Published online Aug 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i30.6936

Peer-review started: April 5, 2016

First decision: May 12, 2016

Revised: June 11, 2016

Accepted: July 6, 2016

Article in press: July 6, 2016

Published online: August 14, 2016

Processing time: 128 Days and 1 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the safety of the implantation of a new device for the treatment of anal fistulas. The short-term clinical efficacy was also assessed.

METHODS: This study took place at a tertiary care university hospital. Patients with a complex anal fistula of cryptoglandular origin were enrolled in the study and were treated with insertion of the new device. All patients were evaluated by clinical and physical examination, including an endoanal ultrasound at the baseline, and then at the 2 wk and 1, 2, 3 and 6-mo follow-up visits.

RESULTS: Morbidity, continence status, and success rate were the main outcome measures. Ten patients underwent the placement of the new device. The fistulas were transphincteric in eight patients and extrasphincteric in the remaining two. The median duration of the surgical procedure was 34.5 (range, 27-42) min. Neither intra- nor postoperative complications occurred, and all patients were discharged the day after the procedure. At the 6-mo follow-up evaluation, the final success rate was 70%. Three failures were registered: a device expulsion (on the 10th postoperative day), the persistence of inflammatory tissue around the fistula tract (at the 2-mo follow up), and the persistence of serum discharge (at the 6-mo follow up). No patient experienced any change incontinence, as assessed by the Cleveland Clinic Fecal Incontinence score.

CONCLUSION: The technical procedure is simple and has low risk of perioperative morbidity. The pre- and post-operative continence status did not change in any of the patients. The initial results at the 6-mo follow up seem to be promising. However, a longer follow-up period and a larger sample size are needed to confirm these preliminary results.

Core tip: Surgical treatment of anal fistulas is still controversial. This prospective study is the first to reporton the implantation of a new device, the Curaseal AF™ device. Several interesting results emerged concerning the safety of the procedure and its effectiveness in the short-term follow-up.

- Citation: Ratto C, Litta F, Donisi L, Parello A. Prospective evaluation of a new device for the treatment of anal fistulas. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(30): 6936-6943

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i30/6936.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i30.6936

Surgical treatment of cryptoglandular anal fistulas remains challenging and controversial, even for experienced colorectal surgeons[1]. This condition requires individualized management because “gold-standard”does not currently exist[2]. For this reason, high success rates can only be obtained if the surgeon has in his armamentarium a wide range of therapeutic options. Moreover, the surgical choice must be balanced between the risk of faecal incontinence and that of recurrence[3]. Anal fistulotomy, fistulectomy, and endorectal advancement flaps have long been used with good healing rates but with a non-negligible risk of continence impairment[4,5]. Several minimally invasive techniques have been recently introduced to avoid any sacrifice of the sphincter complex with greatly variable results[6,7]. Among these, the placement of an anal fistula plug has been analysed in numerous studies, with acceptable results at follow up (FU). These devices aim to close the fistula tract by introducing a biomaterial into the fistula tract while sparing any sphincter disruption. Despite the initial enthusiasm and extensive use of plug technology[8-10], some frustrating results have raised doubts about the efficacy of these devices[11,12] because the overall success rate is approximately 50% or lower[13].

The primary goal of this prospective pilot study was to evaluate the safety of the implantation of a new device, the Curaseal AF™ device (CuraSeal, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, United States), for the treatment of anal fistulas. This device differs from plug technology because it acts as an internal seal to prevent enteric flow through the fistula tract. The Curaseal AF device has a specialized silicone disk that prevents continued soiling of the fistula tract during the healing process while specialized collagen promotes healing within the tract. The secondary goal of this study was to evaluate the short-term clinical efficacy of this new device.

The first ten consecutive patients treated with the Curaseal AF at our hospital were included in this analysis. All subjects were given information about the surgery and signed an inform consent form for surgical placement of the Curaseal AF device. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee (No. 12495/15).

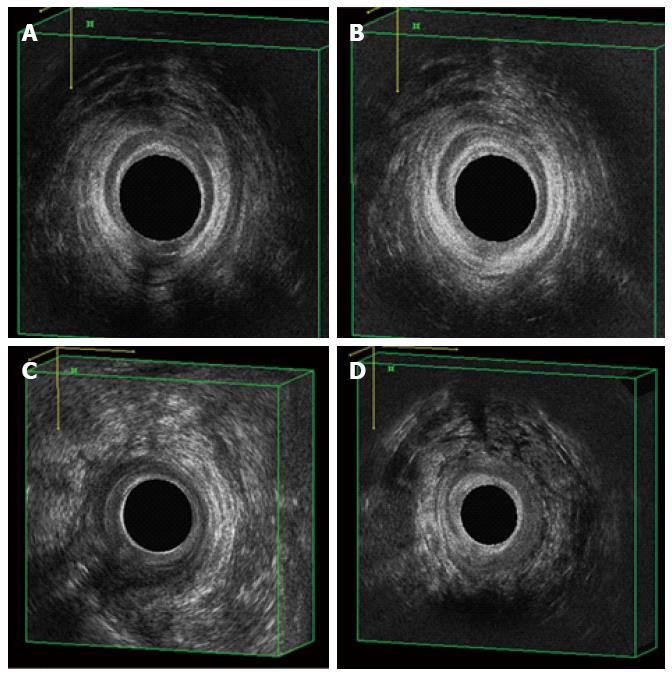

Patients affected by anal fistulas were given a full clinical and physical evaluation and assessed with an endoanal ultrasound (EAUS) performed with a 3D-US instrument (model 2202, BK Medical, Herlev, Denmark) and equipped with a 360° rotating endoprobe (model 2050, BK Medical, Herlev, Denmark). During the EAUS, in all cases, primary tracts, internal openings and possible secondary tracts, abscesses, or horseshoe tracts were evaluated.

Only patients with a complex anal fistula were prospectively enrolled to be treated with Curaseal AF™ device insertion. The following inclusion criteria were used: (1) high transphincteric fistula (tract crossing more than 30% of the external anal sphincter); (2) low transphincteric fistula only if at risk for postoperative faecal incontinence (anterior fistula in women, recurrent fistula, or history of faecal incontinence); (3) suprasphincteric fistula; or (4) extrasphincteric fistula. Patients affected by Crohn’s disease, intersphincteric or low transsphincteric fistulas, or ano- or recto-vaginal fistulas were excluded. Patients affected by acute perianal sepsis were first treated loose seton placement. After the acute sepsis was completely resolved, definitive surgery followed.

Data collected included patient demographics, fistula aetiology, fistula type, fistula age, previous fistula surgery, symptoms associated with the disease, comorbidities, smoking status, intra-operative details, and intra-operative complications.

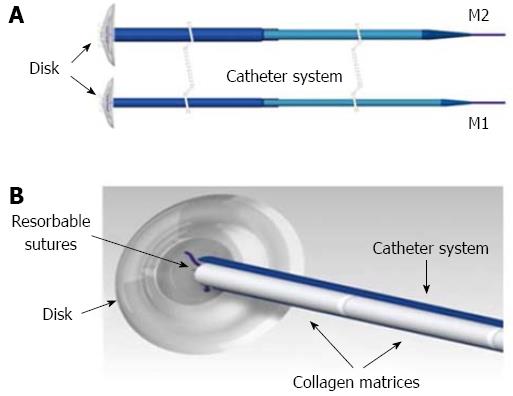

The Curaseal AF™ device is a disk of silicone with a delivery catheter containing 6 cylindrical collagen matrices. The collagen matrices provide a scaffold during the natural healing process, and the silicone disk provides an internal seal and is expelled from the anus when the resorbable sutures degrade (Figure 1). Two sizes of the Curaseal AF™ device are available: the collagen matrices and the disk of the “M1” type are smaller than those of the “M2” type (Figure 1).

Two enemas were given as bowel preparation the morning of the procedure. Antibiotics (ciprofloxacin 400 mg + metronidazole 500 mg) were administered preoperatively.

All the patients underwent the procedure in the lithotomy position under general or regional anaesthesia. All operations were performed by the same colorectal surgeon (Ratto C).

The fistula tract was cannulated with an anorectal fistula probe. During this phase, the number of internal and external openings, number of tracts, distance from the anal verge and length of the fistula tract were determined.

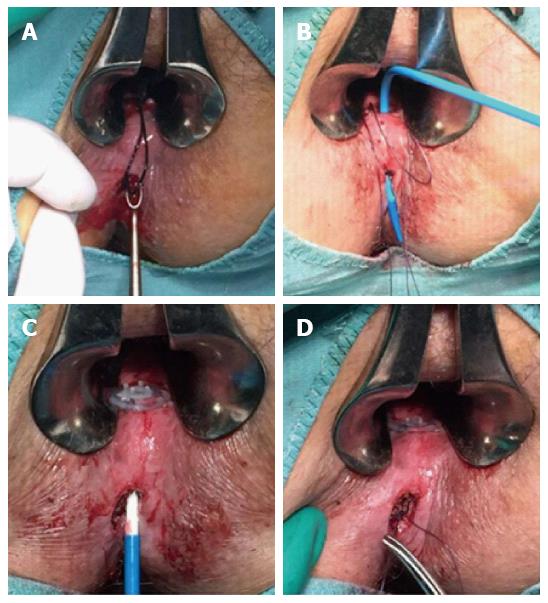

The fistula was then prepared for the Curaseal AF™ placement by cleansing and debridement of the tract to remove and clean all secondary cavities (curetting and brushing with a small endoscopic brush, irrigation of the tract with normal saline, antibiotic solution, and hydrogen peroxide) (Figure 2A). Once the tract was prepared, the Curaseal AF device was placed inside the fistula tract, passing from the internal to the external opening (Figure 2B). Once the entire device containing the collagen matrices was in the fistula tract, the external plastic cannula was removed, putting the matrices in direct contact with the fistula tract (Figure 2C). In all cases the disk was sutured to the internal opening with a single z-stich, and the proximal end of the device was sutured to the distal part of the external opening (fibrous terminal portion of the fistula tract or dermis). The external opening was left open to permit serum drainage (Figure 2D).

During the post-operative period, all patients were administered broad-spectrum antibiotics (ciprofloxacin 500 mg, 2 times/d + metronidazole 500 mg, 3 times/d for seven days); stool softeners and analgesics were also prescribed. A resting period of two weeks and a diet rich in water and fibre were also prescribed.

FU visits were scheduled at 1 and 2 wk and 1, 2, 3 and 6 mo after the operation. All patients were evaluated by clinical and physical examination and EAUS at 2 wk and 1, 2, 3 and 6 mo. Continence status was evaluated at the baseline and at the 6-mo FU visit using the Cleveland Clinic Fecal Incontinence (CCFI) score[14]. Success was defined as absence of drainage, closure of the external opening, and absence of perianal swelling or abscess formation.

From February 2015 to May 2015, ten patients underwent Curaseal AF™ placement. The male/female ratio was 7⁄3, and the median age of the patients was 65 (range, 34-84) years. The fistula was of cryptoglandular origin in all patients, with transphincteric fistulas in eight patients and extrasphincteric fistulas in the remaining two. The median fistula age was 10.5 (range, 2-60) mo (Table 1). All patients, except one, had already undergone seton placement. One patient had been subjected to a fistulotomy. Another patient had undergone an advancement of the mucosal flap and several insertions of the Surgisis® Anal Fistula Plug™ at another institution. In all cases, the disease was associated with serosanginous and pus drainage. Smell and pain were reported by seven and three patients, respectively. The most frequent co-morbidities were cardiovascular (hypertension, atrial fibrillation), and only two patients were smokers (Table 1).

| Patient No. | Gender | Age (yr) | Fistula type | Fistula age (mo) | Aetiology | Symptoms | Previous fistula surgery | Smoking | Comorbidity |

| 1 | M | 48 | Transphincteric | 2 | Cryptoglandular | Drainage, smell | Setons | Yes | Hypertension |

| 2 | F | 53 | Transphincteric | 21 | Cryptoglandular | Drainage, smell | Setons | No | Thyroiditis, celiac disease |

| 3 | M | 84 | Extrasphincteric | 9 | Cryptoglandular | Drainage, pain | Setons | No | Hypertension, diabetes |

| 4 | M | 48 | Transphincteric | 60 | Cryptoglandular | Drainage, smell | Setons, fistulotomy | Yes | None |

| 5 | M | 81 | Extrasphincteric | 8 | Cryptoglandular | Drainage, pain | Setons | No | Hypertension |

| 6 | M | 81 | Transphincteric | 36 | Cryptoglandular | Drainage, pain | - | No | Atrial fibrillation |

| 7 | M | 80 | Transphincteric | 9 | Cryptoglandular | Drainage, smell | Setons | No | Hypertension, atrial fibrillation |

| 8 | F | 34 | Transphincteric | 6 | Cryptoglandular | Drainage, smell | Setons | No | None |

| 9 | F | 71 | Transphincteric | 12 | Cryptoglandular | Drainage, smell | Setons | No | COPD, Hypothyroidism |

| 10 | M | 58 | Transphincteric | 36 | Cryptoglandular | Drainage, smell | Setons, flap, plugs | No | Gastritis |

During the study period, ten devices were placed: “M1 type” in three cases, and “M2 type” in the remaining seven. In all cases, the fistula had a single internal opening, while in three patients, two tracts were identified. The probing of the fistula tract showed that the median distance of the internal opening from the anal verge was 2 cm (range, 1.5-5 cm), while the median length of the fistula tract was 3.3 cm (range, 2.5-10 cm) (Table 2). Irrigation of the fistula tract was performed in all cases using antibiotic solution (Gentamycin) and hydrogen peroxide. Debridement by curetting plus brushing with a small endoscopic brush was performed in eight patients, and curetting plus gauze or Bovie debridement was performed in the remaining two.

| Patient No. | Device type | Distance from the a.v. (cm) | Length of the fistula tract (cm) | Internal opening, n | Fistula tracts, n | External opening, n | Size of external opening (cm) | Brushing of the tract | Irrigation of the tract |

| 1 | M2 | 2.0 | 3.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | Endoscopic brush, curette | H2O2, antibiotic |

| 2 | M2 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.1 | Endoscopic brush, curette | H2O2, antibiotic |

| 3 | M2 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.2 | Endoscopic brush, curette | H2O2, antibiotic |

| 4 | M1 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.1 | Endoscopic brush, curette | H2O2, antibiotic |

| 5 | M2 | 5.0 | 7.5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.2 | Endoscopic brush, curette | H2O2, antibiotic |

| 6 | M1 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | Endoscopic brush, curette | H2O2, antibiotic |

| 7 | M2 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | Gauze, curette | H2O2, antibiotic |

| 8 | M2 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.2 | Endoscopic brush, curette | H2O2, antibiotic |

| 9 | M1 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | Endoscopic brush, curette | H2O2, antibiotic |

| 10 | M2 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | Curette, Bovie | H2O2, antibiotic |

The entire procedure was easy to perform,even in the more complex cases (extrasphincteric fistulas, double tracts). In patients with a double tract, there was a short secondary tract lying in the perianal fat: the secondary tracts were laid opened. The median duration of the surgical procedure was 34.5 min (range, 27-42 min). No intraoperative complications were detected.

No perioperative complications occurred (including bleeding, pain, urinary retention, faecal impaction), and all patients were discharged the day after the procedure.

After 1 wk, all patients reported persistence of serum drainage, which was associated with slight pain in two cases and low-grade fever in one. At the week 2 FU visit, a failure due to device expulsion (onthe tenth postoperative day) was registered. No patient reported any type of pain, but a slight fever (37 °C) persisted in the first enrolled patient. After 1 mo, the remaining nine patients reported low serum discharge with no associated symptoms. At the 2-mo FU visit, healing and absence of discharge or abscess formation was achieved in 5 patients (50%), while low serum discharge was still reported by 3 patients (30%). At that time, a failure was registered in the first enrolled patient, with evidence of persistent inflammation around the fistula tracton the EAUS. At the 3-mo FU, healing was achieved in 2 patients (20%), while a third failure due to the persistence of serum drainage was registered. At the last FU evaluation (6 mo after surgery) no other changes occurred, resulting in a final success rate of 70% (7 out of 10 pts) (Table 3). These findings were confirmed for each patient by EAUS at 2 wk and 1, 2, 3 and 6 mo after the surgery (Figure 3). The silicone disk was expelled spontaneously after 2 wk in one patient, after 4 wk in seven, and was removed from one patient after 4 wk. No patient experienced any change incontinence, and the CCFI score was 0 both at the baseline and at the 6-mo FU visit.

| Patient No. | 1-wk follow up | 2-wk follow up | 1-mo follow up | 2-mo follow up | 3-mo follow up | 6-mo follow up |

| 1 | Slight fever (TC 37.2 °C), serum discharge | Slight fever (TC 37.0 °C), serum discharge | Low serum discharge, disk removal | Persistence of inflammation | - | Failure |

| 2 | Low serum discharge | Low serum discharge | Low serum discharge, disk absent | Healing | Healing | Success |

| 3 | Low serum discharge | Low serum discharge | Low serum discharge, disk absent | Healing | Healing | Success |

| 4 | Serum discharge | Low serum discharge | Low serum discharge, disk absent | Healing | Healing | Success |

| 5 | Serum discharge, slight pain | Serum discharge, no pain | Low serum discharge, disk absent | Low serum discharge | Healing | Success |

| 6 | Serum discharge, slight pain | Low serum discharge, disk expulsion, no pain | Serum discharge | Low serum discharge | Healing | Success |

| 7 | Low serum discharge | Low serum discharge | Low serum discharge, disk absent | Healing | Healing | Success |

| 8 | Low serum discharge | Low serum discharge | Low serum discharge, disk absent | Low serum discharge | Low serum discharge | Failure |

| 9 | Low serum discharge | Low serum discharge | Low serum discharge, disk absent | Healing | Healing | Success |

| 10 | Low serum discharge | Device extrusion | - | - | - | Failure |

Although anal fistula is a common condition in proctology with treatments that dating back many centuries[15], this problem is still a challenge, even for the most experienced colorectal surgeons today[1,2]. For many decades, anal fistulotomy was the only surgical procedure available. This procedure has excellent healing rates but with consistent worsening of postoperative continence[16]. The relatively recent addition of an immediate sphincter reconstruction has reduced this risk but has not eliminated it[17]. The oldest sphincter-saving technique is the endorectal advancement flap. Unfortunately, several studies showed that the success rate of this procedure is approximately 50%-60% in long-term FU, with a non-negligible incontinence rate of 10%-15%[5,18].

In a 2010 study of 74 patients affected by anal fistulas, when various treatment options were proposed, and the majority of the investigated patients chose a sphincter-preserving technique[19]. Therefore, other sphincter-saving procedures have been developed over the last two decades. The most attractive and well-evaluated of these procedures is the placement of a bioprosthetic anal plug[11]. The main advantages of this technique are its simplicity, repeatability, and the virtual absence of the risk of continence impairment without precluding further therapeutic interventions or subsequent surgeries.For these reasons, the major existing guidelines widely consider this approach as a potential treatment for complex anal fistulas[20,21]. However, after the publication of the initial enthusiastic evidence supporting plug technology[8,9], a progressive decline insuccess rates was documented in large population study with a long-term FU[12,13].

This study is the first to evaluate the safety and short-term efficacy of a new sphincter-saving device for treating a complex anal fistula. This specialized sealing device combines the tissue engineering aspects of a plug with a protective sealing mechanism to overcome the limitations of currently marketed plugs. The procedure for placing this device was easy to perform and relatively brief, with no observed intraoperative complications. It was also safe in the immediate post-operative period, with no perioperative complications recorded. Furthermore, all patients were discharged the day after the procedure. Although we took extra precautions because this was an early use of this new technology, it seems reasonable that this device could be used in a day surgery setting. Only two patients had mild anal pain 1 wk after surgery, but at 2 wk, none of the patient reported pain symptoms. These findings seem better than those recently reported in two studies evaluating another bio-absorbable anal fistula plug. In a retrospective study of 48 patients, Heydari et al[22] stated that at the 1-wk FU, the mean VAS score was 2.9; after 1 mo, only 23 of 28 patients reported no pain at all. Even more significantly, in a prospective multicentre study by Stamos et al[23], approximately 50% of patients complained of mild pain 1 mo after implantation, and three patients rating their the pain as severe. The reasons for the low rate and duration of pain after implantation of the new Curaseal AF™ device could be that the main part of the plug (the collagen matrices) placed within the fistula tract is soft and compliant, and in this study, the spontaneous expulsion of the silicone disk took place very early (in all cases but one).

Only one early total device extrusion was registered in this pilot study. It occurred on the tenth postoperative day. This was observed in a patient with a transphincteric fistula who had already undergone several fistula surgical interventions. Because of this chronic and recurrent clinical history, the whole fistula tract was very large, and the external orifice was the largest among the enrolled patients (Table 2). However, extrusion is a well-known complication in this type of surgery, having been reported after Surgisis® (reaching a 20%-25% rate in several studies)[11] and Gore Bio-A® Fistula Plug insertions[23].

Finally, in our first trial of this new device, we observed only one case of persistent inflammation around the fistula tract,which was observed two months after the procedure. The patient was treated by drainage and seton insertion and subsequently healed after receiving traditional fistulotomy. This complication may have been related to our inexperience using this particular device or to less aggressive preparation of the fistula tract[23,24]. However, in a meta-analysis comparing anal fistula plug and mucosal advancement flap, the complication rate, including abscess formation and bleeding, was lower when a device was inserted[25].

No other postoperative complications following the Curaseal AF™ device placement have been identified to date, and we believe that this pilot study provides further evidence of the minimally invasive nature and safety of this procedure. In addition, we also found that none of the included patients reported any symptoms of minor or major faecal incontinence in the postoperative period. Similarly, almost all studies conducted on the implantation of fistula plugs reported no changes in postoperative continence[8-12]. One exception, a recent study by Stamos et al[23] on the Gore Bio-A® Fistula Plug, demonstrated a CCFI score higher than the preoperative value in ten patients 6 mo after surgery. However, as admitted by the same authors, this could simply reflect a problem with the use of the questionnaire and with the differentiation between serous drainage from the fistula and true faecal incontinence[23]. In a randomized clinical trial and in a retrospective comparative study, the postoperative faecal incontinence rate was found to be significantly lower in patients treated with an anal fistula plug than with an endorectal advancement flap[26,27].

In addition to a low incontinence rate, a high healing rate is the major objective of any surgery to treat anal fistulas. In this pilot study, the secondary goal was the assessment of short-term clinical efficacy at the 6-mo FU. Healing was achieved in 7 out of 10 patients (70%). As studies have shown, a long FU period is needed to define a fistula as healed and not just “silent”[17,28], but it is interesting to note that in this study, the apparent healing occurred in 5 cases within two months after surgery and in another 2 cases at the 3-mo FU visit. Similarly, the three failures all occurred within the first 3 mo of FU and, moreover, no further changes, either negative or positive, were recorded between the 3-mo and 6-mo FU visit.

In a study by McGee et al[29] on another fistula plug, the success rate was higher, at the 2-year FU for fistulas with a tract longer than 4 cm (61%) than for shorter fistulas (21%). Another study showed that higher fistulas were more prone to heal[23]. The small sample size of this study did not permit the confirmation or rejection of these findings, but it is interesting to note that all three failures occurred in fistulas with a length of 3-4 cm. The two patients affected by an extrasphincteric fistula with a length of 7.5 and 10 cm, respectively, healed within 2 mo (Tables 2 and 3).

The recurrence rates for other anal fistula plugs vary in the literature[8-10,26,27], though a reasonable success rate after an anal plug placement is approximately 50%, even in the long-term FU[11]. Our results are better than those of other minimally invasive techniques. However, the small sample size and shorter FU did not allow definitive conclusions on the efficacy of this therapy to be made at this time. In a recent study, the use of an autologous cartilage plug on recurrent patients was evaluated, and the results showed a 70% success rate at the 24-mo FU visit. The main limitations of this study are the small sample size and the absence of other similar published studies. Moreover, some concerns could be raised about the collection of the cartilage by incision of the ear or nose because it could be technically demanding and not well accepted by all patients[30]. A retrospective study of L.I.F.T. published in 2013 reported a success rate of 62% at the 12-mo FU[31]. However, in another study on 93 patients, the healing rate at a median FU of 19 mo was only 40% after the first L.I.F.T. and 47% after a repeated procedure[32]. Finally, a recent systematic review of the L.I.F.T. procedure demonstrated that the level of evidence from available studies was low, showing “a mixed bag of results”. Variations in technique and FU duration preclude the possibility of establishing the true efficacy of this promising sphincter-sparing surgical option[33].

Another promising therapeutic option is the administration of mesenchymal stem cells to support healing of anal fistula related or not related to Crohn’s disease. The rationale for this option is based on the pathophysiologic process of wound healing[34].

Given the virtual absence of the risk of postoperative faecal incontinence even after L.I.F.T. procedures and stem cell administration, a randomized clinical trial comparing these techniques with other less invasive options, such as placement of the Curaseal AF device, would be useful to assess and compare their true efficacy.

In conclusion, this study on the new Curaseal AF™ device for the treatment of anal fistulas showed that the technical procedure is easy to perform, with low or absent perioperative morbidity rates. As expected, no continence impairment could be detected. The initial results after 6-mo FU seem to be promising, even in more complex cases such as extrasphincteric fistulas. However, a longer FU and a larger sample size are needed to confirm these preliminary results and assess the true efficacy of this technique. If future studies confirm these data, the placement of this implanted sealing device could play a pivotal role in the ideal algorithm of treatment of anal fistulas.

Surgical treatment of cryptoglandular anal fistulas remains controversial and, the surgical choice must be balanced between the risk of fecal incontinence and that of recurrence. To date, a “gold-standard” does not exist: the traditional fistulotomy is suitable only in case of low and “simple” fistulas, while its use is detrimental for patient’s continence in case of a more complex disease.

During the last 20 years, the progress of industry and technology in this therapeutic field led to the development of several “minimally-invasive” treatments, which aim is to heal the fistula minimizing the risk of postoperative fecal incontinence. Despite the great effort spent, at present, the obtained results are greatly variable and, sometimes, frustrating both for patient and the surgeon. For this reason the development of a safe and effective surgical treatment of anal fistula is a “hot-topic” in colorectal surgery.

This study is the first to evaluate the safety and short-term efficacy of a new sphincter-saving device for treating a complex anal fistula. This specialized sealing device combines the tissue engineering aspects of a plug with a protective sealing mechanism to overcome the limitations of currently marketed plugs. As expected, none of the implanted patients suffered of postoperative faecal incontinence at the follow-up. Moreover, no significant morbidities were registered. This is of crucial importance in the treatment of anal fistulas because the use of different therapeutic options is not precluded in the case of a treatment failure. The recurrence rates for other anal fistula plugs vary in the literature, though a reasonable success rate after an anal plug placement is approximately 50%, even in the long-term FU. This results are better than those of other minimally invasive techniques.

Given the minimally-invasive of this surgical treatment, the placement of this implanted sealing device could play a pivotal role in the ideal algorithm of treatment of anal fistulas. At present the authors implanted only patients affected by a complex anal fistula of cryptoglandular origin; future studies will assess its potential role in the treatment of other conditions, such as Crohn’s related fistulas or ano-vaginal fistulas. However, a longer FU and a larger sample size are needed to confirm these preliminary results and assess the true efficacy of this technique.

Anal fistula: an abnormal chronic communication between the anal canal and, usually, the perianal skin; Anal fistula plug: a prosthetic device (synthetic or biological) of conical shape which is introduced in the fistula tract in order to obtain both a closure of the internal anal opening and the occlusion of the tract; Cryptoglandular anal fistula: a fistula whose origin is thought to be related to infection, and then inflammation, of the glands of the anal intersphincteric space.

It is a very interesting manuscript presenting promising results of an improved plug for complex fistula treatment. Main comments were on the need for a longer follow-up period in order to evaluate the real efficacy of the technique. Furthermore, it has been suggested the use of the magnetic resonance imaging to assess the closure of the fistulous tract. Finally it has been suggested to evaluate the impact of the length of the fistula tract on the efficacy of the device, assuming that this device could be effective especially in cases with a long fistula tract.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Guadalajara H, Ozturk E S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Nicholls RJ. Fistula in ano: an overview. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2012;59:9-13. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Dudukgian H, Abcarian H. Why do we have so much trouble treating anal fistula? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3292-3296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Westerterp M, Volkers NA, Poolman RW, van Tets WF. Anal fistulotomy between Skylla and Charybdis. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:549-551. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Visscher AP, Schuur D, Roos R, Van der Mijnsbrugge GJ, Meijerink WJ, Felt-Bersma RJ. Long-term follow-up after surgery for simple and complex cryptoglandular fistulas: fecal incontinence and impact on quality of life. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:533-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Soltani A, Kaiser AM. Endorectal advancement flap for cryptoglandular or Crohn’s fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:486-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Limura E, Giordano P. Modern management of anal fistula. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:12-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Lewis R, Lunniss PJ, Hammond TM. Novel biological strategies in the management of anal fistula. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:1445-1455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Johnson EK, Gaw JU, Armstrong DN. Efficacy of anal fistula plug vs. fibrin glue in closure of anorectal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:371-376. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Buchberg B, Masoomi H, Choi J, Bergman H, Mills S, Stamos MJ. A tale of two (anal fistula) plugs: is there a difference in short-term outcomes? Am Surg. 2010;76:1150-1153. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Ratto C, Litta F, Parello A, Donisi L, Zaccone G, De Simone V. Gore Bio-A® Fistula Plug: a new sphincter-sparing procedure for complex anal fistula. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e264-e269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | de la Portilla F, Rada R, Jiménez-Rodríguez R, Díaz-Pavón JM, Sánchez-Gil JM. Evaluation of a new synthetic plug in the treatment of anal fistulas: results of a pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1419-1422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ortiz H, Marzo J, Ciga MA, Oteiza F, Armendáriz P, de Miguel M. Randomized clinical trial of anal fistula plug versus endorectal advancement flap for the treatment of high cryptoglandular fistula in ano. Br J Surg. 2009;96:608-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | O'Riordan JM, Datta I, Johnston C, Baxter NN. A systematic review of the anal fistula plug for patients with Crohn’s and non-Crohn’s related fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:351-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:77-97. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Tsamis D. The origin of cure for fistula in ano: technique of Hippocrates. Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19:489-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Göttgens KW, Janssen PT, Heemskerk J, van Dielen FM, Konsten JL, Lettinga T, Hoofwijk AG, Belgers HJ, Stassen LP, Breukink SO. Long-term outcome of low perianal fistulas treated by fistulotomy: a multicenter study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:213-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ratto C, Litta F, Donisi L, Parello A. Fistulotomy or fistulectomy and primary sphincteroplasty for anal fistula (FIPS): a systematic review. Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19:391-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mizrahi N, Wexner SD, Zmora O, Da Silva G, Efron J, Weiss EG, Vernava AM, Nogueras JJ. Endorectal advancement flap: are there predictors of failure? Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1616-1621. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Ellis CN. Sphincter-preserving fistula management: what patients want. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1652-1655. |

| 20. | Steele SR, Kumar R, Feingold DL, Rafferty JL, Buie WD. Practice parameters for the management of perianal abscess and fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1465-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ommer A, Herold A, Berg E, Fürst A, Sailer M, Schiedeck T. Cryptoglandular anal fistulas. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:707-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Heydari A, Attinà GM, Merolla E, Piccoli M, Fazlalizadeh R, Melotti G. Bioabsorbable synthetic plug in the treatment of anal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:774-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Stamos MJ, Snyder M, Robb BW, Ky A, Singer M, Stewart DB, Sonoda T, Abcarian H. Prospective multicenter study of a synthetic bioabsorbable anal fistula plug to treat cryptoglandular transsphincteric anal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:344-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Garg P, Song J, Bhatia A, Kalia H, Menon GR. The efficacy of anal fistula plug in fistula-in-ano: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:965-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Leng Q, Jin HY. Anal fistula plug vs mucosa advancement flap in complex fistula-in-ano: A meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;4:256-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | A ba-bai-ke-re MM, Wen H, Huang HG, Chu H, Lu M, Chang ZS, Ai EH, Fan K. Randomized controlled trial of minimally invasive surgery using acellular dermal matrix for complex anorectal fistula. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3279-3286. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Christoforidis D, Pieh MC, Madoff RD, Mellgren AF. Treatment of transsphincteric anal fistulas by endorectal advancement flap or collagen fistula plug: a comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:18-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | van der Hagen SJ, Baeten CG, Soeters PB, van Gemert WG. Long-term outcome following mucosal advancement flap for high perianal fistulas and fistulotomy for low perianal fistulas: recurrent perianal fistulas: failure of treatment or recurrent patient disease? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:784-790. [PubMed] |

| 29. | McGee MF, Champagne BJ, Stulberg JJ, Reynolds H, Marderstein E, Delaney CP. Tract length predicts successful closure with anal fistula plug in cryptoglandular fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1116-1120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ozturk E. Treatment of recurrent anal fistula using an autologous cartilage plug: a pilot study. Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19:301-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Liu WY, Aboulian A, Kaji AH, Kumar RR. Long-term results of ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) for fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:343-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wallin UG, Mellgren AF, Madoff RD, Goldberg SM. Does ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract raise the bar in fistula surgery? Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:1173-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Sirany AM, Nygaard RM, Morken JJ. The ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract procedure for anal fistula: a mixed bag of results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:604-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Garcia-Olmo D, Schwartz DA. Cumulative Evidence That Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Healing of Perianal Fistulas of Patients With Crohn’s Disease--Going From Bench to Bedside. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:853-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |