneously in six patients during ESWL treatment, in four patients during the first session and in two patients during the second session. Overall, there were 156 ESWLs and 150 ERCPs in the 124 patients in the ESWL + ERCP group, whereas there were 138 ERCPs in the 107 patients of the ERCP-only group. The outcome of the two groups is summarized in Table 2. In the first session, successful stone clearance did not differ significantly between the two groups (74.2% vs 71%, P = 0.135). However, in the second session, ESWL before ERCP produced a higher stone clearance than that observed in the ERCP-only group (84.4% vs 51.6%, P = 0.018), and the overall stone clearance also differed significantly (96.0% vs 86.0%, P = 0.029) between the two groups. Moreover, a session of ESWL before ERCP reduced the rate of mechanical lithotripsy (20.0% vs 30.0%, P = 0.025) and ERCP procedure time (43 ± 21 min vs 59 ± 28 min, P = 0.034). Successful stone removal by a conventional method (balloon or dormia basket) was similar between the two groups (97.0% vs 91.5%, P = 0.251); however, successful clearance rate of mechanical lithotripsy differed significantly (92.0% vs 75.0%, P = 0.041). Removal of extremely large-sized stones (≥ 3.0 cm) differed significantly between the groups [80.0% (12/15) in the ESWL + ERCP group vs 40.0% (4/10) in the ERCP-only group, P = 0.016] (Table 3).

In 20 patients, stones had not been extracted even after two sessions of treatment (5 patients in the ESWL + ERCP group and 15 patients in the ERCP-only group). Failure was due to either distal CBD strictures or patient intolerance, and thus these patients were subjected to repeated stenting or surgical treatment. No additional data are available.

Post-ERCP complication rates were similar in the two groups (6.7% vs 6.5%, P = 0.673). Complications included pancreatitis (3.3% vs 3.6%, P = 0.357), cholangitis (2.0% vs 2.2%, P = 0.218) and haemorrhage (1.9% vs 0.7%, P = 0.074; Table 4). Complications were mild with no serious consequences. Some patients experienced discomfort related to the presence of the NBT, but this was not recorded as a complication. Pancreatitis and haemorrhage required hospitalization for 1-3 d, while cholangitis was resolved with antibiotic therapy. Intensive care or surgery was not required for any of the patients. Complications related to ESWL (11 cases, 7.0%) included purpuric spots (5 cases, 3.2%) and skin ecchymosis (6 cases, 3.8%). These patients required no treatment and the symptoms generally disappeared within a week. Severe complications such as splenic rupture, ductal perforation and necrotizing pancreatitis did not occur. There was no procedure-related mortality among these patients.

| Complication | ESWL + ERCP | ERCP only | P value |

| Post-ERCP | 10/150 (6.7) | 9/138 (6.5) | 0.673 |

| Pancreatitis (mild) | 5/150 (3.3) | 5/138 (3.6) | 0.357 |

| Cholangitis (mild) | 3/150 (2.0) | 3/138 (2.2) | 0.218 |

| Hemobilia (mild) | 2/150 (1.9) | 1/138 (0.7) | 0.074 |

| Bowel perforation | 0 | 0 | |

| Procedure-related mortality | 0 | 0 | |

| Post-ESWL | 11/156 (7.0) | ||

| Purpuric spots | 5/156 (3.2) | ||

| Skin ecchymosis | 6/156 (3.8) | ||

| Splenic rupture | 0 | ||

| Lung trauma | 0 | ||

| Necrotizing pancreatitis | 0 | ||

| Procedure-related mortality | 0 |

CBD stones may cause jaundice, cholangitis, pruritus and biliary pancreatitis. The prevalence of CBD stones increases with age and treatment is difficult. At present, surgical choledochotomy is no longer always the therapy of choice due to its invasive character and associated morbidity and mortality. Since the introduction of therapeutic ERCP in 1974, there has been much progress regarding this procedure for treating CBD stones[11]. However, in clinical practice it is not uncommon to see patients with large CBD stones, which cannot be removed by such conventional techniques. For difficult cases, various adjuvant treatments such as ESWL, electrohydraulic lithotripsy and lasers are recommended rather than just using a mechanical lithotripter[12].

Kidney lithotriptors can be used when performing ESWL of bile duct stones, and its efficacy in treating CBD stones has been reported in many studies[13,14]. But for some difficult cases, fragmentation alone may not be adequate because of size and other reasons[15]. Many researchers advised performing ERCP after ESWL to facilitate ductal clearance and decompression, clearing fragments and to address any ductal strictures by balloon dilation with or without stenting[16]. Tao et al[17] reported that using cholecystokinin during ESWL can facilitate endoscopic clearance of large CBD stones. Therefore, ESWL overcomes the problem of the stone size by fragmenting the stones and reducing the stone burden, thus facilitating endoscopic clearance in the following ERCP procedure. According to the literature, complete clearance of CBD stones can be achieved in 40%-75% of the patients[18,19].

Tandan et al[20] reported improved stone clearance of large CBD stones using ESWL prior to ERCP. In the study, patients with large CBD stones were subjected to up to 7 ESWL sessions before CBD stones were decomposed to fragments less than 5 mm in diameter. The authors concluded that stones were best fragmented at a kV intensity of 4 (range, 1 to a maximum of 6, corresponding to 11000-16000 kV) and a frequency of 90 shocks/min. Patients were subjected to ESWL at a shock wave frequency of 90/min with continuous saline irrigation contributing to the complete fragmentation of CBD stones.

In our study, patients in the ESWL + ERCP group were subjected to an ESWL session 4 h prior to ERCP. The stones may or may not have been fragmented to a size less than 5 mm in diameter; however, in each case the following ERCP was performed as planned. The results were satisfactory. Although the rate of successful CBD clearance was similar in the first treatment session between the two groups (74.2% vs 71%, P = 0.135), a session of ESWL prior to ERCP showed a higher clearance rate in the second treatment session (84.4% vs 51.6%, P = 0.018) and in the overall outcome (96.0% vs 86.0%, P = 0.029). The rate of mechanical lithotripsy use also differed between the two groups (20% vs 30%, P = 0.025), potentially accounting for the statistical difference observed in the relative duration of ERCP (43 ± 21 min vs 59 ± 28 min, P = 0.034). Using the conventional methods (balloon or basket), stone clearance was high in both groups, while the removal of extremely large stones and successful clearance rates of mechanical lithotripsy differed significantly between the two groups (20% vs 30%, P = 0.025; and 92.0% vs 75.0%, P = 0.041, respectively). Although these differences might be due to various factors, such as the extent of ERCP, the size of the stone and the dilating balloon, the shape of the stone and the bile duct, we think that including a session of ESWL prior to ERCP is an important tool for reducing the rate of mechanical lithotripsy use and ERCP procedure time. In addition, it shows promise in terms of improving the clearance rate of extremely large stones.

In previous studies, stone fragmentation and clearance were influenced by the presence of a downstream stricture, stone size and location[21]. In our study, there was no significant difference in complete CBD stone clearance according to stone size or location, or accompanying downstream stricture. Strictures in the CBD were dilated using balloons in nearly all the cases. Such procedures did not have any negative impact on stone clearance in our study. Several authors reported that a stent should be placed for bile drainage if CBD stones could not be removed in the first session of ESWL[22-24]. Biliary stent placement has been established as a convenient and minimally invasive treatment for difficult stones, and we adopted it in our series.

Post-ERCP complications such as moderate pancreatitis, cholangitis and mild haemorrhage were similar in the two groups and are consistent with previous reports[25,26]. Post-ERCP pancreatitis is the most common complication of ERCP despite technological developments and improved endoscopist skill levels. The possible causes of the low rate of pancreatitis observed in the present study include proper patient selection for ERCP with appropriate indications and guidewire cannulation[27]. In our study, the presence of NBT helped us selectively cannulate CBD when performing ERCP, thus avoiding cannulating and excessive injection of the CBD. There was no increased incidence of pancreatitis after ERCP in the ESWL + ERCP group.

A number of rare and serious complications have been reported following ESWL[28-31]. These include perirenal hematoma, biliary obstruction, bowel perforation, splenic rupture, lung trauma and necrotizing pancreatitis. These severe complications did not occur in our study, probably because of accurate targeting achieved by the third-generation lithotripter and reduced patient movement. Pain at the site of shock wave delivery, skin ecchymosis, abdominal pain, occasional fever and hemobilia were observed in some of our patients. These complications were mild and minimal, all being managed conservatively without extension of hospital stay.

A recurrence rate of 14% for post-ESWL CBD calculi at 1-year follow-up has been reported[32]. Therefore, stones should be removed as completely as possible. In our study we found that saline irrigation is helpful and should be repeated several times until all the bile drainage is completely clean.

ESWL appears to be a valid, low-cost technique applicable to challenging bile duct stones and its utilization may be extended to urology. Hence, the same device can be used by different medical staff in hospitals, thus reducing management costs.

The main limitation of our study was that we evaluated short-term outcomes, such as successful clearance in the first and second session of ESWL + ERCP and complications of the procedure. However, long-term follow-up of the failed cases was not evaluated and included in this study. Second, the interpretation of the degree of CBD clearance could be subjective. Also, the treatment effect may be influenced by the skills of the treating physician. Other limitations include performing the study at only one centre and the relatively small number of patients. Further prospective randomized studies are therefore needed to prove efficacy and evaluate cost efficacy.

In conclusion, a session of ESWL prior to ERCP is an excellent therapeutic modality for problematic and large common bile duct stones, offering a high clearance rate, particularly in terms of removing extremely large CBD stones. This procedure moreover reduces the use of mechanical lithotripsy and ERCP procedure time. Therefore, we propose that a session of ESWL prior to ERCP is an effective and safe treatment for endoscopic removal of challenging and large CBD stones.

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) uses electromagnetic waves to fragment problematic and large bile duct stones when endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) fails. Fragmentation was considered satisfactory when the stones were broken down to < 5 mm diameter. For the patients in whom initial ERCP was unsuccessful, a session of ESWL before ERCP may aid the clearance of common bile duct stones.

The results obtained with third generation electromagnetic lithotripters are optimal; however, technological improvements in lithotripters and other factors favoring stone fragmentation may further enhance our performance.

The authors’ work emphasizes, in a wide patient population, that a session of ESWL before ERCP is a safe and effective method to the clearance of bile duct stones, and problematic and large common bile duct stone removal rate was higher in the final outcome. Also mechanical lithotripsy usage was reduced.

The study is of interest for physicians dealing with the common bile duct stones and particularly those managing problematic and large stone that failed in the first ERCP procedure. Based on these results, a session of ESWL before ERCP was confirmed to be helpful in the treatment of problematic and large common bile duct stones.

Mechanical lithotripsy is an effective method of fragmenting stones in the bile duct. Retrieval basket, balloon catheter or passage dilating catheters are usual methods to retract stones and dilate bile duct to facilitate endoscopic clearance of stones.

Overall, the study helps to evaluate the outcome of a session of ESWL before ERCP in treatment of problematic and large common bile duct stones.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Yildiz K, Yin HK S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Kawai K, Akasaka Y, Murakami K, Tada M, Koli Y. Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the ampulla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc. 1974;20:148-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in RCA: 453] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Binmoeller KF, Schafer TW. Endoscopic management of bile duct stones. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:106-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fujita N, Maguchi H, Komatsu Y, Yasuda I, Hasebe O, Igarashi Y, Murakami A, Mukai H, Fujii T, Yamao K. Endoscopic sphincterotomy and endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation for bile duct stones: A prospective randomized controlled multicenter trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:151-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Adamek HE, Maier M, Jakobs R, Wessbecher FR, Neuhauser T, Riemann JF. Management of retained bile duct stones: a prospective open trial comparing extracorporeal and intracorporeal lithotripsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:40-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ellis RD, Jenkins AP, Thompson RP, Ede RJ. Clearance of refractory bile duct stones with extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy. Gut. 2000;47:728-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Leung JW, Neuhaus H, Chopita N. Mechanical lithotripsy in the common bile duct. Endoscopy. 2001;33:800-804. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Leung JW, Tu R. Mechanical lithotripsy for large bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:688-690. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Chaussy C, Brendel W, Schmiedt E. Extracorporeally induced destruction of kidney stones by shock waves. Lancet. 1980;2:1265-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 826] [Cited by in RCA: 706] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sauerbruch T, Stern M. Fragmentation of bile duct stones by extracorporeal shock waves. A new approach to biliary calculi after failure of routine endoscopic measures. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:146-152. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2035] [Article Influence: 59.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Brady PG, Pinkas H, Pencev D. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Dig Dis. 1996;14:371-381. |

| 12. | Binmoeller KF, Brückner M, Thonke F, Soehendra N. Treatment of difficult bile duct stones using mechanical, electrohydraulic and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Endoscopy. 1993;25:201-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Muratori R, Azzaroli F, Buonfiglioli F, Alessandrelli F, Cecinato P, Mazzella G, Roda E. ESWL for difficult bile duct stones: a 15-year single centre experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4159-4163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kocdor MA, Bora S, Terzi C, Ozman I, Tankut E. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for retained common bile duct stones. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2000;9:371-374. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | González-Koch A, Nervi F. Medical management of common bile duct stones. World J Surg. 1998;22:1145-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sackmann M, Holl J, Sauter GH, Pauletzki J, von Ritter C, Paumgartner G. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for clearance of bile duct stones resistant to endoscopic extraction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:27-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tao T, Zhang QJ, Zhang M, Zhu X, Sun SX, Li YQ. Using cholecystokinin to facilitate endoscopic clearance of large common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10121-10127. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Tandan M, Reddy DN. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for pancreatic and large common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4365-4371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Cecinato P, Fuccio L, Azzaroli F, Lisotti A, Correale L, Hassan C, Buonfiglioli F, Cariani G, Mazzella G, Bazzoli F. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for difficult common bile duct stones: a comparison between 2 different lithotripters in a large cohort of patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:402-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tandan M, Reddy DN, Santosh D, Reddy V, Koppuju V, Lakhtakia S, Gupta R, Ramchandani M, Rao GV. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy of large difficult common bile duct stones: efficacy and analysis of factors that favor stone fragmentation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1370-1374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Heo JH, Kang DH, Jung HJ, Kwon DS, An JK, Kim BS, Suh KD, Lee SY, Lee JH, Kim GH. Endoscopic sphincterotomy plus large-balloon dilation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of bile-duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:720-776; quiz 768, 771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bergman JJ, Rauws EA, Tijssen JG, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Biliary endoprostheses in elderly patients with endoscopically irretrievable common bile duct stones: report on 117 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:195-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Maxton DG, Tweedle DE, Martin DF. Retained common bile duct stones after endoscopic sphincterotomy: temporary and longterm treatment with biliary stenting. Gut. 1995;36:446-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hong WD, Zhu QH, Huang QK. Endoscopic sphincterotomy plus endoprostheses in the treatment of large or multiple common bile duct stones. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:240-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Huibregtse K. Complications of endoscopic sphincterotomy and their prevention. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:961-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wojtun S, Gil J, Gietka W, Gil M. Endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis: a prospective single-center study on the short-term and long-term treatment results in 483 patients. Endoscopy. 1997;29:258-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Li X, Tao LP, Wang CH. Effectiveness of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12322-12329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hirata N, Kushida Y, Ohguri T, Wakasugi S, Kojima T, Fujita R. Hepatic subcapsular hematoma after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) for pancreatic stones. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:713-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Leifsson BG, Borgström A, Ahlgren G. Splenic rupture following ESWL for a pancreatic duct calculus. Dig Surg. 2001;18:229-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Plaisier PW, den Hoed PT. Splenic abscess after lithotripsy of pancreatic duct stones. Dig Surg. 2001;18:231-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Karakayali F, Sevmiş S, Ayvaz I, Tekin I, Boyvat F, Moray G. Acute necrotizing pancreatitis as a rare complication of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Int J Urol. 2006;13:613-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Trikudanathan G, Navaneethan U, Parsi MA. Endoscopic management of difficult common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:165-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |