Published online May 7, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i17.3077

Peer-review started: December 16, 2016

First decision: January 19, 2017

Revised: January 20, 2017

Accepted: March 31, 2017

Article in press: March 31, 2017

Published online: May 7, 2017

Processing time: 142 Days and 23.3 Hours

To compare surgical and oncological outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) in patients ≥ 75 years of age with two younger cohorts of patients.

The prospectively maintained Institutional database of pancreatic resection was queried for patients aged ≥ 75 years (late elderly, LE) submitted to PD for any disease from January 2010 to June 2015. We compared clinical, demographic and pathological features and survival outcomes of LE patients with 2 exact matched cohorts of younger patients [≥ 40 to 64 years of age (adults, A) and ≥ 65 to 74 years of age (young elderly, YE)] submitted to PD, according to selected variables.

The final LE population, as well as the control groups, were made of 96 subjects. Up to 71% of patients was operated on for a periampullary malignancy and pancreatic cancer (PDAC) accounted for 79% of them. Intraoperative data (estimated blood loss and duration of surgery) did not differ among the groups. The overall complication rate was 65.6%, 61.5% and 58.3% for LE, YE and A patients, respectively, P = NS). Reoperation and cardiovascular complications were significantly more frequent in LE than in YE and A groups (P = 0.003 and P = 0.019, respectively). When considering either all malignancies and PDAC only, the three groups did not differ in survival. Considering all benign diseases, the estimated mean survival was 58 and 78 mo for ≥ and < 75 years of age (YE + A groups), respectively (P = 0.012).

Age is not a contraindication for PD. A careful selection of LE patients allows to obtain good surgical and oncological results.

Core tip: Age ≥ 75 years is not a contraindication for pancreaticoduodenectomy. The selection of patients is of utmost importance to obtain the best surgical and oncological results. Our analysis demonstrated that post-operative results are similar in patients aged ≥ and < 75 years of age.

- Citation: Paiella S, De Pastena M, Pollini T, Zancan G, Ciprani D, De Marchi G, Landoni L, Esposito A, Casetti L, Malleo G, Marchegiani G, Tuveri M, Marrano E, Maggino L, Secchettin E, Bonamini D, Bassi C, Salvia R. Pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients ≥ 75 years of age: Are there any differences with other age ranges in oncological and surgical outcomes? Results from a tertiary referral center. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(17): 3077-3083

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i17/3077.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i17.3077

Aging is a natural process and the number of elderly is rapidly growing in western countries. It has been estimated that Americans elderly are the fastest growing age group and that they will become more than a fifth of the whole population by 2030[1]. Hence, age-related chronic and neoplastic disease will be diagnosed always more frequently[2]. Pancreatic surgeons face daily with elderly patients. More than 60% of patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer (PDAC) is ≥ 65 years[3,4]. In addition, PDAC is one of those cancers that will experience a 55% increase in diagnosis by 2030[5].

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is still burdened by high rates of morbidity and mortality, ranging from 35%-51% and 1%-6%, respectively[6-8].

Giving the unpredictable impact of aging on morbidity and mortality and considering the potentially higher risks of developing age-related complications[9,10], the decision to submit elderly to a PD can be challenging.

Two aspects should always be considered before submitting the elderly to a PD, first, for benign diseases, the post-operative recovery and the long-term quality of life; second, for malignancies, the fact that the elderly are less likely to receive proper adjuvant chemotherapy and this could make surgery less effective[11].

The aim of this study was to analyze the outcomes of PD on a population of elderly (≥ 75 years of age) and to compare them with 2 matched cohorts of younger patients (≥ 65 and < 75 of age and ≥ 40 and < 65 of age), to determine whether differences on surgical and oncological outcomes can be found in the index population.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: The index population for this study was obtained from the electronic Institutional prospectively maintained database of patients submitted to pancreatic resections at the General and Pancreatic Surgery Department of the University of Verona, Verona, Italy. The database was queried for all patients ≥ 75 years of age (late elderly, LE) submitted to PD for any disease from January 2010 to June 2015 (n = 123). Then the database was queried for all patients who underwent PD for any condition with an age between 40 and 64 years (adults, A) and from 65 to 74 years (young elderly, YE) over the same period. The latter two were the groups from whom the matched cohorts have been extracted. Patients submitted to PD with vascular resection were excluded.

Demographic, clinical, surgical, pathologic and follow-up data were retrieved from the database and from the revision of clinical records when needed. Demographic and clinical variables included age, gender, body mass index (BMI), presence of diabetes, smoking, American society of anesthesiologists (ASA) score, Age Adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Score[12], preoperative jaundice and/or biliary stent placement, serum CA 19-9 greater than 37 U/mL, neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy.

Intraoperative data included duration of surgery, estimated blood loss (EBL) and lymphoadenectomy for malignant tumors.

Postoperative data included clinically-relevant post-operative pancreatic fistula (CR-POPF, including B- and C-POPF according to ISGPF[13]), biliary fistula, drained abdominal collections, delayed gastric emptying (DGE), post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH), septic shock, surgical site infection (SSI), reoperation rate, length of stay.

Pathological data enclosed final diagnosis and nodal involvement for malignant diseases. The follow-up was performed using phone calls.

The index population of LE was compared with 2 control cohorts using a case-matching. The comparison with A and YE subjects was made using a 1:1 matching with a 0.2 caliper by the following variables: BMI, presence of diabetes (yes/no), ASA score, preoperative jaundice (yes/no), preoperative biliary stent placement (yes/no), diagnosis of malignancy, neoadjuvant therapy. To obtain 3 homogeneous groups, unmatched cases were eliminated from the index population.

Values were expressed as median and range, or percentage when appropriate. Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U-test, Kruskal-Wallis test and χ² test were used as appropriated. Overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were calculated using the method of Kaplan-Meier. When the median was not reached, the mean was used. Data were considered statistically significant for values of P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software ver.22 (IBM, Chicago, IL, United States) and Medcalc for Windows v14.8.1 (MedCalc Software, Oostend, Belgium).

Eight-hundreds sixty-seven patients were submitted to PD at the Authors Institution from January 2010 to June 2015. LE patients were originally 127 (14.6%), however, after the case-matching process 26 out 127 (20.4%) were excluded. Hence the final index population was made of 96 subjects, as well as the control groups YE and A. Table 1 outlines demographic and clinical characteristics of the 3 groups.

| Variable | LE | YE | A | P value | Total |

| Age, median (range) | 77 (75-86) | 70 (65-74) | 57 (18-64) | < 0.001 | 70 (18-86) |

| Female | 50 (52.1) | 46 (47.9) | 38 (39.6) | NS | 134 (46.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2) ± SD | 24.6 ± 3.6 | 24.9 ± 3.4 | 24.5 ± 4.2 | NS | |

| Smoking | 37 (50.0) | 28 (37.5) | 17 (23.6) | 0.004 | 82 (28.5) |

| Diabetes | 21 (21.9) | 16 (16.7) | 22 (22.9) | NS | 59 (20.5) |

| Jaundice | 68 (70.8) | 66 (68.8) | 65 (67.7) | NS | 199 (69.1) |

| CA 19-9 > 37 mU/L (malignancies) | 29 (30.2) | 37 (38.5) | 43 (44.8) | NS | 109 (37.8) |

| ASA score, mean (range) | 2 (2-3) | 2 (2-4) | 2 (1-3) | NS | 2 (1-4) |

| AA-Charlson Score, mean (range) | 6 (3-10) | 5 (3-9) | 4 (0-8) | NS | 5 (0-10) |

| Harvested lymph-nodes, mean | 24 | 26 | 26 | NS | |

| Pre-operative biliary drain | 49 (51.0) | 53 (55.2) | 48 (50.0) | NS | 150 (52.1) |

| Malignant diagnosis | 68 (70.8) | 67 (69.8) | 68 (70.8) | NS | 203 (70.4) |

| N1 status | 41 (60.2) | 42 (62.6) | 42 (61.8) | NS | 125 (61.5) |

| Neoadjuvant therapy, (PDAC) | 10 (20.4) | 11 (23.0) | 10 (18.5) | NS | 31 (20.6) |

| Adjuvant therapy, yes (all malignancies) | 34, | 29, | 29, | NS | 92 (45.3) |

| n = 57 (68) | n = 45 (65) | = 45 (64.4) | NS | 147 (70.3) |

Intraoperative data (EBL and length of stay) did not show any statistically significant difference among the groups (350, 340 and 300 mL; 362, 372 and 383 min for LE, YE and A, respectively). The mean number of harvested lymph-nodes was 24, 26 and 26 for LE, YE and A groups, respectively (P = NS).

The distribution of benign and malignant diagnoses was homogeneous among the 3 groups. Table 2 reports the detail of the diagnoses. About 70% of patients were submitted to surgery for malignant periampullary tumors. Within the malignant lesions, PDAC was the most frequent diagnosis (up to 79%). Among the benign tumors, PD was more frequently performed due to cystic tumors.

| Diagnosis | Group LE | Group YE | Group A | P value |

| Malignant tumors | 68 (71) | 67 (70) | 68 (71) | NS |

| PDAC | 49 (51) | 47 (49) | 54 (56) | NS |

| Ampullary carcinoma | 12 (12) | 10 (10) | 8 (8) | NS |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 3 (3) | 5 (5) | 1 (1) | NS |

| Clear cell renal carcinoma | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | NS |

| Duodenal carcinoma | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | NS |

| Others | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 0 | NS |

| Benign conditions | 28 (29) | 29 (30) | 28 (29) | NS |

| Cystic tumors | 16 (17) | 18 (19) | 10 (10) | NS |

| pNET | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | 5 (5) | NS |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 0 | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | NS |

| GIST | 1 (1) | 0 | 2 (2) | NS |

| Others | 7 (7) | 3 (3) | 7 (7) | NS |

| Total | 96 (100) | 96 (100) | 96 (100) | NA |

Table 3 shows post-operative complications reported for the 3 groups. The overall morbidity rate was not significantly different among the 3 groups (65.6% vs 61.5% vs 58.3%, P = NS). The reoperation rate was the only surgical complication significantly more frequent in LE (16.7% vs 4.3% vs 5.2%, P = 0.003). This significance was even higher when LE were compared with patients aged < 75 years (YE + A groups, 16.7% vs 4.7%, P = 0.001). The commonest causes of reoperation were bleeding (9, 56%) and septic shock (5, 31.2%). Considering medical complications after surgery, a higher incidence of cardiovascular complications (mostly episodes of atrial fibrillation) was reported (P = 0.019). Only 1 post-operative death was reported in the LE group, due to septic shock after a C-POPF.

| Variable | Group LE | Group YE | Group A | P value | Total |

| CR-POPF | 30 (31.3) | 26 (27.1) | 26 (27.1) | NS | 82 (28.4) |

| Biliary fistula | 8 (8.3) | 6 (6.3) | 4 (4.2) | NS | 18 (6.2) |

| Abdominal collections | 37 (38.5) | 30 (31.3) | 32 (33.3) | NS | 99 (34.3) |

| DGE | 17 (17.7) | 9 (9.4) | 9 (9.4) | NS | 35 (12.1) |

| PPH | 19 (20.2) | 16 (16.7) | 13 (13.5) | NS | 48 (16.7) |

| Sepsis | 30 (35.3) | 27 (31.4) | 20 (25.0) | NS | 77 (30.7) |

| Surgical site infection | 18 (22.8) | 16 (20.5) | 13 (17.1) | NS | 47 (20.2) |

| Reoperation | 16 (16.7) | 4 (4.2) | 5 (5.3) | 0.003 | 25 (8.7) |

| LoS (d), mean (range) | 10 (5-73) | 10 (6-127) | 12 (6-155) | NS | 11 (5-155) |

| ARF | 8 (8.3) | 4 (4.1) | 1 (1) | NS | 13 (4.5) |

| Pulmonary complications | 32 (33.3) | 27 (28.1) | 25 (26) | NS | 84 (29.1) |

| CV complications | 16 (16.7) | 6 (6.3) | 6 (6.3) | 0.019 | 28 (9.7) |

| Overall1 | 63 (65.6) | 59 (61.5) | 56 (58.3) | NS | 178 (61.8) |

| 90-d mortality | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | 1 (0.03) |

The mean follow-up was 32, 33 and 34 mo for LE, YE and A group, respectively (P = NS). Considering all diagnosis (benign and malignant) and grouping YE and A groups, median survival was 53 mo for ≥ 75 years of age vs 71 mo for < 75 years of age (P = 0.09). Stratifying the analysis for benign diseases only, we report an estimated mean survival of 70 mo. Patients ≥ 75 and < 75 years of age showed an estimated mean survival of 58 and 78 mo, respectively (P = 0.012). Senescence (n = 1) and cardiovascular problems (n = 3) were responsible for the 4 deaths reported within the LE group. On the contrary, no deaths were reported in the control groups after PD for benign conditions.

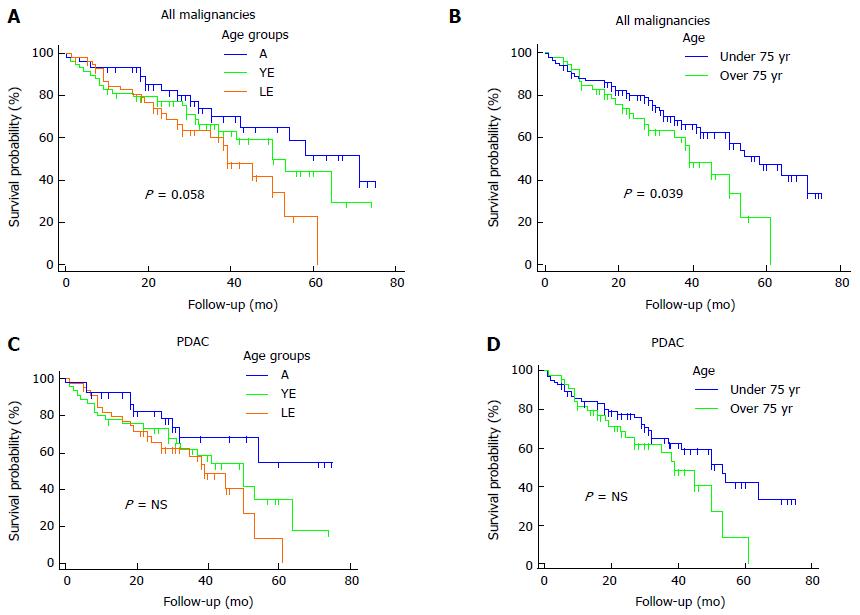

Regarding malignant diagnoses, the overall median survival was 53 mo. LE, YE and A patients showed a median survival of 39, 50 and 71 mo, respectively (P = 0.058, Figure 1A). Comparing patients < 75 and ≥ 75 years of age we reported a median overall survival of 39 and 58 mo, respectively (P = 0.036, Figure 1B).

A sub-analysis for PDAC showed a median overall survival of 50 mo. LE patients revealed a mean survival of 36 mo, vs 43 mo and 54 mo of YE and A groups, respectively (P = NS). The overall 5-year survival was 33.9%, whereas, the 5-year survival of LE, YE and A groups was 13.5%, 35% and 54.6%, respectively, Figure 1C). Patients aged ≥ and < 75 years showed a median survival of 39 and 53 mo, respectively (P = NS; Figure 1D).

No differences in survival within the LE were found at the univariate analysis by the following variables: sex (male/female), CA 19-9 levels > 37 mU/L (yes/no), diabetes (yes/no), jaundice (yes/no), complicated course (yes/no), CR-POPF (yes/no), reoperation (yes/no), biliary fistula (yes/no), abdominal collections (yes/no), N1 (yes/no).

The elderly population is increasing worldwide. In parallel, the rate of chronic and neoplastic diseases is rising steeply. PDAC, for whom aging is an independent risk factor[1], is one of those malignant neoplasms that will be diagnosed more frequently in the next decades[5]. In addition, the application of extensive cross-sectional imaging has led to an incredibly high prevalence of cystic pancreatic lesions[14], even in elderly. Thus, PD is always more frequently performed on elderly patients. In developed countries, the accepted definition of elderly population is of subjects ≥ 65 years of age. This cut-off considers social, cultural and working aspects. However, the biological status cannot be defined by a number and the decision to submit to surgery elderly patients must be weighed over the risks considering multiple factors (comorbidities, performance status, patient choice, home assistance, life expectancy).

Intraoperative data did not show any statistical difference in terms of duration of surgery, EBL and extent of lymphadenectomy. Based on this, we can claim that the surgical technique was not different in LE patients report an estimated mean survival of 70 mo. Patients ≥ 75 and < 75 years of age showed an estimated mean survival of 58 and 78 mo, respectively (P = 0.012). Senescence (n = 1) and cardiovascular problems (n = 3) were responsible for the 4 deaths reported within the LE group. On the contrary, no deaths were reported in the control groups after PD for benign conditions.

Considering overall post-operative complications, our data do not confirm previous findings of an overall higher incidence of complications in the elderly population[3,5-7,15-19]. In fact, the overall morbidity rate was homogeneous among the 3 groups. Interestingly, analyzing each complication considered, even the most fearsome such as PPH, CR-POPF, septic shock, there was not a statistically higher incidence in the LE group. However, the reoperation rate, of whom PPH, CR-POPF and septic shock are usually cause of, was statistically higher in the LE group (P = 0.003). Several considerations could explain this finding. First, the surgeon could unconsciously and paradoxically tend to be more aggressive with an elderly patient in the treatment of severe complications requiring surgery, hypothesizing functional reserves insufficient to allow for a conservative management of these complications. Second, in case of post-operative complications, pre-existent cardiopulmonary and vascular comorbidities typical of LE could precipitate the clinical conditions leading to reoperation. Third, the advanced age is associated with a higher risk of bacteremia[20], a condition that increases independently the risk of septic complications after PD[21]. When considering medical complications, the higher rate of cardiovascular problems registered in LE patients let us speculate that probably a dedicated perioperative fluid intervention with a negative fluid balance would prevent the onset of such disorders in this subset of patients.

Data regarding oncological outcomes after pancreatic surgery for malignancies in the elderly are controversial so far. Some Authors report that the elderly population shows a worse outcome[15,22] however other research groups did not find any significant survival difference[4,23]. This heterogeneity of results is probably due to selection biases.

In the present study, pooling all malignant tumors, the survival analysis revealed that LE patients had a trend towards a worse outcome compared with the other 2 groups, even if this was not statistically significant. However, the statistical significance was reached when LE patients were compared with the YE + A patients (P = 0.036), demonstrating that probably a larger sample size would have reach the statistical significance.

Stratifying the survival analysis for PDAC, LE patients, again, showed a trend towards a worse survival, however this data was not statistically significant, even comparing with the YE + A group. In our opinion, the most surprising data is the good overall survival reported for LE patients and the homogeneous distribution either of the different malignant diagnoses and the stage of the disease for PDAC among the 3 groups gives strength to this finding.

This finding is not surprising, since several factors can worsen the oncological outcomes in the elderly, such as a physiologic shorter life expectancy, pre-existent comorbidities that reduce functional reserves, worse post-discharge home care and rehabilitation services and a more difficult access to adjuvant therapy. In particular, a retrospective analysis by Sehgal et al[24] demonstrated that elderly patients receive less frequently adjuvant treatments after pancreatic surgery than younger patients, even if they obtain the same oncological benefits.

A separate mention should be made for survival data when PD was carried out for benign lesions. LE patients had a worse survival outcome if compared with < 75 years of age (57 mo vs 78 mo, respectively, P = 0.012). However, the small sample size and the fact the most of deaths were due to cardiovascular reasons, does not allow us to speculate that surgery could have somehow worsen or make evident pre-existent comorbidities leading to death. Nevertheless, it should always keep in mind that long-term postoperative consequences of PD, such as exocrine pancreatic insufficiency with malabsorption and loss of weight, new onset or worsening of pre-existent diabetes and alteration in diet, are managed with more difficulty by LE patients than by younger patients. In addition, LE patients often live alone because of widowhood and the adherence and medication management could be insufficient.

Our results strengthen the idea that advanced age does not represent per sé a contraindication for PD and, in general, for pancreatic surgery. However, considering the higher rates of reoperation and cardiovascular complications found in LE patients we can claim that this subgroup of patients shows a latent frailty that requires a global careful attention, to prevent the development of life-threatening complications. On the other side, present survival data for LE patients demonstrate that submitting to a PD a LE patient for a periampullary malignant tumor is at least “worthwhile”.

This study has biases that must be considered, such as the retrospective nature, the lack of data about the number of LE patients who did not receive surgery due to comorbidities or to patient refusal, the lack of data regarding the performance status of LE patients, the high number of missing data about adjuvant therapy. In addition, our population of LE patients was well-selected (as demonstrated by the median ASA score of 2) and we probably submitted to PD the most fit LE. At the same time, the strength of this research is the case-matching with 2 different cohorts, that allowed us to give weight to advanced age as independent variable.

In conclusion, the advanced age is not an independent contraindication to PD. A fit for surgery group of LE patients can be submitted to PD safely and fruitfully. Even more caution should be used when surgery is indicated for benign conditions, where life expectancy is higher.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is always more frequently performed on elderly patients.

This study explores surgical and oncological outcomes of PD in a population of late elderly (LE, > 75 years of age) patients, comparing them with 2:1:1 matched cohorts of younger patients, adults (A, ≥ 40 to 64 years of age) and young elderly (YE, ≥ 65 to 74 years of age).

The overall complication rate was homogeneous among the three groups. LE showed statistically higher rates of reoperation and cardiovascular complications compared to YE and A patients. Considering all malignancies LE showed slightly worse results only when YE and A groups were grouped (P = 0.039). Stratifying the analysis for pancreatic cancer, LE showed statistically similar results of YE and A groups.

This study suggests that PD can be performed safely and worthily on selected LE patients.

This is very interesting study which is well designed. Agree with the authors that the age of the patient is becoming less important in the indication of large surgery but a very stricted evaluation of quality of life must be performed in order to evaluate the benefit-risk of these patients.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Golffier C, Isaji S, Li J S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Etzioni DA, Liu JH, Maggard MA, Ko CY. The aging population and its impact on the surgery workforce. Ann Surg. 2003;238:170-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in RCA: 564] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in RCA: 25541] [Article Influence: 1824.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 3. | Sukharamwala P, Thoens J, Szuchmacher M, Smith J, DeVito P. Advanced age is a risk factor for post-operative complications and mortality after a pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis and systematic review. HPB (Oxford). 2012;14:649-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hatzaras I, George N, Muscarella P, Melvin WS, Ellison EC, Bloomston M. Predictors of survival in periampullary cancers following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:991-997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Khan S, Sclabas G, Lombardo KR, Sarr MG, Nagorney D, Kendrick ML, Donohue JH, Que FG, Farnell MB. Pancreatoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma in the very elderly; is it safe and justified? J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1826-1831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pratt WB, Gangavati A, Agarwal K, Schreiber R, Lipsitz LA, Callery MP, Vollmer CM. Establishing standards of quality for elderly patients undergoing pancreatic resection. Arch Surg. 2009;144:950-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Balcom JH, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL, Chang Y, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Ten-year experience with 733 pancreatic resections: changing indications, older patients, and decreasing length of hospitalization. Arch Surg. 2001;136:391-398. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Bentrem DJ, Yeh JJ, Brennan MF, Kiran R, Pastores SM, Halpern NA, Jaques DP, Fong Y. Predictors of intensive care unit admission and related outcome for patients after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:1307-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vollmer CM, Pratt W, Vanounou T, Maithel SK, Callery MP. Quality assessment in high-acuity surgery: volume and mortality are not enough. Arch Surg. 2007;142:371-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vanounou T, Pratt W, Fischer JE, Vollmer CM, Callery MP. Deviation-based cost modeling: a novel model to evaluate the clinical and economic impact of clinical pathways. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:570-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nagrial AM, Chang DK, Nguyen NQ, Johns AL, Chantrill LA, Humphris JL, Chin VT, Samra JS, Gill AJ, Pajic M. Adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients with pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:313-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chang CM, Yin WY, Wei CK, Wu CC, Su YC, Yu CH, Lee CC. Adjusted Age-Adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index Score as a Risk Measure of Perioperative Mortality before Cancer Surgery. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3282] [Cited by in RCA: 3512] [Article Influence: 175.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 14. | de Jong K, Nio CY, Hermans JJ, Dijkgraaf MG, Gouma DJ, van Eijck CH, van Heel E, Klass G, Fockens P, Bruno MJ. High prevalence of pancreatic cysts detected by screening magnetic resonance imaging examinations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:806-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 367] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Makary MA, Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Chang D, Cunningham SC, Riall TS, Yeo CJ. Pancreaticoduodenectomy in the very elderly. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:347-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kow AW, Sadayan NA, Ernest A, Wang B, Chan CY, Ho CK, Liau KH. Is pancreaticoduodenectomy justified in elderly patients? Surgeon. 2012;10:128-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | de la Fuente SG, Bennett KM, Pappas TN, Scarborough JE. Pre- and intraoperative variables affecting early outcomes in elderly patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford). 2011;13:887-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Melis M, Marcon F, Masi A, Pinna A, Sarpel U, Miller G, Moore H, Cohen S, Berman R, Pachter HL. The safety of a pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients older than 80 years: risk vs. benefits. HPB (Oxford). 2012;14:583-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee DY, Schwartz JA, Wexelman B, Kirchoff D, Yang KC, Attiyeh F. Outcomes of pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic malignancy in octogenarians: an American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program analysis. Am J Surg. 2014;207:540-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Girard TD, Opal SM, Ely EW. Insights into severe sepsis in older patients: from epidemiology to evidence-based management. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:719-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Costi R, De Pastena M, Malleo G, Marchegiani G, Butturini G, Violi V, Salvia R, Bassi C. Poor Results of Pancreatoduodenectomy in High-Risk Patients with Endoscopic Stent and Bile Colonization are Associated with E. coli, Diabetes and Advanced Age. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:1359-1367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Riall TS. What is the effect of age on pancreatic resection? Adv Surg. 2009;43:233-249. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Oguro S, Shimada K, Kishi Y, Nara S, Esaki M, Kosuge T. Perioperative and long-term outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy in elderly patients 80 years of age and older. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398:531-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sehgal R, Alsharedi M, Larck C, Edwards P, Gress T. Pancreatic cancer survival in elderly patients treated with chemotherapy. Pancreas. 2014;43:306-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |