Published online Nov 28, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i44.9836

Peer-review started: June 30, 2016

First decision: August 08, 2016

Revised: August 26, 2016

Accepted: September 28, 2016

Article in press: September 28, 2016

Published online: November 28, 2016

Processing time: 150 Days and 19.9 Hours

To investigate the characteristic features of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seroclearance among Korean hepatitis B virus (HBV) carriers.

Carriers with HBsAg seroclearance were selected by analyzing longitudinal data collected from 2003 to 2015. The period of time from enrollment to the negative conversion of HBsAg (HBsAg-NC) was compared by stratifying various factors, including age, sex, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), HBV DNA, sequential changes in the signal-to-cutoff ratio of HBsAg (HBsAg-SCR), as measured by qualitative HBsAg assay, and chronic liver disease on ultrasonography (US-CLD). Quantification of HBV DNA and HBsAg (HBsAg-QNT) in the serum was performed by commercial assay.

Among the 1919 carriers, 90 (4.7%) exhibited HBsAg-NC at 6.2 ± 3.6 years after registration, with no differences observed among the different age groups. Among these carriers, the percentages of those with asymptomatic liver cirrhosis (LC) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) at registration were 31% and 7.8%, respectively. The frequency of HBsAg-NC significantly differed according to the HBV DNA titer and US-CLD. HBeAg influenced HBsAg-NC in the 40-50 and 50-60 year age groups. HBsAg-SCR < 1000 was correlated with an HBsAg-QNT < 200 IU/mL. A gradual decrease in the HBsAg-SCR to < 1000 predicted HBsAg-NC. Six patients developed HCC after registration, including two before and four after HBsAg-NC. The rate at which the patients developed new HCC after HBsAg seroclearance was 4.8%. LC with excessive drinking and vertical infection were found to be risk factors for HCC in the HBsAg-NC group.

HCC surveillance should be continued after HBsAg seroclearance. An HBsAg-SCR < 1000 and its decrease in sequential testing are worth noting as predictive markers of HBsAg loss.

Core tip: In South Korea, where most hepatitis B virus carriers are infected with genotype C, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seroclearance rate is 4.7%, and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) after HBsAg loss is 4.8%. In patients with HBsAg seroclearance, the percentages of asymptomatic liver cirrhosis (LC) and HCC are 31% and 7.8% at enrollment, respectively. A signal-to-cutoff ratio of the qualitative HBsAg level of less than 1000 and its sequential decrease are worth noting as predictive markers of HBsAg loss. HCC surveillance should be continued after HBsAg seroclearance, particularly in patients with LC.

- Citation: Park YM, Lee SG. Clinical features of HBsAg seroclearance in hepatitis B virus carriers in South Korea: A retrospective longitudinal study. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(44): 9836-9843

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i44/9836.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i44.9836

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the most important cause of liver cirrhosis (LC) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in endemic areas worldwide[1,2]. The natural course of HBV infection is associated with immunological changes that occur in three phases: tolerance, eradication, and recovery[3]. These phases are classified based on the serum aminotransferase level, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and HBV DNA titers, which represent hepatitis and viral replication, respectively[4,5]. Recovery is defined as ceasing of the self-replicating activity of the HBV genome and its transition to a non-replicating state. In general, a serum HBV DNA level of below 2000 IU/mL is considered to indicate an inactive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) carrier state[3,5-7]. Once the HBV genome is inactivated, it remains inert throughout life, HBeAg becomes negative, and HBsAg is cleared in approximately 40% of patients after 25 years of follow-up[3]. On the other hand, a significant proportion of carriers with HBeAg loss harbor the G1896A mutation, the so-called e-minus mutation[2]. In Korea, where most HBV carriers harbor genotype C2[8-10], most carriers over the age of 40 are infected with HBV with basal core promoter (BCP) double mutations (A1762G and A1764T), and more than half of these individuals have the G1896A mutation[9,10]. These mutations are associated with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis that is frequently reactivated[2,11,12], and HBeAg seroconversion is associated with the development of LC and HCC in two-thirds of carriers[2,7,13]. Because the turning point of seroconversion generally occurs near the age of 40[11], the recovery phase and timing of mutations usually overlap with the development of LC and HCC at this time[2,14]. However, HCC may also develop after HBsAg seroclearance[2,14]. These results highlight the difficulty of determining when and how the negative conversion of HBsAg (HBsAg-NC) in the serum takes the risk out of HCC. Thus, Korean HBV carriers represent a good model to study the clinical significance of HBsAg seroclearance in individuals with genotype C. This study investigated the long-term process of HBsAg seroclearance to elucidate the outcomes and predictive factors.

Among chronic HBV carriers who visited the Hepatology Center of Bundang Jesaeng General Hospital between March 2003 and September 2015, all patients with HBsAg seroclearance were recruited. The clinical and laboratory data were retrospectively recorded at baseline and during follow-up. Chronic carriers were defined as those with HBsAg positivity on two successive tests performed at least six months apart. Registration or entry was defined as the initial visit to the center. The baseline data included the data collected at the first visit. HBsAg seroclearance was defined as two consecutive negative HBsAg tests performed at least six months apart.

The patients underwent tests for biochemical liver function, hepatitis B virological markers, and alpha-fetoprotein, as well as liver ultrasonography (US). The virological markers assessed included HBsAg, anti-HBs, HBeAg, anti-HBe, and HBV DNA. The anti-HBs or anti-HBe test was performed as clinically indicated. The anti-HCV test was performed at baseline and was repeated if the alanine aminotransferase level was elevated to more than twice the upper limit of normal. The signal-to-cutoff ratio of the HBsAg (HBsAg-SCR) level was measured for each patient by qualitative assay.

The HBsAg, anti-HBs, HBeAg and anti-HBe levels were determined by ARCHITECT qualitative assay, which is a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA) that measures the resulting chemiluminescent reaction as relative light units (RLUs) (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL, United States). There is a direct relationship between the amount of HBsAg in a sample and the RLUs detected by ARCHITECT assay (Abbott Laboratories). The anti-HCV levels were determined using a third-generation enzyme immunoassay (Abbott Laboratories). HBV DNA was tested using a commercially available real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR; Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, CA, United States), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The lower limit of detection for the Roche assays is 20 IU/mL. The viral load data obtained with the Roche assay were converted to international reference units for analysis using approximations for 1 pg (283000 copies) and 1 IU/mL (5.8 copies/mL).

The data on the HBsAg levels in 177 patients were separately collected to perform correlation analysis with the HBsAg-SCRs obtained with CMIA. The HBsAg quantification (HBsAg-QNT) was measured by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay using an Elecsys HBsAg II Quant Assay (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, United States), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This approach quantifies HBsAg against an internal World Health Organization reference standard in IU/mL.

To compare the characteristics between groups, either the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze categorical variables, and Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon nonparametric test was used to analyze continuous variables. Statistical data were expressed as the mean ± SD. The correlation between the HBsAg-SCR and HBsAg-QNT was analyzed. The statistical procedures were performed with R-project version 3.2[15]. P values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

Negative seroconversion of HBsAg was observed in 90 of 1919 carriers (4.7%), with an estimated annual rate was 0.76%. The rate of HBsAg loss was higher in the carriers over the age of 40 than in the younger carriers (5.7% vs 2.5%, P = 0.001). Among the carriers with HBsAg seroclearance, male predominance was more significant in the 40-50 and 50-60 year age groups than in the 30-40 and > 60 year age groups (P < 0.0001). The period of time until HBsAg clearance after registration was 6.48 ± 3.76 years. This value did not significantly differ among the age groups (P = 0.148) (Table 1).

| Age group | Total number | 1HBsAg seroclearance | Time interval to HBsAg seroclearance |

| (sex ratio) | No. (rate/yr/sex ratio) | (yr, mean ± SD) | |

| < 30 | 181 (1.8:1) | 4 (2.2%/0.55%/3.0:1) | 3.99 ± 2.91 |

| 30-40 | 423 (2.3:1) | 11 (2.6%/0.45%/1.2:1) | 5.79 ± 4.23 |

| 40-50 | 574 (2.9:1) | 36 (6.3%/0.92%/4.0:1) | 6.87 ± 3.5 |

| 50-60 | 455 (0.4:1) | 22 (4.8%/0.79%/2.7:1) | 6.15 ± 3.89 |

| > 59 | 286 (1.1:1) | 17 (5.9%/1.05%/0.9:1) | 5.64 ± 3.14 |

| Total | 1919 (1.4:1) | 90 (4.7%/0.76%/1.9:1) | 6.2 ± 3.6 |

Among the 90 carriers with HBsAg seroclearance, 82.2% were HBeAg-negative at registration. Among these HBeAg-negative carriers, 95.3% had no history of anti-viral treatment and were considered to be in the inactive phase. The time interval to HBsAg clearance did not differ between the HBeAg-positive and negative carriers (P = 0.982). Among the carriers with HBsAg seroclearance who had a treatment history, the time interval to HBsAg clearance did not differ between the HBeAg-positive and negative carriers (8.13 ± 3.12 vs 7.95 ± 3.45 years, P = 0.4442). However, this time interval was longer for the carriers who had received treatment than for those who had not received treatment (7.95 ± 3.34 vs 5.52 ± 3.48 years, P = 0.017), suggesting that anti-viral therapy does not lead to HBsAg seroclearance[16,17]. On the other hand, the time interval from entry to HBsAg seroclearance was significantly longer for the HBeAg-positive carriers than for the HBeAg-negative carriers in the 40s and 50s age groups (9.24 ± 2.49 years vs 6.18 ± 3.63 years, P = 0.013) (Table 2). Likewise, the time interval was significantly longer for the carriers with an HBV DNA level of > 2000 IU/mL than for those with a level of < 20 IU/mL (8.31 ± 3.26 years vs 4.92 ± 3.36 years; P = 0.0005) (Table 3). Data on the BCP double mutations, A1762G and A1764T, and the e-minus mutation, G1896A, were available for 18 patients. Women were predominant in the wild-type BCP group, whereas men were predominant in the mutant group (male/female = 1/6 vs 9/2, respectively; P = 0.0014). The BCP mutation carriers tended to be older than the wild-type carriers (41.9 ± 10.8 years vs 48.5 ± 7.6 years old, P = 0.0725). However, the time interval from entry to HBsAg seroclearance did not differ between the groups.

| HBeAg-positive | HBeAg-negative | |||

| Age group | n (%) | Years (mean ± SD) | n (%) | Years (mean ± SD) |

| < 30 | 1 (25) | 8.15 | 3 (75) | 2.6 ± 1.06 |

| 30-40 | 4 (36.4) | 5.87 ± 4.9 | 7 (63.6) | 5.75 ± 4.21 |

| 40-50 | 6 (16.7) | 9.24 ± 2.84 | 30 (83.3) | 6.4 ± 3.46 |

| 50-60 | 2 (9.1) | 9.22 ± 1.71 | 20 (90.9) | 5.84 ± 3.93 |

| > 59 | 3 (17.6) | 3.38 ± 1.81 | 14 (82.4) | 6.12 ± 3.2 |

| Total | 16 (17.8) | 7.23 ± 3.71 | 74 (82.2) | 5.98 ± 3.2 |

| HBV DNA < 201 IU/mL | HBV DNA 20-2000 IU/mL | HBV DNA > 2000 IU/mL | ||||

| Age group | No. | Years (mean ± SD) | No. | Years (mean ± SD) | No. | Years (mean ± SD) |

| < 30 | 2 | 2.31 ± 1.32 | 2 | 5.67 ± 3.51 | 0 | 0 |

| 30-40 | 4 | 6.42 ± 4.82 | 4 | 3.72 ± 4.01 | 3 | 7.72 ± 3.92 |

| 40-50 | 12 | 5.73 ± 3.73 | 14 | 6.71 ± 3.36 | 10 | 8.47 ± 3.11 |

| 50-60 | 12 | 3.94 ± 2.99 | 6 | 8.36 ± 3.43 | 4 | 9.47 ± 3.11 |

| > 59 | 9 | 5.07 ± 2.85 | 5 | 5.95 ± 3.28 | 3 | 6.82 ± 4.6 |

| SUM | 39 | 4.92 ± 3.36 | 31 | 6.45 ± 3.49 | 20 | 8.31 ± 3.26 |

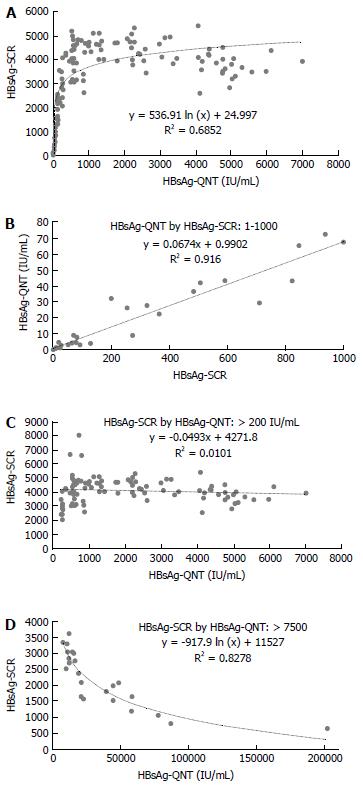

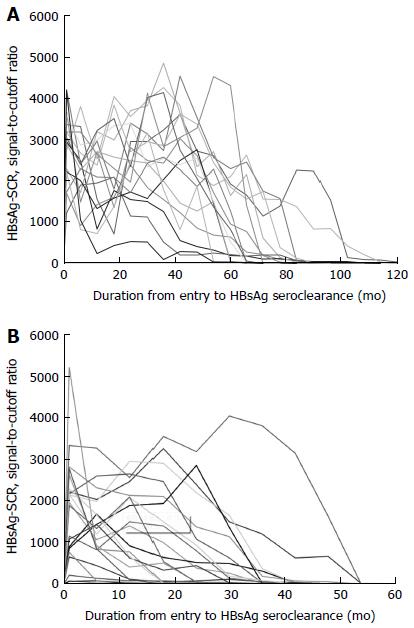

A log-linear-shaped correlation was detected between the HBsAg-SCR and HBsAg-QNT (Figure 1A), and a good correlation with a linear drift curve was observed between an HBsAg-SCR < 1000 and an HBsAg-QNT < 100 IU/mL (y = 0.0674x + 0.9902, R² = 0.916) (Figure 1B). No correlation was observed between these two values in the patients with HBsAg-QNT levels of over 200 IU/mL (Figure 1C). An inverse correlation was observed in the patients with very high HBsAg titers of over 10000 IU/mL (Figure 1D), indicating a prozone effect on the HBsAg-SCR caused by excess antigen. Based on the HBsAg-SCR value of 1000, we arbitrarily divided the 90 carriers with HBsAg seroclearance into two groups. The period of time from entry to HBsAg seroclearance was significantly shorter in the < 1000 group than in the ≥ 1000 group (5.07 ± 3.74 years vs 7.47 ± 3.05 years, P = 0.0008). Moreover, a sequential decrease in the HBsAg-SCR was predictive of HBsAg-NC in every case (Figure 2). The HBeAg-positive rate was significantly higher in the ≥ 1,000 group than in the < 1000 group (25% vs 11.9%, P = 0.0057). Further, the mean age in the < 1000 group tended to be higher than that in the ≥ 1000 group (46.2 ± 11 years vs 50 ± 11.1 years old, P = 0.0593). However, there was no difference in the sex ratio or the prevalence of HCC or LC between the two groups.

We classified the patients with HBsAg seroclearance into the following three groups according to their US findings: normal, non-cirrhotic chronic liver disease (CLD) and cirrhotic. The period of time from study entry to HBsAg loss was significantly shorter in the normal US group than in the CLD and cirrhotic US groups (5.05 ± 3.92, 6.86 ± 3.51 years and 6.8 ± 2.98 years, respectively; normal US vs CLD, P = 0.0259; normal vs cirrhotic US, P = 0.0366) (Table 4). Among the 90 patients with HBsAg seroclearance, 31% had asymptomatic, inactive LC without HCC at registration. Men were predominant in the 30s (3/3) and 40s (9/10) age groups, but the proportion of females was increased in the 50s (3/5) and 60s (5/10) age groups. Five patients (17.9% of 28; male/female = 4/1) developed HCC during follow-up, including one before and four after HBsAg loss.

| Age group | Normal US | Non-cirrhotic CLD | Cirrhotic US | |||

| No. | Year (mean ± SD) | No. | Year (mean ± SD) | No. | Year (mean ± SD) | |

| < 30 | 2 | 2.29 ± 1.28 | 2 | 5.7 ± 3.47 | 0 | - |

| 30-40 | 9 | 5.48 ± 4.59 | 1 | 5.56 | 1 | 5.6 |

| 40-50 | 9 | 5.7 ± 4.07 | 16 | 7.2 ± 3.63 | 11 | 7.35 ± 2.86 |

| 50-60 | 9 | 5 ± 4.23 | 8 | 6.59 ± 4.3 | 5 | 7.51 ± 2.38 |

| > 59 | 3 | 3.81 ± 1.49 | 7 | 6.91 ± 3.17 | 7 | 5.14 ± 3.42 |

| SUM | 32 | 5.05 ± 3.92 | 34 | 6.86 ± 3.51 | 24 | 6.8 ± 2.98 |

Among the 90 patients with HBsAg seroclearance, thirteen were diagnosed with HCC, including seven (7.8%) at registration (HCC group-1) and six (6.7%) during follow-up (HCC group-2). Among the patients in HCC group-2, two developed HCC prior to HBsAg loss, and four developed HCC at 0.66 ± 0.63 years after HBsAg loss, corresponding to a rate of 4.8% among the 83 carriers without HCC at entry. There was no difference in the time interval from entry to HBsAg loss between HCC group-1 and group-2 (6.78 ± 2.77 years and 5.77 ± 3.18 years, respectively). In addition to LC, the risk factors for HCC included excessive drinking in three men and vertical infection in one woman.

We summarize here five important key findings regarding HBsAg seroclearance in Korean HBV carriers from a new perspective. First, HBsAg-SCR, HBeAg, HBV DNA and CLD are factors associated with the time interval from a given carrier state to HBsAg seroclearance. Second, the start of a decrease in HBsAg-SCR usually indicates the gradual loss of HBsAg quantity. Third, asymptomatic, inactive LC is present in approximately 30% of carriers with HBsAg seroclearance. Fourth, HCC can develop after HBsAg loss. Fifth, in addition to LC, risk factors for HCC may include excessive drinking and a family history of HBV infection.

The HBsAg clearance rate seems to be lower in Korea than in other countries. The clearance rate was determined to be 0.76% in Korea, while other studies have reported rates of 1.15%-1.6% in Taiwan[6,18], 1.14% in Kawerau of New Zealand[19], 1%-1.9% in Caucasian carriers[5,17], 2.5% in the Goto Islands of Japan[20], and 3.08% in China[21]. Compared with data from Taiwan[18], HBsAg seroclearance in Korea was significantly reduced in all age groups as follows: 0.55% vs 0.77% in the 20-30 year, 0.45% vs 1.07% in the 30-40 year, 0.92% vs 1.65% in the 40-50 year, and 0.89% vs 1.83% in the 50 and over age groups. This variability may be due to various factors, such as geographic differences in genotypes, age, gender, viral loading and fibrosis at enrollment. For instance, almost all Korean carriers are known to be infected with genotype C, whereas 60% and 34% of Taiwanese carriers are infected with genotypes B and C, respectively[6,22].

Carriers with an initial HBeAg-positive result show the gradual negative conversion of HBeAg and HBV DNA before the loss of HBsAg[14]. In carriers with an initial HBeAg-negative result, HBV DNA is cleared from the serum before HBsAg-NC, although low HBV DNA titers are persistently detected in some patients[23]. These results are inter-related in that the HBsAg loss is usually preceded by a long period of inactive disease[17].

The time period from entry to HBsAg loss in our study is similar to that reported in a previous six-year study conducted in China[21]. Notably, no significant differences in this time interval were observed according to age, the HBeAg status or the HBV DNA titer at the time of enrollment. Two opposite conclusions have been made regarding the role of HBV DNA in HBsAg seroclearance. One is that HBV DNA is not a dependent factor for HBsAg-NC[6,19], while the other suggests that lower viral loads are predictive of HBsAg seroclearance[24]. In our study, the HBV DNA titer was associated with the relative period of time from detection of viral activity to HBsAg seroclearance, and this period was at least 1.5 times longer in the carriers with HBV DNA levels ≥ 2000 IU/mL than in those with levels < 20 IU/mL 40s. However 50s, HBeAg exhibited this effect only in the 40s and 50s age groups, indicating its age-dependent role in predicting HBsAg loss, in contrast with the HBV DNA titer.

The baseline HBsAg level is known to be a better predictor of HBsAg seroclearance than other factors[6,16,19,21,24-26]. This statement applies to inactive carrier, in whom a lower HBsAg level is more predictive of HBsAg seroclearance. Reportedly, the optimum cut-off baseline HBsAg level has varied among studies, for example, studies have reported levels of < 10 IU/mL[6,21], < 100 IU/mL[19,24], < 200 IU/mL[25,26], and < 751 IU/mL[16]. In addition, it has been reported that the predictive capacity of the HBsAg level can be improved by considering it in combination with other factors, such as a normal platelet count[21], old age[19], an undetectable HBV DNA level[24], the HBV DNA level at 12 mo after HBeAg seroconversion[27], and a yearly ≥ 0.5 log IU/mL reduction[25,26].

Because the quantitative HBsAg test is expensive, we analyzed the utility of the HBsAg-SCR in predicting HBsAg seroclearance. A good linear correlation was observed between an HBsAg-SCR < 1000 and HBsAg-QNT < 200 IU/mL. In addition, a prozone effect on the HBsAg-SCR caused by excess antigen was observed among the carriers with excessive HBsAg titers of > 10000 IU/mL, most of whom had a very high serum HBV DNA level of > 7 log10 IU/mL. With the exception of those carriers with highly replicative infections, the HBsAg-SCR was significantly reduced in the HBeAg-negative carriers compared with the HBeAg-positive carriers. Moreover, the period of time from a given viral state to HBsAg loss tended to be shorter, as shown in Figure 2. A gradual decrease in the repeated tests during follow-up usually indicated HBsAg loss within five years. These results suggest that sequential HBsAg-SCR data are very useful for predicting HBsAg seroclearance.

The rate of LC at entry of 31.1% for the carriers with HBsAg seroclearance is similar to that reported previously[14]. These results indicate that LC is present in an appreciably high rate of carriers with HBsAg seroclearance. On the other hand, significant fibrosis has been reported to be more prevalent in patients with HBsAg seroclearance who are > 50 years of age compared with those who are < 50 years of age[19,28]. In our study, the prevalence of LC was significantly increased among the males who were approximately forty years of age. In addition, the carriers in whom LC/CLD was detected on US exhibited a longer time interval from entry to HBsAg seroclearance than those with normal US results. These results suggest that the correlation between age and HBsAg loss is meaningful when it is considered together with gender and LC. In addition, the frequency of HBsAg loss was higher in the carriers over the age of 40 than in the younger carriers, and this trend is similar to trends reported in Taiwan[18], Japan[20], and New Zealand[29]. These results might be associated with a high rate of HBsAg seroclearance during long-term follow-up, as reported in Chu and Liaw’s study[18].

Inactive carriers generally have a good prognosis. Indeed, none of the patients developed HCC following HBsAg loss (median follow-up of 72 mo) in a community study conducted in Kawerau, New Zealand[19], or in a study of Caucasians[5]. In contrast, in studies performed in Hong Kong and the United States, 1.4%-2.4% of the patients developed HCC after HBsAg seroclearance[7,14,28]. In our study, 4.82% of the carriers with HBsAg seroclearance developed HCC after HBsAg loss, indicating that HBsAg seroclearance does not guarantee patient safety out of HCC.

In one study, HBsAg seroclearance in individuals < 50 years of age has been shown to be associated with a lower risk of the development of HCC[28]. In another study, a low baseline level of albumin and family histories of HBsAg positivity and HCC have been demonstrated to be associated with a high risk of development of HCC, even in individuals who are < 50 years of age at the time of HBsAg clearance[14]. In our study, HCC developed in one patient over 50 years of age and in three patients over 60 years of age after HBsAg seroclearance. All patients had asymptomatic LC at registration and no evidence of deterioration of liver function during follow-up. In addition, none of these patients had a family history of HCC. Three men were excessive drinkers, and one woman had a vertical HBV infection.

In conclusion, HBsAg seroclearance does not indicate safety out of HCC, particularly in patients with LC. Spontaneous HBsAg loss might occur in a large proportion of cryptogenic LC and HCC cases in Korea, and surveillance should be continued after HBsAg loss in the same manner as for HBsAg-positive patients. Sequential HBsAg-SCR data measured with the conventional test are very useful for the long-term management of carriers, similar to HBsAg levels.

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection follows a unique natural course, consisting of immune tolerance, eradication, and a recovery phase. Intricate changes in the balance between host and viral factors stimulate the phase transition. Prognosis of chronic carriers is determined by a complicated process with consideration of phase transition. Seroclearance of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is the final step of the recovery phase. However, the clinical features of HBsAg seroclearance have not yet been completely elucidated.

The recovery phase usually overlaps with the occurrence of escape mutations in the HBV genome and the development of liver cirrhosis (LC) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Thus, it is difficult to determine when and how the negative conversion of HBsAg (HBsAg-NC) has occurred to a sufficient extent to have preventive effects for HCC. The research hotspot is clarification of the clinical features associated with spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance, including the outcome and predictive markers, to facilitate the development of a patient management strategy both during and after the recovery phase.

The results of the present study have suggested that the phase transition to recovery occurs spontaneously in most patients and that asymptomatic LC is prevalent among these patients (31%). Thus, a significant proportion of chronic carriers are at risk of HCC at the time of recovery. In fact, the data showed that HCC developed among the patients with LC during the recovery phase both pre- and post-HBsAg seroclearance. On the other hand, it is known that the HBsAg quantity, in combination with the HBV DNA titer, is a predictive marker for HBsAg seroclearance. The authors have demonstrated for the first time that a signal-to-cutoff ratio of the qualitative HBsAg level (HBsAg-SCR) of < 1000 and its sequential decrease are notable predictive markers of HBsAg loss. Our data support the value of sequential HBsAg-SCR data.

The results of our study may facilitate the design of a management strategy for HBV carriers both pre- and post-HBsAg seroclearance. In particular, patients with evidence of chronic liver disease or LC should be carefully monitored for the development of HCC, even after the spontaneous loss of HBsAg.

Serum HBsAg positivity lasting for six months is a serological indicator for chronic HBV infection. HBsAg seroclearance refers to the spontaneous HBsAg-NC in the serum. The HBsAg-SCR is the signal-to-cutoff ratio of HBsAg, as measured by qualitative assay, and the quantification of HBV DNA and HBsAg (HBsAg-QNT) is the quantity of HBsAg in the serum, as measured by quantitative assay. The HBsAg-SCR is determined according to the signal intensity of an antigen-antibody reaction. The authors found that carriers with a very high HBV DNA titer of > 7 logs IU/mL exhibited a prozone effect, in which the HBsAg-SCR was paradoxically reduced by excess antigen. In contrast, in the HBV DNA-negative patients, an HBsAg-SCR < 1000 was strongly correlated with an HBsAg-QNT < 200 IU/mL. Otherwise, the HBsAg-SCR was not correlated with the HBsAg-QNT.

This invited manuscript written by Park et al investigated the clinical features of HBsAg serological clearance among almost 2000 Korean HBV carriers. This is a valuable study that included large-scale clinical sample analyses; the significant conclusion of this study is that liver cancer surveillance should be continued after HBsAg seroclearance, particularly in patients with cirrhosis. The title describes the contents of the paper. The abstract is informative and completely self-explanatory; it briefly presents the topic, states the scope of the experiments, provides the significant data, and notes the major findings and conclusions. The purpose or purported significance of the article is explicitly stated. The research study methods are complete enough to enable the experiments to be reproduced. All figures and tables are necessary and appropriate. The discussion interprets the findings in view of the results obtained in this and in past studies on this topic.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Zhu X S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Lee WM. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1733-1745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1728] [Cited by in RCA: 1712] [Article Influence: 61.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yuen MF, Lai CL. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15 Suppl:E20-E24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373:582-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 929] [Cited by in RCA: 992] [Article Influence: 62.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Shi YH, Shi CH. Molecular characteristics and stages of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3099-3105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Invernizzi F, Viganò M, Grossi G, Lampertico P. The prognosis and management of inactive HBV carriers. Liver Int. 2016;36 Suppl 1:100-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tseng TC, Liu CJ, Yang HC, Su TH, Wang CC, Chen CL, Kuo SF, Liu CH, Chen PJ, Chen DS. Determinants of spontaneous surface antigen loss in hepatitis B e antigen-negative patients with a low viral load. Hepatology. 2012;55:68-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tong MJ, Trieu J. Hepatitis B inactive carriers: clinical course and outcomes. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:311-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bae SH, Yoon SK, Jang JW, Kim CW, Nam SW, Choi JY, Kim BS, Park YM, Suzuki S, Sugauchi F. Hepatitis B virus genotype C prevails among chronic carriers of the virus in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20:816-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Jang JW, Chun JY, Park YM, Shin SK, Yoo W, Kim SO, Hong SP. Mutational complex genotype of the hepatitis B virus X /precore regions as a novel predictive marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:296-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Park YM, Jang JW, Yoo SH, Kim SH, Oh IM, Park SJ, Jang YS, Lee SJ. Combinations of eight key mutations in the X/preC region and genomic activity of hepatitis B virus are associated with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21:171-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Park YM. Clinical utility of complex mutations in the core promoter and proximal precore regions of the hepatitis B virus genome. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:113-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liaw YF. Hepatitis flares and hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion: implication in anti-hepatitis B virus therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:246-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yapali S, Talaat N, Fontana RJ, Oberhelman K, Lok AS. Outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis B who do not meet criteria for antiviral treatment at presentation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:193-201.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tong MJ, Nguyen MO, Tong LT, Blatt LM. Development of hepatocellular carcinoma after seroclearance of hepatitis B surface antigen. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:889-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Core Team R. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2015; Available from: http://www.R-project.org. |

| 16. | Fung J, Wong DK, Seto WK, Kopaniszen M, Lai CL, Yuen MF. Hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance: Relationship to hepatitis B e-antigen seroclearance and hepatitis B e-antigen-negative hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1764-1770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Moucari R, Marcellin P. [HBsAg seroclearance: prognostic value for the response to treatment and the long-term outcome]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34 Suppl 2:S119-S125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chu CM, Liaw YF. HBsAg seroclearance in asymptomatic carriers of high endemic areas: appreciably high rates during a long-term follow-up. Hepatology. 2007;45:1187-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lim TH, Gane E, Moyes C, Borman B, Cunningham C. HBsAg loss in a New Zealand community study with 28-year follow-up: rates, predictors and long-term outcomes. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:829-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kato Y, Nakao K, Hamasaki K, Kato H, Nakata K, Kusumoto Y, Eguchi K. Spontaneous loss of hepatitis B surface antigen in chronic carriers, based on a long-term follow-up study in Goto Islands, Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:201-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Han ZG, Qie ZH, Qiao WZ. HBsAg spontaneous seroclearance in a cohort of HBeAg-seronegative patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Med Virol. 2016;88:79-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lee CM, Chen CH, Lu SN, Tung HD, Chou WJ, Wang JH, Chen TM, Hung CH, Huang CC, Chen WJ. Prevalence and clinical implications of hepatitis B virus genotypes in southern Taiwan. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:95-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Arase Y, Suzuki F, Suzuki Y, Saitoh S, Kobayashi M, Akuta N, Someya T, Hosaka T, Sezaki H, Sato J. Long-term presence of HBV in the sera of chronic hepatitis B patients with HBsAg seroclearance. Intervirology. 2007;50:161-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Liu J, Lee MH, Batrla-Utermann R, Jen CL, Iloeje UH, Lu SN, Wang LY, You SL, Hsiao CK, Yang HI. A predictive scoring system for the seroclearance of HBsAg in HBeAg-seronegative chronic hepatitis B patients with genotype B or C infection. J Hepatol. 2013;58:853-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yu Y, Hou J, Omata M, Wang Y, Li L. Loss of HBsAg and antiviral treatment: from basics to clinical significance. Hepatol Int. 2014;8:39-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Seto WK, Wong DK, Fung J, Hung IF, Fong DY, Yuen JC, Tong T, Lai CL, Yuen MF. A large case-control study on the predictability of hepatitis B surface antigen levels three years before hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance. Hepatology. 2012;56:812-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yang SC, Lu SN, Lee CM, Hu TH, Wang JH, Hung CH, Changchien CS, Chen CH. Combining the HBsAg decline and HBV DNA levels predicts clinical outcomes in patients with spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion. Hepatol Int. 2013;7:489-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yuen MF, Wong DK, Fung J, Ip P, But D, Hung I, Lau K, Yuen JC, Lai CL. HBsAg Seroclearance in chronic hepatitis B in Asian patients: replicative level and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1192-1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lim TH, Gane E, Moyes C, Borman B, Cunningham C. Serological and clinical outcomes of horizontally transmitted chronic hepatitis B infection in New Zealand Māori: results from a 28-year follow-up study. Gut. 2015;64:966-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |