Published online May 7, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i17.3174

Peer-review started: October 7, 2016

First decision: November 9, 2016

Revised: December 2, 2016

Accepted: January 11, 2017

Article in press: January 11, 2017

Published online: May 7, 2017

Processing time: 213 Days and 14.9 Hours

To determine the impact of upwards titration of proton pump inhibition (PPI) on acid reflux, symptom scores and histology, compared to clinically successful fundoplication.

Two cohorts of long-segment Barrett’s esophagus (BE) patients were studied. In group 1 (n = 24), increasing doses of PPI were administered in 8-wk intervals until acid reflux normalization. At each assessment, ambulatory 24 h pH recording, endoscopy with biopsies and symptom scoring (by a gastroesophageal reflux disease health related quality of life questionnaire, GERD/HRLQ) were performed. Group 2 (n = 30) consisted of patients with a previous fundoplication.

In group 1, acid reflux normalized in 23 of 24 patients, resulting in improved GERD/HRQL scores (P = 0.001), which were most pronounced after the starting dose of PPI (P < 0.001). PPI treatment reached the same level of GERD/HRQL scores as after a clinically successful fundoplication (P = 0.5). Normalization of acid reflux in both groups was associated with reduction in papillary length, basal cell layer thickness, intercellular space dilatation, and acute and chronic inflammation of squamous epithelium.

This study shows that acid reflux and symptom scores co-vary throughout PPI increments in long-segment BE patients, especially after the first dose of PPI, reaching the same level as after a successful fundoplication. Minor changes were found among GERD markers at the morphological level.

Core tip: This study evaluated the effects of increasing, acid-reflux-adjusted doses of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) on symptoms and histology in Barrett’s esophagus (BE) patients in comparison to BE patients with a clinically successful fundoplication. All patients went through an extensive prospective protocol with symptom assessment, upper endoscopy with biopsies, 24 h pH-monitoring and manometry. In the non-operated group, 42% of patients needed more than the standard PPI dose to reach acid control which then was associated with improvement of symptom scores up to the same levels as after successful fundoplication. In addition, acid reflux control was associated with changes in the esophageal columnar and squamous epithelium, regardless of medical or surgical treatment.

- Citation: Baldaque-Silva F, Vieth M, Debel M, Håkanson B, Thorell A, Lunet N, Song H, Mascarenhas-Saraiva M, Pereira G, Lundell L, Marschall HU. Impact of gastroesophageal reflux control through tailored proton pump inhibition therapy or fundoplication in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(17): 3174-3183

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i17/3174.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i17.3174

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is a pre-malignant condition characterized by the presence of metaplastic columnar lined epithelium in the distal esophagus and is considered a complication of longstanding chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)[1]. Several studies have highlighted the role of acidic and non-acidic components of the refluxate in the genesis of symptoms and in the initiation and progression of BE[2,3].

In clinical practice, the management of GERD patients with and without BE is based on a pragmatic approach where the dose of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) is adjusted to achieve relief of symptoms[4]. At a group level, this strategy seems to be operational, although there may be significant dissociations between symptom control and the degree of acid suppression[5]. The long-term consequences of symptom-based reflux control on BE progression are not known[6] and there is no clear consensus on the efficacy of standard and modified doses of PPI in BE. Some studies show an effect of increased doses on acid reflux variables[7,8] while others do not[9].

Of note, adequate acid suppression also reduces the refluxate volume which, in addition, affects the non-acidic reflux[10], but anti-reflux surgical repair in BE patients might be advantageous as it may provide total control of any duodeno-gastro-esophageal reflux. A reasonable assumption with clinical relevance is that all long-term therapies in BE patients should aim to eliminate abnormal acid exposure to the susceptible columnar mucosa. In fact, a reduction in the rate of cell proliferation may occur as a consequence of normalization of esophageal pH[11].

The objectives of the present study were primarily to determine whether the acid reflux variables co-varied with the symptom scores throughout the upwards titration of PPI dosing in long-segment BE patients and whether it was possible to eliminate acid reflux in these patients. An additional question raised was if medical therapy could achieve the same level of acid reflux and symptom control as a clinically successful total fundoplication. In parallel with these clinical parameters, we studied the morphological changes in the columnar, as well as the squamous epithelium, to evaluate whether these alterations co-varied with the acid reflux variables in respective groups.

Fifty-eight adult patients with long-segment BE (> 3 cm) without (group 1, n = 27) or with anti-reflux surgery (fundoplication > 5 years prior to inclusion; group 2, n = 31) participated in this prospective study. Inclusion criteria were: presence of columnar lined esophagus with specialized intestinal metaplasia in biopsies taken according to the Seattle protocol[12], and in group 2 denial of any GERD-related symptom and any use of H2 blockers or PPI recorded in a screening telephone interview. All patients in group 1 had a history of PPI treatment for > 6 mo.

Exclusion criteria were: the presence of esophageal strictures, neoplasia, previous endoscopic treatment in the esophagus, upper gastrointestinal surgery other than anti-reflux surgery, pregnancy, liver disease, coagulation or mental disorders, use of anticoagulants or NSAID.

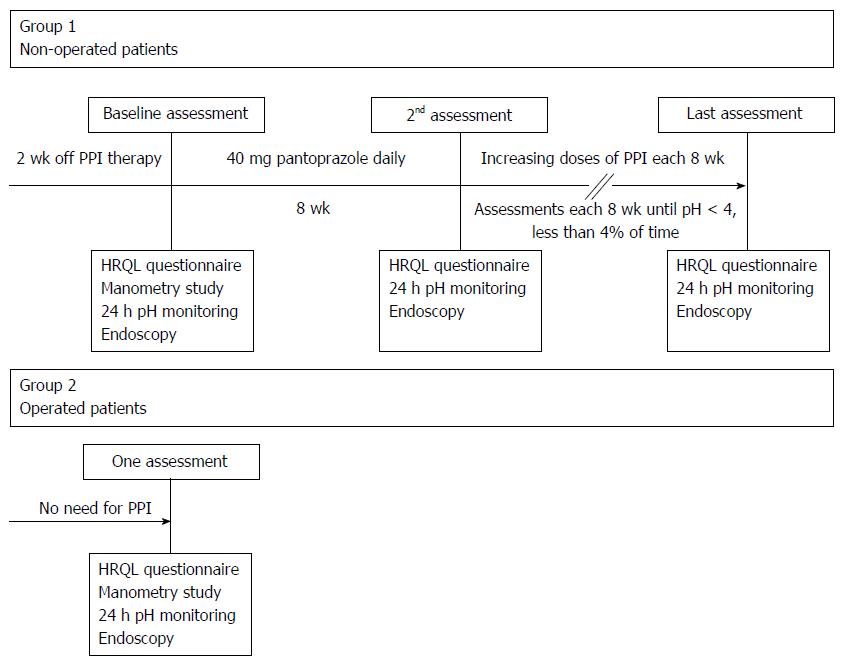

Patients in group 1 underwent at each visit upper endoscopy, ambulatory 24 h pH recording and symptom assessment (Figure 1). At the first visit, esophageal manometry was also performed to facilitate the correct positioning of the pH electrode. Otherwise we have chosen not to present any esophageal motility data. Drugs that might influence gastrointestinal motility and H2 blockers or PPI had to be discontinued for at least two weeks before the first assessment.

After the first visit, group 1 patients started PPI (pantoprazole) with a daily morning (before breakfast) dose of 40 mg for 8 wk, followed by re-evaluation with ambulatory 24 h pH recording, endoscopy and symptom assessment. In patients with persisting pathologic pH values, the dose of pantoprazole was increased to 80 mg/d (b.i.d.) for another 8 wk, and, in those still not reaching the study end point of normalized acidic reflux, to 120 mg/d (b.i.d. or t.i.d. according to pH-metry results) for an additional 8 wk (Figure 1). Beyond this maximum dose, an additional oral H2 receptor antagonist (ranitidine 300 mg) for control of night-time heartburn was allowed. In cases of intolerance or incomplete response to pantoprazole, patients were switched to the same dose of esomeprazole. In group 2 patients, only the baseline investigations were performed.

At each endoscopy, a standardized protocol was used as described before[13]. Biopsies were taken at the 3 o’clock position: in the anatomical cardia, at each 2 cm from distal to proximal BE, at the BE-neosquamous junction, and finally, 1 cm proximal of it.

At each visit, patients completed a validated disease-specific quality of life questionnaire (GERD-HRQL), where higher scores represented more severe symptoms and impaired quality of life. This questionnaire uses 10 questions graded on a 0-5 scale with a maximum score of 50, evaluating 4 main domains: intensity and frequency of heartburn, difficulty of swallowing, bloating, and burden of GERD medication[14].

Stationary esophageal manometry was performed at the first visit to locate the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Patients were counselled to maintain their usual daily activities and eating and sleeping habits during the 24 h pH recording. Symptoms, meals and postural changes were recorded by the patients, using event markers on the data waist recorder. Intraluminal 24 h pH monitoring was performed using dedicated pH electrodes (Versaflex, Alpine Biomed, Fountain Valley, CA, United States). The pH electrode was positioned 5 cm above the upper margin of the LES. In each pH tracing, the percentage of total time with an esophageal pH < 4, percentage in the supine and erect position, the total numbers of reflux episodes and the longest episode and the reflux index were analyzed. A pH < 4 during less than 4% of time was considered as normalized acid reflux[15].

Biopsy specimens were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and reviewed by 2 expert gastrointestinal pathologists (Debel M and Vieth M) who were blinded to the patients’ group affiliation and clinical findings.

The histological assessment of the squamous epithelium included scoring of basal cell layer and epithelial total thicknesses, papillary length, intercellular space dilation and number of inflammatory cells (neutrophils, eosinophils and mononuclear cells) accordingly to published guidelines[16]. Columnar epithelium was evaluated for the presence of specialized intestinal metaplasia, inflammatory cells and intraepithelial neoplasia, which was defined according to the World Health Organization classification[17]. Specific antibodies to CD10 (56C6 Novocastra, Newcastle, United Kingdom) and Ki67 (clone K-2, Zytomed Systems, Berlin, Germany) were used as markers for differentiation and proliferation, respectively. For retrieval of antigens, deparaffinised sections were heated in citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by 20 min incubation with 0.3% hydrogen peroxidase in absolute methanol. Sections were washed and non-specific binding was blocked by the use of normal serum (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan). Overnight incubation at 4 °C was carried out for binding of the primary antibody. Afterwards, 30 min incubation with biotinylated secondary antibody was performed followed by substrate binding by using streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase method. Additional counterstaining with haemalaun was carried out in all cases. All stains were accompanied by negative and positive controls and only accepted if controls showed expected results. Otherwise, staining was repeated until internal controls showed appropriate results[18]. For evaluation of the proliferation index, cells in the most affected area with positive signals against Ki67 were counted and scored along a 0-3 scale, where grade 0 ≤ 5%; grade 1 = 5%-35%; grade 2 = 36%-65%; grade 3 ≥ 65% of the cells stained positive[11]. CD10 was semiquantitatively graded according to the Remmele Score system[18].

Statistical software STATA (Version 11.2, Stata Corp, College Station, TX, United States) was used for data analyses. Values were expressed as median and interquartile ranges (IQR). Differences between groups 1 and 2, in HRQL and in acid reflux, were evaluated using the Wilcoxon test; comparisons between subgroups (e.g., group 1 reflux vs group 2 reflux) were conducted using Mann-Whitney U test.

This study was performed according to the Helsinki declaration after obtaining written informed consent of all participants and was approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (Dnr 04534/2).

There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the patients in groups 1 and 2 (Table 1). Three patients in group 1 dropped out at the baseline assessment, two due to technical problems with pH monitoring and one due to a large hiatal hernia precluding manometry, which was also the reason for one drop-out in group 2. Thus, the final analyses were based on: 24 patients (18 males, 6 females) in group 1 with a median age of 64.7 years (range 43-77 years) and median BE length 5 cm (range 3-15 cm); and 30 patients (23 males, 7 females) in group 2 with a median age of 64.2 years (range 37-73 years) and median BE length 5 cm (range 3-12 cm).

| Patients characteristics | Group 1 (n = 24) | Group 2 (n = 30) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 64.7 (56.0-67.9) | 64.2 (60.0-67.6) | 0.889 |

| Gender, % men | 75 | 77 | 0.887 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.6 (25.0-30.3) | 26.2 (25.0-29.1) | 0.623 |

| Smoking, % current smokers | 20.8 | 10.7 | 0.313 |

| Barrett’s esophagus length (cm) | |||

| C (circular extension) | 2 (1-6) | 1 (0-3) | 0.099 |

| M (maximal extension) | 5 (4-8) | 5 (3-7) | 0.278 |

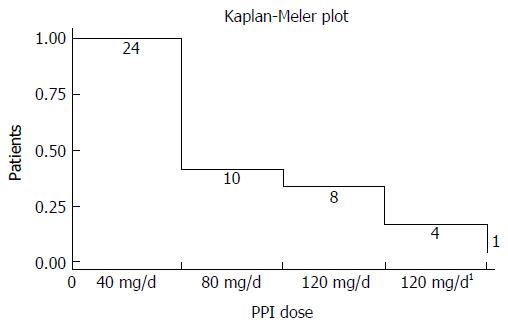

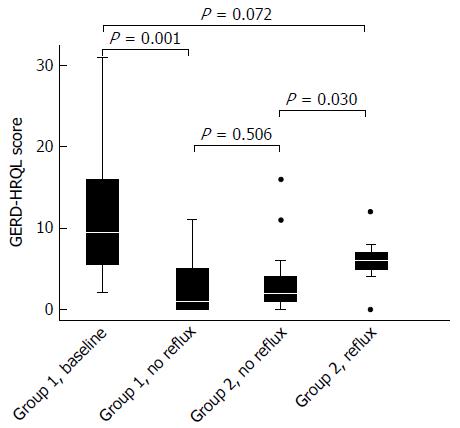

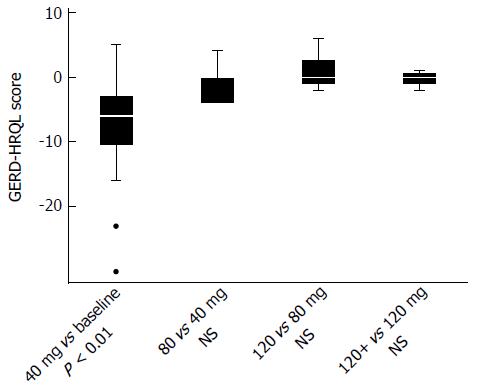

In group 1 at baseline, a significant correlation between total acidic reflux time and both circumferential and total BE length was observed (P = 0.002 and 0.003, respectively). A daily dose of 40 mg of pantoprazole normalized acid reflux in 14 of 24 (58%) patients in group 1. Doubling the dose to 80 mg/d normalized another 2 patients. In the 8 remaining patients with abnormal acid reflux, the dose was then escalated to 120 mg/d. Among those, 3 still remained unresponsive with abnormal acid reflux, while 1 patient did not tolerate the highest dose of pantoprazole. Three of these 4 patients finally normalized acid reflux after switching to esomeprazole 120 mg/d and bed-time ranitidine 300 mg, leaving only 1 patient with continued elevated esophageal acid exposure (Figure 2). For the entire group of BE patients, we observed that normalization of acid reflux was associated with a significant reduction in GERD/HRQL symptoms as compared to baseline values (P = 0.001; Figure 3). However, when considering each individual step of the respective dose escalation, we were able to statistically substantiate a clear difference in GERD/HRQL symptoms as a response only to the initial 8 wk of therapy (i.e., 40 mg daily of pantoprazole, P < 0.001; Figure 4). The ensuing escalation of PPI dosing was not followed by changes in symptom scorings which reached statistical significance. There were no differences in acid reflux variables related to supine or upright body positions (data not shown).

In group 2, abnormal acid reflux with a total reflux time of 18.9% (range 7.5%-27.3%) was detected in 12/30 (40%) patients; in the remaining 18 patients with a fundoplication, a total reflux time of 0.7% (range 0%-4%) was recorded. Absence of pathological acidic reflux in anti-reflux-operated patients was associated with significantly lower GERD-HRQL symptom scores (P = 0.030, Figure 3) attaining the same level as PPI-treated BE patients with normalization of acid reflux (Figure 3).

At baseline, established squamous epithelium markers for GERD, i.e., papillary length, basal cell layer thickness and width of intercellular spaces were all increased (Table 2), as compared to published data from healthy subjects[16]. Normalization of acid reflux decreased most of these variables, reaching statistical significance for intercellular spaces and papillary lengths in squamous epithelium of group 1 (Table 2). In patients of group 2, a similar picture emerged with values indicating improved basal cell thickness in those having non-pathological reflux. In the squamous, as well as in the columnar epithelium, the inflammation scores did not change in a consistent way, neither from the distal to the more proximally located biopsy sites, nor in response to therapy (Table 2).

| Variable | Group 1, baseline(n = 23) | Group 1, no reflux(n = 23) | P value | Group 2, reflux(n = 14) | Group 2, no reflux(n = 16) | P value |

| Squamous epithelium | ||||||

| Dilated intercellular space (%) | 87.0 | 73.9 | < 0.05 | 78.6 | 68.8 | 0.50 |

| Basal cell thickness (% score 0/1/2) | 4.3/82.7/13.0 | 21.7/69.6/8.7 | 0.22 | 50.0/50.0/0 | 12.5/87.5/0 | < 0.05 |

| Papillary length (% score 0/1/2) | 0/34.8/65.2 | 8.7/52.2/39.1 | < 0.05 | 7.1/42.9/50.0 | 18.8/43.7/37.5 | 0.53 |

| Epithelial neutrophils and eosinophils (% score 0/1/2) | 39.2/30.4/30.4 | 47.8/26.1/26.1 | 0.86 | 35.7/50.0/14.3 | 62.5/25/12.5 | 0.27 |

| Epithelial mononuclear cells (% score 0/1/2) | 60.9/39.1/0 | 87.0/13.0/0 | 0.09 | 57.1/42.9/0 | 56.3/43.7/0 | 0.47 |

| Proximal BE | ||||||

| Epithelial neutrophils and eosinophils (% score 0/1/2) | 43.5/30.4/26.1 | 47.8/30.4/21.7 | 0.06 | 42.9/21.4/35.7 | 81.3/6.2/12.5 | < 0.05 |

| Epithelial mononuclear cells (% score 0/1/2) | 91.3/8.7/0 | 95.7/4.3/0 | 0.26 | 92.9/7.1/0 | 93.7/6.3/0 | 0.24 |

| Distal BE | ||||||

| Epithelial neutrophils and eosinophils (% score 0/1/2) | 78.3/8.7/13.0 | 82.6/13/4.4 | 0.74 | 85.7/0/14.3 | 43.8/50/6.2 | < 0.05 |

| Epithelial mononuclear cells (% score 0/1/2) | 73.9/13.0/13.0 | 56.5/39.1/4.4 | 0.10 | 92.9/7.1/0 | 100/0/0 | 0.09 |

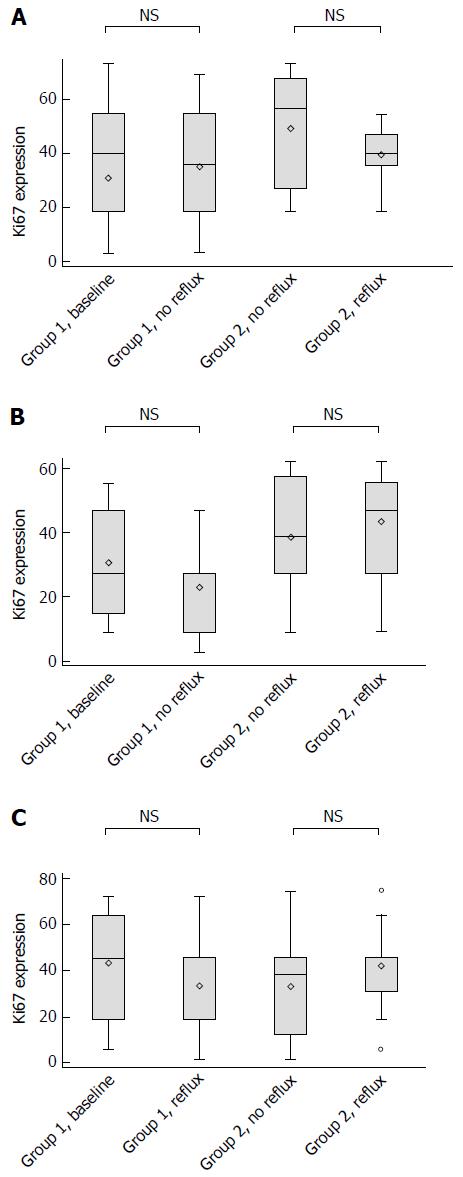

The CD10 marker of differentiation stained negative from baseline and onwards regardless of location of the tissue samples. Figure 5 shows the semiquantitative analyses of Ki67 in the columnar lined esophagus and in the squamous epithelium 1 cm above the neo-squamo-columnar junction. No effects were detected by normalization of acid reflux parameters, neither in the columnar lined esophagus (irrespective of location), nor in the squamous epithelium. Moreover, we were unable to detect any differences between patients on PPI and those with a previous fundoplication. In the latter group, we found no differences between those who, despite symptom control, had remaining abnormal acid reflux and those in whom reflux had been completely eliminated (Figure 5A-C).

The present study addressed whether intraesophageal acid reflux variables co-varied with symptom scores in patients with long-segment BE, throughout the upwards titration of PPI doses. We, like others, observed an association between the degree of symptom relief and the change in acid reflux[19]. Secondly, we tried to ascertain whether it was possible to completely normalize acid reflux in long-segment BE patients, based on the principle of step-wise increasing doses of the PPI, adjusted to the remaining reflux patterns detected during ambulatory 24-h pH monitoring. Our results showed that this is accomplishable, albeit at the cost of high daily doses and eventually a change to another PPI. A further question then arose, namely whether tailored medical therapy could reach the same level of reflux and symptom control as a clinically successful fundoplication. The answer seems to be that there is no difference in symptom profiles between these two patient groups.

Finally, we studied morphological changes in the columnar mucosa and in the squamous epithelium immediately adjacent to the neo-squamous-columnar junction, elucidating whether abnormal features prevailed and, if so, whether these alterations were concomitant with changes in acid reflux variables. Changes in acute and chronic inflammation markers did not display a consistent pattern with the control of acid reflux, and no differences were found between those given PPI and those who had underfone clinically successful anti-reflux surgery. However, an improvement was recorded in the squamous epithelium in most parameters considered to represent reflux-induced damage[16]. Of note, we described far more discrete changes in response to therapy than previously observed in the distal esophagus of GERD patients without BE[20]. Markers for the proliferative drive on the columnar lined, as well as squamous epithelium, were outside the normal ranges[16] but importantly, these parameters remained stable and unaffected either by uptitration of PPI doses or by the presence of a well-functioning anti-reflux valve. It can be argued that the patients who received a PPI in our study were not treated long enough to “normalize” the histological findings[16]. The relevance of this can be questioned based on the stable histological findings made in patients submitted to a fundoplication at least 5 years before the actual investigations.

Medical therapy of GERD that is solely based on acid inhibition has been debated, as it might neglect the pathogenetic importance of the extragastric (biliary) components of the refluxate[3]. In fact, some older comparative studies between anti-reflux surgery and medical acid inhibitory therapy have suggested an inferiority of the latter[21]. Our data are quite concordant with those from the recent LOTUS trial in chronic GERD patients that do not support this concept[22]. Current evidence therefore suggests that acid is the most important component of the refluxate in generating and controlling GERD symptoms.

A remaining controversy concerns how effective standard and modified doses of PPIs are in BE in general and in long-segment BE in particular. Some studies report a lack of additional effect of higher doses[7] while others claim the opposite[8,9]. This issue is important, since in clinical practice the management of GERD patients in general and BE patients in particular is based on a pragmatic concept, where the dose of PPI is solely adjusted to achieve symptom control[10]. At a group level this strategy seems to prevail, but a significant dissociation exists at an individual level between symptom control and the degree to which acid reflux is controlled[23]. In the present study the symptom relief-dose response curve seemed to be extremely steep with a predominant effect for the starting dose of pantoprazole. Step-wise increases of the PPI to 80-120 mg daily normalized the intraesophageal acid exposure in all but one of the remaining study subjects and was statistically significant over the entire study protocol.

Although our operated patients considered themselves as symptom-free at a telephone interview, a significant number of them still displayed abnormal acid reflux. Indeed, we found subtle symptom differences between acid refluxers and those in whom reflux had been totally normalized. These results highlight the fact that some operated patients with long-segment BE might have significant reflux despite being judged to be asymptomatic and that anti-reflux surgery in long-segment BE patients might not be as successful as in chronic GERD in general. This illustrates the importance of adding objective means to determine the efficacy and durability of GERD control after surgical repair, especially in BE.

Support for a PPI-based long-term therapeutic strategy in BE is given by epidemiological data showing that long-term, potent acid-inhibitory therapy seems to reduce the risk for the development of neoplastic lesions in the columnar metaplastic epithelium[24,25]. Indeed, recent data suggest a true preventive effect of acid inhibition medication on the risk of high grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma development in BE patients[26]. Since even short acid pulses can stress Barrett’s mucosa in an unfavorable direction, the present results would offer additional background data supporting the use of a tailored dose strategy in high-risk BE individuals[27]. The deleterious effects of the refluxate on the cell kinetics of squamous epithelium at the gastro-esophageal junction and in the distal esophagus have been studied in chronic GERD patients by exploring the expression of Ki67[28]. Overexpression of Ki67 has been confirmed in BE[29] and may represent a suitable biomarker of cellular proliferation progressing towards neoplasia. In this study, we evaluated Ki67 expression along the columnar lined epithelium and in the squamous epithelium closely proximal to the neo-squamo-columnar junction and found similar expression rates in patients treated with PPI and anti-reflux surgery. In parallel with the assessment of the proliferation index, we also tried to evaluate the strains on tissue differentiation towards intestinal character of the columnar mucosa by the use of CD10. However, in none of the tissue specimens were we able to detect any changes in the differentiation and proliferation markers. Therefore the current findings might reflect a characteristic phenotype of long-segment BE patients rather than a response to the damaging effect of the refluxate and/or incomplete response to medical or surgical therapy.

With the use of markers for acute and chronic inflammation, we also had the opportunity to describe, in relative terms, the tissue stress and possible mucosal quiescence associated with the respective therapeutic interventions. It has been hypothesized that refluxed gastric juice might not damage the esophagus directly, but rather incite a cytokine-mediated inflammatory response that ultimately causes esophageal damage[30]. As a response to therapy, with no difference between the two study groups, we found a steady decline in the scoring of neutrophils and mononuclear cells both in the columnar lined and squamous epithelia. Notably, normal findings were not observed at any location. These parameters have not previously been studied in long-segment BE patients and therefore it is unclear what relevance these observations may have on e.g., chronic GERD as such. In addition, other factors may well affect the inflammatory changes at baseline, as well as in response to therapy in BE, such as the length and intensity of previous therapies.

Other markers of reflux-induced damage to the squamous epithelium are represented by the papillary length, basal cell layer thickness and the width of the intercellular spaces. These variables have not previously been studied in the most distal squamous epithelium of long-segment BE patients. We observed only a marginal effect of therapy in the direction towards normalization, but obviously these changes are different from what has been demonstrated to occur in response to PPI therapy in the distal esophagus of GERD patients[31]. It might be argued that baseline data were captured after a too limited period of time for duodeno-gastro-esophageal reflux to exert its full damaging effect. However, basically all similar studies have applied a corresponding or even shorter washout period[19,32,33]. Of note, the anti-reflux-operated patients had surgery more than 5 years before, but still displayed the same outcomes as those allocated to increasing doses of PPI.

In conclusion, intraesophageal acid reflux variables co-vary with the symptom scores in patients with long-segment BE throughout the upwards titration of PPI doses until normalization of acid reflux. Inflammation and GERD-specific morphological markers improved somewhat along PPI optimisation, to the level seen after a clinically well-functioning anti-reflux valve. Similar observations were not detectable regarding tissue differentiation and proliferation, neither in the columnar lined nor in the squamous epithelium.

In clinical practice, the management of Barrett’s esophagus (BE) patients is based on a pragmatic symptom-control approach where the dose of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) is adjusted to the level of symptom control. The aims of the present study were: (1) to determine whether the acid reflux variables co-varied with the symptom scores throughout the upward titration of the respective PPI doses; (2) to ascertain whether it is possible to eradicate acid reflux in these patients; (3) to determine if tailored medical therapy can reach the same level of reflux and symptom control as a successful anti-reflux surgery; and (4) to evaluate histological changes in the esophageal mucosa in response to suppression of acidic reflux.

Actually, there is still controversy on the role of PPI in BE patients and limited information of the impact of anti-reflux surgery in these patients. This study aims to address those issues.

Most BE patients achieved complete acid suppression under PPI therapy. Acid suppression was associated with an improvement in symptom score in patients on PPI and after effective anti-reflux surgery. There was no correlation between each increase in PPI dose, symptom improvement and changes in esophageal pH. Supression of acidic reflux was associated with limited improvements in esophageal histology.

Based on the results of this prospective study, clinicians may estimate the impact of increasing doses of PPI or anti-reflux surgery in their BE patients.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease-health related quality of life refers to gastroesophageal reflux disease health related quality of life questionnaire that is used to access quantitatively the symptom severity in gastroesophageal reflux disease and its impact in daily activities.

The Swedish group present a manuscript on a prospective comparison between a group of patients under medical treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease with progressive doses of PPI until normal acid exposure is achieved and a group of asymptomatic patients after a fundoplication.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Sweden

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Herbella FAM, Misiakos EPP, Thota PN S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K, Ang Y, Kang JY, Watson P, Trudgill N, Patel P, Kaye PV, Sanders S. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2014;63:7-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1016] [Cited by in RCA: 875] [Article Influence: 79.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gutschow CA, Bludau M, Vallböhmer D, Schröder W, Bollschweiler E, Hölscher AH. NERD, GERD, and Barrett’s esophagus: role of acid and non-acid reflux revisited with combined pH-impedance monitoring. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:3076-3081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McQuaid KR, Laine L, Fennerty MB, Souza R, Spechler SJ. Systematic review: the role of bile acids in the pathogenesis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and related neoplasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:146-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Spechler SJ, Sharma P, Souza RF, Inadomi JM, Shaheen NJ. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1084-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 382] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Basu KK, Bale R, West KP, de Caestecker JS. Persistent acid reflux and symptoms in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus on proton-pump inhibitor therapy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:1187-1192. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Spechler SJ. Does Barrett’s esophagus regress after surgery (or proton pump inhibitors)? Dig Dis. 2014;32:156-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Spechler SJ, Sharma P, Traxler B, Levine D, Falk GW. Gastric and esophageal pH in patients with Barrett’s esophagus treated with three esomeprazole dosages: a randomized, double-blind, crossover trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1964-1971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Abu-Sneineh A, Tam W, Schoeman M, Fraser R, Ruszkiewicz AR, Smith E, Drew PA, Dent J, Holloway RH. The effects of high-dose esomeprazole on gastric and oesophageal acid exposure and molecular markers in Barrett’s oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1023-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fass R, Sampliner RE, Malagon IB, Hayden CW, Camargo L, Wendel CS, Garewal HS. Failure of oesophageal acid control in candidates for Barrett’s oesophagus reversal on a very high dose of proton pump inhibitor. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:597-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Champion G, Richter JE, Vaezi MF, Singh S, Alexander R. Duodenogastroesophageal reflux: relationship to pH and importance in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:747-754. [PubMed] |

| 11. | de Bortoli N, Martinucci I, Piaggi P, Maltinti S, Bianchi G, Ciancia E, Gambaccini D, Lenzi F, Costa F, Leonardi G. Randomised clinical trial: twice daily esomeprazole 40 mg vs. pantoprazole 40 mg in Barrett’s oesophagus for 1 year. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1019-1027. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Levine DS, Haggitt RC, Blount PL, Rabinovitch PS, Rusch VW, Reid BJ. An endoscopic biopsy protocol can differentiate high-grade dysplasia from early adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:40-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Silva FB, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Vieth M, Rabenstein T, Goda K, Kiesslich R, Haringsma J, Edebo A, Toth E, Soares J. Endoscopic assessment and grading of Barrett’s esophagus using magnification endoscopy and narrow-band imaging: accuracy and interobserver agreement of different classification systems (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:7-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Velanovich V. The development of the GERD-HRQL symptom severity instrument. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:130-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zerbib F, des Varannes SB, Roman S, Pouderoux P, Artigue F, Chaput U, Mion F, Caillol F, Verin E, Bommelaer G. Normal values and day-to-day variability of 24-h ambulatory oesophageal impedance-pH monitoring in a Belgian-French cohort of healthy subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:1011-1021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fiocca R, Mastracci L, Riddell R, Takubo K, Vieth M, Yerian L, Sharma P, Fernström P, Ruth M. Development of consensus guidelines for the histologic recognition of microscopic esophagitis in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: the Esohisto project. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:223-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dixon MF. Gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia: Vienna revisited. Gut. 2002;51:130-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 445] [Cited by in RCA: 498] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vieth M, Kushima R, Mukaisho K, Sakai R, Kasami T, Hattori T. Immunohistochemical analysis of pyloric gland adenomas using a series of Mucin 2, Mucin 5AC, Mucin 6, CD10, Ki67 and p53. Virchows Arch. 2010;457:529-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yachimski P, Maqbool S, Bhat YM, Richter JE, Falk GW, Vaezi MF. Control of acid and duodenogastroesophageal reflux (DGER) in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1143-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fiocca R, Mastracci L, Engström C, Attwood S, Ell C, Galmiche JP, Hatlebakk J, Junghard O, Lind T, Lundell L. Long-term outcome of microscopic esophagitis in chronic GERD patients treated with esomeprazole or laparoscopic antireflux surgery in the LOTUS trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1015-1023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wetscher GJ, Gadenstaetter M, Klingler PJ, Weiss H, Obrist P, Wykypiel H, Klaus A, Profanter C. Efficacy of medical therapy and antireflux surgery to prevent Barrett’s metaplasia in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Surg. 2001;234:627-632. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Galmiche JP, Hatlebakk J, Attwood S, Ell C, Fiocca R, Eklund S, Långström G, Lind T, Lundell L. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery vs esomeprazole treatment for chronic GERD: the LOTUS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305:1969-1977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ouatu-Lascar R, Triadafilopoulos G. Complete elimination of reflux symptoms does not guarantee normalization of intraesophageal acid reflux in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:711-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kastelein F, Spaander MC, Steyerberg EW, Biermann K, Valkhoff VE, Kuipers EJ, Bruno MJ. Proton pump inhibitors reduce the risk of neoplastic progression in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:382-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jonnalagadda S. Anti-reflux surgery for Barrett’s esophagus? Gastroenterology. 2004;126:610-611. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Singh S, Garg SK, Singh PP, Iyer PG, El-Serag HB. Acid-suppressive medications and risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2014;63:1229-1237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hao Y, Sood S, Triadafilopoulos G, Kim JH, Wang Z, Sahbaie P, Omary MB, Lowe AW. Gene expression changes associated with Barrett’s esophagus and Barrett’s-associated adenocarcinoma cell lines after acid or bile salt exposure. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mastracci L, Grillo F, Zentilin P, Spaggiari P, Dulbecco P, Pigozzi S, Savarino V, Fiocca R. Cell proliferation of squamous epithelium in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: correlations with clinical, endoscopic and morphological data. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:637-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sikkema M, Kerkhof M, Steyerberg EW, Kusters JG, van Strien PM, Looman CW, van Dekken H, Siersema PD, Kuipers EJ. Aneuploidy and overexpression of Ki67 and p53 as markers for neoplastic progression in Barrett’s esophagus: a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2673-2680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Dunbar KB, Agoston AT, Odze RD, Huo X, Pham TH, Cipher DJ, Castell DO, Genta RM, Souza RF, Spechler SJ. Association of Acute Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease With Esophageal Histologic Changes. JAMA. 2016;315:2104-2112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Stolte M, Vieth M, Schmitz JM, Alexandridis T, Seifert E. Effects of long-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease on the histological findings in the lower oesophagus. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:1125-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Gerson LB, Mitra S, Bleker WF, Yeung P. Control of intra-oesophageal pH in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus on omeprazole-sodium bicarbonate therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:803-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | De Jonge PJ, Siersema PD, Van Breda SG, Van Zoest KP, Bac DJ, Leeuwenburgh I, Ouwendijk RJ, Van Dekken H, Kusters JG, Kuipers EJ. Proton pump inhibitor therapy in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease decreases the oesophageal immune response but does not reduce the formation of DNA adducts. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:127-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |