Published online Jan 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i2.318

Peer-review started: September 21, 2016

First decision: October 20, 2016

Revised: October 29, 2016

Accepted: November 16, 2016

Article in press: November 16, 2016

Published online: January 14, 2017

Processing time: 114 Days and 3.6 Hours

To assess the clinical characteristics of patients with complicated erosive esophagitis (EE) and their associated factors.

This prospective, cross-sectional study included patients diagnosed with EE by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy between October 2014 and March 2015 at 106 Japanese hospitals. Data on medical history, general condition, gastrointestinal symptoms, lifestyle habits, comorbidities, and endoscopic findings were collected using a standard form to create a dedicated database. Logistic regression analysis was used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95%CI for the association with complicated EE.

During the study period, 1749 patients diagnosed with EE, 38.3% of whom were prescribed proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) were included. Of them, 143 (8.2%) had EE complications. Esophageal bleeding occurred in 84 (4.8%) patients, esophageal strictures in 45 (2.6%) patients, and 14 (0.8%) patients experienced both. Multivariate analysis showed that increased age (aOR: 1.05; 95%CI: 1.03-1.08), concomitant use of psychotropic agents (aOR: 6.51; 95%CI: 3.01-13.61), and Los Angeles grades B (aOR: 2.69; 95%CI: 1.48-4.96), C (aOR: 15.38; 95%CI: 8.62-28.37), and D (aOR: 71.49; 95%CI: 37.47-142.01) were significantly associated with complications, whereas alcohol consumption 2-4 d/wk was negatively associated (aOR: 0.23; 95%CI: 0.06-0.61). Analyzing associated factors with each EE complication separately showed esophageal ulcer bleeding were associated with increased age (aOR: 1.05; 95%CI: 1.02-1.07) and Los Angeles grades B (aOR: 3.60; 95%CI: 1.52-8.50), C (aOR: 27.61; 95%CI: 12.34-61.80), and D (aOR: 119.09; 95%CI: 51.15-277.29), while esophageal strictures were associated with increased age (aOR: 1.07; 95%CI: 1.04-1.10), gastroesophageal reflux symptom (aOR: 2.51; 95%CI: 1.39-4.51), concomitant use of psychotropic agents (aOR: 11.79; 95%CI: 5.06-27.48), Los Angeles grades C (aOR: 7.35; 95%CI: 3.32-16.25), and D (aOR: 20.34; 95%CI: 8.36-49.53) and long-segment Barrett’s esophagus (aOR: 4.63; 95%CI: 1.64-13.05).

Aging and severe EE were common associated factors, although there were more associated factors in esophageal strictures than esophageal ulcer bleeding. Despite the availability and widespread use of PPIs, EE complications are likely to remain a problem in Japan owing to the aging population and high-stress society.

Core tip: This nationwide prospective survey in Japan evaluated the clinical characteristics of complicated erosive esophagitis (EE) and its associated factors at the time of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) availability in real-world clinical settings. Our results indicate that aging and severe EE were common associated factors, although there were more associated factors in esophageal strictures than esophageal ulcer bleeding, indicating that pathophysiology of esophageal strictures was more complex than esophageal ulcer bleeding. Despite the availability and widespread use of PPIs, EE complications are likely to remain a problem in Japan owing to the aging population and high-stress society.

- Citation: Sakaguchi M, Manabe N, Ueki N, Miwa J, Inaba T, Yoshida N, Sakurai K, Nakagawa M, Yamada H, Saito M, Nakada K, Iwakiri K, Joh T, Haruma K. Factors associated with complicated erosive esophagitis: A Japanese multicenter, prospective, cross-sectional study. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(2): 318-327

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i2/318.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i2.318

The prevalence of erosive esophagitis (EE) was previously considered much lower in Asian countries, including Japan, than in Western countries[1]. In recent years, however, the prevalence of EE has increased in Japan[2,3]. The major esophageal complications of EE include ulcer bleeding and strictures. Although death from EE is uncommon, these complications are associated with significant morbidity and mortality rates[4].

Because reflux of acidic gastric contents into the esophagus plays a major role in the pathogenesis of EE, acid suppression is currently the most effective therapeutic approach. During the last two decades, many pharmacological studies and large clinical trials have shown the superiority of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) over other drugs, including antacids, prokinetics, and H2-receptor antagonists[5]. PPIs are now considered the mainstay of anti-reflux treatment and are extensively prescribed, not only by gastroenterologists and general practitioners but also by non-GI specialists[6]. Although the ready availability and widespread use of PPIs have altered the presentation of complicated EE, little is known about its epidemiology. This nationwide prospective survey in Japan therefore evaluated the frequency of complicated EE and its associated factors at the time of PPI availability in real-world clinical settings.

This multicenter, prospective, cross-sectional survey was conducted between October 2014 and March 2015 by members of the Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) Society, a Japanese GERD study group, at 106 centers located throughout Japan. These centers included 26 university hospitals, 76 public hospitals, and four national hospitals. This study included all patients with a final diagnosis of EE. The demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients were evaluated, including medical history, general condition, gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, lifestyle habits, comorbidities, and endoscopic findings. Each hospital recorded detailed information on EE patients and sent this information to a central database. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethical Guidelines for Clinical Research issued by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, and was approved by the ethics committee of each center and of Kawasaki Medical School, Kurashiki, Japan (Study Number: 1883). This study was registered at the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN registration ID: UMIN000014157).

All consecutive patients aged ≥ 50 years with a final diagnosis of EE were enrolled in this study. EE was defined as mucosal breaks on the esophagus and categorized as Los Angeles (LA) classification grades A, B, C and D[7]. All included patients provided written informed consent. EE patients were excluded if they had a history of malignancy, GI resection, gastrostomy, or endoscopic resection (including endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection).

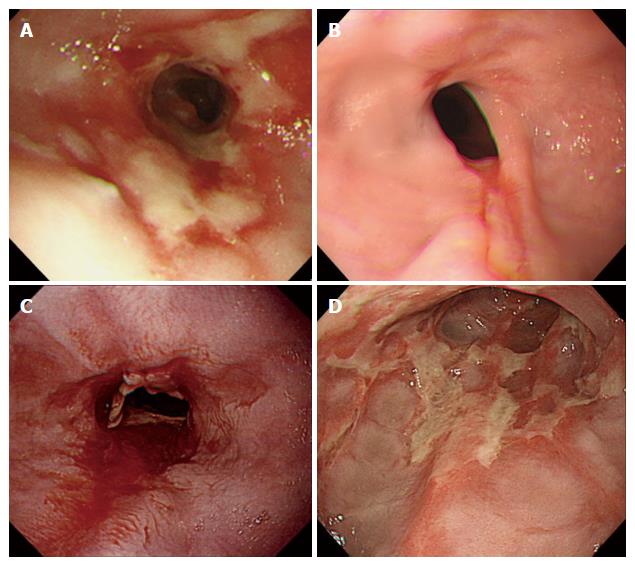

EE-related complications, including esophageal ulcer bleeding, strictures, and perforation, were recorded. The endoscopic extent of gastric mucosal atrophy was classified as described[8]. Long-segment Barrett’s esophagus was diagnosed by endoscopic identification of columnar epithelium extending more than 3 cm into the esophagus without histological evidence of intestinal metaplasia. Concurrent findings during endoscopy, such as hiatus hernia, gastritis, or gastroduodenal ulcers were also recorded. The judging panel consisted of four endoscopic specialists (KH, TJ, KN, and KI) qualified by the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society made the final diagnosis of EE complications. If the panel could not reach a consensus diagnosis on EE-related complications, the patient in question was excluded from those with EE-related complications (Figure 1).

Each doctor who participated in this research study conducted face-to-face interviews with all participants using a questionnaire made for this study. Information obtained via the questionnaire included patient characteristics, EE treatment, concomitant drugs, comorbidities, and lifestyle, including alcohol consumption, smoking status, and general condition (nasogastric feeding, bedridden, or both). Other patient characteristics included sex, age, height, body weight, and GI symptoms at the time of the endoscopy. Height and body weight were used to calculate body mass index. Reflux symptoms were based on patient reports of heartburn and acid regurgitation. If patients complained of reflux symptoms, the duration of each symptom was determined. Upper GI symptoms were based on patient reports of epigastric pain, epigastric burning, heavy stomach feeling, and early satiety. Lower GI symptoms were based on patient reports of abdominal fullness, constipation, and diarrhea. Infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) was defined as at least one positive result on the following tests: histology, culture, rapid urease tests using endoscopic biopsy specimens, H. pylori-specific antibody in patient serum, urea breathing test, or stool antigen test. Patients were classified as never smokers, ex-smokers or current smokers. Regarding alcohol intake, patients were classified as never drinkers, ex-drinkers or current drinkers. Patients classified as current drinkers were subclassified by weekly frequency of drinking as less than once, two to four times, or five or more times.

The primary end-point was the clinical characteristics of patients with EE-related complications, including esophageal ulcer bleeding and strictures. The secondary end-point was to clarify the factors associated with complicated EE.

Continuous variables are reported as mean and SD, whereas categorical variables are reported as percentages. Student’s t-tests were used to compare two independent groups. The χ2 test (with Yates correction, if required) was used to compare percentages. Logistic regression analysis was used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95%CIs for the association with complications of EE. Multivariate logistic regression analysis included all factors determined by univariate analysis to be associated with complications. OR was regarded as an estimate of the relative risk of factors associated with complicated EE. Statistical significance was defined at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP 12.0.1 and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States).

During the study period between October 2014 and March 2015, 1817 were diagnosed with EE. Of them, 68 (3.7%) were excluded for the following reasons: age < 50 years (61 patients), insufficient data (four patients), history of GI surgery (two patients), and lack of esophageal mucosal breaks (one patient). The study cohort therefore consisted of 1749 participants (1044 men and 705 women, mean age 68.0 ± 9.6). Of these patients, 995, 508, 162, and 84 were diagnosed with LA grades A, B, C, and D, respectively. Of the 1,749 patients with EE, 143 (8.2%) had complications, including 84 (4.8%) with esophageal ulcer bleeding, 45 (2.6%) with esophageal strictures, and 14 (0.8%) with both.

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the 143 EE patients with complications and the 1606 without complications. The presence of complications was associated with older age, female sex, and being bedridden. The percentage of EE patients with reflux-related symptoms was higher in patients who had complications than in those without complications (Table 2), although their duration of heartburn symptoms did not differ significantly (P = 0.226). Other GI symptoms, including epigastric pain, epigastric burning, and constipation, were more frequent in EE patients with than without complications (Table 2). There were a higher percentage of current drinkers (two to four times per week frequency) among patients with uncomplicated EE than with complicated EE. Smoking status did not differ significantly in these two groups (Table 1). Patients with EE complications had more severe EE on endoscopy than those without complications (Table 3). The frequency of endoscopic gastric mucosal atrophy, defined by the Kimura-Takemoto classification (C1-O3), was similar in the two groups. The rates of hiatal hernia and Barrett’s epithelium were higher in patients with than without EE-related complications. Assessments of comorbidities showed that cerebral infarction, dementia, and kyphosis occurred more frequently in EE patients with than without complications (Table 1), and that patients with complications used more antiplatelet agents (except aspirin), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and psychoactive drugs. PPI prescribing differed significantly in the two groups, although previous history of EE did not (Table 1).

| With complications (n = 143) | Without complications (n = 1606) | P value | |

| Sex (M/F) | 74/69 | 970/636 | 0.043 |

| Age (years old) | 74.4 ± 11.0 | 67.4 ± 9.2 | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.2 ± 3.8 | 23.8 ± 3.5 | 0.074 |

| General condition (tube-fed/bedridden/tube-fed + bedridden) | 0/8/0 | 1/5/1 | < 0.001 |

| Consultation behavior (outpatient/inpatient/emergency patient) | 90/26/27 | 1511/83/12 | < 0.001 |

| Smoking (never/current smoker/ex-smoker) | 94/16/33 | 955/234/417 | 0.311 |

| Duration of smoking cessation (yr) | 16.8 ± 13.7 | 14.5 ± 13.3 | 0.359 |

| Alcohol drinking | < 0.001 | ||

| Never | 76 (53.1) | 711 (44.3) | |

| Current | |||

| < 1 d per week | 10 (7.0) | 199 (12.4) | |

| 2-4 d per week | 4 (2.8) | 192 (12.0) | |

| > 5 d per week | 38 (26.6) | 432 (26.9) | |

| Ex-drinker | 15 (10.5) | 72 (4.5) | |

| Duration of drinking cessation (yr) | 8.8 ± 9.7 | 9.0 ± 10.8 | 0.957 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 71 (49.7) | 724 (45.1) | 0.293 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 26 (18.2) | 282 (17.6) | 0.851 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 33 (23.1) | 391 (24.3) | 0.734 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 22 (15.4) | 83 (5.2) | < 0.001 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 4 (2.8) | 30 (1.9) | 0.441 |

| Ischemic cardiac disease | 13 (9.1) | 85 (5.3) | 0.058 |

| Collagen disease | 6 (4.2) | 34 (2.1) | 0.111 |

| Dementia | 13 (9.1) | 11 (0.7) | < 0.001 |

| Kyphosis | 11 (7.7) | 36 (2.2) | < 0.001 |

| PPI treatment status | 0.001 | ||

| Never | 20 (27.4) | 395 (50.4) | |

| Continuation therapy | 40 (54.8) | 251 (32.1) | |

| On-demand therapy | 2 (2.7) | 35 (4.5) | |

| Cessation | 11(15.1) | 102 (13.0) | |

| Concomitant medication | |||

| Antithrombogenic | 31 (21.7) | 216 (13.5) | 0.007 |

| Aspirin | 12 (8.4) | 97 (6.0) | 0.265 |

| Antiplatelet agent | 15 (10.5) | 89 (5.5) | 0.017 |

| Anticoagulant agent | 8 (5.6) | 60 (3.7) | 0.271 |

| Antihypertensive drug | 58 (40.6) | 615 (38.3) | 0.594 |

| NSAID | 17 (11.9) | 91 (5.7) | 0.003 |

| Psychotropic | 16 (11.2) | 40 (2.5) | < 0.001 |

| With complications (n = 143) | Without complications (n = 1606) | P value | |

| Upper GI symptoms | |||

| Heartburn | 86 (60.1) | 773 (48.1) | 0.006 |

| Regurgitation | 54 (37.8) | 428 (26.7) | 0.004 |

| Epigastric pain | 34 (23.8) | 261 (16.3) | 0.022 |

| Epigastric burning | 28 (19.6) | 149 (9.3) | < 0.001 |

| Heavy stomach feeling | 42 (29.4) | 398 (24.8) | 0.227 |

| Early satiety | 19 (13.3) | 136 (8.5) | 0.052 |

| Lower GI symptoms | |||

| Abdominal Bloating | 10 (7.0) | 165 (10.3) | 0.210 |

| Constipation | 39 (27.3) | 277 (17.2) | 0.003 |

| Diarrhea | 7 (4.9) | 117 (7.3) | 0.286 |

| Constipation/diarrhea | 5 (3.5) | 39 (2.4) | 0.434 |

| With complications (n = 143) | Without complications (n = 1606) | P value | |

| Los Angeles classification | < 0.001 | ||

| A | 19 (13.3) | 976 (60.8) | |

| B | 30 (21.0) | 478 (29.8) | |

| C | 43 (30.1) | 119 (7.4) | |

| D | 51 (35.7) | 33 (2.1) | |

| Gastric mucosal atrophy | 82 (57.3) | 930 (57.9) | 0.464 |

| Hiatal hernia | 123 (86.0) | 1070 (66.6) | < 0.001 |

| Barrett’s epithelium | 8 (5.6) | 24 (1.5) | < 0.001 |

| H. pylori infection | < 0.001 | ||

| Positive | 10 (7.0) | 134 (8.3) | |

| Negative | 31 (21.7) | 677 (42.2) | |

| Unknown | 102 (71.3) | 795 (49.5) |

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine the factors associated with EE complications. Six factors were found to be significantly and independently associated with complications: increased age [adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 1.05; 95%CI: 1.03-1.08, P < 0.001], concomitant use of psychotropic agents (aOR: 6.51; 95%CI: 3.01-13.61, P < 0.001), and LA grades B (aOR: 2.69; 95%CI: 1.48-4.96, P = 0.001), C (aOR: 15.38; 95%CI: 8.62-28.37, P < 0.001) and D (aOR: 71.49; 95%CI: 37.47-142.01, P < 0.001). In contrast, consumption of alcohol two to four times per week showed a significant negative association with EE complications (aOR: 0.23; 95%CI: 0.06-0.61, P = 0.008) (Table 4).

| Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value | |

| Ages | 1.05 (1.03-1.08) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol drinking | ||

| Never | 1.00 | - |

| < 1 d per week | 0.73 (0.32-1.52) | 0.425 |

| 2-4 d per week | 0.23 (0.06-0.61) | 0.008 |

| > 5 d per week | 1.32 (0.80-2.14) | 0.268 |

| Concomitant medication: psychotropic agent | 6.51 (3.01-13.61) | < 0.001 |

| Los Angeles classification grade | ||

| A | 1.00 | - |

| B | 2.69 (1.48-4.96) | 0.001 |

| C | 15.38 (8.62-28.37) | < 0.001 |

| D | 71.49 (37.47-142.01) | < 0.001 |

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine the factors associated with esophageal ulcer bleeding. Four factors were found to be significantly and independently associated with complications: increased age (aOR: 1.05; 95%CI: 1.02-1.07, P < 0.001), LA grades B (aOR: 3.60; 95%CI: 1.52-8.50, P = 0.004), C (aOR: 27.61; 95%CI: 12.34-61.80, P < 0.001) and D (aOR: 119.09; 95%CI: 51.15-277.29, P < 0.001).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine the factors associated with esophageal strictures. Seven factors were found to be significantly and independently associated with complications: increased age (aOR: 1.07; 95%CI: 1.04-1.10, P < 0.001), reflux-related symptoms (aOR: 2.51; 95%CI: 1.39-4.51, P = 0.002), concomitant use of psychotropic agents (aOR: 11.79; 95%CI: 5.06-27.48, P < 0.001), and LA grades C (aOR: 7.35; 95%CI: 3.32-16.25, P < 0.001), D (aOR: 20.34; 95%CI: 8.36-49.53, P < 0.001) and long-segment Barrett’s esophagus (aOR: 4.63; 95%CI: 1.64-13.05, P = 0.004).

This Japanese, multicenter, prospective, cross-sectional study involving 1749 patients with EE, 38.3% of whom were prescribed PPIs, showed that 8.2% of these patients had complications, including 4.8% with esophageal ulcer bleeding, 2.6% with esophageal strictures, and 0.8% with both. On multivariate analysis, increased age, concomitant use of psychotropic agents, and severe EE as defined by LA grades B-D was significantly associated with complications. Interestingly, moderate alcohol consumption showed a significant negative association with complications in patients with EE. Although several studies have evaluated risk factors for EE[9,10], this study, to our knowledge, is the first multicenter large-scale study to assess factors associated with complicated EE among Japanese patients, the majority of whom were being treated with PPIs.

Obesity, smoking, and age are risk factors for EE[11-16], with age also being considered an important risk factor for severe EE[17-19]. Age is associated with increased esophageal exposure to acid, although the severity of reflux symptoms decreases with age. These changes are associated with a progressive decrease in abdominal lower esophageal sphincter (LES) length and esophageal motility[18]. Increasing EE severity in elderly subjects, such as esophageal ulcer bleeding or stricture, is related to degradation of the gastroesophageal junction and impaired esophageal clearance. Interestingly, this study also found that concomitant treatment with psychotropic agents was an independently associated factor for complicated EE. Long-term use of psychotropic agents, such as clozapine and clomipramine, has been associated with severe esophageal dilation and hypomotility accompanied by lowered visceral sensitivity, leading to excess esophageal exposure to acid and impaired acid clearance, which are considered crucial causes of complicated EE[20]. Nevertheless, psychotropic agents differed in the ability to influence the pathophysiology of EE[21,22]. This study, however, did not evaluate the relationships of complicated EE with the duration of use or the type of psychotropic agents, suggesting the need for further studies to clarify these points.

Because the reflux of acidic gastric content into the esophagus leads to symptoms and esophageal mucosal breaks, acid suppression is considered the most effective therapeutic approach, with PPIs being superior to other classes of drug[5]. PPIs are now considered the mainstay of anti-reflux therapy and are extensively prescribed worldwide. This study found that patients with complicated EE were more likely to be prescribed a PPI than those without complications. Considering the previous studies showing that PPI-resistant EE is observed more frequently in patients with severe EE than those with mild EE[23,24], it may be the case that patients with PPI-resistant EE tend to also have complications.

This study also found that moderate alcohol drinking was significantly negatively associated with complicated EE. Although this study did not clarify whether the moderate alcohol drinking was a cause or result of complicated EE, several studies have shown that consumption of large amounts of alcohol can promote regurgitation of acid into the esophagus, thereby causing EE, which is inconsistent with our result[25,26]. Several other studies examining the risk of EE in relation to alcohol consumption have yielded contradictory outcomes. For example, alcohol use has been reported to be a risk factor for EE[27], but its long-term effects and relationship to pathological reflux have not been determined. Other studies, however, have suggested that alcohol exposure was not associated with the risk of EE[28]. EE was recently reported to be significantly associated with psychosocial stress, with the severity of EE correlating with the degree of stress[29]. Moderate amounts of alcohol may reduce psychosocial stress[30], explaining the mechanism underlying the negative relationship between moderate alcohol drinking and complicated EE. Additional physiological studies are necessary to assess the influence of moderate amounts of alcohol on the mechanism of EE in more detail.

Analyzing associated factors with each EE complication separately revealed that aging and severe EE were common associated factors, which is consistent with previous studies[31,32]. In this study we also found that there were more associated factors in esophageal strictures than esophageal ulcer bleeding, indicating that pathophysiology of esophageal strictures was more complex than esophageal ulcer bleeding.

This study had three limitations. First, information about patients’ diets was not recorded, even though chocolate and other high-fat foods have been reported to increase the likelihood of EE[33]. However, the impact of diet on EE was not the focus of this study. Second, this study did not evaluate the rate of drug adherence/compliance[34]. Rather, we focused on characteristics of complicated EE, based on current Japanese clinical guidelines. Further studies will therefore be necessary to clarify these matters. Third, not only body mass index but also upper arm anthropometry and grip strength are important in the assessment of general nutritional status[35]. Because we only evaluated general nutritional status with body mass index, further study is necessary to clarify this matter.

In conclusion, the aging of the Japanese population and increasing levels of stress associated with daily life in modern Japan will likely lead to increased rates of EE and associated complications, despite the availability and widespread use of PPIs.

Masahiro Sakaguchi, Moriguchi Keijinkai Hospital; Nobuo Ueki, Japan Labour Health and Safety Organization, Tokyo Rosai Hospital; Jun Miwa, Toshiba General Hospital; Tomoki Inaba, Kagawa Prefectural Central Hospital; Norimasa Yoshida, Japanese Red Cross Kyoto Daiichi Hospital; Kouichi Sakurai, Hattori Clinic; Masahiro Nakagawa, Hiroshima City Hiroshima Citizens Hospital; Hajime Yamada, Shinko Hospital; Michiya Saito, Michiya Clinic; Kiyoshi Ashida, Rakuwakai Otowa Hospital; Kazuhiro Matsueda, Kurashiki Central Hospital; Hideyuki Hiraishi, Dokkyo Medical University Hospital; Hirokazu Oyamada, Matsushita Memorial Hospital; Takanori Maruo, Japanese Red Cross Osaka Hospital; Nozomu Sugai, KKR Sapporo Medical Center; Kazuhiro Tada, Bell Land General Hospital; Shinichiro Mine, Medical Corporation Kenbikai Sasaki Hospital; Hajime Suzuki, Sapporo Kosei General Hospital; Tomonori Ambo, Hokkaido Cancer Society Asahikawa Cancer Screening Center; Makoto Arai, Chiba University Hospital; Hiroyuki Konishi, Waseda Clinic; Michio Fukushi, Fukushi Medical Clinic; Shyuji Inoue, National Hospital Organization Kochi National Hospital; Tetsuro Hamamoto, Hakuai Hospital; Toshichika Aoki, Aoki Clinic; Haruhiro Yamashita, National Hospital Organization Okayama Medical Center.

Tomoyuki Koike, Tohoku University Hospital; Kazuhiko Nakamura, Kyushu University Hospital; Hirofumi Fujishiro, Shimane Prefectural Central Hospital; Kosei Doi, Dr. Kosei Clinic; Yoshimitsu Okubo, Okubo Clinic; Takahiro Mizutani, Saiseikai Fukuoka General Hospital; Masao Toki, Kyorin University Hospital, Takeshi IchikawaItabashi Chuo Medical Center; Masatsugu Okuyama, Kashiwara Municipal Hospital; Toshifumi Ito, Japan Community Healthcare Organization Osaka Hospital; Takeshi Azuma, Kobe University Hospital; Mitsuru Tokisue, Tokisue Clinic Of Gastroenterological Internal Medicine; Hideyuki Nakase, Nakase Clinic; Yasuhiro Ota, Wajiro Hospital; Shoshi Matsuda, Matsuda Medical Clinic; Toru Maekawa, Maekawa Clinic; Yasuhiko Abe, Yamagata University Hospital; Daisuke Kawai, Tsuyama Chuo Hospital; Yasuyuki Shimoyama, Gunma University Hospital; Yasuo Hanamure, Hanamure Hospital; Hiroto Moriyasu, Minami-Nara General Medical Center; Masanori Ohara, Hakodate National Hospital; Hideki Mizuno, Toyama City Hospital; Naoto Kurihara, Nerima General Hospital; Eijiro Hayashi, Osaka-Central Hospital.

Masayuki Uemura, Kurashiki Daiichi Hospital; Hirohisa Tanimura, Osaka Kaisei Hospital.

Masahito Aimi, Shimane University Faculty of Medicine; Motoyasu Chibai, Heiwadai Clinic.

Kazuhiko Inoue, Central Hospital; Shigeaki Mizuno, Nihon University Itabashi Hospital; Fumihiko Kinekawa, Sanuki Municipal Hospital; Shuji Mizumachi, Mizumachi Medical Clinic; Hiroyuki Okada, Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine; Yoshinori Fujimura, The Sakakibara Heart Institute of Okayama; Nobuaki Yagi, Murakami Memorial Hospital Asahi University; Kunio Kasugai, Aichi Medical University; Hiroko Ishikawa, Medical corporation Kyouseikai Matsuzono 2nd Hospital; Kazuhiro Maeda, Medical Corporation Shin-ai Tenjin Clinic; Ken Ohnita, Nagasaki University Hospital; Akiyoshi Shimatani, Shimatani Clinic; Yoshihisa Urita, Toho University Omori Medical Center; Yoshimi Shibazaki, Ashoro-town National Health Insurancehospital; Noriko Watanabe, Mie Chuo Medical Center; Toshikazu Sekiguchi, Sekiguchi Clinic; Yuichi Sato, Niigata University Medical & Dental Hospital; Daisuke Asaoka, University of Juntendo School of Medicine; Fukunori Kinjo, Urasoe General Hospital; Toshihisa Takeuchi, Osaka Medical College Hospital; Yasuhiro Fujiwara, Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine; Hideyuki Inoue, Kagawa Rosai Hospital; Kazumi Nakamura, Public Nanokaichi Hospital; Yuzuru Toki, Hidaka Hospital; Yuji Amano, Kaken Hospital, International University of Health and Welfare; Nobumi Hisamoto, Junpukai Asahigaoka Hospital; Masahiko Inamori, Yokohama City University Hospital; Masaki Inoue, Special Medical Corpration Jinkokai Hongo Central Hospital; Satoshi Tokioka, First Towakai Hospital; Jun Matsumoto, Kagoshima Takaoka Hospital; Kazumichi Harada, Harada Hospital; Tetsuya Murao, Kumamoto University Hospital; Makoto Hojo, Hojo Clinic; Soji Ozawa, Tokai University School of Medicine; Ryo Yamauchi, Mitsubishi Mihara Hospital.

The prevalence of erosive esophagitis (EE) was previously considered much lower in Asian countries, including Japan, than in Western countries. In recent years, the prevalence of EE has increased in Japan. The major esophageal complications of EE include ulceration, strictures, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Although proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have altered the presentation of complicated EE, little is known about its epidemiology.

The research hotspot is to evaluate the frequency of complicated EE and its associated factors at the time of PPIs availability in real-world clinical settings by the nationwide prospective survey in Japan.

Despite the availability and widespread use of PPIs, EE related complications are likely to remain a problem in Japan. Increased age, concomitant use of psychotropic agents, and severe EE as defined by LA grades B-D were significantly associated with complications, while moderate alcohol consumption showed a significant negative association with complications.

The aging of the Japanese population and increasing levels of stress associated with daily life in modern Japan will likely lead to increased rates of EE and associated complications, despite the availability and widespread use of PPIs.

EE-related complications included esophageal ulcer bleeding, strictures, and perforation. The endoscopic extent of gastric mucosal atrophy was classified by the Kimura-Takemoto classification. Long-segment Barrett’s esophagus was diagnosed by endoscopic identification of columnar epithelium extending more than 3 cm into the esophagus without histological evidence of intestinal metaplasia.

Very interesting topic and some of the data provided appear indicative of EE etiologies. To improve the strength of this paper, a more comprehensive review of the international literature (i.e., grey papers) may provide more compelling data to include in your review process. Further a meta-analysis would have added further credence to your findings.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chang ET, Kruszewski WJ S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu WX

| 1. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Manabe N, Haruma K, Kamada T, Kusunoki H, Inoue K, Murao T, Imamura H, Matsumoto H, Tarumi K, Shiotani A. Changes of upper gastrointestinal symptoms and endoscopic findings in Japan over 25 years. Intern Med. 2011;50:1357-1363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mishima I, Adachi K, Arima N, Amano K, Takashima T, Moritani M, Furuta K, Kinoshita Y. Prevalence of endoscopically negative and positive gastroesophageal reflux disease in the Japanese. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1005-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Orlando RC. Reflux esophagitis. In: Yamada T, editors. Textbook of gastroenterology, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 2005. . |

| 5. | Chiba N, De Gara CJ, Wilkinson JM, Hunt RH. Speed of healing and symptom relief in grade II to IV gastroesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1798-1810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 579] [Cited by in RCA: 547] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bruley des Varannes S, Coron E, Galmiche JP. Short and long-term PPI treatment for GERD. Do we need more-potent anti-secretory drugs? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:905-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1518] [Cited by in RCA: 1653] [Article Influence: 63.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 1969;3:87-97. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 612] [Cited by in RCA: 743] [Article Influence: 43.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 9. | Chiba H, Gunji T, Sato H, Iijima K, Fujibayashi K, Okumura M, Sasabe N, Matsuhashi N, Nakajima A. A cross-sectional study on the risk factors for erosive esophagitis in young adults. Intern Med. 2012;51:1293-1299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gunji T, Sato H, Iijima K, Fujibayashi K, Okumura M, Sasabe N, Urabe A, Matsuhashi N. Risk factors for erosive esophagitis: a cross-sectional study of a large number of Japanese males. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:448-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang FW, Tu MS, Chuang HY, Yu HC, Cheng LC, Hsu PI. Erosive esophagitis in asymptomatic subjects: risk factors. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1320-1324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nocon M, Labenz J, Willich SN. Lifestyle factors and symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux -- a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:169-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dore MP, Maragkoudakis E, Fraley K, Pedroni A, Tadeu V, Realdi G, Graham DY, Delitala G, Malaty HM. Diet, lifestyle and gender in gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2027-2032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Singh S, Sharma AN, Murad MH, Buttar NS, El-Serag HB, Katzka DA, Iyer PG. Central adiposity is associated with increased risk of esophageal inflammation, metaplasia, and adenocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1399-1412.e7. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Cai N, Ji GZ, Fan ZN, Wu YF, Zhang FM, Zhao ZF, Xu W, Liu Z. Association between body mass index and erosive esophagitis: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2545-2553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Corley DA, Kubo A. Body mass index and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2619-2628. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Greenwald DA. Aging, the gastrointestinal tract, and risk of acid-related disease. Am J Med. 2004;117 Suppl 5A:8S-13S. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Lee J, Anggiansah A, Anggiansah R, Young A, Wong T, Fox M. Effects of age on the gastroesophageal junction, esophageal motility, and reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1392-1398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Menon S, Trudgill N. Risk factors in the aetiology of hiatus hernia: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:133-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Maddalena AS, Fox M, Hofmann M, Hock C. Esophageal dysfunction on psychotropic medication. A case report and literature review. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2004;37:134-138. [PubMed] |

| 21. | van Soest EM, Dieleman JP, Siersema PD, Schoof L, Sturkenboom MC, Kuipers EJ. Tricyclic antidepressants and the risk of reflux esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1870-1877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Martín-Merino E, Ruigómez A, García Rodríguez LA, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Depression and treatment with antidepressants are associated with the development of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:1132-1140. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Watanabe A, Iwakiri R, Yamaguchi D, Higuchi T, Tsuruoka N, Miyahara K, Akutagawa K, Sakata Y, Fujise T, Oda Y. Risk factors for resistance to proton pump inhibitor maintenance therapy for reflux esophagitis in Japanese women over 60 years. Digestion. 2012;86:323-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Richter JE, Kahrilas PJ, Johanson J, Maton P, Breiter JR, Hwang C, Marino V, Hamelin B, Levine JG. Efficacy and safety of esomeprazole compared with omeprazole in GERD patients with erosive esophagitis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:656-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Boguradzka A, Tarnowski W, Cabaj H. Gastroesophageal reflux in alcohol-abusing patients. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2011;121:230-236. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Piqué N, Ponce M, Garrigues V, Rodrigo L, Calvo F, de Argila CM, Borda F, Naranjo A, Alcedo J, José Soria M. Prevalence of severe esophagitis in Spain. Results of the PRESS study (Prevalence and Risk factors for Esophagitis in Spain: A cross-sectional study). United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:229-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Watanabe Y, Fujiwara Y, Shiba M, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Oshitani N, Matsumoto T, Nishikawa H, Higuchi K, Arakawa T. Cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in Japanese men. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:807-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Nilsson M, Johnsen R, Ye W, Hveem K, Lagergren J. Lifestyle related risk factors in the aetiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux. Gut. 2004;53:1730-1735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Song EM, Jung HK, Jung JM. The association between reflux esophagitis and psychosocial stress. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:471-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Turner TB, Bennett VL, Hernandez H. The beneficial side of moderate alcohol use. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1981;148:53-63. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Pisegna J, Holtmann G, Howden CW, Katelaris PH, Sharma P, Spechler S, Triadafilopoulos G, Tytgat G. Review article: oesophageal complications and consequences of persistent gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 Suppl 9:47-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Belhocine K, Galmiche JP. Epidemiology of the complications of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis. 2009;27:7-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Festi D, Scaioli E, Baldi F, Vestito A, Pasqui F, Di Biase AR, Colecchia A. Body weight, lifestyle, dietary habits and gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1690-1701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Grey MR. Maintenance therapies for reflux esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:600-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Bowrey DJ, Baker M, Halliday V, Thomas AL, Pulikottil-Jacob R, Smith K, Morris T, Ring A. A randomised controlled trial of six weeks of home enteral nutrition versus standard care after oesophagectomy or total gastrectomy for cancer: report on a pilot and feasibility study. Trials. 2015;16:531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |