Published online May 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i19.3513

Peer-review started: December 16, 2016

First decision: January 10, 2017

Revised: February 12, 2017

Accepted: March 31, 2017

Article in press: March 31, 2017

Published online: May 21, 2017

Processing time: 157 Days and 2.1 Hours

To investigate the relationship between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use and the subsequent development of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

This retrospective, observational, population-based cohort study collected data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database. A total of 19653 patients newly using SSRIs and 78612 patients not using SSRIs, matched by age and sex at a ratio of 1:4, were enrolled in the study from January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2010. The patients were followed until IBS diagnosis, withdrawal from the National Health Insurance system, or the end of 2011. We analyzed the effects of SSRIs on the risk of subsequent IBS using Cox proportional hazards regression models.

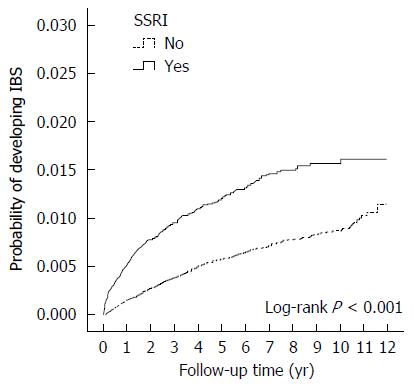

A total of 236 patients in the SSRI cohort (incidence, 2.17/1000 person-years) and 478 patients in the comparison cohort (incidence, 1.04/1000 person-years) received a new diagnosis of IBS. The mean follow-up period from SSRI exposure to IBS diagnosis was 2.05 years. The incidence of IBS increased with advancing age. Patients with anxiety disorders had a significantly increased adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of IBS (aHR = 1.33, 95%CI: 1.11-1.59, P = 0.002). After adjusting for sex, age, urbanization, family income, area of residence, occupation, the use of anti-psychotics and other comorbidities, the overall aHR in the SSRI cohort compared with that in the comparison cohort was 1.74 (95%CI: 1.44-2.10; P < 0.001). The cumulative incidence of IBS was higher in the SSRI cohort than in the non-SSRI cohort (log-rank test, P < 0.001).

SSRI users show an increased risk of subsequent diagnosis of IBS in Taiwan.

Core tip: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) users were associated with a risk of subsequently diagnosed irritable bowel syndrome. The brain-gut axis may play a key role in this relationship. In clinical practice, physicians should pay attention to the gastrointestinal symptoms of patients with psychiatric disorders and SSRI use.

- Citation: Lin WT, Liao YJ, Peng YC, Chang CH, Lin CH, Yeh HZ, Chang CS. Relationship between use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and irritable bowel syndrome: A population-based cohort study. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(19): 3513-3521

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i19/3513.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i19.3513

Antidepressants are among the most widely used medications in clinical practice for the treatment of depressive disorder, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and numerous other psychiatric diseases[1,2]. Among the many classes of antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most commonly prescribed because of their effectiveness in treating many psychiatric disorders. SSRIs are safer and have a more favorable side-effect profile than the previous generations of antidepressants[3]. However, numerous studies have indicated that short-term use of SSRIs can cause many adverse side effects, including nausea, diarrhea and unstable mood swings. Additionally, suicide attempts, gastrointestinal bleeding, sexual dysfunction, and hyponatremia may occur during long-term use[4-6].

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is part of a large group of functional gastrointestinal disorders that are characterized by recurrent abdominal discomfort or pain and disturbed defecation in the absence of organic disease[7,8]. IBS is one of the most commonly treated diseases by primary care physicians as well as gastroenterologists. The prevalence of IBS is estimated to be 7.5%-21% worldwide[9,10]. IBS is a functional disorder and has no contribution towards mortality[11]; however, it is chronic and significantly reduces patients’ quality of life[9,12,13]. The suggested treatments for IBS include antispasmodics, antidiarrheal agents, laxatives, prokinetics, probiotics, anxiolytics, SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), 5-HT3 antagonists, cGMA agonists, and antibiotics according to each patient’s clinical symptoms[14,15]. However, there is no universally accepted or recommended therapy that effectively cures this disease.

The pathophysiology of IBS is believed to be associated with abnormal gastrointestinal motility, visceral hypersensitivity, low-grade inflammation, stress and brain-gut interactions[9,16]. Additionally, a high prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with IBS, in particular anxiety and depressive disorders, has been reported in previous studies[16,17]. Antidepressants are often used to treat a variety of functional bowel disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants have been proven to offer statistically significant control of IBS symptoms in a previous meta-analysis[18,19]. Additionally, several randomized controlled trials have evaluated the safety and efficacy of fluoxetine, citalopram and paroxetine for the treatment of IBS[20-23]. However, the evidence regarding the effectiveness of SSRIs in providing symptom relief in IBS is inconsistent. The American Gastroenterological Association Institute guidelines advise against using SSRIs for patients with IBS, based on the lack of improvement in global relief of symptoms identified in pooled estimates of five randomized control trials[24].

The present study aimed to explore the relationship of SSRIs with the subsequent development of IBS using the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD).

The database used in our study was the NHIRD of Taiwan. The National Health Insurance (NHI) program in Taiwan was initiated in 1995 and enrolled over 24 million people by the end of 2014, representing 99% of the population in Taiwan. In the present study, data from the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database (LHID) 2000 were analyzed. The LHID 2000 is a subset of the NHIRD that contains data from 1000000 randomly sampled patients, which is approximately 5% of the Taiwan’s general population. We conducted a retrospective observational study on the correlation of SSRIs with and their possible influence on IBS. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Taichung Veterans General Hospital (IRB number: CE13152B-3), and because the data were obtained from the LHID 2000, informed consent from the participants was not obtained. The IRB specifically waived the requirement for consent.

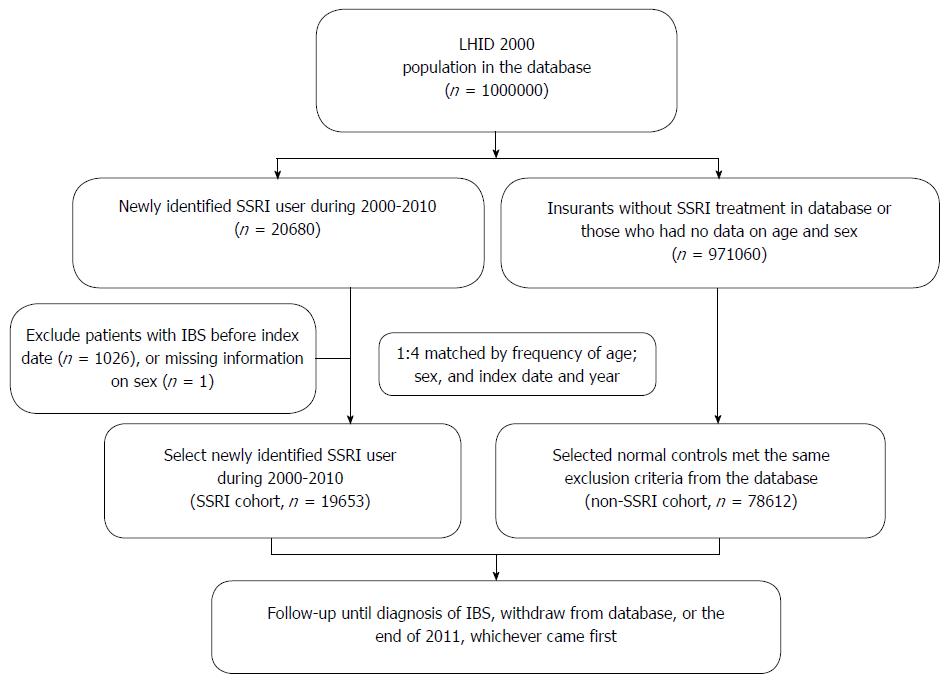

We extracted data from the LHID 2000 for this retrospective study. Patients with a more than two-month medical prescription for an SSRI during one year between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2010 were selected. The prescribed SSRIs included fluoxetine, citalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, fluvoxamine and escitalopram. We excluded any patients who were diagnosed with IBS (ICD-9-CM code: 564.1) prior to medical treatment with SSRIs. The comparison cohort included patients without any medical history of SSRI use who were frequency-matched with the SSRI cohort by age, sex, index date and year at a ratio of 1:4 (Figure 1). To ensure the validity of the diagnosis, we included only patients who were diagnosed with IBS (ICD-9-CM code: 564.1) in more than three outpatient visits or more than one inpatient hospitalization. The included patients taking SSRIs were regularly followed at the database for at least three outpatient visits. Thus, we supposed that these patients needed these medication, and had compliance in medication.

In addition, patients with inflammatory bowel disease (ICD-9:555, 556) were excluded because some of these patients exhibit symptoms similar to those of IBS during the inactive or remission stage of inflammatory bowel syndrome[25-29]. Additionally, patients with a diagnosis of infectious enterocolitis (ICD 9: 0078,0079, 0080-0088, 0090-0093, 558, 0030, 0062, 11285) within three months prior to the diagnosis of IBS were excluded due to the potentially increased risk of post-infectious IBS associated with bacterial, protozoan, helminth, or viral infections, all of which have been reported[30-34]. The main outcome was the incidence of newly diagnosed IBS during the follow-up period, which was estimated as the duration from the index date until IBS, withdrawal from the insurance system, or the end of study in 2011.

Furthermore, common comorbidities diagnosed before enrollment in this study, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, colorectal cancer, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, and posttraumatic disorder, were compared between the SSRI and comparison cohorts.

All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States). The distributions of SSRI exposure based on subject’s age, gender and clinical comorbidities were examined using χ2 tests for categorical variables.

In the cohort study, multivariable Cox proportional hazard models were used to explore the relationship between exposure to SSRI and the diagnosis of IBS, after adjusting for age, gender and medical comorbidities. All statistical tests were two-sided, conducted at a significance level of 0.05, and reported using P values and/or 95%CIs.

The eligible study participants included 19653 patients in the SSRI cohort and 78612 persons in the comparison cohort, with a similar age and sex distribution (Figure 1 and Table 1). Males represented 41.5% and females 58.5% of the entire study population. The mean follow-up time in the present study was 5.9 ± 3.0 years in the non-SSRI cohort and 5.5 ± 3.2 years in the SSRI cohort. The mean follow-up period of SSRI exposure to IBS diagnosis was 2.05 years. The majority of psychiatric disorders leading to a prescription of SSRI included anxiety (48.2%) and major depressive disorders (21.8%). There was more concomitant anti-psychotic usage in the SSRI cohort than in the non-SSRI group. However, most participants in both groups did not use anti-psychotics.

| Variable | SSRI use | P value | |

| No (n = 78612) | Yes (n = 19653) | ||

| Sex | 1.000 | ||

| Female | 45984 (58.5) | 11496 (58.5) | |

| Male | 32628 (41.5) | 8157 (41.5) | |

| Age, yr | 1.000 | ||

| < 20 | 5548 (7.1) | 1387 (7.1) | |

| 20-29 | 11592 (14.8) | 2898 (14.8) | |

| 30-39 | 14312 (18.2) | 3578 (18.2) | |

| 40-49 | 15112 (19.2) | 3778 (19.2) | |

| 50-59 | 11720 (14.9) | 2930 (14.9) | |

| ≥ 60 | 20328 (25.9) | 5082 (25.9) | |

| Urbanization1 | < 0.001 | ||

| 1 | 24102 (31.3) | 6275 (32.7) | |

| 2 | 23134 (30.0) | 5851 (30.5) | |

| 3 | 12486 (16.2) | 2827 (14.7) | |

| 4 | 17325 (22.5) | 4228 (22.0) | |

| Family income (NTD) | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 13932 (17.7) | 3411 (17.4) | |

| 1-15840 | 14871 (18.9) | 4807 (24.5) | |

| 15841-28800 | 33687 (42.9) | 7915 (40.3) | |

| 28801-45800 | 10243 (13.0) | 2173 (11.1) | |

| ≥ 45801 | 5874 (7.5) | 1346 (6.9) | |

| Area | < 0.001 | ||

| North | 39708 (50.6) | 10001 (51.0) | |

| Midland | 14067 (17.9) | 3265 (16.7) | |

| South | 22823 (29.1) | 5642 (28.8) | |

| East | 1837 (2.3) | 690 (3.5) | |

| Occupation | < 0.001 | ||

| Public and military | 5735 (8.2) | 1531 (8.8) | |

| Industry | 23168 (33.3) | 5617 (32.3) | |

| Business | 28266 (40.6) | 5841 (33.6) | |

| Low income | 559 (0.8) | 385 (2.2) | |

| Other and retired | 11898 (17.1) | 3994 (23.0) | |

| Anti-psychotics | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 75615 (96.2) | 16022 (81.5) | |

| Yes | 2997 (3.8) | 3631 (18.5) | |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 8126 (10.3) | 3143 (16.0) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 18319 (23.3) | 6726 (34.2) | < 0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 11823 (15.0) | 4521 (23.0) | < 0.001 |

| Colorectal cancer | 290 (0.4) | 96 (0.5) | 0.017 |

| Major depressive disorder | 770 (0.98) | 4274 (21.8) | < 0.001 |

| Anxiety disorder | 10007 (12.7) | 9477 (48.2) | < 0.001 |

| Bipolar disorder | 130 (0.2) | 273 (1.4) | < 0.001 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 7 (0.0) | 101 (0.5) | < 0.001 |

| Eating disorder | 26 (0.0) | 141 (0.7) | < 0.001 |

| Mean follow-up time (yr) | 5.86 ± 3.00 | 5.53 ± 3.21 | |

At the baseline, comorbid diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, colorectal cancer, major depressive disorder and anxiety disorder were more prevalent in the SSRI cohort than in the comparison cohort.

A total of 236 patients in the SSRI cohort (incidence, 2.17/1000 person-years) and 478 patients in the comparison cohort (incidence, 1.04/1000 person-years) had a new diagnosis of IBS during the follow-up period (Table 2). The incidence of IBS increased with advancing age. Comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, colorectal cancer, and major depressive disorder did not influence the HR of IBS. However, patients with anxiety disorders had a significantly increased HR of IBS (HR = 1.33, 95%CI: 1.11-1.59, P = 0.002). The use of anti-psychotics did not affect the incidence of IBS, whereas the use of SSRIs was associated with an increased HR of IBS.

| Variable | Events | PT | Rate1 | HR2 | (95%CI) | P value |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 414 | 335363 | 1.23 | 1.00 | (reference) | |

| Male | 300 | 233656 | 1.28 | 1.05 | (0.91-1.23) | 0.495 |

| Age, yr | ||||||

| < 20 | 13 | 43139 | 0.30 | 1.00 | (reference) | |

| 20-29 | 47 | 91408 | 0.51 | 1.62 | (0.87-3.01) | 0.128 |

| 30-39 | 93 | 110721 | 0.84 | 2.52 | (1.40-4.55) | 0.002 |

| 40-49 | 153 | 113198 | 1.35 | 3.94 | (2.22-7.02) | < 0.001 |

| 50-59 | 133 | 80752 | 1.65 | 4.56 | (2.54-8.17) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 60 | 275 | 129801 | 2.12 | 5.57 | (3.12-9.92) | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidity (yes vs no) | ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 113 | 55858 | 2.02 | 0.93 | (0.74-1.17) | 0.549 |

| Hypertension | 269 | 129073 | 2.08 | 1.06 | (0.87-1.28) | 0.576 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 175 | 84352 | 2.07 | 1.07 | (0.88-1.31) | 0.482 |

| Colorectal cancer | 5 | 1527 | 3.27 | 1.48 | (0.61-3.58) | 0.386 |

| Major depressive disorder | 67 | 30292 | 2.21 | 1.19 | (0.90-1.57) | 0.217 |

| Anxiety disorder | 220 | 96735 | 2.27 | 1.33 | (1.11-1.59) | 0.002 |

| Bipolar disorder | 5 | 2435 | 2.05 | 1.03 | (0.42-2.52) | 0.820 |

| Anti-psychotics | ||||||

| No | 630 | 535264 | 1.18 | 1.00 | (reference) | |

| Yes | 84 | 33755 | 2.49 | 1.18 | (0.92-1.50) | 0.193 |

| SSRIs | ||||||

| No | 478 | 460307 | 1.04 | 1.00 | (reference) | |

| Yes | 236 | 108713 | 2.17 | 1.74 | (1.44-2.10) | < 0.001 |

After adjusting for sex, age and other comorbidities including diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and colorectal cancer, the overall adjusted HR (aHR) in the SSRI cohort compared with the comparison cohort was 1.74 (95%CI: 1.44-2.10; P < 0.001) using Cox regression analysis. The subgroup analysis showed that the aHR was higher in SSRI users than in non-SSRI users among females (aHR = 1.65; 95%CI: 1.29-2.11), males (aHR = 1.85; 95%CI: 1.38-2.48) and individuals aged between 20 and 60 years (Table 3).

| SSRI use (2000-2010) | aHR2 | (95%CI) | P value | ||||||

| No (n = 78612) | Yes (n = 19653) | ||||||||

| Event | Person-years | Incidence rate of IBS1 | Event | Person-years | Incidence rate of IBS | ||||

| Overall | 478 | 460307 | 1.04 | 236 | 108713 | 2.17 | 1.74 | (1.44-2.10) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 282 | 270195 | 1.04 | 132 | 65169 | 2.03 | 1.65 | (1.29-2.11) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 196 | 190112 | 1.03 | 104 | 43544 | 2.39 | 1.85 | (1.38-2.48) | < 0.001 |

| Age | |||||||||

| < 20 | 8 | 34575 | 0.23 | 5 | 8564 | 0.58 | 1.12 | (0.23-5.41) | 0.884 |

| 20-29 | 27 | 73594 | 0.37 | 20 | 17815 | 1.12 | 2.78 | (1.36-5.70) | 0.005 |

| 30-39 | 61 | 89305 | 0.68 | 32 | 21416 | 1.49 | 1.95 | (1.13-3.34) | 0.016 |

| 40-49 | 96 | 91299 | 1.05 | 57 | 21899 | 2.60 | 1.79 | (1.19-2.69) | 0.005 |

| 50-59 | 85 | 65244 | 1.30 | 48 | 15508 | 3.10 | 2.17 | (1.40-3.36) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 60 | 201 | 106290 | 1.89 | 74 | 23511 | 3.15 | 1.32 | (0.97-1.79) | 0.077 |

The cumulative incidence of IBS was higher in the SSRI cohort than in the non-SSRI cohort (log-rank test, P < 0.001) (Figure 2).

Table 4 shows the association between SSRI exposure days over one year and the HR of a subsequent diagnosis of IBS. The aHR was highest in individuals with a one-year SSRI exposure of less than 90 d (aHR = 3.27, 95%CI: 2.61-4.08). The aHR remained significantly higher in patients with longer durations of SSRI exposure.

| aHR1 | (95%CI) | P value | |

| SSRI non-users | 1.00 | (reference) | |

| SSRI exposure < 90 d | 3.27 | (2.61-4.08) | < 0.001 |

| SSRI exposure 90-180 d | 1.38 | (1.03-1.85) | 0.029 |

| SSRI exposure 181-270 d | 1.49 | (1.05-2.13) | 0.027 |

| SSRI exposure ≥ 270 d | 1.52 | (1.07-2.15) | 0.020 |

A subgroup analysis of SSRI and non-SSRI users showed a significantly increased aHR of IBS in SSRI only users (aHR = 1.82, 95%CI: 1.50-2.21, P < 0.001) but not in the users of other antidepressants only (aHR = 1.33, 95%CI: 0.75-2.36, P = 0.338) or the combined SSRI and other antidepressant users (aHR = 1.30, 95%CI: 0.84-2.01, P = 0.235) (Table 5).

| n | aHR1 | (95%CI) | P value | |

| Overall | ||||

| Non-SSRIs | 77327 | 1.00 | (reference) | |

| Non-SSRIs + other antidepressants | 1285 | 1.33 | (0.75-2.36) | 0.338 |

| SSRIs + other antidepressants | 2872 | 1.30 | (0.84-2.01) | 0.235 |

| SSRIs only | 16781 | 1.82 | (1.50-2.21) | < 0.001 |

Based on our review of the literature, this is the first study using nationwide population database to investigate the relationship between SSRI prescriptions and IBS in Taiwan. Our results revealed that patients exposed to SSRIs had an increased risk of developing IBS (aHR = 1.74) after adjusting for sex, age, and major comorbidities.

In this study, we demonstrated that IBS in SSRI users tended to occur in older patients. The incidence of IBS became higher as age increased in both SSRI users and non-users, and this finding conflict with both the global data and a previous questionnaire survey conducted in Taiwan[10,35]. A previous global meta-analysis and questionnaire study in Taiwan showed that the prevalence of IBS decreased with advancing age. However, the participants in the previous questionnaire study in Taiwan were healthy volunteers, and thus the prevalence of IBS in the Taiwan’s general population may have been underestimated. Additionally, IBS symptoms may occur at early ages with relatively benign symptoms. Most patients may tolerate these symptoms and not seek medical advice; this tendency may have also led to an underestimation of the incidence of IBS in young individuals.

To evaluate the dose effect of SSRIs on the subsequent development of IBS, we analyzed the days of SSRI exposure within one year and determined the HR of subsequent IBS diagnosis. The aHR was highest in individuals with SSRI exposure for less than 90 d but remained significantly higher for patients with longer exposure times. Although SSRIs include widely used antidepressants that are more tolerable and have relatively benign adverse effects compared to TCAs or monoamine oxidase inhibitors[3], they continue to have some early onset adverse effects and problems associated with long-term treatment. The early onset adverse effects include gastrointestinal discomfort, nausea, dyspepsia and diarrhea and disappear within two to three weeks[5]. The higher HR of IBS in individuals with lower SSRI exposure times may be due to these early onset gastrointestinal side effects that lead to misdiagnosis of IBS by clinical physicians. However, Table 4 shows that patients with SSRI exposure for more than 90 d had a significantly higher HR of IBS, and this finding cannot be explained by the early gastrointestinal adverse effects of SSRIs. In addition, the mean follow-up time from SSRI exposure to IBS diagnosis was 2.05 years, which is long enough to exclude transient adverse effects of SSRIs. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that the long duration of psychiatric disorders leads to an increased risk of subsequent IBS.

Many studies have identified a relationship between IBS and psychiatric disorders[17,36]. In patients with IBS who seek treatment, the rates of comorbid psychiatric disorders range from 54% to 94%[9,12]. Anxiety and depression disorders are associated with gastrointestinal symptoms in accordance with brain-gut interactions[37-40]. Additionally, the communication between the central nervous system and enteric nervous system appears to be bidirectional[36]. The biopsychological model of IBS suggests that deterioration of gastrointestinal symptoms could exacerbate anxiety and depression (bottom-up model) and that psychological factors themselves similarly influenced physiological factors (top-down model)[41]. Fond et al[17] demonstrated in a systematic review and meta-analysis that patients with IBS have significantly higher levels of anxiety and depression than healthy controls. To exclude the influence of other antidepressants, we performed a subgroup analysis of SSRI and non-SSRI users. Table 5 shows that the aHR was significantly higher in the users of SSRIs only compared with the users of non-SSRIs or users of combined SSRIs and other antidepressants. The use of other antidepressants only or in combination with SSRIs was not associated with an increased risk of IBS.

One possible reason for the higher incidence of IBS in the SSRI cohort is that the patients’ underlying psychiatric disorders, particularly anxiety, may have deteriorated and thus their subclinical gastrointestinal symptoms became overt. Under these conditions, clinical physicians may provide new prescriptions for SSRIs, and patients may seek medical advice for IBS symptoms. This process is consistent with our study results, which showed that patients with anxiety disorders had a significantly higher HR of IBS. Poorly controlled anxiety disorders and unstable mood may exacerbate the symptoms of IBS. The increased HR of IBS in the SSRI cohort, compared with the comparison cohort in our study, may be due to the increased severity of anxiety disorders, poor compliance to SSRIs due to adverse medication effects or personal reasons.

There were some limitations to our study. First, there is only one code for IBS (ICD-9-CM code: 564.1) in the ICD-9 system, and further subgroup analyses were therefore not feasible. Second, data on lifestyle factors, such as smoking and alcohol use, were not available in the NHIRD. Third, information on drug compliance was not obtained from this health care database. Fourth, the severity of any psychiatric disorder upon enrollment in the study was also not available in the NHIRD. Fifth, there are always coding issues in database studies. There may be registration differences among the physicians and psychiatrists who did not code for IBS and the gastroenterologists who did not code for depression/anxiety. However, most physicians should adhere to the proper coding standards due to NHI payment rules.

In conclusion, SSRI use is associated with subsequently diagnosed IBS. In clinical practice, it is important to pay attention to the gastrointestinal symptoms of patients with psychiatric disorders who use SSRIs.

We thank the National Health Research Institute and the Bureau of National Health Insurance for providing the data for this study.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is part of a large group of functional gastrointestinal disorders that significantly reduce patients’ quality of life. Antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in particular, have been used to treat refractory IBS. The influence of SSRIs on the subsequent development of IBS remains unknown.

The results regarding the clinical efficacy of SSRI in treating IBS are inconsistent. This study presents the first attempt to elucidate the relationship between SSRI use and subsequent diagnosis of IBS.

The overall adjusted hazard ratio was higher in the SSRI cohort than in the comparison cohort. The incidence of IBS in SSRI users increased with advancing age.

Physicians in clinical practice should pay attention to the gastrointestinal symptoms of patients with psychiatric disorders and SSRI use.

IBS is characterized by recurrent abdominal discomfort or pain and disturbed defecation in the absence of an organic disease.

This study by Lin et al probes the relationship between SSRI use and the subsequent diagnosis of IBS over a 10-year span, using a national health insurance research database. The data indicate an adjusted increase in HR of 1.74 (P = 0.002) for the diagnosis of IBS in patients treated with SSRIs.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Rhoads JM S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Ables AZ, Baughman OL. Antidepressants: update on new agents and indications. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:547-554. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Masand PS, Gupta S. Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors: an update. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1999;7:69-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Brambilla P, Cipriani A, Hotopf M, Barbui C. Side-effect profile of fluoxetine in comparison with other SSRIs, tricyclic and newer antidepressants: a meta-analysis of clinical trial data. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2005;38:69-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nierenberg AA, Ostacher MJ, Huffman JC, Ametrano RM, Fava M, Perlis RH. A brief review of antidepressant efficacy, effectiveness, indications, and usage for major depressive disorder. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:428-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moret C, Isaac M, Briley M. Problems associated with long-term treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23:967-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Spigset O. Adverse reactions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: reports from a spontaneous reporting system. Drug Saf. 1999;20:277-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Longstreth G, Thompson W, Chey W, Houghton L, Mearin F, Spiller R. Rome III: the functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. Functional bowel disorders 2006: 487-555. . |

| 8. | Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, Soffer EE, Spiegel BM, Quigley EM. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109 Suppl 1:S2-S26; quiz S27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 403] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108-2131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 933] [Cited by in RCA: 950] [Article Influence: 41.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:712-721.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1412] [Article Influence: 108.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Canavan C, West J, Card T. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:71-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 407] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1140-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 775] [Cited by in RCA: 774] [Article Influence: 33.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Canavan C, West J, Card T. Review article: the economic impact of the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1023-1034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 29.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chang L, Lembo A, Sultan S. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Technical Review on the pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1149-1172.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Gwee KA, Bak YT, Ghoshal UC, Gonlachanvit S, Lee OY, Fock KM, Chua AS, Lu CL, Goh KL, Kositchaiwat C. Asian consensus on irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1189-1205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Talley NJ, Spiller R. Irritable bowel syndrome: a little understood organic bowel disease? Lancet. 2002;360:555-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fond G, Loundou A, Hamdani N, Boukouaci W, Dargel A, Oliveira J, Roger M, Tamouza R, Leboyer M, Boyer L. Anxiety and depression comorbidities in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264:651-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 474] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Rezaie A, Abdollahi M. Efficacy of tricyclic antidepressants in irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1548-1553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Xie C, Tang Y, Wang Y, Yu T, Wang Y, Jiang L, Lin L. Efficacy and Safety of Antidepressants for the Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Creed F, Fernandes L, Guthrie E, Palmer S, Ratcliffe J, Read N, Rigby C, Thompson D, Tomenson B. The cost-effectiveness of psychotherapy and paroxetine for severe irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:303-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Ladabaum U, Sharabidze A, Levin TR, Zhao WK, Chung E, Bacchetti P, Jin C, Grimes B, Pepin CJ. Citalopram provides little or no benefit in nondepressed patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:42-48.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kuiken SD, Tytgat GN, Boeckxstaens GE. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine does not change rectal sensitivity and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:219-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tack J, Broekaert D, Fischler B, Van Oudenhove L, Gevers AM, Janssens J. A controlled crossover study of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2006;55:1095-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Weinberg DS, Smalley W, Heidelbaugh JJ, Sultan S. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1146-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bayless TM, Harris ML. Inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Med Clin North Am. 1990;74:21-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Annese V, Bassotti G, Napolitano G, Usai P, Andriulli A, Vantrappen G. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in patients with inactive Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:1107-1117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pezzone MA, Wald A. Functional bowel disorders in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31:347-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ginsburg PM, Bayless TM. Managing Functional Disturbances in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2005;8:211-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Isgar B, Harman M, Kaye MD, Whorwell PJ. Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in ulcerative colitis in remission. Gut. 1983;24:190-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Wang LH, Fang XC, Pan GZ. Bacillary dysentery as a causative factor of irritable bowel syndrome and its pathogenesis. Gut. 2004;53:1096-1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Marshall JK, Thabane M, Garg AX, Clark WF, Salvadori M, Collins SM. Incidence and epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome after a large waterborne outbreak of bacterial dysentery. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:445-450; quiz 660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zanini B, Ricci C, Bandera F, Caselani F, Magni A, Laronga AM, Lanzini A. Incidence of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome and functional intestinal disorders following a water-borne viral gastroenteritis outbreak. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:891-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Dizdar V, Gilja OH, Hausken T. Increased visceral sensitivity in Giardia-induced postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia. Effect of the 5HT3-antagonist ondansetron. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:977-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hanevik K, Wensaas KA, Rortveit G, Eide GE, Mørch K, Langeland N. Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic fatigue 6 years after giardia infection: a controlled prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:1394-1400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lu CL, Chen CY, Lang HC, Luo JC, Wang SS, Chang FY, Lee SD. Current patterns of irritable bowel syndrome in Taiwan: the Rome II questionnaire on a Chinese population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:1159-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Fadgyas-Stanculete M, Buga AM, Popa-Wagner A, Dumitrascu DL. The relationship between irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric disorders: from molecular changes to clinical manifestations. J Mol Psychiatry. 2014;2:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Fioramonti J, Bueno L. Centrally acting agents and visceral sensitivity. Gut. 2002;51 Suppl 1:i91-i95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Clarke G. Irritable bowel syndrome: a microbiome-gut-brain axis disorder? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14105-14125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 39. | Gunter WD, Shepard JD, Foreman RD, Myers DA, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B. Evidence for visceral hypersensitivity in high-anxiety rats. Physiol Behav. 2000;69:379-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Accarino AM, Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR. Attention and distraction: effects on gut perception. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:415-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Stasi C, Rosselli M, Bellini M, Laffi G, Milani S. Altered neuro-endocrine-immune pathways in the irritable bowel syndrome: the top-down and the bottom-up model. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1177-1185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |