Published online Dec 21, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i47.10380

Peer-review started: August 28, 2016

First decision: September 21, 2016

Revised: October 3, 2016

Accepted: October 31, 2016

Article in press: October 31, 2016

Published online: December 21, 2016

Processing time: 114 Days and 4.7 Hours

To characterize radiological and clinical factors associated with subsequent surgical intervention in Crohn’s disease (CD) patients with intra-abdominal fistulae.

From a cohort of 1244 CD patients seen over an eight year period (2006 to 2014), 126 patients were identified as having intra-abdominal fistulae, and included in the study. Baseline patient information was collected from the medical records. Imaging studies were assessed for: anatomic type and number of fistulae; diameter of the inflammatory conglomerate; length of diseased bowel; presence of a stricture with pre-stenotic dilatation; presence of an abscess; lymphadenopathy; and the degree of bowel enhancement. Multivariate analysis for the prediction of abdominal surgery was calculated via Generalized Linear Models.

In total, there were 193 fistulae in 132 patients, the majority (52%) being entero-enteric. Fifty-nine (47%) patients underwent surgery within one year of the imaging study, of which 36 (29%) underwent surgery within one month. Radiologic features that were associated with subsequent surgery included: multiple fistulae (P = 0.009), presence of stricture (P = 0.02), and an entero-vesical fistula (P = 0.01). Evidence of an abscess, lymphadenopathy, or intense bowel enhancement as well as C-reactive protein levels was not associated with an increased rate of surgery. Patients who were treated after the imaging study with combination immunomodulatory and anti-TNF therapy had significantly lower rates of surgery (P = 0.01). In the multivariate analysis, presence of a stricture [RR 4.5 (1.23-16.3), P = 0.02] was the only factor that increased surgery rate.

A bowel stricture is the only factor predicting an increased rate of surgery. Radiological parameters may guide in selecting treatment options in patients with fistulizing CD.

Core tip: We performed a longitudinal cohort study to identify radiological and clinical parameters that are associated with surgery within one-year of diagnosis of fistulae by cross-sectional imaging. We retrospectively reviewed 126 Crohn’s disease (CD) patients with intra-abdominal fistulae. Radiologic features that were associated with subsequent surgery included: multiple fistulae, presence of stricture, and an entero-vesical fistula. Evidence of an abscess, lymphadenopathy, or intense bowel enhancement was not associated with an increased rate of surgery. In multivariate analysis only the presence of a stricture was independently associated with an increased rate of surgery. These findings should be taken in to account when making therapeutic decisions for patients with fistulizing CD.

- Citation: Yaari S, Benson A, Aviran E, Lev Cohain N, Oren R, Sosna J, Israeli E. Factors associated with surgery in patients with intra-abdominal fistulizing Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(47): 10380-10387

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i47/10380.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i47.10380

Entero-invasive sequelae are frequently encountered complications in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD). These invasive complications result from an inflammatory process which triggers the release of a variety of proteases and matrix metalloproteinases in the intestine leading to full-thickness bowel wall injury[1]. This can cause micro-perforation of the intestine, and the development of a fistula, abscess or phlegmon. The reported incidence of invasive complications of CD ranges from 17% to 50%, with approximately half of the fistulae being intra-abdominal[2,3].

Intra-abdominal fistulae are classified clinically into two groups: those which form an internal connection between two bowel layers or segments, and those that occur between the intestine and other organs, such as entero-vesical, rectovaginal, or abdominal wall fistulae[4,5]. The diagnosis of intra-abdominal fistulae is usually made by cross sectional imaging, either with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT), and these imaging modalities are the main tools for assessing the anatomy, extent, and additional anatomic features of the disease[6]. The Lémann Index, which is being developed, incorporates imaging parameters in order to measure cumulative structural bowel damage in patients with CD[7]. However, there is currently no radiological grading system for the assessment of fistulizing CD.

Treatment of intra-abdominal fistulae may be medical or surgical. A prerequisite for medical therapy is the control of local and/or systemic infection. Medications that have been shown in studies to manage perianal and intra-abdominal fistulae include anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, usually in combination with thiopurines[8,9].

Surgery has the advantage of immediate resection of the perforated segment of bowel, and excision of the fistulous tract. Nonetheless, due to high recurrence rates of disease, there is still a need for continuing biologic therapy following surgical intervention. The additional downside of surgery is that repeated resections and/or extensive resections can be associated with short bowel syndrome with metabolic and nutritional derangements.

The choice between surgical and medical treatment of fistulizing CD is often difficult and currently there are no guidelines to help aid in this decision. Furthermore, penetrating CD behavior at onset, has been shown to be associated with a long diagnostic delay[10]. If certain findings on imaging can help guide subsequent management then it may assist clinicians in providing more rapid and appropriate treatment. The aim of this study was to characterize the radiologic features of cross sectional imaging of patients with intra-abdominal penetrating CD, and identify radiological and clinical parameters which are associated with subsequent surgical intervention for CD patients.

In this retrospective, longitudinal study we reviewed the medical records of all patients with an established diagnosis of CD who were seen between February 2006 and August 2014 at the Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center. Patients were included in the study if they were hospitalized or seen as an outpatient at the inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) clinic, had intra-abdominal fistulizing CD according to cross-sectional imaging (CT or MRI) available for analysis, and had a minimum of 1 year follow-up after the imaging study. We excluded all patients who underwent surgery within 6 mo prior to imaging. Penetrating disease at presentation was defined when observed on an imaging study within 12 mo of diagnosis of CD. This time-frame was chosen since there is often a delay in pursuing cross-sectional imaging with new onset CD. This study was reviewed and approved by the Hadassah- Hebrew University Helsinki committee.

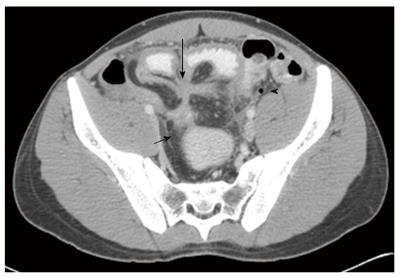

Evaluation of cross sectional imaging was performed by an abdominal radiologist with 15 years of experience in cross sectional imaging (JS), and was blind to clinical data of the patients, including the outcome (surgery). Imaging studies were re-read for the study and assessed for the following radiological signs associated with CD: anatomic type and number of fistulae; diameter of the inflammatory conglomerate; length of diseased bowel; presence of a stricture with pre-stenotic dilatation (defined as a narrowing of 50% or more of the bowel lumen); presence of an abscess, and lymphadenopathy (nodes > 10 mm in short diameter). In addition, the degree of bowel enhancement was assessed according to the study of Colombel et al[11] and rated on a scale of 1-4, with 4 being the most intense bowel enhancement. A representative imaging study is presented in Figure 1.

Baseline patient information was collected from the medical records including: demographics, CD phenotype, medication exposure, and time from disease diagnosis to imaging. Follow-up patient information was collected from medical records, and in those cases in which sufficient information was not available, phone calls or personal interviews were conducted. Post-imaging clinical information that was also collected included medication exposure and surgical details (including the type of surgery and time to surgery).

Due to the increased usage of anti-TNF agents throughout the time period of the study, we divided our cohort into two time periods. The early cohort included patients who had imaging studies performed between February 2006 and December 2009, and the late cohort included patients with imaging studies performed between January 2010 and August 2014.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 21. Univariate analysis was calculated via the student t-test for continuous variables, Wilcoxon and Kolmogorov tests for ordinal variables and Fishers’ Exact Test for categorical variables with Odds Ratio for dichotomous variables.

Multivariate analysis was calculated via Generalized Linear Models using ROC curve for estimating the goodness of fit of the model and Kaplan Meier for censor analysis of duration time to operation with some risk categories defended in advance. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Ron Kedem MD, Phd.

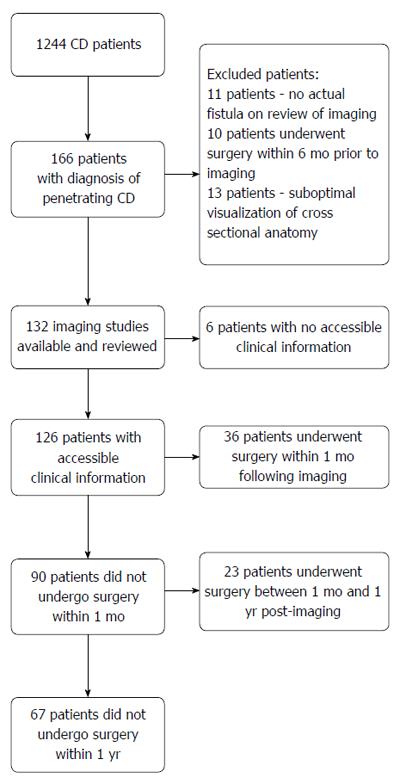

According to documentation by cross-sectional imaging, 166 patients were recorded as having penetrating CD. After evaluation by the research radiologist, imaging studies from 132 patients were found to be eligible for the study. Patients were excluded for the following reasons: 11 patients did not actually have intra-abdominal fistulizing CD, 10 cases were excluded because previous surgery had been performed within 6-mo prior to imaging, and 13 were excluded because the imaging did not enable adequate evaluation of the anatomy (Figure 2).

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are listed in Table 1. Seventy-nine (60%) patients were male with a mean age at the time of imaging of 31 years. Ninety-five percent of the patients were older than 18 years. The average time from diagnosis of CD to imaging was 87 mo, and 28 patients (21%) had fistulizing CD at presentation. Fifteen patients (11%) had prior intra-abdominal surgery as a consequence of their CD and most (90%) patients did not have perianal disease at the time of imaging evaluation.

| Number of patients | 132 |

| Male | 79 (60) |

| Age at diagnosis | 24 (11.6) |

| Age at time of imaging | 31.3 (12.2) |

| Time from diagnosis to imaging, month, mean ± SD | 87 (84) |

| Penetrating disease at presentation | 28 (21) |

| Previous surgery1 | 15 (11) |

| Imaging before 2010 | 66 (50) |

| Treatment during fistula presentation2 | |

| No IM or anti-TNF | 70 (53) |

| Only IM | 33 (26) |

| Only anti-TNF | 11 (8) |

| Anti TNF + IM | 12 (9) |

| Radiological features | |

| Total no. of fistulae | 193 |

| Anatomy of fistulae | |

| Entero-enteric fistula | 103 (52) |

| Entero-colonic fistula | 35 (18) |

| Entero-cutaneous fistula | 28 (14) |

| Entero-vesical fistula | 15 (8) |

| Entero-soft tissue fistula | 12 (6) |

| No. of fistulae per patient | |

| One fistula | 72 (55) |

| Two fistulae | 49 (37) |

| Three or more fistulae | 11 (8) |

| Additional radiological features, n± SD (%) | |

| Diameter of inflammatory conglomerate (cm) | 10 ± 2.6 |

| Length of diseased bowel segment (cm) | 14.8 ± 17.5 |

| Stricture | 31 (23) |

| Abscess | 45 (34) |

| Prominent lymphadenopathy | 40 (30) |

| Treatment after fistula presentation | |

| No IM or anti-TNF | 54 (47) |

| Only IM | 28 (25) |

| Only anti-TNF | 19 (17) |

| Anti TNF + IM | 12 (11) |

Out of 132 patients with at least one fistula on imaging, detailed clinical and surgical treatment characteristics prior to and after imaging were available for 126 patients. At the time of imaging, 70 patients were not treated with immunomodulators (IM) or anti-TNF medications. Thirty-three patients were treated with IM alone, 11 patients with anti-TNF monotherapy and 12 patients with a combination of IM and anti-TNF (Table 1). C-reactive protein (CRP) values were elevated above the normal range in 42% of patients and serum albumin levels were decreased in 30% of patients.

Table 1 depicts the radiological characteristics of the fistulae in the 132 imaging studies that were evaluated. On imaging, 72 (55%) patients had one intra-abdominal fistula, 49 (37%) had two fistulae and 11 (8%) patients had 3 or more fistulae. In total, there were 193 fistulae with the majority of them (52%) being entero-enteric fistulae.

The average diameter of the inflammatory conglomerate was 10 ± 2.6 cm with an average diseased bowel segment of 14.8 ± 17.5 cm. A stricture with pre-stenotic dilatation was present in 31 patients (23%), and an abscess in 45 patients (34%). Prominent lymphadenopathy was present in 40 patients (30%) (Table 1).

After imaging, twelve patients were treated with combination therapy, 28 patients received IM monotherapy, and 19 patients received anti-TNF monotherapy. Fifty-nine (47%) patients in our cohort underwent surgery within one year of the imaging study and, of these, 36 (29%) underwent surgery within one month of the imaging study.

The analysis included 126 patients with adequate clinical and treatment characteristics available (Table 2). Patients treated with combination therapy before imaging had higher rates of surgery within one year of the imaging study as compared to those who did not receive IM or anti-TNF therapy (P = 0.04). In addition, individuals treated with anti-TNF therapy and those treated with combination therapy after imaging had lower rates of surgery as compared to those who did not receive treatment with immunomodulatory agents or anti-TNF therapy (P = 0.01).

| Clinical/laboratory/radiologic parameter | Surgery | No surgery | P value |

| Total no. of patients | 59 (47) | 67 (53) | |

| Age at diagnosis > 18 | 43 (46) | 50 (54) | |

| Age at diagnosis < 18 | 16 (48) | 17 (52) | 0.49 |

| No fistulous disease at presentation | 47 (49) | 48 (51) | |

| Fistulous disease at presentation | 12 (39) | 21 (61) | 0.20 |

| No perianal disease | 53 (46) | 61 (54) | |

| With perianal disease | 6 (50) | 6 (50) | 0.52 |

| Lab parameters | |||

| CRP < 5 mg/L | 31 (45) | 38 (55) | |

| CRP > 5 mg/L | 28 (49) | 29 (51) | 0.39 |

| Albumin > 35 mg/L | 39 (44) | 49 (56) | |

| Albumin < 35 mg/L | 20 (53) | 18 (47) | 0.25 |

| Fistula | |||

| One fistula | 25 (37) | 42 (63) | REF |

| Two fistulae | 24 (50) | 24 (50) | 0.17 |

| Three or more fistulae | 10 (91) | 1 (9) | 0.009 |

| Fistula type (anatomic) | |||

| Entero-enteric | 47 (46) | 56 (54) | REF |

| Entero-vesical | 12 (80) | 3 (20) | 0.01 |

| Entero-colonic | 17 (49) | 18 (51) | 0.45 |

| Entero-cutaneic | 17 (63) | 10 (37) | 0.08 |

| No lymphadenopathy | 40 (44) | 50 (56) | |

| Lymphadenopathy | 19 (53) | 17 (47) | 0.26 |

| No stricture | 40 (41) | 57 (59) | |

| Stricture | 19 (66) | 10 (34) | 0.02 |

| No abscess | 35 (43) | 47 (57) | |

| Abscess | 24 (55) | 20 (45) | 0.14 |

| Bowel enhancement of 1 | 18 (43) | 24 (57) | |

| Bowel enhancement of ≥ 2 | 41 (49) | 43 (51) | 0.33 |

| Treatment before imaging | |||

| No treatment with IM or anti-TNF | 31 (44) | 39 (56) | REF |

| Immunomodulators (IM) | 13 (39) | 20 (61) | 0.98 |

| Anti-TNF | 6 (55) | 5 (45) | 0.46 |

| Anti-TNF + IM | 9 (75) | 3 (25) | 0.04 |

| Treatment after imaging | |||

| No treatment with IM or anti-TNF | 35 (65) | 19 (35) | REF |

| IM | 13 (46) | 15 (54) | 0.18 |

| Anti-TNF | 5 (26) | 14 (74) | 0.01 |

| Anti-TNF + IM | 0 (0) | 12 (100) | 0.01 |

Comparison of patients who did or did not have surgery within one year of the imaging study showed that there were no differences in age at diagnosis or at the time of the imaging study (less or above 18 years), years since diagnosis, time-frame in which the imaging was performed (before or after 2010), history of perianal disease, or fistulous disease on CD presentation. In addition, there were no differences in CRP or serum albumin levels between the two groups. Regarding radiological characteristics, patients with multiple intra-abdominal fistulae had a significantly higher percentage of surgical interventions for CD when compared to those with one fistula (P = 0.009), and this risk increased as the number of fistulae increased. A significantly increased rate of surgery was also demonstrated if a stricture was present on imaging (P = 0.02), as well as for patients with an entero-vesical fistula (P = 0.01). Evidence of an abscess, lymphadenopathy, or intense bowel enhancement on cross-sectional imaging was not associated with an increased rate of surgery.

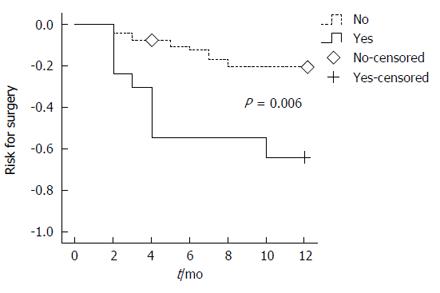

Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier time to surgery curves comparing those with at least one feature associated with surgery (multiple fistulae, stricture or entero-vesical fistula) and those with no features associated with surgery. Over the course of one year post-imaging, there was a significantly higher risk for surgery (P = 0.006) among patients with at least one of the features: multiple fistulae, stricture or entero-vesical fistula.

On analysis of all of the patients who underwent surgery within the first year following surgery, only stricture on imaging was independently associated with surgery [RR = 2.7 (1.02-7.1, P = 0.045)] (Table 3). Three or more fistulae had a borderline association with surgery at one year [RR = 9.2 (0.99-85.8, P = 0.05).

| Parameter | RR (95%CI) | P value |

| Two fistulas | 1.52 (0.65-3.5) | 0.330 |

| Three or more fistulas | 9.23 (0.99-85.8) | 0.051 |

| Stricture | 2.70 (1.02-7.1) | 0.045 |

| Entero-vesical fistula | 3.61 (0.81-16.0) | 0.090 |

| Entero-cutaneous fistula | 2.18 (0.82-5.8) | 0.120 |

| Anti-TNF before imaging | 2.63 (0.71-9.8) | 0.150 |

| Anti-TNF + IM before imaging | 3.86 (0.90-16.6) | 0.070 |

In our study we assessed radiological features of cross-sectional imaging and clinical parameters in patients with fistulizing CD. The presence of intestinal stricture with proximal dilation of the bowel, was the only radiological factor that was independently associated with a higher likelihood of surgery.

The likelihood of needing surgery within one year was low when no risk factors (more than one fistula, stricture or entero-vesical fistula) were present, with more than 90% of the patients being free of surgery. Conversely, among patients who had at least one of the above risk factors, the surgery rate within one year was over 40%.

Fistulizing CD is a common phenotype of CD with up to 50% of patients developing this complication within 20 years of diagnosis[2,3]. Despite this high incidence, evidence regarding medical treatment of fistulizing CD is limited and is focused mainly on perianal fistulizing disease[12]. There are no randomized-controlled trials on the effect of medical treatment for non-perianal fistulizing CD, other than the subgroups of the ACCENT II trial. Moreover, in the ACCENT II trial, less than 10% of the patients on Infliximab had a prior diagnosis of intra-abdominal fistulae[13-15]. Intra-abdominal fistulizing CD comprises a heterogeneous group of patients and conditions, and its treatment is usually individually tailored. Thus, performing prospective studies for assessing the efficacy of treatment options is difficult.

Some retrospective studies and case series have shown a higher surgical rate in patients with entero-vesical fistulae, which may seem to indicate that surgical intervention is preferable in certain clinical situations[16]. This may be due to the increased rate of associated urinary tract infections and hesitance of physicians to initiate immunosuppressive treatment during active infection. However, in our study, the higher risk of surgery associated with an entero-vesical fistula was not significant. In one large retrospective series, nearly all of the patients who underwent surgical management of entero-vesical fistulae had subsequent sustained remission[16]. In a study of 37 patients with entero-vesical fistulae who were initially managed with medical therapy alone, 13 (35%) of the patients maintained remission without surgery for a mean of 4.7 years[17]. In addition, the study showed that sigmoid origination of the entero-vesical fistula and concurrent CD complications, such as abscess or small bowel obstruction, were found to be risk factors for surgery[17].

In our cohort, it is interesting to note that the presence of an abscess in itself was not significantly associated with a higher likelihood of surgery. This is probably due to the efficacy of non-surgical aspiration of abscesses (CT or ultrasound guided), in addition to antibiotic therapy.

Another aspect evaluated in our study was to determine if there was a difference in outcomes of those who had penetrating CD on presentation as compared to those who developed penetrating CD later in the disease course. In the landmark review paper by Cosnes et al[18] approximately 10% of CD patients with ileal involvement presented with penetrating disease, and the cumulative incidence rose to approximately 33% and 50% after 10 and 20 years of follow-up. In our cohort 25% of the patients had penetrating disease within 12 mo of diagnosis while most of the patients developed penetrating disease many years after diagnosis, with an average lag time of approximately seven years. Patients with penetrating disease at onset were not different from the rest of the cohort in regards to demographic or radiological parameters and the need for subsequent surgical intervention.

In our study, more than half of the patients with intra-abdominal fistulae did not have surgery within one year. Of the 31 patients who were treated with anti-TNF therapy after the imaging study, only five (16%) underwent subsequent surgery within one year, and none of the patients on combination therapy underwent surgery. Analysis of the 82 patients who did not receive anti-TNF therapy, showed that 48 (59%) underwent surgery (P < 0.01) (Table 2). These results demonstrate that medical therapy is a valid and often successful treatment option in patients with fistulizing CD, and that treatment with an anti-TNF agent under certain conditions (e.g., when sepsis is controlled) is safe.

Another question we posed was whether medical treatment before the time of imaging conferred a higher risk for surgery. It would seem logical to think that patients who developed an intra-abdominal fistula despite treatment with anti-TNF therapy would be at a higher risk for the need of surgery. This association was significant in the univariate analysis for patients who received combination therapy previous to the imaging study (P = 0.04), but did not reach statistical significance in the multivariate analysis. This may be due to the small number of patients who received combination therapy before the imaging study.

Of note, 48% of the patients were not treated with an anti-TNF agent or IM after imaging diagnosis of the fistula. This study includes patient information dating as far back as 2006, when anti-TNF agents were less accessible due to regulatory constraints. In some instances, patients refused treatment or did not pursue adequate follow-up in the IBD clinic. Patients who received treatment with anti-TNF agents were less likely to undergo surgery than those who did not receive treatment with anti-TNF agents (16% vs 59% respectively, P < 0.05).

The strengths of our study include a systematic and detailed analysis of radiological and clinical parameters that are associated with intra-abdominal fistulae. Furthermore, since a significant percentage of patients were not treated with anti-TNF therapy after the imaging study, this allowed us to directly compare outcomes in these patients to those who were treated with anti-TNF, and thus evaluate the efficacy of this treatment in lowering the rate of surgery within one year.

Our study also has limitations which are mainly due to its retrospective nature. The decision for surgery was influenced, not only by “objective” clinical, laboratory or radiological parameters, but also by the patients' wishes and the preferences of the treating physician. Clinical parameters such as symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain, pneumaturia) were also not analyzed in this study. In order to limit patient bias in the study we included hospitalized patients, as well as ambulatory patients. A significant proportion of the ambulatory patients were seen in the clinic several weeks after the imaging study was performed, and thus clinical parameters could not be assessed reliably for all patients.

Another aspect that this study does not gauge is the quality of life of patients. Often, patients who undergo surgery have a good quality of life in the long term, while patients with medical treatment may not have complete resolution of symptoms and may have a lower quality of life only to undergo bowel resection at a later stage. Nonetheless, surgery is associated with inherent risks and in the majority of these patients there is still a need for continuing biologic therapy in order to prevent recurrent complications. Thus, evaluating long-term quality of life in CD patients to help determine ideal timing of surgery would be difficult in any study.

The timing of surgery for invasive complications of CD has evolved. Initial management of intra-abdominal abscesses, in most cases, is often not surgical and consists of percutaneous drainage and antibiotic administration[19-21]. Given the complexity of patients with fistulizing CD, many management questions still remain, including the role of nutrition and the timing of surgery for patients who fail to achieve a good quality of life with medical treatment. Although difficult to design due to the heterogeneity of fistulizing CD, an effort should be made to undertake prospective studies to determine the best management options for patients with fistulizing CD.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that the presence of a stricture is the only radiological factor that is independently associated with an increased rate of surgery at one year in patients with fistulizing CD. The use of radiological parameters may guide in selecting treatment options.

The choice between surgical and medical treatment of intra-abdominal fistulizing Crohn’s disease (CD) is often difficult and currently there are no guidelines to help aid in this decision. Medications that are efficacious in controlling intra-abdominal fistula include anti TNF agents, usually in combination with thiopurines. Surgery has the advantage of immediate resection of the perforated segment of bowel, and excision of the fistulous tract. Nonetheless, due to high recurrence rates of disease, there is still a need for continuing biologic therapy following surgical intervention.

The authors’ group performed a retrospective cohort study, reviewing 126 cross-sectional studies of patients with intra-abdominal fistulae, and were able to assess that a small bowel stricture was the only independent radiological risk factor for surgery within 1-year. Not less importantly was the finding that all other radiological features (e.g., presence of an abscess, significant lymphadenopathy) were not associated with surgery and could be treated by other measures (e.g., computed tomography (CT)-guided drainage of the abscess, medical therapy).

This study suggests that with detailed analysis of cross-sectional imaging of CD patients that present with intra-abdominal fistulae, the risk for surgery (i.e., failure of medical therapy), can be attained.

The findings of this study may assist clinicians in making a decision for regarding treatment options of CD patient with intra-abdominal fistulae. A patient with the lack of specific radiological parameters (small bowel-stricture) has an excellent chance for deferring surgery if treated pharmacologically.

Intra-abdominal fistulae are classified clinically into two groups: those which form an internal connection between two bowel layers or segments, and those that occur between the intestine and other organs, such as entero-vesical, rectovaginal, or abdominal wall fistulae. The diagnosis of intra-abdominal fistulae is usually made by cross sectional imaging, either with magnetic resonance imaging or CT, and these imaging modalities are the main tools for assessing the anatomy, extent, and additional anatomic features of the disease.

The authors report on patients with CD and imaging and evidence of fistulae. The authors assess radiographic findings and correlate these with the primary outcome of undergoing surgery within a year of the imaging study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Israel

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Cologne KG, Limongelli P, Melton GB, Lakatos PL S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Siegmund B, Feakins RM, Barmias G, Ludvig JC, Teixeira FV, Rogler G, Scharl M. Results of the Fifth Scientific Workshop of the ECCO (II): Pathophysiology of Perianal Fistulizing Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:377-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bell SJ, Williams AB, Wiesel P, Wilkinson K, Cohen RC, Kamm MA. The clinical course of fistulating Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1145-1151. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Schwartz DA, Loftus EV, Tremaine WJ, Panaccione R, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:875-880. [PubMed] |

| 4. | D’Haens G. Medical management of major internal fistulae in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6:244-245. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Present DH. Urinary tract fistulas in Crohn’s disease: surgery versus medical therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2165-2167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Panes J, Bouhnik Y, Reinisch W, Stoker J, Taylor SA, Baumgart DC, Danese S, Halligan S, Marincek B, Matos C. Imaging techniques for assessment of inflammatory bowel disease: joint ECCO and ESGAR evidence-based consensus guidelines. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:556-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 539] [Cited by in RCA: 478] [Article Influence: 39.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pariente B, Mary JY, Danese S, Chowers Y, De Cruz P, D’Haens G, Loftus EV, Louis E, Panés J, Schölmerich J. Development of the Lémann index to assess digestive tract damage in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:52-63.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, van Hogezand RA, Podolsky DK, Sands BE, Braakman T, DeWoody KL. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1969] [Cited by in RCA: 1839] [Article Influence: 70.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Present DH, Korelitz BI, Wisch N, Glass JL, Sachar DB, Pasternack BS. Treatment of Crohn’s disease with 6-mercaptopurine. A long-term, randomized, double-blind study. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:981-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 802] [Cited by in RCA: 706] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Moon CM, Jung SA, Kim SE, Song HJ, Jung Y, Ye BD, Cheon JH, Kim YS, Kim YH, Kim JS. Clinical Factors and Disease Course Related to Diagnostic Delay in Korean Crohn’s Disease Patients: Results from the CONNECT Study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Colombel JF, Solem CA, Sandborn WJ, Booya F, Loftus EV, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Bodily KD, Fletcher JG. Quantitative measurement and visual assessment of ileal Crohn’s disease activity by computed tomography enterography: correlation with endoscopic severity and C reactive protein. Gut. 2006;55:1561-1567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bemelman WA, Allez M. The surgical intervention: earlier or never? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;28:497-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sands BE, Blank MA, Patel K, van Deventer SJ. Long-term treatment of rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: response to infliximab in the ACCENT II Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:912-920. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, Chey WY, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Kamm MA, Korzenik JR, Lashner BA, Onken JE. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1581] [Cited by in RCA: 1553] [Article Influence: 74.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dignass A, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, Lémann M, Söderholm J, Colombel JF, Danese S, D’Hoore A, Gassull M, Gomollón F. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: Current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:28-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1118] [Cited by in RCA: 1032] [Article Influence: 68.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Taxonera C, Barreiro-de-Acosta M, Bastida G, Martinez-Gonzalez J, Merino O, García-Sánchez V, Gisbert JP, Marín-Jiménez I, López-Serrano P, Gómez-García M. Outcomes of Medical and Surgical Therapy for Entero-urinary Fistulas in Crohn’s Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:657-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhang W, Zhu W, Li Y, Zuo L, Wang H, Li N, Li J. The respective role of medical and surgical therapy for enterovesical fistula in Crohn’s disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:708-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1785-1794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1390] [Cited by in RCA: 1560] [Article Influence: 111.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Feagins LA, Holubar SD, Kane SV, Spechler SJ. Current strategies in the management of intra-abdominal abscesses in Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:842-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | de Groof EJ, Carbonnel F, Buskens CJ, Bemelman WA. Abdominal abscess in Crohn’s disease: multidisciplinary management. Dig Dis. 2014;32 Suppl 1:103-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nguyen DL, Sandborn WJ, Loftus EV, Larson DW, Fletcher JG, Becker B, Mandrekar J, Harmsen WS, Bruining DH. Similar outcomes of surgical and medical treatment of intra-abdominal abscesses in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:400-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |