Published online Mar 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i11.2029

Peer-review started: November 15, 2016

First decision: December 19, 2016

Revised: December 30, 2016

Accepted: January 11, 2017

Article in press: January 11, 2017

Published online: March 21, 2017

Processing time: 127 Days and 1.9 Hours

To investigate compliance with transanal irrigation (TAI) one year after a training session and to identify predictive factors for compliance.

The compliance of one hundred eight patients [87 women and 21 men; median age 55 years (range 18-83)] suffering from constipation or fecal incontinence (FI) was retrospectively assessed. The patients were trained in TAI over a four-year period at a single institution. They were classified as adopters if they continued using TAI for at least one year after beginning the treatment or as non-adopters if they stopped. Predictive factors of compliance with TAI were based on pretreatment assessments and training progress. The outcomes of the entire cohort of patients who had been recruited for the TAI treatment were expressed in terms of intention-to-treat.

Forty-six of the 108 (43%) trained patients continued to use TAI one year after their training session. The patients with FI had the best results, with 54.5% remaining compliant with TAI. Only one-third of the patients who complained of slow transit constipation or obstructed defecation syndrome continued TAI. There was an overall discontinuation rate of 57%. The most common reason for discontinuing TAI was the lack of efficacy (41%). However, 36% of the patients who discontinued TAI gave reasons independent of the efficacy of the treatment such as technical problems (catheter expulsion, rectal balloon bursting, instilled water leakage or retention, pain during irrigation, anal bleeding, anal fissure) while 23% said that there were too many constraints. Of the patients who reported discontinuing TAI, the only predictive factor was the progress of the training (OR = 4.9, 1.3-18.9, P = 0.02).

The progress of the training session was the only factor that predicted patient compliance with TAI.

Core tip: Less than 50% of the trained patients continued to use transanal irrigation (TAI) for the treatment of their defecation disorders one year after their training sessions. We showed for the first time that the only predictive factor for TAI discontinuation was the progress of the training. This suggested that the first training session should be better structured in order to promote more realistic expectations of treatment efficacy, side-effects, and constraints in order to reduce the discontinuation rate.

- Citation: Bildstein C, Melchior C, Gourcerol G, Boueyre E, Bridoux V, Vérin E, Leroi AM. Predictive factors for compliance with transanal irrigation for the treatment of defecation disorders. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(11): 2029-2036

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i11/2029.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i11.2029

Chronic constipation and fecal incontinence (FI) are common disorders with debilitating symptoms[1,2]. There is a hierarchy of management strategies for constipation and FI. Conservative (education, behavioral therapy, biofeedback) and pharmacological (oral and rectal laxatives) management measures are effective for most constipation and FI patients[1,2]. However, when these measures fail to control symptoms, additional strategies, including transanal irrigation (TAI), are required to improve symptoms and quality of life. TAI involves the instillation of water into the colon and rectum using a disposable balloon catheter. The water and the contents of the descending colon, sigmoid, and rectum are then evacuated in a controlled manner[3]. TAI was first introduced into clinical practice by Shandling and Gilmour for children with neurogenic bowel dysfunction (NBD) related to spina bifida[3]. Based on its clinical efficacy in treating children with NBD, TAI was then applied to adults with NBD[4] and to children and adults with functional bowel disorders for whom traditional treatments had failed[5]. While short-term trials indicated that constipation and FI are significantly improved by TAI, compliance is difficult to maintain over time[6,7]. The predictive factors of mid-term and long-term compliance with TAI in adults have been poorly described to date[6,7].

The purposes of the present study were (1) to investigate compliance with TAI of adults suffering from constipation or FI; and (2) to identify specific predictive factors of compliance with TAI based on pretreatment assessments and training progress.

A retrospective review of adult patients with constipation or FI refractory to first-line treatments and their compliance with a Peristeen® TAI (Coloplast A/S, 3050 Humlebæk, Denmark) bowel management program over a four-year period (2010-2014) in a single institution was conducted. There were no predefined physiological, radiological, or psychosocial criteria to propose TAI to patients except the failure of the first-line treatment (education, behavioral therapy, biofeedback, oral and rectal laxatives) and the possibility of using a rectal probe.

Data were prospectively collected and included patient demographics, main indication for TAI (constipation or FI), type of FI (active, passive, or mixed), type of constipation (slow transit constipation or obstructed defecation disorder) based on Rome criteria[8], and the etiology of the constipation or FI. We also interviewed each patient using a validated FI score (Cleveland Clinic Incontinence Score, CCIS 0-20)[9], a constipation severity score (Kess score, 0-39)[10], or an NBD score (NBD, 0-47)[11], as appropriate. Because of the heterogeneity of the population (patients with constipation or FI), each patient was classified as having a severe defecation disorder based on the severity score of their main symptom (Kess score > 20 if constipation was the main symptom[10], CCIS > 10 if FI was the main symptom[12], or NBD score > 14 for a neurological disease[11]). The evaluation of the patients prior to the treatment was conducted based on their heterogeneous background pathologies. However, for most patients, the evaluation included anorectal physiology tests, defecography, and a colonic transit time study performed as previously described[13-15]. Anal manometry was performed using a water-perfused system. Maximal anal resting and squeeze pressures were recorded. Rectal sensation to balloon distension with air was assessed. The smallest amount of distension felt by the patient (the threshold of conscious rectal sensation) and the maximum tolerable volume were determined[14].

The Peristeen® irrigation system was used[6]. Patients were prepared using information leaflets, DVDs, and meetings with specialist nurses where the system was presented and explained (training session). TAI attempts were performed under the supervision of specialist nurses using a previously described procedure[6]. The modalities of the TAI training session were evaluated with respect to the volume of water used for the irrigation and the number of pressings necessary to inflate the balloon. The nurses evaluated the progress of the training sessions and reported any difficulties (expulsion of catheter, fluid leakage, no evacuation of stools during irrigation). During the first month following the training sessions, the patients were asked to perform washouts daily or every two days. Appointments were scheduled for 1, 3, 6, and 12 mo after the training sessions to discuss the various treatment modalities (frequency of enema administration, volume of water used, etc.). The patients were encouraged to contact the specialist nurses in the event of problems.

We assessed the outcomes based on compliance with TAI one year after the training sessions. To identify TAI users one year later, we mailed a questionnaire to patients who were introduced to TAI from January 2010 to December 2014 and who were not seen at the 12-mo follow-up. The patients were asked if they were still using the TAI system, how they used it, and whether they had experienced any technical problems or complications. If they were no longer using TAI, they were asked to explain why they had stopped and when.

The proportion of patients in each outcome was expressed in terms of intention-to-treat (ITT). The ITT approach was designed to analyze the patients who had attended a TAI training session, including those who had failed the first session and those who were lost at follow-up. The purpose was to assess the outcomes of the entire cohort of patients who had been recruited for the TAI treatment.

To analyze the predictive factors of the outcomes of TAI, the patients were divided into two groups based on their compliance with TAI one year after their training session. They were classified as non-adopters if they stopped using TAI within one year of the start date or as adopters if they had continued the therapy. Patients who were lost at follow-up or who failed the training session were not included in the analysis of predictive factors.

The χ2 test was used to compare qualitative variables. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare quantitative variables. A multivariate analysis was performed to identify relationships between disease background factors and the outcome of TAI. Variables with a P < 0.15 in the univariate analysis were used for the stepwise logistic regression. Results are expressed as odds ratios and 95%CI. Data are expressed as medians or mean values with a range or standard deviation. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

One hundred eight patients with defecation disturbances [87 women and 21 men; median age 55 years (range 18-83)] over a four-year period were introduced to TAI at our institution. TAI was used to treat isolated constipation in 51 patients, relieve constipation associated with retentive FI in 47, and treat isolated FI in 10. The main complaints, type of constipation and FI, main causes, and prior surgical procedures for defecation disorders are given in Table 1.

| Study group (n = 108) | |

| Predominant symptoms | |

| Constipation | 65 (60.2) |

| Fecal incontinence | 43 (39.8) |

| Type of constipation | |

| Slow transit constipation | 15 (15.3) |

| Obstructed defecation | 47 (48) |

| Mixed constipation | 36 (36.7) |

| Type of FI | |

| Active FI | 12 (21) |

| Passive FI | 42 (73.7) |

| Mixed FI | 3 (5.3) |

| Main causes of constipation/FI | |

| Neurological disease (multiple sclerosis, spina bifida, spinal cord injury, Parkinson disease): | 41 (38) |

| Slow transit constipation | 17 (15.7) |

| Obstructed defecation syndrome | 28 (25.9) |

| FI | 22 (20.4) |

| Pudendal neuropathy | 11 |

| Sphincter lesion | 5 |

| Low rectal/reservoir compliance | 5 |

| Idiopathic | 1 |

| Prior surgical procedures | 32 (29.6) |

| Rectal resection with colo-anal anastomosis | 3 |

| Colonic resection with colo-rectal anastomosis | 3 |

| Colonic resection with ileo-rectal anastomosis | 1 |

| Hysterectomy | 1 |

| Cystopexy | 2 |

| Rectopexy | 4 |

| Starr | 1 |

| Sacral nerve stimulation | 15 |

| Anorectal malformation | 1 |

| Rectoplasty | 1 |

The study protocol complied with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki (6th revision, 2008) as reflected in a priori approval by the institution’s human research committee (N°E2016-64).

Five patients (4.6%) withdrew during the first training session, 4 because of repeated expulsion of the rectal catheter during irrigation and water leakage around the rectal catheter, and 1 because of difficulty emptying the instilled water. Nine patients (8.3%) needed more than one training session (2 sessions for 8 patients and 3 sessions for 1 patient) because they did not feel comfortable performing the TAI after one session. Following a satisfactory home-use training session, 92 patients (85.2%) were able to auto-administer TAI, while 11 patients (10.2%) required assistance either from a nurse (7) or a member of the family (4). Seventy percent of the patients performed TAI at least 2 to 3 times a week.

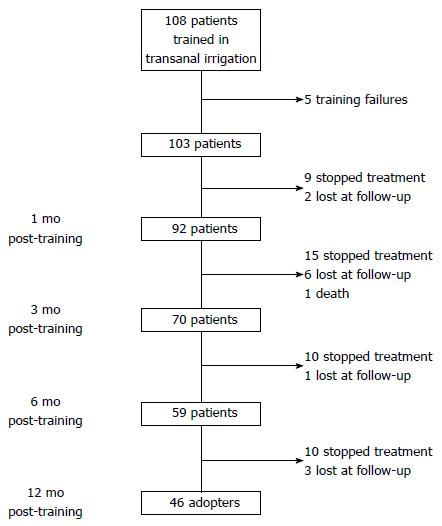

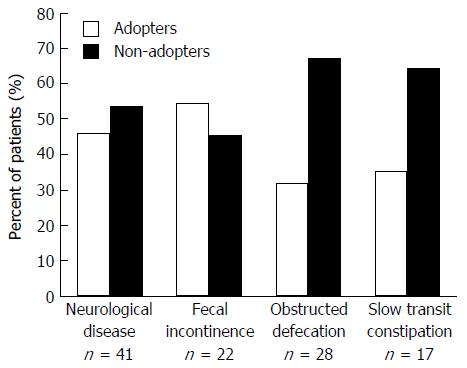

The outcomes of the patients based on compliance with TAI one year after the training session are summarized in a flow diagram (Figure 1). At the one-year follow-up, 46 of the 108 patients still maintained TAI at home and were considered as adopters (ITT 42.6%) while 62 had discontinued TAI and were considered as non-adopters (ITT 57.4%), including 44 who had discontinued TAI prior to the one-year follow-up, 5 who had failed during the first training session, 12 who were lost at follow-up, and 1 who died for a reason unrelated to TAI. The successful outcomes with TAI (ITT analysis) are presented in Figure 2 based on the etiology of the defecation disorder. The median follow-up after the successful start of TAI was 16 (1-67) mo.

The main reasons for discontinuing TAI following a successful training session were technical problems (catheter expulsion, rectal balloon bursting, instilled water leakage or retention, pain during irrigation, anal bleeding, anal fissure) (16 patients, 36.4%), inefficacy (18 patients, 40.9%), and too many constraints (10 patients, 22.7%). Constraints were mainly related to the time spent performing the irrigation. The median time the patients used TAI before discontinuing was 3 mo (range, 0.2-11). At the last follow-up, the discontinuation of TAI had led to the resumption of a medical treatment for 21 patients (42.8%) and an invasive surgical procedure for 18 (36.7%): Malone antegrade continence enema, n = 6; sigmoid colostomy, n = 4; ileostomy, n = 1; coloproctectomy, n = 1; rectopexy, n = 2; sacral nerve stimulation, n = 3; and artificial bowel sphincter, n = 1. Eight patients preferred resuming traditional water or sodium phosphate enemas.

Of the 46 adopters, 13 (28.3%) complained of the time spent on bowel management while 25 (54.3%) reported 47 minor and self-limiting adverse events. The most common events reported were leakage of irrigation fluid around the catheter (16 events, 34%), pain on catheter insertion or water instillation (14 events, 29.9%), catheter expulsion (9 events, 19.1%), rectal balloon bursting (5 events, 10.6%), and instilled water retention (3 events, 6.4%). No cases of bowel perforation were reported at follow-up.

To identify predictive factors of compliance with TAI, we compared the characteristics of the 44 non-adopters who had discontinued TAI during the first year (excluding patients who were lost at follow-up or who had failed the training session) with those of the 46 adopters.

Predictive factors based on baseline assessments: We did not find any significant differences between adopters and non-adopters related to age, gender, body mass index, main symptom (constipation or FI), severity of main symptom based on severity scores, type of constipation or FI, underlying pathology, or previous colo-rectal surgeries (Table 2). The anorectal physiological parameters, colonic transit times, and defecography results of the adopters and non-adopters were similar (Table 2).

| Variables | Adopters | Non-adopters | P value |

| n = 46 | n = 44 | ||

| Age (yr) | 55.9 ± 13.9 | 51 ± 17.8 | 0.29 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 36 (78) | 38 (86) | 0.46 |

| Male | 10 (22) | 6 (14) | |

| BMI | 25.4 ± 4.3 | 23.6 ± 4.9 | 0.05 |

| Main symptom | |||

| Constipation | 22 (48) | 28 (64) | 0.19 |

| FI | 24 (52) | 16 (36) | |

| Type of constipation | n = 42 | n = 39 | |

| Slow transit | 8 (19) | 6 (15.4) | 0.48 |

| Obstructed defecation | 17 (40.5) | 21 (53.8) | |

| Mixed | 17 (40.5) | 12 (30.8) | |

| Type of FI | n = 28 | n = 24 | 0.82 |

| Urge | 7 (25) | 5 (21) | |

| Passive | 19 (68) | 18 (75) | |

| Mixed | 2 (7) | 1 (4) | |

| Main causes of constipation/FI | |||

| Neurological disease | 19 (41.3) | 14 (31.8) | 0.47 |

| Slow transit constipation | 6 (13) | 8 (18.2) | 0.70 |

| Obstructed defaecation syndrome | 8 (17.4) | 11 (25) | 0.53 |

| FI | 13 (28.3) | 11 (25) | 0.91 |

| Prior surgical procedures | 11 (24) | 17 (39) | 0.13 |

| n = 42 | n = 40 | ||

| Severe defecation disorders according to severity scores | 32 (76) | 31 (77) | 0.99 |

| Anorectal manometry: | n = 38 | n = 33 | |

| Resting pressure (cmH2O) | 66.6 ± 30.7 | 57.2 ± 27.3 | 0.20 |

| Squeeze pressure (cmH2O) | 57.8 ± 56.5 | 59.6 ± 67.7 | 0.81 |

| Threshold volume (mL) | 21.9 ± 15.7 | 15.7 ± 6.9 | 0.16 |

| Maximum tolerated volume (mL) | 225.1 ± 98.6 | 234.5 ± 145.6 | 0.83 |

| Rectal compliance (mL/cmH2O) | 4.1 ± 2.4 | 4.2 ± 4 | 0.51 |

| Colonic transit time | n = 31 | n = 33 | |

| Right colon (h) | 28.1 ± 19.7 | 29.9 ± 18.4 | 0.54 |

| Left colon (h) | 35.5 ± 23.6 | 38 ± 25.4 | 0.60 |

| Recto-sigmoid colon (h) | 23.6 ± 21.8 | 29 ± 26.6 | 0.53 |

| Total (h) | 90.2 ± 35.4 | 88.4 ± 44.3 | 0.97 |

| Defecography | |||

| Rectal prolapse | n = 29 | n = 22 | |

| or recto-anal procidentia | 9 (31) | 6 (27) | 0.22 |

Predictive factors based on TAI modalities: Only the satisfactory progress of the first training session was related to the outcome of TAI. Non-adopters were more likely to experience a first training session complicated by technical problems (expulsion of catheter, fluid leakage, or no evacuation of stools during irrigation) than adopters (P = 0.02) (Table 3). The multivariate analysis confirmed that the success of the first training session was the only predictive factor of mid-term compliance with TAI (odds ratio = 4.9, 1.3-18.9; P = 0.02). The number of sessions required to learn the TAI technique, the type of administration (self-administered or assisted), the frequency of use of the TAI system, and the number of side-effects observed during TAI were not predictive factors of discontinuation (Table 3).

| Variables | Adopters | Non-adopters | P value |

| n = 46 | n = 44 | ||

| Training sessions | |||

| Number of training sessions | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 1 | 0.30 |

| Volume of instilled water | 607.9 ± 214.8 | 517.4 ± 241.7 | 0.07 |

| Numbers of balloon pressings | 3.2 ± 1.3 | 3.2 ± 1.8 | 0.55 |

| Auto-administration | 40 (87) | 42 (95.5) | 0.30 |

| Assisted administration | 6 (13) | 2 (4.5) | |

| Complicated first training session | 4 (9) | 13 (29) | 0.02 |

| Current sessions | n = 45 | n = 24 | |

| Frequency of irrigation: | |||

| 2-3/wk or more | 35 (78) | 22 (92) | 0.35 |

| Less than 2-3 wk | 10 (22) | 2 (8) | |

| Total number of side-effects | 1.04 ± 1.2 | 1.1 ± 1 | 0.51 |

| Percent of patients: | |||

| with side-effects | 25 (54) | 29 (66) | 0.37 |

| with constraints | 13 (28) | 16 (36) |

Our main aim was to investigate compliance with TAI by adults with constipation or FI one year after a TAI training session. Based on ITT, 43% of the 108 patients were still using TAI one year after their training session. The patients with FI had the best results, with 54.5% remaining compliant with TAI. Only one-third of the patients who complained of slow transit constipation or obstructed defecation syndrome continued TAI.

Studies on adults with defecation disorders of mixed etiology have reported variable response rates to TAI[5]. The proportion of patients with a positive outcome with TAI ranges from 30%[16] to 78%[17]. The large difference in reported response rates may be due to three main inherent factors of the study designs: (1) the success criteria; (2) the TAI system and training modalities; and (3) the duration of the follow-up. Nevertheless, the results of the present study were relatively consistent with those of a previous study by Christensen et al[6], who used similar success criteria. In the study by Christensen et al[6], patients still using TAI at follow-up, patients in whom symptoms had resolved during treatment and thus no longer needed the treatment, and patients whose bowel symptoms had been successfully treated but who had died for reasons not related to treatment were regarded as having a successful TAI outcome. They reported a success rate of 47% for the entire cohort, 51% for patients with FI, and 34% for patients with slow transit constipation or obstructive defecation syndrome[6]. They also reported that TAI was successful in 63% of patients with a neurological disorder, which is at odds with our results showing that only 46% of such patients were compliant with TAI at the one-year follow-up[6]. This inconsistency may be due to different treatment durations. Indeed, Christensen et al[6] determined the success of TAI at the last follow-up (ranging from 1 to 116 mo). However a high drop-out rate over time is common in patients with a neurological disorder. For example, only 35% of such patients continue TAI for 3 years[7]. These discrepancies indicate that it is important to evaluate all patients over the same time frame. We decided to use a one-year follow-up assessment since (1) the risk of underestimating the percentage of non-compliant patients is limited given that most dropouts occur at the beginning of the treatment[6]; and since (2) few patients are lost at follow-up.

We confirmed that FI patients are relatively good candidates for TAI, with 54.5% remaining compliant one year after the training session despite the constraints and technical problems, which is in agreement with previous studies[6,18,19]. This suggested that patients are willing to suffer the side-effects because some of their colorectal dysfunctions are resolved. While the results of ITT FI by sacral nerve stimulation, for example, have been reported to be slightly better one year after implantation (66% ITT)[20], TAI requires no surgical intervention and has minimal side effects. TAI may thus be suitable as a second-line treatment for incontinent patients, especially those with retentive FI.

In the present study, like others[6,18], we observed an overall discontinuation rate of 57%. The most common reason for discontinuing TAI was the lack of efficacy (41%). However, 59% discontinued because of technical problems or constraints. Regardless of the reason, discontinuation could lead to a delay in the effective management of defecation disorders and a decrease in the cost-effectiveness of TAI. We thus focused our patient selection efforts in order to identify predictive factors of non-compliance. In previous studies, several predictive factors of non-compliance have been suggested, including gender, mixed constipation and FI symptoms, prolonged colonic transit time in patients with NBD[7], anal insufficiency, and low rectal volume in a population with defecation disorders of different origins[6]. However, no consistent, reliable patterns indicating a greater risk of discontinuing TAI have been identified. In the present study, technical problems that occurred during the first training session were the only predictive factor for TAI discontinuation. Patients who experienced moderate technical problems during the training session that were not sufficient to discontinue the treatment after the session were five times more likely to be non-adopters because of the inefficacy of TAI or persistent technical problems. No other studies have investigated the modalities of training sessions as predictive factors of a successful outcome. If our results are confirmed with a larger patient cohort, this could help optimize the management of these patients by, for example, using more training sessions with specialized nurses in a clinical or home setting in the early treatment phase.

The present study had several main limitations. First, it was a retrospective study. Second, several sub-groups of patients were required to identify predictive factors of non-compliance due to the heterogeneity of the population. As such, our population may have been underpowered for such an analysis. Third, we did not use the symptom severity scores to evaluate TAI efficacy. However, the poor correlation between the subjective perception of patients of their functional bowel disorders and the symptom severity scores is well known[21]. Consequently, the continuation of a binding treatment such as TAI by patients for at least 1 year appeared to us to be as clinically relevant as severity scores in reaching the conclusion that TAI provides a significant clinical benefit to patients.

With the exception of progress during the first training session, no predictive factors for compliance with TAI were identified. This suggested that the first training session should be better structured in order to promote more realistic expectations about treatment efficacy, side-effects and, especially, constraints in order to reduce the discontinuation rate.

The authors would like to thank Gene Bourgeau, MSc, CT, for proofreading the manuscript.

Transanal irrigation (TAI) is an interesting therapeutic option for defecation disorders that are refractory to first-line medical treatments. However, mid- and long-term compliance with TAI is disappointing. The main reasons and the predictive factors of compliance with TAI in adults have been poorly described to date.

A better understanding of why many patients with defecation disorders who are treated with TAI discontinue the therapy after the training session should help reduce the rate of failure.

Like others, the authors found that less than 50% of the trained patients continued to use TAI one year after their training session. They failed to identify any consistent, reliable patterns indicating a greater risk of discontinuing TAI. However, we showed for the first time that (1) 59% of the patients who reported discontinuing TAI gave reasons independent of the efficacy of the treatment (technical problems or constraints) and that (2) the only predictive factor for TAI discontinuation was the progress of the training.

Presented results indicated that the first training session should be better structured in order to promote more realistic expectations of treatment efficacy, side-effects, and, especially, constraints in order to reduce the discontinuation rate. In the future, authors plan to schedule several successive hospital or home training sessions with a specialized nurse for patients whose first session led to complications in order to improve their compliance.

The first training session is important to predict patient compliance with TAI.

This paper on TAI is interesting, well written, with exhaustive tables and figures. The limitations are already outlined by the authors at the end of the discussion section.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: France

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Santoro GA, Garcia-Olmo D S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Coggrave M, Norton C, Cody JD. Management of faecal incontinence and constipation in adults with central neurological diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD002115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Heidelbaugh JJ, Stelwagon M, Miller SA, Shea EP, Chey WD. The spectrum of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: US survey assessing symptoms, care seeking, and disease burden. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:580-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shandling B, Gilmour RF. The enema continence catheter in spina bifida: successful bowel management. J Pediatr Surg. 1987;22:271-273. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Christensen P, Krogh K. Transanal irrigation for disordered defecation: a systematic review. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:517-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Emmett CD, Close HJ, Yiannakou Y, Mason JM. Trans-anal irrigation therapy to treat adult chronic functional constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Christensen P, Krogh K, Buntzen S, Payandeh F, Laurberg S. Long-term outcome and safety of transanal irrigation for constipation and fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:286-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Faaborg PM, Christensen P, Kvitsau B, Buntzen S, Laurberg S, Krogh K. Long-term outcome and safety of transanal colonic irrigation for neurogenic bowel dysfunction. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:545-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Irvine EJ, Müller-Lissner SA. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. 1999;45 Suppl 2:II43-II47. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:77-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2089] [Cited by in RCA: 1967] [Article Influence: 61.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Knowles CH, Eccersley AJ, Scott SM, Walker SM, Reeves B, Lunniss PJ. Linear discriminant analysis of symptoms in patients with chronic constipation: validation of a new scoring system (KESS). Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1419-1426. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Krogh K, Christensen P, Sabroe S, Laurberg S. Neurogenic bowel dysfunction score. Spinal Cord. 2006;44:625-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Damon H, Guye O, Seigneurin A, Long F, Sonko A, Faucheron JL, Grandjean JP, Mellier G, Valancogne G, Fayard MO. Prevalence of anal incontinence in adults and impact on quality-of-life. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30:37-43. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Bouchoucha M, Devroede G, Arhan P, Strom B, Weber J, Cugnenc PH, Denis P, Barbier JP. What is the meaning of colorectal transit time measurement? Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:773-782. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Gourcerol G, Gallas S, Michot F, Denis P, Leroi AM. Sacral nerve stimulation in fecal incontinence: are there factors associated with success? Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:3-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Melchior C, Bridoux V, Touchais O, Savoye-Collet C, Leroi AM. MRI defaecography in patients with faecal incontinence. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:O62-O69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Koch SM, Melenhorst J, van Gemert WG, Baeten CG. Prospective study of colonic irrigation for the treatment of defaecation disorders. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1273-1279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chan DS, Saklani A, Shah PR, Lewis M, Haray PN. Rectal irrigation: a useful tool in the armamentarium for functional bowel disorders. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:748-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gosselink MP, Darby M, Zimmerman DD, Smits AA, van Kessel I, Hop WC, Briel JW, Schouten WR. Long-term follow-up of retrograde colonic irrigation for defaecation disturbances. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:65-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cazemier M, Felt-Bersma RJ, Mulder CJ. Anal plugs and retrograde colonic irrigation are helpful in fecal incontinence or constipation. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3101-3105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wexner SD, Coller JA, Devroede G, Hull T, McCallum R, Chan M, Ayscue JM, Shobeiri AS, Margolin D, England M. Sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence: results of a 120-patient prospective multicenter study. Ann Surg. 2010;251:441-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Drossman DA, Chang L, Bellamy N, Gallo-Torres HE, Lembo A, Mearin F, Norton NJ, Whorwell P. Severity in irritable bowel syndrome: a Rome Foundation Working Team report. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1749-1759; quiz 1760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |