Published online Jul 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i26.6089

Peer-review started: March 29, 2016

First decision: April 14, 2016

Revised: May 7, 2016

Accepted: May 21, 2016

Article in press: May 23, 2016

Published online: July 14, 2016

Processing time: 100 Days and 2.1 Hours

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is generally a self-limited vasculitis disease and has a good prognosis. We report a 4-year-old Thai boy who presented with palpable purpura, abdominal colicky pain, seizure, and eventually developed intestinal ischemia and perforation despite adequate treatment, including corticosteroid and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Imaging modalities, including ultrasonography and contrast-enhanced computed tomography, could not detect intestinal ischemia prior to perforation. In this patient, we also postulated that vasculitis-induced mucosal ischemia was a cause of the ulcer, leading to intestinal perforation, and high-dose corticosteroid could have been a contributing factor since the histopathology revealed depletion of lymphoid follicles. Intestinal perforation in HSP is rare, but life-threatening. Close monitoring and thorough clinical evaluation are essential to detect bowel ischemia before perforation, particularly in HSP patients who have hematochezia, persistent localized abdominal tenderness and guarding. In highly suspicious cases, exploratory laparotomy may be needed for the definite diagnosis and prevention of further complications.

Core tip: Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) with intestinal perforation during the course of corticosteroid treatment was a rare condition. We report a HSP patient with vasculitis-induced mucosal ischemia, eventually leading to ulcer and intestinal perforation. No imaging modality could detect bowel ischemia before perforation. Histopathology of resected bowel also suggested that high-dose corticosteroids might be a contributing factor to intestinal perforation in this patient. Early treatment by surgical resection of ischemic bowel can prevent intestinal perforation and peritonitis, which are life-threatening complications.

- Citation: Lerkvaleekul B, Treepongkaruna S, Saisawat P, Thanachatchairattana P, Angkathunyakul N, Ruangwattanapaisarn N, Vilaiyuk S. Henoch-Schönlein purpura from vasculitis to intestinal perforation: A case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(26): 6089-6094

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i26/6089.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i26.6089

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is the most common childhood vasculitis disorder and is characterized by palpable purpura, arthritis or arthralgia, abdominal colicky pain, and nephritis. It is multi-systemic small vessel vasculitis, 50%-80% of which typically involves the gastrointestinal tract (GI), causing diffuse colicky pain due to submucosal or subserosal hemorrhage and edema. This GI disease is generally benign and has a good response to corticosteroid therapy in most cases. However, severe complications such as intussusception, massive GI bleeding, and intestinal perforation can occur. HSP-associated intestinal perforation is a rare complication but it is life-threatening and mortalities have been reported[1]. We present here a pediatric patient with severe HSP who developed intestinal ischemia and perforation without intussusception despite early and adequate corticosteroid therapy.

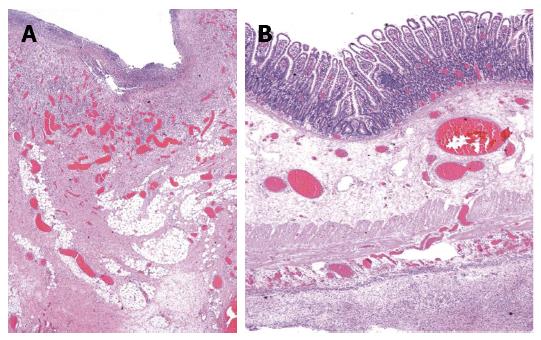

A 4-year-old Thai boy was referred to our hospital due to persistent severe abdominal pain and seizure. He had been hospitalized at a private hospital due to colicky abdominal pain and palpable purpura for two days prior to admission. On admission, the abdomen was soft on palpation and not tender. Furthermore, there was palpable purpuric rash on both legs. His CBC revealed hemoglobin 125 g/L, WBC 11.4 × 109/L, platelet 501 × 109/L. ESR was 14 mm/h. Kidney function was normal; BUN was 1.99 mmol/L, Creatinine was 23 μmol/L, and the urinary analysis showed specific gravity 1.020, no protein, no glucose, no blood, no bilirubin, WBC 0-1 cells/HPF, RBC 0-1 cells/HPF. The serum electrolyte showed sodium 132 mmol/L, potassium 4.2 mmol/L, chloride 94 mmol/L, bicarbonate 17.2 mmol/L, and the skin biopsy demonstrated small vessel vasculitis. Therefore, HSP was diagnosed and intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP) 2 mg/kg per day was started promptly. His abdominal pain had improved after the treatment, however two days later (D5) the pain recurred and was progressive. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed no intussusception. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed mild bowel wall edema at duodenum and proximal jejunum. On day six, he developed status epilepticus and alteration of consciousness. He was intubated and put on ventilator support. Antiepileptic drug treatment was started. While he was in an euvolemic state, his serum sodium was 120 mmol/L, urine osmolarity 100 mmol/kg, and serum osmolarity 256 mmol/kg. The etiology of seizure was thought to be hyponatremia due to syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone. MRI and MRA of the brain revealed no evidence of central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis. CSF fluid analysis was normal. Blood tests for anti-nuclear antibody, anti-double stranded DNA, and C3 were normal. Since CNS vasculitis could not be excluded, one dose of pulse methylprednisolone (MP) 30 mg/kg was commenced. Then he was referred to our hospital for further management. On the first day of presentation in our hospital (D7), his physical examination revealed drowsiness and no abdominal distension or guarding. CBC revealed thrombocytosis (553 × 109/L), WBC 10 × 109/L, and hemoglobin 110 g/L. ESR and CRP were 32 mm/h and 5 mg/L respectively. Urinalysis and serum creatinine level were normal. He subsequently regained consciousness and was extubated after serum sodium returned to normal level. The EEG was normal, therefore antiepileptic drug treatment was discontinued. The purpura faded away and the abdominal pain markedly improved, therefore IVMP was continued at the dose of 2 mg/kg per day. Abdominal pain recurred five days after admission to our hospital (D12) with tenderness and voluntary guarding at the right lower quadrant. Abdominal ultrasound revealed diffuse small bowel wall thickening and minimal ascites without intussusception. Corticosteroid resistant HSP was considered, and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) 2 g/kg was initiated. Two days later (D14), he developed hematochezia with tenderness and voluntary guarding at the right lower quadrant. Intestinal ischemia was suspected. A contrast-enhanced CT of the whole abdomen was performed and revealed a long segment of mild circumferential bowel wall thickening with preserved wall enhancement involving jejunum and ileum, but the evidence of bowel ischemia was inconclusive. He was also evaluated by pediatric surgeons and the continuation of medical treatment was suggested. Three days later (D17), he developed signs of peritonitis with abdominal distension, generalized guarding and tenderness. His body temperature was 38.3 °C, blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg, pulse rate was 130 beats/min, and respiratory rate was 26 breaths/min. Upright abdominal radiograph demonstrated intraperitoneal free air. An emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed and revealed ischemic ileum of 35 cm at 35 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve and large perforated ulcers, size 3.5 cm × 1.5 cm, on the ischemic bowel. The pathological examination macroscopically revealed a large perforated ulcer with fibrofibrinous exudates (Figure 1). The histopathology revealed mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with granulation tissue and fibrosis at the base of ulcer. The remaining bowel showed depletion of lymphoid follicles (Peyer’s patch), submucosal and subserosal congestion and diffuse peritonitis (Figure 2). After surgery, his general symptoms gradually improved and abdominal pain resolved. IVMP was switched to oral prednisolone, and then discontinued in week 3. The patient was discharged thirteen days after surgery (D31). He has been well without disease recurrence at the 4 mo follow-up. The summaries of clinical data, investigations, and treatment during the course of disease are shown in Table 1.

| Category | D1-3 | D5 | D6 | D7 | D12 | D14 | D17 | D31 |

| 8-10/1/15 | 12/1/15 | 13/1/15 | 14/1/15 | 19/1/15 | 21/1/15 | 24/1/15 | 7/2/15 | |

| Private hospital | This hospital | |||||||

| Symptoms | Intermittent abdominal pain, purpuric rash | Abdominal pain progressed | Seizure | Regained consciousness, abdominal pain improved, purpura faded away | Abdominal pain progressed | Persistent abdominal pain with hematochezia | Low grade fever, severe abdominal pain | No abdominal pain, normal appetite |

| Abdominal signs | Soft, mild tenderness | Generalized voluntary guarding | Soft, not tender | Localized guarding and tenderness at RLQ | Localized guarding and tenderness at RLQ | Distend, generalized guarding | Soft, not tender | |

| Investigations | US - no intussuscep-tion | Hyponatremia MRI/MRA - no vasculitis, CSF fluid - normal | Normal EEG | US - Diffuse small bowel wall thickening, minimal ascites, no intussuscep-tion | Radiograph - no free air, CT - bowel wall thickening, normal homogeneous enhancement | Radiograph - intraperitoneal free air | ||

| IVMP (mg/kg/d) | 2 | 1 | 30 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Switch to oral prednisolone |

| Treatment | Nexium, sucralfate | ET tube, 3% NaCl, Keppra, Refer | Extubation, off Keppra | NPO, IVIG 2 gm/kg/dose | NPO | NPO, ATB, exploratory laparotomy |

This patient developed intestinal perforation due to a bowel ischemia-related ulcer at day 17 after the onset of disease despite receiving corticosteroid and IVIG therapy. HSP-associated intestinal perforation is a rare complication with an estimated prevalence of 0.38%[2]. To the best of our knowledge, only 11 pediatric cases have been reported in the English literature (Table 2). The most common site of perforation is the small intestine, particularly the ileum followed by the jejunum. The pathogenesis of bowel perforation may result from vasculitis-induced thrombosis, leading to ischemia and consequently total necrosis of the bowel wall[1]. In addition, intussusception and spontaneous bowel perforation can concurrently occur in children with HSP[3-6].

| Ref. | Age (yr) | Sex | Interval between the onset of symptoms and perforation | Location of the perforation | Associated findings | Treatment before perforation | Symptoms before perforation | Reason for surgery | Outcome |

| Choong et al[1] | 5.0 | M | 16 d | Ileum | Intussusception (ileocolic) | Prednisolone | Fever | Peritonitis Subphrenic free air | Survive |

| Shiohama et al[6] | 7.0 | M | 15 d | Distal ileum | No | Prednisolone | Melena | Abdominal rigidity | Survive |

| Free air below the right diaphragm | |||||||||

| 11.0 | M | 11 d | Jejunum and ileum | No | Prednisolone | Melena, hematemesis | Free air in peritoneal cavity | Death | |

| Başaran et al[9] | 4.5 | M | > 15 d | Ileum | Intussusception (ileoileal) | NA | NA | Generalized peritonitis | Death |

| 8.5 | M | > 10 d | Distal ileum | Small bowel adhesions | Prednisolone | NA | Peritonitis | Death | |

| Blachar et al[10] | 5.0 | M | 28 d | Distal ileum | Intussusception (jejunojejunal) | Hydrocortisone | Hematochezia, hematemesis, fever | Peritonitis | Survive |

| Reginelli et al[11] | 4.0 | F | 19 d | Ileum | Bowel necrosis | Cortisol hemisuccinate | Melena, fever | Peritonitis | Survive |

| Rodriguez-Erdmann et al[12] | 5.0 | M | > 12 d | Proximal ileum | Intussusception (ileocolic) | Prednisolone | Fever | Abdominal rigidity Pneumoperitoneum | Survive |

| Law et al[13] | 3.0 | M | 4 wk | Ileum | Ileal stricture | Prednisolone | Fever | Peritonitis | Survive |

| Yigiter et al[14] | 13.0 | M | 7 d | Ileum | Ileal necrosis | Prednisolone | Bile-stained vomiting, bloody stools | Abdominal rigidity Pneumoperitoneum | Death |

| Wang et al[15] | 5.0 | F | 22 d | Terminal ileum | Intestinal necrosis, and adhesion | Broad spectrum antibiotics | Abdominal bulge | Peritonitis Subphrenic free air | Death |

| This case | 4.0 | M | 21 d | Ileum | Intestinal ischemia, necrosis | IVMP | Hematochezia, RLQ pain and guarding | Peritonitis Subphrenic free air | Survive |

| IVIG |

Treatment of HSP remains controversial. Patients with mild GI disease may recover without any therapy. Corticosteroids have been used in patients with moderate to severe GI involvement as the standard therapy, whereas IVIG is an alternative treatment for steroid-resistant disease[7,8]. Other reported treatment for refractory GI diseases in HSP were plasma exchange and immunosuppressive drugs, including cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, and cyclosporine[9]. Early corticosteroid therapy in HSP patients results in better resolution of abdominal pain within 24 h and reduces the risk of persistent renal disease[8]. In contrast, some studies demonstrated that corticosteroids may increase the risk of bowel perforation through the reduction of mucosal renewal and lymphoid patches[2]. A presentation of persistent severe abdominal pain despite corticosteroid therapy is uncommon and could be due to refractory disease, intussusception and intestinal ischemia. In our case, we postulated that vasculitis-induced mucosal ischemia was the cause of the ulcer which subsequently perforated, leading to diffuse peritonitis. Based on the histopathological findings of granulation tissue and fibrosis at the base of ulcer, we inferred that the perforation happened some time prior to surgery. However, the exact time of perforation cannot be accurately estimated. It is likely that he had concealed bowel perforation, masking the symptoms and signs and leading to a delay in detecting the bowel perforation. We also speculated that high-dose corticosteroid treatment was a contributing factor due to reducing mucosal lymphoid follicles (Peyer’s patches) and compromising mucosal renewal and healing.

Early detection of intestinal ischemia is crucial for early surgical resection. Delayed diagnosis can result in intestinal perforation and peritonitis which are severe and life-threatening complications. Unfortunately, the signs and symptoms of intestinal ischemia are not specific, ranging from decreased bowel sound, abdominal tenderness, abdominal distension, to hematochezia. Moreover, some patients had transient improvement during the course of disease[2]. The gold standard investigation for intestinal ischemia is arteriography but it is invasive and difficult to perform in children. CT scan, particularly multidetector computed tomography, is a major investigation in the diagnosis of bowel ischemia. The diagnostic findings in CT scan include decreased or absent bowel wall enhancement and intramural gas in the bowel wall, however, these findings are found infrequently. Frequent findings are thickening of intestinal wall, dilatation of lumen, and intra-abdominal fluid, which cannot be differentiated from other diseases[10]. Therefore, bowel ischemia cannot be excluded based on the absence of intramural gas in the bowel wall from a contrast-enhanced CT scan, as seen in this patient. A plain abdominal radiograph is useful only in cases of perforation but it could not detect bowel ischemia. Abdominal ultrasound is more frequently used to identify other abdominal pathology, such as intussusception and bowel perforation. However, this technique is limited if the patient has a large amount of air in the bowel loops. Ultrasonography may be useful in the late phase of ischemic bowel by demonstrating bowel wall thickening, a fluid-filled lumen, decreased or absent bowel movement, and extra-luminal fluid[11]. Since bowel perforation can occur at 1 to 4 wk after initial presentation[1,6,9-15], close observation and frequent physical examination are essential for the early detection of bowel ischemia, especially when the patients have hematochezia, persistent localized abdominal tenderness, and guarding. Finally, in highly suspicious patients, exploratory laparotomy may be needed for the definite diagnosis and treatment of intestinal ischemia and bowel perforation.

In conclusion, HSP is generally a self-limited disease and rarely requires surgical intervention. Corticosteroid therapy is indicated in moderate to severe GI involvement. Persistent severe abdominal pain after initiating corticosteroid therapy is uncommon and physicians should be concerned about GI complications. Bowel ischemia and perforation are rare but life-threatening conditions. Therefore, early diagnosis by clinical evaluation and proper investigations, and prompt surgical treatment are necessary for decreasing morbidity and mortality in these patients.

The authors thank Dr. Mahippathorn Chinnapha and Adam Dale, a native speaker of English with former journalism experience now working as an English language Instructor at IGenius Language Institute for proofreading the English.

A 4-year-old Thai boy, who was diagnosed with Henoch Schönlein purpura (HSP), had persistent severe abdominal pain despite receiving corticosteroid therapy.

Physical examination revealed abdominal distention, localized guarding and tenderness.

Gastrointestinal vasculitis from refractory HSP, intussusception, intestinal ischemia.

Acute phase reactants were elevated.

Upright abdominal radiograph demonstrated intraperitoneal free air.

A large perforated ulcer with fibrofibrinous exudates and the remaining bowel showed depletion of lymphoid follicles (Peyer’s patch), submucosal and subserosal congestion and diffuse peritonitis.

Exploratory laparotomy with ileal resection and end to end ileoileosanastomosis.

HSP with intestinal perforation is a rare condition. To the best of our knowledge, only 11 pediatric cases have been reported in the English literature. The literature reports showed that bowel perforation can occur 1 to 4 wk after initial presentation.

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion is the condition that causes increased secretion or enhanced antidiuretic hormone, resulting in excess fluid in the body and leading to hyponatremia.

Despite adequate corticosteroid therapy and non-specific findings in the abdominal computed tomography, intestinal ischemia could not be excluded especially in HSP patients with hematochezia, persistent severe abdominal pain and localized guarding.

This is a very interesting case report and review of the literature. The authors did a very nice job of presenting all of the pertinent information from the case. Additionally, the discussion was well-balanced and provided needed information. The table and figures were also appropriate for the case and manuscript. Even if the manuscript doesn’t present important new methods or novel findings, it reminds pediatricians and gastroenterologists that close observation and frequent physical examination are essential for the early detection of bowel ischemia as possible cause of bowel perforation.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

P- Reviewer: Caronna R, Chen JQ, Swanson JR S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Choong CK, Beasley SW. Intra-abdominal manifestations of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. J Paediatr Child Health. 1998;34:405-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yavuz H, Arslan A. Henoch-Schönlein purpura-related intestinal perforation: a steroid complication? Pediatr Int. 2001;43:423-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | BASU R. Perforation of the bowel in Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Arch Dis Child. 1959;34:342-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lindenauer SM, Tank ES. Surgical aspects of Henoch-Schönlein’s purpura. Surgery. 1966;59:982-987. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Martinez-Frontanilla LA, Haase GM, Ernster JA, Bailey WC. Surgical complications in Henoch-Schönlein Purpura. J Pediatr Surg. 1984;19:434-436. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Shiohama T, Kitazawa K, Omura K, Honda A, Kozuki A, Tanaka N, Omata A, Ooe K, Suzuki Y. Intussusception and spontaneous ileal perforation in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Pediatr Int. 2008;50:709-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yang HR, Choi WJ, Ko JS, Seo JK. Intravenous immunoglobulin for severe gastrointestinal manifestation of Henoch-Schonlein purpura refractory to corticosteroid therapy. Korean J Pediatr. 2006;49:784-789. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Weiss PF, Feinstein JA, Luan X, Burnham JM, Feudtner C. Effects of corticosteroid on Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1079-1087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Başaran Ö, Cakar N, Uncu N, Çelikel BA, Kara A, Cayci FS, Taktak A, Gür G. Plasma exchange therapy for severe gastrointestinal involvement of Henoch Schönlein purpura in children. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:S-176-S-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Blachar A, Barnes S, Adam SZ, Levy G, Weinstein I, Precel R, Federle MP, Sosna J. Radiologists’ performance in the diagnosis of acute intestinal ischemia, using MDCT and specific CT findings, using a variety of CT protocols. Emerg Radiol. 2011;18:385-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Reginelli A, Genovese E, Cappabianca S, Iacobellis F, Berritto D, Fonio P, Coppolino F, Grassi R. Intestinal Ischemia: US-CT findings correlations. Crit Ultrasound J. 2013;5 Suppl 1:S7. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Rodriguez-Erdmann F, Levitan R. Gastrointestinal and roentgenological manifestations of Henoch-Schoenlein purpura. Gastroenterology. 1968;54:260-264. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Law F, Davidson PM, Robinson M, Stokes KB. Ileal perforation: a late surgical complication of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Pediatr Surg Int. 1987;2:187-188. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Yigiter M, Bosnali O, Sekmenli T, Oral A, Salman AB. Multiple and recurrent intestinal perforations: an unusual complication of Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2005;15:125-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang HL, Liu HT, Chen Q, Gao Y, Yu KJ. Henoch-Schonlein purpura with intestinal perforation and cerebral hemorrhage: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2574-2577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |