Published online Feb 21, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i7.2366

Peer-review started: September 17, 2015

First decision: October 14, 2015

Revised: November 3, 2015

Accepted: December 8, 2015

Article in press: December 8, 2015

Published online: February 21, 2016

Processing time: 136 Days and 1.7 Hours

AIM: To investigate the combined antegrade-retrograde endoscopic rendezvous technique for complete oesophageal obstruction and the swallowing outcome.

METHODS: This single-centre case series includes consecutive patients who were unable to swallow due to complete oesophageal obstruction and underwent combined antegrade-retrograde endoscopic dilation (CARD) within the last 10 years. The patients’ demographic characteristics, clinical parameters, endoscopic therapy, adverse events, and outcomes were obtained retrospectively. Technical success was defined as effective restoration of oesophageal patency. Swallowing success was defined as either percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG)-tube independency and/or relevant improvement of oral food intake, as assessed by the functional oral intake scale (FOIS) (≥ level 3).

RESULTS: The cohort consisted of six patients [five males; mean age 71 years (range, 54-74)]. All but one patient had undergone radiotherapy for head and neck or oesophageal cancer. Technical success was achieved in five out of six patients. After discharge, repeated dilations were performed in all five patients. During follow-up (median 27 mo, range, 2-115), three patients remained PEG-tube dependent. Three of four patients achieved relevant improvement of swallowing (two patients: FOIS 6, one patient: FOIS 7). One patient developed mediastinal emphysema following CARD, without a need for surgery.

CONCLUSION: The CARD technique is safe and a viable alternative to high-risk blind antegrade dilation in patients with complete proximal oesophageal obstruction. Although only half of the patients remained PEG-tube independent, the majority improved their ability to swallow.

Core tip: Complete obstruction in the proximal oesophagus is rare after radiotherapy for head and neck cancers. We present our institutional experience with endoscopic rendezvous dilation and the clinical outcomes. This technique offers a safe and viable alternative to high-risk blind antegrade dilation. In our series, the rate of technical success was high. Although half of the patients remained percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy-tube dependent, the majority showed relevant improvement in their ability to swallow and, consequently, in their quality of life.

- Citation: Bertolini R, Meyenberger C, Putora PM, Albrecht F, Broglie MA, Stoeckli SJ, Sulz MC. Endoscopic dilation of complete oesophageal obstructions with a combined antegrade-retrograde rendezvous technique. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(7): 2366-2372

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i7/2366.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i7.2366

Complete obstruction in the proximal oesophagus is a rare but severe complication after radiotherapy in head and neck cancer patients[1-3]. Less common causes are gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, Plummer-Vinson-Syndrome, or caustic injury[4-7]. Antegrade reopening and dilation of a complete oesophageal obstruction is difficult and carries a high risk of oesophageal perforation. A combined antegrade-retrograde endoscopic rendezvous procedure offers better visualisation and safer dilation. The antegrade-retrograde rendezvous technique was first described by van Twisk et al[8] in 1998, followed by Bueno in 2001[9]. This technique is also termed combined antegrade-retrograde endoscopic dilation (CARD). Several other small series[10-14] were subsequently reported. Most series reported on the technical feasibility of the procedure, but rarely on the functional assessment of swallowing. Therefore, our primary aim was to describe the swallowing outcome, including the dependency on a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG)-tube, using the objective functional oral intake scale (FOIS) to assess patients undergoing this rare endoscopic treatment.

This single-centre case series included a consecutive cohort of patients who underwent CARD for complete obstruction in the area of the pharyngoesophageal segment at the Cantonal Hospital, St. Gallen, Switzerland, between July 2005 and February 2015. Prior to the intervention, all patients were completely unable to swallow and PEG-tube dependent. The diagnosis of complete obstruction was confirmed by endoscopic and/or radiologic findings. Data extracted included demographic characteristics, clinical parameters, endoscopic therapy, adverse events, and outcome. Approval for using pseudoanonymized patient data was obtained from the local ethics committee and all study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

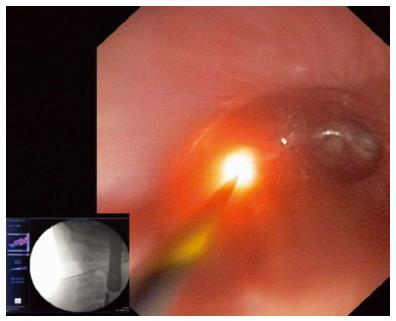

The procedures were performed jointly by experienced endoscopists and head and neck surgeons with the patient under general anaesthesia. The existing PEG-tube gastrostomy is a condition to get access to the stomach for the retrograde part of this rendezvous procedure. The first step was to remove the PEG-tube carefully and to keep access to the stomach with a guidewire through the gastrostomy. Then, dilation of the gastrostomy with Savary bougies (Cook Medical, United Kingdom) up to 12 mm over the guidewire was necessary to pass the endoscope. In our experience, balloon dilation was not effective. All retrograde endoscopies were performed with extra-slim nasal endoscopes (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) (Figure 1). Antegrade endoscopy was performed transorally with rigid and/or flexible endoscopes (left to the discretion of the head and neck surgeon). The obstruction within the oesophagus was identified with both endoscopes (Figure 2). Fluoroscopy on the one hand and antegrade transillumination on the other hand are important tools to guide the retrograde and the antegrade endoscope towards each other. Fluoroscopy helps to estimate the length of the obstructed oesophagus and the direction of both endoscopes. Furthermore, the retrograde puncture of the complete obstruction was directed by transillumination (Figure 3). It was crucial to use the hard end of the wire, as it is impossible to succeed puncture of the completely obstructed oesophagus with the soft tip of the wire. The puncture procedure was documented by endoscopy and fluoroscopy (Figure 3). After successful puncture the wire was passed through the obstruction and finally picked up by the operator performing the antegrade endoscopy. Then, dilation was started using small Savary bougies (Cook Medical, United Kingdom) from the antegrade site, followed by insertion of a nasogastric tube to maintain the patency and balloon dilations (Figure 4). Nasogastric tubes were re-inserted after subsequent dilations until the dilated oesophageal lumen was large enough, according to the discretion of the operators. After the procedure a new PEG-tube was placed percutaneously to provide additional nutritional support. Video 1 summarizes the single steps of the procedure. The details of the procedure were not based on a strict protocol. The endoscopists were allowed to choose any available endoscopic device to succeed.

Technical success was defined as effective restoration of oesophageal patency. The swallowing success was defined as either PEG-tube independency and/or relevant improvement of oral food intake, as assessed by the FOIS, a 7-point ordinal scale documenting the functional level of oral intake of food and liquids[15]. The scale focuses on the patient’s intake by mouth on a daily basis (Table 1). Though the pre-therapeutic FOIS level was not assessed formally, the score of all patients corresponded to a FOIS level 1 (nothing by mouth, PEG-tube dependent) as they were unable to swallow anything due to complete obstruction. Relevant improvement of swallowing (FOIS ≥ level 3) at the time of follow-up was defined as swallowing success.

| Level 1 | Nothing by mouth |

| Level 2 | Tube dependent with minimal attempts of food or liquid |

| Level 3 | Tube dependent with consistent oral intake of food or liquid |

| Level 4 | Total oral diet of a single consistency |

| Level 5 | Total oral diet with multiple consistencies, but requiring special preparation or compensations |

| Level 6 | Total oral diet with multiple consistencies without special preparation, but with specific food limitations |

| Level 7 | Total oral diet with no restrictions |

The cohort consisted of six patients [five males; mean age 71 years (range, 54-74)]. Patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 2. Two patients died due to their underlying tumour disease 4 and 20 mo after the endoscopic rendezvous intervention. Death was associated with cancer.

| No | Sex | Age | Diagnosis | Prior radiotherapy (max dose i. Gy) | Surgery | Chemotherapy | Technical success | FOIS | Notes |

| 1 | F | 68 | Hypopharyngeal carcinoma T3 N0 and oropharyngeal carcinoma T2 N0 | 68 | No | Yes | Yes | 6 | |

| 2 | M | 59 | Complete occlusion of sinus piriformis after Lyell syndrome | No | No | No | Yes | 6 | |

| 3 | M | 54 | Squamous carcinoma of the cervical oesophagus cT3 cN2 cM0 | 66 | No | Yes | No | - | Died before follow-up with PEG-tube |

| 4 | M | 74 | Proximal oesophageal carcinoma and carcinoma of the glottic larynx cT2 cN0 | Glottis: 66 Oesophagus: 68 | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | Died before follow-up with PEG-tube |

| 5 | M | 68 | Carcinoma of the hypopharynx | 70 | Yes | No | Yes | 2 | |

| initial cT2c No cM0 | |||||||||

| 6 | M | 71 | Carcinoma of the larynx cT3 cN2 | 68 | No | No | Yes | 7 |

Technical details concerning the endoscopic rendezvous intervention are summarized in Table 3. Rigid endoscopes were used in four of six patients by head and neck surgeons; while flexible instruments were applied in two patients for the antegrade access. The retrograde puncture of the obstruction was achieved with a VisiGlide guidewire (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) in four of six cases (Figure 3). In each case, once a lumen was established, a wire was cautiously passed through, and dilation (median 10 mm, range, 6 - 10 mm) was performed with Savary bougies (Cook Medical, United Kingdom). After the first intervention, nasogastric tubes were inserted in all cases to keep the dilated obstruction open and a new PEG-tube was placed successfully in all patients.

| Type of antegrade endoscope | |

| Rigid, flexible | 4, 2 |

| Method of retrograde puncture of the obstruction | |

| VisiGlide guidewire | 4/6 |

| Argon beamer | 1/6 |

| First stricture dilation | |

| With Savary bougie | 5/5 |

| Size | median 10 mm (range 6 - 10 mm) |

| Subsequent dilations before discharge | |

| With balloon | 3/5 patients |

| size range | 15-16.5 mm |

| With bougie | 2/5 patients |

| size range | 12-15 mm |

| Success rate of rendezvous procedures | |

| Technical success | 5/6 (83%) |

| Need for recurrent dilations after discharge | 5/5 |

| Swallowing success | |

| Time of follow-up, median (range) | 27 mo (2-115) |

| Need for long-term PEG-tube | 3/6 |

| Functional oral intake | |

| Tube dependent with minimal attempts of food or liquid (level 2) | 1 |

| Total oral diet with multiple consistencies without special preparation, but with specific food limitations (level 6) | 2 |

| Total oral diet with no restrictions (level 7) | 1 |

| Complications of rendezvous procedures | |

| Mediastinal emphysema (no surgery needed) | 1/6 |

| Death | 0/6 |

Technical success: Technical success was achieved in five out of six patients (Tables 2 and 3). In one patient with squamous carcinoma of the proximal oesophagus, the complete obstruction in the proximal oesophagus could not be punctured retrogradely by VisiGlide wire, super stiff wire, Savary wire, or argon beamer. All five patients with successful puncture were treated with Savary bougies [median size of first dilation 10 mm (range, 6-10 mm)]. However, all five patients with technical success needed subsequent dilations; three were treated with balloons (size range, 15-16.5 mm; Figure 4) and the other two patients with bougies (size range, 12-15 mm) (Table 3). After discharge, repeated dilations or stenting were performed in all five patients during long-term follow-up; however the number of interventions and the time interval varied significantly between the individual patients, depending on their symptoms.

Swallowing success: At the date of follow-up (median 27 mo, range, 2-115 mo), the FOIS results of all patients who survived were available (Table 3). Before the procedure, all patients were completely unable to swallow correlating with FOIS level 1: Nothing by mouth, dependent from PEG-tube feeding. After the endoscopic treatment, containing the initial rendezvous procedure and the following dilations, in three patients clinical success with a FOIS score more than 6 was reached. Unfortunately, two patients died before the authors could draw any conclusion regarding swallowing during the follow up. One patient had a poor result with a FOIS level of 2 and did not reach swallowing success (defined as FOIS ≥ 3).

Adverse events: One patient developed a mediastinal emphysema following CARD, without a need for surgery. There were no deaths associated with the endoscopic procedure (Table 3).

We present a retrospective single-centre case series of all patients over the last 10 years who were treated with endoscopic antegrade-retrograde rendezvous dilation for complete obstruction in the proximal oesophagus or hypopharynx. The majority of patients had undergone previous radiotherapy, for treatment of head and neck and proximal oesophagus cancers, which is a major cause of stricture or obstruction in the proximal oesophagus[1-3]. Pharyngoesophageal stricture or stenosis necessitating dilations have been described in up to one fifth of patients after radio(chemo)therapy for head and neck cancer[16,17]. A correlation has been described between radiation stricture induction and radiation dose, as well as volume of irradiation to organs at risk (e.g., upper oesophagus)[18]. Complete obstruction may also occur in a minority of affected patients[2].

While intensity modulated radiotherapy better spares the parotid gland and reduces xerostomia rates[19], a review of published literature suggested there is a higher rate of oesophageal stricture with this treatment compared with 3D conventional radiotherapy[20]. Chen et al[21] demonstrated that when planning target volumes were reduced (from 5 to 3 mm) and there was daily imaging of the application of radiotherapy treatment, the rate of radiation-induced oesophageal stricture was reduced from 14% to 7%. There is currently a stronger focus on sparing the dose to the pharyngeal constrictor muscles and the cervical oesophagus when feasible; thus, lower rates of (pharyngo-) oesophageal stricture might be expected in the future as a side-effect of radiotherapy.

This is one of the first series presenting clinical outcome data based on assessment of the patients’ oral ingestion ability after rendezvous treatment using a validated score. Grooteman et al[22] used the Dakkak and Bennett score. Goguen et al[23] reported the outcome in terms of the achieved diet and the PEG-tube dependency, and the clinical outcome was recorded by the swallow therapists. The limited data on this topic illustrate that professional medical teams who take care of patients suffering from dysphagia after head and neck surgery or radiotherapy in the head and neck region (e.g., speech therapists, head and neck surgeons, medical radio-oncologists, and gastroenterologists) rarely assess and publish the patients’ functional oral food intake using objective scores of their daily routine. In our study, the patients’ abilities to intake food orally were assessed using the FOIS. This tool was initially designed to document changes in functional oral intake of food and liquid in stroke patients[15]. The scale is useful to document a clinical change, for example before and after an intervention, such as with speech therapy[15,24].

Other scales are available, such as the Mann Assessment of Swallowing Ability, Acute Stroke Dysphagia Screen, and the Dysphagia Outcome and Severity Scale. However, they are often disease-specific. The FOIS offers an easy and quick assessment to reflect the individual patient’s situation in daily life and to document a clinical change. The FOIS can be easily used by physicians and other professional health workers who are not experienced in adult dysphagia management. However, although FOIS is a useful tool to document oral intake, it is also important to pay attention to other characteristics, such as quality of life and nutritional status.

Although only half of our patients remained PEG-tube independent, the majority (three of four patients) had relevant improvement of swallowing (FOIS ≥ level 3) and, therefore, gained quality of life. The largest case series to date[22] reported that 44% of the patients were able to eat at least soft food; whereas, 56% of their patients needed permanent PEG-tube feeding after a median follow-up of 1.8 years. Other authors reported a clinical success rate without PEG-tube dependency between 30% and 60%[13,23,25,26]. Previous reports found oral intake was possible in 45%-80% of subjects after these procedures[22,23,25,26]. Grooteman et al[22] reported that only 24% of the patients were dysphagia-free. We did not investigate dysphagia; rather, we evaluated the diet that was possible during follow-up as this is easy for patients to report on. The findings in literature concerning the dependency on PEG-tube feeding and oral intake are similar to our study.

The most difficult part of the antegrade-retrograde rendezvous procedure is to gain access through the completely obstructed oesophagus. Our data regarding technical success (five of six patients) are in line with the findings of other studies, which reported technical success rates of 83%-100%[13,23,25,26], demonstrating that this procedure is technically feasible. In our series, we started all punctures with guide wires (0.035 inch). It is crucial to puncture with the hard end of the wire, as it is impossible to succeed puncture of a complete oesophageal obstruction with the soft tip of the wire. Furthermore, it is important to reach a good transillumination from the antegradely inserted laryngoscope. The combination of an adequate transillumination and fluoroscopy helps the two operators to bring the two endoscopes as near as possible and to have the best condition to puncture into the complete obstruction. The endoscopist has to be patient. One can try also other wires as super stiff or Savary wires. One of our cases was a technical failure, after trying to puncture with a super stiff wire, a Savary wire, and argon beamer. In most series[9,13,14,22,26], guidewires were also used. Grooteman et al[22] also used electrocautery. Other devices utilized were biopsy forceps[27], needle knifes (e.g., biliary needle knifes)[11,22], and needles, e.g., used in endoscopic ultrasound for fine-needle aspiration[11,14,27]. Schembre et al[14] mentioned severe complications, such as abscesses, after using needles and concluded that operators should be very cautious. In a single case, we utilized argon beamer coagulation in addition to the wire and succeeded. Overall, we think that the operator should be aware of the armamentarium of various devices for puncture and should feel confident with the tools utilized.

In our case series, a single case of mediastinal emphysema occurred as a complication of the rendezvous procedure. Fortunately, no surgery was needed. Goguen et al[23] reported pneumomediastinum in 18% of subjects, but also oesophageal perforation in 5% and gastrostomy tube site problems in 16% (e.g., leakage by pulling the stomach away from abdominal wall). We only used thin nasal gastroscopes that may have prevented local complications at the gastrostomy tube site; whereas, Goguen et al[23] used adult endoscopes. Dellon et al[26] also described an oesophageal perforation that could be managed without surgery. However, Zald et al[28] reported a fatal venous air embolism after dilation by rendezvous.

One of our patients (a 59-year-old male) developed complete oesophageal obstruction due to toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), an idiosyncratic, potentially life-threatening disease characterized by widespread inflammation and necrosis of the epidermis and mucous membranes[29,30]. Mostly caused by a severe adverse event to drugs (e.g., allopurinol or methazolamide)[29], TEN is a very rare disease with an incidence of 0.4-1.2 cases per million person-years. There are very few cases of TEN in the literature, with most encountered in children that resulted in narrowing of the oesophageal lumen through fibrosis and oesophageal obstruction[31]. As far as we know, this is the first report of a rendezvous dilation in a patient suffering from oesophageal complete obstruction caused by TEN.

Several limitations need to be addressed. This is a retrospective study with a small sample size showing a single-centre experience. However, the low number of cases throughout the literature is explained by the rarity of complete obstruction of the hypopharynx/oesophagus. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, we were not able to obtain patients’ FOIS levels prior to the endoscopic rendezvous procedure. However, all patients could not swallow at all prior to the procedure, and this correlates to FOIS level 1. Furthermore, details regarding subsequent dilations after rendezvous procedure were not assessed. However, the time interval between and number of dilations over time varied relevantly, based on individual symptoms.

In conclusion, endoscopic antegrade-retrograde rendezvous dilation offers a safe and viable alternative to high-risk blind antegrade dilation of the proximal oesophagus and hypopharynx or surgical approaches in patients with complete proximal oesophageal obstruction. Although only half of the patients remained PEG-tube independent, the majority of patients improved their ability to swallow. We suggest using scores like the FOIS for standardised clinical follow-up.

Complete oesophageal obstruction is rare and may occur after radiotherapy of head and neck cancers. As antegrade dilation is often unsuccessful, retrograde endoscopic rendezvous dilation can be used to restore oesophageal patency.

This special endoscopic technique is rarely used. Therefore, it is important to analyse its technical and clinical success.

This case series focuses on the clinical outcome of endoscopic retrograde-antegrade rendezvous dilation.

This case series showed a fairly good success rate and noticeably few complications. We contributed further information to the existing literature.

Gastroscopes are instruments for the examination of the upper gastrointestinal tract. A complete obstruction is a completely occluded lumen. Rendezvous procedure means that one endoscope is used from the proximal part and one from the distal part of the complete obstruction.

This case series provides information about the technical and clinical success of antegrade-retrograde rendezvous dilation of complete oesophageal obstructions, which are rare. This endoscopic technique is interesting for other gastroenterologists.

P- Reviewer: Campo SMA, Rabago L S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Coia LR, Myerson RJ, Tepper JE. Late effects of radiation therapy on the gastrointestinal tract. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:1213-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 317] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Laurell G, Kraepelien T, Mavroidis P, Lind BK, Fernberg JO, Beckman M, Lind MG. Stricture of the proximal esophagus in head and neck carcinoma patients after radiotherapy. Cancer. 2003;97:1693-1700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Francis DO, Hall E, Dang JH, Vlacich GR, Netterville JL, Vaezi MF. Outcomes of serial dilation for high-grade radiation-related esophageal strictures in head and neck cancer patients. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:856-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Erdoğan E, Eroğlu E, Tekant G, Yeker Y, Emir H, Sarimurat N, Yeker D. Management of esophagogastric corrosive injuries in children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003;13:289-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Brette M, Aidan K, Halimi B, Cattan P, Grozier F, Sarfati E, Monteil J. [Pharyngo-esophagoplasty by right coloplasty for the treatment of post-caustic pharyngo-laryngeal-esophageal burns: a report of 13 cases]. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2000;117:147-154. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Novacek G. Plummer-Vinson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Thomas GR, Raynor T. Complete esophageal stenosis secondary to peptic stricture in the cervical esophagus: case report. Ear Nose Throat J. 2006;85:187-189. [PubMed] |

| 8. | van Twisk JJ, Brummer RJ, Manni JJ. Retrograde approach to pharyngo-esophageal obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:296-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bueno R, Swanson SJ, Jaklitsch MT, Lukanich JM, Mentzer SJ, Sugarbaker DJ. Combined antegrade and retrograde dilation: a new endoscopic technique in the management of complex esophageal obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:368-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Al-Haddad M, Pungpapong S, Wallace MB, Raimondo M, Woodward TA. Antegrade and retrograde endoscopic approach in the establishment of a neo-esophagus: a novel technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:290-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Moyer MT, Stack BC, Mathew A. Successful recovery of esophageal patency in 2 patients with complete obstruction by using combined antegrade retrograde dilation procedure, needle knife, and EUS needle. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:789-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Petro M, Wein RO, Minocha A. Treatment of a radiation-induced esophageal web with retrograde esophagoscopy and puncture. Am J Otolaryngol. 2005;26:353-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Maple JT, Petersen BT, Baron TH, Kasperbauer JL, Wong Kee Song LM, Larson MV. Endoscopic management of radiation-induced complete upper esophageal obstruction with an antegrade-retrograde rendezvous technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:822-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Schembre D, Dever JB, Glenn M, Bayles S, Brandabur J, Kozarek R. Esophageal reconstitution by simultaneous antegrade/retrograde endoscopy: re-establishing patency of the completely obstructed esophagus. Endoscopy. 2011;43:434-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Crary MA, Mann GD, Groher ME. Initial psychometric assessment of a functional oral intake scale for dysphagia in stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1516-1520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 872] [Cited by in RCA: 1201] [Article Influence: 60.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Caudell JJ, Schaner PE, Desmond RA, Meredith RF, Spencer SA, Bonner JA. Dosimetric factors associated with long-term dysphagia after definitive radiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:403-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lee WT, Akst LM, Adelstein DJ, Saxton JP, Wood BG, Strome M, Butler RS, Esclamado RM. Risk factors for hypopharyngeal/upper esophageal stricture formation after concurrent chemoradiation. Head Neck. 2006;28:808-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mavroidis P, Laurell G, Kraepelien T, Fernberg JO, Lind BK, Brahme A. Determination and clinical verification of dose-response parameters for esophageal stricture from head and neck radiotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2003;42:865-881. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Nutting CM, Morden JP, Harrington KJ, Urbano TG, Bhide SA, Clark C, Miles EA, Miah AB, Newbold K, Tanay M. Parotid-sparing intensity modulated versus conventional radiotherapy in head and neck cancer (PARSPORT): a phase 3 multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:127-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1395] [Cited by in RCA: 1242] [Article Influence: 88.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang JJ, Goldsmith TA, Holman AS, Cianchetti M, Chan AW. Pharyngoesophageal stricture after treatment for head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2012;34:967-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chen AM, Yu Y, Daly ME, Farwell DG, Benedict SH, Purdy JA. Long-term experience with reduced planning target volume margins and intensity-modulated radiotherapy with daily image-guidance for head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2014;36:1766-1772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Grooteman KV, Wong Kee Song LM, Vleggaar FP, Siersema PD, Baron TH. Functional outcome of patients treated for radiation-induced complete esophageal obstruction after successful endoscopic recanalization (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:175-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Goguen LA, Norris CM, Jaklitsch MT, Sullivan CA, Posner MR, Haddad RI, Tishler RB, Burke E, Annino DJ. Combined antegrade and retrograde esophageal dilation for head and neck cancer-related complete esophageal stenosis. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:261-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Huang KL, Liu TY, Huang YC, Leong CP, Lin WC, Pong YP. Functional outcome in acute stroke patients with oropharyngeal Dysphagia after swallowing therapy. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:2547-2553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fowlkes J, Zald PB, Andersen P. Management of complete esophageal stricture after treatment of head and neck cancer using combined anterograde retrograde esophageal dilation. Head Neck. 2012;34:821-825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Dellon ES, Cullen NR, Madanick RD, Buckmire RA, Grimm IS, Weissler MC, Couch ME, Shaheen NJ. Outcomes of a combined antegrade and retrograde approach for dilatation of radiation-induced esophageal strictures (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1122-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mukherjee K, Cash MP, Burkey BB, Yarbrough WG, Netterville JL, Melvin WV. Antegrade and retrograde endoscopy for treatment of esophageal stricture. Am Surg. 2008;74:686-687; discussion 688. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Zald PB, Andersen PE. Fatal central venous air embolism: a rare complication of esophageal dilation by rendezvous. Head Neck. 2011;33:441-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ellender RP, Peters CW, Albritton HL, Garcia AJ, Kaye AD. Clinical considerations for epidermal necrolysis. Ochsner J. 2014;14:413-417. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Sun J, Liu J, Gong QL, Ding GZ, Ma LW, Zhang LC, Lu Y. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a multi-aspect comparative 7-year study from the People’s Republic of China. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:2539-2547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |