Published online Apr 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i15.2660

Peer-review started: January 4, 2017

First decision: February 10, 2017

Revised: February 27, 2017

Accepted: March 21, 2017

Article in press: March 21, 2017

Published online: April 21, 2017

Processing time: 109 Days and 16.3 Hours

The development of pancreatic fluid collections (PFC) is one of the most common complications of acute severe pancreatitis. Most of the acute pancreatic fluid collections resolve and do not require endoscopic drainage. However, a substantial proportion of acute necrotic collections get walled off and may require drainage. Endoscopic drainage of PFC is now the preferred mode of drainage due to reduced morbidity and mortality as compared to surgical or percutaneous drainage. With the introduction of new metal stents, the efficiency of endoscopic drainage has improved and the task of direct endoscopic necrosectomy has become easier. The requirement of re-intervention is less with new metal stents as compared to plastic stents. However, endoscopic drainage is not free of adverse events. Severe complications including bleeding, perforation, sepsis and embolism have been described with endoscopic approach to PFC. Therefore, the endoscopic management of PFC is a multidisciplinary affair and involves interventional radiologists as well as GI surgeons to deal with unplanned adverse events and failures. In this review we discuss the recent advances and controversies in the endoscopic management of PFC.

Core tip: The management of pancreatic fluid collections has revolutionised over last several decades. New devices and techniques have evolved which have largely obviated the need for surgery in these patients. The differentiation of nature of fluid collections into pseudocyst and walled off necrosis has enabled the endoscopist to plan management strategies. With the introduction of dedicated metal stents, the task of endoscopic necrosectomy has become easier. However, all patients with pancreatic fluid collections cannot be managed in the same way. Therefore, the management of pancreatic fluid collections (PFC) requires multidisciplinary and individualised approach. In this review, we describe the recent advances and controversial issues in the endoscopic management of PFC.

- Citation: Nabi Z, Basha J, Reddy DN. Endoscopic management of pancreatic fluid collections-revisited. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(15): 2660-2672

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i15/2660.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i15.2660

Acute pancreatitis is an acute inflammatory process involving pancreas, characterized by upper abdominal pain and more than three-fold rise in pancreatic enzymes[1,2]. The development of pancreatic fluid collections (PFCs) is a common complication of severe acute pancreatitis. The revised Atlanta classification categorizes PFC into four sub-types- acute pancreatic fluid collections (APFC), acute necrotic collections (ANC), pseudocysts and walled off necrosis (WON)[3]. The differentiation of these collections is mainly based on the duration (< or > 4 wk) and nature of collections (necrotic or non-necrotic). APFC (≤ 4 wk) develop after an episode of interstitial edematous pancreatitis (IEP) and may evolve into pseudocyst after 4 wk. Whereas, ANC (≤ 4 wk) develop after acute necrotizing pancreatitis and subsequently transform into WON after 4 wk. By definition, pseudocysts have clear contents and WON have variable amount of solid necrotic debris[3]. The present classification of fluid collections and severity of acute pancreatitis has important implications on the management as well as clinical outcomes in these patients[4-7].

Acute collections (APFC or ANC) usually do not require any intervention for drainage as most improve with conservative management. However, a substantial proportion of symptomatic WON and pseudocysts require some drainage intervention. With the development of technical innovations in interventional endoscopy, invasive surgical procedures can be avoided in majority of these patients. New techniques and devices have emerged to improve the efficacy and safety of endoscopic drainage of PFCs. In this review we shall highlight the recent advances and controversies in the endoscopic management of PFCs.

The clinical outcome and requirement of an intervention in patients with PFCs is largely determined by the knowledge of their behavior with due course of time. The evolution and behavior of APFC and ANC may be different. A prospective multicenter study analyzed the clinical course of PFCs in acute pancreatitis. Out of 302 patients with acute pancreatitis, 129 patients (42.7%) had APFC. Majority (70%) of these APFC resolved spontaneously, while about 15% developed pseudocysts. On subsequent follow-up about a quarter of pseudocysts disappeared completely[1]. The nature of PFC (pseudocyst or walled off necrosis) and its influence on the natural history were not depicted in this study. In a prospective cohort study including majority of patients with ANP, about half of the ANC transformed into WON. In more than 50% cases, WON resolved spontaneously without requirement of an intervention. Therefore, in about 3/4th cases ANC resolved before or after evolving into WON[8]. In a more recent study including 189 patients, 153 patients (81%) were classified as ANP and 36 (19%) with interstitial oedematous pancreatitis (IEP). About 22% patients with IEP developed APFC of which only one patient subsequently advanced to pseudocyst. In contrast, majority of patients with ANP developed ANC. Of these, about 55% patients developed WON of which 63% required an intervention[9].

It can be concluded that majority of APFC resolve spontaneously and only a minority transform into pseudocyst, whereas a sizeable proportion of ANC transform into WON.

Over the last few decades, few critical observations have been made regarding the management of PFCs. First, the outcome of any drainage intervention is better if an intervention is performed after the collection gets walled off (> 4 wk) or encapsulated. Second, minimally invasive management of PFCs is better than the conventional surgical approach[10-13]. Third, the outcomes of endoscopic drainage depend on the nature of PFCs, i.e., pseudocyst or WON[14].

The foundation of minimally invasive management of PFCs (especially WON) was laid by two landmark studies. The first study concluded that step-up surgical approach (i.e., per-cutaneous drainage followed by minimally invasive retroperitoneal necrosectomy) resulted in less major complications and mortality as compared to the open necrosectomy group[11]. In the second study, endoscopic necrosectomy reduced the pro-inflammatory response as well as new onset organ failure as compared to surgical necrosectomy in patients with infected necrotizing pancreatitis[10].

The concept of step-up approach has now gained world-wide acceptance. Initial management of symptomatic PFCs constitutes antibiotics and nutritional support, followed by minimally invasive drainage (endoscopic, percutaneous or surgical) if symptoms persist. Necrosectomy (endoscopic or surgical) should be considered only if there is no response to these measures.

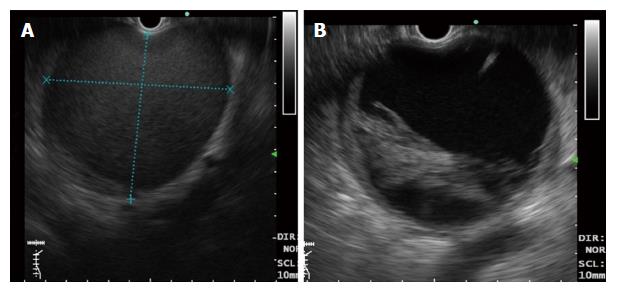

Endoscopic transmural drainage (ETD) has been used effectively for over two decades’ now. However, certain drawbacks are noteworthy with ETD. First, it requires an endoluminal bulge for it to be successfully performed. However, some PFCs like those located in the tail of pancreas usually do not produce a luminal compression. Second concern is the risk of bleeding due to presence of intervening vessels or collaterals which may not be taken care of in ETD. Endoscopic ultrasound guided transmural drainage (EUS-TD) enables the drainage of non-bulging PFCs, provided they are at a reasonable distance (< 1.5 cm) from the gastric wall[15]. In a RCT, the technical success with EUS-TD was significantly higher than conventional-ETD even after adjusting for luminal compression. There were two bleeding episodes in the conventional group vs none in EUS-TD group[16]. EUS-TD, therefore is not only more effective but also appears to be safer as it allows the visualization of any intervening vessels. In addition, the amount of necrotic debris can be assessed for deciding appropriate management strategies. While, Contrast CT is often utilized as the initial imaging modality in these patients, it is suboptimal in picturing debris inside the cyst cavity. EUS and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are superior for qualitative as well as quantitative assessment of contents of PFCs[17-19].

At this juncture, it can be concluded that when available EUS-TD is preferable for drainage of PFCs[20].

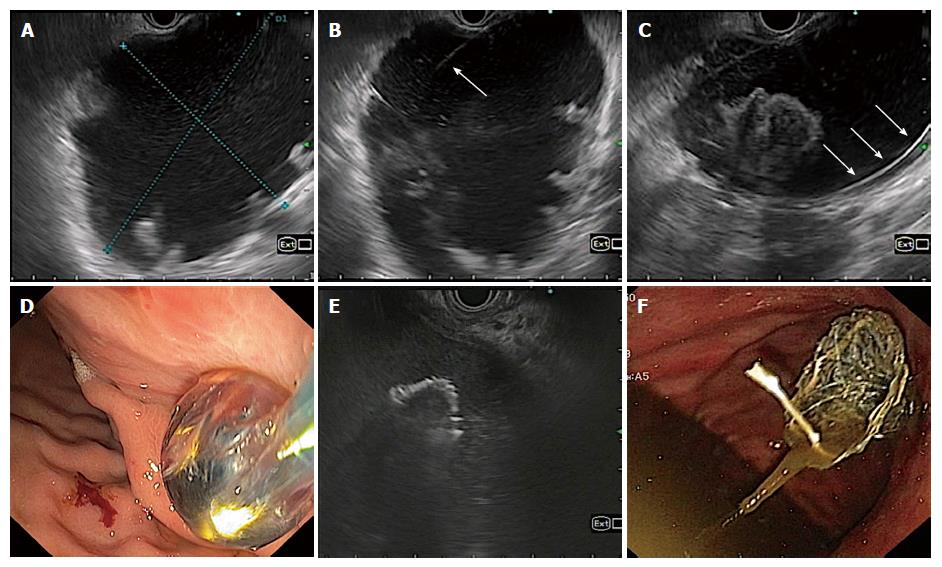

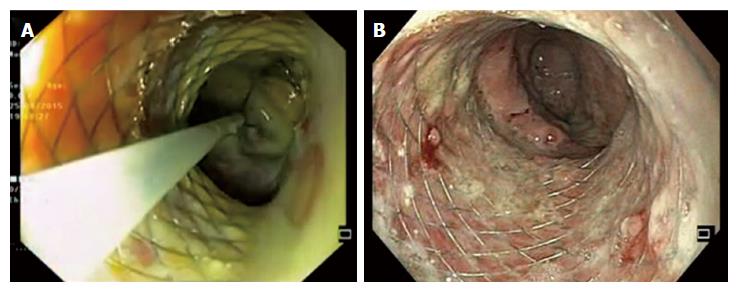

Endoscopic drainage of PFCs is accomplished by placing cysto-gastric stents (plastic or metal). The technique involves standard sequence of steps as follows - identification of ideal puncture site under EUS guidance, needle puncture of PFC wall, coiling of guidewire inside the cyst cavity, dilatation of cysto-gastric tract (cystotome and balloon) and finally placement of stents (Figure 1). The identification of the nature of PFCs is crucial in determining the outcome of endoscopic drainage. WON have variable amount of necrotic debris as compared to pseudocysts which may preclude complete drainage (Figure 2). Therefore, the success rate of endoscopic drainage is relatively lower and requirement of repeated endoscopic interventions is frequent as compared to pseudocysts[14]. Additional measures like placement of a naso-cystic tube for irrigation and direct endoscopic necrosectomy (DEN) have been utilized to improve the success rates. Despite of all the efforts, the overall success rate of endoscopic drainage is lower in WON (63%-81%) as compared to that in pseudocysts (86%-100%)[17].

EUS-TD was initially described in early 1990’s. Since then numerous studies have been published revealing excellent outcomes of endoscopic drainage of pseudocysts. Endoscopic drainage of pseudocysts is successful in about 86%-100% of cases[17]. The advantages of EUS-TD over ETD have been described earlier in this review. Endoscopic drainage of pseudocysts is accomplished by placing one or more pigtail plastic stents (7 or 10 Fr). The size and number of plastic stents probably do not play a role in the successful outcome of endoscopic drainage of pseudocysts. In a recent retrospective study, there was no relation between the treatment outcome and stent characteristics (number and size - 7 or 10 Fr) in patients undergoing endoscopic drainage of uncomplicated pancreatic pseudocysts[21]. However, the results may not apply to WON or complex pseudocysts where larger stents or multiple stents may prove to be beneficial.

Several studies have compared the outcomes of endoscopic drainage with surgical cysto-gastrostomy and percutaneous drainage[13,22-24], The only RCT conducted by Varadarajulu et al[13] concluded that both the modalities are equally effective with shorter hospital stay and lower costs in the endoscopic group. However, surgical drainage was performed by open procedure rather than laparoscopic cysto-gastrostomy. In another study, laparoscopic cysto-gastrostomy outperformed endoscopic drainage. But, the clinical success was unusually low in the endoscopic group (51.1%) in this study, in contrast to most of the published literature (86%-100%)[17]. Therefore, more RCTs are required to determine the superiority of one approach over the other.

The literature comparing endoscopic and percutaneous drainage is limited. In one retrospective study, both the modalities were found to have equal efficacy. However, percutaneous drainage group had higher rates of re-intervention and longer length of hospital stay[24]. The development of troublesome external pancreatic fistula and infection are major drawbacks associated with percutaneous drainage. External pancreatic fistula is the most common complication and develops in about 8.2% patients undergoing percutaneous drainage for infected pancreatic necrosis[25]. A recent systematic review compared endoscopic, percutaneous and surgical pancreatic pseudocyst drainage. The authors concluded that both endoscopic and surgical drainage are equally effective, with shorter hospital stay, less cost and better quality of life in the endoscopic group. Nevertheless, surgical or percutaneous drainage may be considered in patients with disapproving anatomy[26].

The standard endoscopic drainage technique has yielded satisfactory clinical outcomes in pseudocysts. However, the same has been sub-optimal for efficiently draining WON. Therefore, a complementary procedure is frequently required to improve the results in patients with WON. The innovations in devices and techniques in this regard include - use of naso-cystic catheter (NCT) for irrigation, multiple transluminal gateway technique, DEN, development of novel metal stents, dual modality drainage and the endoscopic step up approach[27-35].

The placement of NCT allows irrigation of the cyst cavity with saline or hydrogen peroxide and facilitates the drainage of viscous contents in WON. In a retrospective study, the clinical success was significantly higher and stent occlusion lower in the combination group (NCT + plastic stents) when compared to plastic stent only group[35].

In the multiple transluminal gateway technique technique, 2 or 3 transmural tracts are fashioned between the necrotic cavity and the GI tract. One of the tracts is used for irrigation via a NCT and multiple plastic stents are arrayed in other tracts to assist drainage of necrotic debris[27]. Multiple tracts enable rapid and efficient drainage in cases of large WON[36].

The “bigger” the “better” theory has been optimally utilised at various luminal territories in GI tract. The motive behind the use of metal stents is to overcome the problem of sub-optimal drainage efficiency of plastic stents in WON[37]. Metal stents have larger diameter and permit for endoscopic necrosectomy. In the initial small studies, covered biliary metal stents and to a lesser extent esophageal stents were used for trans-enteric drainage[38-42]. Although these stents provided efficient drainage, few inherent limitations precluded their widespread use. Biliary metal stents have anti-migration features (like anti-migratory fins) which are not suitable for cysto-enteric drainage. Therefore, pigtail plastic stents were used to anchor these stents across the cysto-gastric tract to prevent migration[40]. These stents are long with relatively small lumen which increases the chances of erosions or ulceration over gastric or retroperitoneal side and hindrance for DEN[43]. Nevertheless, it would be unfair to criticize biliary stents, as they were designed for biliary drainage rather than drainage of PFCs.

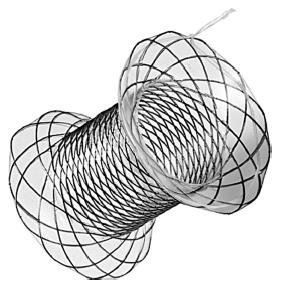

The unmet gap of a dedicated metal stent for trans-enteric drainage has largely been filled with the availability of novel metal stents. These stents have been specially designed for the drainage of PFCs and have either lumen apposing property like Axios stent (Xlumena, Mountain View, CA, United States), Niti-S SPAXUS stent (TaeWoong Medical Co., Ltd., Ilsan, South Korea) or are bi-flanged like Nagi stent (Taewoong Medical Co, Ilsan, South Korea), Aixstent (Leufen Medical, Aachen, Germany) and the Hanarostent BCF (M.I. Tech. Co., Inc., Seoul, South Korea) to offset migration rates especially during debridement (Figure 3)[44]. The stents are fully covered with silicone membrane to minimize tissue ingrowth and difficulty in removal. The efficacy and safety of these dedicated metal stents has been proven unequivocally in multiple recent studies[33,34,43,45-50] (Table 1).

| Study | n | Stent used | Size (cm) | Technical success, % | Clinical success, % | Necrosectomy, % |

| Walter et al[49], 2015 | 61 | AXIOS | 9.0 | 98.0 | PC-93 | 43.0 |

| PC-15 | WON-81 | |||||

| WON-46 | ||||||

| Shah et al[48], 2015 | 33 | AXIOS | 9 ± 3.3 | 91.0 | 93.0 | 33.0 |

| Chandran et al[46], 2015 | 47 | NAGI | 10.0 | 98.0 | 19.2 | |

| PC-38 | 76.6 | |||||

| WON-9 | ||||||

| Siddiqui et al[34], 2016 | 82 | AXIOS | 11.8 | 97.5 | PC-100 | All WON |

| PC-12 | WON-88 | |||||

| WON-68 | ||||||

| Sharaiha et al[54], 2016 | 124 | AXIOS | 9.5 | 100.0 | 86.3 | 62.9 |

| All WON | ||||||

| Rinninella et al[45], 2015 | 93 | Hot AXIOS | 10.0 | 98.9 | PC-100 | 59.6 |

| PC-18 | WON-90.4 | |||||

| WON-52 | ||||||

| Lakhtakia et al[65], 2016 | WON-205 | NAGI | 10.8 | 99.0 | 96.5 | 9.2 |

| Vazquez-Sequeiros et al[50], 2016 | 211 | FCMS-139 | 9.3 | 97.0 | 94.0 | 17.0 |

| PC-112 | AXIOS-72 | |||||

| WON-99 |

Newly designed metal stents are easy to deploy with technical success of > 90% in recent studies. In a retrospective case-control study, the median procedural duration was significantly shorter for lumen apposing metal stents (LAMS) as compared to plastic stents (8.5 vs 25 min, P < 0.001)[51]. Procedural duration is proportional to the difficulty of technique and matters the most in sick patients.

Clinical success is impressive with new metal stents ranging from 76%-100%. The common adverse events (AE) include- bleeding (1%-7%), perforation (1%-2%), stent migration (1%-6%) and infection (1%-11%). In a multicentre study, Siddiqui et al[34] found metal stents could be successfully placed in 97.5% patients. PFC resolution was achieved in all cases (100%) with pseudocyst and 88.2% of cases with WON. There was no incidence of endoscopic debridement related stent migration. In a large Spanish study including 211 patients with PFCs (pseudocyst-53%, WON-47%), straight biliary metal stents and new LAMS were utilized. Both stents fared equally with respect to clinical success and adverse events. The overall rate of adverse events was 21%, including infection, bleeding, stent migration and perforation[50]. Another study comparing fully covered self expanding metal stent (FCSEMS) with LAMS, reported that although clinical outcomes were similar in both the groups, significantly fewer interventions were required in LAMS group[52].

Large comparative studies between metal and plastic stents are lacking. Limited data suggests that in WON metal stents are more efficacious, easier to deploy with shorter procedural duration and associated with lower AE in patients with WON (Table 2)[52-55]. Siddiqui et al[52] retrospectively compared plastic stents with FCSEMS and LAMS in patients with WON. Metal stents (FCSEMS or LAMS) fared better in terms of clinical success and AE. LAMS was better than FCSEMS with respect to the number of procedures required for resolution of WON. In another retrospective study comparing plastic stents with metal stents (covered biliary stents) for pancreatic pseudocysts, procedure related adverse events were significantly higher in the plastic stent group[54]. In contrast, few studies conclude otherwise with no difference in clinical outcomes between metal and plastic stents. Bang et al[51] compared plastic stents with LAMS retrospectively. The clinical outcomes were similar in both the groups, but costs significantly higher in the LAMS group. In the only randomized study (50 patients), Lee et al[55] concluded that both FCSEMS and plastic stents have equal efficacy for PFCs. However, metal stents were easier to deploy with shorter procedure time than plastic stents. In a systematic review, the pooled success rates and AE for endoscopic drainage of pseudocysts and WON were comparable using plastic or metal stents. However, newly designed metal stents (Axios in two studies, Nagi in one study) were used in only three studies in this review[56]. Moreover, the studies using metal stents included small number of patients. More recent studies display excellent outcomes with less technical difficulty or procedure duration while using novel metal stents in PFCs[53,55]. This is especially important in sick patients and when there is high likelihood of re-intervention for debridement or necrosectomy. Large randomized trials are required to prove the efficacy of metal stents over plastic stents for WON.

| Study | PFC type | n | Success | AE | Conclusion |

| Lee et al[55] 2014 | WON-14 | PS-25 | 90.9% | 8% | Efficacy equal |

| PC-36 | FCMS-25 | 87% | 0 | Re-intervention: FCMS = PS | |

| AE: FCMS = PS | |||||

| Mukai et al[53] 2015 | WON | PS-27 | 92.6% | 18.5% | Efficacy and AE: BFMS = PS |

| BFMS-43 | 97.7% | 7% | Re-intervention: BFMS < PS | ||

| AE: BFMS = PS | |||||

| Sharaiha et al[54] 2015 | PC | PS-118 | 89% | 31% | Efficacy: FCMS > PS |

| FCMS-112 | 98% | 16% | AE: FCMS < PS | ||

| Siddiqui et al[52] 2016 | WON | PS-106 | 81% | 7.5% | Efficacy: FCMS, LAMS > PS |

| FCMS-121 | 95% | 1.6% | Re-intervention: LAM < FCMS < PS | ||

| LAMS-86 | 90% | 9.3% | AE: LAMS = PS > FCMS | ||

| Bapaye et al[76] 2016 | WON | PS-61 | 73.7% | 36.1% | Efficacy: BFMS > PS |

| BFMS-72 | 94% | 5.6% | Re-intervention: BFMS < PS | ||

| AE: BFMS < PS |

One distinct advantage of plastic over metal stents is that they can be left in situ for prolonged duration in cases of non-resolving PFCs or disconnected pancreatic duct (PD)[57,58]. Metal stents need to be removed after a finite duration as stent impaction due to tissue ingrowth or overgrowth is a possibility[46].

Open necrosectomy is associated with high mortality and morbidity and therefore, has largely been replaced by minimally invasive necrosectomy[59]. Minimally invasive retroperitoneal necrosectomy has been shown to be superior as compared to surgical necrosectomy in a randomized study[11]. In the present era, endoscopic necrosectomy is preferred over open or minimally invasive surgical necrosectomy. A number of studies have established the safety and efficacy of DEN[60-62]. Endoscopic necrosectomy is associated with reduced formation of pancreatic fistula as compared to surgical drainage[10]. DEN is probably more efficacious (81% vs 61%) with less mortality (6% vs 13%) and reduced occurrence of pancreatic fistulae (5% vs 17%) than minimally invasive surgery (VARD)[63].

The technique of DEN involves dilatation of the cysto-gastric tract with a balloon, followed by advancement of the endoscope into the cavity of WON (Figure 4). Subsequently, the cavity is lavaged with normal saline and necrotic debris are removed under direct vision using snares or baskets. Hydrogen peroxide can be used with the advantage of loosening up of necrotic tissue to facilitate its easy removal in between the sessions of DEN. Several sessions may be required for completing the DEN procedure. Unfortunately, there is no dedicated device designed for endoscopic necrosectomy and retrieval of necrotic material. Snares, forceps or baskets are used to remove the necrotic tissue, but appear to be suboptimal.

The clinical success of DEN in multicentre studies ranges from 75%-91%[60-62]. Overall complication rates range from 14%-33% with mortality in up to 11% patients. The most common complication of DEN is bleeding followed by perforation and infection[60-62]. Air embolism has also been described with DEN, therefore it is imperative to use CO2 for insufflation during the complete procedure[63].

With the development of novel metal stents, the task of DEN has become relatively easy. These stents have wide lumen and allow multiple sessions of DEN without the need of repeated dilatations of cysto-gastric tract.

DEN may be associated with significant complications and therefore should not be performed unless indicated. A conservative approach is reasonably efficacious to begin with. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis supports the concept of initial conservative approach for the management of infected pancreatic necrosis. About 2/3rd patients (64%) with infected pancreatic necrosis could be managed with conservative approach alone (percutaneous drainage)[64]. In case an endoscopic drainage is required, DEN can be avoided in majority of cases with a step up approach[65]. In a large single center study including 205 patients, bi-flanged metal stents were used and a step up approach utilized for the management of WON. In about 75% patients, clinical success was achieved by placing bi-flanged SEMS alone without any additional intervention. The next steps included de-clogging of SEMS followed by placement of NCT and finally DEN. With this approach DEN was required only in 9.2% cases to achieve an overall success rate of 96.5%[65].

Transpapillary drainage (TPD) of PFCs involves placement of pancreatic ductal stent, in cases with small collections (< 6 cm) communicating with the pancreatic duct[17]. Therefore, TPD is not beneficial if bridging of PD disruption is not achieved or the collection is large and non-communicating. In addition, there is risk of infecting the PFC with TPD. In the current era, TPD is usually not performed alone and often combined with transmural drainage (TMD) when indicated.

The occurrence of pancreatic ductal disruption is well known after acute severe pancreatitis[66,67]. It is logical to believe that the severity of pancreatitis or extent of necrosis would be proportional to the incidence of PD disruption. In a retrospective study, PD disruption was documented in 38% of patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis[68]. More patients in the extensive necrosis group had complete disruption as compared to those in the partial disruption group. The recurrence of PFCs was also high in complete disruption group[68]. Therefore it seems prudent that PD disruption should be addressed prior to the removal of cysto-gastric stents to prevent recurrence. PD stent may be placed at the time of index endoscopic drainage or before removing cysto-gastric stent. The current literature is divergent regarding the benefits of combined drainage over transmural drainage alone[47,66,67,69-71]. In a retrospective study including 110 patients, Trevino et al[67] concluded that combined drainage (TPD + TMD) has a positive impact on the resolution of PFCs. Interestingly, there was no difference in the recurrence rates of PFCs in trans-papillary stenting vs no stenting group. In a small prospective single center study, TPD in selected cases allowed early removal of FCSEMS and prevented the recurrence of PFCs. PD leak or disruption was an independent factor affecting PFC resolution at 3 wk[47]. In contrast to the above mentioned studies, the results of several studies failed to show any benefit of combined drainage over TMD alone[69,71]. In a retrospective study, there was higher albeit non-significant recurrence of PFCs in combined group as compared to TMD group alone. The authors proposed that placement of a trans-papillary stent hinders the maturation of cyst-enterostomy fistula[69]. However, the study population was heterogeneous and included patients with acute collections, necrotic collections, abscess and pseudocysts (acute and chronic). In a more recent multicenter study inclusive of a homogeneous study population (pancreatic pseudocysts), the authors concluded that there was no difference in the long-term radiological resolution of pseudocysts in combined (62%) vs trans-mural drainage group (69%). Moreover, on multivariate analysis - TPD was the only factor negatively associated with long-term radiological resolution of PFC[71].

The success rate of endoscopic bridging of complete PD disruption or disconnection is much lower than that of TPD in case of partial PD disruptions[66]. If disruption cannot be bridged the benefit is likely to be marginal if any. In a retrospective analysis, there was no additional benefit of TPD in complete PD disruptions (9/17, as compared to cyst-enterostomy or percutaneous drainage alone (52.9% vs 70.6%, P = 0.61)[70].

At this moment the role of TPD in the management of PFCs remains ambiguous. In cases of suspected disruption or disconnection it seems rational to bridge the gap with a plastic stent. Cysto-gastric plastic stents can be left in place in case PD leak cannot be bridged to reduce recurrences[57,58,72,73]. However, randomized trials are required to clear the prevailing dilemma.

Endoscopic drainage of PFCs is safe and major AE are uncommon. AE include - bleeding, perforation, infection and stent migration (Table 3). Rarely, air embolism and intestinal obstruction due to stent migration have also been reported after endoscopic drainage.

| Study | n | Perforation, % | Bleeding, % | Migration, % | Infection, % | Overall complications, % |

| Walter et al[49], 2014 | 61 | 1.6 | 6.5 | 4.9 | 6.5 | 9.0 |

| Chandran et al[46], 2015 | 54 | - | 5.5 | 20.4 | 4.0, 7.4 | Early-7.4 |

| Late-11.1 | ||||||

| Bapaye et al[43], 2015 | 19 | - | 5.3 | 5.3 | - | 10.5 |

| Rinninella et al[45], 2015 | 93 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 5.4 |

| Vazquez-Sequeiros et al[50], 2016 | 211 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 3.0 | 11.0 | 21.0 |

| Siddiqui et al[34], 2016 | 82 | 1.2 | 7.3 | - | 6.1 | 9.8 |

| Sharaiha et al[33], 2016 | 124 | - | Early-1.6 | Early-2.4 | Early-3.2 | Early-11.3 |

| Late-0 | Late-3.2 | Late-2.4 | Late-7.2 | |||

| Lakhtakia et al[65], 2016 | 205 | 1.0 | 2.9 | 2.4 | - | 3.9 |

The incidence of AE depends on several factors including - endoscopic vs EUS guided drainage, nature of collections (pseudocyst vs WON), DEN performed or not and type of stent used (plastic vs metal). Complications may be higher while draining WON as compared to pseudocysts. In a large retrospective study including 211 patients, complications were encountered in 17 patients (8.5%) and were higher for drainage of necrosis than pseudocyst or abscess (15.8% vs 5.2%, P = 0.02)[37]. Similarly DEN is associated with higher AE (see above). In few studies where endoscopic drainage was combined with DEN, up to one-fourth of patients suffered some complication[74,75].

In recent studies comparing plastic with metal stents - the AEs were either similar or lower in the metal stent group (Table 2)[52-55,76]. Metal stents can tamponade the edges of cysto-gastrostomy site, thereby reducing the occurrence of bleeding from puncture site. Larger size allows better drainage and less chances of occlusion and sepsis. In contrast, higher than expected delayed AE were encountered in the interim analysis of an ongoing RCT (plastic vs LAMS) in patients with WON. These AE included - delayed bleeding (3 patients, 3-5 wk), buried LAMS (2 patients, 5-6 wk) and biliary stricture (5 wk)[77]. Therefore, early removal of metal stents may be considered if the PFC has resolved.

The development of endoscopic drainage techniques has led to decline in the use of percutaneous and surgical drainage of PFCs. However, large WON and complex pseudocysts like those extending into paracolic gutters may be inadequately drained by endoscopic techniques alone. In addition, endoscopic drainage is not feasible if the PFC is situated at a distant location from the GI lumen. Therefore, in selected cases percutaneous drainage may complement the benefits of endoscopic drainage and help in circumventing the need of surgical necrosectomy. About 1/3rd to 2/3rd patients with WON improve with percutaneous drainage alone[11]. Dual modality drainage (endoscopic + percutaneous) appears safe and appealing and may reduce the chances of pancreatico-cutaneous fistula also[28,32]. In addition, other hybrid technique involves percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy with or without endoscopic drainage[78-80]. The data on safety and efficacy of these novel approaches is limited. Studies in future should clarify their role in difficult to manage PFCs.

The data for minimally invasive endoscopic management of PFCs is limited in children. The size of a standard adult EUS scope (about 14 mm) may be prohibitive for its use in small children (< 15 kg). Therefore, caution is advised while performing EUS-drainage in small children (< 15 kg)[81].

The available evidence (small case series) suggests that endoscopic drainage is safe and efficacious in paediatric age group[82-84]. More recently, the use of novel bi-flanged metal stent has been reported in children with WON[85,86]. Nabi et al[86] utilized bi-flanged metal stents in twenty-one children with WON. Technical success was achieved in all and clinical success documented in 95% of children. There were no major complications.

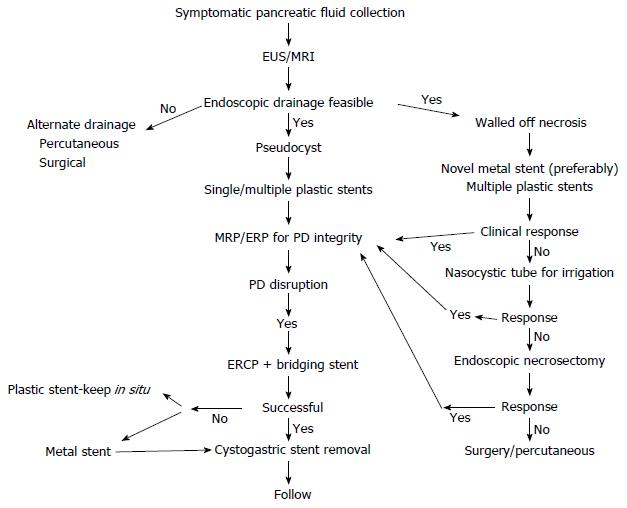

The management of PFCs needs to be tailored for each patient. The endoscopist should justify answers to several questions before attempting the drainage procedure. The first and foremost is the indication of drainage procedure. Asymptomatic collections need not be drained irrespective of their size. Second, is it the right time to drain. Acute collections usually resolve and endoscopic drainage is performed only under exceptional circumstances. Third, what would be the ideal route for draining the PFC in question. PFCs situated > 1.5 cm from the lumen are not usually amenable to endoscopic drainage and therefore alternate routes should be sought. Likewise, large collections extending into the paracolic gutters may require combined approach (endoscopic and percutaneous) for optimal results. Fourth, the nature of PFCs should be identified by suitable imaging (EUS or MRI). Characterisation of PFCs into pseudocyst and WON have critical therapeutic complications. WON have debris and therefore are more demanding than pseudocysts with clear contents. However, it should be acknowledged that sometimes the distinction between WON and pseudocyst is blurred. The decision to proceed is then dictated by the amount of debris in the cyst cavity. Lastly, appropriate endoprosthesis should be chosen for draining PFCs. The choice of stent is largely dependent on nature of PFCs and the possible need for re-interventions or DEN. Endoscopic drainage using one or more plastic stents seems to be good enough for pseudocysts. In contrast, WON should be drained with multiple plastic stents or newly available metal stents if multiple sessions of DEN are expected. Placement of a NCT in addition may be useful for irrigating the cavity. Subsequently, DEN should be performed only in cases with no improvement in symptoms (Figure 5).

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: India

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: García-Flórez LJ, Maluf-Filho F S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Cui ML, Kim KH, Kim HG, Han J, Kim H, Cho KB, Jung MK, Cho CM, Kim TN. Incidence, risk factors and clinical course of pancreatic fluid collections in acute pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:1055-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Singh P, Garg PK. Pathophysiological mechanisms in acute pancreatitis: Current understanding. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2016;35:153-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4340] [Article Influence: 361.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 4. | Acevedo-Piedra NG, Moya-Hoyo N, Rey-Riveiro M, Gil S, Sempere L, Martínez J, Lluís F, Sánchez-Payá J, de-Madaria E. Validation of the determinant-based classification and revision of the Atlanta classification systems for acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:311-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Talukdar R, Bhattacharrya A, Rao B, Sharma M, Nageshwar Reddy D. Clinical utility of the revised Atlanta classification of acute pancreatitis in a prospective cohort: have all loose ends been tied? Pancreatology. 2014;14:257-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nawaz H, Mounzer R, Yadav D, Yabes JG, Slivka A, Whitcomb DC, Papachristou GI. Revised Atlanta and determinant-based classification: application in a prospective cohort of acute pancreatitis patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1911-1917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bansal SS, Hodson J, Sutcliffe RS, Marudanayagam R, Muiesan P, Mirza DF, Isaac J, Roberts KJ. Performance of the revised Atlanta and determinant-based classifications for severity in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2016;103:427-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sarathi Patra P, Das K, Bhattacharyya A, Ray S, Hembram J, Sanyal S, Dhali GK. Natural resolution or intervention for fluid collections in acute severe pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1721-1728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Manrai M, Kochhar R, Gupta V, Yadav TD, Dhaka N, Kalra N, Sinha SK, Khandelwal N. Outcome of Acute Pancreatic and Peripancreatic Collections Occurring in Patients With Acute Pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2016; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bakker OJ, van Santvoort HC, van Brunschot S, Geskus RB, Besselink MG, Bollen TL, van Eijck CH, Fockens P, Hazebroek EJ, Nijmeijer RM. Endoscopic transgastric vs surgical necrosectomy for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1053-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 498] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, van Goor H, Schaapherder AF, van Eijck CH, Bollen TL. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1038] [Cited by in RCA: 1036] [Article Influence: 69.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Guenther L, Hardt PD, Collet P. Review of current therapy of pancreatic pseudocysts. Z Gastroenterol. 2015;53:125-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Varadarajulu S, Bang JY, Sutton BS, Trevino JM, Christein JD, Wilcox CM. Equal efficacy of endoscopic and surgical cystogastrostomy for pancreatic pseudocyst drainage in a randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:583-590.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Baron TH, Harewood GC, Morgan DE, Yates MR. Outcome differences after endoscopic drainage of pancreatic necrosis, acute pancreatic pseudocysts, and chronic pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:7-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Park DH, Lee SS, Moon SH, Choi SY, Jung SW, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided versus conventional transmural drainage for pancreatic pseudocysts: a prospective randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2009;41:842-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Varadarajulu S, Christein JD, Tamhane A, Drelichman ER, Wilcox CM. Prospective randomized trial comparing EUS and EGD for transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1102-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Holt BA, Varadarajulu S. The endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:804-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Foster BR, Jensen KK, Bakis G, Shaaban AM, Coakley FV. Revised Atlanta Classification for Acute Pancreatitis: A Pictorial Essay. Radiographics. 2016;36:675-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dhaka N, Samanta J, Kochhar S, Kalra N, Appasani S, Manrai M, Kochhar R. Pancreatic fluid collections: What is the ideal imaging technique? World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:13403-13410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Panamonta N, Ngamruengphong S, Kijsirichareanchai K, Nugent K, Rakvit A. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided versus conventional transmural techniques have comparable treatment outcomes in draining pancreatic pseudocysts. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:1355-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bang JY, Wilcox CM, Trevino JM, Ramesh J, Hasan M, Hawes RH, Varadarajulu S. Relationship between stent characteristics and treatment outcomes in endoscopic transmural drainage of uncomplicated pancreatic pseudocysts. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2877-2883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Varadarajulu S, Lopes TL, Wilcox CM, Drelichman ER, Kilgore ML, Christein JD. EUS versus surgical cyst-gastrostomy for management of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:649-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Melman L, Azar R, Beddow K, Brunt LM, Halpin VJ, Eagon JC, Frisella MM, Edmundowicz S, Jonnalagadda S, Matthews BD. Primary and overall success rates for clinical outcomes after laparoscopic, endoscopic, and open pancreatic cystgastrostomy for pancreatic pseudocysts. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:267-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Akshintala VS, Saxena P, Zaheer A, Rana U, Hutfless SM, Lennon AM, Canto MI, Kalloo AN, Khashab MA, Singh VK. A comparative evaluation of outcomes of endoscopic versus percutaneous drainage for symptomatic pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:921-928; quiz 983.e2, 983.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ke L, Li J, Hu P, Wang L, Chen H, Zhu Y. Percutaneous Catheter Drainage in Infected Pancreatitis Necrosis: a Systematic Review. Indian J Surg. 2016;78:221-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Teoh AY, Dhir V, Jin ZD, Kida M, Seo DW, Ho KY. Systematic review comparing endoscopic, percutaneous and surgical pancreatic pseudocyst drainage. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;8:310-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Varadarajulu S, Phadnis MA, Christein JD, Wilcox CM. Multiple transluminal gateway technique for EUS-guided drainage of symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:74-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ross AS, Irani S, Gan SI, Rocha F, Siegal J, Fotoohi M, Hauptmann E, Robinson D, Crane R, Kozarek R. Dual-modality drainage of infected and symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis: long-term clinical outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:929-935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ren YC, Chen SM, Cai XB, Li BW, Wan XJ. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided drainage combined with trans-duodenoscope cyclic irrigation technique for walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:38-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bang JY, Holt BA, Hawes RH, Hasan MK, Arnoletti JP, Christein JD, Wilcox CM, Varadarajulu S. Outcomes after implementing a tailored endoscopic step-up approach to walled-off necrosis in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1729-1738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bang JY, Varadarajulu S. Transmural drainage versus transpapillary stenting and transmural drainage: not an open and shut case yet. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Gluck M, Ross A, Irani S, Lin O, Gan SI, Fotoohi M, Hauptmann E, Crane R, Siegal J, Robinson DH. Dual modality drainage for symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis reduces length of hospitalization, radiological procedures, and number of endoscopies compared to standard percutaneous drainage. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:248-256; discussion 256-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Sharaiha RZ, Tyberg A, Khashab MA, Kumta NA, Karia K, Nieto J, Siddiqui UD, Waxman I, Joshi V, Benias PC. Endoscopic Therapy With Lumen-apposing Metal Stents Is Safe and Effective for Patients With Pancreatic Walled-off Necrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1797-1803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Siddiqui AA, Adler DG, Nieto J, Shah JN, Binmoeller KF, Kane S, Yan L, Laique SN, Kowalski T, Loren DE. EUS-guided drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections and necrosis by using a novel lumen-apposing stent: a large retrospective, multicenter U.S. experience (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:699-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Siddiqui AA, Dewitt JM, Strongin A, Singh H, Jordan S, Loren DE, Kowalski T, Eloubeidi MA. Outcomes of EUS-guided drainage of debris-containing pancreatic pseudocysts by using combined endoprosthesis and a nasocystic drain. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:589-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Bang JY, Wilcox CM, Trevino J, Ramesh J, Peter S, Hasan M, Hawes RH, Varadarajulu S. Factors impacting treatment outcomes in the endoscopic management of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1725-1732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Varadarajulu S, Bang JY, Phadnis MA, Christein JD, Wilcox CM. Endoscopic transmural drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections: outcomes and predictors of treatment success in 211 consecutive patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:2080-2088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Talreja JP, Shami VM, Ku J, Morris TD, Ellen K, Kahaleh M. Transenteric drainage of pancreatic-fluid collections with fully covered self-expanding metallic stents (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1199-1203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Weilert F, Binmoeller KF, Shah JN, Bhat YM, Kane S. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections with indeterminate adherence using temporary covered metal stents. Endoscopy. 2012;44:780-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Penn DE, Draganov PV, Wagh MS, Forsmark CE, Gupte AR, Chauhan SS. Prospective evaluation of the use of fully covered self-expanding metal stents for EUS-guided transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:679-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Attam R, Trikudanathan G, Arain M, Nemoto Y, Glessing B, Mallery S, Freeman ML. Endoscopic transluminal drainage and necrosectomy by using a novel, through-the-scope, fully covered, large-bore esophageal metal stent: preliminary experience in 10 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:312-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Sarkaria S, Sethi A, Rondon C, Lieberman M, Srinivasan I, Weaver K, Turner BG, Sundararajan S, Berlin D, Gaidhane M. Pancreatic necrosectomy using covered esophageal stents: a novel approach. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:145-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Bapaye A, Itoi T, Kongkam P, Dubale N, Mukai S. New fully covered large-bore wide-flare removable metal stent for drainage of pancreatic fluid collections: results of a multicenter study. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:499-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Rodrigues-Pinto E, Baron TH. Evaluation of the AXIOS stent for the treatment of pancreatic fluid collections. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2016;13:793-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Rinninella E, Kunda R, Dollhopf M, Sanchez-Yague A, Will U, Tarantino I, Gornals Soler J, Ullrich S, Meining A, Esteban JM. EUS-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections using a novel lumen-apposing metal stent on an electrocautery-enhanced delivery system: a large retrospective study (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:1039-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Chandran S, Efthymiou M, Kaffes A, Chen JW, Kwan V, Murray M, Williams D, Nguyen NQ, Tam W, Welch C. Management of pancreatic collections with a novel endoscopically placed fully covered self-expandable metal stent: a national experience (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:127-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 47. | Dhir V, Teoh AY, Bapat M, Bhandari S, Joshi N, Maydeo A. EUS-guided pseudocyst drainage: prospective evaluation of early removal of fully covered self-expandable metal stents with pancreatic ductal stenting in selected patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:650-657; quiz 718.e1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Shah RJ, Shah JN, Waxman I, Kowalski TE, Sanchez-Yague A, Nieto J, Brauer BC, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. Safety and efficacy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections with lumen-apposing covered self-expanding metal stents. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:747-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Walter D, Will U, Sanchez-Yague A, Brenke D, Hampe J, Wollny H, López-Jamar JM, Jechart G, Vilmann P, Gornals JB. A novel lumen-apposing metal stent for endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections: a prospective cohort study. Endoscopy. 2015;47:63-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Vazquez-Sequeiros E, Baron TH, Pérez-Miranda M, Sánchez-Yagüe A, Gornals J, Gonzalez-Huix F, de la Serna C, Gonzalez Martin JA, Gimeno-Garcia AZ, Marra-Lopez C. Evaluation of the short- and long-term effectiveness and safety of fully covered self-expandable metal stents for drainage of pancreatic fluid collections: results of a Spanish nationwide registry. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:450-457.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Bang JY, Hasan MK, Navaneethan U, Sutton B, Frandah W, Siddique S, Hawes RH, Varadarajulu S. Lumen-apposing metal stents for drainage of pancreatic fluid collections: When and for whom? Dig Endosc. 2017;29:83-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Siddiqui AA, Kowalski TE, Loren DE, Khalid A, Soomro A, Mazhar SM, Isby L, Kahaleh M, Karia K, Yoo J. Fully covered self-expanding metal stents versus lumen-apposing fully covered self-expanding metal stent versus plastic stents for endoscopic drainage of pancreatic walled-off necrosis: clinical outcomes and success. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:758-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Mukai S, Itoi T, Baron TH, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Kurihara T, Tsuchiya T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided placement of plastic vs. biflanged metal stents for therapy of walled-off necrosis: a retrospective single-center series. Endoscopy. 2015;47:47-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Sharaiha RZ, DeFilippis EM, Kedia P, Gaidhane M, Boumitri C, Lim HW, Han E, Singh H, Ghumman SS, Kowalski T. Metal versus plastic for pancreatic pseudocyst drainage: clinical outcomes and success. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:822-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Lee BU, Song TJ, Lee SS, Park DH, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. Newly designed, fully covered metal stents for endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided transmural drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections: a prospective randomized study. Endoscopy. 2014;46:1078-1084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Bang JY, Hawes R, Bartolucci A, Varadarajulu S. Efficacy of metal and plastic stents for transmural drainage of pancreatic fluid collections: a systematic review. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:486-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM. Endoscopic placement of permanent indwelling transmural stents in disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome: does benefit outweigh the risks? Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1408-1412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Téllez-Ávila FI, Casasola-Sánchez LE, Ramírez-Luna MÁ, Saúl Á, Murcio-Pérez E, Chan C, Uscanga L, Duarte-Medrano G, Valdovinos-Andraca F. Permanent Indwelling Transmural Stents for Endoscopic Treatment of Patients With Disconnected Pancreatic Duct Syndrome: Long-term Results. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Rasch S, Phillip V, Reichel S, Rau B, Zapf C, Rosendahl J, Halm U, Zachäus M, Müller M, Kleger A. Open Surgical versus Minimal Invasive Necrosectomy of the Pancreas-A Retrospective Multicenter Analysis of the German Pancreatitis Study Group. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Gardner TB, Chahal P, Papachristou GI, Vege SS, Petersen BT, Gostout CJ, Topazian MD, Takahashi N, Sarr MG, Baron TH. A comparison of direct endoscopic necrosectomy with transmural endoscopic drainage for the treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1085-1094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Seifert H, Biermer M, Schmitt W, Jürgensen C, Will U, Gerlach R, Kreitmair C, Meining A, Wehrmann T, Rösch T. Transluminal endoscopic necrosectomy after acute pancreatitis: a multicentre study with long-term follow-up (the GEPARD Study). Gut. 2009;58:1260-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Yasuda I, Nakashima M, Iwai T, Isayama H, Itoi T, Hisai H, Inoue H, Kato H, Kanno A, Kubota K. Japanese multicenter experience of endoscopic necrosectomy for infected walled-off pancreatic necrosis: The JENIPaN study. Endoscopy. 2013;45:627-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | van Brunschot S, Fockens P, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, Voermans RP, Poley JW, Gooszen HG, Bruno M, van Santvoort HC. Endoscopic transluminal necrosectomy in necrotising pancreatitis: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1425-1438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Mouli VP, Sreenivas V, Garg PK. Efficacy of conservative treatment, without necrosectomy, for infected pancreatic necrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:333-340.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Lakhtakia S, Basha J, Talukdar R, Gupta R, Nabi Z, Ramchandani M, Kumar BV, Pal P, Kalpala R, Reddy PM. Endoscopic “step-up approach” using a dedicated biflanged metal stent reduces the need for direct necrosectomy in walled-off necrosis (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Varadarajulu S, Noone TC, Tutuian R, Hawes RH, Cotton PB. Predictors of outcome in pancreatic duct disruption managed by endoscopic transpapillary stent placement. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:568-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Trevino JM, Tamhane A, Varadarajulu S. Successful stenting in ductal disruption favorably impacts treatment outcomes in patients undergoing transmural drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:526-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Jang JW, Kim MH, Oh D, Cho DH, Song TJ, Park DH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Moon SH. Factors and outcomes associated with pancreatic duct disruption in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2016;16:958-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Hookey LC, Debroux S, Delhaye M, Arvanitakis M, Le Moine O, Devière J. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic-fluid collections in 116 patients: a comparison of etiologies, drainage techniques, and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:635-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Shrode CW, Macdonough P, Gaidhane M, Northup PG, Sauer B, Ku J, Ellen K, Shami VM, Kahaleh M. Multimodality endoscopic treatment of pancreatic duct disruption with stenting and pseudocyst drainage: how efficacious is it? Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:129-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Yang D, Amin S, Gonzalez S, Mullady D, Hasak S, Gaddam S, Edmundowicz SA, Gromski MA, DeWitt JM, El Zein M. Transpapillary drainage has no added benefit on treatment outcomes in patients undergoing EUS-guided transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts: a large multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:720-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Arvanitakis M, Delhaye M, Bali MA, Matos C, De Maertelaer V, Le Moine O, Devière J. Pancreatic-fluid collections: a randomized controlled trial regarding stent removal after endoscopic transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:609-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Rana SS, Sharma R, Sharma V, Chhabra P, Gupta R, Bhasin DK. Prevention of recurrence of fluid collections in walled off pancreatic necrosis and disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome: Comparative study of one versus two long term transmural stents. Pancreatology. 2016;16:687-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Seewald S, Ang TL, Richter H, Teng KY, Zhong Y, Groth S, Omar S, Soehendra N. Long-term results after endoscopic drainage and necrosectomy of symptomatic pancreatic fluid collections. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:36-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Künzli HT, Timmer R, Schwartz MP, Witteman BJ, Weusten BL, van Oijen MG, Siersema PD, Vleggaar FP. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided drainage is an effective and relatively safe treatment for peripancreatic fluid collections in a cohort of 108 symptomatic patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:958-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Bapaye A, Dubale NA, Sheth KA, Bapaye J, Ramesh J, Gadhikar H, Mahajani S, Date S, Pujari R, Gaadhe R. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided transmural drainage of walled-off pancreatic necrosis: Comparison between a specially designed fully covered bi-flanged metal stent and multiple plastic stents. Dig Endosc. 2017;29:104-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Bang JY, Hasan M, Navaneethan U, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. Lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS) for pancreatic fluid collection (PFC) drainage: may not be business as usual. Gut. 2016; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Varadarajulu S. A hybrid endoscopic technique for the treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1015-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Yamamoto N, Isayama H, Takahara N, Sasahira N, Miyabayashi K, Mizuno S, Kawakubo K, Mohri D, Kogure H, Sasaki T. Percutaneous direct-endoscopic necrosectomy for walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Endoscopy. 2013;45 Suppl 2 UCTN:E44-E45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Navarrete C, Castillo C, Caracci M, Vargas P, Gobelet J, Robles I. Wide percutaneous access to pancreatic necrosis with self-expandable stent: new application (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:609-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Tringali A, Thomson M, Dumonceau JM, Tavares M, Tabbers MM, Furlano R, Spaander M, Hassan C, Tzvinikos C, Ijsselstijn H. Pediatric gastrointestinal endoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Guideline Executive summary. Endoscopy. 2017;49:83-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Ramesh J, Bang JY, Trevino J, Varadarajulu S. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:30-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Lakhtakia S, Agarwal J, Gupta R, Ramchandani M, Kalapala R, Nageshwar Reddy D. EUS-guided transesophageal drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections in children. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:587-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Jazrawi SF, Barth BA, Sreenarasimhaiah J. Efficacy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts in a pediatric population. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:902-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Bang JY, Varadarajulu S. Endoscopic Treatment of Walled-off Necrosis in Children: Clinical Experience and Treatment Outcomes. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63:e31-e35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Nabi Z, Lakhtakia S, Basha J, Chavan R, Ramchandani M, Gupta R, Kalapala R, Darisetty S, Talukdar R, Reddy DN. Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Drainage of Walled-off Necrosis in Children With Fully Covered Self-expanding Metal Stents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64:592-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |