Published online Jul 7, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i25.4595

Peer-review started: March 26, 2017

First decision: April 7, 2017

Revised: April 10, 2017

Accepted: June 1, 2017

Article in press: June 1, 2017

Published online: July 7, 2017

Processing time: 105 Days and 22.5 Hours

To compare the short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic (LR) vs open resection (OR) for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors (gGISTs).

In total, 301 consecutive patients undergoing LR or OR for pathologically confirmed gGISTs from 2005 to 2014 were enrolled in this retrospective study. After exclusion of 77 patients, 224 eligible patients were enrolled (122 undergoing LR and 102 undergoing OR). The demographic, clinicopathologic, and survival data of all patients were collected. The intraoperative, postoperative, and long-term oncologic outcomes were compared between the LR and OR groups following the propensity score matching to balance the measured covariates between the two groups.

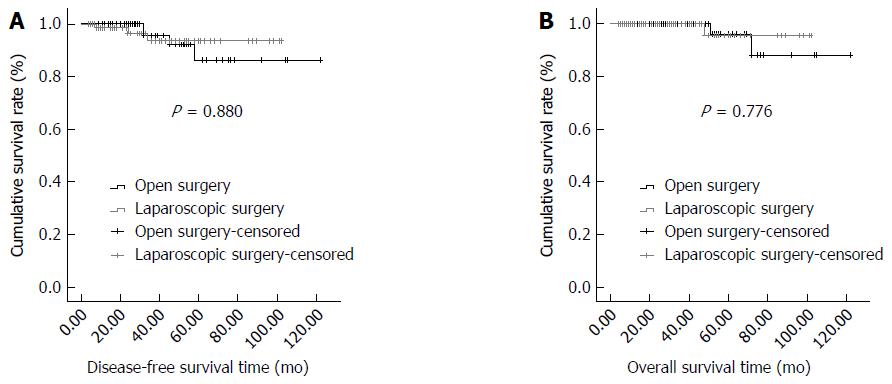

After 1:1 propensity score matching for the set of covariates including age, sex, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiology score, tumor location, tumor size, surgical procedures, mitotic count, and risk stratification, 80 patients in each group were included in the final analysis. The baseline parameters of the two groups were comparable after matching. The LR group was significantly superior to the OR group with respect to the operative time, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative first flatus, time to oral intake, and postoperative hospital stay (P < 0.05). No differences in perioperative blood transfusion or the incidence of postoperative complications were observed between the two groups (P > 0.05). No significant difference was found in postoperative adjuvant therapy (P = 0.587). The mean follow-up time was 35.30 ± 26.02 (range, 4-102) mo in the LR group and 40.99 ± 25.07 (range, 4-122) mo in the OR group with no significant difference (P = 0.161). Survival analysis showed no significant difference in the disease-free survival time or overall survival time between the two groups (P > 0.05).

Laparoscopic surgery for gGISTs is superior to open surgery with respect to intraoperative parameters and postoperative outcomes without compromising long-term oncological outcomes.

Core tip: Surgical treatment is the gold standard for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors (gGISTs). Increasingly more surgeons are performing laparoscopic resection (LR) to treat gGISTs due to the development and superiority of laparoscopic technology. The efficacy and safety of LR remain unconfirmed and more high-level clinical evidence is required. This study retrospectively compared the short- and long-term outcomes of LR vs open resection (OR) for gGISTs using propensity score matching to adjust for confounding variables in the baseline data and found that LR is superior to OR with respect to intraoperative parameters and postoperative recovery outcomes without compromising long-term oncological outcomes.

- Citation: Ye X, Kang WM, Yu JC, Ma ZQ, Xue ZG. Comparison of short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic vs open resection for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(25): 4595-4603

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i25/4595.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i25.4595

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal neoplasms of the alimentary system and exhibit high resistance to conventional chemotherapy or radiotherapy[1]. The incidence of GISTs has gradually increased in recent years with the development of histologic and immunohistochemical markers for diagnosis and advances in radiographic technology and endoscopic examination[2]. The widespread use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors has significantly improved the survival of patients with GISTs[2]. However, surgical resection is still the mainstay and most effective treatment for GISTs to date. GISTs should be completely resected with negative histological margins, and the tumor pseudocapsule should be kept intact to avoid tumor rupture during the operation[3]. Because lymphatic metastasis rarely occurs in patients with GISTs, lymphadenectomy is not routinely performed[4].

About 50%-60% of GISTs occur in the stomach[5], and these gastric GISTs (gGISTs) are mainly located in the upper stomach[6]. Localized gGISTs were traditionally resected by open resection (OR)[7]. Increasingly more surgeons are performing laparoscopic resection (LR) to treat gGISTs because of the development and superiority of laparoscopic technology. The first successful LR of a gGIST was reported by Lukaszczyk and Preletz in 1992[8]. Several laparoscopic approaches for gGISTs are available, including wedge resection, proximal or distal subtotal gastrectomy, and total gastrectomy[7]. Intraoperative gastroscopy is usually used to help define the tumor location because the surgical approach depends on the tumor size and location. Tumor rupture is an independent prognostic factor for GISTs. Once a GIST has ruptured into the abdominal cavity, the risk of tumor recurrence and implantation metastasis become extremely high[9]. Because of the risk of tumor rupture, the application of a laparoscopic approach for gGISTs is restricted, especially for large tumors[10]. In some guidelines, LR of GISTs remains a cautious choice and is only recommended when performed by expert surgeons[11]. The 2016 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline suggests that laparoscopic surgery may be considered for GISTs in selected anatomic locations such as the anterior wall of the stomach, jejunum, and ileum. LR should follow the same principles of preservation of the pseudocapsule and avoidance of tumor rupture, just as OR[12]. Additionally, the previous NCCN guideline recommends the use of laparoscopic techniques for GISTs < 5 cm[13].

Whether LR can achieve equivalent effects or even show superiority over conventional OR remains unknown[14]. No prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trials with sufficient samples have been performed to investigate the feasibility and safety of LR for gGISTs because of the low incidence of these tumors. To date, only a few retrospective studies have compared LR with OR for gGISTs, and the efficacy and safety of LR remain unconfirmed[15]. Therefore, more high-level clinical evidence is required.

The existence of confounders or selection bias in retrospective studies may result in imbalanced baseline data between the study group and control group; this consequently affects the reliability of the conclusions. In nonrandomized controlled clinical trials, epidemiological studies, and most observational studies, propensity score matching (PSM) is widely used to reduce selection bias caused by potential confounders and ensure that the baseline data are balanced[16]. In the present study, we retrospectively compared the short- and long-term outcomes of LR vs OR of gGISTs using PSM to adjust for confounding variables in the baseline data.

In total, 301 consecutive patients who underwent surgical treatment for pathologically diagnosed gGISTs from 2005 to 2014 were primarily extracted from our prospectively maintained GIST database. Sixty-nine patients were excluded for the following reasons: (1) comorbidities involving other types of malignant tumors either present preoperatively or found intraoperatively; (2) a history of upper abdominal surgery or gastrectomy; (3) thoracotomy for GISTs involving the cardia or lower esophagus; (4) intraoperative confirmation of hepatic or peritoneal metastasis; (5) combined organ resection for involvement of adjacent organs; (6) an emergency operation for bleeding or perforation; (7) death during the operation; and (8) endoscopic resection. Because the largest tumor resected by a laparoscopic approach was 14 cm, eight patients with tumors > 14 cm (range, 16-29 cm) undergoing OR were excluded. Finally, 224 patients were enrolled in the subsequent PSM analysis, including 102 patients undergoing LR (treatment group, LR group) and 122 patients undergoing OR (control group, OR group).

All 224 patients were clinically suspected to have gGISTs based on preoperative gastroscopy, abdominal computed tomography, or endoscopic ultrasonography findings, and a diagnosis of gGIST was confirmed by postoperative pathologic examination in all patients. The following clinical data were collected: (1) demographic characteristics including age, sex, and body mass index (BMI); (2) clinical and operation-related data including the American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) score, tumor location, type of surgical procedure, operative time, intraoperative blood loss, perioperative blood transfusion, time to postoperative first flatus, time to oral intake, postoperative length of hospital stay, postoperative complications, and adjuvant therapy; (3) histopathological data including tumor size, mitotic count, and stratification of risk of recurrence; and (4) prognostic information including follow-up duration, recurrence, and death. The tumor location was divided into three types: the gastric fundus and cardiac surroundings, the gastric body, and the gastric antrum and pyloric surroundings. The severity of postoperative complications was classified according to the Clavien-Dindo classification, and only grade ≥ 2 complications were considered for the morbidity analysis[17]. Stratification of the risk of recurrence was performed according to the 2008 National Institutes of Health standard[18].

LR of gGISTs was initiated in our hospital in 2005. OR was historically more popular, but LR has become preferred with its extensive development and the accumulation of experience in the last decade. The operations were performed by gastrointestinal surgeons experienced in both open and minimally invasive surgery. OR was performed through a 15- to 20-cm subxiphoid incision, and LR was performed by a four- or five-trocar method. The abdominal cavity was first inspected to identify the tumor location and rule out invasion to adjacent organs or distant metastases. The methods of tumor resection were similar in both the LR and OR groups and included wedge resection, proximal gastrectomy, distal gastrectomy, and total gastrectomy depending on the tumor location, size, and distance to the cardia or pylorus. Lymphadenectomy was not routinely performed. Intraoperative gastroscopy was applied to define the tumor localization when the tumor was small or intracavitary. Linear and circular staplers were frequently used. Laparoscopic gastrectomy was performed via a 5- to 7-cm epigastric incision with hand-assisted anastomosis. In patients undergoing LR, the tumor specimen was removed using an extracting bag. All patients in this study achieved R0 resection without tumor rupture. No forced conversion to laparotomy occurred among patients undergoing LR.

Imatinib therapy was recommended for patients with intermediate or high risk stratification. Follow-up was conducted at the outpatient clinic, telephone calls, or letters. The last follow-up occurred in May 2015. The follow-up data included adjuvant therapy, survival time, tumor recurrence, and death.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). The χ2 test was used to analyze categorical data, and Student’s t test was used for continuous data. PSM was used to match covariates between the LR and OR groups. These covariates included age, sex, BMI, ASA score, tumor location, tumor size, surgical procedure, mitotic count, and risk stratification. The propensity score was estimated using a multivariate logistic regression model based on this set of covariates for each patient. All patients in the LR group were then matched 1:1 to those in the OR group by nearest neighbor matching. A caliper was used to define the maximum allowable difference (0.3) between two groups to ensure good matches. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to create a survival curve, and the log-rank test was used to detect differences between the two groups. All statistical tests were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In total, 224 patients were included in the primary analysis before PSM, and their clinicopathological characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 59.25 ± 11.63 (range, 21-82) years, and 55.80% of patients were ≤ 60 years old. Female patients accounted for 57.14% of all patients. The mean BMI was 24.08 ± 3.08 (range, 15.60-32.81) kg/m2, and 90.18% of patients had a BMI of < 28 kg/m2. Patients with an ASA score of I and II constituted 95.08% of all patients. And 49.11% of tumors were located in the proximal stomach and 38.84% were located in the body of the stomach. A total of 68.75% of tumors had a maximum diameter of ≤ 5 cm, and 82.59% of all patients received wedge resection. Patients with a moderate and high risk of recurrence accounted for 45.54% of the study population. Before PSM, there were no significant differences in age, sex, BMI, or ASA score between the two groups (P > 0.05), but significant differences were present in other parameters (P < 0.05). Compared with the LR group, OR group had more tumors in the body of the stomach and distal stomach, more tumors with a maximum diameter of > 5 cm, underwent subtotal gastrectomy more often, and had more tumors with a mitotic count of > 5/PHF and intermediate/high risk of recurrence (P < 0.05). After PSM, 22 patients in the LR group and 42 patients in the OR group were excluded, and 80 patients in each group were included in the final PSM analysis. No statistically significant differences in any covariate were found between the two groups after PSM (P > 0.05).

| Characteristics | Before PSM | After PSM | ||||

| LR group (n = 102) | OR group (n = 122) | P value | LR group (n = 80) | OR group (n = 80) | P value | |

| Age, yr | ||||||

| > 60 | 45 | 54 | 0.983 | 39 | 35 | 0.526 |

| ≤ 60 | 57 | 68 | 41 | 45 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 43 | 53 | 0.846 | 36 | 33 | 0.632 |

| Female | 59 | 69 | 44 | 47 | ||

| BMI , kg/m2 | ||||||

| < 28 | 92 | 110 | 0.994 | 75 | 72 | 0.385 |

| ≥ 28 | 10 | 12 | 5 | 8 | ||

| ASA score | ||||||

| I | 57 | 73 | 0.825 | 43 | 48 | 0.722 |

| II | 40 | 43 | 32 | 28 | ||

| III | 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | ||

| Tumor location | ||||||

| Proximal | 61 | 49 | 0.014 | 47 | 36 | 0.141 |

| Body | 31 | 56 | 24 | 36 | ||

| Antropyloric | 10 | 17 | 9 | 8 | ||

| Tumor size, cm | ||||||

| ≤ 5 | 83 | 71 | 0.001 | 61 | 57 | 0.633 |

| 5-10 | 17 | 40 | 17 | 19 | ||

| > 10 | 2 | 11 | 2 | 4 | ||

| Surgical procedure | ||||||

| Wedge resection | 96 | 89 | 0.000 | 74 | 69 | 0.200 |

| Gastrectomy | 6 | 33 | 6 | 11 | ||

| Mitotic count | ||||||

| ≤ 5 | 84 | 83 | 0.002 | 62 | 59 | 0.090 |

| 6-10 | 5 | 26 | 5 | 13 | ||

| > 10 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 8 | ||

| Risk stratification | ||||||

| Very low | 34 | 9 | 0.000 | 15 | 9 | 0.485 |

| Low | 37 | 42 | 34 | 37 | ||

| Intermediate | 16 | 39 | 16 | 21 | ||

| High | 15 | 32 | 15 | 13 | ||

The intraoperative and postoperative outcomes after PSM are shown in Table 2. The LR group was significantly superior to the OR group with respect to the operative time, intraoperative blood loss, time to first flatus, time to oral intake, and postoperative length of hospital stay (P < 0.05), while no differences were present in perioperative blood transfusion (P > 0.05). No differences in the incidence of postoperative complications were observed between the two groups (5.00% in the LR group and 11.25% in the OR group; P > 0.05).

| Characteristics | LR group (n = 80) | OR group (n = 80) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Operative time (min) | 90.83 ± 37.69 | 118.38 ± 42.74 | 4.325 | 0.000 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 91.88 ± 65.82 | 121.25 ± 103.05 | 2.149 | 0.033 |

| Perioperative blood transfusion | ||||

| No | 79 | 77 | 1.026 | 0.620 |

| Yes | 1 | 3 | ||

| Time to first flatus (d) | 2.63 ± 0.62 | 3.01 ± 0.46 | 4.459 | 0.000 |

| Time to oral intake (d) | 3.86 ± 1.17 | 5.24 ± 5.04 | 2.377 | 0.019 |

| Length of hospital stay (d) | 9.26 ± 3.89 | 11.73 ± 9.34 | 2.176 | 0.031 |

| Complications1 | ||||

| No | 95% (76/80) | 88.75% (71/80) | 2.093 | 0.247 |

| Yes | 5% (4/80) | 11.25% (9/80) |

The adjuvant therapy and oncological outcomes in the LR and OR groups after PSM are shown in Table 3. There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients who received postoperative imatinib between the LR and OR groups (27.50% vs 23.75%, respectively; P > 0.05). The mean follow-up time was 35.30 ± 26.02 (range, 4-102) mo in the LR group and 40.99 ± 25.07 (range, 4-122) mo in the OR group, with no significant difference (P > 0.05). There were no significant differences between the LR and OR groups in the number of patients with recurrence (3 vs 4, respectively; P > 0.05) or died (1 vs 2, respectively; P > 0.05). Additionally, no significant differences were found in the disease-free survival (DFS) time or overall survival (OS) time (P > 0.05). No significant differences were present between the LR and OR groups in the 5-year DFS rate (97.50% vs 96.25%, respectively; P > 0.05) or 5-year OS rate (98.75% vs 98.75%, respectively; P > 0.05). The Kaplan-Meier DFS and OS curves are shown in Figure 1A and B, respectively.

| Characteristics | LR group (n = 80) | OR group (n = 80) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||||

| No | 58 | 61 | 0.295 | 0.587 |

| Yes | 22 | 19 | ||

| Follow-up time (mo) | 35.3 ± 26.02 | 40.99 ± 25.07 | 1.408 | 0.161 |

| Recurrence | ||||

| No | 77 | 76 | 0.149 | 0.699 |

| Yes | 3 | 4 | ||

| Death | ||||

| No | 79 | 78 | 0.340 | 0.560 |

| Yes | 1 | 2 | ||

| DFS time (mo)1 | 97.04 ± 2.81 | 111.61 ± 5.12 | 0.023 | 0.880 |

| 5-yr DFS rate (%)2 | 97.5 (78/80) | 96.25 (77/80) | 1.000 | |

| OS time (mo)1 | 99.65 ± 2.30 | 115.26 ± 4.59 | 0.081 | 0.776 |

| 5-yr OS rate (%)2 | 98.75 (79/80) | 98.75 (79/80) | 1.000 |

Surgical treatment is the gold standard for gGISTs[2]. Unlike other types of malignant tumors requiring a sufficient distance to the incisal margin and performance of lymphadenectomy, GISTs only require the achievement of R0 resection, and lymphadenectomy is not necessary. Therefore, LR seems to be more applicable than OR for patients with GISTs[15]. Compared with conventional OR, LR shows advantages including less trauma, lower stress, less pain, and faster recovery. These advantages have been proven in several gastrointestinal surgeries, including laparoscopic surgeries for gastric and colorectal cancer. Laparoscopic gastrointestinal surgery can benefit the recovery of intestinal motility, promote early flatus and food intake, and reduce the length of hospital stay[19]. LR plays an important role in enhanced recovery after surgery for gastrointestinal diseases and has been gradually performed in clinical practice, resulting in improved clinical outcomes[20]. LR can cause less stress and decrease the inflammatory response, which may reduce postoperative complications[21]. In one study involving distal gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy for the treatment of gastric cancer, LR and OR were similar in terms of postoperative complications and mortality as well as the severity of complications[19]. In another study of total gastrectomy, LR reduced postoperative infectious complications[22]. Moreover, LR reportedly increased the survival time of patients with colorectal cancer undergoing elective surgery[23].

Surgeons have attempted to apply laparoscopic techniques to gGISTs because of the above-mentioned advantages. Some studies have proven the positive effects of LR in improved perioperative outcomes in patients with gGISTs[24]. Regardless of whether the gGIST is small[25] or large[26], LR can enhance the recovery of intestinal motility, promote early flatus and food intake, and reduce length of hospital stay; these benefits were also proven in the present study. These advantages are mainly associated with less trauma, milder stress, and less pain. OR usually requires larger incisions and tense sutures, which cause severe pain after surgery and often postpones early ambulation, necessitates analgesic drugs, prolongs the recovery of intestinal mobility, and lengthens the hospital stay[27].

Our study also confirmed that LR is superior to OR in terms of operative parameters. The operative time of LR was shorter than that of OR, which may have been due to the time-consuming procedures involved in opening and closing the abdomen in OR[27]. The time-saving advantages of LR are more obvious when treating gGISTs with a better location or smaller size. The lower blood loss volume in LR may provide benefits with respect to an enlarged visual field, enlarged small vessels, fine anatomic dissection, and better laparoscopic hemostasis[28]. The decreases in the operative time and intraoperative blood loss will be more obvious with the development of laparoscopic instruments and improvement in surgeons’ skills.

Although LR of gGISTs can enhance recovery after surgery, surgeons tend to be more cautious regarding its safety and effects on the long-term oncological prognosis. Once a GIST has ruptured during the operation, the recurrence rate is close to 100%; this limits the use of laparoscopy[29]. Large tumors become more adherent to the surrounding tissues, which makes laparoscopic procedures difficult and risky. The recent NCCN guideline on GISTs revised the restrictions on the maximum diameter of GISTs when performing LR and suggested that the diameter of the GIST should be < 5 cm. Experienced centers and surgeons are recommended to consider application of laparoscopic techniques in the treatment of GISTs[30].

Our center has accumulated experience in LR of both small and large gGISTs, and no intraoperative rupture has occurred to date. No significant difference in postoperative complications was observed between the LR and OR groups in the present study, which is consistent with the findings of other studies[31,32]. Some other studies have shown that LR of gGISTs may reduce postoperative complications[33]. The Clavien-Dindo classification is a commonly used evaluation system for postoperative complications[17]. Chen et al[34] found that fewer grade 1 to 3 postoperative complications occurred in LR than in OR of gGISTs, but no difference in grade 3 to 4 postoperative complications was found. Most grade 1 complications have no clinical importance, and the assessments differ according to the clinicians’ experience and preference[17]; thus, we analyzed only grade ≥ 2 complications. The classification criteria for postoperative complications vary among different centers and clinicians, which may explain the different results among previously published studies.

We also included a certain number of gGISTs with a diameter of > 5 cm, and the maximum diameter in the LR group was 14 cm. Most of the tumors were present outside of the stomach cavity. The basal part of the tumor in the stomach wall was relatively small, and the main body protruded from the serosa. The tumor was slightly adherent to the surrounding organs without invasion. With careful and precise dissection, a laparoscopic technique was successfully applied to divide the tumor and keep the pseudocapsule intact. Therefore, we suggest that a large tumor size is not an absolute contraindication for LR and that individualized evaluation is necessary in each case. Whether LR is a suitable choice depends on the results of a comprehensive evaluation including tumor location, growth features, and the relationship with the surrounding tissues. LR is safe and feasible for gGISTs in selected cases. Moreover, laparoscopic experience is necessary, just as other guidelines have suggested. OR or conversion to OR during LR may still be required despite the advantages of LR. In the present study, we excluded some very large tumors to balance the two groups; one of these tumors was 29 cm. OR may be more appropriate for these rare gGISTs. Moreover, a large abdominal incision is usually needed to remove such a large tumor.

The influence of LR and OR on the long-term prognosis of patients with gGISTs is a concern of clinicians, but the literature provides conflicting data on this topic. Most studies have shown no significant differences in postoperative recurrence and the survival time between LR and OR[35]. Some other studies have obtained different results. A European multicenter study of 61 centers involving 1413 patients with gGISTs revealed that the 5-year DFS rate in the LR group was significantly higher than that in the OR group[33]. In another meta-analysis, the recurrence rate in the OR group was significantly higher than that in the LR group. However, careful analysis of the data revealed selection bias between the two groups. Tumor size and risk stratification as two prognostic factors closely correlated with recurrence were unbalanced between the two groups. Once matched, the recurrence rate in the OR group was not higher than that in the LR group[28].

Most results to date were derived from retrospective studies, which may have different conclusions because of confounding factors or selection bias. After matching for the main potential confounders in our study, we found no significant difference in DFS or OS between the two groups; this is consistent with other reports[35]. With a better understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of GISTs and the application of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, the prognosis of patients with GISTs has been greatly improved[2]. Some studies have shown 5-year DFS rates of > 90% after adjuvant therapy[33,36]. Recent studies have found that the main prognostic factors of GISTs are the pathological features, including tumor size, mitotic count, tumor location, and intraoperative rupture[10]. The potential influence of LR and OR on these prognostic factors mainly depends on whether the incidence of intraoperative rupture increases in association with different approaches. As previously confirmed, with a carefully performed operation and the use of a specimen bag, LR is safe and feasible and does not increase the risk of rupture in appropriately selected patients. Furthermore, postoperative complications in patients with a variety of other malignancies may lead to a poor prognosis[37]; this is associated with the negative effects of postoperative complications on the initiation of subsequent anti-tumor therapy[38]. However, our study has proven that LR does not increase the incidence of postoperative complications in patients with gGISTs, and even in other studies, LR reduced the postoperative complications[33]. Notably, GISTs differ from other malignant tumors derived from epithelial cells in that R0 resection without lymphadenectomy fulfils the principle of radical resection of GISTs. For patients with epithelial malignant tumors, clinicians are often concerned about whether LR can achieve dissection of a sufficient range and number of lymph nodes as in OR[21] because this factor is closely associated with the prognosis of patients with such tumors[39].

There are some limitations in our study. Like all retrospective studies, selection bias may have been present. Although we used PSM to balance the baseline data between the two groups, some patients were eliminated and the generality of all patients with gGISTs may have been affected. For example, we excluded some patients with large tumors in the OR group, but OR may be more suitable for these tumors. Moreover, when we chose the covariates for PSM, some other factors that we did not consider may have still been present. PSM is used only for observable covariates, and some unknown confounding factors may still have an impact on the results. Therefore, prospective randomized controlled trials would be meaningful and are expected.

Surgical treatment is the gold standard for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors (gGISTs). Increasingly more surgeons are performing laparoscopic resection (LR) instead of open resection (OR) to treat gGISTs due to the development and superiority of laparoscopic technology. The efficacy and safety of LR remain unconfirmed and more high-level clinical evidence is required. Propensity score matching (PSM) is widely used to reduce selection bias caused by potential confounders in retrospective studies. The aim of this study was to retrospectively compare the short- and long-term outcomes of LR vs OR of gGISTs using PSM to adjust for confounding variables in the baseline data.

This study was based on the experience of laparoscopic surgery for gGISTs in a large single center. The authors extracted the research data from their database which has been prospectively maintained for more than ten years, and retrospectively compared the two approaches using PSM to reduce selection bias caused by potential confounders.

Laparoscopic surgery for gGISTs is superior to open surgery with respect to intraoperative parameters and postoperative recovery outcomes without compromising long-term oncological outcomes.

A large tumor size is not an absolute contraindication for LR of gGISTs. LR is safe and feasible for gGISTs in selected cases after a comprehensive evaluation including tumor location, growth features, and the relationship with the surrounding tissues.

GISTs are the most common mesenchymal neoplasms of the alimentary system and exhibit high resistance to conventional chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Surgical resection is still the mainstay and most effective treatment for GISTs to date. GISTs only require the achievement of R0 resection while lymphadenectomy is not necessary. PSM is a useful statistical method which is widely used in nonrandomized controlled clinical trials, epidemiological studies, and most observational studies to reduce selection bias caused by potential confounders and ensure that the baseline data are balanced.

GISTs are most common problems in medical practice. An adequate number of patients was enrolled in this study for a conclusion about GISTs. The study was well designed and the article was well written.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Dinc T S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Ma JY E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Rubin BP, Heinrich MC, Corless CL. Gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Lancet. 2007;369:1731-1741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 440] [Cited by in RCA: 441] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Iorio N, Sawaya RA, Friedenberg FK. Review article: the biology, diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:1376-1386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schwameis K, Fochtmann A, Schwameis M, Asari R, Schur S, Köstler W, Birner P, Ba-Ssalamah A, Zacherl J, Wrba F. Surgical treatment of GIST--an institutional experience of a high-volume center. Int J Surg. 2013;11:801-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Poveda A, del Muro XG, López-Guerrero JA, Martínez V, Romero I, Valverde C, Cubedo R, Martín-Broto J. GEIS 2013 guidelines for gastrointestinal sarcomas (GIST). Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74:883-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Søreide K, Sandvik OM, Søreide JA, Giljaca V, Jureckova A, Bulusu VR. Global epidemiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST): A systematic review of population-based cohort studies. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;40:39-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 579] [Cited by in RCA: 520] [Article Influence: 57.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Kawanowa K, Sakuma Y, Sakurai S, Hishima T, Iwasaki Y, Saito K, Hosoya Y, Nakajima T, Funata N. High incidence of microscopic gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1527-1535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Correa-Cote J, Morales-Uribe C, Sanabria A. Laparoscopic management of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:296-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lukaszczyk JJ, Preletz RJ Jr. Laparoscopic resection of benign stromal tumor of the stomach. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1992;2:331-334. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Riihimäki J, Nishida T, Steigen SE, Brabec P, Plank L, Nilsson B, Cirilli C, Braconi C. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:265-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 576] [Cited by in RCA: 671] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nishida T, Blay JY, Hirota S, Kitagawa Y, Kang YK. The standard diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of gastrointestinal stromal tumors based on guidelines. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:3-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 323] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Poveda A, Martinez V, Serrano C, Sevilla I, Lecumberri MJ, de Beveridge RD, Estival A, Vicente D, Rubió J, Martin-Broto J. SEOM Clinical Guideline for gastrointestinal sarcomas (GIST) (2016). Clin Transl Oncol. 2016;18:1221-1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | von Mehren M, Randall RL, Benjamin RS, Boles S, Bui MM, Conrad EU 3rd, Ganjoo KN, George S, Gonzalez RJ, Heslin MJ, Kane JM 3rd, Koon H, Mayerson J, McCarter M, McGarry SV, Meyer C, O’Donnell RJ, Pappo AS, Paz IB, Petersen IA, Pfeifer JD, Riedel RF, Schuetze S, Schupak KD, Schwartz HS, Tap WD, Wayne JD, Bergman MA, Scavone J. Soft Tissue Sarcoma, Version 2.2016, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:758-786. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Demetri GD, Benjamin RS, Blanke CD, Blay JY, Casali P, Choi H, Corless CL, Debiec-Rychter M, DeMatteo RP, Ettinger DS. NCCN Task Force report: management of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST)--update of the NCCN clinical practice guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5 Suppl 2:S1-29; quiz S30. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Reichardt P, Blay JY, Mehren Mv. Towards global consensus in the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2010;10:221-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pelletier JS, Gill RS, Gazala S, Karmali S. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Open vs. Laparoscopic Resection of Gastric Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. J Clin Med Res. 2015;7:289-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Deb S, Austin PC, Tu JV, Ko DT, Mazer CD, Kiss A, Fremes SE. A Review of Propensity-Score Methods and Their Use in Cardiovascular Research. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:259-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1411-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 699] [Cited by in RCA: 865] [Article Influence: 50.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hu Y, Huang C, Sun Y, Su X, Cao H, Hu J, Xue Y, Suo J, Tao K, He X. Morbidity and Mortality of Laparoscopic Versus Open D2 Distal Gastrectomy for Advanced Gastric Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1350-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 536] [Cited by in RCA: 530] [Article Influence: 58.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Abdikarim I, Cao XY, Li SZ, Zhao YQ, Taupyk Y, Wang Q. Enhanced recovery after surgery with laparoscopic radical gastrectomy for stomach carcinomas. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:13339-13344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Caruso S, Patriti A, Roviello F, De Franco L, Franceschini F, Coratti A, Ceccarelli G. Laparoscopic and robot-assisted gastrectomy for gastric cancer: Current considerations. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:5694-5717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Inokuchi M, Otsuki S, Ogawa N, Tanioka T, Okuno K, Gokita K, Kawano T, Kojima K. Postoperative Complications of Laparoscopic Total Gastrectomy versus Open Total Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer in a Meta-Analysis of High-Quality Case-Controlled Studies. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:2617903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Askari A, Nachiappan S, Currie A, Bottle A, Athanasiou T, Faiz O. Selection for laparoscopic resection confers a survival benefit in colorectal cancer surgery in England. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:3839-3847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hu J, Or BH, Hu K, Wang ML. Comparison of the post-operative outcomes and survival of laparoscopic versus open resections for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A multi-center prospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2016;33 Pt A:65-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Goh BK, Chow PK, Chok AY, Chan WH, Chung YF, Ong HS, Wong WK. Impact of the introduction of laparoscopic wedge resection as a surgical option for suspected small/medium-sized gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach on perioperative and oncologic outcomes. World J Surg. 2010;34:1847-1852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lin J, Huang C, Zheng C, Li P, Xie J, Wang J, Lu J. Laparoscopic versus open gastric resection for larger than 5 cm primary gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): a size-matched comparison. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2577-2583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chen QL, Pan Y, Cai JQ, Wu D, Chen K, Mou YP. Laparoscopic versus open resection for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chen K, Zhou YC, Mou YP, Xu XW, Jin WW, Ajoodhea H. Systematic review and meta-analysis of safety and efficacy of laparoscopic resection for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:355-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hohenberger P, Ronellenfitsch U, Oladeji O, Pink D, Ströbel P, Wardelmann E, Reichardt P. Pattern of recurrence in patients with ruptured primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1854-1859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | von Mehren M, Randall RL, Benjamin RS, Boles S, Bui MM, Casper ES, Conrad EU 3rd, DeLaney TF, Ganjoo KN, George S, Gonzalez RJ, Heslin MJ, Kane JM 3rd, Mayerson J, McGarry SV, Meyer C, O’Donnell RJ, Pappo AS, Paz IB, Pfeifer JD, Riedel RF, Schuetze S, Schupak KD, Schwartz HS, Van Tine BA, Wayne JD, Bergman MA, Sundar H. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors, version 2.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:853-862. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Cai JQ, Chen K, Mou YP, Pan Y, Xu XW, Zhou YC, Huang CJ. Laparoscopic versus open wedge resection for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a single-center 8-year retrospective cohort study of 156 patients with long-term follow-up. BMC Surg. 2015;15:58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Goh BK, Goh YC, Eng AK, Chan WH, Chow PK, Chung YF, Ong HS, Wong WK. Outcome after laparoscopic versus open wedge resection for suspected gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A matched-pair case-control study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:905-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Piessen G, Lefèvre JH, Cabau M, Duhamel A, Behal H, Perniceni T, Mabrut JY, Regimbeau JM, Bonvalot S, Tiberio GA. Laparoscopic Versus Open Surgery for Gastric Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: What Is the Impact on Postoperative Outcome and Oncologic Results? Ann Surg. 2015;262:831-839; discussion 829-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chen QF, Huang CM, Lin M, Lin JX, Lu J, Zheng CH, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB, Chen QY. Short- and Long-Term Outcomes of Laparoscopic Versus Open Resection for Gastric Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: A Propensity Score-Matching Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Koh YX, Chok AY, Zheng HL, Tan CS, Chow PK, Wong WK, Goh BK. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing laparoscopic versus open gastric resections for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:3549-3560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Xu C, Chen T, Hu Y, Balde AI, Liu H, Yu J, Zhen L, Li G. Retrospective study of laparoscopic versus open gastric resection for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors based on the propensity score matching method. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:374-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kulu Y, Tarantio I, Warschkow R, Kny S, Schneider M, Schmied BM, Büchler MW, Ulrich A. Anastomotic leakage is associated with impaired overall and disease-free survival after curative rectal cancer resection: a propensity score analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:2059-2067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | A T M Abdul K, Murakami Y, Yoshimoto M, Onishi K, Kuroda H, Matsunaga T, Fukumoto Y, Takano S, Tokuyasu N, Osaki T. Intra-Abdominal Complications after Curative Gastrectomies Worsen Prognoses of Patients with Stage II-III Gastric Cancer. Yonago Acta Med. 2016;59:210-216. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Wu CW, Hsiung CA, Lo SS, Hsieh MC, Chen JH, Li AF, Lui WY, Whang-Peng J. Nodal dissection for patients with gastric cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:309-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 472] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |