Published online May 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i18.3287

Peer-review started: January 27, 2017

First decision: February 23, 2017

Revised: March 11, 2017

Accepted: April 21, 2017

Article in press: April 21, 2017

Published online: May 14, 2017

Processing time: 112 Days and 0.3 Hours

To study Barrett’s esophagus (BE) in cirrhosis and assess progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) compared to non-cirrhotic BE controls.

Cirrhotic patients who were found to have endoscopic evidence of BE confirmed by the presence of intestinal metaplasia on histology from 1/1/2000 to 12/1/2015 at Cleveland Clinic were included. Cirrhotic patients were matched 1:4 to BE controls without cirrhosis. Age, gender, race, BE length, hiatal hernia size, Child-Pugh (CP) class and histological findings were recorded. Cases and controls without high-grade dysplasia (HGD)/EAC and who had follow-up endoscopies were studied for incidence of dysplasia/EAC and to assess progression rates. Univariable conditional logistic regression was done to assess differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups.

A total of 57 patients with cirrhosis and BE were matched with 228 controls (BE without cirrhosis). The prevalence of dysplasia in cirrhosis and controls were similar with 8.8% vs 12% with low grade dysplasia (LGD) and 12.3 % vs 19.7% with HGD or EAC (P = 0.1). In the incidence cohort of 44 patients with median follow-up time of 2.7 years [interquartile range 1.0, 4.8], there were 7 cases of LGD, 2 cases of HGD, and 2 cases of EAC. There were no differences in incidence rates of HGD/EAC in nondysplastic BE between cirrhotic cases and noncirrhotic controls (1.4 vs 1.1 per 100 person- years, P = 0.8). In LGD, cirrhotic patients were found to have higher rates of progression to HGD/EAC compared to control group though this did not reach statistical significance (13.7 vs 8.1 per 100 person- years, P = 0.51). A significant association was found between a higher CP class and neoplastic progression of BE in cirrhotic patients (HR =7.9, 95%CI: 2.0-30.9, P = 0.003).

Cirrhotics with worsening liver function are at increased risk of progression of BE. More frequent endoscopic surveillance might be warranted in such patients.

Core tip: Fifty seven cirrhotic patients with Barrett’s esophagus (BE) were compared to 228 non-cirrhotic BE controls. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis or cardiac cirrhosis was the most common causes of cirrhosis in this group. There were no differences in incidence rates of high-grade dysplasia (HGD)/esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) in nondysplastic BE between cirrhotic cases and noncirrhotic controls (1.4 vs 1.1 per 100 person -years, P = 0.8). In low grade dysplasia, cirrhotic patients were found to have higher rates of progression to HGD/EAC compared to control group though this did not reach statistical significance (13.7 vs 8.1 per 100 person- years, P = 0.51). There was approximately 8 times increased risk of progression for every one point increase in Child- Pugh class.

- Citation: Apfel T, Lopez R, Sanaka MR, Thota PN. Risk of progression of Barrett's esophagus in patients with cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(18): 3287-3294

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i18/3287.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i18.3287

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a widely prevalent disorder with up to 7% of general population having daily symptoms[1]. However, the prevalence of GERD in patients with liver cirrhosis is much higher with estimates ranging from approximately 37[2] to 64%[3]. This is thought to be due to several factors such as esophageal motor abnormalities from varices leading to reduced esophageal acid clearance[4] and the mechanical effect from ascites which increases intra-abdominal pressure thereby contributing to reflux[5]. Additionally, worsening liver function in cirrhotic patients seems to be associated with increased prevalence of GERD[6-8]. This may be due to elevated levels of hormones such as vasoactive intestinal peptide, neurotensin and nitrous oxide in cirrhosis which reduce lower esophageal sphincter pressure[6-8].

Patients with cirrhosis are also reported to be at increased risk for esophageal cancer. In a case control study from Italy of 405 patients with esophageal cancers, cirrhotic patients were 2.6 times more likely to have esophageal cancer (95%CI: 1.2-5.7) than non-cirrhotic patients after adjusting for alcohol use, nicotine use and a history of hepatitis[9]. Also, in a nationwide cohort study from Denmark of 11605 patients with cirrhosis, there was a 7.5 fold increased risk of esophageal cancer compared to the general population (95%CI: 5.6-9.8)[10].

Despite the increased prevalence of GERD and esophageal cancer in cirrhotic patients, little is known about the occurrence of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) and its precursor lesion, Barrett’s esophagus (BE) in cirrhotic patients. One of the factors may be that even though cirrhotic patients undergo endoscopies for surveillance of varices, BE may be under recognized due to reluctance of endoscopists to biopsy esophageal mucosa in the presence of coexisting varices or bleeding diathesis in cirrhotic patients. However, instances of high grade dysplasia (HGD) or EAC have been reported in cirrhotic patients[11,12]. Therefore, our aim was to study the disease characteristics of BE in cirrhotic patients and to assess if they were at increased risk of progression to HGD/EAC when compared to BE patients without cirrhosis.

After obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board, all patients over the age of 18 years diagnosed with BE and cirrhosis in the department of Gastroenterology at our institution from January 1st 2000 to December 31st 2015 and enrolled in our Barrett’s registry were identified. Diagnostic criteria for cirrhosis included characteristic histological picture on liver biopsy or typical imaging findings on ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging or computerized tomography.

Patients were included in the study if they had undergone at least one upper endoscopy at our institution showing endoscopic evidence of BE and confirmed by the presence of intestinal metaplasia on histology. For surveillance, four quadrant biopsies were taken every 2 cm intervals from BE segments or every 1 cm in patients with known or suspected dysplasia as recommended in the Seattle protocol[13]. Dysplasia is graded per Vienna classification into no dysplasia, low grade dysplasia (LGD), high grade dysplasia (HGD) and cancer[14]. The histological category of indefinite for dysplasia was included under LGD as clinical management is similar. All cases of suspected dysplasia were evaluated by a gastrointestinal pathologist and confirmed by a second gastrointestinal pathologist or at pathology consensus conference. Upper endoscopies are performed by over fifty endoscopists from different specialties.

Information including patient demographics, body mass index (BMI), endoscopic findings (including length of BE, presence and size of hiatal hernia, presence of varices), histological findings (grade of dysplasia), Model for End-stage Liver Disease -Sodium (MELD-Na) score and Child- Pugh (CP) class were abstracted by review of patients’ charts. CP class and MELD-Na score were calculated from data available ± 12 mo from the date of the baseline endoscopy.

The primary end point was development of HGD/cancer in cirrhotic patients with BE and compare to controls. On retrospective review, we found 57 patients with BE and cirrhosis in our institution. Sample size calculation did not apply for this situation. To compare the rate of neoplastic progression, a control group was identified. The cirrhotic patients were matched 1: 4 to BE patients with no documented evidence of cirrhosis and adjusted for age at BE diagnosis (± 5 years), gender and BMI (± 1) using a Greedy algorithm.

Data are presented as mean ± SD, median [25th, 75th percentiles] or frequency (percent). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for continuous and ordinal factors and Fisher’s Exact tests were used for categorical variables. Cox regression analysis was used to assess progression and a hazards marginal model and robust sandwich estimators were used in order to account for matching. Incidence rates were estimated for each subgroup by dividing the total number of events by the total number of person-years. Poisson regression was used to assess differences between cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients and the log of follow-up years was used as the offset. Progression of disease was assessed in a subgroup of patients that had no HGD or cancer at baseline. Patients were divided into 2 subgroups: (1) no dysplasia; and (2) LGD at baseline, and progression was evaluated in these groups separately. A time-to-event analysis was performed to assess progression rates. Follow-up time was defined as months from the baseline endoscopy to the first endoscopy showing progression or last endoscopy if no progression was seen and was truncated at 5 years. Incidence rates were estimated for each subgroup by dividing the total number of events by the total number of person-years. Poisson regression was used to assess differences between cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic subjects; the log of follow-up years was used as the offset.

In addition, we assessed factors associated with progression in cirrhotic subjects without dysplasia at baseline using univariable Cox regression analysis. For this subgroup we assessed progression to LGD, HGD or cancer. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, The SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 57 patients with cirrhosis and BE were identified at our center. The mean age at the time of diagnosis of cirrhosis was 58.2 ± 11 years. The majority of patients were male (78.9%), Caucasian (98.2%) and overweight (BMI 30.6 ± 7.1). The patients had diverse etiologies of cirrhosis with the most common being non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in 21 (37.5%), cardiac cirrhosis in 12 (21.4%), and alcoholic liver disease in 8 (14.3%) patients in this cohort. A smaller proportion of patients had other etiologies of cirrhosis such as hepatitis C in 6 (10.7%), primary biliary cirrhosis in 5 (8.9%), autoimmune hepatitis in 3 (5.4%), hemochromatosis in 1 (1.8%), and hereditary causes in 1 (1.8%). A large proportion of patients were found to have co-morbidities including hypertension in 27 (47.4%), diabetes mellitus in 18 (31.6%), and hyperlipidemia in 20 (35.1%). On the index endoscopy, 16 (28.1 %) patients had esophageal varices. There were no bleeding complications noted during or after the procedure. In patients with varices, mucosa between the varices is biopsied. The CP class was A in 50 patients, B in 5 patients and C in one patient. MELD-Na score was 11 (± 5.1) in this cohort.

As shown in Table 1, at baseline endoscopy, 79% of the cirrhotic patients had nondysplastic BE (NDBE), 8.8% were found to have LGD, and 12.3% were found to have HGD or EAC. Notably, there was a significant association found between the presence of a hiatal hernia and the finding of dysplasia on endoscopy. Hiatal hernia was present in 80% of the LGD group, 28.6% of the HGD group and only 6.8% of the NDBE group (P < 0.001). Additionally, patients with HGD/EAC were more likely to be older at the age of BE diagnosis though this was not statistically significant. There was no significant association found between the presence of comorbidities, or endoscopic findings and the presence of dysplasia.

| No dysplasia (n = 45) | LGD (n = 5) | HGD/cancer (n = 7) | P value | |

| Male | 35 (77.8) | 3 (60.0) | 7 (100.0) | 0.24 |

| Age at cirrhosis diagnosis (yr) | 57.0 (50, 64) | 61 (48, 61) | 68 (58, 72) | 0.067 |

| Age at BE diagnosis (yr) | 57 (52, 64) | 57 (50, 62) | 67 (61, 71) | 0.055 |

| NASH | 17 (38.6) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (28.6) | 0.69 |

| Cardiac cirrhosis | 9 (20.5) | 2 (40.0) | 1 (14.3) | 0.52 |

| Hypertension | 23 (51.1) | 2 (40.0) | 2 (28.6) | 0.63 |

| Diabetes | 14 (31.1) | 2 (40.0) | 2 (28.6) | 0.88 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 16 (35.6) | 2 (40.0) | 2 (28.6) | 0.99 |

| Varices | 13 (28.9) | 2 (40.0) | 1 (14.3) | 0.66 |

| BE Length (cm) | 3.3 ± 3.3 | 5.0 ± 3.7 | 3.2 ± 4.6 | 0.58 |

| Presence of hiatal hernia | 3 (6.8) | 4 (80.0) | 2 (28.6) | < 0.0011 |

| Hiatal hernia length | 2.7 ± 0.58 | 4.3 ± 0.96 | 3.5 ± 0.71 | 0.11 |

| MELD-Na | 10.7 ± 4.5 | 13.5 ± 10.7 | 10.8 ± 2.7 | 0.59 |

| Child-Pugh class A | 39 | 5 | 6 | 0.68 |

| Class B | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Class C | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Follow-up (mo) | 34.9 (13.0, 63.7) | 44.2 (6.4, 50.6) | 13.8 (4.5, 41.0) | 0.16 |

A group of 228 patients with BE and no evidence of cirrhosis were matched to the 57 patients in the cirrhosis group. As shown in Table 2, the control group was well matched by age, gender, BMI, and ethnicity. On initial biopsy, both groups had comparable prevalence rates of LGD, HGD, and EAC. There was a higher prevalence of hiatal hernia in control group compared to the study group (56.1% vs 16.1%, P < 0.001). However, there was no significant difference between the two groups when comparing hiatal hernia length or BE length.

| No Cirrhosis(n = 228) | Cirrhosis(n = 57) | P value | |

| Male | 180 (78.9) | 45 (78.9) | 0.99 |

| Age at BE (yr) | 59.1 ± 9.6 | 58.9 ± 9.6 | 0.51 |

| Body mass Index (kg/m2) | 30.3 ± 6.0 | 30.6 ± 7.1 | 0.10 |

| Ethnicity | 0.97 | ||

| Caucasian | 214 | 54 | |

| African-American | 3 | 1 | |

| Other | 7 | 0 | |

| BE Length (cm) | 2.7 ± 3.1 | 3.5 ± 3.4 | 0.20 |

| Presence of hiatal hernia | 128 (56.1) | 9 (16.1) | < 0.0011 |

| Hiatal hernia length (cm) | 3.2 ± 1.5 | 3.6 ± 1.01 | 0.31 |

| Baseline biopsy | 0.10 | ||

| No dysplasia | 155 (68.0) | 45 (78.9) | |

| Low grade Dysplasia | 28 (12.3) | 5 (8.8) | |

| High grade Dysplasia | 29 (12.7) | 5 (8.8) | |

| Esophageal adenocarcinoma | 16 (7.0) | 2 (3.5) | |

| Number of endoscopies | 3 (2, 6) | 2 (2, 4) | 0.0091 |

| Follow-up endoscopy (mo) | 36.3 (13.6, 77.3) | 31.9 (12.5, 57.3) | 0.15 |

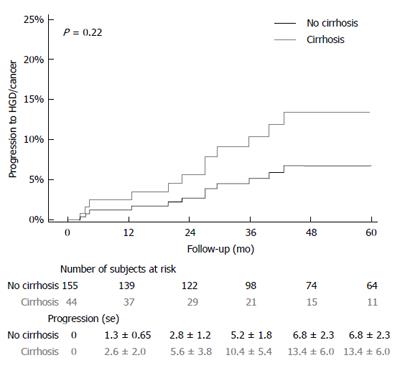

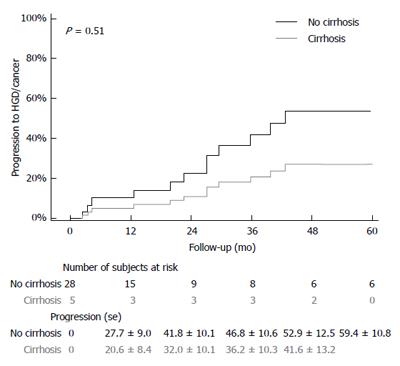

The median follow up time for entire study population was [3.0 (1.1, 6.0)] years with comparable duration for cases [2.7 (1.0, 4.8) years] and controls [3.0 (1.1, 6.4) years]. Among the 44 cirrhotic patients with follow up, 7 patients progressed to LGD, 2 patients progressed to HGD (one in NDBE group and one in LGD group) and 2 patients progressed to EAC (one each in NDBE group and LGD group). In the control group of 155 patients, 24 patients developed LGD, 14 patients developed HGD (seven in NDBE and five in LGD group) and 6 patients developed EAC (4 in NDBE and 2 in LGD groups). A time-to-event analysis was performed to assess progression rates in two subgroups of patients who either had NDBE or LGD on baseline endoscopy (Figures 1 and 2). Cirrhotic patients were found to have higher progression rates to both LGD and HGD/EAC, but this did not reach statistical significance.

Incidence rates were determined based on data from the 44 patients in the cirrhotic group with available follow-up endoscopies and 155 patients in the non-cirrhotic group (Table 3). In the study group, the rates of progression of NDBE to HGD/EAC was 1.1 per 100 person years compared to 1.4 per 100 person years in the control group (P = 0.8). The rates of progression of LGD to HGD/EAC were 13.7 and 8.1 per 100 person-years in the study and control groups respectively.

| Non-cirrhotic controls | Cirrhotic cases | P value | |

| (95%CI) | (95%CI) | ||

| No dysplasia at baseline | |||

| Person-years | 866.4 | 176.1 | - |

| LGD incidence per 100-person year | 2.8 (1.9, 4.1) | 4.0 (1.9, 8.4) | 0.40 |

| HGD incidence per 100-person year | 0.92 (0.46, 1.8) | 0.57 (0.08, 4.0) | 0.65 |

| EAC incidence per 100-person year | 0.46 (0.17, 1.2) | 0.57 (0.08, 4.0) | 0.85 |

| HGD/EAC incidence per 100-person year | 1.4 (0.79, 2.4) | 1.1 (0.28, 4.6) | 0.80 |

| LGD at baseline | |||

| Person-years | 86.9 | 14.6 | - |

| HGD incidence per 100-person year | 5.8 (2.4, 13.8) | 6.9 (0.97, 48.8) | 0.87 |

| EAC incidence per 100-person year | 2.3 (0.58, 9.2) | 6.9 (0.97, 48.8) | 0.37 |

| HGD/Cancer incidence per 100-person year | 8.1 (3.8, 16.9) | 13.7 (3.4, 55.0) | 0.51 |

A univariable analysis was done to assess factors associated with progression from no dysplasia at baseline to any type of dysplasia in cirrhotic patients (Table 4). For every one point increase in baseline CP class, risk of neoplastic progression increased by a factor of 8 (95%CI: 2.0-30.9, P = 0.003). There was no association found between gender, age, co-morbidities, MELD-Na scores, BE length, hiatal hernia size and progression of BE. A multivariable analysis was not done due to very few cases of progression.

| Factor | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| Male | 1.9 (0.31, 11.6) | 0.49 |

| Age at Cirrhosis diagnosis (yr) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.09) | 0.31 |

| Age at BE diagnosis (yr) | 1.04 (0.97, 1.1) | 0.28 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 0.89 (0.79, 1.02) | 0.085 |

| Child-Pugh Class | 7.9 (2.0, 30.9) | 0.0031 |

| Hypertension | 0.72 (0.21, 2.5) | 0.61 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 0.86 (0.22, 3.3) | 0.83 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.60 (0.16, 2.3) | 0.46 |

| MELD-Na | 1.08 (0.95, 1.2) | 0.23 |

| BE length (cm) | 1.1 (0.89, 1.4) | 0.32 |

| Hiatal Hernia size (cm) | 1.7 (0.28, 10.5) | 0.56 |

Approximately 60% of the BE and cirrhosis cohort had cirrhosis secondary to NASH and or cardiac cirrhosis. When compared to BE patients without cirrhosis, BE patients with cirrhosis are at higher risk of neoplastic progression but this did not reach statistical significance. We also found that higher CP score was associated with increased risk of neoplastic progression.

We noted a high prevalence of NASH and cardiac cirrhosis in our BE patients with cirrhosis. This is in sharp contrast to the widely prevalent etiologies of cirrhosis in the United States such as hepatitis C and alcoholic liver disease which account for 62% of cases. Of note, in general US population, NASH accounts for only 18% of cases[15]. This disproportionate representation of NASH in this study cohort may be due to shared risk factors between NASH cirrhosis and BE.

There are multiple studies on the role of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes mellitus (DM) in the development of NASH[16]. These factors have also been implicated in pathogenesis of BE and EAC. One meta-analysis found a significant association visceral obesity and the development of BE independent of GERD[17]. Another case-control study demonstrated that metabolic syndrome was associated with a two fold increase in risk for development of BE, independent of smoking, alcohol use and BMI[18]. Additionally, in a population-based case-control study, DM was associated with a 49% increase in the risk of BE[19]. The common denominator underlying metabolic syndrome, NASH and BE may be adipokines and other inflammatory cytokines. Visceral adipose tissue is metabolically active and produces hormones called as adipokines and inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α which interfere with glucose-insulin regulation and are linked to the development of metabolic syndrome[20]. Decreased serum adiponectin and elevated levels of circulating visfatin, IL-8, and TNF-α have been associated with NASH[21]. Similarly, BE is associated with an increase in the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-12p70, IL-6 and IL-8 and leptin and decrease in adiponectin compared to controls[22]. A large meta-analysis has also directly linked adipokines with the development of esophageal metaplasia, dysplasia, and neoplasia[23]. Although alcohol accounts for over 60% cases of cirrhosis in United States population, it was the main etiological factor in only 14.3% of cases of BE with cirrhosis in our study. Whether this is due to the protective effects of alcohol on BE is uncertain as some studies show lack of effect[24,25] and others show a slight protective effect[26].

In our study population, there was a trend towards increased rates of neoplastic progression in BE among cirrhotic patients compared to matched non-cirrhotic patients. This is important, as multiple population based studies have demonstrated a rising incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in the US population[27,28]. Therefore, cirrhotic patients, who are a population that is often under-biopsied because of fears of complications, may not be getting adequate surveillance for BE[29]. In addition, bleeding diathesis and portal hypertension in cirrhotic patients may increase the risk of bleeding complications during endoscopic eradication therapies for BE associated dysplasia. Correction of these factors is essential before any therapeutic interventions are contemplated. Further prospective studies would be required to better address this.

Our study demonstrated a statistically significant relationship between an increased CP class, and the risk of progression to dysplasia. The CP class is used as a proxy for determining liver disease severity and is useful for predicting mortality[30]. Elevated scores are associated with more advanced liver disease. This association is likely due to the increased levels of certain humoral factors in advanced liver disease. Studies have demonstrated that there are elevated levels of vasoactive intestinal peptide, neurotensin and nitrous oxide in cirrhotics with worsening liver function. These factors are known to lower LES pressure thereby facilitating GERD, the strongest risk factor for the development of BE[8-10]. However, we did not find any association between the MELD-Na score, another popular tool for analyzing liver disease severity, and progression of BE. This may be due to the lack of necessary data in a significant proportion of patients (22 out of 57 patients) for MELD-Na calculation.

To our knowledge there are no other studies to date that studied a large population of patients with both BE and cirrhosis. One of the major strengths of our study is the use of stringent criteria for defining BE, i.e., intestinal metaplasia in distal esophagus of any length and use of expert confirmation of all cases of dysplasia in BE. Also, to study if cirrhosis itself is a risk factor for progression, we used a well matched control group of BE without cirrhosis. Our population also consists of mostly older, Caucasian men which correlates with the most at-risk population for BE.

As this is a retrospective case-control study, it has several limitations. Even though liver dysfunction was associated with development of dysplasia, we did not find any statistically significant difference in the incidence rates of dysplasia which may be due to type II error. A larger study on a more diverse group of BE patients may yield more definitive results. As this a retrospective study, follow-up data is not available in all the patients which limits our ability to ascertain true progression rates. Also data regarding other factors such as smoking and use of medications such as aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, proton pump inhibitors which may affect progression rates was not available. Pertinent data were sometimes missing from the electronic medical record increasing the possibility of confounding factors introducing bias.

In conclusion, particular attention should be paid to screening for BE in patients with NASH and cardiac cirrhosis as there seems to be an association between both these conditions. Patients with worsening liver function have higher risk of progression of BE and may need frequent surveillance. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm this association and to identify underlying pathophysiology.

The prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in patients with liver cirrhosis is high with estimates ranging from approximately 37% to 64%. Patients with cirrhosis are also reported to be at increased risk for esophageal cancer.

Despite the increased prevalence of GERD and esophageal cancer in cirrhotic patients, little is known about the occurrence of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) and its precursor lesion, Barrett’s esophagus (BE) in cirrhotic patients.

Fifty seven cirrhotic patients with Barrett’s esophagus were compared to 228 non-cirrhotic BE controls. NASH (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis) or cardiac cirrhosis were the most common causes of cirrhosis in this group. There were no differences in incidence rates of HGD/EAC in nondysplastic BE between cirrhotic cases and noncirrhotic controls (1.4 vs 1.1 per 100 person -years, P = 0.8) In LGD, cirrhotic patients were found to have higher rates of progression to HGD/EAC compared to control group though this did not reach statistical significance (13.7 vs 8.1 per 100 person- years, P = 0.51). There was approximately 8 times increased risk of progression for every one point increase in Child- Pugh class.

Particular attention should be paid to screening for BE in patients with NASH and cardiac cirrhosis as there seems to be an association between both these conditions. BE patients with worsening liver function have higher risk of progression of BE and may need frequent surveillance.

It is studying the characteristics of BE in cirrhotic patients and a possible link between cirrhosis and Barrett’s esophagus’ malignant progression. The article is well written and its structure is good.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Greenspan M, Kaname U, Nathanson BH, Nagahara H, Phillip Beales IL, Sanaei O S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Locke GR, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448-1456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1488] [Cited by in RCA: 1379] [Article Influence: 49.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schechter RB, Lemme EM, Coelho HS. Gastroesophageal reflux in cirrhotic patients with esophageal varices without endoscopic treatment. Arq Gastroenterol. 2007;44:145-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ahmed AM, al Karawi MA, Shariq S, Mohamed AE. Frequency of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1993;40:478-480. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Passaretti S, Mazzotti G, de Franchis R, Cipolla M, Testoni PA, Tittobello A. Esophageal motility in cirrhotics with and without esophageal varices. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24:334-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bhatia SJ, Narawane NM, Shalia KK, Mistry FP, Sheth MD, Abraham P, Dherai AJ. Effect of tense ascites on esophageal body motility and lower esophageal sphincter pressure. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1999;18:63-65. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Richter JE. Role of the gastric refluxate in gastroesophageal reflux disease: acid, weak acid and bile. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338:89-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Okamoto E, Amano Y, Fukuhara H, Furuta K, Miyake T, Sato S, Ishihara S, Kinoshita Y. Does gastroesophageal reflux have an influence on bleeding from esophageal varices? J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:803-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Papadopoulos N, Soultati A, Goritsas C, Lazaropoulou C, Achimastos A, Adamopoulos A, Dourakis SP. Nitric oxide, ammonia, and CRP levels in cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy: is there a connection? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:713-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kalaitzakis E, Gunnarsdottir SA, Josefsson A, Björnsson E. Increased risk for malignant neoplasms among patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:168-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sorensen HT, Friis S, Olsen JH, Thulstrup AM, Mellemkjaer L, Linet M, Trichopoulos D, Vilstrup H, Olsen J. Risk of liver and other types of cancer in patients with cirrhosis: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Hepatology. 1998;28:921-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Raftopoulos SC, Efthymiou M, May G, Marcon N. Dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus in cirrhosis: a treatment dilemma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1724-1726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Palmer WC, Di Leo M, Jovani M, Heckman MG, Diehl NN, Iyer PG, Wolfsen HC, Wallace MB. Management of high grade dysplasia in Barrett’s oesophagus with underlying oesophageal varices: A retrospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:763-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Reid BJ, Weinstein WM, Lewin KJ, Haggitt RC, VanDeventer G, DenBesten L, Rubin CE. Endoscopic biopsy can detect high-grade dysplasia or early adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus without grossly recognizable neoplastic lesions. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:81-90. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, Borchard F, Cooper HS, Dawsey SM, Dixon MF, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Fléjou JF, Geboes K. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut. 2000;47:251-255. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Schuppan D, Afdhal NH. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2008;371:838-851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1686] [Cited by in RCA: 1554] [Article Influence: 91.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, Forlani G, Cerrelli F, Lenzi M, Manini R, Natale S, Vanni E, Villanova N, Melchionda N. Nonalcoholic fatty liver, steatohepatitis, and the metabolic syndrome. Hepatology. 2003;37:917-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1907] [Cited by in RCA: 1910] [Article Influence: 86.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cook MB, Greenwood DC, Hardie LJ, Wild CP, Forman D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the risk of increasing adiposity on Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:292-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Thrift AP, Hilal J, El-Serag HB. Metabolic syndrome and the risk of Barrett’s oesophagus in white males. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:1182-1189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Leggett CL, Nelsen EM, Tian J, Schleck CB, Zinsmeister AR, Dunagan KT, Locke GR, Wang KK, Talley NJ, Iyer PG. Metabolic syndrome as a risk factor for Barrett esophagus: a population-based case-control study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:157-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Iyer PG, Borah BJ, Heien HC, Das A, Cooper GS, Chak A. Association of Barrett’s esophagus with type II Diabetes Mellitus: results from a large population-based case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1108-1114.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jamali R, Arj A, Razavizade M, Aarabi MH. Prediction of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Via a Novel Panel of Serum Adipokines. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Garcia JM, Splenser AE, Kramer J, Alsarraj A, Fitzgerald S, Ramsey D, El-Serag HB. Circulating inflammatory cytokines and adipokines are associated with increased risk of Barrett’s esophagus: a case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:229-238.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chandar AK, Devanna S, Lu C, Singh S, Greer K, Chak A, Iyer PG. Association of Serum Levels of Adipokines and Insulin With Risk of Barrett’s Esophagus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:2241-55.e1-4; quiz e179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Navab F, Nathanson BH, Desilets DJ. The impact of lifestyle on Barrett’s Esophagus: A precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39:885-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Anderson LA, Cantwell MM, Watson RG, Johnston BT, Murphy SJ, Ferguson HR, McGuigan J, Comber H, Reynolds JV, Murray LJ. The association between alcohol and reflux esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:799-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Xu Q, Guo W, Shi X, Zhang W, Zhang T, Wu C, Lu J, Wang R, Zhao Y, Ma X. Association Between Alcohol Consumption and the Risk of Barrett’s Esophagus: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Blot WJ, Devesa SS, Kneller RW, Fraumeni JF. Rising incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. JAMA. 1991;265:1287-1289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1287] [Cited by in RCA: 1149] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Brown LM, Devesa SS. Epidemiologic trends in esophageal and gastric cancer in the United States. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2002;11:235-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ross WA. Endoscopic Interventions in Patients with Thrombocytopenia. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2015;11:115-117. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Peng Y, Qi X, Guo X. Child-Pugh Versus MELD Score for the Assessment of Prognosis in Liver Cirrhosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 333] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |