INTRODUCTION

Traditionally, the standard treatment for early gastric cancer (EGC) is surgery. However, more recently, endoscopic resection (ER) has become a standard local treatment for some patients with EGC who lack lymph node metastasis (LNM)[1]. Initially, ER was used to treat differentiated-type EGC (D-EGC) with a < 2-cm-diameter tumor confined to the mucosa[2-4]. Today, the indications for ER have been expanded in many studies to even include undifferentiated-type EGC (UD-EGC) with ≤ 2-cm-diameter without either ulceration or lymphovascular invasion[5]. Such indications are used to decide on both the feasibility before and curability after ER. If curability is considered doubtful, additional surgery should be performed. Many studies have explored the feasibility and effectiveness of ER to treat UD-EGC[6-10].

However, gastric cancers exhibiting undifferentiated-type histology exhibit biological behaviors differing from those of D-EGC. The former cancers are characterized by higher frequencies of both LNM and infiltrative growth[11]. Thus, any decision to employ ER of UD-EGC must be very carefully made. The present review emphasizes the points that must be considered.

HISTOLOGICAL DIAGNOSIS OF UD-EGC PRIOR TO ER

Histological diagnosis prior to treatment is important, especially if ER is contemplated. Furthermore, a change from D-EGC status on prior biopsy to UD-EGC status at the time of ER is critical in terms of a decision to perform additional surgery after ER and to predict prognosis[12]. In previous studies, about 15% to 18% of patients with UD-EGC diagnosed after ER exhibited differentiated histology on biopsy prior to ER[12,13]. A tumor diameter of > 2 cm and bodily location predict the histological features of UD-EGC[12-14]. A UD-EGC exhibiting differentiated histology on earlier biopsy is more aggressive and associated with a lower curative resection rate than is a UD-EGC, consistent with the biopsy pathologies[12-14]. When precise histological diagnosis prior to ER is required, magnifying endoscopy (ME) with narrow-band imaging (NBI) is helpful. Additionally, the actual biopsy site may be more important than the number of biopsies taken. A previous study featuring histopathological mapping and evaluation of the endoscopic appearance of UD-EGCs that exhibited differentiated histology on prior biopsy found that the zone of transition from differentiated to undifferentiated-type histology frequently occurred in one or two peripheral regions of the lesion[12]. Thus, biopsy of several peripheral regions may aid in the diagnosis of undifferentiated-type histology prior to ER[12].

UNDIFFERENTIATED-TYPE HISTOLOGY AND ER OF EGCS

The risk of LNM is the most important factor to consider when contemplating ER of EGCs[7]. Thus, the indications for ER are the absence of risk factors associated with LNM and include consideration of the histological status of the EGC. The relevant histological classifications include those of the World Health Organization (WHO), Lauren, and Japanese experts[1,7,15,16]. Many studies have found that the biological behaviors of EGC vary according to histological differentiations[17,18].

ER has been performed with reference to the Japanese classification, which simply categorizes patients with EGC into those with differentiated or undifferentiated-type histology. In this classification, undifferentiated adenocarcinoma[19] is a cancer that lacks glands and includes poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (PDA), signet ring cell carcinoma (SRC), and mucinous adenocarcinoma (MA) (as does the WHO system). PDA and MA are associated with higher LNM rates than are EGCs of other histological types, and the SRC form of EGC is associated with relatively less LNM than are EGCs of other histologies[20-23]. Thus, biological behaviors such as LNM differ among the histopathological subtypes of UD-EGC.

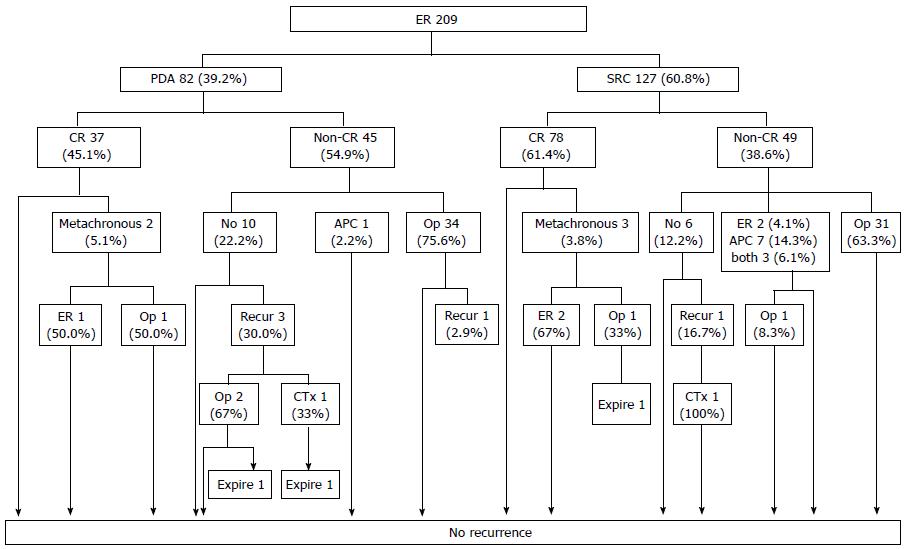

However, when ER is performed with reference to current indications, the clinical outcomes of PDA and SRC patients do not differ significantly[6,10]. The first report on the use of ER to treat UD-EGCs of various histological subtypes found no instance of either local recurrence or distant metastasis in patients with either PDA or SRC if curative resection (CR) was attained[10]. This result was validated on long-term follow-up (Figure 1)[6]. Therefore, the current criteria for CR of UD-EGC can be applied to both patients with PDA and those with SRC, who enjoy good long-term outcomes.

Figure 1 Follow-up outcomes after endoscopic resection of undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer.

The numbers in the boxes are the numbers of cases. CR: Curative resection; PDA: Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma; SRC: Signet ring cell carcinoma; APC: Argon plasma coagulation; ER: Endoscopic resection. Taken with permission from Surg Endosc 2014; 28: 2627-2633[6].

The current indications for ER do not include EGC of mixed histology. As mentioned above, the Japanese classification categorizes EGCs into only gastric cancers of differentiated or undifferentiated-type histology. However, many studies have found that EGCs of mixed histologies exhibit more aggressive clinicopathological behaviors than do EGCs of non-mixed histologies[18,24-26]. We also found that SRC mixed histology, defined as an adenocarcinoma with a minor component less than 50% of the SRC, is associated with more LNM than are EGCs of other histologies[18]. We therefore explored the clinicopathological behaviors of EGCs of mixed histology to determine whether new ER criteria are required (manuscript submitted). We measured LNM rates by all recognized types of mixed histology as follows: (1) the mixed type as non-homogenous mixtures of the Lauren classification; (2) the mixed type of the Lauren classification divided into the differentiated dominant and the undifferentiated dominant mixed types[24]; and (3) SRC mixed histology identified in our previous study[18]. As found previously, the LNM rates were higher in patients with EGC with all types of mixed histology than in those with pure types of EGC. When analyzing within the current ER criteria, however, LNM was not observed. Thus, this need for new criteria when ER is contemplated for patients with EGCs of mixed histologies has not been identified until now. Further studies are required. Two prior works reported different outcomes after ER of EGCs of mixed histology[27,28]. One found a lower CR rate and more local recurrence after ER of EGCs of mixed than pure histology[27]. However, the other study reported favorable long-term outcomes (including the absence of LNM and extragastric recurrence) during follow-up after ER of EGCs of mixed histology that met the curative ER criteria[28].

ER OF UNDIFFERENTIATED-TYPE EGCS

If CR is attained, the long-term outcomes after ER of UD-EGC are favorable in terms of local recurrence, LNM, distant metastasis, and survival[6,29-32]. However, the CR rates have historically been low (30%-80%)[6,10,29,30,32-34]. The principal reason why the CR rate differs between PDA and SRC (although the long-term outcomes do not)[6,10] is that non-CR is associated with a vertical cut-end positive status in patients with PDA and a lateral cut-end positive status in patients with SRC[6,10].

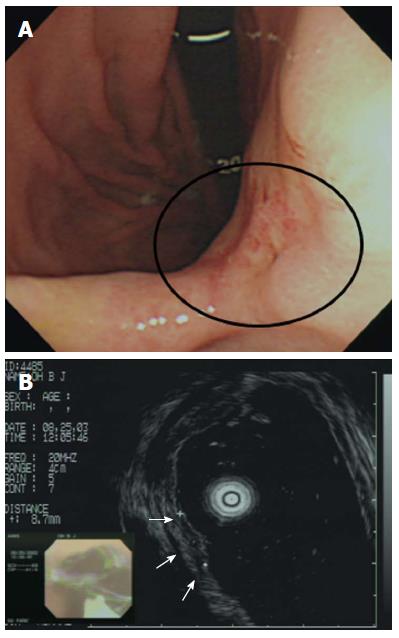

In terms of non-CR of PDA, prediction of tumor depth before treatment is difficult. Although pretreatment evaluation via endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) may suggest that the lesions are confined to the mucosa, the lesions may in fact have attained the submucosa (Figure 2)[10,35]. Such observations suggest that pretreatment EUS evaluation of the invasion depth may often underestimate such depth in patients with PDA, consistent with data of a previous study in which PDA histological features were significantly associated with understaging of the invasion depth upon multivariate analysis[10,35]. Therefore, the possibility of depth underestimation upon EUS should be considered prior to ER of PDA. Strict EUS criteria for submucosal invasion should be established to avoid T-stage underestimation for achieving CR in PDA[10,35].

Figure 2 Incorrect T staging: a case of undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer (EGC).

A: Endoscopic image of an EGC showing a 10-mm-diameter depressed lesion in the posterior angle of the wall; B: Endoscopic ultrasonographic image showing a hypoechoic mucosal mass with an intact submucosal layer. A surgical specimen obtained upon radical subtotal gastrectomy confirmed that the EGC was confined to the submucosal layer. Taken with permission from Gastrointest Endosc 2007; 66: 901-908[35].

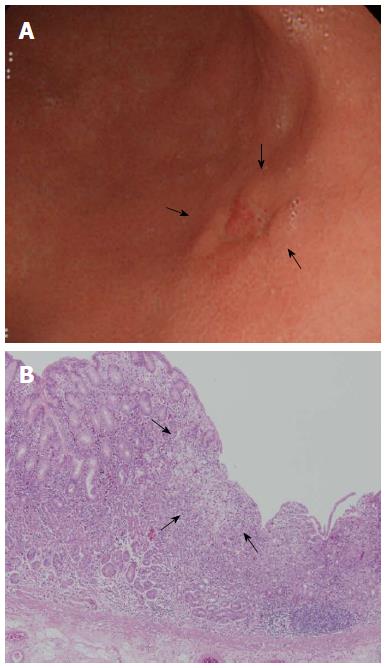

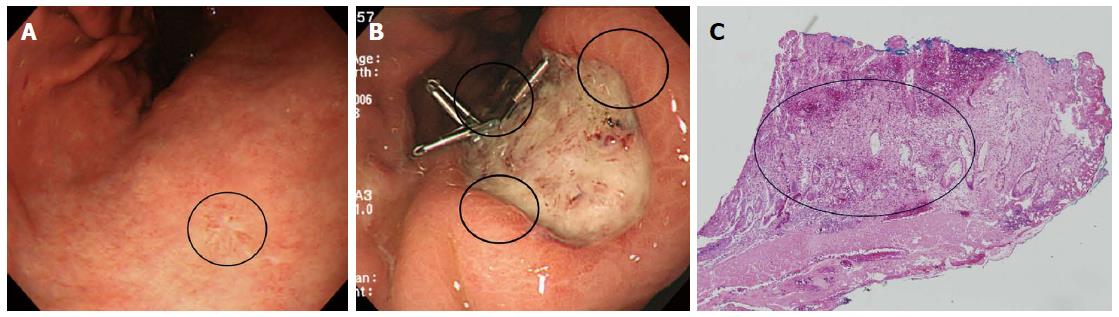

With respect to non-CR of SRC, it is difficult to define the extent of the lesion. ME with NBI has been used in efforts to precisely define the lateral extent of EGC[6,36,37]. However, several studies found that such predictions were inaccurate in patients with UD-EGC, but not in those with D-EGC[6,37,38]. Yao et al[38] suggested that the strategy should vary by the histological type of EGC (D- vs UD-EGC). For the latter type of tumor, the margins should be determined by biopsy of apparently non-cancerous tissue surrounding the lesion and histological confirmation of the absence of any cancerous invasion[38]. In other words, it is difficult to precisely define the lateral margins of UD-EGCs; pathological confirmation is required. Surface ME with NBI will not detect any cancer-specific, irregular microvascular or microsurface pattern if the cancer cells have infiltrated the lamina propria, perhaps to the depth of the glandular neck[38]. The origin of SRC reportedly differs from that of other gastric adenocarcinomas[39]. Tubule neck dysplasia (TND) may be a precursor lesion of SRC[39]. TND can spread upward toward the foveolar surface and possibly downward to the gastric glands[39]. Thus, the gastric mucosal surface epithelium in patients with early-stage SRC may appear to be largely intact despite the presence of cancer cells in the lamina propria. It may be useful to define ER subgroups of SRC based on intramucosal spreading patterns such as epithelial spread, and not simply to determine resection margins via endoscopy or biopsy. Indeed, we examined the intramucosal spreading patterns of the SRC type of EGC reported previously, and identified (for example) both expanding (epithelial spread) and infiltrative (subepithelial spread) subtypes[11]. The proportion of infiltrative spread was higher in lateral cut-end-positive than -negative early-stage SRCs (Figures 3 and 4)[40]. We also found that the surrounding mucosal pattern was useful to define the type of intramucosal spread in early-stage SRCs (Figures 3 and 4)[40]. The mucosa surrounding infiltrative lesions more commonly exhibited atrophy and intestinal metaplasia[40], indicating that the mucosa may be an important mechanical barrier to tumor spread in patients with early-stage SRC[40]. This is in line with the fact that diagnosis of the extent of an undifferentiated-type lesion against a background of severe mucosal atrophy is quite difficult, even with ME/NBI[41-43]. Therefore, larger ER safety margins may be necessary if early-stage SRCs are surrounded by mucosa exhibiting atrophy or/and intestinal metaplasia, which often spreads sub-epithelially to the margins[40].

Figure 3 Clinical example of signet ring cell carcinoma exhibiting expansive intramucosal spread.

A: An endoscopic image of early gastric cancer (EGC) showing a depressed lesion located in the posterior wall of the lower body. Endoscopically, the surrounding mucosa did not exhibit atrophy or intestinal metaplasia; B: Pathological findings after endoscopic resection (× 40). SRC tumor cells were superficially exposed in a mucosal region and were well-demarcated (arrow). Taken with permission from Gut Liver 2015; 9: 720-726[40].

Figure 4 Clinical example of the signet ring cell carcinoma associated with infiltrative intramucosal spread.

A: An endoscopic image of an EGC, showing a flat lesion located in the lesser curvature of the lower body (circle). Endoscopically, the surrounding mucosa exhibited atrophic gastritis; B: After endoscopic resection, three of the lateral margins were positive (circle); C: Pathological findings after endoscopic resection (× 40). Signet ring cell carcinoma cells exhibited subepithelial spread. In other words, the lesion was of the infiltrative type (circle). Taken with permission from Gut Liver 2015; 9: 720-726[40].

Thus, to be curatively resected by ER in UD-EGC, it is important to consider the biological characteristics of UD-EGC and not simply to perform advanced endoscopy such as ME with NBI. Again, UD-EGC differs from D-EGC[6].

Undifferentiated histology is the principal risk factor for the presence of residual tumor cells after complete resection of EGC[44]. PDA, SRC, and a minimum lateral safety margin of < 3 mm are significantly associated with residual tumors[44]. Short-term endoscopic follow-up with close examination of the resected base may reveal a residual tumor although CR of UD-EGC is histologically evident[44].

A negative lateral margin (i.e., a margin free of cancerous cells) is very important in the context of CR. However, no consensus has emerged on the extent of this margin. A lateral margin of > 3 mm may increase the success rate of CR[44]. Further studies of patients with PDA and SRC are required.

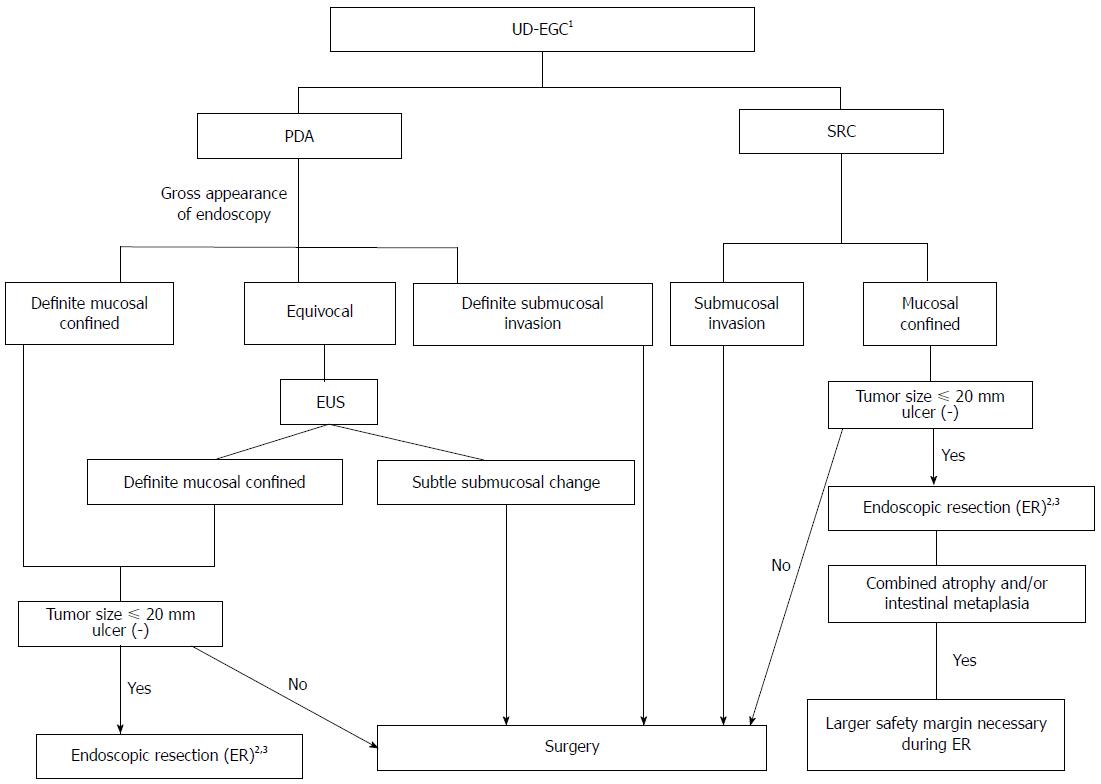

Figure 5 showed a suggested decision algorithm for ER of UD-EGC.

Figure 5 Suggested decision algorithm for endoscopic resection of undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer.

1Biopsy of several peripheral regions may aid in the exact diagnosis of undifferentiated-type histology prior to ER; 2Histologically minimum lateral margins should be wider than 3 mm for curative resection after ER; 3Even when complete resection has been achieved, short-term follow-up endoscopy to detect undifferentiated histology after ER may help to evaluate the risk of residual tumor development. PDA: Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma; SRC: Signet ring cell carcinoma; EUS: Endoscopic ultrasonography; ER: Endoscopic resection; UD-EGC: Undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer.

ADDITIVE TREATMENT AFTER NON-CR OF UD-EGC

The poorer CR rates of UD-EGC[6,10,29,30,32-34] than D-EGC suggest that additive treatments may be required after ER. Residual cancer cells and LNM were evident in surgical specimens of 50% and 13% of patients, respectively, when additive surgery was required because CR had failed[6,10,30,45]. Undifferentiated histology was the principal risk factor for residual tumor cells after histologically complete resection[44]. Thus, additional surgery may be appropriate after ER of UD-EGC. Hybrid natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery may be a good option for additional treatment after non-CR of UD-EGC. However, further work is necessary.

CONCLUSION

A low CR rate does not indicate that ER of UD-EGC should not be considered. The literature shows that patients who achieve CR after ER enjoy excellent survival outcomes. Furthermore the quality of life after stomach preservation is good. However, the biological behaviors of UD-EGC and D-EGC differ. Thus, decisions of ER in UD-EGC must be made very carefully, employing strict criteria based on the unique biological features of UD-EGC.

P- Reviewer: Novotny AR S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN