Published online Jun 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i24.4467

Peer-review started: March 19, 2017

First decision: April 11, 2017

Revised: April 26, 2017

Accepted: June 1, 2017

Article in press: June 1, 2017

Published online: June 28, 2017

Processing time: 100 Days and 0.2 Hours

Primary pancreatic lymphoma (PPL) is an extremely rare form of extranodal malignant lymphoma. The most common histological subtype of PPL is diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL). In rare cases, PPL can also present as follicular lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, and T cell lymphoma either of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma or of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (T/HRBCL) is an uncommon morphologic variant of DLBCL with aggressive clinical course, it is predominantly a nodal disease, but extranodal sites such as bone marrow, liver, and spleen can be involved. Pancreatic involvement of T/HRBCL was not presented before. Herein, we report a 48-year-old male who was hospitalized with complaints of jaundice, dark brown urine, pale stools, and nausea. The radiological evaluation revealed a pancreatic head mass and, following operative biopsy, the tumor was diagnosed as T/HRBCL. The patient achieved remission after six cycles of CHOP chemotherapy. Therefore, T/HRBCL can be treated similarly to the stage-matched DLBCL and both of them get equivalent outcomes after chemotherapy.

Core tip: T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (T/HRBCL) is an uncommon morphologic variant of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Pancreatic T/HRBCL has not been reported to date. Here, we present the first case of a patient diagnosed with pancreatic T/HRBCL who was successfully treated with systemic chemotherapy.

- Citation: Zheng SM, Zhou DJ, Chen YH, Jiang R, Wang YX, Zhang Y, Xue HL, Wang HQ, Mou D, Zeng WZ. Pancreatic T/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(24): 4467-4472

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i24/4467.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i24.4467

Two main types of lymphoma have been described to date, namely lymphoma (HL) and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). HLs are nodular lesions that rarely disseminate to the extralymphatic organs, while NHLs often invade extralymphatic organs and do not spread in a contiguous fashion. The primary sites most frequently affected are head-neck area and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (in ascending order). At the level of the oral cavity, the most affected sites are tonsils (55% of oral cases), palate (30% of cases), and genial mucosa (2% of cases). There are, instead, sporadic manifestations affecting the tongue (2% of cases), the buccal floor (2% of cases), and the retromolar trigone (2% of cases)[1]. In Western series, GI lymphoma occurs principally in the stomach, followed by the small bowel and the colon[2].

Primary pancreatic lymphoma (PPL) is a rare form of extranodal malignant lymphoma. Approximately 0.1% of all malignant lymphomas, fewer than 2% of extranodal malignant lymphomas, and 0.5% of all pancreatic masses constitute PPLs[2-5]. Volmar et al[6] evaluated the pathological results of 1050 fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies of pancreatic lesions and reported that only 14 (1.3%) cases were pancreatic lymphomas. PPL represents a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge due to its rarity, difficult anatomic location to access, nonspecific clinical presentation that can mimic pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and variety of its histological subtypes. Histological subtype is a major prognostic factor in nodal and extranodal lymphomas.

The most common histological subtype of PPL is diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL). T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (T/HRBCL) is an uncommon morphologic variant of DLBCL, accounting for approximately 1% to 3% of all DLBCL[7-11]. Nearly one half of patients with T/HRBCL present with liver, bone marrow, and/or spleen involvement[12]. Pancreatic involvement of T/HRBCL has not been reported previously. We hereby present the first case of T/HRBCL arising from pancreas.

A 48-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with 1-wk history of jaundice, dark brown urine, pale stools, and nausea. His medical history and physical exam were unremarkable. Laboratory workup revealed hepatic panel in cholestatic pattern with total bilirubin of 117 μmol/L, conjugated bilirubin of 66.8 μmol/L, alkaline phosphatase of 173 IU/L, γ-Glutamyltransferase (γ-GT) of 380 IU/L, and Alanine transaminase of 468 IU/L. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) was 11783 IU/mL. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and β2-microglobulin were normal. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) with contrast revealed a 4.2 cm × 4.1 cm hypodense mass within the pancreatic head and enlargement of several mesenteric and retroperitoneal lymph nodes (Figure 1). Endoscopic retrograde cholan-giopancreatography suggested an extrinsic compression of distal common bile duct with intrahepatic biliary dilation. He was clinically diagnosed as pancreatic tumor. During the surgery, a 4 cm × 3 cm × 4 cm mass was identified within the head of the pancreas, with several enlarged lymph nodes around the head of the pancreas and in the mesentery of the small intestine. The intraoperative frozen section of pancreatic head revealed chronic inflammation with atypical cells that were concerning for nonepithelial malignancy, thus the diagnosis of malignant lymphoma was suspected. Based on these findings, diagnostic biopsy of pancreatic mass, Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy, and Billroth II gastrojejunostomy were performed.

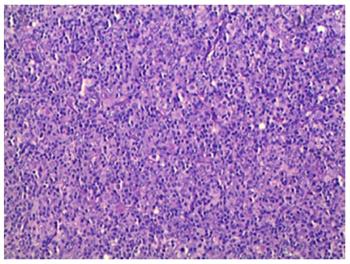

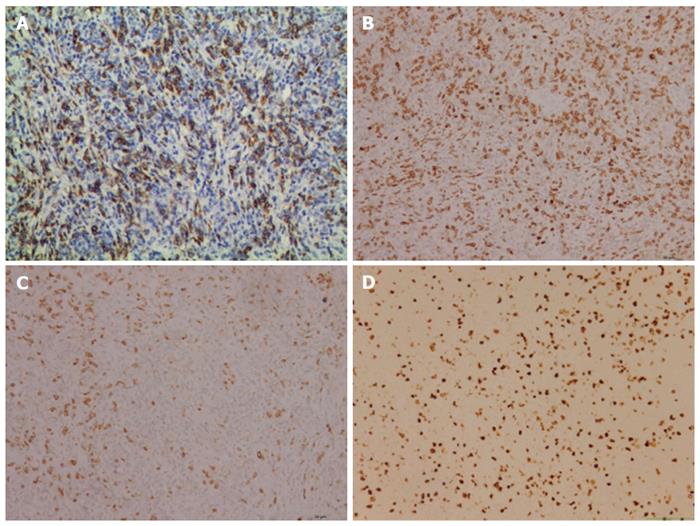

Postoperative histology of the pancreatic mass and mesenteric lymph node biopsies showed entirely effaced architecture by predominantly small lymphocytes and less often histiocytes. In addition, a limited number of scattered large atypical cells with pleomorphic vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli were embedded in the background (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical examination showed that the interspersed large atypical lymphoid cells were positive for pan-B cell markers CD20 (Figure 3A), PAX-5, CD21, CD43 and CD45RO. Most of the small lymphoid cells were CD3 positive T cells (Figure 3B). The histiocytes expressed CD68 (Figure 3C). Immunostaining for Ki-67 revealed a proliferation fraction of 30% among large atypical lymphoid cells (Figure 3D). Based on these histological features and immunophenotype, a diagnosis of pancreatic T/HRBCL was established.

One month after the operation, the patient was treated with 4 cycles of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, oncovin, adriamycin, and prednisone) regimen. He had significant improvement in radiological findings at the end of the 4th cycle. Two more CHOP regimens were completed to totally 6 cycles. A repeated CT scan one month after the last CHOP chemotherapy showed a complete remission. The patient was eventful and had no signs of recurrence in the 5 years since the last chemotherapy.

PPL, a lymphoma localized to the pancreas with or without peripancreatic nodal involvement, is an exceedingly rare entity. Two main criteria have been used to define PPL[13,14]. However, there is now a standardized definition within the current World Health Organization framework of primary extranodal lymphomas, which facilitates uniformity and precision[15]. PPL is generally defined when the bulk of the disease is localized to the pancreas. Adjacent lymph node involvement and distant spread may exist but the primary clinical presentation is in the pancreas and therapy is targeted to this location. Our case demonstrates all the above criteria.

The most common histological subtype of PPL is DLBCL, accounting for 77% to 80% of all patients[3,16,17]. PPL can also present as follicular lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma, and T cell lymphoma[17-19]. T/HRBCL is a nodal disease, but extralnodal sites, such as spleen, liver and bone marrow can be involved[10-12,20,21]. In recent reports, primary cutaneous[22], thyroid[23], thymus[24], and gastrointestinal presentations[25,26] of T/HRBCL were also described. To date, pancreatic involvement of T/HRBCL has not been reported.

T/HRBCL is an uncommon morphological variant of DLBCL, but one with many distinctive clinical features[7,8]. T/HRBCL tends to present in a relatively younger age group with a median age in the fourth decade and demonstrates male predominance, while DLBCL usually occurs in the fifth or sixth decade of life. T/HRBCL mostly presents in more advanced stages and has an aggressive clinical course[11,20]. It is crucial to differentiate PPL including T/HRBCL from those of occupying lesions, such as pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and inflammatory ones, including acute or chronic pancreatitis, autoimmune diseases, or pancreatic tuberculosis, since their treatment and prognosis may differ considerably. Both pancreatic adenocarcinoma and PPL are diagnosed at a similar age and can present with nonspecific clinical presentations and radiographic findings. Percutaneous ultrasound, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), CT, and magnetic resonance imaging are well-established procedures to evaluate pancreatic lesions. Two different morphological patterns of pancreatic involvement are observed, namely a localized, well-circumscribed tumor pattern, as in the present case, and a diffuse enlargement pattern, infiltrating or replacing the majority of the pancreatic gland[27]. The combination of a bulky head of pancreas tumor without dilatation of main pancreatic duct and with significant lymphadenopathy below the level of renal veins points to the diagnosis of PPL, while the presence of calcification or necrosis rules out lymphoma. Positron emission tomography scan is generally helpful in the staging of lymphoma, particularly in differentiating malignant lesion from benign ones. Although imaging techniques may suggest PPL, they are unable to distinguish between PPL and other pancreatic lesions. Therefore, the definitive diagnosis of PPL is based on the histopathological and cytopathological examinations. For a definitive diagnosis, CT-, or EUS-guided FNA biopsy is the optimal approach, as it is highly accurate. Alternatively, a laparoscopy or laparotomy may be performed to conduct a biopsy of the pancreatic mass or lymph nodes when the FNA biopsy is nondiagnostic or inadequate. In addition, submitting the specimen to flow cytometry is a valuable method for the diagnosis of PPL to individualize the appropriate therapy[27]. The laboratory tests are nonspecific for PPL. Sadot et al[17] reported that serum LDH level was elevated in 55% of the PPL cases, while CA19-9 was increased in 25% of PPL patients. In our case, the serum CA19-9 level was significantly increased, but his LDH and beta;2-microglobulin levels were normal.

Due to its rarity, nonspecific clinical manifestations, and variety of histological subtypes, final diagnosis and classification of PPL subtypes are often very difficult tasks without the aid of a cytopathological and immunopathological evaluation. The cells in T/HRBCL have a wide cytological spectrum characterized by fewer than 10% large neoplastic B cells (CD20, CD21, PAX-5, CD43 or CD45RO positive) amid a prominent inflammatory infiltrates, the majority of which are small polyclonal T cells with or without the presence of histiocytes. Despite a rich T cell background, well-formed T cell rosettes are usually absent in T/HRBCL. T/HRBCL shares several morphologic and immunophenotypic similarities with nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NLPHL), posing a great diagnostic challenge in some cases[28]. The histological distinction between T/HRBCL and NLPHL largely relies on immunohistochemical analysis of the background population. Features that favor T/HRBCL usually include the absence of background small B cells. NLPHL shows nodules containing numerous small lymphocytes and a variable number of variant Hodgkin’s cells (popcorn cells) which are usually positive for CD45 and CD20 but negative for CD15 and CD30. However, the surrounding small lymphocytes in NLPHL are usually a mixture of B cells (predominately) and T cells (though rich T cells can be seen in late stage of NLPHL), and CD57 or PD-1 positive T cells rosette around the large neoplastic B cells[29]. In the present case, the small lymphocytes in the background were predominantly CD3 positive T cells with no T cell rosettes, suggesting a T/HRBCL.

Regarding treatment, T/HRBCL patients are generally treated similarly to the stage-matched DLBCL[30]. When patients are well matched according to the IPI and the treatment is adapted to the disease stage and risk, T/HRBCL and conventional DLBCL have similar outcomes after chemotherapy[11]. Anthracycline-based CHOP regimen is recommended as the standard treatment for T/HRBCL. A series of early studies related to the treatment of T/HRBCL demonstrated that the complete response (CR) rate of T/HRBCL to chemotherapy was 48% to 85%, and the 3-year and 5-year overall survival (OS) rate were 50% to 64% and 46% to 58%, respectively[11,30,31]. The matched-control analysis showed a trend toward a better response to chemotherapy for patients with DLBCL than T/HRBCL, whereas no difference was observed in OS between the two groups[11]. Recently, CHOP chemotherapy in combination with rituximab (R-CHOP) is used in T/HRBCL as it is used in all CD20 positive nodal and extranodal lymphomas[11,32]. Kim et al[33] reported that there was no significant difference in the CR rate to R-CHOP between T/HRBCL (91%) and DLBCL (97%). The 3-year OS rates were 75% for T/HRBCL and 81% for DLBCL, respectively (P = 0.719). The addition of rituximab to CHOP seems to be helpful for the management of T/HRBCL, as it is for DLBCL. Chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy may be useful for the treatment. Behrns et al[13] reported that the median survival time for single chemotherapy and radiotherapy-treated PPL patients was 13 and 22 mo, respectively, whereas it could be improved to 26 mo with combined chemoradiotherapy. The role of surgery should be reserved for diagnostic or palliative intent. Lin et al[3] reported that patients with biliary tract or gastrointestinal obstruction should receive biliary or gastric bypass. After surgery, the systemic chemotherapy should be initiated for long-term remission. It is, therefore, important to choose the appropriate treatment depending on disease progression and condition of patients. In our case, the patient was not diagnosed with PPL preoperatively, and there was obstruction of the biliary tract, so gastrointestinal and biliary bypass was performed to alleviate symptoms for subsequent therapy. The present case showed a good clinical course; however, prolonged follow-up is recommended to monitor disease relapse at both the primary and distant sites.

Although patients with malignant lymphoma benefit from the traditional treatments, the prognosis of the entity is poor due to the high relapse of the disease and the toxicity of these therapies. Besides the present chemotharepy, developing safer agents is an important project. A recent study described that the antioxidant and antitumor activity of the bioactive polyphenolic fraction isolated from the beer brewing process may be helpful for antitumor therapy, which throws a new light on treatment of lymphomas[34].

In summary, pancreatic H/TRBCL is an aggressive disease that often presents with adverse prognostic factors. However, when treatment is adapted to the disease risk, outcome is equivalent to patients with DLBCL. Systemic chemotherapy should be the initial therapy when the diagnosis is established. Chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy may be useful for the treatment. Surgery should be reserved for diagnostic and non-curative intent. Prolonged follow-up is recommended to detect relapse. Further innovative researches on antitumor therapies should be undertaken to make new possibilities for improvement of the poor prognosis of malignant lymphoma.

A 48-year-old man was referred to our hospital with 1-wk history of jaundice, dark brown urine, pale stools, and nausea.

A 4-cm-diameter mass located in the pancreatic head, along with enlarged mesenteric and retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, chronic pancreatitis, peripheral T cell lymphoma, or nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

The abdominal computed tomography scan showed a 4-cm-diameter tumor located in the pancreatic head and enlargement of several mesenteric and retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

Laboratory workup revealed hepatic panel in cholestatic pattern with total bilirubin of 117 μmol/L, conjugated bilirubin of 66.8 μmol/L, alkaline phosphatase of 173 IU/L, and γ-Glutamyltransferase of 380 IU/L. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 is 11783 IU/mL.

Primary pancreatic T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (T/HRBCL).

Surgical bypass followed by systemic chemotherapy was performed.

Previously, cases of primary cutaneous, thyroid, thymus, and gastrointestinal T/HRBCL were reported.

Primary pancreatic lymphoma (PPL), a lymphoma localized to the pancreas with or without peripancreatic nodal involvement, is an exceedingly rare entity. The most common histological subtype of PPL is diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Pancreatic T/HRBCL is an uncommon morphologic variant of DLBCL arising from pancreas.

Systemic therapy should be the initial therapy when the diagnosis of primary pancreatic T/HRBCL is established. Surgery should be reserved for diagnostic and non-curative intent. Prolonged follow-up is recommended to detect relapse.

Authors reported the first case of a patient diagnosed with pancreatic T/HRBCL who was successfully treated with systemic chemotherapy. Novelty of the case is that lymphoma in pancreas otherwise diagnosis and management are same.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Alberti LR, Tatullo M, Kute VB S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Inchingolo F, Tatullo M, Abenavoli FM, Marrelli M, Inchingolo AD, Inchingolo AM, Dipalma G. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma affecting the tongue: unusual intra-oral location. Head Neck Oncol. 2011;3:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zucca E, Roggero E, Bertoni F, Cavalli F. Primary extranodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Part 1: Gastrointestinal, cutaneous and genitourinary lymphomas. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:727-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lin H, Li SD, Hu XG, Li ZS. Primary pancreatic lymphoma: report of six cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5064-5067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Haji AG, Sharma S, Majeed KA, Vijaykumar DK, Pavithran K, Dinesh M. Primary pancreatic lymphoma: Report of three cases with review of literature. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2009;30:20-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Volmar KE, Routbort MJ, Jones CK, Xie HB. Primary pancreatic lymphoma evaluated by fine-needle aspiration: findings in 14 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:898-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pittaluga S, Jaffe ES. T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica. 2010;95:352-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Abramson JS. T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma: biology, diagnosis, and management. Oncologist. 2006;11:384-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang GB, Xu GL, Luo GY, Shan HB, Li Y, Gao XY, Li JJ, Zhang R. Primary intestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 81 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4625-4631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fraga M, Sánchez-Verde L, Forteza J, García-Rivero A, Piris MA. T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma is a disseminated aggressive neoplasm: differential diagnosis from Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Histopathology. 2002;41:216-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bouabdallah R, Mounier N, Guettier C, Molina T, Ribrag V, Thieblemont C, Sonet A, Delmer A, Belhadj K, Gaulard P. T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphomas and classical diffuse large B-cell lymphomas have similar outcome after chemotherapy: a matched-control analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1271-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fan Z, Natkunam Y, Bair E, Tibshirani R, Warnke RA. Characterization of variant patterns of nodular lymphocyte predominant hodgkin lymphoma with immunohistologic and clinical correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1346-1356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Behrns KE, Sarr MG, Strickler JG. Pancreatic lymphoma: is it a surgical disease? Pancreas. 1994;9:662-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dawson IM, Cornes JS, Morson BC. Primary malignant lymphoid tumours of the intestinal tract. Report of 37 cases with a study of factors influencing prognosis. Br J Surg. 1961;49:80-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 525] [Cited by in RCA: 469] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA, editors . Pathology and genetics of tumours of the digestive system. World Health Organization classification of tumours. IARC Press: Lyon 2000; 250 Available from: http://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/pat-gen/bb2/BB2.pdf. |

| 16. | Alexander RE, Nakeeb A, Sandrasegaran K, Robertson MJ, An C, Al-Haddad MA, Chen JH. Primary pancreatic follicle center-derived lymphoma masquerading as carcinoma. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011;7:834-838. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Sadot E, Yahalom J, Do RK, Teruya-Feldstein J, Allen PJ, Gönen M, D’Angelica MI, Kingham TP, Jarnagin WR, DeMatteo RP. Clinical features and outcome of primary pancreatic lymphoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1176-1184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nasher O, Hall NJ, Sebire NJ, de Coppi P, Pierro A. Pancreatic tumours in children: diagnosis, treatment and outcome. Pediatr Surg Int. 2015;31:831-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bhagat VH, Sepe T. Pancreatic lymphoma complicating early stage chronic hepatitis C. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:pii: bcr2016216698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Greer JP, Macon WR, Lamar RE, Wolff SN, Stein RS, Flexner JM, Collins RD, Cousar JB. T-cell-rich B-cell lymphomas: diagnosis and response to therapy of 44 patients. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1742-1750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dominis M, Dzebro S, Gasparov S, Pesut A, Kusec R. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and its variants. Croat Med J. 2002;43:535-540. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Vezzoli P, Fiorani R, Girgenti V, Fanoni D, Tavecchio S, Balice Y, Mozzana R, Crosti C, Berti E. Cutaneous T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;222:225-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ichikawa S, Watanabe Y, Saito K, Kimura J, Ichinohasama R, Harigae H. T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma of the thyroid. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2013;2:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Xu J, Wu X, Reddy V. T Cell/Histiocyte-Rich Large B Cell Lymphoma of the Thymus: A Diagnostic Pitfall. Case Rep Hematol. 2016;2016:2942594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Barut F, Kandemir NO, Gun BD, Ozdamar SO. T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma of stomach. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66:905-907. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Köksal AR, Alkim H, Ergun M, Boga S, Bayram M, Alkim C, Eryilmaz OT. First case of T-cell/histiocyte-rich-large B-cell lymphoma presenting with duodenal obstruction. Libyan J Med. 2013;8:22955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Merkle EM, Bender GN, Brambs HJ. Imaging findings in pancreatic lymphoma: differential aspects. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:671-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Xie Y, Pittaluga S, Jaffe ES. The histological classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Semin Hematol. 2015;52:57-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nam-Cha SH, Roncador G, Sanchez-Verde L, Montes-Moreno S, Acevedo A, Domínguez-Franjo P, Piris MA. PD-1, a follicular T-cell marker useful for recognizing nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1252-1257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | El Weshi A, Akhtar S, Mourad WA, Ajarim D, Abdelsalm M, Khafaga Y, Bazarbashi S, Maghfoor I. T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma: Clinical presentation, management and prognostic factors: report on 61 patients and review of literature. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:1764-1773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Aki H, Tuzuner N, Ongoren S, Baslar Z, Soysal T, Ferhanoglu B, Sahinler I, Aydin Y, Ulku B, Aktuglu G. T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 21 cases and comparison with 43 cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Res. 2004;28:229-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Valera ET, Queiroz RG, Brassesco MS, Scrideli CA, Neves F, Tone LG. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy and minimal residual disease status of T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:348-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kim YS, Ji JH, Ko YH, Kim SJ, Kim WS. Matched-pair analysis comparing the outcomes of T cell/histiocyte-rich large B cell lymphoma and diffuse large B cell lymphoma in patients treated with rituximab-CHOP. Acta Haematol. 2014;131:156-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Tatullo M, Simone GM, Tarullo F, Irlandese G, Vito D, Marrelli M, Santacroce L, Cocco T, Ballini A, Scacco S. Antioxidant and Antitumor Activity of a Bioactive Polyphenolic Fraction Isolated from the Brewing Process. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |