INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD) is a recently developed alternative to percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) for patients in whom endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has failed. There are many reports regarding the safety, feasibility, and clinical efficacy of EUS-BD. Quite recently, new types of stents modified for EUS-BD were developed. EUS-BD includes EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy (EUS-CDS), EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy (EUS-HGS), EUS-guided hepaticoenterostomy (EUS-HES) and EUS-guided rendezvous (EUS-RV), among others. The intrahepatic and extrahepatic approaches are quite different with respect to indications, techniques, and complications. However, many reports include analysis of the combined results of intrahepatic and extrahepatic approaches. Therefore, specific details of when and how EUS-guided biliary drainage should be performed, and which procedure should be used, remain somewhat unclear. In this review, we discuss an EUS-BD algorithm for treatment of inoperable malignant lower biliary obstruction.

WHO SHOULD PERFORM EUS-BD?

EUS-BD is technically difficult and, currently, complications rates are high, so only endoscopists skilled in both EUS and ERCP should perform EUS-guided biliary and pancreatic drainage procedures.

EUS-guided drainage should not be used to compensate for a lack of ERCP skills[1]. EUS-BD is not a mature technique because of the current lack of dedicated devices. If trainees would like to perform EUS-BD safely and successfully, they should begin by participating in procedures such as EUS-guided cystogastrostomy or various EUS-guided drainage techniques under a mentor’s supervision[1]. A Spanish national survey of EUS-BD revealed success rates for EUS-HGS, EUS-CDS and EUS-rendezvous of 64.7%, 86.3% and 68.3%, respectively[2]. From that survey, it was reported that a total of 4 perforations were caused by inward stent migration after hepaticogastrostomy (12%, 4/34) and 5 (4%) patients died, 2 of them as a consequence of bile peritonitis, 2 after perforation, and 1 after massive intraperitoneal bleeding. However, all endoscopists in the Spanish survey were beginners at relatively low-volume centers, with an average experience of < 20 EUS-BD procedures in total. These results seem to provide more realistic clinical data without publication bias from general hospitals[3]. Even for skillful endoscopists, we recommend learning EUS-BD under a mentor’s supervision for at least the first 20 cases. Recently, an animal model and a 3D printing model for EUS-BD were reported. These models may help trainees become skilled in EUS-guided procedures[4,5].

WHEN SHOULD WE PERFORM EUS-BD?

Normal anatomy

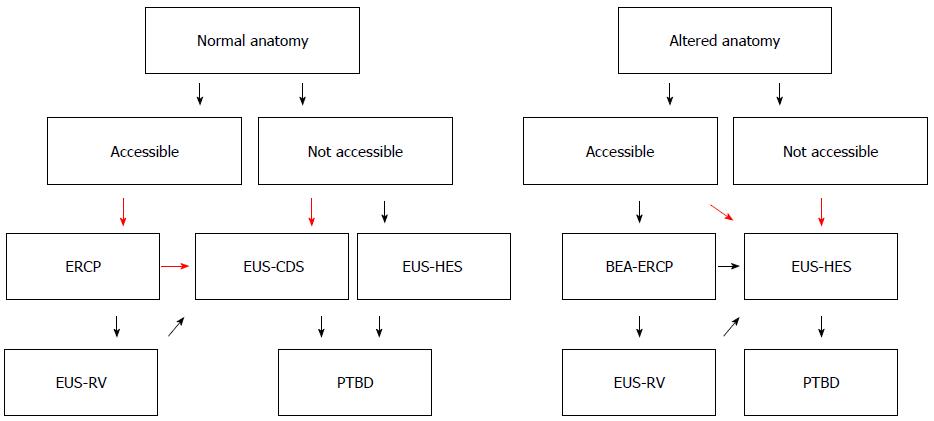

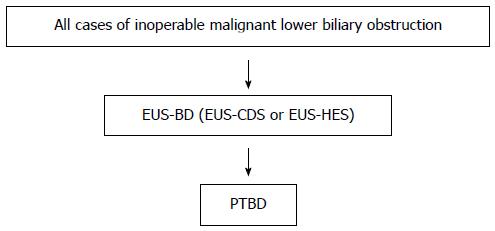

We present an EUS-BD algorithm for inoperable malignant lower biliary obstruction in Figure 1. This algorithm is proposed for use by experts in EUS-BD.

Figure 1 Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage algorithm for inoperable malignant lower biliary obstruction.

Flow chart for management of inoperable malignant lower biliary obstruction. This algorithm is proposed for use by experts in endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage. Our recommendations are large red arrows.

Our recommendations are large red arrows. After failed ERCP, which procedure should we perform? Some authors reported the superiority of EUS-BD over PTBD[6-8]: Artifon et al[8] reported similar technical and clinical success rates, complications rates and costs for both groups. Bapaye et al[7] reported the superiority of EUS-BD for success and complications rates compared to PTBD. Khashab et al[6] reported that technical success was higher in the PTBD group (100% vs 86.4%, P = 0.007), and that clinical success was equivalent (92.2% vs 86.4%, P = 0.40). They also found a higher adverse event rate and a significantly higher rate of re-interventions with PTBD. According to these reports, EUS-BD and PTBD have similar success rates and similar efficacy, although the complications rate is somewhat higher for PTBD. EUS-BD results in better QOL for patients because there is no external drainage. EUS-BD is recommended over PTBD by the results of these previous reports.

How about EUS-RV? EUS-RV is also a useful procedure[9-14], but there are some limitations. Most importantly, there is a lower success rate compared to EUS-BD and PTBD. Passing the guidewire through the malignant stricture is sometimes difficult. Isayama et al[12] reported that the overall success rate of EUS-RV in 247 cases from 7 published reports was 74% and the incidence of complications was 11%. Iwashita et al[9] reported that the overall success rate was 80% (16/20) and minor adverse events occurred in 15% of patients (3/20). Even if EUS-RV has failed, EUS-BD can be successfully performed. Perez-Miranda et al[10] reported on performing EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy with a lumen-apposing metal stent after failed rendezvous. According to these papers, EUS-BD is superior to EUS-RV for success rate and procedure time, and the complications rates are similar. EUS-BD is recommended before EUS-RV for inoperable malignant cases. EUS-RV is better for patients with benign conditions - for example, for stone removal.

Altered anatomy

Recently, balloon-enteroscope-assisted ERCP (BEA-ERCP) has been described as a remarkable and useful procedure for patients with altered anatomy, and is recommended for these situations, but there are some limitations[15-18]. Insertion of the BEA-scope is sometimes difficult and dangerous for patients with malignant disseminated disease, and re-intervention using BEA-ERCP is also difficult if the patient’s condition was worsened by dissemination. In addition, biliary cannulation and EST is sometimes difficult. Moreover, the working channel of the BEA-scope is too small for complicated treatments, for example, those requiring multiple-guidewire and multiple-stenting techniques[15,19]. Inamdar et al[17] reported that the pooled enteroscopy, diagnostic, and procedural success rates were 80.9% (95%CI: 75.3%-86.4%), 69.4% (95%CI: 61.0%-77.9%), and 61.7% (95%CI: 52.9%-70.5%), respectively. According to previous reports, the procedural success is slightly lower compared to the EUS-guided approach, especially for malignant biliary obstruction. BEA-ERCP is usually useful for benign disease, not inoperable malignant biliary obstruction.

How about EUS-BD for altered anatomy situations? Siripun et al[20] reported that the pooled technical success, clinical success, and complications rates for EUS-BD in all reports with available data for altered anatomy patients were 89.18%, 91.07% and 17.5%, respectively. A high success rate is reported for EUS-BD compared to BEA-ERCP. EUS-BD is superior to BEA-ERCP for treatment success rate and procedure time. Therefore, it is recommended that a skillful endosonographer perform EUS-BD, and not BEA-ERCP, in cases of altered anatomy and inoperable malignant lower biliary obstruction.

WHICH PROCEDURES SHOULD WE PERFORM FOR INOPERABLE MALIGNANT LOWER BILIARY OBSTRUCTION?

Results of EUS-BD

We already mentioned the superiority of EUS-BD over EUS-RV for patients with malignancies. Now we will consider direct transluminal stent placement. Novel techniques include EUS-CDS and EUS-HGS for inoperable malignant lower biliary obstruction. If the duodenal bulb is obstructed by tumor invasion, we have to select EUS-HGS. Pancreatic cancer sometimes causes obstructive jaundice and duodenal obstruction. However, pancreatic cancer usually involves the 2nd part of the duodenum, not the duodenal bulb. If both procedures are available; which is better, EUS-CDS or EUS-HGS?

Three multicenter studies and one prospective, randomized trial comparing EUS-CDS and EUS-HGS were reported[21-24]. Dhir et al[24] reported that complications were significantly higher for the transhepatic route compared to the transduodenal route (30.5% vs 9.3%, P = 0.03) and there was no significant difference in success rates for the different techniques. Gupta et al[23] reported similar success rates (84.3% vs 90.4%, P = 0.15) and similar complications rates (32.6% vs 35.6%, P = 0.64) for extrahepatic and intrahepatic approaches, respectively. Kawakubo et al[22] reported that the stent dysfunction rate and 3-mo dysfunction-free patency rate were, respectively, 21% and 80% for EUS-CDS and 32% and 51% for EUS-HGS.

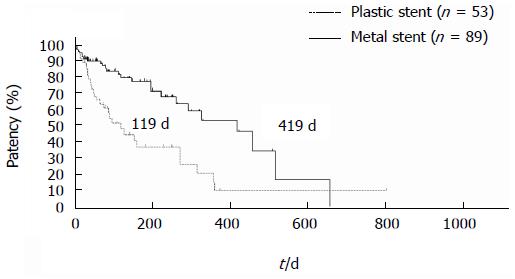

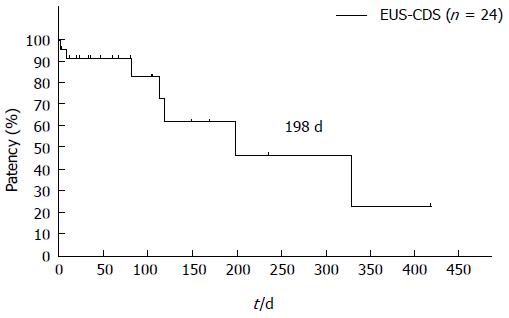

The dysfunction rate of EUS-HGS is higher than that of EUS-CDS. Artifon et al[21] reported that EUS-HGS and EUS-CDS have similar safety and efficacy in a prospective, randomized trial. According to multicenter studies and a prospective, randomized trial, EUS-CDS and EUS-HGS are both useful procedures, but EUS-HGS has a higher complications rate and higher dysfunction rate than does EUS-CDS. EUS-HGS plus antegrade stenting through the papilla was reported to prevent frequent dysfunction[25,26]. EUS-HGS has the wonderful benefit of not causing pancreatitis, but antegrade stenting is a risk for pancreatitis. Pancreatitis is a severe and sometimes fatal complication, which should be avoided. Stent patency is not well described in the literature because follow-up periods or survival times have been comparatively short. Our original prospective follow-up data shows that the patency following EUS-CDS is long, especially for metal stents. The median patency of a metal stent following EUS-CDS is 419 d, as shown in Figure 2. Some doctors recommend EUS-HGS for cases requiring double stenting (duodenal and biliary). But our prospective follow-up results reveal prolonged biliary stent patency, as shown Figure 3; the median patency following EUS-CDS involving double stenting is 198 d. According to our data, we recommend EUS-CDS over EUS-HGS even if double stenting is required.

Figure 2 Stent patency in endoscopic ultrasonography-guided choledochoduodenostomy patients.

Median stent patency in endoscopic ultrasonography-guided choledochoduodenostomy patients patients was 119 days for plastic stents and 419 d for metal stents. Logrank: HR = 0.3888, 95%CI: 0.19453-0.61081, P < 0.001.

Figure 3 Patency of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided choledochoduodenostomy after double stenting.

After double stenting, median choledochoduodenostomy patency was 198 d. EUS-CDS: Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided choledochoduodenostomy.

Complication

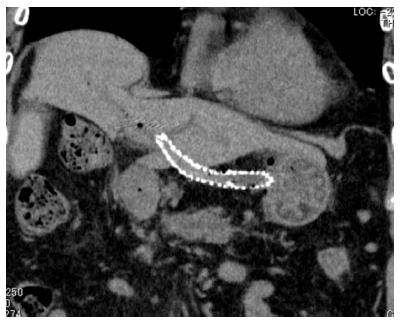

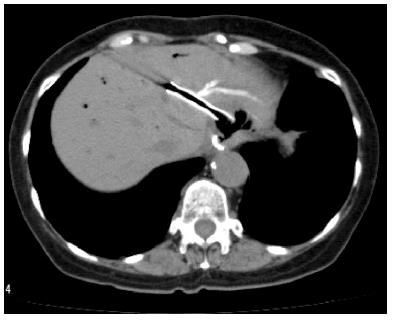

EUS-BD has many potential of complications. Common complications are bile peritonitis, perforation, bleeding and pneumoperitoneum. Internal stent migration is a severe complication of EUS-HGS[27,28]. A fatal case has been reported[28]. Usually, the liver and stomach are not adhered; there is a wide space between the two organs, as shown Figure 4. Liver abscess, biloma[29], focal cholangitis, pseudoaneurysm[30] and bile duct obstruction caused by hyperplasia are also unique complications of EUS-HGS, as shown in Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7. Figure 5 is the focal cholangitis, Figure 6 is the liver abscess, and Figure 7 is the bile duct stenosis caused by hyperplasia. All complications of Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 were caused by the large bore metal stent in EUS-HGS. If we avoid these complications, we should select a small bore stent. But, a small bore stent as a plastic stent is usually short stent patency and has the comparatively high risk of bile leakage. EUS-HGS has many more types of complications than EUS-CDS.

Figure 4 Stent migration into abdominal cavity.

There is wide space between the liver and stomach in some cases.

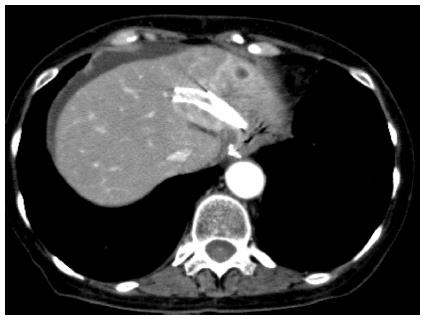

Figure 5 Focal cholangitis due to endoscopic ultrasonography-guided hepaticogastrostomy.

Two days after endoscopic ultrasonography-guided hepaticogastrostomy, focal cholangitis occurred after blockage of the peripheral bile duct by the metal stent.

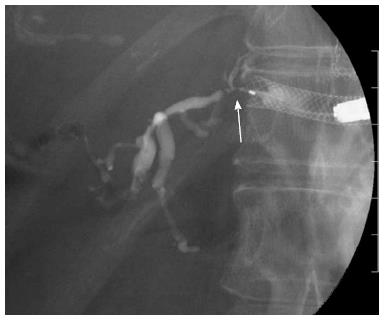

Figure 6 Liver abscess due to endoscopic ultrasonography-guided hepaticogastrostomy.

Liver abscess occurred after blockage of the peripheral bile duct by the metal stent.

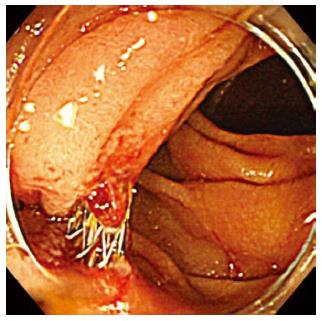

Figure 7 Bile duct stenosis caused by hyperplasia.

Hyperplasia caused by placement of a metal stent that was too large for the peripheral bile duct.

A unique complication of EUS-CDS is double penetration of the duodenum in Figure 8. After EUS-CDS using the oblique view, double penetration of the duodenum was seen in 4% (4/101) of our prospective follow-up patients. Double penetration of the duodenum may cause retroperitoneal perforation.

Figure 8 Double penetration of the duodenum.

Double penetration of the duodenum is a unique complication of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided choledochoduodenostomy that is performed using the oblique view.

EUS-CDS and EUS-HGS are similar procedures, but their complications are quite different. Re-intervention methods for both techniques are also different. Therefore, we should understand the differences between these procedures in detail.

HOW TO PERFORM EUS-BD

Standard procedures for performing EUS-BD are similar: Puncture the bile duct, dilate the tract, and place the stent. The most difficult point is dilation of the fistula. Many beginners have experienced failed dilation. The electric cautery coaxial dilator is a most useful device for dilation[31]: when used, successful dilation of the fistula can be achieved very quickly and very easily. It is sometimes more difficult to dilate the tract during EUS-CDS compared to EUS-HGS. The coaxial dilator is recommended for EUS-CDS to increase the success rate.

Prachayakul et al[32] reported that the use of a needle-knife for fistula dilation in EUS-BDS should be avoided if possible. The needle-knife is not coaxial, so its use is accompanied by a high risk of complications. You can usually dilate the tract in EUS-HGS; because this occurs against the background of the liver, the power required to dilate is easily transmitted to the tract. We recommend use of a tapered catheter during EUS-HGS, for safety.

Which is better, forward-viewing EUS (FV-EUS) or oblique-viewing EUS (OV-EUS)? We have reported the usefulness of FV-EUS for EUS-CDS. The needle direction with respect to the duodenal wall is perpendicular using FV-EUS, so we can easily puncture and then dilate the tract, easily place the stent, and easily prevent double penetration of the duodenum. But, using FV-EUS for EUS-HES is very difficult, and we do not recommend it.

Which stent is better? Kawakubo et al[22] reported that bile leakage was more frequently observed in patients who underwent plastic stent placement (11%) than in those receiving covered metal stents (4%). So, the covered stent is recommended for EUS-BD. Recently, a newly-designed covered metal stent was developed[5,30,33-36]. A lumen-apposing self-expanding metal stent that can decrease bile leakage is currently the dedicated device for EUS-BD. Use of a lumen-apposing self-expanding metal stent for EUS-CDS or EUS-gallbladder drainage was recently reported. But, until recently, no one knew which stent was actually the best for EUS-BD. As of now, we know that the covered metal stent is safest for EUS-BD, and the longer stent is safest for EUS-HGS, although further studies may reveal that the anti-migration system and lumen-apposing system may be even better.

EUS-BD ALGORITHM FOR INOPERABLE MALIGNANT LOWER BILIARY OBSTRUCTION, FOR NOW AND USE IN THE NEAR FUTURE

Our proposed strategy for treatment of inoperable malignant lower biliary obstruction is shown in Figure 1. The algorithm shown in Figure 9 is not suitable for application now; it applies to the near future. If a unique dedicated device for EUS-BD is developed, we can surely increase the success rate and decrease the complications rate. Compared to ERCP, a short operative time is required. We can prevent severe or fatal complications, and of course there is no fear of pancreatitis. We seriously believe that EUS-BD will prove to be superior to ERCP, and that EUS-BD will become the first-line choice for biliary drainage in the near future[37,38], as shown Figure 9.

Figure 9 Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage algorithm for management of inoperable malignant lower biliary obstruction suggested for the near future.

Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage will be first-line biliary drainage method instead of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, in our opinion. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage will persist as the last-resort procedure. EUS-BD: Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage; EUS-CDS: Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided choledochoduodenostomy; EUS-HES: Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided hepaticogastrostomy; PTBD: Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage.

CONCLUSION

EUS-BD is sometimes a dangerous procedure; only endoscopists skilled in both ERCP and EUS should be permitted to perform EUS-BD. We should select EUS-BD for treatment of inoperable malignant lower biliary obstruction before EUS-RV and PTBD, according to published data.

For patients with altered anatomy, EUS-BD is recommended before BEA-ERCP. EUS-CDS is recommended if both EUS-CDS and EUS-HGS are available. In the near future in high-volume centers, EUS-BD will become the first-line treatment for biliary drainage, replacing ERCP.

P- Reviewer: Matsubayashi H, Pellicano R, Teoh AYB S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM