Published online Sep 7, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i33.7579

Peer-review started: April 6, 2016

First decision: May 12, 2016

Revised: June 20, 2016

Accepted: July 6, 2016

Article in press: July 6, 2016

Published online: September 7, 2016

Processing time: 152 Days and 3.1 Hours

To summarize and compare the clinical characteristics of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) and primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC).

A total of 124 patients with DILI and 116 patients with PBC treated at Shengjing Hospital Affiliated to China Medical University from 2005 to 2013 were included. Demographic data (sex and age), biochemical indexes (total protein, albumin, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, indirect bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and gamma glutamyltransferase), immunological indexes [immunoglobulin (Ig) A, IgG, IgM, antinuclear antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, anti-mitochondrial antibody, and anti-mitochondrial antibodies] and pathological findings were compared in PBC patients, untyped DILI patients and patients with different types of DILI (hepatocellular type, cholestatic type and mixed type).

There were significant differences in age and gender distribution between DILI patients and PBC patients. Biochemical indexes (except ALB), immunological indexes, positive rates of autoantibodies (except SMA), and number of cases of patients with different ANA titers (except the group at a titer of 1:10000) significantly differed between DILI patients and PBC patients. Biochemical indexes, immunological indexes, and positive rate of autoantibodies were not quite similar in different types of DILI. PBC was histologically characterized mainly by edematous degeneration of hepatocytes (n = 30), inflammatory cell infiltration around bile ducts (n = 29), and atypical hyperplasia of small bile ducts (n = 28). DILI manifested mainly as fatty degeneration of hepatocytes (n = 15) and spotty necrosis or loss of hepatocytes (n = 14).

Although DILI and PBC share some similar laboratory tests (biochemical and immunological indexes) and pathological findings, they also show some distinct characteristics, which are helpful to the differential diagnosis of the two diseases.

Core tip: This is a retrospective study to distinguish differential diagnosis of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) and primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC). There are many similarities between the clinical manifestations and biochemical tests of the two diseases. DILI and PBC also show some distinct characteristics, which are helpful to the differential diagnosis of the two diseases.

- Citation: Yang J, Yu YL, Jin Y, Zhang Y, Zheng CQ. Clinical characteristics of drug-induced liver injury and primary biliary cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(33): 7579-7586

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i33/7579.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i33.7579

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) as an important cause of acute liver failure and chronic liver injury has increasingly been recognized. With the continuous development of new drugs and the increase in the type of drugs, there have been more and more clinical reports on DILI. However, since DILI has diverse clinical manifestations and lack a diagnostic gold standard, misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis often occur. Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is an autoimmune liver disease. The constant improvement of diagnostic techniques has led to an increasing number of detected PBC cases. Both DILI and PBC may develop symptoms such as jaundice, fatigue, anorexia, and upper abdominal discomfort. PBC often has a chronic course, and it is diagnosed based mainly on the presence of liver function abnormalities and a variety of autoantibodies; however, a small portion of PBC patients may have an acute onset and show negative autoantibodies. In addition, DILI patients may be seropositive for some autoantibodies, and 20%-25% of DILI cases belong to the cholestatic type. Therefore, it is somewhat difficult to distinguish between DILI and PBC in some cases. In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the clinical data for 124 patients with DILI and 116 patients with PBC treated at Shengjing Hospital Affiliated to China Medical University from 2005 to 2013, with an aim to provide some meaningful evidence for improving the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of the two diseases.

A total of 124 patients with DILI and 116 patients with PBC treated at Shengjing Hospital Affiliated to China Medical University from 2005 to 2013 were included. PBC was diagnosed according to the diagnostic criteria recommended by the 2009 European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) Clinical Practice Guidelines for management of cholestatic liver diseases[1]: (1) alkaline phosphatase (ALP) > 2 times the upper limit of normal (ULN) or gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) > 5 times the ULN; (2) positivity for serum antimitochondrial antibody (AMA) or AMA-M2; and (3) liver biopsy showing characteristic small bile duct injury (non-suppurative cholangitis and intrahepatic small bile duct damage). When two of the above three items were met, PBC was diagnosed. Patients with viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, drug-induced hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease and other diseases that can cause liver damage as well as patients with incomplete clinical information were excluded. DILI was diagnosed according to the RUCAM consensus developed in 1993[2,3], and patients with an RUCAM score ≥ 6 were included in this study. According to the criteria developed by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences in 1989[4] and the criteria revised in 2005 by the United States Food and Drug Administration drug hepatotoxicity steering committee[5], DILI was clinically divided into (1) hepatocellular type: alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ≥ 3 × ULN and ALT/ALP ≥ 5; (2) cholestatic type: ALP ≥ 2 × ULN and ALT/ALP ≤ 2; (3) mixed type: ALT ≥ 3 × ULN, ALP ≥ 2 × ULN, and ALT/ALP > 2 but < 5.

The following clinical data were collected: (1) demographic data including gender and age; (2) biochemical indexes including total protein (TP), albumin (ALB), ALT, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin (TBIL), direct bilirubin (DBIL), indirect bilirubin (IBIL), ALP and GGT; (3) immunological indexes including immunoglobulin (Ig) A, IgG, IgM, antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-smooth muscle antibody (SMA), AMA, and AMA subtypes M2, M4 and M9; and (4) liver biopsy (48 PBC patients and 19 DILI patients underwent B-mode ultrasound guided liver biopsy to analyze the pathological features).

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS19.0 software. Continuous data are expressed the mean ± SD. Data following a normal distribution were compared using the t-test, while those not following a normal distribution are described as medians. Categorical data are expressed as percentages and compared using the χ2 test. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

In both the DILI and PBC groups, the percentage of females was higher than that of males (72.6% vs 27.4% and 91.4% vs 8.6%, respectively). The mean age of onset was 48.43 ± 14.3 years for DILI patients, and 56.89 ± 9.87 years for PBC patients. There were significant differences in gender distribution and mean age between the two groups (P < 0.05).

Both DILI and PBC patients showed varying degrees of elevations of ALT, AST, GGT, ALP, TBIL, DBIL and IBIL. AST and ALT were significantly higher in the DILI group than in the PBC group (P < 0.05), while ALP and GGT were significantly higher in the PBC group (P < 0.05). ALB showed no significant difference between the two groups (Table 1).

| TP (g/L) | ALB (g/L) | AST (U/L) | ALT (U/L) | ALP (U/L) | GGT (U/L) | TBIL (μmol/L) | DBIL (μmol/L) | IBIL (μmol/L) | |

| DILI (n = 124) | 66.2 ± 7.2 | 38.8 ± 5.6 | 391.0 (148.0-731.0) | 503.0 (263-904) | 179.0 (121.0-294.0) | 200 (108.0-373.0) | 31.5 (14.88-109.2) | 49.3 (15.9-139.6) | 16.0 (10.6-37.2) |

| PBC (n = 116) | 74.9 ± 9.4 | 37.6 ± 5.9 | 113.5 (74.8-190.5) | 113.0 (69.0-193.3) | 264.0 (166.3-443.3) | 311.5 (148.0-660.3) | 78.6 (25.2-189.0) | 16.3 (5.78-60.6) | 10.9 (7.38-21.6) |

PBC patients showed elevations of IgG, IgM and IgA, with IgM having the most remarkable elevation. In contrast, DILI patients showed no elevation of IgG, IgM or IgA. There were significant differences in IgG, IgM and IgA levels between the two groups (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

| IgG (g/L) | IgM (g/L) | IgA (g/L) | |

| DILI (n = 124) | 13.1 ± 3.7 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 1.2 |

| PBC (n = 116) | 18.8 ± 7.7 | 4.4 ± 2.9 | 3.4 ± 1.5 |

Of all the DILI patients (n = 124), 59 (47.5%) were positive for autoantibodies, most of which had a low titer. There were 55 (44.3%) patients positive for ANA, including 12 (9.67%) having a titer > 1:100, 43 (34.6%) having a titer of 1:100, 9 (7.25%) having a titer of l:320, 2 (1.61%) having a titer of l:1000 and 1 (0.80%) having a titer of 1:3200; 4 (3.22%) positive for SMA; 4 (3.22%) positive for AMA; 3 (2.42%) positive for AMA-M2; 1 (0.80%) positive for AMA-M4; and 3 (2.42%) positive for AMA-M9. Except that one patient was moderately positive for SMA, the other patients only showed weak positivity for SMA, AMA-M2, AMA-M4 or AMA-M9. Of all the PBC patients (n = 116), 106 (91.3%) were positive for autoantibodies, most of which had a high titer. There were 98 (84.4%) patients positive for ANA, including 78 (67.2%) having a titer > 1:100, 20 (17.2%) having a titer of 1:100, 27 (23.2%) having a titer of 1:320, 30 (25.8%) having a titer of 1:1000, 19 (16.3%) having a titer of 1:3200, and 2 (1.72%) having a titer of 1:10000; 2 (3.45%) positive for SMA; 98 (84.4%) positive for AMA; 98 (84.4%) positive for AMA-M2; 34 (29.3%) positive for AMA-M4; and 19 (16.3%) positive for AMA-M9. With regards to the degree of positivity, there were 80 cases of moderate positivity and 18 cases of weak positivity for AMA; 19 cases of strong positivity, 69 cases of moderate positivity and 10 cases of weak positivity for AMA-M2; 12 cases of moderate positivity and 22 cases of weak positivity for AMA-M4; 5 cases of moderate positivity and 14 cases of weak positivity for AMA-M9; and all cases of weak positivity for SMA2. Except for SMA, the percentage of cases positive for other autoantibodies differed significantly between DILI and PBC patients (P < 0.05). The number of cases positive for ANA at all titers were significantly different between DILI and PBC patients (P < 0.05) except ANA at a titer of 1:10000 (Tables 3 and 4).

| ANA | AMA | SMA | AMA-M2 | AMA-M4 | AMA-M9 | |

| DILI (n = 124) | 55 (44.3) | 4 (3.22) | 4 (3.22) | 3 (2.42) | 1 (0.80) | 3 (2.42) |

| PBC (n = 116) | 98 (84.4) | 98 (84.4) | 2 (3.45) | 98 (84.4) | 34 (29.3) | 19 (16.3) |

| χ2 | 41.761 | 161.932 | 0.554 | 165.598 | 39.091 | 14.027 |

| P value | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.685 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| 1:100 | 1:320 | 1:1000 | 1:3200 | 1:10000 | |

| DILI (n = 124) | 43 (34.6) | 9 (7.25) | 2 (1.61) | 1 (0.80) | 0 |

| PBC (n = 116) | 20 (17.2) | 27 (23.2) | 30 (25.8) | 19 (16.3) | 2 (1.72) |

| χ2 | 9.412 | 12.060 | 30.498 | 19.027 | 2.156 |

| P value | 0.0002 | 0.001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.233 |

Of all the 124 cases of DILI, 90 belonged to the hepatocellular type, 20 belonged to the cholestatic type, and 14 to the mixed type. AST, ALT, GGT, TBIL, DBIL, IBIL, IgM, IgA and IgG differed significantly between the hepatocellular type DILI, cholestatic type DILI, mixed type DILI, and PBC groups, although ALB showed no significant difference. AST, ALT, GGT, TBIL, DBIL, and IBIL were elevated in all types of DILI and PBC. AST and ALT were elevated more significantly in mixed type DILI than in cholestatic type DILI and PBC (P < 0.05). AST was elevated more significantly in hepatocellular type DILI than in mixed type DILI, cholestatic type DILI and PBC (P < 0.05). GGT rose remarkably in the PBC group, which was significantly higher than that in the hepatocellular type DILI group (P < 0.05). TBIL, DBIL and IBIL significantly rose in the cholestatic type group. Although ALP showed no remarkable elevation in the hepatocellular type group, it was elevated in the other three groups and showed no significant difference among the three groups. IgM, IgA and IgG were elevated in the PBC group, with IgM having the most prominent rise. IgM, IgA and IgG in the PBC group were significantly different from those in the other three groups (P < 0.05) (Tables 5 and 6). The positive rates of the majorities of autoantibodies differed significantly between the hepatocellular type DILI, cholestatic type DILI, mixed type DILI, and PBC groups. Except for SMA and ANA at a titer of 1:10000 (P = 0.797, 0.506), the positive rates of other autoantibodies differed significantly between the hepatocellular type DILI and PBC groups. Except for AMA-M9, SMA and ANA at a titer of 1:100 (P = 0.306, 0.382, 0.531, 0.306), the positive rates of other autoantibodies differed significantly between the cholestatic type DILI and PBC groups. When comparing the mixed type DILI and PBC groups, AMA-M4, AMA-M9 and SMA (P = 0.111, 0.694, 0.292) as well as ANA at different titers showed no significant differences. The positive rates of autoantibodies did not differ significantly between various types of DILI (Tables 7 and 8).

| TP (g/L) | ALB (g/L) | AST (U/L) | ALT (U/L) | ALP (U/L) | GGT (U/L) | TBIL (μmol/L) | DBIL (μmol/L) | IBIL (μmol/L) | |

| Hepatocellular type DILI (n = 90) | 66.8 ± 8.0a | 39.2 ± 6.2 | 442.5 (174.3-941.5)a | 574.0 (205.6-1263.3)ace | 145.5 (86.3-217.5)ace | 179.0 (87.0-366.1)a | 74.30 (32.4-160.7) | 46.2 (17.8-96.6) | 16.2 (11.4-19.5) |

| Cholestatic type DILI (n = 20) | 63.7 ± 7.2a | 39.1 ± 5.8 | 135.0 (82.6-185.8) | 154.0 (49.2-253.8) | 320.6 (196.6-454.2) | 208.50 (110.5-426.8) | 126.90 (55.3-266.7) | 99.0 (38.8-214.3) | 26.2 (13.3-35.2) |

| Mixed type DILI (n = 14) | 70.8 ± 8.6 | 37.6 ± 4.4 | 654.1 (317.2-1389.1)ac | 844.0 (551.8-1945.8)ac | 328.75 (258.4-477.2) | 260.50 (142.8-418.5) | 111.10 (41.3-234.9)a | 95.2 (56.7-266.8)a | 21.9 (14.6-33.2)a |

| PBC (n = 116) | 74.9 ± 9.4 | 37.6 ± 6.0 | 113.5 (74.8-190.5) | 113.0(69.0-193.3) | 264.0 (166.3-443.3) | 311.5 (148.0-660.3) | 78.6 (25.2-189.0) | 16.3 (5.8-60.6) | 10.9 (7.4-21.6) |

| Autoantibodies | ANA | AMA | SMA | AMA-M2 | AMA-M4 | AMA-M9 | |

| Hepatocellular type DILI (n = 90) | 43 (47.7)a | 41 (45.5)a | 2 (2.22)a | 2 (2.22) | 2 (2.22)a | 0a | 1 (1.11)a |

| Cholestatic type DILI (n = 20) | 10 (50.0)a | 8 (40.0)a | 2 (10.0)a | 1 (5.00) | 1 (5.00)a | 0a | 1 (5.00) |

| Mixed type DILI (n = 14) | 6 (42.8)a | 6 (42.8)a | 0a | 1 (7.14) | 0a | 1 (7.14) | 1 (7.14) |

| PBC (n = 116) | 106 (91.3) | 98 (84.4) | 98 (84.4) | 2 (1.72) | 98 (84.4) | 34 (29.3) | 19 (16.3) |

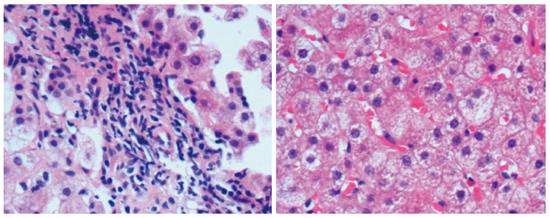

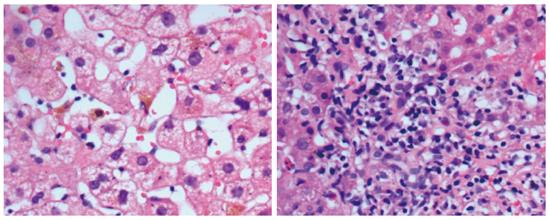

Forty-eight PBC patients and 19 DILI patients underwent liver biopsy. Histologically, PBC manifested mainly as edematous degeneration of hepatocytes (n = 30) with cell necrosis (mainly spotty and patchy necrosis), inflammatory cell infiltration around the bile ducts (n = 29; the main infiltrating cell type was lymphocytes, with plasma cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils visible), atypical hyperplasia of small bile ducts (n = 28), decreased number or disappearance of interlobular bile ducts (n = 16), granulomatous changes (n = 11), cholestasis (n = 8), and fibrous hyperplasia and expansion around bile ducts (n = 14). DILI manifested mainly as fatty degeneration of hepatocytes (n = 15), spotty necrosis or loss of hepatocytes (n = 14), infiltration of mixed types of inflammatory cells (mainly eosinophils and neutrophils) around hepatocytes (n = 16), epithelioid granuloma (n = 1), hepatocellular cholestasis (n = 9), and cholangiolitic cholestasis (n = 3) (Figures 1 and 2).

DILI is an iatrogenic form of liver injury caused directly by drugs or their metabolites or hypersensitivity to them in the process of drug therapy, frequently occurring about 5-90 d after medication. In some Western countries, DILI is an important cause of acute liver failure[6,7]. The diagnosis of DILI is a process of exclusion, in which medication history, onset time after medication, duration, risk factors for adverse drug reactions, drugs used, factors that can result in exclusions, laboratory findings, previously reported liver damage associated with the drug use, and response to re-medication should be assessed to identify the possible causality[2]. PBC is a chronic, progressive, immune-mediated cholestatic disease that occurs mainly in middle-aged women. Characterized by AMA and (or) AMA-M2 positivity, PBC manifests mainly as non-suppurative damage to small intrahepatic bile ducts, portal area expansion, inflammatory responses, and serious intrahepatic cholestasis. Although the course of PBC is chronic, it can eventually lead to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis[8]. Risk factors for DILI include gender, age, race, underlying liver disease, alcohol consumption, combined drug use, and genetic susceptibility. Women are susceptible to DILI[9,10]. In the present study, it was found that the proportion of women was 72.6% in DILI patients, and 91.4% in PBC patients. The onset age was 48.43 ± 14.3 years for DILI patients, and 56.89 ± 9.87 years for PBC patients. These findings are similar to the mean onset age of DILI (approximately 45 years) and PBC (approximately 50 years) reported in the literature, and in line with the characteristic of woman susceptibility to DILI and PBC (approximately 90%)[11,12]. Our results showed that PBC had a more significant preponderance of females, and most patients had an onset age of 40 years or older and younger patients were rare. In contrast, the onset age of DILI had a large span: the youngest patient was 18 years old and the oldest was 81 years old. Young DILI patients were not rare.

Biochemical tests showed that AST and ALT levels were significantly higher in untyped DILI patients than in patients with PBC, while ALP and GGT levels were significantly higher in PBC patients than in patients with DILI. This is because DILI is often the hepatocellular type, which is characterized by significantly increased aminotransferase levels and hepatocyte necrosis, while PBC is characterized by severe cholestasis and bile duct damage. Based on AST and ALP levels, DILI is divided into the hepatocellular type, cholestatic type and mixed type. Our results showed that the proportion of the hepatocellular type was the highest (72.5%), followed by the cholestatic type (16.1%) and the mixed type (11.2%). This finding is consistent with the DILI typing results of some studies, which also showed that hepatocellular type is the most common type of DILI. In the present study, the mixed type had more severe liver injury than the other types, the hepatocellular type and mixed group had more significant AST and ALT elevations than cholestatic type DILI and PBC, bilirubin was significantly higher in the mixed group than in the other three groups, and GGT and ALP in the mixed type and cholestatic type DILI groups were not significantly different from those in the PBC group, but significantly differed from those in the hepatocellular type group. Some studies reported that mixed type DILI is in essence within the category of cholestatic type DILI, because they can change into each other in the course of the disease, and have a greater chance of chronicity than the hepatocellular type[13]. Some drugs (amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, erythromycin estolate, chlorpromazine, carbamazepine, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, oral contraceptives, etc.) can activate the immune mechanism of the liver, and if not promptly withdrawn, they can lead to chronic liver injury, such as non-suppurative cholangitis, which is similar to PBC[6]. This study found that mixed type DILI and PBC had significant differences in elevated transaminases and bilirubin, while cholestatic type DILI and PBC had no significant differences in all biochemical indexes except total protein. Given that DILI patients may also test positive for autoantibodies and there have been reports that DILI can progress into PBC and AIH (autoimmune hepatitis)-PBC overlap syndrome[14] or PBC was misdiagnosed as DILI[15], clinicians should pay more attention to the differential diagnosis of DILI from PBC in clinical practice.

With regards to immunological indexes, IgG, IgM and IgA showed no significant elevations in untyped DILI and all three types of DILI, while these immunoglobulins were significantly elevated in the PBC group, with IgM having the most prominent elevation. This conforms to the characteristic of PBC that IgM has an obvious rise, which is helpful in differentiating PBC and DILI. Drug induced hepatotoxicity is generally divided into two categories: predictable and non-predictable. Predictable DILI is often due to direct toxic effects of drug themselves or their metabolites on liver cells. Non-predictable DILI is caused by specific or non-specific immune responses induced by drugs[16,17], which result in the recognition of specific drug related antigens and make certain autoantibodies such as anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody, anti-parietal cell antibody, anti-liver cytosol antibody type 1, SMA and ANA become positive[18]. Most scholars believe that the immune mechanism of pathogenesis of PBC involves the breakdown of the body’s immune tolerance and the loss of ability to tolerate auto-antigens. As a result, the immune system continuously attacks intrahepatic bile ducts, thereby resulting in cholangitis and cholestasis. AMA and (or) AMA-M2 antibodies are the most typical examples[19]. In contrast, autoantibodies in DILI may not be a cause of liver damage, but may be the result of liver damage[18]. In most cases of DILI, autoantibodies disappeared or showed a reduction in titer in the process of liver repair, which is a different feature from autoantibodies in PBC. The present study showed that ANA positivity was most common in DILI patients, and a few cases tested positive for AMA, SMA, AMA-M2, AMA-M4, AMA-M9, although most of the cases were weakly positive. In contrast, PBC patients were positive mainly for ANA, AMA, and AMA-M2, and the majority of cases showed strong positivity and had high titer antibodies. The positive rates of all autoantibodies except ANA at a titer of 1:10000 exhibited significant differences between uptyped DILI and PBC. There were no significant differences in all autoantibodies between different types of DILI, and DILI of various types showed no significant differences from PBC in the positive rates of SMA and ANA at a titer of 1:10000. Mixed type and cholestatic type DILI were more similar to PBC in the positive rates of autoantibodies, and this may be because there were fewer cases of mixed type and cholestatic type DILI. In this study, the majority of DILI patients who tested positive for some autoantibodies underwent liver biopsy to achieve a clear diagnosis on the basis of medication history. For patients who were negative for PBC specific autoantibodies, liver biopsy was required to obtain a definite diagnosis. This suggests that liver biopsy is helpful to differentiate between DILI and PBC. For DILI patients who are positive for autoantibodies, regular monitoring of autoantibodies and biochemical indexes is necessary to detect the possibility of progressing to autoimmune liver disease.

Pathological analysis showed that both DILI and PBC had varying degrees of hepatocyte necrosis, edema, inflammatory cell infiltration and cholestasis, but DILI mainly manifested as eosinophil and neutrophil infiltration, cholangiolitic and hepatocellular cholestasis, while PBC was characterized by lymphocyte infiltration around bile ducts and cholestasis, destruction, progressive reduction and disappearance, and fibrosis of small bile ducts. Pathologically, DILI was characterized mainly by epithelioid granuloma, eosinophil infiltration around hepatocytes, and hepatocyte necrosis or loss. DILI with cholangiolitic cholestasis rarely progressed to vanishing bile duct syndrome. The features that PBC patients often test positive for specific autoantibodies, the liver function of DILI patients frequently recovers after the cessation of drugs, and very few DILI cases are complicated with other autoimmune diseases such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Sjogren’s syndrome[20] provide powerful evidence for differentiating DILI and PBC.

With the increase in the type of drugs, more and more DILI cases have increasingly been caused. The improvement in PBC diagnostic standards, advances in diagnostic technology and wide use of liver biochemistry tests in China have resulted in increasing annual detection rates of DILI. However, there have been no diagnostic gold standards for DILI so far. Since DILI often exhibits similar clinical manifestations and biochemical findings to PBC, and both DILI and PBC patients may be positive for some autoantibodies and only show mild early symptoms or biochemical abnormalities in physical examination, the differential diagnosis of PBC and DILI is difficult in some cases. Given that there have currently been few studies on the differential diagnosis of PBC and DILI, this study analyzed the clinical data for PBC patients and typed and untyped DILI patients to summarize and compare their clinical characteristics, with an aim to provides useful information for the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of the two diseases. However, the total number of DILI patients and the number of pathological samples were not large enough, and the sample size for different types of DILI was small. Future larger-sample studies will be required to address this issue.

With the continuous improvement of diagnostic techniques, the incidence of primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) as a kind of autoimmune liver disease, is also increasing. PBC and drug-induced liver injury (DILI) may appear similar clinical manifestations, yellow dye, fatigue, anorexia, abdominal discomfort, etc. PBC mostly shows a chronic course of disease. In diagnosis, PBC is mainly based on the abnormal liver function and many kinds of autoantibodies, but few patient may have negative autoantibodies. Some DILI patients may be antibody positive, and about 20%-25% of DILI cases belong to cholestatic liver disease. So it is difficult to distinguish between PBC and DILI.

There have been few reports on the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of PBC and DILI. From the current report, DILI and PBC share some similar laboratory tests (biochemical and immunological indexes) and pathological findings. The result of this study contribute to the differential diagnosis of the two diseases.

Detection of biochemical indexes and immunology indexes in DILI (before and after typing) and PBC was very useful. By comparison, differences in both biochemical indexes (TP, AST, ALT, ALP, TBIL, DBIL, GGT, and IBIL) and immunological indexes (IgA, IgG, IgM, ANA, and AMA) were statistically significant.

This study suggests that detection of biochemical indexes (TP, AST, ALT, ALP, TBIL, DBIL, GGT, and IBIL) and immunological indexes is useful for diagnosing DILI and PBC.

DILI is an iatrogenic form of liver injury caused directly by drugs or their metabolites or hypersensitivity to them in the process of drug therapy, frequently occurring about 5-90 d after medication. PBC is a chronic, progressive, immune-mediated cholestatic disease that occurs mainly in middle-aged women. Characterized by AMA and (or) AMA-M2 positivity, PBC manifests mainly as non-suppurative damage to small intrahepatic bile ducts, portal area expansion, inflammatory responses, and serious intrahepatic cholestasis.

In this manuscript, the authors analyzed the clinical characteristics of DILI and PBC. Although DILI and PBC share some similar laboratory tests (biochemical and immunological indexes) and pathological findings, they also show some distinct characteristics, which are helpful to the differential diagnosis of the two diseases. Over all, this study is well designed and the manuscript is well written.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Burgoyne G, Kim KC, Mullan MJ S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of cholestatic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2009;51:237-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1382] [Cited by in RCA: 1199] [Article Influence: 74.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Danan G, Benichou C. Causality assessment of adverse reactions to drugs--I. A novel method based on the conclusions of international consensus meetings: application to drug-induced liver injuries. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1323-1330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1015] [Cited by in RCA: 1068] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zeng LL, Zhou GQ. Drug-induced liver injury: diagnostic criteria and clinical application. Yaowu Buliang Fanying Zazhi. 2011;13:17-20. |

| 4. | Bénichou C. Criteria of drug-induced liver disorders. Report of an international consensus meeting. J Hepatol. 1990;11:272-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 780] [Cited by in RCA: 772] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Navarro V. Hepatic adverse event nomenclature document [EB/OL]. (20061117). Available from: http://www.fda.gov/cder/livertox/presentaions 2005/vic_Navarro.ppt. |

| 6. | Watkins PB, Seeff LB. Drug-induced liver injury: summary of a single topic clinical research conference. Hepatology. 2006;43:618-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shakil AO, Kramer D, Mazariegos GV, Fung JJ, Rakela J. Acute liver failure: clinical features, outcome analysis, and applicability of prognostic criteria. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:163-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lindor KD, Gershwin ME, Poupon R, Kaplan M, Bergasa NV, Heathcote EJ; American Association for Study of Liver Diseases. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;50:291-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 933] [Cited by in RCA: 896] [Article Influence: 56.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fontana RJ, Seeff LB, Andrade RJ, Björnsson E, Day CP, Serrano J, Hoofnagle JH. Standardization of nomenclature and causality assessment in drug-induced liver injury: summary of a clinical research workshop. Hepatology. 2010;52:730-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, Watkins PB, Davern T, Serrano J, Yang H, Rochon J; Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN). Causes, clinical features, and outcomes from a prospective study of drug-induced liver injury in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1924-134, 1924-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 624] [Cited by in RCA: 610] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang J, Liu DW, Zhan YS. Advances in epidemiological research of drug-induced liver diseases. Modern Preventive Medicine. 2010;37:1393-1395. |

| 12. | Hirschfield GM. Diagnosis of primary biliary cirrhosis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:701-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Andrade RJ, Lucena MI, Kaplowitz N, García-Muņoz B, Borraz Y, Pachkoria K, García-Cortés M, Fernández MC, Pelaez G, Rodrigo L. Outcome of acute idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury: Long-term follow-up in a hepatotoxicity registry. Hepatology. 2006;44:1581-1588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Teng GJ, Zhang W, Sun Y, Zhao J, Zou ZS. Drug-induced hepatitis progresses to autoimmune liver disease: a report of three cases and literature review. Ganzang. 2010;15:397-399. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Sohda T, Shiga H, Nakane H, Nishizawa S, Yoshikane M, Anan A, Suzuki N, Irie M, Iwata K, Watanabe H. Rapid-onset primary biliary cirrhosis resembling drug-induced liver injury. Intern Med. 2005;44:1051-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang XX, Liu YM, Liu H, Sun L, Liao HJ, Lv FD. Clinical pathology features analysis of drug-induced liver injury in patients with autoantibodies. Zhongguo Yiyao Daobao. 2013;10:85-87. |

| 17. | Rao YF, Zheng FY, Zhang XG. Immune mechanism of drug-induced liver injury. Zhongguo Yaoxue Zazhi. 2008;43:1207-1210. |

| 18. | Liu YM. The clinical feature and prognosis in patients with drug induced liver injury complicated with positive autoantibodies detection. Linchuang Gandanbing Zazhi. 2012;28:335-338. |

| 19. | Fan L, Zhong R. Studies on pathogenesis of primary biliary cirrhosis. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2002;10:392-394. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Degott C, Feldmann G, Larrey D, Durand-Schneider AM, Grange D, Machayekhi JP, Moreau A, Potet F, Benhamou JP. Drug-induced prolonged cholestasis in adults: a histological semiquantitative study demonstrating progressive ductopenia. Hepatology. 1992;15:244-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |