Published online Jun 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i24.4454

Peer-review started: December 30, 2016

First decision: February 9, 2017

Revised: March 1, 2017

Accepted: March 30, 2017

Article in press: March 30, 2017

Published online: June 28, 2017

Processing time: 179 Days and 12.5 Hours

To compare the tolerability and quality of bowel cleansing between 2 L polyethylene glycol (PEG) and reduced-dose sodium phosphate (NaP) tablets as a preparation for colonoscopy.

Two hundred patients were randomly assigned to the PEG or NaP groups at the same ratio. The NaP group patients took 30 tablets with 2 L of clear liquid, while the PEG group patients took 2L of PEG. Tolerability was assessed by a questionnaire about taste, volume, and the overall impression. The bowel cleansing quality was evaluated by colonoscopists.

Although NaP showed better tolerability in terms of taste, volume and overall impression (P < 0.01, P < 0.01 and P = 0.02, respectively), the overall cleansing quality was better in the PEG group (P < 0.01). A subgroup analysis, stratified by sex and age, indicated that NaP was associated with better tolerability and equivalent bowel cleansing quality in females of < 50 years of age.

Despite the better tolerability, the use of 30 NaP tablets with 2 L of clear liquid should be limited due to its lower cleansing quality; however, in certain cases the regimen may deserve consideration, particularly in cases involving young women.

Core tip: Colonoscopy is indispensable for the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal diseases. However, colonoscopy inevitably requires bowel preparation, which is sometimes burdensome to patients. We conducted a randomized clinical trial of the bowel preparation to seek the better tolerability and quality. We compared 2 L polyethylene glycol (PEG) and 30 sodium phosphate (NaP) tablets. Total 200 patients were randomly assigned to each group. We found that the cleansing quality was better in the PEG group, and NaP showed better tolerability. Especially in females of < 50 years of age, NaP was associated with better tolerability and equivalent bowel cleansing quality.

- Citation: Ako S, Takemoto K, Yasutomi E, Sakaguchi C, Murakami M, Sunami T, Oka S, Kenta H, Okazaki N, Baba Y, Yamasaki Y, Asato T, Kawai D, Takenaka R, Tsugeno H, Hiraoka S, Kato J, Fujiki S. Comparing reduced-dose sodium phosphate tablets to 2 L of polyethylene glycol: A randomized study. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(24): 4454-4461

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i24/4454.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i24.4454

Colonoscopy is necessary for the diagnosis of colorectal cancer (CRC) and for the diagnosis and treatment of its precancerous lesions. The guidelines of the American Gastroenterological Association recommend that adults of ≥ 50 years of age should undergo colonoscopy every 10 years for the early detection of CRC[1].

Colonoscopy inevitably requires bowel preparation, which is sometimes burdensome to patients. At almost all institutions in Japan, electrolyte solutions containing polyethylene glycol (PEG) are used as a purgative for preparation. The agent is an isotonic and non-absorbable solution. In Japan, the intake of 2 L of PEG is usually recommended for preparation. However, this amount is sometimes insufficient and a greater volume is required for some patients[2,3]. Another problem associated with the solution is that its unique flavor and taste are not tolerated by some patients.

Sodium phosphate (NaP) tablets (Visiclear, Zeria Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) were commercially approved as a laxative for bowel preparation in Japan in 2007. One tablet contains sodium phosphate monobasic monohydrate (734.7 mg) and sodium phosphate dibasic anhydrous (265.3 mg) for a total of 1.0 g of sodium phosphate per tablet. NaP is an osmotic laxative, which works by drawing fluids into the intestinal canal. Patients can take NaP tablets with clear liquids such as water or tea. The recommended dose for bowel preparation is 50 tablets with 2 L of clear liquid (5 NaP tablets with 200 mL of clear liquid every 15 min).

Several reports have compared the tolerability and cleansing efficacy between PEG and NaP tablets[4-8]. One report comparing 2 L of PEG to 50 NaP tablets with 2 L of clear liquid showed no difference in the bowel cleansing quality of the two solutions. In addition, 50 NaP tablets was found to be more tolerable than 2 L of PEG[6]. Another report compared 2 L of PEG to 30 NaP tablets with 1.2 L of clear liquid, and found that the bowel cleansing achieved with the tablets was of equivalent quality to 2 L of PEG and that the tablets were more tolerable[9]. However, NaP tablets are relatively large (16.0 mm × 8.0 mm × 6.5 mm), and taking 5 tablets with 200 mL clear liquid at one time may be difficult for some patients. In this regard, it was considered that reducing the number of NaP tablets taken with the determined amount of liquid might improve the tolerability of the preparation without impairing the quality of bowel cleansing. In fact, a report compared 30 NaP tablets with 2 L of clear liquid and 50 NaP tablets with 2 L of clear liquid[10], and found no difference in the tolerability or quality of bowel cleansing achieved with these preparations.

Thus, the present study was performed to compare the bowel cleansing quality and tolerability of 30 NaP tablets with 2 L of clear liquid in comparison to 2 L of PEG.

This single-center, prospective, randomized study was conducted at Tsuyama Chuo Hospital in Japan from August 2012 to August 2013, and was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000023529). Written informed consent was obtained from all of the patients prior to enrollment.

Consecutive subjects who ranged from 20 to 64 years of age and who were scheduled for colonoscopy were invited to participate in this study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: < 20 years of age, > 64 years of age, the presence of bowel obstruction, renal failure, uncontrollable hypertension, and hypersensitivity to PEG or NaP. On the day of colonoscopy, the patients were allocated to either receive NaP or PEG as a laxative by the envelope method.

The patients of both groups were asked to drink clear liquid alone after dinner on the day before colonoscopy - other dietary restrictions were not required. They received 20 mL of 0.75% sodium picosulfate (Laxoberon; Teijin Pharma Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) at 8 p.m. on the previous night and 2 metoclopramide (10 mg) tablets (Primperan, Astellas Pharma Inc., Tokyo, Japan) on the morning of the procedure. All of the patients took bowel preparation solutions (PEG or NaP) in the preparation room of the hospital. In the PEG group, the patients were asked to drink 2 L of PEG (NIFLEC, EA Pharma Co., Ltd, Japan) within approximately 2 h on the morning of the procedure. In the NaP group, the patients were asked to take 30 NaP tablets with 2 L of water/tea (3 tablets every 10 min with 200 mL water). After finishing the requested solution, a nurse checked whether the patient’s stool had become transparent. If the stool was not sufficiently transparent to perform colonoscopy, the patients were asked to take an additional amount of the assigned solution.

After bowel preparation, the patients were placed in the left lateral decubitus position at the start of colonoscopy. Their blood pressure, pulse rate and oxygen saturation were continuously monitored during the procedure. No patients received anesthesia. Scopolamine butylbromide (10 mg; Buscopan, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Tokyo, Japan) or glucagon (1 mg) was intravenously injected to suppress intestinal spasms. The colonoscopists were blinded to the results of the preparation that the patients had received. The duration of insertion into the cecum was measured. The observation time from the cecum to the anus was also measured.

Tolerability was assessed by a questionnaire that was issued to the patients. After the completion of the purgative, a questionnaire was administered to assess the taste, volume, and overall impression of the ingested solution on a 4-grade scale (easily acceptable, relatively acceptable, relatively unacceptable, or unacceptable). The quality of bowel cleansing was evaluated by colonoscopists. After finishing the procedure, the colonoscopists assessed the effectiveness of the colon preparation in each of the following segments: the cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum. In addition, the overall status of cleanliness throughout the colorectum was evaluated. The evaluation used a 4-grade scale: good (no residual feces), fair (a small amount residual feces that could be removed via suction through the endoscope channel), poor (a moderate amount residual feces that could not be removed easily but which did not affect the accuracy of the observation) and inadequate (a large amount of residual feces that significantly affected the observation).

Subgroup analyses, stratified by sex and age (< 50 years of age and ≥ 50 years of age) were also performed to investigate the tolerability and quality of cleansing in order to identify the optimal targets for each laxative.

The sample size was calculated based on the non-inferiority of the cleansing quality of reduced NaP tablets in comparison to 2 L of PEG. We defined “good” and “fair” as successful bowel preparation, and assumed a success rate of 95% in both arms, with a 15% non-inferiority margin, α = 0.05, and β = 0.2. Thus, 84 patients were required in each group. Accordingly, we set the sample size as 100 patients per group.

All of the statistical analyses were performed using the JMP 11.0 software program (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States). The age, sex, body mass index, history of abdominal surgery, stool frequency, and indications for colonoscopy in the two groups were comparable. The χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test and Student’s t-test were used as appropriate for the statistical analyses. The Mann-Whitney test was performed to compare the insertion time and observation time between the groups. All of the P values were two tailed. P values of < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

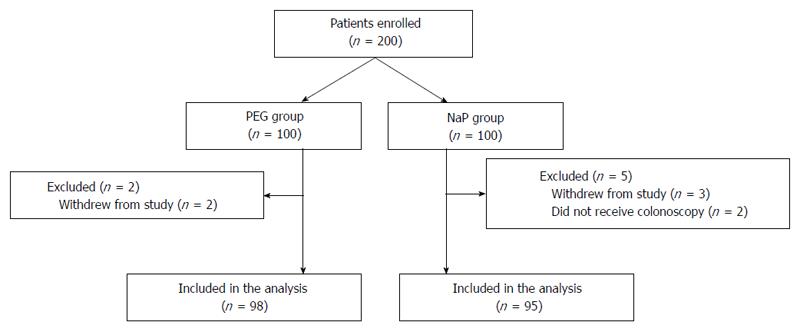

A total of 200 patients were invited to participate in the present study. Five patients withdrew from the study, and 2 patients did not come the hospital on the day of the procedure due to personal reasons (Figure 1). Finally, 193 patients (PEG group, n = 98; NaP group, n = 95) were included in this trial. The characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. A significantly higher percentage of patients in the NaP group had previously undergone colonoscopy [53 (56%) vs 38 (39%), P = 0.02].

| PEG | NaP | P value | |

| n = 98 | n = 95 | ||

| Age (range) | 49.5 (22-64) | 50 (27-64) | 0.84 |

| Sex (male) | 39 (40) | 42 (44) | 0.56 |

| Body mass index (range) | 22.9 (16.4-32.4) | 23.3 (13.1-39.3) | 0.73 |

| History of abdominal surgery | 25 (26) | 28 (30) | 0.75 |

| Stool frequency | |||

| Fewer than once a day | 20 (21) | 21 (22) | 0.86 |

| Once a day | 60 (61) | 55 (58) | 0.66 |

| Twice a day or more | 18 (18) | 19 (20) | 0.86 |

| Past colonoscopy | 38 (39) | 53 (56) | 0.02 |

| Indication for colonoscopy | |||

| FOBT positive or rectal bleeding | 55 (56) | 46 (48) | 0.31 |

| Follow-up for polyps | 20 (20) | 18 (19) | 0.86 |

| Screening | 10 (10) | 13 (14) | 0.51 |

| Change in bowel habit | 8 (8) | 13 (14) | 0.25 |

| Others | 5 (5) | 5 (5) | 1.00 |

In both groups, all of the patients were able to take the required amount of solution. The patients in the NaP group more frequently required additional solution than those in the PEG group [16 (17%) vs 5 (5%), P = 0.01]. The amount of additional solution required in each of the groups was 200-800 mL, and did not differ to a statistically significant extent (P = 0.40).

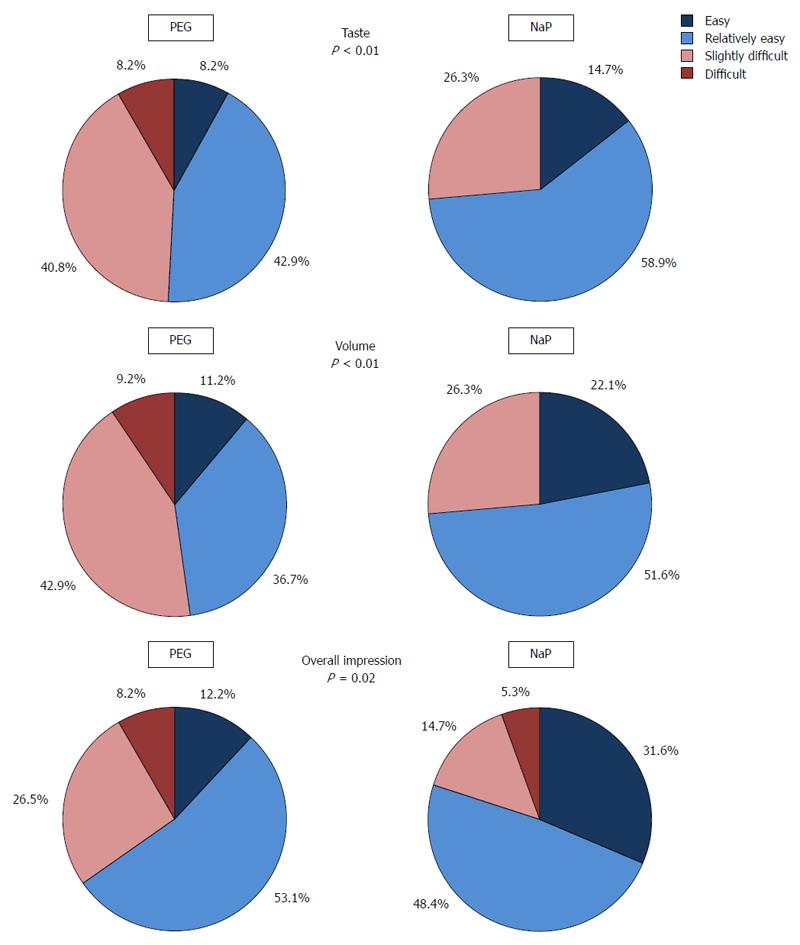

The tolerability of each laxative is shown in Figure 2. NaP was better tolerated than PEG in the indexes of taste, volume, and overall impression (easy + relatively easy: 73.6% vs 51.1%, P < 0.01; 73.7% vs 47.9%, P < 0.01; and 80.0% vs 65.3%, P = 0.02, respectively).

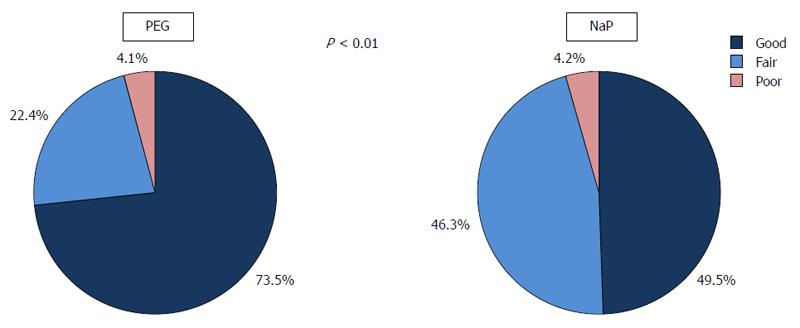

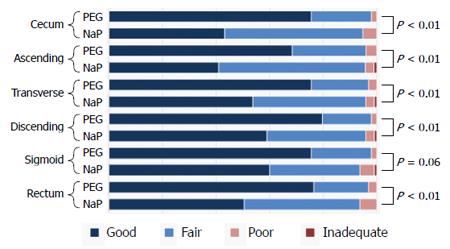

Colonoscopic observation from the rectum to the cecum was accomplished in all patients of both groups. The overall quality of bowel cleansing in the PEG group was better than that in the NaP group (good: 73.5% vs 49.5%, P < 0.01); however, the percentage of cases that were rated as “poor” were equivalently small and no cases were regarded as “inadequate” (Figure 3). Similar differences in the preparation quality were observed in nearly all of the colonic segments (Figure 4).

Among male patients, the indexes of tolerability did not differ to a statistically significant extent between the PEG and NaP groups, regardless of age (Table 2). Furthermore, the quality of bowel cleansing in the two groups did not differ to a statistically significant extent (Table 3). On the other hand, NaP was more acceptable than PEG to female patients of < 50 years of age (taste and overall impression, P = 0.01 and P < 0.01, respectively), and there was no significant difference in the quality of bowel cleansing (P = 0.07) (Table 2). In female patients of ≥ 50 years of age, although the tolerability of the laxatives did not differ to a statistically significant extent, PEG achieved a better quality of bowel cleansing (P < 0.01) (Table 3).

| Easy | Relatively easy | Slightly difficult | Difficult | P value | ||||

| Taste | Male | Age ≤ 49 | PEG | 5 | 12 | 14 | 2 | 0.36 |

| NaP | 5 | 16 | 9 | 0 | ||||

| Age ≥ 50 | PEG | 0 | 16 | 9 | 1 | 0.09 | ||

| NaP | 4 | 14 | 5 | 0 | ||||

| Female | Age ≤ 49 | PEG | 0 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 0.01 | |

| NaP | 3 | 12 | 2 | 0 | ||||

| Age ≥ 50 | PEG | 3 | 7 | 10 | 2 | 0.24 | ||

| NaP | 2 | 14 | 9 | 0 | ||||

| Volume | Male | Age ≤ 49 | PEG | 5 | 11 | 15 | 2 | 0.11 |

| NaP | 8 | 15 | 7 | 0 | ||||

| Age ≥ 50 | PEG | 3 | 12 | 10 | 1 | 0.18 | ||

| NaP | 6 | 13 | 4 | 0 | ||||

| Female | Age ≤ 49 | PEG | 0 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 0.06 | |

| NaP | 4 | 8 | 5 | 0 | ||||

| Age ≥ 50 | PEG | 3 | 6 | 10 | 3 | 0.15 | ||

| NaP | 3 | 13 | 9 | 0 | ||||

| Overall impression | Male | Age ≤ 49 | PEG | 4 | 15 | 11 | 3 | 0.05 |

| NaP | 11 | 14 | 4 | 1 | ||||

| Age ≥ 50 | PEG | 4 | 18 | 3 | 1 | 0.26 | ||

| NaP | 8 | 11 | 4 | 0 | ||||

| Female | Age ≤ 49 | PEG | 0 | 9 | 7 | 1 | < 0.01 | |

| NaP | 6 | 9 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Age ≥ 50 | PEG | 4 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 1.00 | ||

| NaP | 5 | 12 | 5 | 3 |

| Good | Fair | Poor | P value | |||

| Male | Age ≤ 49 | PEG | 22 | 9 | 2 | 0.30 |

| NaP | 15 | 14 | 1 | |||

| Age ≥ 50 | PEG | 17 | 9 | 0 | 0.22 | |

| NaP | 11 | 10 | 2 | |||

| Female | Age ≤ 49 | PEG | 13 | 3 | 1 | 0.07 |

| NaP | 7 | 9 | 1 | |||

| Age ≥ 50 | PEG | 20 | 1 | 1 | 0.01 | |

| NaP | 14 | 11 | 0 |

The insertion time and observation time in the PEG and NaP groups did not differ to a statistically significant extent (7 min vs 8 min, P = 0.3, and 10 min vs 9 min, P = 0.96, respectively).

Colonoscopy plays an important role in the detection or diagnosis of CRC, the incidence of which has been increasing. However, the bowel preparation for colonoscopy probably hampers the ability of some subjects to undergo the procedure because of its unpleasant taste and volume. In particular, the unique flavor and taste of the PEG-containing electrolyte solution, which has been widely used in preparation for colonoscopy in Japan, is not tolerated by some patients.

NaP tablets were developed in order to improve the flavor and taste associated with other solutions, such as PEG. In this regard, NaP tablets are tasteless. In addition, NaP tablets can be taken with clear liquid such as water or tea, which may make bowel preparation easier. The original NaP tablets contained microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), which remained in the colon after lavage and hampered endoscopic observation. A recently developed MCC-free product, which was used in the present study, has resolved the problem.

In the current study, we compared the tolerability and cleansing quality of low-dose NaP tablets to PEG. The results showed that low-dose NaP tablets with 2 L of clear liquid was superior to 2 L PEG from the viewpoint of patient tolerability. In contrast, PEG achieved a better cleansing quality. In particular, in the PEG group the cleansing quality was rated as “good” significantly more frequently. These results suggest that low-dose NaP should not be routinely applied to subjects undergoing colonoscopy. However, because the insertion time and observation time did not differ to a statistically significant extent, low-dose NaP may be allowable in certain situations.

A previous report compared the tolerability and quality of 30 NaP tablets with 1.2 L of clear liquid to 2 L of PEG[9]. In that study, the tolerability of NaP was also superior to that of PEG. In contrast, no significant difference was observed in the quality of bowel cleansing. Several factors may be associated with this discrepancy. Firstly, the patients in the present study took 2 L of liquid with 30 NaP tablets, whereas the patients in the previous study took 1.2 L of liquid with 30 NaP tablets. The osmotic pressure attained by 30 tablets with 1.2 L of clear liquid would be approximately 335 mOsm, which would draw extracellular fluid into the bowel and promote bowel cleansing. In contrast, the osmotic pressure established by 30 tablets with 2 L clear liquid may be lower, resulting in the inability to keep water in the intestinal canal. The low osmotic pressure in the bowel might have worsened the bowel cleansing quality in our patients. The fact that the patients in the NaP group required additional preparation more frequently than the patients in the PEG group may support this hypothesis.

It is also possible that the characteristics of our patients affected the results. The ratio of female patients in our study was higher than that in the previous study (58% vs 43%). The subgroup analysis in the present study showed that the bowel cleansing quality of PEG was significantly better than that of NaP in female patients, particularly in female patients of ≥ 50 years of age. In contrast, the preparations achieved similar effects in male patients. Thus, the larger proportion of female patients might have affected the evaluation of cleanliness.

Another study comparing the performance of 30 NaP tablets with 2 L of water to the performance of 50 NaP tablets with 2 L of water showed no significant difference in cleansing efficacy[10]. In that study, the patients who were allocated to the 30-tablet group took sodium picosulfate the night before the procedure, while the other group did not. Sodium picosulfate promotes the peristalsis of the intestines and defecation. In our study, the patients in both groups took the same volume of sodium picosulfate. The bowel cleansing quality of NaP might be augmented by sodium picosulfate.

In the present study, the results of the subgroup analysis stratified by age and gender deserve mention. In the subgroup analysis, there were no significant differences in the tolerability or quality of bowel preparation among male patients of any age. In this regard, men could choose the bowel preparation that they preferred. In female patients of < 50 years of age, NaP was better tolerated than PEG, and the cleansing quality of the two preparations did not differ to a statistically significant extent. Thus, NaP is suitable for female patients of < 50 years of age. In contrast, PEG should be recommended for female patients of ≥ 50 years of age because of its comparable tolerability and definite superiority in terms of cleansing quality. In the present study, all of the patients were ≤ 64 years of age due to safety concerns in relation to NaP. NaP is associated with the potential risk of electrolyte and renal impairment[11,12]. The age limits for this preparation have not been defined; however, one study suggested that NaP should be used for patients younger than 55 years of age who have a normal renal function[13]. In addition, our subgroup analysis indicated that the use of NaP by elderly patients had little merit. Thus, PEG should be used for such patients due to its safety and efficacy.

The present study is associated with some limitations. Firstly, it was a single center and single-blinded trial. Although a double-blinded trial would be difficult to implement in this type of study, multicenter trials may lead to more reliable data and recommendations. The unbalanced proportion of patients with a history of colonoscopy might have also been a problem because those who had previously undergone colonoscopy could compare their experience with the previous procedure. Finally, it might be more practical to compare lesion detection rates between laxatives. However, because the patients enrolled in this study were younger than 65 years of age, few patients had lesions.

The results of the present study indicated that bowel preparation with reduced-dose NaP tablets was better tolerated but achieved lower quality bowel cleansing in comparison to the usual dose of PEG. The use of 30 NaP tablets with 2 L of clear water or tea should be limited. However, in specific situations, the regimen may deserve consideration, particularly for young female patients.

We would like to thank the study participants for the time and effort. In addition, we thank the staff of Tsuyama Chuou Hospital for their help.

Colonoscopy inevitably requires bowel preparation, which is sometimes burdensome to patients. At almost all institutions in Japan, electrolyte solutions containing polyethylene glycol (PEG) or Sodium phosphate (NaP) tablets are used as a purgative for preparation. Several reports have compared the tolerability and cleansing efficacy between 2L PEG and standard-dose NaP tablets. However, the efficiency of reduced NaP tablets is not well studied.

This study demonstrates prospective clinical outcomes. The authors directly compared the tolerability and bowel cleansing quality between 2L PEG and reduced NaP tablets.

The authors set the dose of NaP tablets to 30 tablets with 2L of clear liquid. There are no report which compared reduced NaP tablets with 2L of clear liquid to 2L of PEG.

The present study indicated that bowel preparation with reduced-dose NaP tablets was better tolerated but achieved lower quality bowel cleansing in comparison to the usual dose of PEG. However, in specific situations, the regimen may deserve consideration, particularly for young female patients.

Authors reported a prospective study comparing 2L PEG with 30 tablets of NaP with 2L clear liquid. The results are useful for clinical practice and suggest that reduced-dose NaP tablet regimen was better tolerated, especially for young female patients.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Levey JM, Sali L S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Bond J, Dash C, Giardiello FM, Glick S, Johnson D. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570-1595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1423] [Cited by in RCA: 1457] [Article Influence: 85.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Adams WJ, Meagher AP, Lubowski DZ, King DW. Bisacodyl reduces the volume of polyethylene glycol solution required for bowel preparation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:229-33; discussion 233-4. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Iida Y, Miura S, Asada Y, Fukuoka K, Toya D, Tanaka N, Fujisawa M. Bowel preparation for the total colonoscopy by 2,000 ml of balanced lavage solution (Golytely) and sennoside. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1992;27:728-733. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Jung YS, Lee CK, Kim HJ, Eun CS, Han DS, Park DI. Randomized controlled trial of sodium phosphate tablets vs polyethylene glycol solution for colonoscopy bowel cleansing. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:15845-15851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee SH, Lee DJ, Kim KM, Seo SW, Kang JK, Lee EH, Lee DR. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of sodium phosphate tablets and polyethylene glycol solution for bowel cleansing in healthy Korean adults. Yonsei Med J. 2014;55:1542-1555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kambe H, Yamaji Y, Sugimoto T, Yamada A, Watabe H, Yoshida H, Omata M, Koike K. A randomized controlled trial of sodium phosphate tablets and polyethylene glycol solution for polyp detection. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:374-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hosoe N, Nakashita M, Imaeda H, Sujino T, Bessho R, Ichikawa R, Inoue N, Kanai T, Hibi T, Ogata H. Comparison of patient acceptance of sodium phosphate versus polyethylene glycol plus sodium picosulfate for colon cleansing in Japanese. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1617-1622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Aihara H, Saito S, Arakawa H, Imazu H, Omar S, Kaise M, Tajiri H. Comparison of two sodium phosphate tablet-based regimens and a polyethylene glycol regimen for colon cleansing prior to colonoscopy: a randomized prospective pilot study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:1023-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kumagai E, Shibuya T, Makino M, Murakami T, Takashima S, Ritsuno H, Ueyama H, Kodani T, Sasaki H, Matsumoto K. A Randomized Prospective Study of Bowel Preparation for Colonoscopy with Low-Dose Sodium Phosphate Tablets versus Polyethylene Glycol Electrolyte Solution. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2014;2014:879749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Koshitani T, Kawada M, Yoshikawa T. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy using standard vs reduced doses of sodium phosphate: A single-blind randomized controlled study. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:379-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mathus-Vliegen EM, Kemble UM. A prospective randomized blinded comparison of sodium phosphate and polyethylene glycol-electrolyte solution for safe bowel cleansing. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:543-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Markowitz GS, Stokes MB, Radhakrishnan J, D’Agati VD. Acute phosphate nephropathy following oral sodium phosphate bowel purgative: an underrecognized cause of chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3389-3396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hoffmanová I, Kraml P, Anděl M. Renal risk associated with sodium phosphate medication: safe in healthy individuals, potentially dangerous in others. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14:1097-1110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |