Published online Mar 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i11.2068

Peer-review started: December 20, 2016

First decision: February 9, 2017

Revised: February 15, 2017

Accepted: March 2, 2017

Published online: March 21, 2017

Processing time: 91 Days and 0 Hours

To investigate the detrimental impact of loss of reservoir capacity by comparing total gastrectomy (TGRY) and distal gastrectomy with the same Roux-en-Y (DGRY) reconstruction. The study was conducted using an integrated questionnaire, the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale (PGSAS)-45, recently developed by the Japan Postgastrectomy Syndrome Working Party.

The PGSAS-45 comprises 8 items from the Short Form-8, 15 from the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale, and 22 newly selected items. Uni- and multivariate analysis was performed on 868 questionnaires completed by patients who underwent either TGRY (n = 393) or DGRY (n = 475) for stage I gastric cancer (52 institutions). Multivariate analysis weighed of six explanatory variables, including the type of gastrectomy (TGRY/DGRY), interval after surgery, age, gender, surgical approach (laparoscopic/open), and whether the celiac branch of the vagus nerve was preserved/divided on the quality of life (QOL).

The patients who underwent TGRY experienced the poorer QOL compared to DGRY in the 15 of 19 main outcome measures of PGSAS-45. Moreover, multiple regression analysis indicated that the type of gastrectomy, TGRY, most strongly and broadly impaired the postoperative QOL among six explanatory variables.

The results of the present study suggested that TGRY had a certain detrimental impact on the postoperative QOL, and the loss of reservoir capacity could be a major cause.

Core tip: The influence of postgastrectomy syndrome after total gastrectomy (TG) is believed to be more intense than that after distal gastrectomy (DG). However, the precise features and the degree of interference with quality of life after TG against DG have not been clarified. Then, we weighed DG against TG to determine pure influence of whether presence or absence of remaining stomach (as the reservoir capacity) by employing the same reconstruction route. Moreover, we reinforced the findings by multivariable analysis including other clinical factors, and defined the effect sizes of each variable in the unprecedented examination with large number cases using newly developed Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-45.

- Citation: Takahashi M, Terashima M, Kawahira H, Nagai E, Uenosono Y, Kinami S, Nagata Y, Yoshida M, Aoyagi K, Kodera Y, Nakada K. Quality of life after total vs distal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction: Use of the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-45. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(11): 2068-2076

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i11/2068.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i11.2068

The five-year overall survival rate of stage I gastric cancer patients who undergo gastrectomy with sufficient lymphadenectomy has been shown to exceed 90% in Japan[1]. Maintaining quality of life (QOL) after surgery is an important issue for patients who are eventually cured, and several surgical procedures have been developed to minimize the influence of postgastrectomy syndromes (PGS).

The severity of PGS after total gastrectomy (TG) is clinically recognized to be greater than after distal gastrectomy (DG). And a functional analysis has demonstrated the significant interrelationship between weight loss and esophageal bile reflux after TG[2]. Recently, combined questionnaires using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-STO22 have demonstrated the differences of several upper-gastrointestinal symptoms associated with distal, proximal and total gastrectomy[3]. However, other study using same combined QOL questionnaires have failed to reveal significant differences in QOL scores[4] among them. Such a discrepancy may have arisen from a lack of adequate instruments for evaluating the QOL in the postgastrectomy patients.

The Japan Postgastrectomy Syndrome Working Party (JPSWP) was founded to more closely investigate the symptoms and lifestyle changes of patients who had undergone gastrectomy. This group collaboratively developed a novel questionnaire [Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale (PGSAS)-45] to evaluate the symptoms, living status, and QOL of gastrectomized patients[5]. In this study, we firstly focused the strength and extent of detrimental impact of TG against DG, in which the reservoir capacity is maintained by the remaining stomach, with the same Roux-en-Y reconstruction route, using multi-variate analyses including other clinical factors influencing QOL[6].

The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) a pathologically confirmed diagnosis of stage IA or IB gastric cancer[7]; (2) first-time gastrectomy status; (3) age between ≥ 20 and ≤ 75 years; (4) no history of chemotherapy; (5) no evidence of recurrence or distant metastasis; (6) gastrectomy conducted ≥ 1 year prior to study enrollment; (7) performance status (PS) ≤ 1 on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale; (8) full ability to understand and respond to the questionnaire; (9) no history of other diseases or surgeries that might influence responses to the questionnaire; (10) absence of organ failure or mental illness; and (11) provision of written informed consent. The exclusion criteria included patients who had an additional malignancy and patients who underwent the concomitant resection of other organs (except for cholecystectomy or splenectomy).

PGSAS-45 is a newly developed, multidimensional QOL questionnaire (QLQ) consists of a total of 45 questions, with 8 items from the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-8)[8], 15 items from the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS)[9], and 22 clinically important items selected by the JPSWP5. These important items consists of newly selected 10 PGSAS specific items for symptoms (items 24-33), eight questionnaire items pertain to dietary intake (items 34-41), one item for social activity (item 42) and three items about level of satisfaction with daily life (items 43-45). For the 23 symptom items, a seven-grade (1-7) Likert scale was used. A five-grade (1-5) Likert scale was used for all the other items, except for items 1, 4, 29, 32, and 34-37. For items 1-8, 34, 35, and 38-40, higher scores indicate better conditions. For items 9-28, 30, 31, 33, and 41-45, higher scores indicate worse conditions.

This study utilized continuous sampling from a central registration system for participant enrollment. The questionnaire was distributed to all eligible patients as they presented at the participating clinics. The patients were instructed to mail the completed questionnaires directly to the data center. All the QOL data from the questionnaires were matched with individual patient data collected via case report forms (CRFs) sent from the physicians in charge of the patients and stored in a database.

This study was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network’s Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN-CTR; registration number 000002116). The study was approved by local ethics committees at each institution. Written informed consent was obtained from all the enrolled patients.

PGSAS-45 questionnaires were distributed to 2922 patients between July 2009 and December 2010. Among the 2520 (86%) patients who returned completed questionnaires, 152 were determined to be ineligible because of age (older than 75 years, n = 90), postoperative period > 1 year (n = 29), resection of other organs (n = 8), or other factors (n = 25). The data and responses from the remaining 2368 patients (81%) were eligible for subsequent analyses. In the current study, data from 868 patients who underwent either total gastrectomy (TGRY, n = 393) or distal gastrectomy (DGRY, n = 475), all with Roux-en-Y reconstruction, were retrieved from the database and analyzed. Other data from 1500 patients who underwent distal gastrectomy with Billroth-I reconstruction (DGBI, n = 909), pylorus preserving gastrectomy (PPG, n = 313, proximal gastrectomy (PG, n = 193) or local resection (LR, n = 85) were excluded for this study.

Based on the data from the completed PGSAS-45 questionnaires, the outcome measures were refined by consolidation and selection[5]. The 23 symptom items were consolidated into the 7 symptom subscales (SS) listed in Table 1. The main outcome measures for the assessment data included several subscales such as the total symptom score, quality of ingestion, level of dissatisfaction for daily life, a physical component summary (PCS) based on items derived from the SF-8, and a mental component summary (MCS), also based on SF-8 items. Each SS score, except the PCS and MCS, was calculated as the mean of the composed items, and the total symptom score was calculated as the mean of seven symptom SSs. In addition, the following parameters were selected as the main outcome measures: body weight changes, amount of food ingested per meal, necessity for additional meals, ability for working, dissatisfaction with symptoms, dissatisfaction at the meals, and dissatisfaction at working.

| Domains | Subdomains | Main outcome measures | TGRY | DGRY | Uni-variate analysis | |||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | P value | Cohen's d | |||

| Symptoms | PGSAS subscales (GSRS and PGSAS items) | Esophageal reflux subscale (items 10, 11, 13, 24)2 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 0.7 | < 0.0001 | 0.58 |

| Abdominal pain subscale (items 9, 12, 28)2 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 0.0571 | (0.13) | ||

| Meal-related distress subscale (items 25-27)2 | 2.6 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 0.9 | < 0.0001 | 0.56 | ||

| Indigestion subscale (items 14-17)2 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 0.8 | < 0.0001 | 0.29 | ||

| Diarrhea subscale (items 19, 20, 22)2 | 2.3 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 0.0066 | (0.19) | ||

| Constipation subscale (items 18, 21, 23)2 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 1.0 | ≥ 0.1 | |||

| Dumping subscale (items 30, 31, 33)2 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | < 0.0001 | 0.31 | ||

| Total | Total symptom score (above seven subscales)2 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 0.7 | < 0.0001 | 0.38 | |

| Living status | Body weight | Change in body weight | -13.8% | 7.9% | -8.9% | 6.6% | < 0.0001 | 0.66 |

| Meals(amount) | Ingested amount of food per meal | 6.4 | 1.9 | 7.2 | 2.0 | < 0.0001 | 0.42 | |

| Necessity for additional meals | 2.4 | 0.8 | 1.9 | 0.8 | < 0.0001 | 0.57 | ||

| Meals (quality) | Quality of ingestion subscale1 (items 38-40)2 | 3.8 | 0.9 | 3.8 | 0.9 | ≥ 0.1 | ||

| Social activity | Ability for working | 2.0 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.0006 | 0.24 | |

| QOL | Dissatisfaction | Dissatisfaction with symptoms | 2.1 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 0.9 | < 0.0001 | 0.28 |

| Dissatisfaction at the meal | 2.8 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.1 | < 0.0001 | 0.57 | ||

| Dissatisfaction at working | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.0 | < 0.0001 | 0.41 | ||

| Dissatisfaction for daily life subscale (items 43-45)2 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 0.9 | < 0.0001 | 0.51 | ||

| SF-8 | Physical component summary (PCS)1 (items 1-8)2 | 49.6 | 5.6 | 50.8 | 5.6 | 0.0029 | 0.21 | |

| Mental component summary (MCS)1 (items 1-8)2 | 49.2 | 6.0 | 49.8 | 5.7 | 0.0974 | (0.11) | ||

| The interpretation of effect size | Cohen's d | |||||||

| (none-very small) | (0.20 >) | |||||||

| Small | 0.20 ≤ | |||||||

| Medium | 0.50 ≤ | |||||||

| Large | 0.80 ≤ | |||||||

In comparing patient QOLs after TGRY and DGRY, statistical methods included the t-test and χ2 test. All outcome measures that exhibited significant difference in univariate analysis were further analyzed using multiple regression analysis to eliminate confounding factors by adding time interval from surgery, age, gender, surgical approach, and celiac branch preservation to the type of gastrectomy. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. In the case of P < 0.1 by univariate analysis, Cohen’s d was calculated. In the case of that P value of standardized regression coefficient (β) in multiple regression analysis was < 0.1, the β value has shown in the table. Cohen’s d, β, and R2 (coefficient of determination) measure effect sizes. Interpretation of effect sizes were 0.2 < small, 0.5 < medium, and 0.8 < large in Cohen’s d; 0.1 < small, 0.3 < medium, and 0.5 < large in β; and 0.02 < small, 0.13 < medium, and 0.26 < large in R2. StatView software for Windows Ver. 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc.) was used for all statistical analyses.

The demographics of all the study participants enrolled from 52 institutions are listed in Table 2. Among the patients who underwent TGRY, the time interval from surgery until the current evaluation and the length of the Roux segment were significantly longer; age, incidence of applying an open approach, extent of lymph node dissection, and combined resection rate were significantly higher; and a posterior route of Roux-en-Y was significantly more common.

| TGRY | DGRY | P value | ||

| Number of patients | 393 | 475 | ||

| Postoperative period | (mo) | 35.0 ± 24.61 | 31.7 ± 18.01 | 0.02464 |

| Age | 63.4 ± 9.21 | 62.0 ± 9.11 | 0.02444 | |

| Gender | Male | 276 | 318 | ≥ 0.15 |

| Female | 113 | 154 | ||

| Preoperative BMI2 | 23.0 ± 3.31 | 22.9 ± 3.01 | ≥ 0.14 | |

| Postoperative BMI2 | 19.8 ± 2.51 | 20.8 ± 2.71 | < 0.00014 | |

| Approach | Open | 293 | 320 | 0.01815 |

| Laparoscopic | 97 | 152 | ||

| Extent of lymph node | D0 | 0 | 0 | 0.01595 |

| dissection3 | D1 | 4 | 3 | |

| D1a | 28 | 60 | ||

| D1b | 192 | 246 | ||

| D2 | 164 | 163 | ||

| Celiac branch of vagal nerve | Preserved | 12 | 28 | 0.05235 |

| Divided | 371 | 442 | ||

| Combined resection | None | 246 | 402 | < 0.00015 |

| Gallbladder | 83 | 51 | ||

| spleen | 52 | 2 | ||

| Miscellaneous | 4 | 2 | ||

| Length of Roux-en-Y loop | (cm) | 42 ± 4.21 | 32.2 ± 7.11 | < 0.00014 |

| Route of Roux-en-Y | Anterior | 179 | 292 | < 0.00014 |

| Posterior | 206 | 175 |

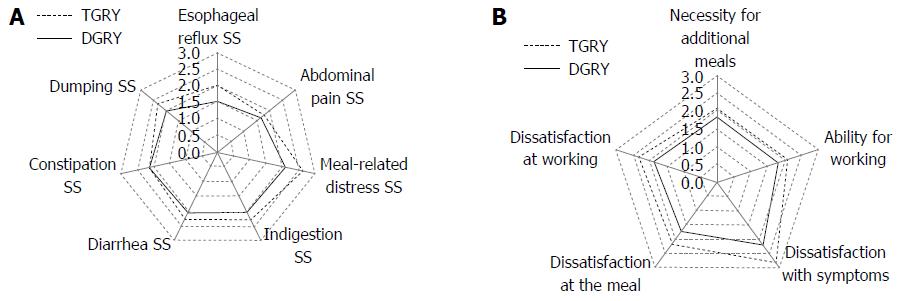

PGSAS symptom subscales: Twenty-three symptom items comprising items derived from the GSRS and original items proposed and selected by the participating gastric surgeons during the establishment of the PGSAS were consolidated into seven symptom SSs (i.e., the PGSAS symptom SSs). These SSs reflected the PGS symptom profile and revealed that the patients who underwent TGRY had significantly higher (i.e., worse) scores (Table 1 and Figure 1A). The implication of the type of gastrectomy on each PGSAS symptom SS, in terms of effect size “Cohen’s d”, is shown in Table 1. To eliminate confounding factors, a multiple regression analysis was performed by adding the time interval from surgery, age, gender, surgical approach, and celiac branch preservation as explanatory variables. Cohen’s d (by the univariate analysis) and β (by the multiple regression analysis) of the esophageal reflux SS, meal-related distress SS, indigestion SS and dumping SS were significantly declined by the extent of gastrectomy with medium to small effect size (e.g., Cohen’s d and β, Tables 1 and 3).

| Main outcome measures | Multiple regression analysis | |||||||||||||||

| Domains | Subdomains | Type of gastrectomy [TGRY] | Postoperative period (mo) | Age (yr) | Gender [male] | Approach [laparoscopic] | Celiac branch of vagal nerve [preserved] | |||||||||

| β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | R2 | P value | |||

| Symptoms | Subscales (GSRS and PGSAS items) | Esophageal reflux SS2 | 0.298 | < 0.0001 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | (-0.079) | 0.0179 | (-0.060) | 0.0828 | ≥ 0.1 | 0.096 | < 0.0001 | |||

| Abdominal pain SS2 | (-0.089) | 0.0096 | (-0.060) | 0.0932 | ≥ 0.1 | -0.181 | < 0.0001 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | 0.045 | < 0.0001 | |||||

| Meal-related distress SS2 | 0.295 | < 0.0001 | ≥ 0.1 | (-0.064) | 0.0531 | -0.114 | 0.0006 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | 0.101 | < 0.0001 | |||||

| Indigestion SS2 | 0.166 | < 0.0001 | -0.114 | 0.0012 | ≥ 0.1 | (-0.083) | 0.0138 | (-0.071) | 0.0436 | (-0.063) | 0.0639 | 0.057 | < 0.0001 | |||

| Diarrhea SS2 | 0.107 | 0.0020 | (-0.063) | 0.0774 | ≥ 0.1 | (-0.092) | 0.0074 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | 0.024 | 0.0026 | |||||

| Constipation SS2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Dumping SS2 | 0.189 | < 0.0001 | ≥ 0.1 | -0.123 | 0.0006 | -0.129 | 0.0003 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | 0.071 | < 0.0001 | |||||

| Total | Total symptom score2 | 0.216 | < 0.0001 | ≥ 0.1 | > 0.1 | (-0.092) | 0.0115 | ≥ 0.1 | > 0.1 | 0.059 | < 0.0001 | |||||

| Living status | Body weight | Change in body weight | 0.315 | < 0.0001 | ≥ 0.1 | (-0.068) | 0.0449 | (-0.088) | 0.0086 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | 0.114 | < 0.0001 | |||

| Meals (amount) | Ingested amount of food per meal1 | 0.202 | < 0.0001 | ≥ 0.1 | (-0.060) | 0.0838 | > 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | 0.048 | < 0.0001 | |||||

| Necessity for additional meals | 0.273 | < 0.0001 | ≥ 0.1 | -0.083 | 0.0142 | (-0.093) | 0.0057 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | 0.090 | < 0.0001 | |||||

| Meals (quality) | Quality of ingestion SS1,2 | |||||||||||||||

| Social activity | Ability for working | 0.127 | 0.0003 | (-0.079) | 0.0289 | 0.163 | < 0.0001 | (-0.073) | 0.0371 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | 0.052 | < 0.0001 | |||

| QOL | Dissatisfaction | Dissatisfaction with symptoms | 0.158 | < 0.0001 | (-0.083) | 0.0199 | ≥ 0.1 | -0.105 | 0.0022 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | 0.041 | < 0.0001 | |||

| Dissatisfaction at the meal | 0.291 | < 0.0001 | (-0.081) | 0.0193 | ≥ 0.1 | (-0.072) | 0.0313 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | 0.093 | < 0.0001 | |||||

| Dissatisfaction at working | 0.220 | < 0.0001 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | > 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | 0.051 | < 0.0001 | |||||||

| Dissatisfaction for daily life SS2 | 0.268 | < 0.0001 | (-0.086) | 0.0145 | ≥ 0.1 | (-0.087) | 0.0097 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | 0.083 | < 0.0001 | |||||

| SF-8 | Physical component summary1,2 | 0.109 | 0.0016 | ≥ 0.1 | -0.124 | 0.0004 | (-0.079) | 0.0210 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | 0.034 | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Mental component summary1,2 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | ≥ 0.1 | ||||||||||

| The interpretation of effect size | r, β | R2 | ||||||||||||||

| (none-very small) | (0.100) > | (0.020) > | ||||||||||||||

| Small | 0.100 ≤ | 0.020 ≤ | ||||||||||||||

| Medium | 0.300 ≤ | 0.130 ≤ | ||||||||||||||

| Large | 0.500 ≤ | 0.260 ≤ | ||||||||||||||

The total symptom score, which aggregated all seven PGSAS symptom SSs, denoted the severity of overall PGS symptom and its values of Cohen’s d, β, and R2 in the present study were 0.38, 0.216, and 0.059, respectively. This also indicated that the severity of overall PGS symptom after TGRY were significantly greater than those after DGRY (Tables 1 and 3).

Body weight changes: The body weight change more than one year after gastrectomy was -13.8% in the patients who underwent TGRY and -8.9% in those who underwent DGRY. The type of gastrectomy had a significant and medium implication on body weight loss as to effect size; the uni-variate analysis produced a Cohen’s d of 0.66 (Table 1), and the multiple regression analysis produced a β of 0.315 (Table 3).

Meals, social activity, and dissatisfaction: The ingested amount of food per meal, necessity for additional meals, ability for working, and dissatisfaction with symptoms at the meal and at working were important items included in the PGSAS-45. The scores on these items revealed that the patients who underwent TG experienced significantly worse living status and more dissatisfaction for their lives (Table 1 and Figure 1B).

The Cohen’s d values for the necessity for additional meals, dissatisfaction at the meal and dissatisfaction for daily life SS were of medium effect size. All the other items related to dissatisfaction had small Cohen’s d values, indicating that they were significantly influenced by the type of gastrectomy with small but clinically meaningful effect size (Tables 1 and 3). The dissatisfaction for daily life SS, which consisted of three dissatisfaction items, demonstrated a significant influence of PGS. The Cohen’s d, β, and R2 values for this SS were 0.51, 0.268, and 0.083, respectively (Tables 1 and 3).

SF-8: The SF-8, a useful and simple questionnaire for evaluating generic QOL, includes PCS and MCS as SSs. For the PCS, Cohen’s d was 0.21, and β was 0.109. Thus, the PCS was significantly lower in the TGRY cases (with a small effect size), whereas the MCS did not differ between the TGRY and DGRY cases (Tables 1 and 3).

This study aimed to compare the effects of TGRY and DGRY on postoperative QOL in gastric cancer patients. This comparison was performed using the PGSAS-45, a questionnaire developed to measure QOL in postgastrectomy patients. In the series of our cross-sectional study, we found that there was a little difference in the effect after DG between Billroth-I and Roux-en-Y procedure[10]. On the other hand, several clinical factors such as symptom severity, ability for working, and necessity for additional meals had a significant impact on postoperative QOL, while the influence of the extent of gastrectomy was unexpectedly small[6].

The influence of postgastrectomy syndrome is believed to be more intense after TG than after DG. However, the reasons for and degree of interference with QOL after TG vs DG have not been clarified. Most of prior reports compared the postoperative QOL between TG with Roux-en-Y and DG mainly with Billroth-I or II, in which the food or digestive juice passes through the other route[11,12]. Therefore, the detected differences between TG and DG in the previous studies may have designated the aggregated effect of both the preservation of proximal stomach and the reconstruction route. This study compared TGRY with DGRY to determine the pure influence of the remaining stomach (which approximates reservoir capacity).

Our results showed apparent differences in several main outcome measures associated with symptoms, daily living, and QOL. In multivariate analysis, 15 of 19 main outcome measures (with the exception of the constipation SS, indigestion SS, quality of ingestion SS and MCS) indicated significantly inferior conditions in the TGRY group. To identify which outcomes were most declined by the complete loss of reservoir capacity in TGRY, the effect sizes of these main outcome measures were compared. The variables shown to be adversely affected were (in decreasing order of severity) body weight loss, esophageal reflux SS, meal-related distress SS, dissatisfaction with meals, necessity for additional meals, and dissatisfaction with daily life SS. Thus, the PGSAS-45 was able to demonstrate the multifaceted influences on life conditions of total or distal gastrectomy.

Several reports have postulated that preserving the lower esophageal sphincter or cardia prevents esophageal reflux[11,12]. Moreover, esophageal reflux has been less frequently observed following DGRY than after DGBI[8,13-18]. Thus, preserving the proximal stomach with Roux-en-Y reconstruction should help to prevent esophageal reflux. A proximal gastrectomy is regarded as a potent alternative to avoid the serious detrimental impact of TG for early upper-third gastric cancer patients. Indeed, the recent study using the PGSAS-45 questionnaire revealed that proximal gastrectomy appeared to be valuable as a function-preserving procedure, however, declined the majority of symptom SSs such as esophageal reflux, abdominal pain, meal-related distress and ingestion in the same way as TG[19]. Another alternative to avoid the severe impairment of QOL after TG is to constitute the substitute stomach. Although Fein et al[20] and Iivonen et al[21] reported long-term benefits of RY pouch reconstruction after TG, there is no universal consensus regarding the optimal method of reconstruction following TG. A meta-analysis demonstrated several clinical advantages of pouch reconstruction after TG; patients with a pouch reportedly complained significantly less of dumping and heartburn, and they exhibited a significantly better postoperative food intake[22]. Thus, maintaining reservoir function after gastrectomy appears to be of utmost importance.

Further validation of our findings by prospective clinical trials using the PGSAS-45 for assessments at baseline and at various relevant time points is warranted.

Several investigators have assessed QOL following TG and have compared various surgical and reconstructive procedure[22], however, no large-scale QOL comparisons of TG and DG performed with the same reconstruction procedure, Roux-en-Y, have been published to date. The current study has the intrinsic limitation of being a retrospective study. Moreover, the patient-reported outcomes were assessed at a single time point, which could be any time at least one year after surgery. Nevertheless, the postoperative conditions of the patients more than one year after gastrectomy were generally stable[23], and the multivariate analysis identified that the type of gastrectomy (TGRY vs DGRY) was the factor with the greatest influence on several of the main outcome measures. The current study represents the first large-scale investigation of patient QOL following gastrectomy using the PGSAS-45 questionnaire with multivariate analysis.

In this study, the PGSAS-45 defined a certain impairment of QOL after TGRY compared to DGRY specifically. Therefore, it is important to closely monitor patients to enable early detection and management of PGS, and to provide appropriate nutritional support. The results of the present study defined that the sole loss of remaining stomach strongly and broadly impairs the QOL in postgastrectomy patients. This may suggest that reservoir reconstruction using a stomach substitute should be an optional alternative to maintain better QOL after TG.

This study was conducted by the JPGSWP and is registered at UMIN-CTR No. 000002116 as “A study to observe correlation between resection and reconstruction procedures employed for gastric neoplasms and development of postgastrectomy syndrome”. The results of this study were presented at the 2013 International Gastric Cancer Congress in Verona, Italy.

The authors thank all the physicians who participated in this study and the patients whose cooperation made this study possible.

The influence of postgastrectomy syndrome (PGS) after total gastrectomy (TG) is believed to be more intense than that after distal gastrectomy (DG). However, the precise features and the degree of interference with quality of life (QOL) after TG against DG have not been clarified. It was discussed by a comparison between TG and DG in the past report, however, even if it was the same DG. Most of prior reports compared the postoperative QOL between TG with Roux-en-Y (RY) and DG mainly with Billroth-I (BI) or II (BII), in which the food or digestive juice passes through the other route. Therefore, influence due to the physiological reconstruction might be mixed in the difference of both as well as influence of TG with RY (TGRY).

Most of prior reports compared the postoperative QOL between TG with RY and DG mainly with BI or BII, in which the food or digestive juice passes through the other route. Several reports have postulated that preserving the lower esophageal sphincter or cardia prevents esophageal reflux. Moreover, esophageal reflux has been less frequently observed following DGRY than after DGBI. Thus, preserving the proximal stomach with Roux-en-Y reconstruction should help to prevent esophageal reflux.

This study was to have compared the DG with TG except influence of the reconstruction course. And we examined influence of the presence or absence of reservoir capacity by multivariable analysis including other clinical factors, and showed the statistical effect sizes. Moreover, this study was unprecedented examination with large number cases and used newly developed PGSAS-45 questionnaire evaluating patient QOL following gastrectomy. The PGSAS-45 defined a certain impairment of QOL after TGRY compared to DGRY specifically. Therefore, it is important to closely monitor patients to enable early detection and management of PGS, and to provide appropriate nutritional support. The results of the present study defined that the sole loss of remaining stomach strongly and broadly impairs the QOL in postgastrectomy patients.

The study results suggest that reservoir reconstruction using a stomach substitute should be an optional alternative to maintain better QOL after TG.

Postgastrectomy syndrome is a group of disorders and complications following gastrectomy. It includes early dumping syndrome, late dumping syndrome, bile reflux gastritis, afferent loop syndrome, efferent loop syndrome, Roux syndrome, postvagotomy diarrhea, malabsorption, anemia, osteoporosis, gastroparesis, and weight loss.

The authors have conducted a well-written study based on sound methods. The manuscript flows easily and with clarity. The case selection and choice of the important variables were appropriate and clinically relevant. The graphs and the tables are to the point and summarizing the main results of the study in an appropriate fashion. The retrospective nature limits the study, and the analysis would benefit from a propensity score matching to match the cases better and hence give stronger inference.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Bekheit M, Kehagias IG S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Nashimoto A, Akazawa K, Isobe Y, Miyashiro I, Katai H, Kodera Y, Tsujitani S, Seto Y, Furukawa H, Oda I. Gastric cancer treated in 2002 in Japan: 2009 annual report of the JGCA nationwide registry. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:1-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Adachi S, Takeda T, Fukao K. Evaluation of esophageal bile reflux after total gastrectomy by gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary dual scintigraphy. Surg Today. 1999;29:301-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Karanicolas PJ, Graham D, Gönen M, Strong VE, Brennan MF, Coit DG. Quality of life after gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma: a prospective cohort study. Ann Surg. 2013;257:1039-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rausei S, Mangano A, Galli F, Rovera F, Boni L, Dionigi G, Dionigi R. Quality of life after gastrectomy for cancer evaluated via the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-STO22 questionnaires: surgical considerations from the analysis of 103 patients. Int J Surg. 2013;11 Suppl 1:S104-S109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nakada K, Ikeda M, Takahashi M, Kinami S, Yoshida M, Uenosono Y, Kawashima Y, Oshio A, Suzukamo Y, Terashima M. Characteristics and clinical relevance of postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale (PGSAS)-45: newly developed integrated questionnaires for assessment of living status and quality of life in postgastrectomy patients. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:147-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nakada K, Takahashi M, Ikeda M, Kinami S, Yoshida M, Uenosono Y, Kawashima Y, Nakao S, Oshio A, Suzukamo Y. Factors affecting the quality of life of patients after gastrectomy as assessed using the newly developed PGSAS-45 scale: A nationwide multi-institutional study. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8978-8990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1723] [Cited by in RCA: 1896] [Article Influence: 135.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Turner-Bowker DM, Bayliss MS, Ware JE, Kosinski M. Usefulness of the SF-8 Health Survey for comparing the impact of migraine and other conditions. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:1003-1012. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Svedlund J, Sjödin I, Dotevall G. GSRS--a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:129-134. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Terashima M, Tanabe K, Yoshida M, Kawahira H, Inada T, Okabe H, Urushihara T, Kawashima Y, Fukushima N, Nakada K. Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale (PGSAS)-45 and changes in body weight are useful tools for evaluation of reconstruction methods following distal gastrectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21 Suppl 3:S370-S378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Park S, Chung HY, Lee SS, Kwon O, Yu W. Serial comparisons of quality of life after distal subtotal or total gastrectomy: what are the rational approaches for quality of life management? J Gastric Cancer. 2014;14:32-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Davies J, Johnston D, Sue-Ling H, Young S, May J, Griffith J, Miller G, Martin I. Total or subtotal gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma? A study of quality of life. World J Surg. 1998;22:1048-1055. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402:656-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5961] [Cited by in RCA: 5889] [Article Influence: 226.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tomita R, Sakurai K, Fujisaki S, Shibata M. Manometric study in patients with or without preserved lower esophageal sphincter 2 years or more after total gastrectomy reconstructed by Roux-en-Y for gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:2339-2342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim J, Kim S, Min YD. Consideration of cardia preserving proximal gastrectomy in early gastric cancer of upper body for prevention of gastroesophageal reflux disease and stenosis of anastomosis site. J Gastric Cancer. 2012;12:187-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ishikawa M, Kitayama J, Kaizaki S, Nakayama H, Ishigami H, Fujii S, Suzuki H, Inoue T, Sako A, Asakage M. Prospective randomized trial comparing Billroth I and Roux-en-Y procedures after distal gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. World J Surg. 2005;29:1415-1420; discussion 1421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hirao M, Takiguchi S, Imamura H, Yamamoto K, Kurokawa Y, Fujita J, Kobayashi K, Kimura Y, Mori M, Doki Y. Comparison of Billroth I and Roux-en-Y reconstruction after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: one-year postoperative effects assessed by a multi-institutional RCT. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1591-1597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee MS, Ahn SH, Lee JH, Park DJ, Lee HJ, Kim HH, Yang HK, Kim N, Lee WW. What is the best reconstruction method after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer? Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1539-1547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Takiguchi N, Takahashi M, Ikeda M, Inagawa S, Ueda S, Nobuoka T, Ota M, Iwasaki Y, Uchida N, Kodera Y. Long-term quality-of-life comparison of total gastrectomy and proximal gastrectomy by postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale (PGSAS-45): a nationwide multi-institutional study. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:407-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fein M, Fuchs KH, Thalheimer A, Freys SM, Heimbucher J, Thiede A. Long-term benefits of Roux-en-Y pouch reconstruction after total gastrectomy: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2008;247:759-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Iivonen MK, Mattila JJ, Nordback IH, Matikainen MJ. Long-term follow-up of patients with jejunal pouch reconstruction after total gastrectomy. A randomized prospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:679-685. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Gertler R, Rosenberg R, Feith M, Schuster T, Friess H. Pouch vs. no pouch following total gastrectomy: meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2838-2851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kobayashi D, Kodera Y, Fujiwara M, Koike M, Nakayama G, Nakao A. Assessment of quality of life after gastrectomy using EORTC QLQ-C30 and STO22. World J Surg. 2011;35:357-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |