Published online Apr 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i16.2972

Peer-review started: December 19, 2016

First decision: February 9, 2017

Revised: February 24, 2017

Accepted: March 30, 2017

Article in press: March 30, 2017

Published online: April 28, 2017

Processing time: 132 Days and 16.9 Hours

To determine the incidence of readmission after cholecystectomy using 90 d as a time limit.

We retrospectively reviewed all patients undergoing cholecystectomy at the General Surgery and Digestive System Service of the University Hospital of Guadalajara, Spain. We included all patients undergoing cholecystectomy for biliary pathology who were readmitted to hospital within 90 d. We considered readmission to any hospital service as cholecystectomy-related complications. We excluded ambulatory cholecystectomy, cholecystectomy combined with other procedures, oncologic disease active at the time of cholecystectomy, finding of malignancy in the resection specimen, and scheduled re-admissions for other unrelated pathologies.

We analyzed 1423 patients. There were 71 readmissions in the 90 d after discharge, with a readmission rate of 4.99%. Sixty-four point seven nine percent occurred after elective surgery (cholelithiasis or vesicular polyps) and 35.21% after emergency surgery (acute cholecystitis or acute pancreatitis). Surgical non-biliary causes were the most frequent reasons for readmission, representing 46.48%; among them, intra-abdominal abscesses were the most common. In second place were non-surgical reasons, at 29.58%, and finally, surgical biliary reasons, at 23.94%. Regarding time for readmission, almost 50% of patients were readmitted in the first week and most second readmissions occurred during the second month. Redefining the readmissions rate to 90 d resulted in an increase in re-hospitalization, from 3.51% at 30 d to 4.99% at 90 d.

The use of 30-d cutoff point may underestimate the incidence of complications. The current tendency is to use 90 d as a limit to measure complications associated with any surgical procedure.

Core tip: The use of a 30-d cutoff point to determine the rate of readmissions may underestimate the true incidence of complications. The current tendency is to use 90 d as a time limit to measure complications associated with any surgical procedure. Our objective is to determine the incidence of readmission after cholecystectomy using this longer time limit.

- Citation: Manuel-Vázquez A, Latorre-Fragua R, Ramiro-Pérez C, López-Marcano A, Al-Shwely F, De la Plaza-Llamas R, Ramia JM. Ninety-day readmissions after inpatient cholecystectomy: A 5-year analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(16): 2972-2977

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i16/2972.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i16.2972

Gallstone disease is one of the commonest digestive pathologies[1], and, as a result, cholecystectomy is one of the most frequently performed surgical procedures. Each year, more than 750000 cholecystectomies are performed in the United States[2,3] and around 48000 in the United Kingdom[4,5]. In the United States in 2004, the direct and indirect costs associated with this pathology amounted to $6.2 billion[1].

Hospital readmissions represent an important component of the associated costs of a disease and are an indicator of the quality of care. The study of the reasons for re-hospitalization may help to characterize the postoperative morbidity and costs associated with cholecystectomy, and may provide relevant data for both physicians and hospital managers[6-11]. However, few studies have evaluated the reasons for, or the rate of, readmission after cholecystectomy, and those that have done so have tended to consider the first 30 d post-surgery as the time limit[8,12,13]. This restriction may have led to an underestimation of the actual incidence of morbidity and of the socio-economic cost of the procedure[14].

Interestingly, an article published in 2011 on mortality after hepatectomy extended the cutoff point for measuring mortality from 30 to 90 d and reported a substantial increase in the rate. Since then the tendency has been to use 90 d as a limit to measure complications associated with any procedure. The objective of this study is to determine the incidence of readmission after cholecystectomy using this longer time limit and, secondarily, to analyze the reasons for re-hospitalization.

We performed a retrospective study at the General Surgery and Digestive System Service of the University Hospital of Guadalajara, which serves a health area with a resident population of 254256 inhabitants on 1 July 2015. The period analyzed was 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2015.

We included all patients undergoing cholecystectomy for biliary pathology. Hospital readmissions within 90 postoperative days were analyzed. For this purpose the Mambrino XXI® electronic medical history was used. Patients who were readmitted to any hospital service as a direct or indirect consequence of a complication of cholecystectomy within 90 d were considered as cholecystectomy-related readmissions.

Exclusion criteria for the study were ambulatory cholecystectomy, cholecystectomy combined with other procedures, oncologic disease active at the time of cholecystectomy, finding of malignancy in the resection specimen, and scheduled re-admissions for other unrelated pathologies such as hemorrhoidectomy or removal of ureteral catheter.

The following data were recorded: age, sex, ASA classification, biliary disease prior to the intervention, data related to the admission in which the cholecystectomy was performed, days from initial discharge to re-hospitalization, and reason for re-hospitalization, defined as surgical-biliary, surgical non-biliary and non-surgical following Rana et al[13]’s classification.

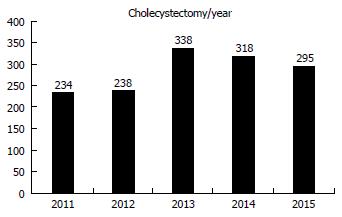

We retrospectively analyzed 1, 23 patients. The distribution by years is shown in Figure 1. Three-quarters (75.61%) of the cholecystectomies were performed electively and 24.39% as emergencies.

There were 71 readmissions in the 90 d after discharge (readmission rate 4.99%), 41 of them women and 30 men. The mean age at readmission was 68.9 ± 15.7 years. With regard to patients’ comorbidities, 14.08% were ASA I, 33.8% ASA II, 43.66% ASA III and the remaining 8.45% ASA IV.

Of the 71 readmissions, 64.79% occurred after elective surgery for cholelithiasis or vesicular polyps, and 35.21% after emergency surgery (for acute cholecystitis in 24 cases and for acute pancreatitis in one).

Of the electively operated patients, 76.09% underwent a laparoscopic approach, 13.04% right subcostal laparotomy and 10.87% required conversion to open surgery due to biliary tract injury, biliary tract scan, bleeding, or scleroatrophic gallbladder). In emergency surgeries, 92% (23/25) were performed by open surgery and two by laparoscopic approach, with no need for conversion.

Surgical non-biliary causes were the most frequent reasons for readmission, representing 46.48%; among them, intra-abdominal abscesses were the most common (approximately one in four). In second place were non-surgical reasons, at 29.58%, and finally, surgical biliary reasons, at 23.94%.

Of the 71 patients, seven required a second readmission within 90 d of the initial discharge. In four cases the reason for the second readmission was related to the first one (cholangitis, choledocholithiasis and intra-abdominal abscess). In the other three, the second readmissions were due to non-surgical causes of respiratory origin.

There were two deaths during readmission: an elderly patient with septic shock of undiagnosed cause who died a few hours after arriving in the emergency room, and another patient readmitted for aspiration pneumonia.

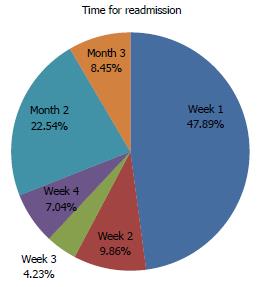

Figure 2 shows the distribution in time for readmissions in our series. The median time from discharge to readmission was 8 d (range: 1-88). Almost 50% of patients were readmitted in the first week after discharge, and most second readmissions occurred during the second month.

Seven out of 10 readmissions occurred in the first month after discharge, and the other three between 30 and 90 d. Redefining the readmission rate to 90 d resulted in an increase in re-hospitalization, from 3.51% at 30 d to 4.99% at 90 d.

In the 21 patients readmitted between 30 and 90 d after discharge, the reason was non-surgical in nine, surgical biliary in eight and surgical non-biliary in four. Table 1 shows the reasons for readmission at 30 and 90 d.

| 30 d-readmission: 50 patients | 90 d-readmission: 71 patients |

| Biliary: 18.00% | Biliary: 23.94% |

| Acute pancreatitis: 2 | Acute pancreatitis: 5 |

| Choledocholitiasis: 5 | Choledocolitiasis: 8 |

| Cholangitis: 0 | Cholangitis: 2 |

| Bile leak: 2 | Bile leak: 2 |

| Surgical-nonbiliary: 50.00% | Surgical-nonbiliary: 46.48% |

| Site-surgical infection: 3 | Site-surgical infection: 3 |

| Intraabdominal abscess: 16 | Intraabdominal abscess: 18 |

| Intraabdominal haematoma: 4 | Intraabdominal haematoma: 4 |

| Abdominal wall hernias: 0 | Abdominal wall hernias: 2 |

| Abdominal pain: 1 | Abdominal pain: 5 |

| Others: 1 | Others: 1 |

| Non-surgical: 32.00% | Non-surgical: 29.58% |

| Pulmonary: 6 | Pulmonary: 11 |

| Gastrointestinal: 4 | Gatrointestinal: 5 |

| Central nervous system: 1 | Central nervous system: 2 |

| Cardiac: 1 | Cardiac: 1 |

| Renal: 1 | Renal: 1 |

| Others: 3 | Others: 1 |

Data on age, ASA, reason for cholecystectomy and median time for readmission (in days) are shown both overall and comparatively in the sub-groups divided according to reason for readmission (intra-abdominal abscess, surgical-biliary and non-surgical) are shown in Table 2.

| Global | Intraabdominal abscess | Surgical-biliary | Non-surgical | |

| Readmissions | 71 | 18 (25.35%) | 17 (23.94%) | 21 (29.58%) |

| Age (yr ± DS) | 68.9 ± 15.7 | 69.42 ± 14.6 | 65.58 ± 17.5 | 73.48 ±16.6 |

| ASA | ||||

| ASA I | 10 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| ASA II | 24 | 6 | 8 | 5 |

| ASA III | 31 | 9 | 5 | 10 |

| ASA IV | 6 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Reason for cholecystectomy | ||||

| Cholelithiasis | 44 | 14 | 10 | 9 |

| Cholecystitis | 22 | 2 | 6 | 11 |

| Polyps | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Others | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Time for readmission (median, range) | 8 (1-88) | 6.5 (1-42) | 29.5 (2-81) | 10 (1-88) |

| More than 30 d | 29.58% (21/71) | 11.11% (2/18) | 47.06% (8/17) | 33.33% (7/21) |

Due to the high prevalence of biliary pathology, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is one of the most frequent surgical procedures.

In one of the few articles published in the literature, Rana et al[13] analyzed re-hospitalizations at 30 d after laparoscopic procedures and found an overall readmission rate of 5.9%. Surgical reasons (54.4%) were the most frequent cause, and 50% of re-hospitalizations occurred in the first week. These figures are slightly higher than the ones obtained in our series, which also includes open surgery and conversions (3.51% at 30 d and 4.99% at 90 d). Studying readmissions at 90 d after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Down et al[14] observed a rate closer to ours (4.3%); however, those authors analyzed only laparoscopic procedures and excluded causes of readmission such as urinary tract infection, thoracic pain or gastritis, which we included in our series under the heading of non-surgical reasons. An analysis with a mean follow-up of four years after elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy[4] found an overall rate of readmissions of 6.6%, with the highest proportion being recorded during the first six weeks after discharge; however, in that study patients with cholecystitis of more than 48 h of evolution were excluded.

In order to be able to compare results, then, it is essential to standardize criteria regarding the reasons for readmission. In our opinion, scheduled readmissions due to another unrelated pathology, malignancy in the resection specimen or active oncologic disease should not be included.

Rana et al[13] reported the following rates for readmission according to cause: surgical-biliary in 22.7% of cases, surgical non-biliary in 31.8%, and non-surgical in 45.4%. In our series, following the same classification, 23.94% of readmissions were for surgical-biliary reasons, 46.48% for surgical non-biliary reasons, and 29.58% for non-surgical reasons. In our series, surgical-non-biliary causes predominated due to the presence of intra-abdominal abscesses, and there was a lower rate of readmissions for non-surgical reasons.

In all likelihood, many of the medical reasons for readmission included in our study are not related to the surgical procedure. We wanted to ensure that our recording of complications was comprehensive, since there is currently no consensus regarding which medical reasons for readmission should be included in this type of study.

Multiple factors have been associated with readmission after surgery[6,15]: age, race, associated comorbidities, preoperative hospital stay over seven days, and ICU stay. In the specific case of cholecystectomy, emergency surgery, the duration of symptoms and the surgeon’s experience are additional factors to be considered[1]. Intraoperatively, the concept of “difficult cholecystectomy” has been described[16], which may be related to a higher rate of postoperative complications. Some previous studies[17,18] have sought to establish preoperative and intraoperative classifications to predict the risks of complications associated with the procedure, and can help us to standardize our criteria in this regard.

In our series, the high rate of intra-abdominal abscesses could be explained by the intraoperative findings of “difficult cholecystectomy”; we need to standardize our criteria in this regard. Alternatively, the presence of these abscesses may be due to the chronic cholecystitis identified by histology study of all the specimens analyzed.

The use of a 30 d cutoff point to determine the rate of readmissions may in fact underestimate the true incidence of complications and associated costs. An article published in 2011 on the results after liver surgery[19] found that extending the period for measuring mortality to 90 d increased the rate reported by 50%, and since then the trend has been to measure complications and readmissions 90 d after hospital discharge. In our series, the use of the 90 d cutoff point increased the readmission rate from 3.51% at 30 d to 4.99% at 90 d. This finding mainly reflects readmissions for biliary pathology, in which eight of the 17 re-hospitalizations reported at our service occurred between 30 and 90 d post-surgery.

Currently most studies of complications after major surgery use 90 d as a time limit. Cholecystectomy is a common procedure with a low complication rate, but we think that the use of a 90-d limit is necessary to standardize criteria in morbidity studies. At present few studies of cholecystectomy use this criterion.

The aim of our study was to determine the rate of readmissions after cholecystectomy and to identify the reasons for re-hospitalization. Prospective studies are now needed to analyze the risk factors that increase this rate. It is also important to assess the impact of readmission on overall cost. At present, there are no consensus criteria for defining preventability; the retrospective nature of our study does not allow us to give a uniform definition of this concept, and prospective studies are needed to be able to do so reliably

In conclusion, the rate of readmissions following a surgical procedure is an important indicator of the quality of care. This paper is one of the first to analyze readmissions after elective or emergency cholecystectomy (both laparoscopic and open) at 90 d. Prospective studies recording intraoperative findings are now needed in order to identify factors that may predict readmissions.

The target of this study is to determine the incidence of readmission after cholecystectomy, one of the most frequently performed surgical procedures in a General Surgery Department. It can be an indicator of the quality of care and also it can be related with important socioeconomic costs.

The use of a 30-d cutoff point to determine the rate of readmissions may underestimate the true incidence of complications, the authors wanted to extend our limit to 90 d following the tendency initiated by an article published in 2011 on mortality after hepatectomy where the cutoff point was stablish in 90 d.

This article is the first one that considers 90 d as the cutoff point for readmissions after cholecystectomy. Authors have included all readmission without excluding any medical causes in order to avoid underestimation related to cholecystectomy. They also have included all cholecystectomies, laparotomic and laparoscopic and also elective and urgent procures.

The presented article can provide data to analyze the readmissions and their causes and from there on to create prospective studies to know the risk factors and the preventable causes, thus being able to find measures to improve and reduce readmissions and their socioeconomic costs.

It is an interesting study to use 90-d as a time limit to determine the incidence of readmission after cholecystectomy. However, the more comparasion of 30-d to 90-d readmission is lack, such as different complication or risk factors. It is better to explain the difference between them in more details. Anyway, the study is nice.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chuang SH, Ding WJ, Koller T S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Boehme J, McKinley S, Michael Brunt L, Hunter TD, Jones DB, Scott DJ, Schwaitzberg SD. Patient comorbidities increase postoperative resource utilization after laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2217-2230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fry DE, Pine M, Nedza S, Locke D, Reband A, Pine G. Hospital Outcomes in Inpatient Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy in Medicare Patients. Ann Surg. 2016; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tsui C, Klein R, Garabrant M. Minimally invasive surgery: national trends in adoption and future directions for hospital strategy. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2253-2257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sanjay P, Weerakoon R, Shaikh IA, Bird T, Paily A, Yalamarthi S. A 5-year analysis of readmissions following elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy - cohort study. Int J Surg. 2011;9:52-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Department of Health. NHS reference costs. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH062884;2005e06. |

| 6. | Havens JM, Olufajo OA, Cooper ZR, Haider AH, Shah AA, Salim A. Defining Rates and Risk Factors for Readmissions Following Emergency General Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:330-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kocher RP, Adashi EY. Hospital readmissions and the Affordable Care Act: paying for coordinated quality care. JAMA. 2011;306:1794-1795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Joynt KE, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmissions--truth and consequences. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1366-1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 343] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3684] [Cited by in RCA: 3914] [Article Influence: 244.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, Bueno H, Ross JS, Horwitz LI, Barreto-Filho JA, Kim N, Bernheim SM, Suter LG. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309:355-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 703] [Cited by in RCA: 778] [Article Influence: 64.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fry DE, Pine M, Pine G. Ninety-day postdischarge outcomes of inpatient elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgery. 2014;156:931-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Halawani HM, Tamim H, Khalifeh F, Mailhac A, Jamali FR. Impact of intraoperative cholangiography on postoperative morbidity and readmission: analysis of the NSQIP database. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:5395-5403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rana G, Bhullar JS, Subhas G, Kolachalam RB, Mittal VK. Thirty-day readmissions after inpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy: factors and outcomes. Am J Surg. 2016;211:626-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Down SK, Nicolic M, Abdulkarim H, Skelton N, Harris AH, Koak Y. Low ninety-day re-admission rates after emergency and elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a district general hospital. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92:307-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | McIntyre LK, Arbabi S, Robinson EF, Maier RV. Analysis of Risk Factors for Patient Readmission 30 Days Following Discharge From General Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:855-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sinha R. Difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy -when and where is the need to convert? Apollo Medicina. 2010;7; 135-137. |

| 17. | Sugrue M, Sahebally SM, Ansaloni L, Zielinski MD. Grading operative findings at laparoscopic cholecystectomy- a new scoring system. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bourgouin S, Mancini J, Monchal T, Calvary R, Bordes J, Balandraud P. How to predict difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Proposal for a simple preoperative scoring system. Am J Surg. 2016;212:873-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mayo SC, Shore AD, Nathan H, Edil BH, Hirose K, Anders RA, Wolfgang CL, Schulick RD, Choti MA, Pawlik TM. Refining the definition of perioperative mortality following hepatectomy using death within 90 days as the standard criterion. HPB (Oxford). 2011;13:473-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |