INTRODUCTION

The term esophagitis refers to an inflammatory condition of the esophageal mucosa, usually associated with characteristic symptoms, such as heartburn, chest pain and dysphagia. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the main cause of esophagitis. It affects about 20% of the population in Western countries[1] and represents one of the most common conditions which gastroenterologists and general practitioners have to deal with. In fact the esophageal wall has low defense against gastric acid injury that can induce either erosive or non-erosive esophagitis[2]. Over the years esophagitis was considered almost synonymous with acid reflux, which lead to consequent therapeutic approaches mainly aimed at reducing gastric secretion. Today other mechanisms are known to similarly affect the esophageal wall and its motor function. These conditions are less frequent than GERD but they should also be taken into consideration when managing patients with unexplained upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Some of these are immune-mediated inflammatory processes, either limited to the esophageal wall [like eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE)] or part of systemic alterations [like Crohn’s disease (CD)]. Other possible causes of esophagitis include infectious agents and corrosive substances causing damage to the esophageal mucosa or injures related to chemiotherapy and/or radiotherapy.

EoE

EoE is an immune-mediate inflammatory disease characterized by an eosinophilic infiltration of the esophageal mucosal layer [≥ 15 eosinophils in at least one high-power field (HPF) found in one or more of the esophageal mucosa biopsies[3]]. This condition was first described in the 70s’[4] but became a distinct clinical entity in the early 1990s’[5]. Over the last ten years, there has been a significant increase in the number of cases of EoE, with an actual estimated incidence of 7/100000 per year and a prevalence of 43/100000 per year[6]. The most common symptom referred by patients with EoE is dysphagia, usually with solid foods, that can also cause esophageal food bolus impaction (OFBI). In fact, it has been recently demonstrated that about 30% of OFBI referred to an Emergency Department is likely to be related to EoE, rather than to other organic diseases such as neoplasms or Schatzki rings[7]. Symptoms usually start in childhood, particularly when there is a family history of allergy. Sometimes the early symptoms can mimic GERD with dysphagia (in fact food impaction usually occur in later stages); in other cases the food impaction can be the first clinical manifestation that leads to the diagnosis. Upper GI endoscopy performed in the first years of the disease can show normal findings, especially in pediatric patients, but can reveal some characteristic patterns in adults. In fact, the esophageal wall presents multiple rings resembling the trachea (so called “trachealization of the esophagus”, Figure 1) or longitudinal furrows through the entire lumen, which often represent the areas with greater eosinophilic infiltration[8,9]. The progressive loss of tissue elasticity due to the inflammatory cell infiltration can elicit motor abnormalities, which may become more evident when the inflammatory process reaches the muscular or neuronal site. Although no specific motor alterations allow the physician to make the diagnosis of EoE, recent evaluations using high-resolution manometry[10] identify frequent alterations of the intraesophageal pressurization in EoE patients. The most characteristic feature is an early pan-esophageal pressurization preceding the peristaltic wave, as a possible consequence of the decreased esophageal wall compliance. Other dysmotility aspects, such as weak or failed peristalsis, occur with similar incidence in EoE and GERD patients, explaining the potential clinical overlap between the two conditions, at least in the early stages. Such intriguing features of EoE reflect a variety of therapeutic strategies, which are not fully standardized yet. Until recently, EoE and GERD were considered two distinct entities based on the lack of response to proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)[11] and, with less relevance, on a normal 24-h pH profile[12]. In the last years a surprising third category of EoE with clinical and histological improvement after PPIs has been identified[13]. The mechanism through which PPIs can be effective in EoE is not clear, but may be related to their potential antioxidant activity and capacity to reduce inflammatory cytokines production[14]. In summary, three distinct entities should be considered: GERD, PPI-responsive EoE and EoE[15]. The first two of these respond to inhibition of gastric secretion either directly or in combination with dietetic restrictions, whereas the latter requires to reduce the immune response by topical steroids and change in the alimentary habits. The high incidence of GERD and its possible overlap with EoE[16] still represent a confounding factor in differentiating these two entities. Nevertheless, it is important to consider EoE in the diagnostic protocol of patients, especially young adults, who are scarcely responsive to the common anti-reflux strategies. In particular, once an upper GI endoscopy is performed in such patients, biopsies are mandatory.

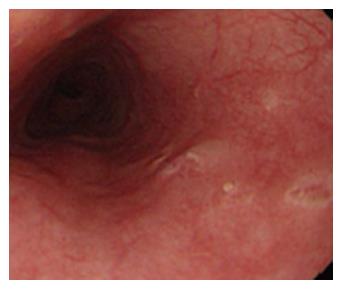

Figure 1 Eosinophilic esophagitis.

Endoscopic appearance of eosinophilic esophagitis; note the characteristic multiple rings throughout the esophagus resembling the tracheal aspect and described as “trachealization of the esophagus”. This finding is not common in the early stage of the disease, when tissue elasticity is still preserved by the inflammatory damage.

ESOPHAGEAL INVOLVEMENT IN CD

CD is an inflammatory bowel disease that can affect the entire GI tract. The most common sites of CD are the terminal ileum and colon but inflammation may be less frequently found also in the more proximal areas. Esophageal involvement in concomitant ileocolonic disease occurs in 0.2%-3% of the adult population, whereas isolated esophageal CD has been rarely reported[17]. Similarly to the classical ileocolonic CD, endoscopic appearance of the esophagus is characterized by aphthous erosions and ulcerations usually localized far from esophago-gastric junction (Figure 2), which helps to differentiate them from GERD, nodularity, strictures[18] and the possibility of fistula occurring between esophagus and mediastinum, pleural cavity or bronchus[19]. Symptoms can range from a mild dysphagia to a severe obstructive condition depending on the grade of parietal involvement. Although histology identifies the typical features of CD (e.g., non-caseating granulomas) in about half of gastric and duodenal involvement, esophageal findings consistent with CD are reported in only 10% of cases[20].

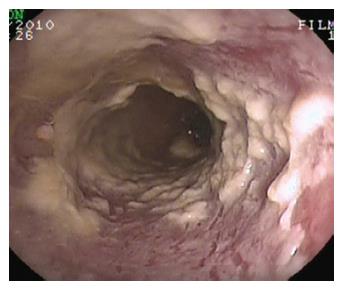

Figure 2 Esophageal Crohn’s disease.

Endoscopic finding in a patient with esophageal localization of Crohn’s disease. Note the apthous erosions and the small ulceration similar to those usually present in the lower gastrointestinal tract. The localization at the middle tract of the esophagus, far from the esophago-gastric junction suggests to rule out the possibility of gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Therefore, the diagnosis of esophageal CD may not be difficult when other typical localizations are present, but it could take a long time in patients with isolated esophageal involvement.

DRUG-INDUCED ESOPHAGITIS

The damage of esophageal mucosa induced by commonly-used drugs is certainly underestimated. In fact many compounds are potentially aggressive to the esophageal wall, either by a direct toxic activity on the mucosa or by the production of caustic acidic or alkaline solutions; however the low awareness of these effects usually allows continuous assumption of the medications, with consequent more severe complications[21]. Drug-induced esophagitis is characterized by dysphagia, chest pain or odynophagia. These symptoms are generally abrupt onset, intermittent and self-limiting which can make an early diagnosis difficult. There is a lack of literature informations in this area, with data coming only from case reports or short reviews. Endoscopic findings are usually limited to the middle third of the esophagus[22], which may be compressed by the aortic arch or enlarged left atrium. The main lesions are ulcers or erosions (Figure 3); However in some cases impacted pills as well as strictures could be found. Antibiotics (doxycycline, amoxicillin, ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, rifaximin) are the major causative agents of esophagitis eliciting damage greater than NSAIDS. Other agents responsible for drug-induced esophagitis are anti-hypertensive, acetaminophen, biphosphonates, and warfarin[23]. The therapeutic approach to this type of disease is to use PPIs and antiacids, with discontinuation of the causative drug.

Figure 3 Drug-induced esophageal damage.

Endoscopic view of a patient with a history of NSAIDS use. In this case two ulcers are visible, located in the middle third of the esophagus. Also in this case, as well as for Crohn’s disease, the proximal localization makes the possibility of gastroesophageal reflux disease unlikely.

INFECTIOUS ESOPHAGITIS

Infectious diseases with esophageal involvement represent a quite uncommon condition in immunocompetent subjects. Fungi, virus and bacteria can cause esophageal damage in patients with immunodeficiency (i.e., HIV infection, history of malignancies, prolonged use of immunosuppressive drugs or steroids). Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is the main viral agent responsible for esophageal damage with endoscopic evidence of multiple shallow ulcers usually located in the lower third of the lumen. HSV esophagitis is more frequent in males than females. Symptoms are mainly odynophagia, dysphagia, and retrosternal pain, sometimes accompanied by fever[24]. Another infectious agent able to cause esophagitis is Candida. Endoscopically the esophagus shows multiple yellow plaques covering the entire tract of the esophageal wall (Figure 4) and usually localized inside the oral mucosa[25]. Patients with mycosis show dysphagia, odynophagia and, less frequently, chest pain. Bacterial esophagitis is much less common than viral and fungal infections; however Gram-positive cocci such as Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis, usually present in the oral cavity or in the upper respiratory tract, may be identified in the esophagus of immunocompromised patients[26] or in subjects receiving long-term H2 blockers or PPIs[27]. There is in fact evidence that these medications alter the microbial population facilitating infections by opportunistic agents.

Figure 4 Candida esophagitis.

Endoscopic appearance in a patient with severe dysphagia under chronic steroid treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. Note the typical multiple yellow plaques interesting the entire tract of the esophageal wall and strictly adherent to the mucosa.

When the cause of esophagitis has been identified, pathogen-specific therapy can be used. Most esophageal infections can be treated with a specific antimicrobial (e.g., fluconazole for Candida, acyclovir for Herpetic infections) associated with a therapy for the underlying immune condition.

CAUSTIC INJURY ESOPHAGITIS

Corrosive esophagitis occurs from voluntary or accidental ingestion of alkaline liquids and, less frequently, acidic substances. The effect of these two categories of agents on esophageal mucosa is different[28]. Alkaline agents cause colliquative necrosis, which leads to the destruction of mucosa within a few seconds and to thrombosis of small vessels within 48 h. Acidic substances induce coagulation necrosis with eschar formation, which may limit tissue penetration. The vast majority of alkaline agents responsible for corrosive damage are detergents; however there are other potentially aggressive substances requiring careful management[29]. One of these substances is picosulfate, commonly used as a laxative for bowel cleansing before colonoscopy. If not properly dissolved in water, picosulfate powder can cause severe injury to the esophageal wall[30]. Whatever the causative agents, mucosal damage can be assessed with endoscopy according to Zargar’s classification on a 0-3 scale, with the higher score corresponding to a worse outcome[31].

ESOPHAGITIS DUE TO CHEMO-THERAPY AND RADIO-THERAPY

Many chemotherapeutic regimens (dactinomycin, bleomycin, daunorubicin, cytarabine, 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate, vincristine) may determine the occurrence of esophageal damage, usually as a consequence of a severe oropharyngeal mucositis[32]. Thoracic irradiation may also result in significant injury to the esophageal mucosa, either by direct toxicity or by the radio-sensitizing action of previously used chemotherapics, such a doxorubicin or bleomicin. Such a damage is characterized by progressive fibrosis and degeneration of vessels, smooth muscle and neuronal component in the myenteric plexus. Endoscopically mucosal friability, edema and small erosions or large ulcers are commonly found, with stricture formation as a further complication. Dysphagia, odynophagia and chest pain may persist for weeks to months in such patients who usually require the topical application of viscous solutions containing lidocaine or steroids together with PPIs to alleviate their complains[33].

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

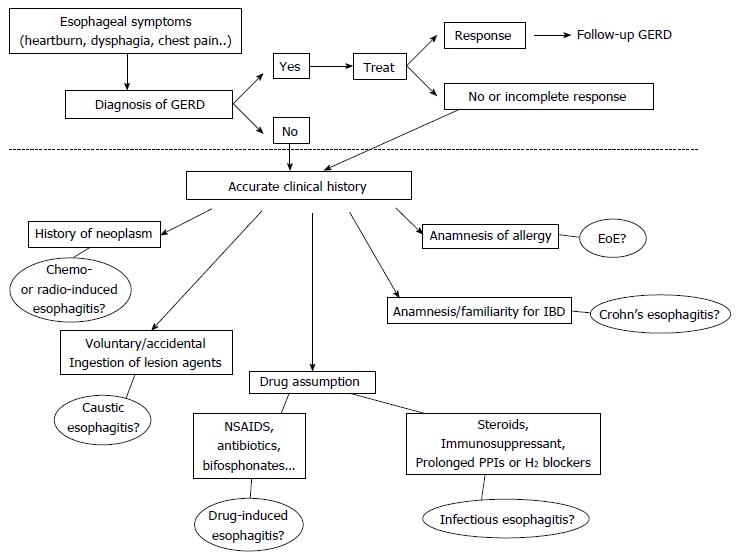

Patients with esophagitis are frequently affected by GERD, but acidic reflux is not the only aggressive phenomenon within the esophagus. Therefore all other causes of esophageal injury should be ruled out especially in subjects who do not respond to antisecretory therapy. In Figure 5 we propose a flow-chart with the possible steps to follow once ruled out the presence of Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease. Patients with a history of allergy, particularly if young, must be investigated for EoE. A previous diagnosis of IBD or underlying reumathological diseases could indicate the possibility of an esophageal involvement by CD. Patients whose immune system is impaired, because of the use of either immunosuppressant drugs or prolonged gastric antisecretory agents, may develop infectious forms of esophagitis. The drug history of each patient should always be deeply investigated, since many compounds are potentially responsible of pill-induced esophagitis. A careful anamnesis is also required to exclude damage by ingestion of caustics, either accidental or voluntary, as well as recent oncologic treatments, such as chemotherapy or radiation. The timing of symptoms onset, the site of injury and its endoscopic or radiological characteristics could further help to orientate the diagnosis.

Figure 5 Diagnostic flow-chart proposed in patients with symptoms suggestive of esophagitis (heartburn, dysphagia, chest pain and others).

The area above the dotted line includes all the possible manifestations of GERD that remains the most common etiology of symptoms. The less frequent causes are reported below the dotted line. All the possibilities deserve an accurate collection of clinical history to orientate the differential diagnosis. EoE: Eosinophilic esophagitis; NSAIDs: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Although an overlap of GERD with all the above mentioned diseases may exist, it is important to carefully evaluate all diagnostic options before making a final diagnosis. Acid is usually recognized as the ideal culprit for esophageal diseases, but sometimes it can only be an innocent by-stander and the source of disease should be sought elsewhere.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Sonia Toracchio for reviewing the English style of the manuscript.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Ierardi E S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF