Published online Dec 28, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i48.10609

Peer-review started: July 27, 2016

First decision: September 28, 2016

Revised: October 13, 2016

Accepted: November 14, 2016

Article in press: November 16, 2016

Published online: December 28, 2016

Processing time: 154 Days and 13.6 Hours

To evaluate the safety and efficacy of a modified cyanoacrylate [N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate associated with methacryloxysulfolane (NBCA + MS)] to treat non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NV-UGIB).

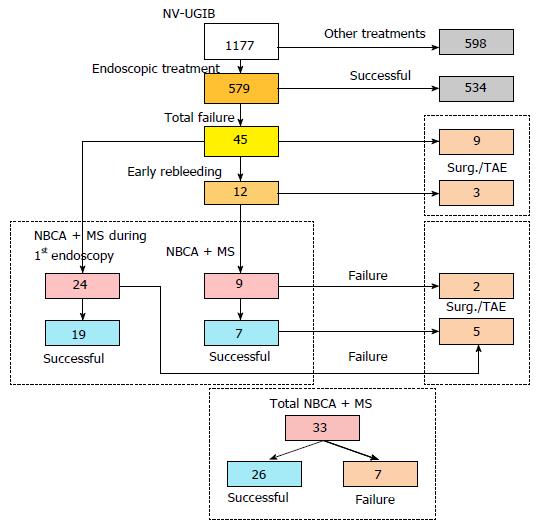

In our retrospective study we took into account 579 out of 1177 patients receiving endoscopic treatment for NV-UGIB admitted to our institution from 2008 to 2015; the remaining 598 patients were treated with other treatments. Initial hemostasis was not achieved in 45 of 579 patients; early rebleeding occurred in 12 of 579 patients. Thirty-three patients were treated with modified cyanoacrylate: 27 patients had duodenal, gastric or anastomotic ulcers, 3 had post-mucosectomy bleeding, 2 had Dieulafoy’s lesions, and 1 had duodenal diverticular bleeding.

Of the 45 patients treated endoscopically without initial hemostasis or with early rebleeding, 33 (76.7%) were treated with modified cyanoacrylate glue, 16 (37.2%) underwent surgery, and 3 (7.0%) were treated with selective transarterial embolization. The mean age of patients treated with NBCA + MS (23 males and 10 females) was 74.5 years. Modified cyanoacrylate was used in 24 patients during the first endoscopy and in 9 patients experiencing rebleeding. Overall, hemostasis was achieved in 26 of 33 patients (78.8%): 19 out of 24 (79.2%) during the first endoscopy and in 7 out of 9 (77.8%) among early rebleeders. Two patients (22.2%) not responding to cyanoacrylate treatment were treated with surgery or transarterial embolization. One patient had early rebleeding after treatment with cyanoacrylate. No late rebleeding during the follow-up or complications related to the glue injection were recorded.

Modified cyanoacrylate solved definitively NV-UGIB after failure of conventional treatment. Some reported life-threatening adverse events with other formulations, advise to use it as last option.

Core tip: Endoscopic hemostasis methods are very effective for managing non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NV-UGIB), but an early rebleeding rate of approximately 10% reduces the success of initial hemostasis. A modified cyanoacrylate (NBCA + MS) glue used for variceal bleeding has occasionally also been used to treat NV-UGIB. In our 7 years of experience, 33 patients were treated with NBCA + MS after conventional treatment modalities failed. Hemostasis was achieved in approximately 80% of these patients. Modified cyanoacrylate effectively treated NV-UGIB after the failure of conventional treatment modalities.

- Citation: Grassia R, Capone P, Iiritano E, Vjero K, Cereatti F, Martinotti M, Rozzi G, Buffoli F. Non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Rescue treatment with a modified cyanoacrylate. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(48): 10609-10616

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i48/10609.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i48.10609

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding is the most common, potentially life-threatening emergency occurring in gastroenterology departments[1]. The condition has an incidence ranging from approximately 50 to 150 per 100000 of the population each year, and the incidence is the highest in areas of the lowest socioeconomic status[1].

In the United States, acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding causes more than 300000 hospital admissions with an annual incidence of hospitalization equal to 1 per 1000 people[2] and a mortality rate of approximately 10%[3]. From a socioeconomic point of view, treating and preventing upper gastrointestinal bleeding costs many billions of dollars per year[4]. Despite the introduction of endoscopic therapies that reduce the rebleeding rate, the mortality rate has only slightly decreased over the last 30 years. This phenomenon is attributed to the increasing occurrence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the elderly. This group has a worse prognosis than others because of their greater use of antiplatelet medications or anticoagulants and their frequent comorbidities[5,6].

Mortality has been reported to be lower in specialist units[7]. This difference is more likely to be due to adherence to protocols and guidelines than to technical developments.

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding can be caused by a wide variety of medical conditions. Peptic ulcers have been reported to be the cause of approximately 50% of upper gastrointestinal bleeding cases, whereas Mallory-Weiss tears account for 5%-15% of cases[8]. Esophageal varices are a common source of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, especially in patients with liver dysfunction and chronic alcoholism. Less frequent causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding include erosive duodenitis, neoplasms, aortoenteric fistulas, vascular lesions, Dieulafoy’s ulcers and prolapse gastropathy[9].

In our country, the large “Prometeostudy”[10] of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding recently showed that peptic lesions were the main cause of bleeding (duodenal ulcer 36.2%, gastric ulcer 29.6%, gastric/duodenal erosion 10.9%). Comorbidities were present in 83% and 52.4% of patients treated with acetyl salicylic acid or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), respectively, and 13.3% of patients had experienced previous episodes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Early rebleeding was observed in 5.4% of patients, and surgery was required in 14.3%. Bleeding-related death occurred in 4.0% of patients.

Endoscopic therapy is typically considered based on the characteristics and the classification of a bleeding ulcer. The Forrest classification is commonly used in Europe and Asia to describe bleeding lesions[11]. Stigmata can be used to predict the risk of further bleeding and the need for therapeutic intervention[12,13].

Approximately 80% of upper gastrointestinal bleeding episodes appear to stop bleeding spontaneously[11]; the approximately 20% of episodes remaining either continue to bleed or will rebleed[14]. The recurrence of gastrointestinal hemorrhage is associated with an increased mortality rate, a greater need for surgery and blood transfusions, a prolonged hospital stay, and increased overall healthcare costs[15].

Endoscopy within the first 24 h is considered the standard of care for the management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding[15].

Endoscopic therapy can be performed by a variety of methods, such as thermal coagulation, sclerotherapy, laser excision, and clip placement. All types of endoscopic therapy are generally considered equivalent, and a combination of methods is superior to an individual therapy[15].

Among the treatments that can be used during endoscopic treatment, cyanoacrylate glues have several advantages: they can be easily and rapidly applied, they are relatively painless, and they eliminate the need for suture removal[16].

Cyanoacrylate is a liquid tissue adhesive that has a well-established utility in the endoscopic management of gastrointestinal variceal bleeding[17-19], but its role in non-variceal bleeding is less clear[19-21]. This limitation is probably related to the limited experience in this area due to the availability of alternative modes of hemostasis, e.g., transarterial embolization, and to the potential side effects of endoscopic cyanoacrylate use in peptic ulcer disease[22]. In fact, despite the relatively safe use of cyanoacrylate glues for treating gastroesophageal variceal bleeding[23], there are concerns about potential serious complications, particularly distant embolization.

Given the possibility of this life-threatening adverse event[21], cyanoacrylate is considered a last resort for achieving endoscopic hemostasis in high surgical risk patients after conventional treatment methods have failed[19].

During the last 20 years, several cyanoacrylate formulations have been developed. In our clinical practice, we have chosen N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate associated with methacryloxysulfolane (NBCA + MS: Glubran® 2) because of its peculiar characteristics. This formulation has hemostatic, sealing, bacteriostatic, adhesive and sclerosing properties. Polymerization begins 1-2 s after application and completes within 60-90 s. The polymerization reaction generates a temperature of approximately 45 °C[24,25], which is lower than that of pure cyanoacrylates[16,26], and this formulation is the only cyanoacrylate glue approved for embolization therapy, as stated in the product’s instructions for use.

In this paper, we retrospectively describe our personal experience using NBCA + MS injections for the management of (NV-UGIB) after the failure of conventional endoscopic modalities.

Between April 2008 and May 2015, 1177 patients were referred to our center for NV-UGIB; 579 (49.2%) of these patients received endoscopic treatment.

Patients in whom initial hemostasis was not achieved or who had early rebleeding were treated with other measures, including surgery, selective transarterial embolization and/or cyanoacrylate glue injections (Figure 1).

NBCA + MS (Glubran® 2, GEM S.r.l.; Italy) were used according to manufacturer’s indications, and all possible precautions were taken to avoid intravasal penetration.

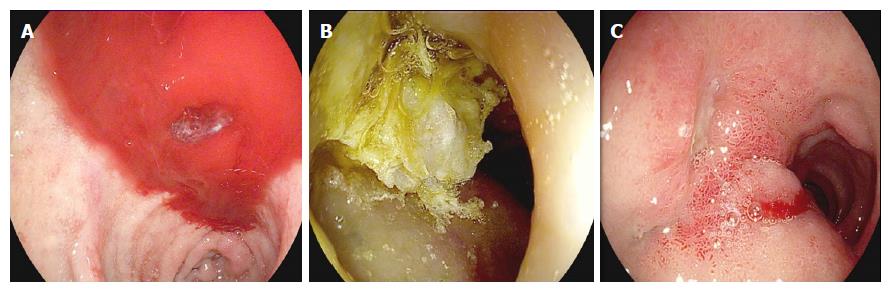

The technique involves injection through a sclerotherapy catheter with a 21- to 25-gauge retractable needle in or around actively bleeding points or non-bleeding vessels (Figure 2).

NBCA + MS is applied deep in the submucosa with an injection needle in 0.5-mL to 1.5-mL boluses around the relevant vessel to “compress” from the outside of the bleeding vessel. The technique is then repeated for each bleeding vessel.

We have used this approach in 24 patients during their first endoscopy and in 9 patients who experienced rebleeding after the initial success of a conventional treatment. Bleeding recurrence was considered in the event of any one of the following: the vomiting of fresh blood, hypotension and melena, or the requirement for more than four units of blood in the 72-h period after endoscopic treatment[23].

All 33 patients have received follow-up examinations to detect eventual rebleeding. Currently, the average follow-up period is 37.6 mo (median, 40; range, 3-57).

Endoscopic hemostasis could not be achieved in 45 of 579 patients (7.8%) with conventional treatments, and early rebleeding occurred in 12 patients (2.1%). Of the 45 patients who did not exhibit initial hemostasis or who had early rebleeding, 33 (76.7%) were treated with cyanoacrylate glue, 16 (37.2%) underwent surgery (including 5 patients in whom cyanoacrylate therapy failed), and 3 (7.0%) were treated with selective transarterial embolization (including 2 patients in whom cyanoacrylate therapy failed).

The group of patients treated with NBCA + MS consisted of 23 males and 10 females; the mean patient age was 74.5 years (median, 78; range, 38-94) (Tables 1 and 2).

| Pat. No. | Age | Gender | Lesion | ASA | Forrest | Presentation | Hb (at entry) | Initial endoscopic treatment | Hemostasis with cyanoacrylate (first endoscopy) | Failure therapy | Follow-up (mo) |

| 1 | 81 | M | DU | III | Ia | Hematemesis | 10.6 | Epi + clip | Yes | No | 45 |

| 2 | 74 | M | GU | II | Ia | Melena | 10.9 | Epi + clip | Yes | No | 51 |

| 3 | 86 | F | G-EMR | III | NA | Hematemesis | 7.6 | Apc | Yes | No | 49 |

| 4 | 74 | M | An-U | III | Ia | Melena | 5.5 | Epi + clip | Yes | No | 40 |

| 5 | 80 | M | DU | IV | Ib | Melena | 8.2 | Clip | Yes | No | 40 |

| 6 | 63 | M | E-EMR | III | NA | Hematemesis | 9.6 | Clip | Yes | No | 47 |

| 7 | 71 | M | GU | II | 2° | Melena | 10.0 | Apc + clip | Yes | No | 57 |

| 8 | 75 | M | DU | II | 2° | Melena | 7.6 | Epi + clip | Yes | No | 49 |

| 9 | 82 | F | DU | III | 2° | Melena | 10.3 | Epi + clip | Yes | No | 40 |

| 10 | 43 | F | DU | I | Ia | Melena | 7.6 | Epi + clip | No | Surgery | 49 |

| 11 | 61 | M | DU | II | Ia | Melena | 8.6 | Epi + clip | No | Surgery | 39 |

| 12 | 85 | F | DU | IV | Ia | Hematemesis | 6.5 | Clip | Yes | No | 35 |

| 13 | 71 | M | DU | III | Ib | Melena | 11.0 | Epi + clip | Yes | No | 39 |

| 14 | 70 | M | GU | II | Ia | Melena | 10.2 | Apc + Epi + clip | Yes | No | 47 |

| 15 | 85 | M | G-Dieulafoy | III | NA | Hematemesis | 9.2 | Clip | Yes | No | 40 |

| 16 | 84 | F | DU | III | Ia | Shock, Hematemesis | 8.0 | Clip | No | Surgery | 39 |

| 17 | 89 | M | GU | III | Ib | Melena | 9.7 | Epi + clip | Yes | No | 42 |

| 18 | 82 | F | DU | II | Ia | Hematemesis | 8.9 | Epi + clip | No | TAE | 45 |

| 19 | 88 | F | DU | III | Ia | Hematemesis | 11.2 | Epi + clip | Yes | No | 34 |

| 20 | 61 | M | An-U | II | 2° | Hematemesis | 7.6 | Epi + clip | No | Surgery | 30 |

| 21 | 41 | M | DU | II | 2° | Hematemesis | 10.7 | Clip | Yes | No | 28 |

| 22 | 63 | M | GU | III | Ib | Hematemesis | 8.1 | Epi + clip | Yes | No | 11 |

| 23 | 81 | M | DU | III | Ia | Melena | 6.8 | Clip | Yes | No | 3 |

| 24 | 74 | M | G-Dieulafoy | III | NA | Hematemesis | 7.2 | Clip | Yes | No | 3 |

| Pat. No. | Age | Gender | Lesion | ASA | Forrest | Presentation | Hb (at entry) | Initial endoscopic treatment | Hemostasis with cyanoacrylate (second endoscopy) | Failure therapy | Follow-up (mo) |

| r1 | 87 | M | DU | III | Ia | Hematemesis | 8.6 | Clip | Yes | No | 38 |

| r2 | 38 | F | An-U | II | Ib | Hematemesis | 7.4 | Clip | No | Surgery | 43 |

| r3 | 76 | M | DD | III | NA | Melena | 7.2 | Clip | Yes | No | 47 |

| r4 | 73 | F | An-U | III | Ia | Hematemesis | 9.7 | Epi + clip | Yes | No | 49 |

| r5 | 82 | M | DU | III | Ia | Hematemesis | 9.3 | Epi + clip | Yes | No | 42 |

| r6 | 94 | M | G-EMR | IV | NA | Melena | 8.6 | Apc | Yes | No | 36 |

| r7 | 87 | F | GU | III | Ib | Melena | 8.8 | Epi + apc | No | TAE | 32 |

| r8 | 78 | M | DU | III | Ia | Melena | 10.4 | Clip | Yes | No | 27 |

| r9 | 80 | M | DU | III | Ia | Hematemesis | 9.0 | Epi + clip | Yes | No | 26 |

The physical status of each patient was classified according to guidelines of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Upon admission, the patients were categorized as follows: 1 patient, (3.0%) class I; 9 patients, (27.3%) class II; 20 patients, (60.6%) class III; and 3 patients, (9.1%) class IV.

The presenting symptomatology was melena in 16 patients (48.5%), hematemesis in 16 patients (48.5%), and shock + hematemesis in 1 patient (3.0%). The average hemoglobin value at admission was 8.81 g/dL (range, 5.5-11.2). Seventeen (51.5%) patients had a duodenal ulcer, 6 (18.2%) had a gastric ulcer, 4 (12.1%) had an anastomotic ulcer, 2 (6.1%) had gastric post-mucosectomy bleeding, 2 (6.1%) had a gastric Dieulafoy’s ulcer, 1 (3.0%) had duodenal diverticular bleeding, and 1 (3.0%) had esophageal post-mucosectomy bleeding.

Regarding the Forrest classification, 16 (48.5%) patients were grade Ia, 6 were grade Ib (18.2%), and 5 were grade IIa (15.2%).

The initial endoscopic treatment consisted of epinephrine (Epi) + clip in 16 patients (48.5%), clip alone in 12 (36.4%), APC (Argon Plasma Coagulation) alone in 2 (6.1%), APC + Epi + clip in 1 (3.0%), Epi + APC in 1 (3.0%), and APC + clip in 1 (3.0%).

Glubran® 2 was used in 24 patients during the first endoscopy and in 9 patients experiencing rebleeding after an initially successful treatment.

Overall, hemostasis was achieved with NBCA + MS in 26 of 33 patients (78.8%). Hemostasis was successfully achieved with NBCA + MS during the first endoscopy in 19 of 24 patients (79.2%). Four patients (16.6%) who did not stop bleeding after the first endoscopy underwent surgery, and 1 (4.2%) was treated with selective transarterial embolization. One patient (4.1%) experienced early rebleeding after being treated with cyanoacrylate.

Of the 9 patients with early rebleeding, 7 (77.8%) achieved hemostasis with NBCA + MS usage, whereas 2 (22.2%) did not and were treated with surgery (1 patient) or transarterial embolization (1 patient).

No late rebleeding occurred during the follow-up period, and no complications related to the glue injections were recorded.

Despite significant positive changes in recent years, NV-UGIB remains a common, challenging and often life threatening emergency for gastroenterologists and endoscopists. Although there have been significant improvements in endoscopic and supportive therapies, the overall mortality rate remains approximately 10% and may even reach 35% in the elderly and in hospitalized patients with serious comorbidities[27].

In most cases, peptic ulcers spontaneously stop bleeding, and high-dose intravenous proton pump inhibitors and endoscopic therapies for bleeding ulcers reduce recurrent bleeding risk and the need for surgery[28].

In approximately 4/5th of all upper gastrointestinal episodes, bleeding stops spontaneously[11], whereas in the remaining 1/5th, the bleeding either continues or will recur, causing a rebleeding episode[14]. Thus, the main open question seems to involve the management of rebleeding.

Because the recurrence of gastrointestinal hemorrhaging increases morbidity, mortality and cost[15], the timely identification and aggressive management of patients at high risk for continued bleeding or rebleeding has become the major focus of upper gastrointestinal bleeding therapy[8].

Rebleeding after initial endotherapy can be controlled in approximately 75% of patients with a second endoscopic treatment, which is safer than undergoing surgery[29].

While cyanoacrylate glue injections effectively control variceal bleeding, the role of the material in NV-UGIB is less defined[30].

When administered by a suitably experienced endoscopist for hemostasis, cyanoacrylate glue is considered a safe, inexpensive and effective salvage alternative to surgery when other measures have failed or if selective transarterial embolization is unavailable[19-21,31]. It is important to note that several different formulations of cyanoacrylate glue are available; these different formulations merit investigation as they may lead significantly different results and safety profiles.

In variceal bleeding, the use of cyanoacrylate is very common and is included in several guidelines. However, few papers have report the results of its use in NV-UGIB, and some are simple case descriptions or short case series[19-20,22]. No direct comparisons of the cyanoacrylate formulations are available.

To the best of our knowledge, the largest (126 patients) and only randomized study was performed by Lee et al[21], who demonstrated significantly lower rebleeding rates in patients with Forrest type Ia lesions treated with a pure N-butyl-cyanoacrylate glue (Histoacryl®) compared with a hypertonic saline-adrenaline (HSE) injection; no overall benefits regarding hemostasis rates were observed in the other patients. However, although no complications followed HSE therapy, arterial embolization with infarction occurred in 2 patients treated with cyanoacrylate, and one of these patients died. Arterial embolization is considered the most dangerous complication of this treatment; therefore, this therapy is typically recommended as a final measure due to the potentially fatal adverse effects[21]. In contrast, in other published papers, complication rates are typically negligible[19,20,22], mirroring the low rates of complications recently reported with the use of cyanoacrylate for varices[23,30].

Our retrospective series of 33 cases supports the efficacy (78.8% success rate) and safety (no side effects) of the modified cyanoacrylate formulation (NBCA + MS) used in our Digestive Endoscopy and Gastroenterology Unit. Compared with other similar, but shorter, case series[19,20,22], the success rate observed in our patients might be due to the fact that we used the glue exclusively as a second-line therapy; in addition, we used a different methodology, i.e., injection only, and our patients had different baseline diseases.

Although our results were obtained from a retrospective series, in our opinion, it would be possible to hypothesize that the lack of complications might be at least partly derived from our long experience in treating variceal bleeding with this product that has been largely documented in digestive endoscopy[29,32-34].

In addition, the differences among the cyanoacrylate formulations might be crucial. In particular, polymerization time and temperature may play a role in this respect. The polymerization time depends on the amount of injected liquid. However, NBCA + MS generally begins to polymerize 1 s to 2 s after application, and the polymerization is complete within 60 s to 90 s. In contrast, other cyanoacrylates take longer (150-180 s) to polymerize[16,26], and these glues only reach maximum mechanical strength upon complete polymerization. The differences regarding the temperature generated by the polymerization reaction appear to be more important than polymerization time. NBCA + MS generates a temperature of approximately 45 °C and thus causes very limited damage to the surrounding tissue[24,25]. In contrast, other cyanoacrylates generate temperatures of 80-90 °C, causing more inflammation and, rarely, tissue necrosis and deep ulcers or fistulas[35].

Some authors consider surgery or selective transarterial embolization to be preferred methods for controlling rebleeding, even though it is accepted that treatments should be largely based on patient comorbidities and surgical risk[22]. In our opinion, NBCA + MS should be implemented before surgery because it is cheaper, is associated with fewer complications, and is very effective (77.8% in our early rebleeding patients), as previously reported by others[19].

Our retrospective observational study indicates that the formulation of cyanoacrylic glue associated with methacryloxysulfolane used in our department was safe and effective for treating NV-UGIB after the failure of conventional treatment modalities. As our results were obtained from a medium size retrospective series, no definitive conclusions can be drawn. In our experience, the glue has been safe and has not caused any side effects. Therefore, in agreement with the literature[21], we suggest its use in high surgical risk patients for endoscopic hemostasis as a last resort, given the possibility of life-threatening adverse events. Finally we consider important to underline that our results are derived from a retrospective observational study: it is well known that retrospective studies have a limited validity compared to randomized clinical trials because the characteristics of the subjects included, the data collected and measured outcomes are defined after the end of the recruitment. Our data have been collected in order to obtain a good level of quality, but, in retrospective studies this cannot be guaranteed. Furthermore, observational studies tend both to overestimate the effects of treatment and to have greater variability in effect estimates because of residual confounding. Hence our results should be read taking into account these possible biases. In our opinion a randomized clinical trial comparing NBCA + MS with the current standard rescue treatments in selected populations is therefore highly advisable.

In the case of positive outcomes, further comparisons with other cyanoacrylate formulations might be useful for establishing the role of NBCA + MS in patients with NV-UGIB after conventional treatments have failed and for clarifying the long-term differences in safety and efficacy.

The authors would like to thank GEM Italy and IBIS Informatica for the manuscript revisions and statistical support.

Endoscopy within the first 24 h is considered the standard of care for the management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Cyanoacrylate has a well-established utility in the endoscopic management of gastrointestinal variceal bleeding, but its role in non-variceal bleeding is less clear.

Several cyanoacrylate formulations are available. The authors use N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate associated with methacryloxysulfolane (NBCA + MS: Glubran® 2) because of its peculiar characteristics: polymerization begins and completes in few second and the polymerization reaction generates a temperature of approximately 45 °C, which is lower than that of other cyanoacrylates. Furthermore this formulation is the only cyanoacrylate glue approved for embolization therapy.

In this paper, the authors retrospectively describe their personal 5-year experience using NBCA + MS for the management of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding after the failure of conventional endoscopic modalities.

In their experience, the glue has been safe and has not caused any side effects. The authors suggest its use in high surgical risk patients for endoscopic hemostasis. Some reported life-threatening adverse events with other formulations, advise to use it as last option. Their results are derived from a retrospective observational study and therefore our results should be read taking into account these possible biases.

The authors conducted a retrospective study regarding the usefulness of modified cyanoacrylates a rescue method for failed hemostasis in NV-UGIB patients. The topic is interesting and the study showed some promising results, although the patient number is small.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Stanley AJ, Yan SL S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu WX

| 1. | Palmer K. Non-variceal upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage: guidelines. Gut. 2002;51 Suppl 4:iv1-iv6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Boonpongmanee S, Fleischer DE, Pezzullo JC, Collier K, Mayoral W, Al-Kawas F, Chutkan R, Lewis JH, Tio TL, Benjamin SB. The frequency of peptic ulcer as a cause of upper-GI bleeding is exaggerated. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:788-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Palmer K. Acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Br Med Bull. 2007;83:307-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jiranek GC, Kozarek RA. A cost-effective approach to the patient with peptic ulcer bleeding. Surg Clin North Am. 1996;76:83-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kaplan RC, Heckbert SR, Koepsell TD, Furberg CD, Polak JF, Schoen RE, Psaty BM. Risk factors for hospitalized gastrointestinal bleeding among older persons. Cardiovascular Health Study Investigators. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:126-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Peter DJ, Dougherty JM. Evaluation of the patient with gastrointestinal bleeding: an evidence based approach. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1999;17:239-261, x. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sanderson JD, Taylor RF, Pugh S, Vicary FR. Specialized gastrointestinal units for the management of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66:654-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rivkin K, Lyakhovetskiy A. Treatment of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62:1159-1170. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Laine L. Gastrointestinal bleeding. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, McGraw-Hill, Hauser SL, Stone RM, Longo DL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine: Textbook, Self-Assessment and Board Review. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional Publishing, 2001: 252. . |

| 10. | Del Piano M, Bianco MA, Cipolletta L, Zambelli A, Chilovi F, Di Matteo G, Pagliarulo M, Ballarè M, Rotondano G. The “Prometeo” study: online collection of clinical data and outcome of Italian patients with acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:e33-e37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim SY, Hyun JJ, Jung SW, Lee SW. Management of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Endosc. 2012;45:220-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Enestvedt BK, Gralnek IM, Mattek N, Lieberman DA, Eisen G. An evaluation of endoscopic indications and findings related to nonvariceal upper-GI hemorrhage in a large multicenter consortium. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:422-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Laine L, Peterson WL. Bleeding peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:717-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 498] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Messmann H, Schaller P, Andus T, Lock G, Vogt W, Gross V, Zirngibl H, Wiedmann KH, Lingenfelser T, Bauch K. Effect of programmed endoscopic follow-up examinations on the rebleeding rate of gastric or duodenal peptic ulcers treated by injection therapy: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 1998;30:583-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Barkun A, Bardou M, Marshall JK. Consensus recommendations for managing patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:843-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Montanaro L, Arciola CR, Cenni E, Ciapetti G, Savioli F, Filippini F, Barsanti LA. Cytotoxicity, blood compatibility and antimicrobial activity of two cyanoacrylate glues for surgical use. Biomaterials. 2001;22:59-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Choudhuri G, Chetri K, Bhat G, Alexander G, Das K, Ghoshal UC, Das K, Chandra P. Long-term efficacy and safety of N-butylcyanoacrylate in endoscopic treatment of gastric varices. Trop Gastroenterol. 2010;31:155-164. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Cheng LF, Wang ZQ, Li CZ, Lin W, Yeo AE, Jin B. Low incidence of complications from endoscopic gastric variceal obturation with butyl cyanoacrylate. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:760-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Repici A, Ferrari A, De Angelis C, Caronna S, Barletti C, Paganin S, Musso A, Carucci P, Debernardi-Venon W, Rizzetto M. Adrenaline plus cyanoacrylate injection for treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers after failure of conventional endoscopic haemostasis. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:349-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kurek K, Baniukiewicz A, Swidnicka-Siergiejko A, Dąbrowski A. Application of cyanoacrylate in difficult-to-arrest acute non-variceal gastrointestinal bleeding. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2014;9:489-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lee KJ, Kim JH, Hahm KB, Cho SW, Park YS. Randomized trial of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate compared with injection of hypertonic saline-epinephrine in the endoscopic treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers. Endoscopy. 2000;32:505-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Loh DC, Wilson RB. Endoscopic management of refractory gastrointestinal non-variceal bleeding using Histoacryl (N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate) glue. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2016;4:232-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cipolletta L, Zambelli A, Bianco MA, De Grazia F, Meucci C, Lupinacci G, Salerno R, Piscopo R, Marmo R, Orsini L. Acrylate glue injection for acutely bleeding oesophageal varices: A prospective cohort study. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:729-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Schug-Pass C, Jacob DA, Rittinghausen J, Lippert H, Köckerling F. Biomechanical properties of (semi-) synthetic glues for mesh fixation in endoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Hernia. 2013;17:773-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kull S, Martinelli I, Briganti E, Losi P, Spiller D, Tonlorenzi S, Soldani G. Glubran2 surgical glue: in vitro evaluation of adhesive and mechanical properties. J Surg Res. 2009;157:e15-e21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Testini M, Lissidini G, Poli E, Gurrado A, Lardo D, Piccinni G. A single-surgeon randomized trial comparing sutures, N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate and human fibrin glue for mesh fixation during primary inguinal hernia repair. Can J Surg. 2010;53:155-160. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Ferguson CB, Mitchell RM. Non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ulster Med J. 2006;75:32-39. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Gralnek IM, Dumonceau JM, Kuipers EJ, Lanas A, Sanders DS, Kurien M, Rotondano G, Hucl T, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Marmo R. Diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:a1-a46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 472] [Cited by in RCA: 497] [Article Influence: 49.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sáenz de Miera Rodríguez A, Baltar Arias R, Vázquez Rodríguez S, Díaz Saa W, Ulla Rocha JL, Vázquez-Sanluis J, Vázquez Astray E. N-Butyl-2-cyanoacrylate plug on fundal varix: persistence 3 years after sclerosis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2009;101:212-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Binmoeller KF, Soehendra N. “Superglue”: the answer to variceal bleeding and fundal varices? Endoscopy. 1995;27:392-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Cameron R, Binmoeller KF. Cyanoacrylate applications in the GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:846-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Battaglia G, MorbinT , Patarnello E, Carta A, Coppa F, Ancona A. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of gastric varices. Acta Endoscopica. 1999;29:97-114. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Seewald S, Sriram PV, Naga M, Fennerty MB, Boyer J, Oberti F, Soehendra N. Cyanoacrylate glue in gastric variceal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2002;34:926-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | López J, Rodriguez K, Targarona EM, Guzman H, Corral I, Gameros R, Reyes A. Systematic review of cyanoacrylate embolization for refractory gastrointestinal fistulae: a promising therapy. Surg Innov. 2015;22:88-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Levrier O, Mekkaoui C, Rolland PH, Murphy K, Cabrol P, Moulin G, Bartoli JM, Raybaud C. Efficacy and low vascular toxicity of embolization with radical versus anionic polymerization of n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA). An experimental study in the swine. J Neuroradiol. 2003;30:95-102. [PubMed] |