Published online Jul 28, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i28.6402

Peer-review started: March 27, 2016

First decision: May 12, 2016

Revised: May 26, 2016

Accepted: June 15, 2016

Article in press: June 15, 2016

Published online: July 28, 2016

Processing time: 117 Days and 14.7 Hours

The review focuses on those personality traits (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness), constructs (alexithymia and distressed - Type D personality) and emotional patterns (negative and positive) that are of particular concern in health psychology, with the aim to highlight their potential role on the pathogenesis, onset, symptom clusters, clinical course, and outcome of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Personality traits and emotional patterns play key roles in affecting autonomic, immune, inflammatory, and endocrine functions, thus contributing not only to IBS clinical expression and symptomatic burden, but also to disease physiopathology. In this sense, psychological treatments should address those personality traits and emotional features that are constitutive of, and integral to IBS. The biopsychosocial model of illness applied to IBS acknowledges the interaction between biological, psychological, environmental, and social factors in relation to pain and functional disability. A holistic approach to IBS should take into account the heterogeneous nature of the disorder, and differentiate treatments for different types of IBS, also considering the marked individual differences in prevalent personality traits and emotional patterns. Beyond medications, and lifestyle/dietary interventions, psychological and educational treatments may provide the optimal chance of addressing clinical symptoms, comorbid conditions, and quality of life in IBS patients.

Core tip: The complex nature of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) requires a multidisciplinary approach from different fields of scientific knowledge. This review examines the contribution of personality traits and emotional patterns to pathophysiology, clinical expression, and outcome of IBS. Several personality traits and constructs, such as neuroticism, conscientiousness, and alexithymia, are closely associated with IBS. Negative emotions, which are probably more entangled with neurobiological substrates, seem to have a key role in the brain-gut axis dysfunction which characterizes IBS. Based on the reviewed evidence, effective treatments for IBS should also address personality traits and emotions to improve outcomes in IBS patients.

- Citation: Muscatello MRA, Bruno A, Mento C, Pandolfo G, Zoccali RA. Personality traits and emotional patterns in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(28): 6402-6415

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i28/6402.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i28.6402

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional disorder of the lower gastrointestinal (GI) tract characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort, alterations in bowel habits (constipation and/or diarrhoea), and changes in stool frequency and/or form[1].

IBS has a great impact on socio-relational and work functioning, and patients usually report significant reduction of health-related quality of life, work productivity, and general distress in everyday life activities including diet, travel, physical appearance, family, education, and physical and sexual relationships[2]. In addition, IBS presents a primary healthcare burden accounting for the majority of the total health costs associated with general practitioners andgastroenterologists consultations, hospital admissions, and pharmacotherapy prescriptions.

The pathogenesis of IBS is heterogeneous and complex, probably resulting from interactions of several factors. Traditionally, pathophysiological explanations of IBS have focused on host-related factors such as abnormal motility, visceral hypersensitivity, and enhanced pain perception[3,4], although none of these factors can account for symptoms burden in the majority of IBS patients. Research has also focused on dietary intolerance[5], low grade inflammation and altered gut immune activation[6], intestinal permeability and alteration of microbiota[7], abnormalities in the autonomic nervous system[8], and stress[9].

More recently, the relationship among central nervous system (CNS), autonomic nervous system (ANS), and enteric nervous system (ENS), and the bi-directional communication between the neural and immunological networks within the gut, related to as the brain-gut axis, has provided a major contribution to the understanding of IBS pathogenesis[10]. The dysregulation and/or the hyperreactivity of the brain-gut axis involves neural, immune and endocrine pathways that are affected by environmental, biological and psychosocial stressors[11,12].

Basic and applied research across a range of clinical areas has established the importance of the biopsychosocial model of illness[13] that has provided a valid framework for understanding the bi-directional relationships between mind and body. Differently from prior paradigms which have offered purely biological or entirely psychosocial explanations, such perspective, integrating biological and clinical sciences with individual features, has postulated how heterogeneous factors and environmental processes interact together to affect physical health and illness onset, course, and outcome[14]. It has been suggested that psychosocial factors may modify the course of illness, and that their relative weight is quite variable, depending on individual differences, on illness typology, and also, in the same individual, that their contribution may even vary between different episodes of the same illness[13].

Actually, although the dominant model of disease still remains biomedical, a large amount of research have highlighted the role of psychological factors, stressful life events, and environmental demands in modulating individual vulnerability to diseases, whereas psychological well-being seems to be a protective factor in the dynamic interplay between health and illness[14]. Thus, taking into account general factors such as quality of life, daily functioning, productivity and social performances, cognitive abilities and emotional stability should be an essential part of diagnostic and clinical processes and patient care[15].

Within a holistic, person-centred perspective, there is a growing need to include patients related outcomes (PROs), such as self-reported symptoms, psychological well-being, patients’ satisfaction with treatments, and functional status in the context of clinical care and in treatment decision making, with the aim to provide subjective indicators of the impact of disease and of treatment efficacy, and a more extensive knowledge of clinical outcomes[16].

Within the biopsychosocial framework, IBS pathophysiology can be viewed as resulting from multiple interactions between biological mechanisms and psychosocial factors: external stressors, including life events, may affect and disrupt the regulation and activity of the brain-gut axis, therefore contributing to IBS onset, symptoms recrudescence, treatment response, and outcome[17]. Beyond psychosocial stressors, also genetic predisposition and early-life stress, both physiologic or psychological, may affect the bidirectional pathways between gut and brain, thus influencing individual vulnerability to develop IBS later in life, with each successive exposure to stressors possibly triggering or exacerbating IBS symptoms[18].

The role of negative effects, autonomic nervous system, stress-hormone and immune systems, along with psychiatric comorbidity and subclinical variations in depression, anxiety, and anger in relation to pathophysiology and clinical expression of IBS have been highlighted in our previous review on these issues[19].

The present review was aimed to examine the role of personality traits and prevalent emotional patterns on the pathogenesis, onset, symptom clusters, clinical course, and outcome of IBS within the biopsychosocial model of illness and disease.

The term personality refers to regularities and consistencies in behavior and forms of experience, including relatively consistent pattern of thoughts, feelings, and perceptions[20].

Although personality is actually an all-encompassing concept making other terms almost unnecessary, constructs as “temperament” and “character” are still used, and they offer a main contribute for a deep understanding of personality formation.

From a developmental perspective, individual differences appear early in life as simple, stylistic features of personality grounded on a biological substratum of relatively heritable differences in emotional reactivity and regulation, and in withdrawal/approach behaviors towards environmental stimuli; these early individual differences are encompassed under the term temperament[21]. Character refers to those aspects of personality that are shaped by learning and interaction with the environment; however, the distinction between temperament and character traits is not so clear cut, considering that each personality trait is virtually heritable, and its full expression will be ultimately determined by environmental influences, also mediated by epigenetic mechanisms altering genome function under exogenous stimuli[22].

One of the most interesting developments in personality research has been the emergence of the five-factor model accounting for the trait structure of personality[23]. The model identifies five broad personality dimensions that are assumed to have a biological origin, and that have demonstrated remarkable stability across cultures and, in the same individuals, for up to 45-year intervals[24].

The identified dimensions are neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Neuroticism refers to a tendency toward negative emotions (anxiety, hostility, depression) with high reactivity to physiological changes, emotional instability, vulnerability to stress, and an inclination toward impulsive behaviors. Extraversion refers to the attitude to experience positive emotions, warmth, excitement seeking, and activity. Openness to experience describes tendencies toward imagination and fantasy, aesthetics, creativity, ideas and values, and thought flexibility. Agreeableness involves a pro-social, altruistic orientation towards others, trust, straightforwardness, and tender-mindedness. Finally, Conscientiousness includes competence, order, self-discipline, and achievement striving.

There is a general agreement that the trait remains the best construct for conceptualizing individual differences; further consensus lies upon the hierarchical organization of traits, with a larger number of lower-ord er traits combined to form fewer higher-order traits. However, the nature of some of the putative traits is still a matter of debate within different frameworks; neuroticism and extraversion are clearly associated to the response to negative and positive emotions, respectively.

Thus, emotionality may be considered as a relatively stable individual trait, so that subjects characterized as highly emotional will strongly react to emotional stimuli, particularly negative ones.

Beyond the five-factor model, other personality constructs seem relevant in health research: alexithymia and the distressed (Type D) personality.

Alexithymia, one of the personality traits that has received higher attention in the psychosomatic literature, involves a reduced ability to identify, describe and discern subjective emotions and feelings, poor imaginative thought and introspection, and a cognitive style that is concrete and externally oriented[25].

Type D personality consists of two stable general traits: Negative affectivity, and social inhibition, and it is characterized by the tendency to experience negative emotions across a wide range of daily situations, and to suppress and inhibit emotional expression[26,27]. Table 1 highlights main personality models.

| Model | Features |

| Biosocial[21] | Temperament: heritable differences in emotional reactivity and regulation, and in withdrawal/approach behaviors towards environmental stimuli. |

| Character: aspects of personality that are shaped by learning and interaction with the environment. | |

| Five factor[23] | Neuroticism: tendency toward negative emotions (anxiety, hostility, depression) with high reactivity to physiological changes, emotional instability, vulnerability to stress, and an inclination toward impulsive behaviors. |

| Extraversion: attitude to experience positive emotions, warmth, excitement seeking, and activity. | |

| Openness to experience: tendencies toward imagination and fantasy, aesthetics, creativity, ideas and values, and thought flexibility. | |

| Agreeableness: pro-social, altruistic orientation towards others, trust, straightforwardness, and tender-mindedness. | |

| Conscientiousness: competence, order, self-discipline, and achievement striving. | |

| Alexithymia[25] | A reduced ability to identify, describe and discern subjective emotions and feelings, poor imaginative thought and introspection, and a cognitive style that is concrete and externally oriented. |

| Type D[26] | Negative affectivity: stable tendency to experience negative emotions (feelings of dysphoria and tension, negative view of self, somatic symptoms, attention bias towards adverse stimuli). |

| Social inhibition: stable tendency to inhibit the expression of emotions and behaviors in social interaction (feeling to be inhibited, tense and insecure when with others). |

The old-fashioned assumption which has dominated earliest psychosomatic research was that specific personality profiles were associated with specific somatic illnesses; however, no evidence has been reached by this line of research. More recently, a large amount of research has examined the relationships between personality traits and health, starting from the hypothesis that personality traits could be distal predictors of health outcomes, influencing health outcomes either directly[28] or via a number of mechanisms. Three main mechanisms have been identified: pathogenesis, in which traits may result in various physiological reactions both to external and internal stimuli, leading to susceptibility to illness, health behaviors, and coping with illness[29]. Furthermore, personality traits may also influence health via social cognitions and associative processes, whereby environments become associated with symptoms and illness behaviors, acting as triggers to illness presentation[30], and, finally, communication with health professionals. Regarding pathogenesis, consistent individual differences in stress reactivity as documented by changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, measured by cortisol levels, and in the ANS system, as indexed by cardiovascular activity, may reflect consistent variations in basic personality traits. It is almost convincing that variations in reactivity to stressors are to some extent built on individual differences in personality traits; beyond stress perception and biological reactions to stressors[31], personality traits have an acknowledged influence on stressful life event exposure, a process known as stress generation[32]. Higher neuroticism and impulsivity, along with lower agreeableness, directly predicted the occurrence of dependent stressful life events, those events which are partly attributable to the person’s own behavior, and indirect effects linked these personality traits to new health problems, suggesting that personality-related stress generation contributes to the decline of physical health in late mid-life[33].

More directly, neuroticism has been also associated with reduced cellular immune activity[34], increased pro-inflammatory cytokine levels[35], and lower cortisol stress reactivity[36]; a negative constellation of personality traits involving higher neuroticism, lower agreeableness and openness was associated with diminished stress reactions both of the cardiovascular system and the HPA axis[37]. The association between neuroticism and blunted physiological stress responses has not been extensively replicated, since a number of studies reported no association between neuroticism and cortisol changes during exposure to stressors[38,39].

Other personality traits of the five-factor model have received less attention in the context of health studies. Extraversion was related to reduced cytokine levels, increased cortisol levels, and, along with high levels of Openness and Conscientiousness, to slow disease progression[40]; moreover, low conscientiousness was associated with higher cumulative illness burden in later life[41], whereas high conscientiousness was a reliable predictor of longevity[42]. No relationships were found among agreeableness, cortisol levels, and cardiovascular stress reactivity, whereas conflicting results have been reported for openness[43,44].

Moving towards other personality constructs, it has been proposed that alexithymia could affect health through a number of pathways, directly influencing autonomic, immune and endocrine activities leading to tissue damage and to the increased vulnerability to illnesses, or indirectly, by somatosensory amplification that causes low tolerance to painful stimuli[45]. Alexithymic trait resulted associated with increased mortality[46], worse physical health outcomes[47], increased risk taking, internet addiction, and negative health and sexual behaviors[48-50]. High prevalence of alexithymia was found in major diseases, such as cancer[51], type 1 diabetes[52], and systemic lupus erythematosus[53].

Finally, Type D personality seems to confer a specific vulnerability to chronic stress, and it has been associated with increased pro-inflammatory cytokine levels[54], higher risk of morbidity, mortality, low subjective and physician-assessed health ratings, lesser health behaviors[41], and worse illness perceptions in cancer survivors[55].

Overall, findings from health research highlight the potential role of personality, conceived as built up from broad and stable traits, as a unifying structure embracing heterogeneous psychosocial factors which tend to cluster together, and contribute to raise the risk for illness onset, course, and outcome.

The large amount of findings reporting high rates of psychological symptoms and psychiatric comorbidity in IBS seems to indicate that affective and psychosocial symptoms may be specific and basic to the syndrome; nevertheless, research on personality structure and traits distribution in IBS subjects is still questionable.

Early studies on personality factors in IBS patients were performed by using the Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI)[56] which measures two pervasive, independent, and opposite dimensions of personality, the polarities extraversion-introversion and neuroticism-stability; these dimensions, according to the Authors, should account for most of the variance in the personality domain. Neuroticism scores on the EPI resulted significantly higher only in diarrhoea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) subjects when compared with patients affected by ulcerative colitis and general medical patients[57]. Palmer et al[58] evidenced that IBS patients were significantly more neurotic and less extroverted than general population (established normative data), but significantly less neurotic and more extroverted than patients affected by psychoneurotic disorders (neurotic depression, anxiety phobic state, obsessional illness, hysterical disorder, or a combination of these). However, it should be taken into account that the cited studies are characterized by small samples, low statistical power, restricted range, and arbitrary categorization of psychiatric disorders.

The shared agreement reached by the five-factor model[23] as a useful theoretical framework for understanding and describing basic personality dimensions, and the development of reliable questionnaires, such as the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI)[59] for the assessment of the factor structure of personality descriptors, have led to a renewed interest in exploring personality factors in functional GI disorders (FGIDs).

As reviewed in the previous section, among the five factors neuroticism has been identified as the personality dimension more closely associated to health and illness processes, and this evidence is also supported in IBS research[60]. Neuroticism, which confers a marked vulnerability to negative emotions, is one of the main features of patients with FGIDs also when controlling for psychiatric comorbidity[61], and it has also been identified as a risk factor for the development of IBS[62].

A community study evidenced an association between neuroticism and a past history of sexual, physical, and emotional/verbal abuse in IBS patients, suggesting that neuroticism could predispose to the reporting or development of IBS symptoms by a subset of subjects[63]. The link between neuroticism and abuse has been further supported by a more recent, longitudinal study by the same research group: abuse during childhood was significantly associated with elevated levels of neuroticism which was strongly related with baseline prevalence of depression and anxiety, and with moderately elevated scores on interference with life and activities, but not pain. Based on their findings, the Authors suggested a conceptual model for IBS characterized by a “vicious circle” between mood disorders and bowel symptoms in adulthood, with initial input from early life factors[64].

Regarding the evaluation of the five personality factors in prevalent IBS subtypes IBS-D, constipation-predominant (IBS-C), and alternating diarrhoea and constipation (IBS-A), two studies have reported conflicting results.

A first study in non-psychiatric IBS subjects showed that IBS-C patients were characterized by higher levels of neuroticism and conscientiousness, as documented by higher mean scores on the NEO-FFI[65]. Opposed findings have been reported by a cross-sectional study on a sample of Japanese university students, since IBS-D patients showed higher levels of neuroticism than IBS-C subjects and healthy controls; moreover, neuroticism was positively correlated with the severity of IBS symptoms[66]. Such conflicting results reflect the heterogeneity of findings from research assessing negative emotions and psychological distress in IBS subtypes, with studies reporting more psychological symptoms in IBS-C patients[67,68], and others documenting higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity and psychological distress in IBS-D patients[69]. It is well-known that negative emotionality, a feature of neuroticism, can increase colonic motility, and this effect is more evident in IBS patients[70]; high levels of neuroticism, anxiety sensitivity, trait worry, and increased vigilance toward visceral sensations are common features of IBS patients and reliable predictors of IBS symptoms[71]. However, it seems quite difficult to interpret these findings, and it remains unclear to draw univocal conclusions from research on personality and psychological differences among IBS subtypes, as documented by the mixed results reported in a recent meta-analysis[72].

Beyond neuroticism, another personality dimension, conscientiousness, resulted sporadically related with IBS in previous studies[65]. More recently, complaint severity in IBS patients was found negatively associated with conscientiousness and agreeableness, and positively associated with neuroticism and anxiety; the relationship between complaint severity reports and conscientiousness was modified by genetic variation in catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) which is involved in mediating sympathetic and dopaminergic tone through catecholamines degradation, thus participating in the complex affective, personality, and cognitive networks also involved in IBS pathophysiology and clinical expression[73].

A quite consistent amount of research has examined the role of alexithymia in IBS. Alexithymia has been found significantly associated with IBS and others FGIDs with variable prevalence rates (up to 66%), probably depending on methodological differences in diagnostic and assessment criteria[74,75]; moreover, alexithymia seems to affect responsiveness to treatment[75,76].

A study aimed at evaluating potential psychosocial predictors of IBS diagnosis and severity has identified six factors that significantly predicted IBS symptom severity, accounting for 61.3% of the variance: two alexithymia features (difficulty in identifying feelings and in describing feelings), gender, maladaptive cognitive schemas (defectiveness/shame and entitlement), and general psychological distress[77]. Similar findings emerged from a recent study that assessed alexithymic features and gastrointestinal-specific anxiety (GSA), which refers to worry, hypervigilance to, fear, and avoidance of GI sensations and contexts in IBS patients; results showed the association among alexithymia, GSA, and severity of IBS symptoms, with alexithymia explaining much more unique variance in IBS severity as compared with GSA[78]. Potential mechanisms by which alexithymia could affect IBS severity include the core features of this personality construct, such as the tendency to focus on, intensify, and misinterpret bodily sensations and somatic sensations triggered by states of emotional arousal; moreover, higher pain intensity to rectal distension in alexithymic IBS patients than in non-alexithymic controls has been documented[79].

Type D personality, the latest personality construct taken into account for the purposes of the present review, has not received the same attention as other personality factors in IBS research.

One study[80] evidenced that Type D personality, whose prevalence reached 40.6% in the examined sample, significantly decreased health-related quality of life (HRQoL); this finding was congruent with the extensive evidence of impaired HRQoL in several clinical samples affected by diseases other than GI disorders, mainly in coronary heart disease patients[54]. However, regression analyses showed that only the dimension negative affect of Type D personality, along with severity of symptoms and duration of treatment, remained strong independent determinant of HRQoL, whereas no significant associations between social inhibition and HRQoL were found.

Yet, caution is needed in interpreting such findings, since the established association between Type D personality and quality of life exclusively relies on negative affectivity which could affect HRQoL independently from the personality construct. A further study reported significantly higher prevalence rates of Type D personality in IBS patients than in healthy controls (45.4% vs 12.8%, respectively); Type D personality was significantly correlated with poor self-reported sleep quality, and it remained an independent predictor of impaired sleep also when controlling for the confounding influence of socio-demographic and clinical variables, including anxiety, and depression symptoms[81].

Taken together, the available findings do not allow drawing firm conclusions on the contribution of personality traits and constructs to IBS pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and severity of symptoms. This may be due to the complex nature of personality dimensions that are formed by higher order-traits comprising simpler, basic dimensions, such as emotional features, which are probably more connected to neurobiological substrates. Table 2 summarizes the association between personality and IBS.

| -Several personality traits and constructs, such as neuroticism, conscientiousness, and alexithymia, are closely associated with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). |

| -Negative emotionality, a feature of neuroticism, can increase colonic motility; high levels of neuroticism, anxiety sensitivity, trait worry, and increased vigilance toward visceral sensations are common features of IBS patients and reliable predictors of IBS symptoms. |

| -The relationship between complaint severity reports and conscientiousness was modified by genetic variation in catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) which is involved in mediating sympathetic and dopaminergic tone through catecholamines degradation, thus participating in the complex affective, personality, and cognitive networks also involved in IBS pathophysiology and clinical expression. |

| -Potential mechanisms by which alexithymia could affect IBS severity include the core features of this personality construct, such as the tendency to focus on, intensify, and misinterpret bodily sensations and somatic sensations triggered by states of emotional arousal; moreover, higher pain intensity to rectal distension in alexithymic IBS patients than in non-alexithymic controls has been documented. |

In the following sections we review main emotional patterns and their possible implications in health and IBS.

Emotional patterns may be conceived as individual differences in emotional reactivity, processing and regulation; more specifically, they involve detection and appraisal of emotionally salient stimuli, and regulatory processes that can be automatic or controlled, conscious or unconscious, occurring at one or more points in the emotion generative process and final expression.

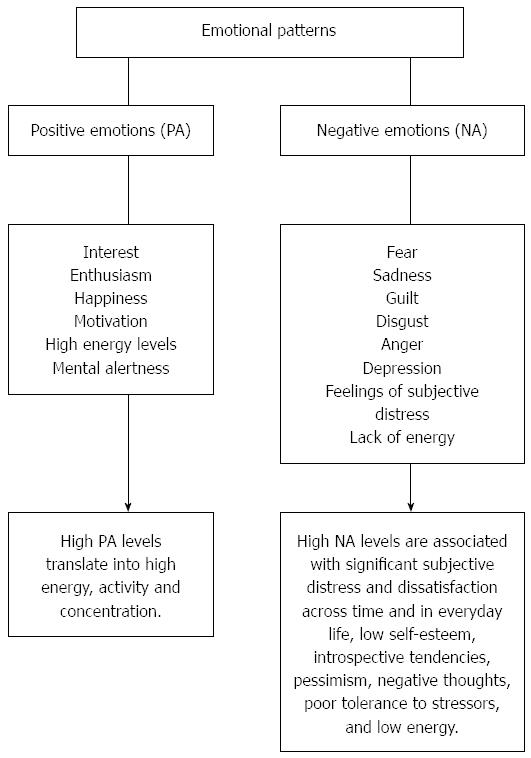

Two broad dimensions of emotional patterns, accounting for the most part of basic individual differences in affective processes and emotional responses, and involved in psychological well being and distress, have been identified: positive affect (PA), or pleasantness, and negative affect (NA), or unpleasantness[82] (Figure 1). Although PA and NA, for their seemingly opposite nature, could be considered as two basic, separate poles of the same affective continuum, they are rather discrete dimensions describing not only positive vs negative valence (e.g., happy vs sad), but also involving activation levels (e.g., aroused vs unaroused)[83]. This approach is particularly functional to health research for connecting affective activation with physiological arousal, which is thought to be a primary pathway through which emotions may influence health[84].

PA is a dimension reflecting pleasurable engagement with the environment, and characterized by the prevalence of positive feelings and mood states such as interest, enthusiasm, happiness, motivation, high energy levels, mental alertness[85]; high PA levels translate into high energy, activity and concentration, whereas low PA is a state of fatigue and poor energy.

NA is a pervasive disposition to experience aversive emotions, such as fear, sadness, guilt, disgust, anger, depression, feelings of subjective distress, and lack of energy; high NA levels are associated with significant subjective distress and dissatisfaction across time and in everyday life, low self-esteem, introspective tendencies, pessimism, negative thoughts, poor tolerance to stressors, and low energy[86].

In an evolutionary sense, quite discordantly from the assumptions of folk psychology that postulate that negative emotions are worse than positive ones, negative emotions are evolved adaptations which served the purpose of surviving in life-threatening situations, and their adaptive value lies in their ability to elicit specific action tendencies[87,88]. Anger and fear, for instance, evoke the “fight or flight” response, the urges to attack, also in defensive terms, or to escape, mobilizing optimal physiological support for the action called forth, and requiring substantial physical energy also through heightened cardiovascular reactivity that redistributes blood flow to relevant motor districts, and through specific neuroendocrine pathways that sustain the stress reactions[89].

On the other hand, positive emotions evoke nonspecific action tendencies (e.g., approach behaviors) and, secondarily, they are characterized by a relative lack of autonomic reactivity[89].

It has also been suggested that, whereas most negative emotions narrow individuals’ thought-action repertoires, according to the purpose of generating specific and targeted action tendencies, many positive emotions broaden individuals’ behavioral repertoires, prompting them to pursue a broader range of actions such as explore, play, approach, and building vital physical, cognitive, and social resources[90]. Furthermore, positive emotions lead to more prosocial and affiliative behaviors, and facilitate cognitive flexibility by shifting selective attention to reward stimuli in the environment[91].

PA and NA can be brief and transient, longer lasting, or trait-like features; within the research area on the impact of emotions on general health, each of these possibilities has been taken into account[92]; for the purposes of this review, in the next section we summarize research that has evaluated stable emotional patterns as trait attributes of individuals.

A growing evidence indicates that emotional states are associated with health. Whether the chronic experience of negative emotions can influence the development of illness, or trigger and exacerbate disease episodes, is still a matter of debate. Furthermore, it must also be taken into account that the effects of emotions in a healthy biological system may be rather different from effects in an impaired organism[93]. When exploring the possible influence of emotions on health, both the nature of the emotional experience, including valence (positive vs negative), frequency, intensity, and duration, and the type of the disease and course features, such as stage, progression, and severity, must be considered.

From a longitudinal point of view, and within a developmental framework, it has been shown that patterns of emotional functioning that emerge in childhood are almost maintained into adulthood; thus, emotional functioning in childhood may provide an early indicator of adult health risk[94]. High chronic distress in childhood has been associated with a range of adult physical health outcomes such as number of physical illnesses[95], inflammatory diseases[96], and obesity[97].

Positive emotions are generally associated with improved physical and mental health[98], reduced risk of stroke[99], and lower mortality in both older groups and chronically ill samples[100].

However, it has also been shown that high levels of PA may be detrimental to end-stage or high short-term mortality diseases, whereas diseases with longer term expectations for living, in which adherence to medical regimens and diverse behavioral factors (e.g., healthy lifestyles) could play a role, were benefited or unaffected by PA[92].

Most research have focused on the harmful impact of NA on health: to the extent that negative emotions generate cardiovascular reactivity, higher NA has been mainly related to heart disease[101]; further lines of research have examined NA role in cancer[102], and in chronic illnesses, such as arthritis and diabetes[93].

Two sets of candidate mechanisms by which emotions may influence physical health have been highlighted. The first approach involves the impact of emotional states on thoughts and conducts that may potentially influence health-related behaviors, such as perceptions of risks, decisions to seek medical screenings or treatment, adherence to exercise and dietary regimens[103], strength and quality of social support, and interpersonal relationships driven by the predominant emotional pattern[104]. In a broad sense, positive affectivity and well-being are associated with healthy habits and lifestyles, as documented by the inverse relationships among depression, anxiety, and leisure-time physical activity[105]. On the other hand, negative effects are related to unhealthy patterns of functioning, poorer social networks, higher frequency of stressful events, and negative social interactions[92].

A more intriguing hypothesis that has received support by a growing body of research[106,107] suggests that emotions have the potential to directly influence health through psychobiological processes, defined as the physiological consequences associated with emotional arousal and subsequent changes in multiple systems (e.g., cardiac functioning, blood pressure, inflammation and immune responses, neuroendocrine pathways), thus leading to increased vulnerability to illness, or modifying illness course and progression[108]. It is acknowledged that negative emotions confer increased risk for disorders with an inflammatory and immune aetiology[109]: depression, anxiety, and anger have been linked with higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin IL-6 and other inflammation mediators, including C-reactive protein, and cellular adhesion molecules[110-112].

Research that has examined negative emotions in relation to the main pathophysiological and symptomatic correlates of IBS has most commonly considered anger, anxiety, and depression[67,113,114].

Such discrete emotions have been consistently associated to visceral and pain hypersensitivity. In the presence of negative emotions, visceral sensations tend to be more noticeable and labeled as painful[115]. IBS patients, but also subjects with mild GI symptoms, presented attentional biases to GI pain-related symptoms and social threats words[116], a higher tendency to scan the body for symptoms, and a greater burden of abdominal pain[117] than healthy controls.

Also in IBS children and their parents negative emotions and multiple somatic complaints have been consistently reported[118]; furthermore, up to 45% of children with functional abdominal pain (FAP) displayed clinically elevated anxiety[119], whereas adolescents with frequent abdominal pain resulted at increased risk for depression, social isolation, and impairment in school functioning[120]. A study on a small sample of IBS children (n = 10; mean age 10.5 ± 2.2 years) has demonstrated a significant correlation between emotional instability and indexes of visceral hypersensitivity; emotional instability involved negative emotions, impulsiveness and impatience, all features associated with less effective ability to manage stressful life events[121].

In adults, evidence is more controversial: depression and anxiety were positively related with abdominal pain and pain duration[117], anxiety, depression, and the recall of painful memories were associated with a greater perception of visceral pain[122], depression levels were higher in those patients who reported lowered rectal pain threshold, but only in the alternating IBS subtype[123], whereas other studies did not find significant differences in negative emotions and pain thresholds according to IBS subtypes[124].

Regarding intestinal motility patterns, emotional arousal can augment colonic motility and diarrhoea also in healthy subjects, but this effect is mostly pronounced in IBS patients[70]; laboratory studies have provided evidence that anger-provoking conditions significantly increased colon motility in IBS patients, whereas anger suppression was associated with prolonged gastric emptying and delayed gut transit[125-127].

A role for negative emotions in low-grade inflammation and altered immune activity in IBS has garnered support from studies demonstrating alterations on several inflammatory and immune parameters resulting in an imbalance of the proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines: elevated peripheral levels of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukine (IL)-1β and tumor necrosis factor α, and decreased levels of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, differentiated IBS patients with anxiety and depression from IBS subjects without negative emotions, and from healthy controls[128,129].

Finally, negative emotional patterns seem to be involved in another clinical feature of IBS: health-care seeking behavior. Anxiety has been identified as one of the main reason of medical consultation among IBS subjects[130]. However, the opposite is also true; the co-occurring experience of life events eliciting emotional arousal can lead individuals to attribute IBS symptoms to the stressful situation[112]. A recent study on a community sample of university students with IBS-like symptoms compared with a non-IBS reference group showed that health care utilization was mainly associated with IBS symptom severity, and not with emotional distress[131]. On the other hand, health care-seeking behavior is a non-specific feature of IBS patients, and it depends on many factors, such as the presence of pain, the severity of bowel symptoms, and duration of illness.

Overall, in interpreting findings from studies of negative emotions and IBS it seems important to bear in mind the utility of a dimensional method based on the assumption that emotions rarely occur in isolation; thus, considering emotional patterns rather than each emotion in isolation could lead to a more realistic approach to the pathophysiology and clinical expression of IBS.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis has suggested that neither psychological markers nor symptom-based criteria and/or biomarkers alone performed well in diagnosing IBS, whereas combining symptoms, biomarkers and/or psychological markers seemed to perform better. The Authors suggested that one possible reason for the poor performance of psychological markers was that the reviewed studies predominantly used markers of anxiety and depression to predict the presence of IBS, whereas it would be more useful to include other emotional dimensions beyond anxiety and depression for improving the accuracy of diagnosing IBS[132]. Table 3 shows main findings on emotional patterns and IBS.

| -Negative emotions, which are probably more entangled with neurobiological substrates, seem to have a key role in the brain-gut axis dysfunction which characterizes irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). |

| -Anger, anxiety, and depression have been consistently associated to visceral and pain hypersensitivity. In the presence of negative emotions, visceral sensations tend to be more noticeable and labeled as painful. |

| -Emotional arousal can augment colonic motility and diarrhoea; laboratory studies have provided evidence that anger-provoking conditions significantly increased colon motility in IBS patients, whereas anger suppression was associated with prolonged gastric emptying and delayed gut transit. |

| -A role for negative emotions in low-grade inflammation and altered immune activity in IBS has garnered support from studies demonstrating alterations on several inflammatory and immune parameters resulting in an imbalance of the proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines. |

The biopsychosocial model applied to IBS acknowledges and highlights the interaction between biological, psychological, environmental, and social factors in relation to pain and functional disability. Within this framework, and also considering the bidirectional communications within the brain-gut axis, a holistic approach involving medications, lifestyle changes, dietary interventions, psychopharmacological and psychological treatments, and educational and behavioral strategies should provide the optimal chance of addressing clinical symptoms, comorbid conditions, and quality of life in IBS patients.

Psychological and psychosocial treatments involving interactions between body and mind could be effective treatment strategies in reducing GI symptoms in adults with IBS; psychological interventions were significantly effective at first post-treatment assessment and at both short-term and long-term follow-up[133].

Various models of psychotherapy have been used in IBS with promising results; cognitive behavioral therapy, gut-directed hypnotherapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, mindfulness, body awareness psychotherapy, relaxation/stress management, and meditation have been proven effective on gastrointestinal symptoms and quality of life in IBS patients[134,135].

As reviewed in the previous sections, personality traits and emotional patterns play key roles in affecting autonomic, immune, inflammatory, and endocrine functions, thus contributing not only to IBS clinical expression and symptomatic burden, but also to disease physiopathology. In this sense, psychological treatments should address those personality and emotional features that are constitutive of and integral to IBS.

The choice of a specific psychological model should take into account individual differences in clinical symptoms and personality features, after a careful assessment including a broad evaluation of gastrointestinal and pain symptoms, hyperarousal, emotional patterns, personality traits and profile, psychosocial aspects, and quality of life.

It has been shown that cognitively-focused therapies, such as comprehensive self-management, were less effective in reducing clinical and pain symptoms in IBS patients with higher sympathetic tone[136]. IBS patients characterized by high levels of negative emotions could benefit of treatments aimed at activating inhibitory processes through the utilization of emotion regulation techniques to down-regulate emotional arousal, and to enhance self-regulation of affective reactions to internal and environmental stimuli[137,138]. Beyond negative emotions, the trait of neuroticism is characterized by dysfunctional cognitions, worries, negative appraisals and catastrophizing, defined as the attitude to put emphasis on the threat value of painful stimuli[139]; accordingly, IBS patients with accentuated neuroticism as the prevalent personality trait could ameliorate on cognitive treatments targeting dysfunctional beliefs, automatic thought processes, and cognitive biases.

Impaired body awareness has been reported in IBS-D patients[69] and in alexithymia[140]; particularly when an alexithymic component is present, body awareness techniques and psychoeducational strategies oriented to reduce misinterpretation of bodily sensations could be useful for helping patients to identify and express emotions, and to disentangle somatic symptoms from signs of emotional arousal[141].

Based on the reviewed evidence, multi-symptomatic IBS patients requires a complex, multidisciplinary approach. The process of prescribing pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments should take into account the heterogeneous nature and clinical presentation of the disorder, attempting to differentiate the treatment for different types of IBS, also considering the profound individual differences in prevalent personality traits and emotional patterns.

A large amount of research has provided evidence that personality traits and emotional patterns influence health, disease, and quality of life through a range of biological and behavioral pathways, including physiological reactions to stimuli, reactivity to stressors, health behaviors, and coping with illness. This evidence also extends to IBS: personality and affective features are central components of the biopsychosocial model of IBS, being involved in functioning and dysregulation of the brain-gut axis, and contributing to the onset, recurrence and recrudescence of IBS. From early developmental stages, both genetic and environmental factors interact to shape emotional arousal and regulation, vulnerability to stressors, effective or maladaptive coping strategies, visceral and pain sensitivity, and thus symptom perception, illness behavior, daily functioning, quality of life and, finally, health outcomes.

Given the relationships above, it is increasingly evident that a complex and heterogeneous disease such as IBS requires a multidisciplinary, integrated approach coming from different, although complementary disciplines. Further insights on vulnerability factors and pathophysiological pathways leading to symptoms clusters and clinical expression of IBS should be addressed in order to promote better health, quality of life, and effective treatments for IBS patients.

Manuscript Source: Invited manuscript

Specialty Type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country of Origin: Italy

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Farhadi A, March El-Salhy M S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Chey WD, Kurlander J, Eswaran S. Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. JAMA. 2015;313:949-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 629] [Cited by in RCA: 741] [Article Influence: 74.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Spiegel BM. The burden of IBS: looking at metrics. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009;11:265-269. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Mayer EA, Aziz Q, Coen S, Kern M, Labus JS, Lane R, Kuo B, Naliboff B, Tracey I. Brain imaging approaches to the study of functional GI disorders: a Rome working team report. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:579-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Elsenbruch S. Abdominal pain in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: a review of putative psychological, neural and neuro-immune mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:386-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Atkinson W, Sheldon TA, Shaath N, Whorwell PJ. Food elimination based on IgG antibodies in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2004;53:1459-1464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 347] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Philpott H, Gibson P, Thien F. Irritable bowel syndrome - An inflammatory disease involving mast cells. Asia Pac Allergy. 2011;1:36-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ringel Y, Ringel-Kulka T. The Intestinal Microbiota and Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49 Suppl 1:S56-S59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Berman S, Suyenobu B, Naliboff BD, Bueller J, Stains J, Wong H, Mandelkern M, Fitzgerald L, Ohning G, Gupta A. Evidence for alterations in central noradrenergic signaling in irritable bowel syndrome. Neuroimage. 2012;63:1854-1863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Moloney RD, Johnson AC, O’Mahony SM, Dinan TG, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, Cryan JF. Stress and the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Visceral Pain: Relevance to Irritable Bowel Syndrome. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016;22:102-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fichna J, Storr MA. Brain-Gut Interactions in IBS. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mayer EA, Tillisch K. The brain-gut axis in abdominal pain syndromes. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:381-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tanaka Y, Kanazawa M, Fukudo S, Drossman DA. Biopsychosocial model of irritable bowel syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:131-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Engel GL. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137:535-544. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Cameron DS, Bertenshaw EJ, Sheeran P. The impact of positive affect on health cognitions and behaviours: a meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9:345-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fava GA, Sonino N. The clinical domains of psychosomatic medicine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:849-858. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Acquadro C, Berzon R, Dubois D, Leidy NK, Marquis P, Revicki D, Rothman M; PRO Harmonization Group. Incorporating the patient’s perspective into drug development and communication: an ad hoc task force report of the Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Harmonization Group meeting at the Food and Drug Administration, February 16, 2001. Value Health. 2003;6:522-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 355] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | McComb H. Primary repair of the bilateral cleft lip nose: a 15-year review and a new treatment plan. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:882-899; discussion 889-890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ben-Israel Y, Shadach E, Levy S, Sperber A, Aizenberg D, Niv Y, Dickman R. Possible Involvement of Avoidant Attachment Style in the Relations Between Adult IBS and Reported Separation Anxiety in Childhood. Stress Health. 2015; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Muscatello MR, Bruno A, Scimeca G, Pandolfo G, Zoccali RA. Role of negative affects in pathophysiology and clinical expression of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7570-7586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bromley DB. Personality description in ordinary language. London: Wiley 1977; . |

| 21. | Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Evans DE. Temperament and personality: origins and outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78:122-135. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Probst AV, Dunleavy E, Almouzni G. Epigenetic inheritance during the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:192-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 567] [Cited by in RCA: 580] [Article Influence: 36.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Costa PT, McCrae RR. Stability and change in personality assessment: the revised NEO Personality Inventory in the year 2000. J Pers Assess. 1997;68:86-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Terracciano A, Costa PT, McCrae RR. Personality plasticity after age 30. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2006;32:999-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JDA. Disorders of affect regulation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1997; . |

| 26. | Denollet J. Type D personality. A potential risk factor refined. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49:255-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Denollet J. DS14: standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition, and Type D personality. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:89-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 969] [Cited by in RCA: 955] [Article Influence: 47.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chapman BP, Weiss A, Fiscella K, Muennig P, Kawachi I, Duberstein P. Mortality Risk Prediction: Can Comorbidity Indices Be Improved With Psychosocial Data? Med Care. 2015;53:909-915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Roberts BW, Kuncel NR, Shiner R, Caspi A, Goldberg LR. The Power of Personality: The Comparative Validity of Personality Traits, Socioeconomic Status, and Cognitive Ability for Predicting Important Life Outcomes. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2007;2:313-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1360] [Cited by in RCA: 916] [Article Influence: 50.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Conner M, Abraham C. Conscientiousness and the theory of planned behavior: Toward a more complete model of the antecedents of intentions and behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2001;27:1547-1561. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Carver CS, Connor-Smith J. Personality and coping. Annu Rev Psychol. 2010;61:679-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1109] [Cited by in RCA: 989] [Article Influence: 65.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Liu RT, Alloy LB. Stress generation in depression: A systematic review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future study. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:582-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 502] [Cited by in RCA: 444] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Iacovino JM, Bogdan R, Oltmanns TF. Personality Predicts Health Declines Through Stressful Life Events During Late Mid-Life. J Pers. 2015; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Herbert TB, Cohen S. Stress and immunity in humans: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 1993;55:364-379. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, Lanctôt KL. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:446-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3039] [Cited by in RCA: 3402] [Article Influence: 226.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Chida Y, Hamer M. Chronic psychosocial factors and acute physiological responses to laboratory-induced stress in healthy populations: a quantitative review of 30 years of investigations. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:829-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 414] [Cited by in RCA: 414] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Bibbey A, Carroll D, Roseboom TJ, Phillips AC, de Rooij SR. Personality and physiological reactions to acute psychological stress. Int J Psychophysiol. 2013;90:28-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Verschoor E, Markus CR. Effects of acute psychosocial stress exposure on endocrine and affective reactivity in college students differing in the 5-HTTLPR genotype and trait neuroticism. Stress. 2011;14:407-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Hutchinson JG, Ruiz JM. Neuroticism and cardiovascular response in women: evidence of effects on blood pressure recovery. J Pers. 2011;79:277-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ironson GH, O’Cleirigh C, Weiss A, Schneiderman N, Costa PT. Personality and HIV disease progression: role of NEO-PI-R openness, extraversion, and profiles of engagement. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:245-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 41. | Chapman BP, Lyness JM, Duberstein P. Personality and medical illness burden among older adults in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:277-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kern ML, Friedman HS. Do conscientious individuals live longer? A quantitative review. Health Psychol. 2008;27:505-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Oswald LM, Zandi P, Nestadt G, Potash JB, Kalaydjian AE, Wand GS. Relationship between cortisol responses to stress and personality. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1583-1591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Williams PG, Rau HK, Cribbet MR, Gunn HE. Openness to experience and stress regulation. J Res Pers. 2009;43:777-784. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Lumley MA, Neely LC, Burger AJ. The assessment of alexithymia in medical settings: implications for understanding and treating health problems. J Pers Assess. 2007;89:230-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 349] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Tolmunen T, Lehto SM, Heliste M, Kurl S, Kauhanen J. Alexithymia is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in middle-aged Finnish men. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:187-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Grabe HJ, Schwahn C, Barnow S, Spitzer C, John U, Freyberger HJ, Schminke U, Felix S, Völzke H. Alexithymia, hypertension, and subclinical atherosclerosis in the general population. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:139-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Aïte A, Barrault S, Cassotti M, Borst G, Bonnaire C, Houdé O, Varescon I, Moutier S. The impact of alexithymia on pathological gamblers’ decision making: a preliminary study of gamblers recruited in “sportsbook” casinos. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2014;27:59-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Scimeca G, Bruno A, Cava L, Pandolfo G, Muscatello MR, Zoccali R. The relationship between alexithymia, anxiety, depression, and internet addiction severity in a sample of Italian high school students. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:504376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Scimeca G, Bruno A, Pandolfo G, Micò U, Romeo VM, Abenavoli E, Schimmenti A, Zoccali R, Muscatello MR. Alexithymia, negative emotions, and sexual behavior in heterosexual university students from Italy. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42:117-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | De Vries AM, Forni V, Voellinger R, Stiefel F. Alexithymia in cancer patients: review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom. 2012;81:79-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Chatzi L, Bitsios P, Solidaki E, Christou I, Kyrlaki E, Sfakianaki M, Kogevinas M, Kefalogiannis N, Pappas A. Type 1 diabetes is associated with alexithymia in nondepressed, non-mentally ill diabetic patients: a case-control study. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:307-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Barbasio C, Vagelli R, Marengo D, Querci F, Settanni M, Tani C, Mosca M, Granieri A. Illness perception in systemic lupus erythematosus patients: The roles of alexithymia and depression. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;63:88-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Denollet J, Conraads VM, Brutsaert DL, De Clerck LS, Stevens WJ, Vrints CJ. Cytokines and immune activation in systolic heart failure: the role of Type D personality. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17:304-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Mols F, Oerlemans S, Denollet J, Roukema JA, van de Poll-Franse LV. Type D personality is associated with increased comorbidity burden and health care utilization among 3080 cancer survivors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34:352-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual for the Eysenck Personality Inventory. San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service 1968; . |

| 57. | Esler MD, Goulston KJ. Levels of anxiety in colonic disorders. N Engl J Med. 1973;288:16-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Palmer RL, Stonehill E, Crisp AH, Waller SL, Misiewicz JJ. Psychological characteristics of patients with the irritable bowel syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1974;50:416-419. [PubMed] |

| 59. | Costa PT, McCrae RR. The NEO Personality Inventory manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment 1985; . |

| 60. | Bennett EJ, Tennant CC, Piesse C, Badcock CA, Kellow JE. Level of chronic life stress predicts clinical outcome in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1998;43:256-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Tanum L, Malt UF. Personality and physical symptoms in nonpsychiatric patients with functional gastrointestinal disorder. J Psychosom Res. 2001;50:139-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Labus JS, Mayer EA, Chang L, Bolus R, Naliboff BD. The central role of gastrointestinal-specific anxiety in irritable bowel syndrome: further validation of the visceral sensitivity index. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:89-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Talley NJ, Boyce PM, Jones M. Is the association between irritable bowel syndrome and abuse explained by neuroticism? A population based study. Gut. 1998;42:47-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Jones MP, Oudenhove LV, Koloski N, Tack J, Talley NJ. Early life factors initiate a ‘vicious circle’ of affective and gastrointestinal symptoms: A longitudinal study. United European Gastroenterol J. 2013;1:394-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Farnam A, Somi MH, Sarami F, Farhang S, Yasrebinia S. Personality factors and profiles in variants of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:6414-6418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Tayama J, Nakaya N, Hamaguchi T, Tomiie T, Shinozaki M, Saigo T, Shirabe S, Fukudo S. Effects of personality traits on the manifestations of irritable bowel syndrome. Biopsychosoc Med. 2012;6:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Muscatello MR, Bruno A, Pandolfo G, Micò U, Stilo S, Scaffidi M, Consolo P, Tortora A, Pallio S, Giacobbe G. Depression, anxiety and anger in subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome patients. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17:64-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Eriksson EM, Andrén KI, Eriksson HT, Kurlberg GK. Irritable bowel syndrome subtypes differ in body awareness, psychological symptoms and biochemical stress markers. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4889-4896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Guthrie E, Creed F, Fernandes L, Ratcliffe J, Van Der Jagt J, Martin J, Howlett S, Read N, Barlow J, Thompson D. Cluster analysis of symptoms and health seeking behaviour differentiates subgroups of patients with severe irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2003;52:1616-1622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, Temple RD, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE, Janssens J, Funch-Jensen P, Corazziari E. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569-1580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1502] [Cited by in RCA: 1427] [Article Influence: 44.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 71. | Hazlett-Stevens H, Craske MG, Mayer EA, Chang L, Naliboff BD. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome among university students: the roles of worry, neuroticism, anxiety sensitivity and visceral anxiety. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:501-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Fond G, Loundou A, Hamdani N, Boukouaci W, Dargel A, Oliveira J, Roger M, Tamouza R, Leboyer M, Boyer L. Anxiety and depression comorbidities in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264:651-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 474] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Hall KT, Tolkin BR, Chinn GM, Kirsch I, Kelley JM, Lembo AJ, Kaptchuk TJ, Kokkotou E, Davis RB, Conboy LA. Conscientiousness is modified by genetic variation in catechol-O-methyltransferase to reduce symptom complaints in IBS patients. Brain Behav. 2015;5:39-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Portincasa P, Moschetta A, Baldassarre G, Altomare DF, Palasciano G. Pan-enteric dysmotility, impaired quality of life and alexithymia in a large group of patients meeting ROME II criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2293-2299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Porcelli P, Guidi J, Sirri L, Grandi S, Grassi L, Ottolini F, Pasquini P, Picardi A, Rafanelli C, Rigatelli M. Alexithymia in the medically ill. Analysis of 1190 patients in gastroenterology, cardiology, oncology and dermatology. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:521-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Endo Y, Shoji T, Fukudo S, Machida T, Machida T, Noda S, Hongo M. The features of adolescent irritable bowel syndrome in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26 Suppl 3:106-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Phillips K, Wright BJ, Kent S. Psychosocial predictors of irritable bowel syndrome diagnosis and symptom severity. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75:467-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Porcelli P, De Carne M, Leandro G. Alexithymia and gastrointestinal-specific anxiety in moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:1647-1653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Kano M, Hamaguchi T, Itoh M, Yanai K, Fukudo S. Correlation between alexithymia and hypersensitivity to visceral stimulation in human. Pain. 2007;132:252-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Sararoudi RB, Afshar H, Adibi P, Daghaghzadeh H, Fallah J, Abotalebian F. Type D personality and quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:985-992. [PubMed] |

| 81. | Yıldırım O, Alçelik A, Canan F, Aktaş G, Sit M, İşçi A, Yalçin A, Yılmaz EE. Impaired subjective sleep quality in irritable bowel syndrome patients with a Type D personality. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2013;11:135-138. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Watson D, Clark LA. Negative affectivity: the disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychol Bull. 1984;96:465-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2526] [Cited by in RCA: 2001] [Article Influence: 50.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Posner J, Russell JA, Peterson BS. The circumplex model of affect: an integrative approach to affective neuroscience, cognitive development, and psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 2005;17:715-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1643] [Cited by in RCA: 849] [Article Influence: 42.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Cohen S, Kessler RC, Underwood Gordon L. Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists. London: Oxford University Press 1997; . |

| 85. | Clark LA, Watson D, Leeka J. Diurnal variation in the positive affects. Motiv Emotion. 1989;13:205-234. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Suls J. Affect, stress and personality. In Forgas JP. Handbook of affect and social cognition. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum 2001; 392-409. |

| 87. | Frijda NH. The emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1986; . |

| 88. | Lazarus RS. Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press 1991; . |

| 89. | Levenson RW. Human emotion: A functional view. The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions. New York: Oxford University Press 1994; 123-126. |

| 90. | Ashby FG, Isen AM, Turken AU. A neuropsychological theory of positive affect and its influence on cognition. Psychol Rev. 1999;106:529-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1210] [Cited by in RCA: 945] [Article Influence: 36.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Tamir M, Robinson MD. The happy spotlight: positive mood and selective attention to rewarding information. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2007;33:1124-1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Pressman SD, Cohen S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychol Bull. 2005;131:925-971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1160] [Cited by in RCA: 1082] [Article Influence: 56.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Kiecolt-Glaser JK, McGuire L, Robles TF, Glaser R. Psychoneuroimmunology: psychological influences on immune function and health. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:537-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol Bull. 2002;128:330-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1576] [Cited by in RCA: 1331] [Article Influence: 57.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Kubzansky LD, Martin LT, Buka SL. Early manifestations of personality and adult health: a life course perspective. Health Psychol. 2009;28:364-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Appleton AA, Buka SL, McCormick MC, Koenen KC, Loucks EB, Gilman SE, Kubzansky LD. Emotional functioning at age 7 years is associated with C-reactive protein in middle adulthood. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:295-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Goodwin RD, Sourander A, Duarte CS, Niemelä S, Multimäki P, Nikolakaros G, Helenius H, Piha J, Kumpulainen K, Moilanen I. Do mental health problems in childhood predict chronic physical conditions among males in early adulthood? Evidence from a community-based prospective study. Psychol Med. 2009;39:301-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: does happiness lead to success? Psychol Bull. 2005;131:803-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3557] [Cited by in RCA: 2069] [Article Influence: 103.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Ostir GV, Markides KS, Peek MK, Goodwin JS. The association between emotional well-being and the incidence of stroke in older adults. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:210-215. [PubMed] |

| 100. | Moskowitz JT. Positive affect predicts lower risk of AIDS mortality. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:620-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |