Published online Nov 7, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i41.9162

Peer-review started: June 21, 2016

First decision: July 12, 2016

Revised: August 1, 2016

Accepted: September 28, 2016

Article in press: September 28, 2016

Published online: November 7, 2016

Processing time: 141 Days and 14.9 Hours

To evaluate rebleeding, primary failure (PF) and mortality of patients in whom over-the-scope clips (OTSCs) were used as first-line and second-line endoscopic treatment (FLET, SLET) of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB, LGIB).

A retrospective analysis of a prospectively collected database identified all patients with UGIB and LGIB in a tertiary endoscopic referral center of the University of Freiburg, Germany, from 04-2012 to 05-2016 (n = 93) who underwent FLET and SLET with OTSCs. The complete Rockall risk scores were calculated from patients with UGIB. The scores were categorized as < or ≥ 7 and were compared with the original Rockall data. Differences between FLET and SLET were calculated. Univariate and multivariate analysis were performed to evaluate the factors that influenced rebleeding after OTSC placement.

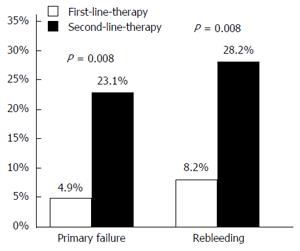

Primary hemostasis and clinical success of bleeding lesions (without rebleeding) was achieved in 88/100 (88%) and 78/100 (78%), respectively. PF was significantly lower when OTSCs were applied as FLET compared to SLET (4.9% vs 23%, P = 0.008). In multivariate analysis, patients who had OTSC placement as SLET had a significantly higher rebleeding risk compared to those who had FLET (OR 5.3; P = 0.008). Patients with Rockall risk scores ≥ 7 had a significantly higher in-hospital mortality compared to those with scores < 7 (35% vs 10%, P = 0.034). No significant differences were observed in patients with scores < or ≥ 7 in rebleeding and rebleeding-associated mortality.

Our data show for the first time that FLET with OTSC might be the best predictor to successfully prevent rebleeding of gastrointestinal bleeding compared to SLET. The type of treatment determines the success of primary hemostasis or primary failure.

Core tip: In the present study, the over-the-scope clip (OTSC) was evaluated for first-line and second-line endoscopic treatment (FLET, SLET) of high-risk upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. One hundred OTSCs were applied in 93 patients. Primary hemostasis and clinical success was achieved in 88% and 78%, respectively. Statistical analysis shows no significant influence of anticoagulants on the rebleeding rate. The total mortality was 21.5%. Primary failure was significantly reduced by the use of OTSC as FLET (4.9% vs 23.1%, P = 0.008). This largest single-center data of OTSC-placement in high-risk GI bleeding published to date shows, for the first time, that FLET is a significant predictor of reduced rebleeding (OR = 5.2; P = 0.009).

- Citation: Richter-Schrag HJ, Glatz T, Walker C, Fischer A, Thimme R. First-line endoscopic treatment with over-the-scope clips significantly improves the primary failure and rebleeding rates in high-risk gastrointestinal bleeding: A single-center experience with 100 cases. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(41): 9162-9171

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i41/9162.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i41.9162

Since the introduction of the Over-the-Scope Clip (OTSC®, Ovesco, Tübingen, Germany) in 2006 and the first clinical experience reported by Kirschniak et al[1] in 2007, the spectrum of indications has extended successively. Currently, the system, which is characterized by a circular tissue compression, is used for emergency endoscopy in acute gastrointestinal bleeding, acute perforation and fistula-closure in the upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) tracts. The reported success rates range between 42% and 100% depending on the indication[2,3].

Particularly with regard to reducing the high risk of undesirable outcomes, especially rebleeding and mortality, of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) secondary to peptic ulcer disease and other lesions, new endoscopic techniques such as the OTSC are increasingly the focus of interest.

Table 1 gives an overview of the last 9 years of experience with OTSC treatment of UGIB and lower non-variceal gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB)[3-16]. The data were processed to distinguish between first- and second-line endoscopic treatments (FLET/SLET).

| Ref. | n | Primary success (%) | Patients/clinical | Follow up, mean (mo) | Rebleeding, n | UGIB/LGIB, n | Design | |

| success (n/%) | ||||||||

| FLET | SLET | |||||||

| Wedi et al[4], 2016 | 44 | 85.4 | 31/? | 13/? | - | 6 | 41/3 | Single center |

| Retro | ||||||||

| Manno et al[3], 2015 | 40 | 100 | 40/100 | - | 1 | - | 40/0 | Single center |

| Retro | ||||||||

| Manta et al[5], 2013 | 30 | 97 | - | 93.3 | 1 | 2 | 23/7 | Multicenter |

| Retro | ||||||||

| Kirschniak et al[6], 2011 | 27 | 100 | 27/92.6 | - | 0.13 | 2 | 12/15 | Single center |

| Retro | ||||||||

| Skinner et al[7], 2014 | 12 | 100 | 12/83.4 | - | 1 | 2 | 12 | Single center |

| Retro | ||||||||

| Chan et al[8], 2013 | 9 | 100 | 3/100 | 6/77.7 | 2 | 2 | 9 | Single center |

| Pro | ||||||||

| Nishiyma et al[9], 2013 | 9 | 77.8 | 9/77.7 | - | 2.2 | 2 | 8/1 | Single center |

| Retro | ||||||||

| Baron et al[10], 2012 | 7 | 100 | - | 7/100 | 1 | 0 | 6/1 | Multicenter |

| Retro | ||||||||

| Albert et al[11], 2011 | 7 | 100 | - | 7/57 | 1 | 3 | 6/1 | Single center |

| Pro | ||||||||

| Repici et al[12], 2009 | 7 | 100 | 3/100 | 4/100 | 3 | 0 | 3/4 | Single center |

| Retro | ||||||||

| Mönkemüller et al[13], 2014 | 6 | 100 | - | 6/100 | 10 | 0 | 6 | Multicenter |

| Retro | ||||||||

| Alcaide et al[14], 2014 | 2 | 100 | - | 2/100 | - | - | 1/1 | Single center |

| Retro | ||||||||

| Jayaraman et al[15], 2013 | 2 | 100 | 2/100 | - | 2.9 | 0 | 0/2 | Single center |

| Retro | ||||||||

| Sulz et al[16], 2014 | 1 | 100 | 1/100 | - | - | 0 | 1 | Single center |

| Pro | ||||||||

Actually, the published data of OTSC in FLET and SLET are difficult to compare because of non-uniform and small sample sizes and the often insufficiently defined risk profiles of patients.

From recent results, four most important questions arise: (1) Are FLET and SLET with OTSC actually comparable in terms of outcomes? (2) Can any independent risk factors be defined with respect to the rate of rebleeding? (3) Do patients with UGIB and high Rockall risk scores (≥ 7) benefit from OTSC treatment with respect to morality compared to those with scores < 7? and (4) Is the outcome of OTSC in patients with UGIB comparable to the standard of care (conventional treatment modalities) regarding rebleeding events and rebleeding-associated mortality?

Consequently, the present single-center study retrospectively analyzed the outcome of FLET and SLET with OTSC in patients with UGIB and LGIB, to elicit differences in the quality and location of the bleeding lesions and the application of dual antiplatelet or anticoagulation drugs. In addition, patients with UGIB were categorized by complete Rockall risk score[17], and the data were used to calculate predictors of OTSC success and mortality.

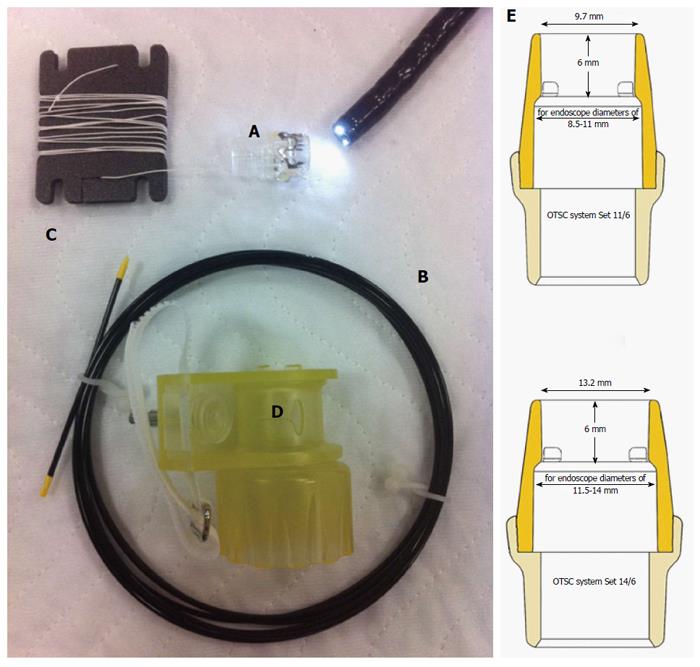

The OTSC device consists of a transparent applicator cap carrying the circular nitinol clip, a release thread, a hand wheel and a thread retriever. The applicator cap can be fixed on the distal end of the endoscope. The application mechanism is similar to common endoscopic variceal band-ligation systems. The clip application can be carried out after the tissue has been mobilized in the cap through grasping or suctioning (Figure 1). The compression force is 7-8 Newtons.

In our hospital, only the traumatic OTSC clip with sharp teeth is used in sizes of 11 and 14 mm diameter. The suction method was applied in all cases.

In this observational, single-center case series, the data of all patients with UGIB and LGIB who were treated with OTSC® (Ovesco Endoscopy GmbH, Tuebingen, Germany) between April 2012 and May 2016 were obtained from of our prospectively maintained database and retrospectively analyzed. The data were evaluated by patient demographics, indications, previous therapy and secondary treatments after failure of OTSC placement. The Rockall risk score was used to categorize patients with UGIB by risk of recurrent bleeding and mortality. Furthermore, we calculated total mortality, rebleeding events and rebleeding-associated mortality in patients with OTSC-treated UGIB compared to patients who received best standard-of-care (using the original Rockall data) based on a complete Rockall risk score < or ≥ 7. The same parameters were calculated from the original data published by Rockall and colleagues[17].

Written informed consent was obtained to the extent possible in emergency situations.

All procedures were performed with propofol sedation. OTSC was used primarily in cases of acute UGIB and recurrent UGIB after failure of conventional endoscopic therapies. The conventional treatment consisted of single-use or combinations such as epinephrine (1:10.000 dilution in saline)/fibrin glue (FG), epinephrine solution/through-the-scope clipping (TTSC) and thermal contact modalities such as argon plasma coagulation (APC). If recurrent bleeding was suspected during the subsequent hospital stay (hematemesis, melena, lack of increasing hemoglobin after transfusion, or a drop in hemoglobin of more than 2 g/dL within 24-h after transfusion or unclear or unstable cardiovascular parameters and shock), emergency endoscopy was performed. The procedures were performed by highly skilled endoscopists of our interdisciplinary team, using standard Olympus endoscopes (gastroscope GIF- H180J/XTQ160 and colonoscope CF-H180, Tokyo, Japan).

Independent of previous conventional treatments, the indication for OTSC placement was determined by the endoscopist in charge depending on the individual situation.

The following study endpoints were defined: (1) Primary hemostasis: No rebleeding immediately after OTSC placement; (2) Primary failure: Continued bleeding after OTSC placement; (3) Rebeeding: In-hospital rebleeding after primary hemostasis with OTSC; (4) Clinical success: Having no primary failure and no in hospital rebleeding; (5) Technical success: Successful placement of the OTSC on the target lesion; (6) Mortality (no rebleed): Mortality of patients without rebleeding after OTSC placement; (7) Mortality (rebleeding): Mortality of patients with continued bleeding or rebleeding after OTSC placement and rebleeding; and (8) Total Mortality: Total in-hospital mortality.

The number of OTSC clips used per patient was evaluated as well as adverse events due to the OTSC application. Secondary complications that had no effect on the primary result were not considered treatment failures.

The results of our study were obtained by retrospective analysis of our prospectively maintained database. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, (Version 23.0 Armonk, IBM Corp. NY, United States) was used for the statistical analysis. Categorical variables are given as absolute and relative frequencies; differences were evaluated by Fisher’s exact test. The Fisher exact test tends to be employed instead of Pearson’s chi-square test when sample sizes are small (calculation of the Freiburg vs the Rockall patient population, respectively). Univariate analysis was performed by using the χ2 test. Quantitative values are expressed as medians with interquartile range (IQR), and differences were measured using the Mann-Whitney-U-test or Kruskal-Wallis-test as appropriate. Multivariate logistic regression analysis with a forward stepwise selection strategy using a likelihood ratio, including the report of relative risks and their 95%CIs, was used to identify independent risk factors for rebleeding. The inclusion P for multivariate analysis was 0.10. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The null hypothesis asserts the independence of the variables under consideration.

A total of 93 patients [58 males, median age (IQR), 72 (19-98)] with 100 different severe acute UGIB and LGIB lesions were treated with OTSC as FLET or SLET. The types of bleeding lesions are shown in Table 2. One patient had 3 OTSC applications, and five other patients had 2 OTSCs on different lesions. Twenty-four patients were hospitalized primary due to an acute hemorrhage of the GI tract. The mean hospital stay was 19.8 d (range 1-79). Primary hemostasis and clinical success of UGIB and LGIB lesions was achieved in 88/100 (88%) and 78/100 (78%), respectively. An overview of the demographics, characteristics and OTSC results is given in Table 3.

| Lesions | FIa | FIb | FIIa | FIIb | Spurting | Oozing | Total | FLET | SLET |

| UGIB | (n = 69) | (n = 39) | (n = 33) | ||||||

| Ulcer | |||||||||

| Cardiac | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 3 | |||

| Gastric | 2 | 8 | 1 | 11 | 7 | 4 | |||

| Duodenal | 8 | 11 | 7 | 26 | 17 | 9 | |||

| Jejunal | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Polypectomy | |||||||||

| Gastric | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| Duodenal | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Anastomoses | 2 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| Gastrojejunal | |||||||||

| Mallory-Weiss | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Vascular Malformation | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Heart device | |||||||||

| Dieulafoy | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Metastasis | |||||||||

| Gastric | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| Lesions | FIa | FIb | FIIa | FIIb | Spurting | Oozing | Total | FLET | SLET |

| LGIB | (n = 31) | (n = 22) | (n = 9) | ||||||

| Ulcer | |||||||||

| Rectal | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 9 | 3 | ||

| Cecal | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Polypectomy | |||||||||

| Rectal | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Colonal | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | |||||

| Anastomoses | |||||||||

| Ileocolonic | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Hemorrhoidal | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Diverticular | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Tumor | |||||||||

| Colonic | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total (n = 93) | UGI (n = 63) | LGI (n = 30) | P value | |

| Sex, male | 58 (62) | 38 (60) | 20 (67) | 0.361 |

| Age (yr), median (IQR) | 72 (19-98) | 68 (27-92) | 74 (19-93) | 0.580 |

| Complete Rockall score, median (IQR) | - | 7 (3-10) | - | - |

| Anticoagulation | 46 (50) | 29 (46) | 17 (56) | 0.231 |

| In-Hospital-Mortality | 20 (22) | 17 (27) | 3 (10) | 0.051 |

| Lesions and clips | (n = 100) | (n = 69) | (n = 31) | |

| Bleeding source | ||||

| Ulcers | 66 | 50 (72) | 16 (52) | 0.018 |

| Other | 34 | 19 (27) | 15 (48) | |

| Active bleeding1 | 82 | 56 (81) | 26 (84) | 0.492 |

| First-line-therapy | 61 | 39 (57) | 22 (71) | 0.125 |

| Primary failure (including technical failure n = 2) | 12 | 8 (12) | 4 (13) | 0.545 |

| Rebleeding | ||||

| complete | 16 (16) | 11 (16) | 5 (16) | 0.597 |

In patients with SLET the median previous FG injection volume was 2.25 mL (1-8) (Tesseel 1 ml Duo S, Baxter, Unterschleißheim, Germany).

The median Rockall risk score of patients with UGIB was 7 (3-10; Table 4). No significant difference was observed between patients with a complete Rockall risk score < and ≥ 7 with respect to rebleeding (15% vs 19%, respectively, P = 0.51) and rebleeding-associated mortality (5% vs 14%, respectively, P = 0.27).

| Rockall risk score | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8+ | Total |

| n | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 13 | 13 | 30 | 63 |

Table 5 compares total mortality, rebleeding-associated mortality and rebleeding events of patients who received standard-of-care (the Rockall group) with patients who underwent OTSC treatment (the Freiburg group).Total mortality and rebleeding associated mortality were comparable in both groups, but patients with a high risk profile (≥ 7) had significantly fewer rebleeding events when treated with OTSC (original Rockall data group 46.8% vs Freiburg group 18.6%, P = 0.0003).

| Total mortality Rockall < 7 | Total mortality Rockall≥7 |

| Rockall1 5.8% vs Freiburg2 10%; P = 0.327 | Rockall 32.8% vs Freiburg 34.8%; P = 0.865 |

| 145 of 2499 vs 2 of 20 | 150 of 457 vs 15 of 43 |

| Rebleeding-associated mortality | Rebleeding-associated mortality |

| Rockall < 7 | Rockall ≥ 7 |

| Rockall 2.8% vs Freiburg 5%; P = 0.436 | Rockall 22.3% vs Freiburg 13.9%; P = 0.247 |

| 70 of 2499 vs 1 of 20 | 102 of 355 vs 6 of 43 |

| Rebleeding events Rockall < 7 | Rebleeding events Rockall ≥ 7 |

| Rockall 13.8% vs Freiburg 15%; P = 0.750 | Rockall 46.8% vs Freiburg 18.6%; P = 0.0003 |

| 345 of 2499 vs 3 of 20 | 214 of 457 vs 8 of 43 |

In univariate analysis, type of lesion, location (UGIB, LGIB), bleeding activity (active, non-active) and anticoagulants were not statistically significant predictors for rebleeding (Table 6). However, our data shows that the clinical success of patients with both UGIB and LGIB was significantly higher when OTSCs were applied as FLET compared to SLET (8.2% vs 28.2%, P = 0.009, Figure 2). In multivariate analysis, compared to SLET, only FLET continued to be a significant factor related to reduced rebleeding (OR = 5.2; P = 0.009).

| Predictor | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| OR (CI) | P value | OR (CI) | P value | |

| Bleeding (active/non active) | 0.94 (0.24-3.72) | 0.586 | 1.43 (0.33-6.21) | 0.636 |

| Localization (UGIB/LGIB) | 0.99 (0.31-3.13) | 0.597 | 1.67 (0.45-6.15) | 0.451 |

| Anticoagulation (Y/N) | 1.41 (0.48-4.15) | 0.359 | 1.34 (0.43-4.20) | 0.611 |

| Lesion (ulcers/others) | 1.65 (0.53-5.17) | 0.282 | 2.03 (0.56-7.27) | 0.275 |

| Treatment (SLET/FLET) | 4.40 (1.39-13.90) | 0.009 | 5.29 (1.53-18.24) | 0.008 |

Primary failure was significantly reduced by the use of OTSC placement as FLET (4.9% vs 23.1%, P = 0.008, Figure 2). In one patient with a posterior duodenal wall ulcer, over 50% of the circumference the tissue was so strongly indurated that the clip could not grasp the tissue (technical failure). The same phenomenon was observed with an ileo-transversostomy anastomosis, during which the clip bounced off, and which was treated with multiple adrenalin injections. No malfunction of the device was registered. One adverse event was observed 1.8 mo after a duodenal OTSC application. The resulting lumen obstruction was released with 3 balloon-dilatations.

In total, 47 patients (50%) had no anticoagulants. Nine (10%) patients were treated with one platelet aggregation inhibitor, and 40 patients had anticoagulants (43%) with or without one or more antiplatelet drugs.

Statistical analysis showed no significant influence of anticoagulants on the rebleeding rate after OTSC placement (Table 6).

The total mortality was 21.5%. Causes of death included respiratory insufficiency (n = 3), cardiogenic shock (n = 2), stroke (n = 3), hemorrhagic shock (n = 4), multi-organ failure and septic shock (n = 8).

Two patients died during the hemostasis. One of them died due to a cardiogenic shock during endoscopic clip application and the other due to an aeroembolism after radiological embolization of the gastroduodenal artery.

The in-hospital mortality of patients with UGIB and a complete Rockall risk score of ≥ 7 was significant higher compared to that of those with scores < 7 (35% vs 10%, P = 0.034). The mortality rate of patients with UGIB without rebleeding and rebleeding-associated mortality was 15.9% and 11%, respectively.

Acute gastrointestinal bleeding is a common and potentially life-threatening emergency with an wide-ranging annual incidence of hospitalization of 42-172 and 20-87 per 100000 for upper and lower GI tract, respectively, and it has a mortality rate as high as 10%[17-26].

In the last 10 years, the experience with OTSC to treat high-risk non-variceal bleeding (NVGIB) of the upper and lower GI tract remains limited, and the published data include small-case series[3-16].

Especially for new technologies, the question arises whether their effectiveness is comparable to established endoscopic techniques, in particular to avoid rebleeding and perhaps to reduce rebleeding-associated mortality in multimorbid patients.

To the best of our knowledge, we present the largest single-center study of OTSCs to date to differentiate FLET and SLET techniques in the management of acute GI bleeding. The data of this series are the first to provide the following answers to important questions with respect to the application and performance of the new device:

First, FLET and SLET are not comparable with respect to the prevention of rebleeding. Importantly, primary failure was attained significantly more in the SLET group of patients compared with FLET patients and in particular if the GI bleeding was pretreated with FG. In these patients, a mean volume-injection of 2.25 portions of FG was administered. Moreover, some underwent APC, and previously applied TTSC had to be removed before OTSC placement. The resulting alterations of the tissue (hardening and fibrosis) can disguise the bleeding source of the target lesion and therefore make the identification difficult. Additionally, the tissue cannot be (or at least not sufficiently) suctioned into the applicator cap, which can cause primary and technical failure. Other authors have reported similar experiences.

A decreased clinical success was observed by OTSC rescue therapy due to the fibrotic nature of leaks and fistulae[2,27,28], and primary therapy was found to be a significant predictor for clinical success of defect closures. In this context, Baron et al[28] postulated the use of an anchoring device (Ovesco Endoscopy AG, Tübingen, Germany) could be helpful.

Second, our data show that type of treatment (FLET vs SLET) is an independent predictor to prevent rebleeding.

Previous studies have identified a first and second bleeding endoscopic failure rate of 16% and 33.3%, respectively. Furthermore, unsuccessful endoscopic hemostasis was found to be an independent risk factor for rebleeding and was associated with increased 30-d mortality in patients with NVGIB[17,29,30]. These findings support the role of a primary effective endoscopic hemostasis.

In multivariate analysis, OTSCs performed significantly better across all GI bleeding types (UGIB, LGIB) when applied as FLET as opposed to rescue therapy (SLET).

Thus, according to our experience, the use of the OTSC device is preferable in active bleeding from lesions of visible vessels and ulcers, which have never been treated previously with conventional endoscopic treatments, and which are equal to or less than 3 cm in diameter. Less preferable is its use in diffuse bleeding from polypoid metastases, vascular malformations and hardened and fibrotic lesions.

Third, our data suggest that patients with UGIB and a complete Rockall risk score ≥ 7 might not benefit from OTSC treatment compared to patients with score values of < 7. The total mortality rates of patients with Rockall scores < vs≥ 7 in the current study are in accordance with those from a prior large, multicenter series published by Rockall et al[17]. Furthermore, no significant differences were observed in relation to the rebleeding rate and rebleeding-associated mortality in both groups (< 7 vs≥ 7) treated with OTSC.

Fourth, based on the original Rockall data, patients with UGIB and complete Rockall risk scores ≥ 7 could benefit from OTSC placement with respect to the reduction of rebleeding events, compared to endoscopic established treatment modalities. The mortality remains unaffected.

Currently, there are no published prospective trials regarding the use of OTSC for endoscopic hemostasis compared to conventional techniques.

Indeed, established interventions, including FG, TTSC, band ligators, thermal modalities alone or in combination with epinephrine solution or recently commercially introduced hemostatic granules or powders, show a wide range of permanent hemostasis varying from 10%to 85%[31-35]. However, combined modalities such as hemoclip and injection therapy or thermal coagulation and injection therapy appear to be superior to the use of injection or thermal techniques alone[36].

Therefore, it is generally difficult to compare the outcome of OTSC with previously published data of established endoscopic techniques regarding the reduction of undesirable outcomes of UGIB and LGIB, including rebleeding and mortality and independent of GI localization and bleeding activity.

For this reason, we calculated total mortality, rebleeding events and rebleeding-associated mortality in relation to patients with Rockall scores < or ≥ 7 of both the OTSC and original Rockall sample sizes. However, no differences in patients with Rockall scores < 7 were observed with respect to above-mentioned parameters. Only in patients with Rockall scores ≥ 7 were the rebleeding events significant reduced compared to the calculated original Rockall data, which might indicates a selection bias because our collective mainly consisted of predominantly spurting and oozing bleeding lesions. Prospective randomized trials are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Finally, durability and exact placement of hemostatic clips on the bleeding source are important factors for successful hemostasis and to reduce rebleeding, other adverse events and emergency surgery.

Modern TTS clips for example can be rotated and reopened, and they open at a wide angle. However, TTSCs have several disadvantages:

It is commonly known that more than one TTSC is necessary for the treatment of large bleeding lesions or blood vessels with large diameters because a single clip can only compress small tissue areas. In addition, adequate space is required properly to release the TTSC. That is why TTSC release in angulated positions such as the duodenum can be tricky.

Due to this and our results, and considering the costs of modern single-use TTS clip systems, we strive for a paradigm shift. Thus, in patients with circumscribed lesions of high-risk UGIB and LGIB, we employ OTSC as FLET.

On the other hand, it is important to understand the mechanism of the OTSC device. The degree of mobilization of the tissue into the applicator cap is crucial for therapeutic success. For patients who require an endoscopic full-thickness resection (FTRD), for example, a similar problem exists. In these cases, we identify the target tissue to resect and mobilize this tissue using a specially designed cap (FTRD prOVE Cap, Ovesco Endoscopy AG, Tübingen, Germany)[37].

Certainly, our study has some limitations, e.g., its retrospective nature. Moreover, only experienced endoscopists with a high level of expertise performed the procedures with the OTSC device. Nevertheless, the present study also has many strengths. It is a large, single-center study with a broad spectrum of bleeding lesions in the upper and lower GI tracts. The large number of lesions, most of which were characterized by a spurting and oozing quality, were treated only with the suction method, and the traumatic type of OTSC represents a homogeneous study cohort that allowed, for the first time, statistically substantiated hypotheses on the effectiveness of the OTSC-device.

In conclusion, the reduction of primary failure was best achieved in patients undergoing treatment of UGIB and LGIB when OTSC was used for FLET. In our series, FLET seems to be a predictor of successful reduction of rebleeding rates.

We acknowledge Novineon CRO and Consulting Ltd. and Mr. Weiland for their consulting support of the statistics.

Over-the-scope clips (OTSC) are used for emergency endoscopy in acute perforation and fistula-closure in the upper and lower GI tracts. Furthermore, the OTSCs have become an important tool in hemostasis of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB, LGIB) as first-line and second-line endoscopic treatment (FLET, SLET). However, direct comparisons of OTSCs in FLET and SLET are limited.

In this retrospective analysis of 93 patients, the authors compared the results of first-line and second-line endoscopic treatment of 100 OTS clips in UGIB and LGIB. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest single-center series on the use of OTSCs in GI bleeding to date.

Primary failure and rebleeding occurred significantly more often in patients undergoing second-line endoscopic treatment with OTSC than in first-line treated patients. The better outcome of first-line treated patients is comparable with the known data in patients with fistula, who were treated with OTSC.

By understanding the mechanism, advantages and limits of the OTSCs device, the present study might provide a new prognostic factor for clinical success and hemostatic treatment of acute GI bleeds treated with OTSCs as first-line therapy.

The manuscript presents the outcome of first- and second-line endoscopic treatment with OTSC in high risk gastrointestinal bleeding. It is a topic of interest to the researchers in the related areas but the paper needs some improvement before acceptance for publication.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: He B, Reinehr R S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Kirschniak A, Kratt T, Stüker D, Braun A, Schurr MO, Königsrainer A. A new endoscopic over-the-scope clip system for treatment of lesions and bleeding in the GI tract: first clinical experiences. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:162-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Haito-Chavez Y, Law JK, Kratt T, Arezzo A, Verra M, Morino M, Sharaiha RZ, Poley JW, Kahaleh M, Thompson CC. International multicenter experience with an over-the-scope clipping device for endoscopic management of GI defects (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:610-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Manno M, Mangiafico S, Caruso A, Barbera C, Bertani H, Mirante VG, Pigò F, Amardeep K, Conigliaro R. First-line endoscopic treatment with OTSC in patients with high-risk non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: preliminary experience in 40 cases. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2026-2029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wedi E, Gonzalez S, Menke D, Kruse E, Matthes K, Hochberger J. One hundred and one over-the-scope-clip applications for severe gastrointestinal bleeding, leaks and fistulas. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1844-1853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Manta R, Galloro G, Mangiavillano B, Conigliaro R, Pasquale L, Arezzo A, Masci E, Bassotti G, Frazzoni M. Over-the-scope clip (OTSC) represents an effective endoscopic treatment for acute GI bleeding after failure of conventional techniques. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3162-3164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kirschniak A, Subotova N, Zieker D, Königsrainer A, Kratt T. The Over-The-Scope Clip (OTSC) for the treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding, perforations, and fistulas. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2901-2905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Skinner M, Gutierrez JP, Neumann H, Wilcox CM, Burski C, Mönkemüller K. Over-the-scope clip placement is effective rescue therapy for severe acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endosc Int Open. 2014;2:E37-E40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chan SM, Chiu PW, Teoh AY, Lau JY. Use of the Over-The-Scope Clip for treatment of refractory upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a case series. Endoscopy. 2014;46:428-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nishiyama N, Mori H, Kobara H, Rafiq K, Fujihara S, Kobayashi M, Oryu M, Masaki T. Efficacy and safety of over-the-scope clip: including complications after endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2752-2760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Baron TH, Wong Kee Song LM. Placement of an esophageal self-expandable metal stent through a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tract, for endoscopic therapy of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 2 UCTN:E319-E320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Albert JG, Friedrich-Rust M, Woeste G, Strey C, Bechstein WO, Zeuzem S, Sarrazin C. Benefit of a clipping device in use in intestinal bleeding and intestinal leakage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:389-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Repici A, Arezzo A, De Caro G, Morino M, Pagano N, Rando G, Romeo F, Del Conte G, Danese S, Malesci A. Clinical experience with a new endoscopic over-the-scope clip system for use in the GI tract. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:406-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mönkemüller K, Peter S, Toshniwal J, Popa D, Zabielski M, Stahl RD, Ramesh J, Wilcox CM. Multipurpose use of the ‘bear claw’ (over-the-scope-clip system) to treat endoluminal gastrointestinal disorders. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:350-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Alcaide N, Peñas-Herrero I, Sancho-del-Val L, Ruiz-Zorrilla R, Barrio J, Pérez-Miranda M. Ovesco system for treatment of postpolypectomy bleeding after failure of conventional treatment. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2014;106:55-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jayaraman V, Hammerle C, Lo SK, Jamil L, Gupta K. Clinical Application and Outcomes of Over the Scope Clip Device: Initial US Experience in Humans. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2013;2013:381873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sulz MC, Bertolini R, Frei R, Semadeni GM, Borovicka J, Meyenberger C. Multipurpose use of the over-the-scope-clip system (“Bear claw”) in the gastrointestinal tract: Swiss experience in a tertiary center. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16287-16292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38:316-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 888] [Cited by in RCA: 895] [Article Influence: 30.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Quan S, Frolkis A, Milne K, Molodecky N, Yang H, Dixon E, Ball CG, Myers RP, Ghosh S, Hilsden R. Upper-gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to peptic ulcer disease: incidence and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17568-17577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 19. | Blatchford O, Davidson LA, Murray WR, Blatchford M, Pell J. Acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in west of Scotland: case ascertainment study. BMJ. 1997;315:510-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Button LA, Roberts SE, Evans PA, Goldacre MJ, Akbari A, Dsilva R, Macey S, Williams JG. Hospitalized incidence and case fatality for upper gastrointestinal bleeding from 1999 to 2007: a record linkage study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:64-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EA, Geraedts AA, Tijssen JG, Reitsma JB, Tytgat GN. Acute upper GI bleeding: did anything change? Time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1494-1499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 347] [Cited by in RCA: 365] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 22. | Longstreth GF. Epidemiology and outcome of patients hospitalized with acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:419-424. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Lanas A, García-Rodríguez LA, Polo-Tomás M, Ponce M, Alonso-Abreu I, Perez-Aisa MA, Perez-Gisbert J, Bujanda L, Castro M, Muñoz M. Time trends and impact of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation in clinical practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1633-1641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 454] [Cited by in RCA: 414] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hreinsson JP, Gumundsson S, Kalaitzakis E, Björnsson ES. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding: incidence, etiology, and outcomes in a population-based setting. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:37-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Ahsberg K, Höglund P, Kim WH, von Holstein CS. Impact of aspirin, NSAIDs, warfarin, corticosteroids and SSRIs on the site and outcome of non-variceal upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1404-1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Laine L, Yang H, Chang SC, Datto C. Trends for incidence of hospitalization and death due to GI complications in the United States from 2001 to 2009. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1190-115; quiz 1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Schmidt A, Bauerfeind P, Gubler C, Damm M, Bauder M, Caca K. Endoscopic full-thickness resection in the colorectum with a novel over-the-scope device: first experience. Endoscopy. 2015;47:719-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Baron TH, Song LM, Ross A, Tokar JL, Irani S, Kozarek RA. Use of an over-the-scope clipping device: multicenter retrospective results of the first U.S. experience (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:202-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Han YJ, Cha JM, Park JH, Jeon JW, Shin HP, Joo KR, Lee JI. Successful Endoscopic Hemostasis Is a Protective Factor for Rebleeding and Mortality in Patients with Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:2011-2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ogasawara N, Mizuno M, Masui R, Kondo Y, Yamaguchi Y, Yanamoto K, Noda H, Okaniwa N, Sasaki M, Kasugai K. Predictive factors for intractability to endoscopic hemostasis in the treatment of bleeding gastroduodenal peptic ulcers in Japanese patients. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:162-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Rutgeerts P, Rauws E, Wara P, Swain P, Hoos A, Solleder E, Halttunen J, Dobrilla G, Richter G, Prassler R. Randomised trial of single and repeated fibrin glue compared with injection of polidocanol in treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer. Lancet. 1997;350:692-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lin HJ, Hsieh YH, Tseng GY, Perng CL, Chang FY, Lee SD. A prospective, randomized trial of endoscopic hemoclip versus heater probe thermocoagulation for peptic ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2250-2254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Wong Kee Song LM, Banerjee S, Barth BA, Bhat Y, Desilets D, Gottlieb KT, Maple JT, Pfau PR, Pleskow DK, Siddiqui UD. Emerging technologies for endoscopic hemostasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:933-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Pasha SF, Shergill A, Acosta RD, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Early D, Evans JA, Fisher D, Fonkalsrud L, Hwang JH. The role of endoscopy in the patient with lower GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:875-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Goelder SK, Brueckner J, Messmann H. Endoscopic hemostasis state of the art - Nonvariceal bleeding. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;8:205-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 36. | Baracat F, Moura E, Bernardo W, Pu LZ, Mendonça E, Moura D, Baracat R, Ide E. Endoscopic hemostasis for peptic ulcer bleeding: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2155-2168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Richter-Schrag HJ, Walker C, Thimme R, Fischer A. [Full thickness resection device (FTRD). Experience and outcome for benign neoplasms of the rectum and colon]. Chirurg. 2016;87:316-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |