Published online Oct 7, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i37.8398

Peer-review started: June 1, 2016

First decision: July 12, 2016

Revised: July 19, 2016

Accepted: August 10, 2016

Article in press: August 10, 2016

Published online: October 7, 2016

Processing time: 121 Days and 18.9 Hours

To evaluate the feasibility of side-to-side anastomosis of the lesser curvature of stomach and jejunum in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB).

Seventy-seven patients received side-to-side anastomosis of the lesser curvature of stomach and jejunum by utilization of linear stapler in LRYGB from April 2012 to July 2015 were retrospectively analyzed.

All patients were successfully completed laparoscopic gastric bypass with the side-to-side anastomosis of the lesser curvature of stomach and jejunum. No patient was switched to laparotomy during operation. No early complications including gastrointestinal anastomotic bleeding, fistula, obstruction, deep vein thrombosis, incision infections, intra-abdominal hernia complications were found. One patient complicated with stricture of gastrojejunal anastomosis (1.3%) and six patients complicated with incomplete intestinal obstruction (7.8%). BMI and HbA1c determined at 3, 6, 12, 24 mo during follow up period were significantly reduced compared with preoperative baselines respectively. The percentage of patients who maintain HbA1c (%) < 6.5% without taking antidiabetic drugs reached to 61.0%, 63.6%, 75.0%, and 63.6% respectively. The outcome parameters of concomitant diseases were significantly improved too.

Present surgery is a safety and feasibility procedure. It is effective to lighten the body weight of patients and improve type 2 diabetes and related complications.

Core tip: Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) has been widely applied in the treatment of obesity patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Gastrojejunostomy is one of the most important procedures in LRYGB. However, the surgical mode has not been standardized. We have proved in this study that the modified side to side anastomosis of the lesser curvature of stomach and jejunum applied with linear cutting closer in LRYGB is a safe, feasible, and effective therapeutic option in the treatment of obesity patients with type 2 diabetes and complications, which could make gastrojejunostomy standardized easily in LRYGB.

- Citation: Bai RX, Yan WM, Li YG, Xu J, Zhong ZQ, Yan M. Application of side-to-side anastomosis of the lesser curvature of stomach and jejunum in gastric bypass. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(37): 8398-8405

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i37/8398.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i37.8398

With the increasing incidence of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), bariatric surgery has becoming more and more popular as a therapeutic option. At present time, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) is generally applied in the treatment of obesity patient with T2DM. Following 20 years clinical practice, the advantages of this surgery in aspects of curative effectiveness, weight loss, diabetes control and safety are gradually recognized worldwide and has become a gold standard mode for patients indicated[1]. LRYGB procedure mainly contains 3 processes including gastric pouch formation, gastrojejunostomy and jejunojejunostomy. Wherein, gastrojejunostomy is the most critical step because it needs proficient and skilled surgeon to control the size of anastomosis, which is usually associated with the occurrence of complications. Currently, the diverse surgical techniques applied for anastomosis in LRYGB are circular-stapled gastrojejunostomy (43%), linear-stapled gastrojejunostomy (41%), and full hand-sewn (21%) gastrojejunostomy individually[2].

The circular-stapled gastrojejunostomy was first described by Wittgrove in 1994. It possesses the characteristic of easy size control of anastomosis. However, this surgical mode demands prolonged length of operation time because it is difficult to insert a stapling anvil block inside the gastric pouch and hardly find the active bleeding spot at anastomotic site[3]. Although the technique of full hand-sewn gastrojejunostomy was first reported by Higa et al[4], it was not expediently accepted by surgeons due to the requirement of longer learning curve and stronger laparoscopic suture skill. Schauer et al[5] first introduced the linear-stapled gastrojejunostomy in LRYGB, which triumphed over the complexity of stapling anvil block placement in circular-stapled gastrojejunostomy and improved the management of anastomosis bleeding.

Since irregular and unsmooth anastomotic suture will produce the stricture of anastomosis, it requires more professional and skillful surgeon to perform the surgery. However, no matter what mode of anastomosis is selected, certain rate of complications related to gastrointestinal anastomosis will still happen after surgery, for instance, the rate of fistula is 0.93%-6%, stenosis is 1.6%- 6.41%, and bleeding is 0%-1.75%[3-16].

Torres et al[17] considered that the anastomosis of Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy from the lesser curvature could bring on the food continuous through the anastomostic stoma and effectively moderate the gastric pouch expansion after surgery. We, therefore, take the linear stapler instead of Torres’ circular stapler to improve the gastrojejunostomy in lesser curvature of stomach and close the anastomosis.

The purpose of this study is to investigate the safety and feasibility of modified LRYGB and its impact on perioperative complications and the resolutions of T2DM.

All data of consective 82 obese patients with T2DM (diagnosed according to the China Diabetes Association guidelines[18]) undergoing LRYGB at the general surgery department of Beijing Tian Tan Hospital from April 2012 to July 2015 were retrospectively reviewed. Among them, 5 patients were excluded because of incomplete data collection. Thus, 77 patients in total were qualified to enter the study finally. The patients included 46 women and 31 men with a mean age of 46 years (range 19-67), a mean body mass index (BMI) 32.1 kg/m2 (range 27.7-51.4), a mean glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) 8.3% (range 5.5%-13.3%) and a mean T2DM duration 7 years (range 1-25), respectively. In addition, 29 patients showed hypertension, 31 patients showed fatty liver and 38 patients showed abnormal lipid metabolism (Table 1). The average follow-up period was 16.5 ± 9.4 mo (range 6-39 mo). The number of patients who completed postoperative follow-up at 12, 24, 36 mo was 56 cases (72.7%), 33 cases (42.9%) and 6 cases (7.8%) correspondingly.

| Characteristic | |

| Gender (n) | |

| Men | 46 |

| Women | 31 |

| Age (yr) | 46 ± 11 (19-67) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.1 ± 4.9 (27.7-51.4) |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.3 ± 1.6 (5.5-13.3) |

| Mean T2DM duration(yr) | 7 ± 5 (1-25) |

| Concomitant disorder (n) | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 38 |

| Fatty liver | 31 |

| Hypertension | 29 |

| Follow-upduration (n) | |

| 6 mo | 77 |

| 12 mo | 56 |

| 24 mo | 33 |

| 36 mo | 6 |

The patient was placed in a dorsal elevated position on surgical table and the legs were separated to allow the surgeon standing between them. A 10-mm trocar was inserted through a periumbilical port for developing a pneumoperitoneum and laparoscopic guidance. Two pieces of 13-mm trocar were inserted separately at the left/right points above umbilicus. Two pieces of 5-mm trocars were inserted at subxiphoid (for liver retractor) and left subcostal position, seperately. The distance between each trocar should be over 6-7 cm for avoiding interference each other. The intra-abdominal pressure should be maintained constantly at 13 mmHg.

The liver was retracted by a laparoscopic forceps through subxiphoid port. The esophagus was exposed and the cardia-esophageal junction and angle of His were identified.

The isolating dissection began at the lesser curvature of stomach by harmonic scalpel from 9 to 4 cm below the cardia approximately. The stomach was elevated and an aperture was created adjacent to the posterior gastric wall and around the lesser curvature. The dissection started at the lesser curvature from 9 cm below the cardia approximately. The LLC Echelon 60 endopath stapler -1.5 mm (ETHICON ENDO-SURGERY) was then applied initially in an inclined direction (near 45° angle of lesser curvature). The dissection was continued from the lesser curvature about 2.5-3.0 cm and the direction of the transaction line was turned vertically, aiming to the angle of His. The pouch should be oriented vertically and the width was near 2.5-3.0 cm. Four or five times repeated of the Echelon 60 endopath stapler -1.5 mm were required to completely divide the stomach.

The harmonic scalpel was implemented for tissue separation along with the intestinal wall distal to the ligament of Trietz about 100 cm, range from approximately 5 cm distally. The distal jejunum was then grasped by atraumatic laparoscopic forceps and brought up to the gastric pouch in front of the colon.

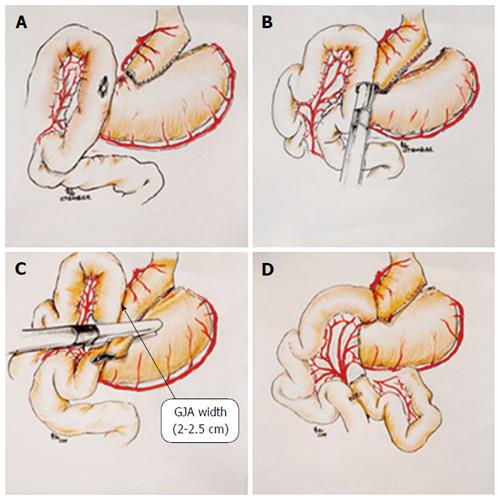

A stab wound was made on the end of lesser curvature of the gastric pouch and on the wall of the jejunum contra of the mesentery with laparoscopic coagulation hook separately (Figure 1A). A blade of the Echelon 60 endopath stapler -1.5 mm was inserted through the stab wound of the distal jejunum. The other blade of the linear stapler was placed into the gastric pouch, and the lesser curvature of the gastric pouch is anastomosed to the jejunum side-to-side with the stapler (Figure 1B). The staple lines were inspected for bleeding under laparoscopic vision. The common open of stomach and jejunal loop were clamped together with the linear staplers (Echelon 60 endopath stapler -1.2 mm and Echelon 60 endopath stapler -1.5 mm) after staunching the bleeding of the staple line, insuring the width of gastrointestinal anastomosis attaining 2.5 cm or so (nearly 25 mm circular stapler) (Figure 1C). The side-to-side anastomosis between the gastric pouch and jejunum was then completed.

A stab wound made with laparoscopic coagulation hook on the wall of the jejunum contra of the mesentery, near 100 cm distal to the gastrojejunostomy (alimentary limb were varied in length depend on preoperative BMI of the patient (such as 100 cm length for patient BMI ≤ 50 kg/m2, 120 cm length for patient BMI > 50 kg/m2), the proximal loop of the jejunum brought down to the site of the stab wound, the proximal loop and distal segment of the jejunum was anastomosed side-to-side with the Echelon 60 endopath stapler -1.2 mm. Another Echelon 60 endopath stapler -1.2 mm was used to close the opening of the jejunum after staunching the bleeding of the staple line to complete the Roux-en-Y anastomosis surgery (Figure 1D). A drain tube was placed on the left side of cardia and washed the abdominal cavity by saline without the bleeding of gastrointestinal and intestinal anastomosis.

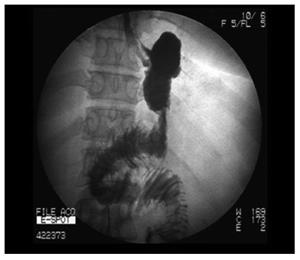

No patient was employed the nasogastric suction postoperatively. All patients were taken the gastrointestinal contrast radiograph with ioversol (iodic contrast agent) on the third day morning after surgery. Figure 2 showed a typical appearance of gastric pouch. Patients were allowed to ingest the liquid food to ensure the anastomotic stoma without leakage. Most patients were ready for discharge on the 4th-6th postoperative day.

Patients were prescribed to take proton pump inhibitors orally, and instructed to supplement consistently of multivitamins and trace elements for a long period. The follow up visits for patients were scheduled at 1st, 3rd, 6th and 12th mo respectively after surgery in the first year, and twice a year thereafter.

Complication is defined as a major event happening and requiring intervention during or after procedure. T2DM remission is defined by the laboratory test of fasting glucose level < 100 mg/dL, HbA1c < 6.5% and an unwillingness to pursue medical treatment.

Patients data were collected and registered into the database of bariatric center, including the parameters of patients demographics, BMI, weight loss, length of hospital stay, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), complications, and comorbidit (hyperlipidemia, fatty liver, hypertension).

Patients body weight was measured in light clothing without shoes to the nearest 0.1 kg, and body height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Blood was drawn for laboratory examination from an antecubital vein following an overnight fast. Measurements were acquired using the Hitachi 7170 and J&J nephelometer assay (Dade Behring, United States). The serum insulin and C-peptide levels were measured using a DPC Immulite analyzer. All specimens were processed within 1 h of collection. Informed consent from the patients and ethics approval from the Institutional Research Ethics Committee was obtained.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 16.0, with a baseline comparison by t tests, one-way ANOVA and chi-square tests. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± SD. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

All patients were successfully completed whole LRYGB procedure. Among them, 9 patients experienced concomitant cholecystectomy. Nobody was switched to the laparotomy surgery. The patients were followed up for 6-39 mo. The average operative time was 2.6 ± 0.8 (1.5-5.8) h, blood loss was 58.4 ± 31.1 (10-200) mL, and the length of postoperative hospital stay was 5.9 ± 1.4 (4-14) d.

Nobody was dead. One patient (1.3%) required secondary surgery because of bleeding of side-to-side anastomosis between intestinal 34 h after first surgery. No patient occurred the complications of gastrointestinal anastomotic bleeding, fistula, obstruction, deep vein thrombosis, incision infections, intra-abdominal hernia and any others during early stage after surgery (< 30 d).

One patient (1.3%) was carried out the repeated laparoscopic operation ascribe to the stricture of gastrojejunal anastomosis 6 mo later following first surgery. The patient presented the symptoms and signs of anastomosis stenosis 6 wk after surgery and failed to endoscopic dilation management. Six patients (7.8%) arose the incomplete intestinal obstructions, and were treated conservatively by bowel rest and parenteral nutrition. Iron deficiency anemia was appeared in two patients (2.6%) at 9 and 18 mo after operation, and was treated by ferrous preparation. One patient (1.3%) showed upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage associated with oral aspirin intake. One patient (1.3%) developed acute pancreatitis 22 mo after surgery and was treated by medications. In addition, five patients (7.6%) were newly diagnosed as cholelithiasis in 66 patients after surgery. Nine and two patients were individually experienced cholecystectomy during or before LRYGB (Table 2).

| Complications | n (%) |

| Early complications (< 30 p-o d) | |

| JJA bleeding | 1 (1.3) |

| Late complications (> 30 p-o d) | |

| GJA stenosis | 1 (1.3) |

| Intestinal obstruction | 6 (7.8) |

| Iron deficiency anemia | 2 (2.6) |

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 (1.3) |

| Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 1 (1.3) |

| Gallstones | 5 (7.6) |

| Total | 17 (23.2) |

Fifty-six patients (72.7%) were followed up for 12 mo and 33 patients (42.9%) were followed up for 24 mo after surgery. BMI and HbA1c determined at 3, 6, 12, 24 mo during following up period after surgery were significantly reduced compared with those before operation respectively (Table 3). BMI achieved to minimal level at 1 year after surgery.

| Follow-up | Pre-op. | 3 mo Post-op. | 6 mo Post-op. | 12 mo Post-op. | 24 mo Post-op. | F value | P value | |

| 12 mo (n = 56) | BMI (kg/m2) | 32.3 ± 5.0 | 26.6 ± 4.5 | 25.3 ± 4.1 | 24.9 ± 4.0 | / | 33.738 | 0.000 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.1 ± 1.6 | 6.2 ± 1.0 | 5.7 ± 0.6 | 6.1 ± 1.1 | / | 47.506 | 0.000 | |

| 24 mo (n = 33) | BMI (kg/m2) | 31.2 ± 3.5 | 25.8 ± 3.5 | 24.3 ± 3.1 | 24.0 ± 2.9 | 24.4 ± 2.9 | 29.550 | 0.000 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.5 ± 1.7 | 6.2 ± 0.9 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 5.7 ± 0.6 | 6.2 ± 1.0 | 41.135 | 0.000 | |

The portions of patients who maintained HbA1c (%) < 6.5% without antidiabetic agents were 61.0%, 63.6%, 75.0%, and 63.6% at 3, 6, 12, 24 mo respectively after operation. The outcome parameters of T2DM were significantly improved compaired with that measured before operation (Tables 4 and 5).

| HbA1c level | Preop (n = 77) | 3 mo postop. (n = 77) | 6 mo postop. (n = 77) | 12 mo postop. (n = 56) | 24 mo postop. (n = 33) |

| Without anti-diabetes | 6 (7.8) | 54 (70.1) | 56 (72.7) | 47 (83.9) | 26 (78.8) |

| medications | |||||

| HbA1c < 7.0% | 3 (3.9) | 51 (66.2) | 54 (70.1) | 45 (80.4) | 22 (66.7) |

| HbA1c ≤ 6.5% | 1 (1.3) | 47 (61.0) | 49 (63.6) | 42 (75) | 21 (63.6) |

| HbA1c ≤ 6.0% | 0 (0) | 34 (44.2) | 37 (48.1) | 36 (64.3) | 15 (45.5) |

| With anti-diabetes | 71 (92.2) | 23 (29.9) | 21 (27.3) | 9 (16.1) | 7 (21.2) |

| medications | |||||

| HbA1c < 7.0% | 15 (19.5) | 13 (16.9) | 10 (13.0) | 5 (8.9) | 5 (15.1) |

| HbA1c ≤ 6.5% | 9 (11.7) | 9 (11.7) | 8 (10.4) | 3 (5.4) | 4 (12.1) |

| HbA1c ≤ 6.0% | 4 (5.2) | 3 (3.9) | 3 (3.9) | 3 (5.4) | 1 (3.0) |

| HbA1c level | Preop | 3 mo postop. (n = 77) | 6 mo postop. (n = 77) | 12 mo postop. (n = 56) | 24 mo postop. (n = 33) | P value | |||

| No. of patients | (n = 77) | 3 mo postop vs Preop | 6 mo postop vs Preop | 12 mo postop vs Preop | 24 mo postop vs Preop | ||||

| HbA1c < 7.0% | 18 (23.4) | 64 (83.1) | 64 (83.1) | 50 (89.3) | 27 (81.8) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| HbA1c ≤ 6.5% | 10 (13.0) | 56 (72.7) | 57 (74.0) | 45 (80.4) | 25 (75.8) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| HbA1c ≤ 6.0% | 4 (5.2) | 37 (48.1) | 40 (51.9) | 39 (69.6) | 16 (48.5) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Fifty-six patients (72.7%) were followed up for 12 mo postoperatively. Concomitantdisorders such as hypertension, dyslipidemia and fatty liver were significantly alleviated after surgery than the baselines determined prior to surgery (Table 6).

| Concomitant disorders (n) | Pre-surgery | 12 mo post-surgery | P value |

| Dyslipidemia | 38 | 7 | 0.000 |

| Fatty liver | 31 | 4 | 0.000 |

| Hypertension | 29 | 8 | 0.000 |

The key technology of laparoscopic gastric bypass are gastric pouch formation and gastrojejunostomy, in which the madding of a lesser curvature of independent gastric pouch has reached a consensus[19]. Currently, the surgical techniques applied for anastomosis in LRGB include circular-stapled gastrojejunostomy, linear-stapled gastrojejunostomy, and full hand-sewing gastrojejunostomy. The circular-stapled gastrojejunostomy was first described by Wittgrove in 1994[20], which possesses the characteristic of easily control of anastomosis size. However, this surgical method demands prolonged length of operation time because it is difficult to insert a stapling anvil block inside the gastric pouch and find the active bleeding spot at anastomotic site. Although the technique of full hand-sewing gastrojejunostomy was first reported by Higa et al[4] in 2000, it was not expediently accepted by surgeons due to the requirement of longer learning curve and stronger laparoscopic suture skill. Schauer et al[5] first introduced the linear-stapled gastrojejunostomy in LRYGB, which triumphed over the complexity of stapling anvil block placement in circular-stapled gastrojejunostomy and improved the management of anastomosis bleeding. Several studies show that there was no difference in anastomotic related complication for 25 mm circular-stapled ,full hand-sewing and linear-stapled[6-10]. It is important to control the size of anastomotic for laparoscopic gastric bypass and which in gastrojejunostomy was certainly difficult, but there has no standrad for the methods of gastrojejunostomy nowadays.

The classical linear-stapled gastrojejunostomy anastomoses the posterior of gastric pouch with jejunum and continuous or discontinuous closes the common opening[5]. This method has the advantages of omitting to insert a stapling anvil block inside the gastric pouch as well as easily finding and handling the active bleeding spot at anastomotic site. But it needs a skilled laparoscopic technique to close the common opening, for improper suture may cause the anastomotic stenosis. Considering the shortcomings above, we improve the method of Torres[17] which using circular-stapled gastrojejunostomy in lesser curvature. We take the linear stapler instead of Torres’circular stapler to perform the gastrojejunostomy in lesser curvature of stomach and close the common opening. The width of anastomosis was 2.5 cm (equal to the diameter of 25 mm circular-stapled). It has three advantages, firstly, it not only retaines the linear-stapled advanage, but also easily to standardized, therefore easy to control the anastomosis size, avoiding the laparoscopic suture operation, such shortened the learning curve. Secondly, because we use liner-stapled for side to side anastomosis of the lesser curvature of stomach and jejunum, which insured the width of gastric pouch, so it is easy to formation narrow and long gastric pouch ,and reduces gastric jejunum anastomotic tension. Lastly it can maximize the distance of two closed line, so the anastomosis has better blood supply.

The surgical technique of side-to-side anastomosis of gastric lesser curvature and jejunum in LRYGB was implemented in a total of 77 patients in this study. No patient was switched to laparotomy and no death case was existed. 9 patients received the laparoscopic cholecystectomy at same time during operation. The mean operation time was declined from 2.6 h to 1.5-2.0 h. The mean volume of blood loss during operation was decreased from 58.4 mL to 10-30 mL later stage. The average length of hospital stay was reduced from 5.9 d to 4.0 d at later stage. No gastrointestinal anastomotic bleeding, fistula, stenosis and other complications were observed in whole perioperative duration. All patients did not occur the surgery - related complications during 6-39 mo follow up period except one case (1.3%) showing anastomotic stenosis of gastric jejunum at the sixth week after operation. Compared with the rate of LRYGB gastrointestinal anastomotic complications reported in previous literature[3-16], the surgical technique of linear cutting closer side to side anastomosis of gastric lesser curvature and jejunum adopted in this study is a safe and feasible procedure in clinic. This study also demonstrates that the operation - related complications such as new gallbladder stone, iron deficiency anemia and so on will happen after surgery. The appropriate medical instructions and follow-up guidance to patients after surgery are of great importance.

Previous studies disclosed that bariatric surgery occupied the advantages of long term glycemic remission for obesity patient with type 2 diabetes[21-24]. Schauer et al[21] and Mingrone et al[22] reported the effects of bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for diabetes patients in the prospective, randomized, controlled studies, which indicated that the combination of surgical intervention with conventional medicine would possess the superior therapeutic effectiveness of blood glucose reduction. This result was further confirmed in an additional study of Schauer[25] by 3 years follow-up. In our study, we provide the important evidences of bariatric surgery beneficial to type 2 diabetes management. Gastric bypass surgery is not only able to decline the blood glucose level in type 2 diabetes, but also can improve the management of related complications than any medications alone[25-27]. Furthermore, gastric bypass and other bariatric surgery are capable of alleviating the mortality of diabetes complications[28,29]. This study showed that at the 3, 6, 12, 24 mo postoperative, the BMI (kg/m2) were reduced to 25.8 ± 3.5, 24.3 ± 3.1, 24.0 ± 2.9, and 24.4 ± 2.9 respectively, indicating significant difference compared to the baseline of 31.2 ± 3.5 determined preoperation, The BMI would reach to the minimum level within 1 year after surgery. Similarly, the HbA1c (%) levels at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo after operation were declined to 6.2 ± 0.9, 5.5 ± 0.7, 5.7 ± 0.6, 6.2 ± 1.0 respectively with significant difference in comparison with the baseline of 8.5 ± 1.7 pre-operation. The portions of patients who maintained HbA1c (%) < 6.5% without antidiabetic medicine achieved 61.0%, 63.6%, 75.0%, and 63.6% at 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo respectively. In addition, the improvement of concomitant symptoms, hyperglycemia, lipid metabolism disorder, hypertension and fatty liver were comparable to those in LRYGB patients reported previously.

In conclusion, we have proved in this study that the side-to-side anastomosis of the lesser curvature of stomach and jejunum applied with linear cutting closer in LRYGB is a safe, feasible, and effective therapeutic option in the treatment of obesity patients with type 2 diabetes and complications. But its long-term effect requires more cases and long-term observation. Therefore, the multicenters, larger sample size and longer observation studies are required to further confirm the clinical efficacy of LRYGB to the fat diabetic patients, including the impact on microangiopathy and nephrosis.

The authors would like to thank Gu XZ for biostatistics support and Professor Henry for critically reviewing the manuscript.

With the increasing incidence of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), bariatric surgery has becoming more and more popular as a therapeutic option. At present time, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) is generally applied in the treatment of obesity patient with T2DM. Following 20 years clinical practice, the advantages of this surgery in aspects of curative effectiveness, weight loss, diabetes control and safety are gradually recognized worldwide and has become a gold standard mode for patients indicated.

LRYGB procedure mainly contains 3 processes including gastric pouch formation, gastrojejunostomy and jejunojejunostomy. Wherein, gastrojejunostomy is the most critical step because it needs proficient and skilled surgeon to control the size of anastomosis, which is usually associated with the occurrence of complications. However, the surgical mode has not been standardized. Currently, the diverse surgical techniques applied for anastomosis in LRYGB are circular-stapled gastrojejunostomy (43%), linear-stapled gastrojejunostomy (41%), and full hand-sewn (21%) gastrojejunostomy individually.

In this study, the modified side to side anastomosis of the lesser curvature of stomach and jejunum was applied with linear cutting closer in LRYGB. It has three advantages. Firstly, it not only retaines the linear-stapled advantage, but also easily to standardized, therefore easy to control the anastomosis size, avoiding the laparoscopic suture operation, such shortened the learning curve. Secondly, because we use liner-stapled for side to side anastomosis of the lesser curvature of stomach and jejunum, which insured the width of gastric pouch, so it is easy to formation narrow and long gastric pouch ,and reduces gastric jejunum anastomotic tension. Lastly it can maximize the distance of two closed line, so the anastomosis has better blood supply.

This study suggests that the modified side to side anastomosis of the lesser curvature of stomach and jejunum should been applied with linear cutting closer in LRYGB.

The article is thoughtfully written and has a restricted question it tries to answer. The authors have been careful about not imposing their techniques as the standard.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kassir R, Tarnawski AS S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Littrell MA, Damhorst ML, Littrell JM. Clothing interests, body satisfaction, and eating behavior of adolescent females: related or independent dimensions? Adolescence. 1990;25:77-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1020] [Cited by in RCA: 1004] [Article Influence: 83.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Madan AK, Harper JL, Tichansky DS. Techniques of laparoscopic gastric bypass: on-line survey of American Society for Bariatric Surgery practicing surgeons. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:166-172; discussion 172-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wittgrove AC, Clark GW. Laparoscopic gastric bypass, Roux-en-Y- 500 patients: technique and results, with 3-60 month follow-up. Obes Surg. 2000;10:233-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 554] [Cited by in RCA: 478] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Higa KD, Boone KB, Ho T. Complications of the laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 1,040 patients--what have we learned? Obes Surg. 2000;10:509-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schauer PR, Ikramuddin S, Gourash W, Ramanathan R, Luketich J. Outcomes after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2000;232:515-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 940] [Cited by in RCA: 825] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gonzalez R, Lin E, Venkatesh KR, Bowers SP, Smith CD. Gastrojejunostomy during laparoscopic gastric bypass: analysis of 3 techniques. Arch Surg. 2003;138:181-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bendewald FP, Choi JN, Blythe LS, Selzer DJ, Ditslear JH, Mattar SG. Comparison of hand-sewn, linear-stapled, and circular-stapled gastrojejunostomy in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1671-1675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee S, Davies AR, Bahal S, Cocker DM, Bonanomi G, Thompson J, Efthimiou E. Comparison of gastrojejunal anastomosis techniques in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: gastrojejunal stricture rate and effect on subsequent weight loss. Obes Surg. 2014;24:1425-1429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shope TR, Cooney RN, McLeod J, Miller CA, Haluck RS. Early results after laparoscopic gastric bypass: EEA vs GIA stapled gastrojejunal anastomosis. Obes Surg. 2003;13:355-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Giordano S, Salminen P, Biancari F, Victorzon M. Linear stapler technique may be safer than circular in gastrojejunal anastomosis for laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a meta-analysis of comparative studies. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1958-1964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Qureshi A, Podolsky D, Cumella L, Abbas M, Choi J, Vemulapalli P, Camacho D. Comparison of stricture rates using three different gastrojejunostomy anastomotic techniques in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:1737-1740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bohdjalian A, Langer FB, Kranner A, Shakeri-Leidenmühler S, Zacherl J, Prager G. Circular- vs. linear-stapled gastrojejunostomy in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2010;20:440-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Penna M, Markar SR, Venkat-Raman V, Karthikesalingam A, Hashemi M. Linear-stapled versus circular-stapled laparoscopic gastrojejunal anastomosis in morbid obesity: meta-analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:95-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bakhos C, Alkhoury F, Kyriakides T, Reinhold R, Nadzam G. Early postoperative hemorrhage after open and laparoscopic roux-en-y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2009;19:153-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Podnos YD, Jimenez JC, Wilson SE, Stevens CM, Nguyen NT. Complications after laparoscopic gastric bypass: a review of 3464 cases. Arch Surg. 2003;138:957-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 541] [Cited by in RCA: 447] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Finks JF, Carlin A, Share D, O’Reilly A, Fan Z, Birkmeyer J, Birkmeyer N. Effect of surgical techniques on clinical outcomes after laparoscopic gastric bypass--results from the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7:284-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Torres JC, Oca CF, Garrison RN. Gastric bypass: Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy from the lesser curvature. South Med J. 1983;76:1217-1221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chinese Diabetes Society. Chinese Diabetes Society. China guideline for type 2 diabetes (2013). Zhongguo Tangniaobing Zazhi. 2014;6:447-498. |

| 19. | Capella RF, Iannace VA, Capella JF. An analysis of gastric pouch anatomy in bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2008;18:782-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wittgrove AC, Clark GW, Tremblay LJ. Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass, Roux-en-Y: Preliminary Report of Five Cases. Obes Surg. 1994;4:353-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 568] [Cited by in RCA: 458] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, Brethauer SA, Kirwan JP, Pothier CE, Thomas S, Abood B, Nissen SE, Bhatt DL. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1567-1576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1639] [Cited by in RCA: 1588] [Article Influence: 122.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, Guidone C, Iaconelli A, Leccesi L, Nanni G, Pomp A, Castagneto M, Ghirlanda G. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-1585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1340] [Cited by in RCA: 1273] [Article Influence: 97.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pories WJ, Swanson MS, MacDonald KG, Long SB, Morris PG, Brown BM, Barakat HA, deRamon RA, Israel G, Dolezal JM. Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 1995;222:339-350; discussion 350-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1610] [Cited by in RCA: 1455] [Article Influence: 48.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Adams TD, Davidson LE, Litwin SE, Kolotkin RL, LaMonte MJ, Pendleton RC, Strong MB, Vinik R, Wanner NA, Hopkins PN. Health benefits of gastric bypass surgery after 6 years. JAMA. 2012;308:1122-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 489] [Cited by in RCA: 473] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, Wolski K, Brethauer SA, Navaneethan SD, Aminian A, Pothier CE, Kim ES, Nissen SE. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes--3-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2002-2013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1202] [Cited by in RCA: 1177] [Article Influence: 107.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pérez G, Devaud N, Escalona A, Downey P. Resolution of early stage diabetic nephropathy in an obese diabetic patient after gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1388-1391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Müller-Stich BP, Fischer L, Kenngott HG, Gondan M, Senft J, Clemens G, Nickel F, Fleming T, Nawroth PP, Büchler MW. Gastric bypass leads to improvement of diabetic neuropathy independent of glucose normalization--results of a prospective cohort study (DiaSurg 1 study). Ann Surg. 2013;258:760-765; discussion 765-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Banks J, Adams ST, Laughlan K, Allgar V, Miller GV, Jayagopal V, Gale R, Sedman P, Leveson SH. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass could slow progression of retinopathy in type 2 diabetes: a pilot study. Obes Surg. 2015;25:777-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, Ahlin S, Andersson-Assarsson J, Anveden Å, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, Karason K, Lönroth H, Näslund I, Sjöström E, Taube M, Wedel H, Svensson PA, Sjöholm K, Carlsson LM. Association of bariatric surgery with long-term remission of type 2 diabetes and with microvascular and macrovascular complications. JAMA. 2014;311:2297-2304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in RCA: 739] [Article Influence: 67.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |