Published online Jun 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i22.4064

Peer-review started: February 14, 2017

First decision: March 3, 2017

Revised: March 20, 2017

Accepted: April 21, 2017

Article in press: April 21, 2017

Published online: June 14, 2017

Processing time: 120 Days and 13.6 Hours

To evaluate cholangioscopy in addition to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for management of biliary complications after liver transplantation (LT).

Twenty-six LT recipients with duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction who underwent ERCP for suspected biliary complications between April and December 2016 at the university hospital of Muenster were consecutively enrolled in this observational study. After evaluating bile ducts using fluoroscopy, cholangioscopy using a modern digital single-operator cholangioscopy system (SpyGlass DS™) was performed during the same procedure with patients under conscious sedation. All patients received peri-interventional antibiotic prophylaxis and bile was collected during the intervention for microbial analysis and for antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Thirty-three biliary complications were found in a total of 22 patients, whereas four patients showed normal bile ducts. Anastomotic strictures were evident in 14 (53.8%) patients, non-anastomotic strictures in seven (26.9%), biliary cast in three (11.5%), and stones in six (23.1%). A benefit of cholangioscopy was seen in 12 (46.2%) patients. In four of them, cholangioscopy was crucial for selective guidewire placement prior to planned intervention. In six patients, biliary cast and/or stones failed to be diagnosed by ERCP and were only detectable through cholangioscopy. In one case, a bile duct ulcer due to fungal infection was diagnosed by cholangioscopy. In another case, signs of bile duct inflammation caused by acute cholangitis were evident. One patient developed post-interventional cholangitis. No further procedure-related complications occurred. Thirty-seven isolates were found in bile. Sixteen of these were gram-positive (43.2%), 12 (32.4%) were gram-negative bacteria, and Candida species accounted for 24.3% of all isolated microorganisms. Interestingly, only 48.6% of specimens were sensitive to prophylactic antibiotics.

Single-operator cholangioscopy can provide important diagnostic information, helping endoscopists to plan and perform interventional procedures in LT-related biliary complications.

Core tip: Biliary complications represent a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in liver transplant recipients. To date, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography still remains the gold standard for diagnosing and treating such complications. The present study examined the benefit of complementary single-operator cholangioscopy. Our results are encouraging and demonstrate strong evidence for a diagnostic and therapeutic advantage of additional cholangioscopy for management of biliary disorders following liver transplantation.

- Citation: Hüsing-Kabar A, Heinzow HS, Schmidt HHJ, Stenger C, Gerth HU, Pohlen M, Thölking G, Wilms C, Kabar I. Single-operator cholangioscopy for biliary complications in liver transplant recipients. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(22): 4064-4071

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i22/4064.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i22.4064

Over the last few decades, the long-term outcome, morbidity, and mortality of liver transplant (LT) recipients have markedly improved because of advances in surgical techniques, modern immunosuppressive medication, and close follow-up. However, biliary complications after LT are still common[1,2]. Biliary complications affect 10%-25% of adult LT recipients[3-5]. In the majority of cases, patients present with biliary leakage and bile duct strictures. The latter can be subdivided into anastomotic and non-anastomotic strictures[6], with anastomotic strictures responding well to endoscopic treatment[3,7]. Additional biliary complications are biliary stones, cast, and sludge. Because of several disadvantages of first generation direct peroral cholangioscopy (e.g., high costs, fragility, and the prerequisite of two experienced endoscopists), introduction of this technique in 1976 initially failed to gain widespread acceptance. However, currently, cholangioscopy has become an established modality in diagnosing and treating pancreaticobiliary diseases[8,9]. In 2007, the digital single-operator per oral cholangioscopy system SpyGlass™ (Boston Scientific Corp., Natick, MA, United States) was introduced. This system featured crucial improvements in visualization and technical tools, leading to revived interest in the field of cholangioscopy for diagnosis and management of biliary disorders[10,11]. In 2015, high-resolution cholangioscopy (SpyGlass DSTM) was introduced by Boston Scientific (Boston Scientific Corp.), enabling high-definition imaging of bile ducts. The wide range of potential indications and therapeutic procedures for SpyGlass DS, such as diagnosis of indeterminate biliary strictures, lithotripsy of bile duct stones, ablative techniques for intraductal malignancies, removal of foreign bodies, and gallbladder drainage, have led to more widespread use of this procedure. A study by Chen et al[12] showed that single-operator cholangioscopy using SpyGlass was feasible and safe for diagnosis and therapy of biliary disorders. Because of the possibility of direct high-resolution imaging of bile ducts, single-operator cholangioscopy has recently attracted attention in the field of management of biliary complications after LT[13]. However, only a few case reports and small case series have analyzed the role of single-operator cholangioscopy for management of biliary complications after LT[14-16]. Moreover, most of these case series were performed using the earlier generation of the SpyGlass system. To the best of our knowledge, data on the effect of cholangioscopy using the high-resolution SpyGlass DS system on management of biliary complications in LT recipients are still unavailable.

Therefore, this study aimed to examine the role of complementary single-operator cholangioscopy using the SpyGlass DS system during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP) for management of biliary complications following LT.

This prospective, observational study was performed at the University Hospital Muenster, Germany. The study was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee. All patients gave prior written informed consent. Patients with LT and duct-to-duct biliary anastomosis who presented with clinical or biochemical signs of biliary complications, and/or suspected biliary complications based upon imaging and/or histology between April and December 2016 were consecutively included in the study. Initial imaging included transabdominal Ultrasound in all cases. In case of inconclusive findings on transabdominal ultrasound and absence of clinical evident cholangitis, additional endoscopic ultrasound was performed followed by ERCP in case of documented biliary tract alterations. During the procedures, patients received conscious sedation using propofol and piritramide with or without midazolam. All of the patients first received ERCP followed by cholangioscopy during the same procedure. ERCP was performed using a large-diameter channel duodenoscope (TJF-180V, Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Intubation of the bile duct was guidewire-assisted (0.025 inches, VisiGlideTM, Olympus Corp.) using either a catheter (StarTip2VTM, Olympus Corp.) or a sphincterotome (CleverCut2VTM, Olympus Corp.). If necessary, biliary sphincterotomy was performed.

Cholangioscopy was carried out using a single-operator cholangioscopy device (SpyGlass DS; Boston Scientific Corp.) that was pushed along the guidewire through the working channel of the duodenoscope into the bile duct. The guidewire was then removed and cholangioscopy was continued under visual guidance. A biopsy was performed in case of unclear bile duct mucosal lesions. After the intervention, patients remained at least 3 d in hospital.

The interventions were performed by two investigators rated as highly experienced with a case volume above 200 endoscopic biliary interventions/year. Procedure related complications were evaluated according to the ASGE guidelines[17].

Standard antibiotic prophylaxis included intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam at least 2 h before the procedure, and up to 3 d thereafter. During ERCP/cholangioscopy, bile was collected for microbial analysis and for antibiotic susceptibility testing.

All of the patients were maintained on a calcineurin inhibitor only or in combination with either an m-TOR-inhibitor or mycophenolate mofetil.

Strictures were determined as an abrupt narrowing of the bile duct with delayed outflow of contrast media through the stricture. Bile strictures were fluoroscopically subdivided into anastomotic strictures at the site of biliary anastomosis and non-anastomotic strictures affecting donor bile ducts that were proximal to the biliary anastomosis. Bile duct stones and biliary cast were evident as intraluminal filling defects of contrast media.

Strictures were determined as above and were visible as an abrupt substantial narrowing of bile ducts compared with distal and proximal segments of the bile duct. Biliary cast was determined as dark smooth foreign bodies mostly adhering to the bile wall, whereas stones were determined as free-moving, hard, foreign bodies in the bile duct.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 24 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). All data are presented as absolute and relative frequencies and reported as median (minimal-maximal) values. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Over the period covered by our study, 26 consecutive patients underwent ERCP followed by cholangioscopy. Their median age was 54.5 years (25-75 years), and 14 (53.8%) patients were women. Procedures were carried out after a median of 18.5 mo (1-159 mo) after LT. The patients’ clinical and demographic data, their primary underlying disease, as well as the findings of ERCP and cholangioscopy, are shown in Table 1.

| Patient no. | Age (yr) | Sex | Indication for LT | Findings of ERCP | Findings of cholangioscopy | Endoscopic Intervention |

| 1 | 64 | M | Caroli syndrome | AS, non-AS | AS, non-AS | Stent insertion |

| 2 | 65 | M | Cryptogenic liver cirrhosis | AS | AS | Balloon dilation |

| 3 | 28 | M | Cryptogenic liver cirrhosis | AS, non-AS | AS, non-AS | Balloon dilation |

| 4 | 48 | M | Transplant dysfunction | Normal | Bile duct erythema | None |

| 5 | 30 | M | Alcoholic liver cirrhosis | AS, non-AS | AS, non-AS | Balloon dilation |

| 6 | 63 | M | Hepatocellular carcinoma, alcoholic liver cirrhosis | Normal | Normal | None |

| 7 | 56 | F | Alcoholic liver cirrhosis | AS | AS | Balloon dilation |

| 8 | 48 | F | Autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis | Non-AS | Non-AS | Balloon dilation |

| 9 | 46 | M | Acute liver failure | Stones | Stones | Extraction of stones |

| 10 | 70 | M | Hepatocellular carcinoma/hepatits C | AS | AS, stones | Balloon dilation, extraction of stones |

| 11 | 75 | F | Autoimmune hepatitis and primary biliary cholangitis | AS | AS, stones | Extraction of stones, stent insertion |

| 12 | 51 | F | Cryptogenic liver cirrhosis | AS, non-AS | AS, non-AS | Balloon dilation, bougienage of stricture |

| 13 | 57 | M | Alcoholic liver cirrhosis | AS | AS | Balloon dilation |

| 14 | 30 | F | Transplant dysfunction after LT for Wilson disease | AS, stones | AS, stones | Balloon dilation, extraction of stones |

| 15 | 60 | F | Drug-induced liver injury | None | None | None |

| 16 | 57 | F | Hepatitis C | Stones | Stones | Extraction of stones |

| 17 | 52 | F | Hepatocellular carcinoma/hepatitis B | None | None | None |

| 18 | 44 | F | Acute liver failure | AS | AS | Balloon dilation |

| 19 | 60 | M | Alcoholic liver cirrhosis | AS, non-AS | AS, non-AS, biliary cast | Balloon dilation, extraction of cast |

| 20 | 53 | F | Alcoholic liver cirrhosis | Non-AS | Non-AS, biliary cast | Extraction of cast |

| 21 | 25 | F | Acute liver failure | None | None | None |

| 22 | 63 | M | Non-alcoholic steato-hepatitis | AS | AS | Balloon dilation |

| 23 | 37 | M | Hepatitis C/Wilson disease | AS | AS, stones | Balloon dilation, extraction of stones |

| 24 | 63 | F | Non-alcoholic steato-hepatitis | None | Hiliar ulcer | None |

| 25 | 66 | F | Primary biliary cholangitis | None | Biliary cast | Extraction of cast |

| 26 | 34 | F | FAP | Bile duct kinking | Bile duct kinking | Stent insertion |

A total of 33 biliary tract complications were diagnosed in 22 patients. Anastomotic strictures were observed in 14 (53.8%) patients, non-anastomotic strictures in seven (26.9%), biliary cast in three (11.5%), and stones in six (23.1%).

In four patients, no bile tree abnormalities were detected. Final diagnoses were confirmed by clinical follow-up, further liver biopsies, and biochemical tests. In these cases, graft rejection, drug-induced liver injury, and infections were the causative disorders.

During ERCP, anastomotic strictures were observed in 14 patients, non-anastomotic in seven, and stones in three. One patient showed bile duct kinking. In seven patients, ERCP showed no pathological results.

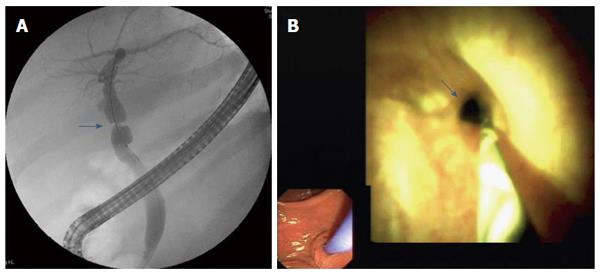

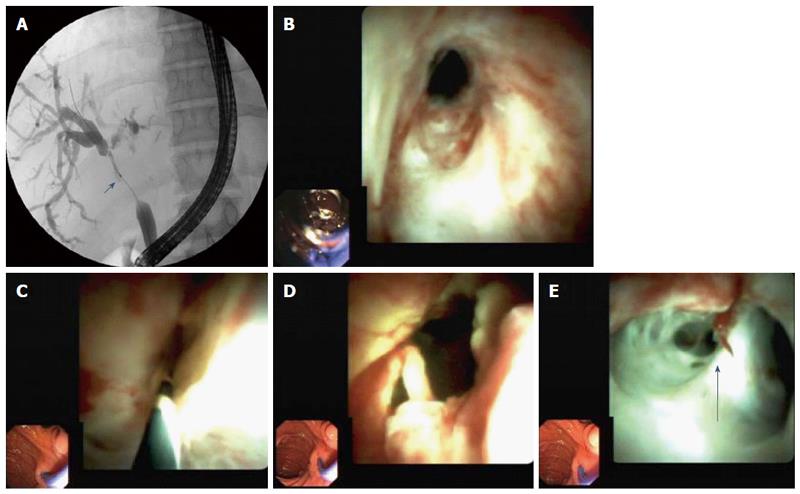

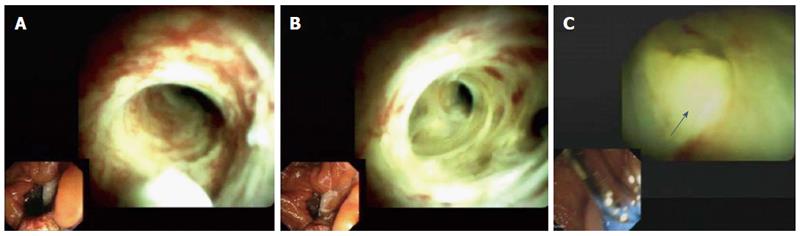

Cholangioscopy showed anastomotic strictures in 14 patients (Figure 1), non-anastomotic strictures in seven (Figure 2), biliary cast in three, and stones in six. All cases of non-anastomotic strictures showed a fibrotic obstruction and signs of inflammation, such as hyperemia, erosions, and polyp-like tissue growth. In one case, a fungal ulcer confirmed by microbiology was detected. In another case, bile duct hyperemia of intrahepatic bile ducts was found (Figure 3).

Benefits of cholangioscopy over ERCP were found in 12 of 26 (46.2%) patients. In four cases of failed cannulation of biliary strictures during ERCP, selective guidewire placement was successful by cholangioscopy under direct vision. Furthermore, cholangioscopy was superior to ERCP for detecting stones in three patients (P < 0.008) and cast in three patients (P < 0.001) that ERCP failed to detect in these patients. In one patient, a fungal bile duct ulcer that was confirmed by microbiology (candidiasis) was detected, and this resulted in targeted antifungal therapy. In another patient, strong hyperemia of intrahepatic bile ducts due to acute cholangitis was observed.

A total of 11 biopsies were obtained. Histological samples showed fibrotic shrinkage without inflammation in case of anastomotic strictures. In a patient with non-anastomotic strictures, signs of acute and chronic inflammation with mixed infiltration of lymphocytes, plasmacytes, and granulocytes, as well as granulation tissue and scars, were observed. In a patient with hyperemia, inflammation with predominantly granulocytes was observed. In this patient, bacterial cholangitis was confirmed by the clinical course and microbiologically.

In patients with biliary complications, a total of 13 balloon dilatations, six extractions of stones, three stent insertions, one bougienage of a tight stricture, and three extractions of biliary cast were performed. Only one procedure-related complication (cholangitis) occurred and was managed antibiotically.

Bile was collected from 23 patients. In seven (30.4%) patients, the bile showed no microbial growth. In 16 (69.6%) patients, bacteria and/or fungi were detected. In nine (39.1%) patients, Candida species were observed (Candida albicans in six cases, and C. duliniensis, C. glabrata, and C tropicalis in one patient each).

A total of 37 microorganisms were isolated from the bile. Of these, 16 were gram-positive (43.2%), whereas 12 (32.4%) were gram-negative bacteria. Candida species accounted for 24.3% of all isolates. The microorganisms that were found in bile are listed in Table 2.

| Microorganism | Frequency | Percentage |

| Stenotrophomonas | 1 | 2.7% |

| Enterococcus faecium | 7 | 18.9% |

| Escherichia coli | 5 | 13.5% |

| Streptococcus viridans | 2 | 5.4% |

| Micrococcus luteus | 1 | 2.7% |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 2 | 5.4% |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 2 | 5.4% |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 2 | 5.4% |

| Raultella ornithinolytica | 1 | 2.7% |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 1 | 2.7% |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus | 1 | 2.7% |

| Pedicoccus pentosaceus | 1 | 2.7% |

| Enterococcus avium | 2 | 5.4% |

| Candida albicans | 6 | 16.2% |

| Candida duliniensis | 1 | 2.7% |

| Candida tropicalis | 1 | 2.7% |

| Candida glabrata | 1 | 2.7% |

| Total | 37 | 100% |

In patients with evidence of bile colonization, standard antibiotic prophylaxis using piperacillin/tazobactam was effective in only 48.6% of all isolates. Susceptibility testing for ciprofloxacin showed that 36.1% of isolates were sensitive, whereas 58.3% were resistant and 5.6% were intermediate susceptible. For ceftriaxone, 70.3% of microorganisms were resistant and 29.7% were sensitive. Among all specimens, 54.1% were sensitive to carbapenems. For gentamicin, 32.4% were resistant, 55.6% were sensitive, and 11.1% were intermediate susceptible to this antibiotic. For vancomycin, 87.5% of the tested gram-positive bacteria were sensitive. For tigecycline, 62.5% of all tested specimens were also sensitive.

Of all fungal isolates, eight were sensitive to triazoles, while one was intermediate susceptible. All isolated Candida species were susceptible to amphotericin B and echinocandins.

Despite improvements in surgical techniques, biliary complications are common and still considered the “Achilles heel” of LT[18,19]. To date, ERCP represents the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment of biliary complications after LT[20,21]. However, increasing evidence is currently emerging of the major benefits of using cholangioscopy in management of these biliary disorders.

In our study, an advantage of cholangioscopy over ERCP was observed in 12 of 26 (46.2%) patients. In one case series by Woo et al[13] SpyGlass cholangioscopy showed a high performance in visualization of strictures, but a poor performance of cholangioscopy-assisted guidewire placement in 60% of cases. In contrast to these findings, we were able to selectively steer the guidewire over the stricture in every patient prior to planned treatment. An explanation of the poor success of guidewire placement in Woo et al[13] study could be that their study was performed in patients after living donor LT, with special and sometimes complex anatomy of bile ducts. However, most of our patients underwent whole cadaveric LT prior to the procedure (only one patient in our cohort had a living donor LT). The use of the new generation of high-resolution cholangioscopy (SpyGlass DSTM) in our study may have provided an additional advantage.

In our study, cholangioscopy was superior to ERCP in detection of stones and biliary cast. Several previous studies showed that the sensitivity of ERCP in detecting bile duct stones ranged between 89% and 93%. Especially in cases of small stones and dilated bile ducts, false negative ERCP has been observed[22-24]. In a previous study at our center, we found that biliary cast appear to be underdiagnosed using ERCP only[21]. Biliary stones and cast can be masked by dense contrast media during ERCP. Furthermore, stones and cast in bile ducts may be easily misinterpreted as biliary air. In the present study, ERCP failed to identify biliary cast in three patients and biliary stones in a further three patients. In two of the three patients with failed diagnosis of cast, further biliary tract disorders were coincident. In one of these patients, anastomotic stricture and multiple non-anastomotic strictures were found. In another of these patients, multiple non-anastomotic strictures were observed. These additional conditions could have made it even more difficult to identify biliary cast. In the third patient, biliary cast was detected only in the intra-hepatic bile ducts and was adhered to the bile duct wall without completely occluding the whole bile duct lumen. In all patients in whom ERCP failed to detect stones, anastomotic stricture was also present, and small stones were detected by cholangioscopy directly proximal to the anastomosis. This was most likely as a consequence of bile stasis caused by stenosis. The coincident anastomotic stricture and bile duct dilation could have masked the small stones in these special cases. One further advantage for cholangioscopy was found in patients in whom pathological changes in bile ducts (e.g., hyperemia and bile duct ulcers; Figure 1) were only detectable by direct visualization of bile duct walls, but not by fluoroscopy. In these special cases, there were therapeutic consequences. In the current study, ERCP was highly effective in detecting bile duct strictures. In these cases, cholangioscopy offered no further benefits.

In our study, additional histological information that was obtained by tissue samples of the bile duct was of minor clinical relevance. In the case of non-anastomotic strictures, fibrosis and inflammation were simultaneously evident in every patient. This finding supports the role of ongoing inflammation for the pathogenesis of non-anastomotic strictures. Our findings are consistent with the results of previous studies suggesting immunological aspects in the pathogenesis of non-anastomotic strictures[3,25].

During endoscopic procedures, we obtained bile samples for microbial analysis in the majority of patients. Several studies have identified LT as a risk factor for increasing microbial colonization of bile. In these studies, an increased incidence of gram-positive bacteria with increasing antibiotic resistance, such as enterococci and Candida species, in patients with LT was found[26-29]. In our study, we found a remarkably high prevalence of Candida species (39.1%), whereas the prevalence of enterococci was 29.7%. In a minority of isolates (48.6%), specimens that were found in bile were sensitive to administered prophylactic antibiotics. These findings are important because microbial colonization of bile has been identified to be the origin of post-ERCP cholangitis and cholangiosepsis[26]. Even though microbial analysis was not the focus of the present study, these findings suggest that bile colonization during endoscopic interventions in the bile duct of LT recipients should be monitored. The resulting resistogram can be helpful in choosing effective antibiotics in case of endoscopy-related septic complications. Because of the high prevalence of enterococci and Candida species, empirical antimicrobial treatments should include vancomycin/linezolid and an antifungal agent in case of post-procedural septic complications. Isolated Candida species showed no relevant resistance to common antifungal agents in our study. However, selection of an antibiotic regimen should always be based on local microbial resistance patterns.

In conclusion, high-resolution cholangioscopy using the SpyGlass DS system is safe and feasible in LT recipients with biliary complications, and offers useful diagnostic information in addition to ERCP. Cholangioscopy is superior to ERCP in diagnosing biliary cast and stones, and optimizes treatment in the patients concerned. Therefore, we recommend performing cholangioscopy in LT recipients who have negative ERCP results and suspected biliary complications.

Use of a general peri-interventional antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with LT based on the general increase in microbial resistance should be critically examined in future studies. Furthermore, microbial analysis of bile collected during bile duct interventions should be regularly performed to adapt anti-infective treatments in case of post-ERCP septic complications.

We also acknowledge the support of Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Open Access Publication Fund of University of Muenster.

Despite improvements in surgical techniques, biliary complications still remain common in liver transplant (LT) recipients influencing their morbidity and mortality. Nowadays, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) represents the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment of biliary complications following LT. Until now, data evaluating the utility and value of cholangioscopy for management of biliary disorders after LT are still lacking.

The present study explores the benefit of modern digital single-operator cholangioscopy (SpyGlass DS™) in addition to ERCP for the management of biliary complications after LT.

The results of our study indicate that use of cholangioscopy provides valuable diagnostic information which is able to improve the management of biliary complications after LT.

These data demonstrate that cholangioscopy is effective for selective guidewire placement in high-grade biliary strictures that failed to be cannulated using ERCP alone. Furthermore, cholangioscopy offers diagnostic superiority in comparison to ERCP in detecting biliary cast and stones and therefore should be used in LT recipients with clinical signs of biliary complications despite negative ERCP results.

Single-operator cholangioscopy is an innovative tool that enables high-resolution imaging of bile ducts.

The manuscript is fine and well written. In addition the manuscript is useful for physician facing with post liver transplant complication clearly documenting the superiority of cholangioscopy with respect to ERCP. Interestingly the superiority is clearly documented for biliary stones, casts and unusual, but diverse finding as micotic ulcer.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kawakami H, Salvadori M S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Duffy JP, Kao K, Ko CY, Farmer DG, McDiarmid SV, Hong JC, Venick RS, Feist S, Goldstein L, Saab S. Long-term patient outcome and quality of life after liver transplantation: analysis of 20-year survivors. Ann Surg. 2010;252:652-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Graziadei IW, Schwaighofer H, Koch R, Nachbaur K, Koenigsrainer A, Margreiter R, Vogel W. Long-term outcome of endoscopic treatment of biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:718-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Williams ED, Draganov PV. Endoscopic management of biliary strictures after liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3725-3733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ryu CH, Lee SK. Biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Gut Liver. 2011;5:133-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pascher A, Neuhaus P. Bile duct complications after liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2005;18:627-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sharma S, Gurakar A, Jabbour N. Biliary strictures following liver transplantation: past, present and preventive strategies. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:759-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kao D, Zepeda-Gomez S, Tandon P, Bain VG. Managing the post-liver transplantation anastomotic biliary stricture: multiple plastic versus metal stents: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:679-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Erim T, Shiroky J, Pleskow DK. Cholangioscopy: the biliary tree never looked so good! Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29:501-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Singh A, Gelrud A, Agarwal B. Biliary strictures: diagnostic considerations and approach. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2015;3:22-31. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Laleman W, Verraes K, Van Steenbergen W, Cassiman D, Nevens F, Van der Merwe S, Verslype C. Usefulness of the single-operator cholangioscopy system SpyGlass in biliary disease: a single-center prospective cohort study and aggregated review. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:2223-2232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ishida Y, Itoi T, Okabe Y. Types of Peroral Cholangioscopy: How to Choose the Most Suitable Type of Cholangioscopy. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2016;14:210-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen YK, Pleskow DK. SpyGlass single-operator peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy system for the diagnosis and therapy of bile-duct disorders: a clinical feasibility study (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:832-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Woo YS, Lee JK, Noh DH, Park JK, Lee KH, Lee KT. SpyGlass cholangioscopy-assisted guidewire placement for post-LDLT biliary strictures: a case series. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:3897-3903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Balderramo D, Sendino O, Miquel R, de Miguel CR, Bordas JM, Martinez-Palli G, Leoz ML, Rimola A, Navasa M, Llach J. Prospective evaluation of single-operator peroral cholangioscopy in liver transplant recipients requiring an evaluation of the biliary tract. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:199-206. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Navaneethan U, Venkatesh PG, Al Mohajer M, Gelrud A. Successful diagnosis and management of biliary cast syndrome in a liver transplant patient using single operator cholangioscopy. JOP. 2011;12:461-463. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Franzini T, Moura R, Rodela G, Andraus W, Herman P, D’Albuquerque L, de Moura E. A novel approach in benign biliary stricture - balloon dilation combined with cholangioscopy-guided steroid injection. Endoscopy. 2015;47 Suppl 1:E571-E572. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Chandrasekhara V, Khashab MA, Muthusamy VR, Acosta RD, Agrawal D, Bruining DH, Eloubeidi MA, Fanelli RD, Faulx AL, Gurudu SR. Adverse events associated with ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:32-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in RCA: 529] [Article Influence: 66.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ayoub WS, Esquivel CO, Martin P. Biliary complications following liver transplantation. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1540-1546. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Safdar K, Atiq M, Stewart C, Freeman ML. Biliary tract complications after liver transplantation. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;3:183-195. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Arain MA, Attam R, Freeman ML. Advances in endoscopic management of biliary tract complications after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:482-498. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Hüsing A, Cicinnati VR, Beckebaum S, Wilms C, Schmidt HH, Kabar I. Endoscopic ultrasound: valuable tool for diagnosis of biliary complications in liver transplant recipients? Surg Endosc. 2015;29:1433-1438. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Tseng LJ, Jao YT, Mo LR, Lin RC. Over-the-wire US catheter probe as an adjunct to ERCP in the detection of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:720-723. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Prat F, Amouyal G, Amouyal P, Pelletier G, Fritsch J, Choury AD, Buffet C, Etienne JP. Prospective controlled study of endoscopic ultrasonography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in patients with suspected common-bileduct lithiasis. Lancet. 1996;347:75-79. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Benjaminov F, Stein A, Lichtman G, Pomeranz I, Konikoff FM. Consecutive versus separate sessions of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for symptomatic choledocholithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2117-2121. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Guichelaar MM, Benson JT, Malinchoc M, Krom RA, Wiesner RH, Charlton MR. Risk factors for and clinical course of non-anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:885-890. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Negm AA, Schott A, Vonberg RP, Weismueller TJ, Schneider AS, Kubicka S, Strassburg CP, Manns MP, Suerbaum S, Wedemeyer J. Routine bile collection for microbiological analysis during cholangiography and its impact on the management of cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:284-291. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Millonig G, Buratti T, Graziadei IW, Schwaighofer H, Orth D, Margreiter R, Vogel W. Bactobilia after liver transplantation: frequency and antibiotic susceptibility. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:747-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gotthardt DN, Weiss KH, Rupp C, Bode K, Eckerle I, Rudolph G, Bergemann J, Kloeters-Plachky P, Chahoud F, Büchler MW. Bacteriobilia and fungibilia are associated with outcome in patients with endoscopic treatment of biliary complications after liver transplantation. Endoscopy. 2013;45:890-896. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Kabar I, Hüsing A, Cicinnati VR, Heitschmidt L, Beckebaum S, Thölking G, Schmidt HH, Karch H, Kipp F. Analysis of bile colonization and intestinal flora may improve management in liver transplant recipients undergoing ERCP. Ann Transplant. 2015;20:249-255. [PubMed] |