Published online Jun 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i22.5246

Peer-review started: February 19, 2016

First decision: March 9, 2016

Revised: April 5, 2016

Accepted: April 15, 2016

Article in press: April 15, 2016

Published online: June 14, 2016

Processing time: 106 Days and 6.8 Hours

AIM: To identify rates of post-discharge complications (PDC), associated risk factors, and their influence on early hospital outcomes after esophagectomy.

METHODS: We used the 2005-2013 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database to identify patients ≥ 18 years of age who underwent an esophagectomy. These procedures were categorized into four operative approaches: transhiatal, Ivor-Lewis, 3-holes, and non-gastric conduit. We selected patient data based on clinical relevance to patients undergoing esophagectomy and compared demographic and clinical characteristics. The primary outcome was PDC, and secondary outcomes were hospital readmission and reoperation. The patients were then divided in 3 groups: no complication (Group 1), only pre-discharge complication (Group 2), and PDC patients (Group 3). A modified Poisson regression analysis was used to identify risk factors associated with developing post-discharge complication, and risk ratios were estimated.

RESULTS: 4483 total patients were identified, with 8.9% developing PDC within 30-d after esophagectomy. Patients who experienced complications post-discharge had a median initial hospital length of stay (LOS) of 9 d; however, PDC occurred on average 14 d following surgery. Patients with PDC had greater rates of wound infection (41.0% vs 19.3%, P < 0.001), venous thromboembolism (16.3% vs 8.9%, P < 0.001), and organ space surgical site infection (17.1% vs 11.0%, P = 0.001) than patients with pre-discharge complication. The readmission rate in our entire population was 12.8%. PDC patients were overwhelmingly more likely to have a reoperation (39.5% vs 22.4%, P < 0.001) and readmission (66.9% vs 6.6%, P < 0.001). BMI 25-29.9 and BMI ≥ 30 were associated with increased risk of PDC compared to normal BMI (18.5-25).

CONCLUSION: PDC after esophagectomy account for significant number of reoperations and readmissions. Efforts should be directed towards optimizing patient’s health pre-discharge, with possible prevention programs at discharge.

Core tip: In this study, we used the 2005-2013 ACS-NSQIP database to identify the rate of post-discharge complications, their associated risk factors, and their influence on early hospital readmission after esophagectomy. This report demonstrates that post-discharge complications after esophagectomy account for a significant number of reoperations and readmissions. We believe that implementing prevention strategies to decrease common post-discharge complications like venous thromboembolism and infection should be considered, and that directing our energies toward optimizing patient health prior to discharge may improve overall surgical outcomes.

- Citation: Chen SY, Molena D, Stem M, Mungo B, Lidor AO. Post-discharge complications after esophagectomy account for high readmission rates. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(22): 5246-5253

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i22/5246.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i22.5246

Esophagectomy is the mainstay treatment for localized esophageal carcinoma without medical contraindications[1]. It can also be indicated for certain benign conditions, including high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus, caustic ingestion, reflux esophagitis complications, esophageal stricture, and esophageal neuromotor dysfunction (achalasia, spasm, scleroderma)[2]. Over 5000 esophagectomies are performed in the United States and United Kingdom annually[3]. Despite improved surgical techniques and intensive care unit therapy[4], post-esophagectomy mortality and morbidity rates remain suboptimal, ranging from 7%-28%[5,6] and 10%-27%[7], respectively. Moreover, readmission rates after esophagectomy range from 5%-25%[8,9], and the overall 5-year survival rate following esophagectomy range from 15%-40%[10,11].

These dismal outcomes after esophagectomy, compounded with national health policy changes by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Affordable Care Act that emphasize reducing hospital readmission rates to improve health care quality, have spurred growing interest in investigating quality measures related to esophagectomy. Although several studies have explored esophagectomy complications and readmission[12-16] none to date have delved into risk factors associated specifically with post-discharge complications (PDC) after esophagectomy. Given that approximately a third of post-operative surgical complications occur post-discharge, and that PDC may differ from pre-discharge complications[17], we hypothesize that several clinical factors may increase risk for developing PDC after esophagectomy.

Using 2005-2013 data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP), we sought to identify the rate of PDC, their associated risk factors, and their influence on early hospital outcomes including readmission and reoperation. We believe that understanding these risk factors will provide additional insights to improve esophagectomy quality outcomes.

This study is a retrospective analysis using the 2005-2013 ACS-NSQIP database. ACS-NSQIP is a nationally-validated, risk-adjusted, and outcomes-based program created for the purpose of measuring and improving surgical quality care[18,19]. The program collects data on patients undergoing surgery from over 650 participating hospitals of varying size and academic affiliation[20]. Eligibility criteria for hospital participation include: hiring a surgical clinical reviewer who uses a standardized format to capture and review data from clinical records, identifying a Surgeon Champion to lead the program at the hospital, agreeing to program protocols, meeting minimum case standards, and paying an annual participation fee to ACS. Prospective, systematic data collection is performed on 150 preoperative and intraoperative variables, in addition to 30-d postoperative morbidity and mortality. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Patients ≥ 18 years of age who underwent an esophagectomy (defined as current procedural terminology codes 43107, 43108, 43112, 43113, 43117, 43118, 43121, 43122, or 43123) were included. These procedures were then categorized into four operative approaches: transhiatal (if the chest was not entered and the stomach was used as a conduit), Ivor-Lewis (if the anastomosis was done in the chest and the stomach was used as a conduit), 3-holes (if the anastomosis was done in the neck, the chest was entered and the stomach was used as a conduit), and intestinal conduit (if any of the above approaches were used but intestine, either large or small, was used as a conduit). Patients who had missing data for days from operation to discharge, and days from operation to complication (for patients who had complication) were excluded. Patients who were not discharged within 30-d of operation were also excluded. Lastly, patients who died during initial hospitalization were excluded from the analysis that aimed to identify risk factors associated with PDC (univariate logistic regression), as these patients were not at risk for PDC.

We selected patient data based on clinical relevance to patients undergoing esophagectomy and compared demographic and clinical characteristics. Three groups of patients were defined: no complication (Group 1), only pre-discharge complication (Group 2), and PDC patients (Group 3). Patients with esophageal/gastric cancer were defined with a diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, codes of 150, 150.1, 150.2, 150.3, 150.4, 150.5, 150.8, 150.9, 151, 151.0).

The primary outcome was PDC, which we defined as an event for which the time interval (days) between the initial operation and a complication was greater than the interval from operation to discharge. The secondary outcomes included hospital readmission (2011-2013) and reoperation (2012-2013). Complication types included from ACS-NSQIP were investigated. Prolonged length of stay and prolonged operative time, defined as stay or time greater than the 75th percentile, respectively, were also investigated.

Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. Student’s t-test or ANOVA were used to compare continuous variables. Modified Poisson regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with developing a PDC, and risk ratios (RR) were estimated. A P-value of P < 0.05 was determined statistically significant. We performed all data analyses and management using Stata/MP version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, United States).

A total of 4872 patients underwent esophagectomy between 2005 and 2013. However, 389 (7.98%) patients were not discharged before the 30-day period and were excluded for this very reason. 4483 patients represented our study population, including 2497 (55.7%) patients who had no postoperative complications, 1588 (35.4%) who had at least one pre-discharge complication, and 398 (8.9%) who had at least one PDC. The mean age was 63.1 years, with 80.0% male and 85.9% whites. The mean BMI was 27.9 kg/m2. PDC patients tended to be slightly older with greater ASA class, BMI, and more comorbidities including diabetes and, dyspnea compared to no complication group (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | P value |

| No complication | Pre-discharge complication | Post-discharge complication | ||

| n = 2497 (55.70) | n = 1588 (35.42) | n = 398 (8.88) | ||

| Age, mean (median) | 62.5 ± 11.2 (63) | 63.9 ± 10.8 (65) | 63.4 ± 10.9 (64) | 0.001 |

| Age group (yr) | 0.048 | |||

| < 60 | 921 (36.88) | 513 (32.30) | 143 (35.93) | |

| 60-69 | 862 (34.52) | 579 (36.46) | 126 (31.66) | |

| 70-79 | 602 (24.11) | 407 (25.63) | 109 (27.39) | |

| ≥ 80 | 112 (4.49) | 89 (5.60) | 20 (5.03) | |

| Male1 | 2042 (81.88) | 1220 (76.83) | 325 (81.66) | < 0.001 |

| Race | 0.088 | |||

| White | 2135 (85.50) | 1363 (85.83) | 352 (88.44) | |

| Black | 76 (3.04) | 62 (3.90) | 6 (1.51) | |

| Other/unknown | 286 (11.45) | 168 (10.26) | 40 (10.05) | |

| ASA classification1 | < 0.001 | |||

| No disturb/mild disturb | 611 (24.50) | 237 (14.92) | 88 (22.17) | |

| Serious disturb | 1746 (70.01) | 1161 (73.11) | 269 (67.76) | |

| Life threat/moribund | 137 (5.49) | 190 (11.96) | 40 (10.08) | |

| Body mass index, mean (median) | 27.9 ± 6.4 (27) | 27.7 ± 6.3 (26.9) | 28.4 ± 6.2 (27.6) | 0.132 |

| Body mass index group1 (kg/m2) | 0.013 | |||

| < 18.5 | 68 (2.75) | 59 (3.75) | 9 (2.26) | |

| 18.5-24.9 | 761 (30.72) | 522 (33.14) | 100 (25.13) | |

| 25-29.9 | 905 (36.54) | 532 (33.78) | 159 (39.95) | |

| ≥ 30 | 743 (30.00) | 462 (29.33) | 130 (32.66) | |

| Diabetes | 341 (13.66) | 300 (18.89) | 75 (18.84) | < 0.001 |

| Current smoker | 616 (24.67) | 434 (27.33) | 86 (21.61) | 0.033 |

| Dyspnea | 209 (8.37) | 205 (12.91) | 48 (12.06) | < 0.001 |

| History of COPD | 131 (5.25) | 156 (9.82) | 23 (5.78) | < 0.001 |

| Weight loss | 468 (18.74) | 301 (18.95) | 73 (18.34) | 0.959 |

| Steroid use | 74 (2.96) | 42 (2.64) | 12 (3.02) | 0.820 |

| Emergency case | 18 (0.72) | 39 (2.46) | 3 (0.75) | < 0.001 |

| Diagnosis | 0.002 | |||

| Benign disease | 355 (14.22) | 289 (18.20) | 56 (14.07) | |

| Esophageal/gastric cancer | 2142 (85.78) | 1299 (81.80) | 342 (85.93) | |

| Year of operation | 0.012 | |||

| 2005-2007 | 293 (11.73) | 223 (14.04) | 41 (10.30) | |

| 2008-2010 | 746 (29.88) | 409 (25.76) | 109 (27.39) | |

| 2011-2013 | 1458 (58.39) | 956 (60.20) | 248 (62.31) |

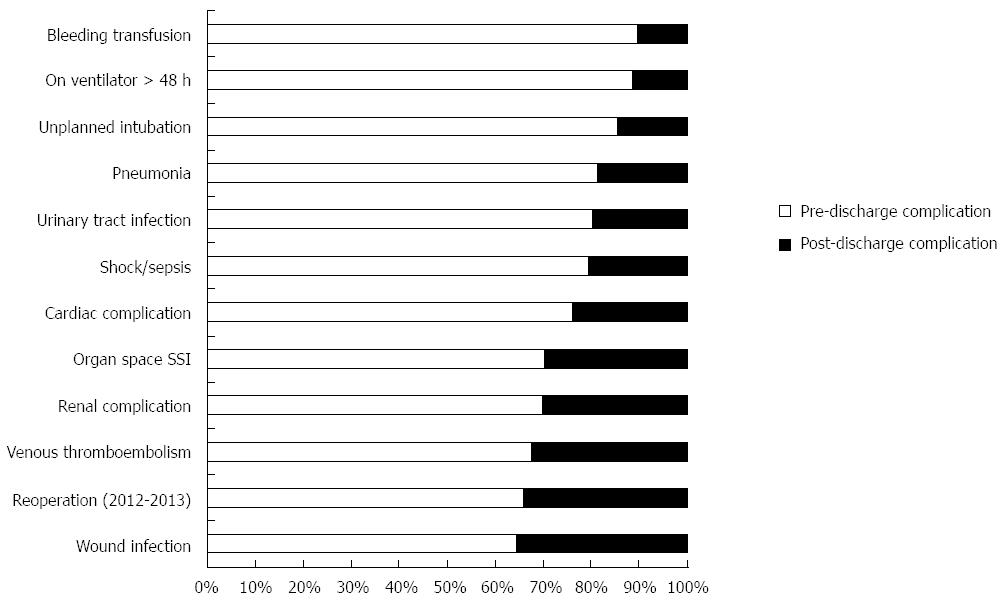

The overall PDC rate was 8.9%. Patients who experienced PDC had a median initial length of hospital stay of 9 d; however, PDC occurred on average 14 d after surgery. Among procedure types, PDC rates were 35.7% for transhiatal, 34.1% for Ivor Lewis, 36.9% for 3-holes, and 44.3% for intestinal conduit. Interestingly, PDC rates remained similar over the studied years (8.3% in 2005-2006 vs 8.9% in 2013) (Figure 1). Of the patients who experienced PDC, 127 of them (31.9%) also had pre-discharge complications. The overall readmission rate (2011-2013) after esophagectomy was 12.8%. Only from 2012 NSQIP identified if readmissions were likely related to the principle surgical procedure. There were 253 readmissions (253/1989, 12.72%) between 2012 and 2013 and 83.8% (212/253) of these readmissions were related to the initial surgical procedure. PDC patients were overwhelmingly more likely to have a reoperation (39.5% vs 22.4% for 2012-2013, P < 0.001) and to be readmitted (66.9% vs 6.6% for 2011-2013, P < 0.001). Moreover, pre-discharge and PDC differed by complication types (Figure 2). PDC patients had greater rates of wound infection (41.0% vs 19.3%), VTE (16.3% vs 8.9%), and organ space SSI (17.1% vs 11.0%) (P≤ 0.001 for each) than pre-discharge complication patients (Table 2). Although 30-day mortality rates were greater for patients who experienced PDC, this finding was not statistically significant.

| Outcome | Total (n = 1986) | Group 2 | Group 3 | P value |

| Pre-discharge complication | Post-discharge complication | |||

| n = 1588 (79.96) | n = 398 (20.04) | |||

| 30-d mortality1 | 140 (7.05) | 104 (6.55) | 36 (9.05) | 0.082 |

| Overall morbidity | ||||

| Wound infection | 470 (23.67) | 307 (19.33) | 163 (40.95) | < 0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 535 (26.94) | 444 (27.96) | 91 (22.86) | 0.040 |

| Urinary tract infection | 112 (5.64) | 91 (5.73) | 21 (5.28) | 0.725 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 207 (10.42) | 142 (8.94) | 65 (16.33) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiac complication | 108 (5.44) | 92 (5.79) | 16 (4.02) | 0.163 |

| Shock/sepsis | 518 (26.08) | 422 (26.57) | 96 (24.12) | 0.319 |

| Unplanned intubation | 420 (21.15) | 368 (23.17) | 52 (13.07) | < 0.001 |

| Bleeding transfusion | 584 (29.41) | 526 (33.12) | 58 (14.57) | < 0.001 |

| Renal complication | 59 (2.97) | 50 (3.15) | 9 (2.26) | 0.351 |

| On ventilator > 48 h | 439 (22.10) | 396 (24.94) | 43 (10.80) | < 0.001 |

| Organ space SSI | 242 (12.19) | 174 (10.96) | 68 (17.09) | 0.001 |

| Reoperation 12-13 | 235 (25.97) | 160 (22.38) | 75 (39.47) | < 0.001 |

| Serious Morbidity2 | 1102 (55.49) | 901 (56.74) | 201 (50.50) | 0.025 |

| Year of operation | 0.142 | |||

| 2005-2007 | 264 (13.29) | 223 (14.04) | 41 (10.30) | |

| 2008-2010 | 518 (26.08) | 409 (25.76) | 109 (27.39) | |

| 2011-2013 | 1204 (60.62) | 956 (60.20) | 248 (62.31) | |

| Length of stay, d (median) | 11.7 ± 5.4 (10) | 15.0 ± 6.3 (14) | 10.3 ± 4.3 (9) | < 0.001 |

| Prolonged length of stay3 | 765 (38.52) | 707 (44.52) | 58 (14.57) | < 0.001 |

| Operative time, min (median) | 342.3 ± 134.7 (328) | 358.6 ± 145.6 (343) | 350.4 ± 133.1 (335.5) | 0.308 |

| Prolonged operative time4 | 570 (28.70) | 467 (29.41) | 103 (25.88) | 0.164 |

| Readmission 2011-2013 | 226 (19.07) | 62 (6.60) | 164 (66.94) | < 0.001 |

Univariate modified Poisson regression analysis revealed that greater BMI, specifically BMI 25-29.9 (RR = 1.37, 95%CI: 1.08-1.74) and BMI ≥ 30 (RR = 1.34, 95%CI: 1.04-1.72), were associated with increased risk of PDC, compared to normal BMI (18.5-25) (Table 3).

| Risk factor | PDC risk (n/total) | RR (95%CI) |

| Overall PDC risk | 398/4379 (9.09) | - |

| Procedure type | ||

| Ivor-Lewis | 196/2219 (8.83) | Ref |

| Transhiatal | 115/1261 (9.12) | 1.03 (0.83-1.29) |

| 3-holes | 66/730 (9.04) | 1.02 (0.78-1.34) |

| Intestinal conduit | 21/169 (12.43) | 1.41 (0.92-2.15) |

| Age group (%) | ||

| < 60 | 143/1562 (9.15) | Ref |

| 60-69 | 126/1529 (8.24) | 0.90 (0.72-1.13) |

| 70-79 | 109/1082 (10.07) | 1.10 (0.87-1.39) |

| ≥ 80 | 20/206 (9.71) | 1.06 (0.68-1.65) |

| Male (%) | 325/3505 (9.27) | 1.11 (0.87-1.41) |

| Race (%) | ||

| White | 352/3763 (9.35) | Ref |

| Black | 6/137 (4.38) | 0.46 (0.21-1.00) |

| Other/unknown | 40/479 (8.35) | 0.89 (0.65-1.22) |

| ASA classification (%) | ||

| No disturb/mild disturb | 88/930 (9.46) | Ref |

| Serious disturb | 269/3104 (8.67) | 0.92 (0.73-1.15) |

| Life threat/moribund | 40/341 (11.73) | 1.24 (0.87-1.76) |

| Body mass index (%) | ||

| 18.5-24.9 | 100/1347 (7.42) | Ref |

| < 18.5 | 9/129 (6.98) | 0.94 (0.49-1.81) |

| 25-29.9 | 159/1561 (10.19) | 1.37 (1.08-1.74) |

| ≥ 30 | 130/1310 (9.92) | 1.34 (1.04-1.72) |

| Diabetes (%) | 75/692 (10.84) | 1.24 (0.98-1.57) |

| Current smoker (%) | 86/1111 (7.74) | 0.81 (0.64-1.02) |

| Dyspnea (%) | 48/436 (11.01) | 1.24 (0.93-1.65) |

| History of COPD (%) | 23/297 (7.74) | 0.84 (0.56-1.26) |

| Weight loss (%) | 73/812 (8.99) | 0.99 (0.77-1.26) |

| Steroid use (%) | 12/124 (9.68) | 1.07 (0.62-1.84) |

| Emergency case | 3/52 (5.77) | 0.63 (0.21-1.90) |

| Esophageal/gastric cancer (%) | 342/3707 (9.23) | 1.11 (0.84-1.45) |

| Prolonged length of stay1 (%) | 58/938 (6.18) | 0.63 (0.48-0.82) |

| Prolonged operative time2 (%) | 103/1087 (9.48) | 1.06 (0.85-1.31) |

Although several studies have investigated postoperative complications and readmissions following esophagectomy, none to our knowledge have explored the distinct role of PDC on early hospital outcomes. This is the first study to use ACS-NSQIP to examine the rate of PDC, their associated risk factors, and their influence on early hospital outcomes after esophagectomy. ACS-NSQIP offers a unique opportunity to assess at a national, multi-institutional level these specific health quality measures that may be unavailable in other large, population-level databases. Our retrospective analysis demonstrates that PDC occur at a low rate but account for a significant number of reoperations and readmissions. Higher BMIs were associated with increased risk of PDC. PDC were different than pre-discharge complications and potentially preventable.

Of the patients with PDC, wound infection, pneumonia, and VTE were among common PDC that could serve as targeted areas for quality improvement. These PDC are consistent with prior studies examining perioperative complications after esophagectomy[21,22]. Interventions to reduce PDC, such as adopting best practices to prevent wound infection and VTE, may improve esophagectomy outcomes. In one study, selective anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis using a DVT risk factor index significantly decreased DVT rates after esophageal cancer surgery[23]. Another study showed that low molecular weight heparin prophylaxis resulted in a 72% reduction in DVT risk after general surgery[24]. These suggest that efforts aimed to reduce common complications after surgery may also be effective and applicable to esophagectomy and should be continued after discharge. Interestingly, PDC rates have remained similar over the studied years, revealing likely no significant changes in practice or indications.

Our modified Poisson regression analysis demonstrates several factors that may increase the risk of PDC and therefore enable us to stratify higher-risk patients for perioperative risk assessment. These include patients with BMI 25.0-29.9 and BMI ≥ 30, compared to normal BMI 18.5-25.0. Although obesity is associated with higher incidence of medical comorbidities like hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease[25], the association of BMI and complications after esophagectomy is conflicting. Several studies have suggested that overweight and obese patients may have increased risk for complications after esophagectomy, such as longer operative times[26] and greater risks for anastomotic leaks[27], respiratory complications[27], and surgical site infections[28]. However, other studies have shown that obese patients do not have more postoperative complications and longer hospital stays compared to non-obese patients[14,29,30]. Several routine measures implemented in the hospital setting to decrease the most common post-operative complications (i.e., early mobilization, incentive spirometry and pulmonary toilet, DVT prophylaxis, daily dressing changes) are not continued after discharge, and the lack of preventive actions may impact obese patients more than non-obese. As such, appropriate interventions for higher BMI patients may be beneficial and may include enhanced perioperative management of patient comorbidities, preoperative risk stratification, additional patient education, continuation of pulmonary toilet, exercise programs, and DVT prophylaxis after discharge and earlier follow-up. For example, one study has shown that performing preoperative risk analysis on pulmonary function and general status when selecting patients for transthoracic esophagectomy reduced postoperative morbidity rates[31]. Interventions targeting higher BMI patients undergoing esophagectomy may therefore reduce PDC rates.

We decided to separate the patients with pre-discharge complications to keep our groups as homogeneous as possible for fair comparison. Since these patients have a longer hospital stay (median LOS 14 d), a 30-d follow-up may not be long enough to record PDC. It was interesting, however, to see that the most common types of PDC are different than those occurring in the initial post-operative period. This information is helpful to the physician to identify patients at risk of PDC and to plan preventative measures.

The overall readmission rate in our study is 12.8%, consistent with another study’s rate of 18.6%[12]. From our study, 39.5% of PDC patients underwent reoperation (2012-2013) compared to 22.4% of pre-discharge complication patients. This suggests that reoperation may have been indicated due to complications that developed after discharge and subsequent delays in management. Even more striking is our finding that 66.9% of PDC patients were readmitted, compared to 6.6% of pre-discharge complication patients. Recent changes in health policy and reimbursements have brought issues of health care costs to the forefront, resulting in some hospital administrations advocating for earlier discharge of patients. Readmission has become a major focus from health care quality and cost-savings standpoints. However, the use of readmission as a quality metric is still debatable[32,33]. In the case of esophagectomy, efforts to reduce costs by promoting earlier discharge may increase readmission[16], reoperation, and PDC rates; hospital readmission after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer is also associated with poor survival[12]. One study has shown that postoperative complications lead to greater readmission rates after colon resection[34]. In bariatric surgery patients, PDC account for a substantial source of patient morbidity and readmissions[17]. Rather than emphasizing shorter hospital lengths of stay, putting more energy into preventing complications after esophagectomy, and optimizing patient health prior to discharge instead may lead to improved surgical quality outcomes and reduced hospital spending.

Despite the advantages of ACS-NSQIP, the database does pose some limitations to our study. ACS-NSQIP does not contain consistent information on tumor histology, margins, stage, surgical history, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (within 30 d preoperatively), and neoadjuvant radiation (within the last 90 d) that could otherwise provide greater context in interpreting our results. Several complications common to esophagectomy, such as anastomotic leaks, chyle leak, and delayed gastric emptying, are not captured in the database. ACS-NSQIP also identifies 30-d postoperative readmission rather than 30-d post-discharge readmissions, which may introduce immortal person-time bias and lead to shorter number of follow-up days for patients with longer hospital stays. Although PDC could lead to greater mortality, because ACS-NSQIP does not capture data beyond 30-d postoperatively, further studies examining long-term outcomes including mortality is warranted. Readmission data is available only from 2011-2013, but the large patient sample population within that cohort should prevent significant alterations in our conclusions. It is also uncertain whether our findings are applicable to all hospital settings, as hospital participation is voluntary and comprised primarily of academic, tertiary-care centers. Hospital size, setting, patient volume, teaching status, and individual surgeon experience also cannot be adjusted for.

In summary, PDC after esophagectomy account for a significant number of reoperations and readmissions. Adopting best practices to reduce common PDC like VTE and infection, and performing interventions for higher-risk individuals such as those with high BMI, should therefore be considered.

The authors would like to thank Mr. Edwin Lewis for his generous support of Dr. Lidor’s Department of Surgery Research Fund.

Esophagectomy is the mainstay treatment for esophageal carcinoma and can also be indicated for benign conditions with end-stage organ dysfunction or perforation. Despite improved surgical and medical care, post-esophagectomy mortality and morbidity rates remain suboptimal. Such disappointing outcomes after esophagectomy, compounded with national health policy changes that emphasize reducing hospital readmission rates and improving health care quality, have spurred growing interest in investigating quality measures related to esophagectomy. Using 2005-2013 data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP), we sought to identify the rate of post-discharge complications, their associated risk factors, and their influence on early hospital outcomes including readmission and reoperation.

Although several studies have explored post-esophagectomy complications and readmission, none to date have delved into specifics of post-discharge complications and risk factors associated with them. The results from this study offer additional insights to improve esophagectomy quality outcomes.

No other studies have investigated the specific outcomes of post-discharge complications after esophagectomy. In this study, The authors demonstrated that post-discharge complications after esophagectomy occur a median of 14 d postoperatively and account for a significant number of reoperations and readmissions. Moreover, pre- and post-discharge complications differed by type, with venous thromboembolism and infection occurring more commonly after discharge.

These research findings can be applied to predict, identify, and prevent adverse outcomes in patients who have undergone esophagectomies. Implementing strategies to decrease common post-discharge complications like venous thromboembolism and infection should be considered, and directing our energies toward optimizing patient health prior to discharge may improve overall surgical outcomes.

This is a review of the ACS-NSQIP esophagectomy database, meant to identify post-discharge complications. It has a huge sample, a clear presentation and analysis, and an interesting discussion. It is without doubt an important topic deserving of evaluation.

P- Reviewer: del Val ID, Motoyama S, Narayanan S, Stiles BM S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Wu PC, Posner MC. The role of surgery in the management of oesophageal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:481-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kim SH, Lee KS, Shim YM, Kim K, Yang PS, Kim TS. Esophageal resection: indications, techniques, and radiologic assessment. Radiographics. 2001;21:1119-1137; discussion 1138-1140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rodgers M, Jobe BA, O’Rourke RW, Sheppard B, Diggs B, Hunter JG. Case volume as a predictor of inpatient mortality after esophagectomy. Arch Surg. 2007;142:829-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Law S, Wong KH, Kwok KF, Chu KM, Wong J. Predictive factors for postoperative pulmonary complications and mortality after esophagectomy for cancer. Ann Surg. 2004;240:791-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kohn GP, Galanko JA, Meyers MO, Feins RH, Farrell TM. National trends in esophageal surgery--are outcomes as good as we believe? J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1900-1910; discussion 1910-1912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2128-2137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1119] [Cited by in RCA: 1066] [Article Influence: 76.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rutegård M, Lagergren P, Rouvelas I, Lagergren J. Intrathoracic anastomotic leakage and mortality after esophageal cancer resection: a population-based study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:99-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Goodney PP, Stukel TA, Lucas FL, Finlayson EV, Birkmeyer JD. Hospital volume, length of stay, and readmission rates in high-risk surgery. Ann Surg. 2003;238:161-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Varghese TK, Wood DE, Farjah F, Oelschlager BK, Symons RG, MacLeod KE, Flum DR, Pellegrini CA. Variation in esophagectomy outcomes in hospitals meeting Leapfrog volume outcome standards. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:1003-1009; discussion 1009-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schneider PM, Baldus SE, Metzger R, Kocher M, Bongartz R, Bollschweiler E, Schaefer H, Thiele J, Dienes HP, Mueller RP. Histomorphologic tumor regression and lymph node metastases determine prognosis following neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy for esophageal cancer: implications for response classification. Ann Surg. 2005;242:684-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mariette C, Piessen G, Triboulet JP. Therapeutic strategies in oesophageal carcinoma: role of surgery and other modalities. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:545-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fernandez FG, Khullar O, Force SD, Jiang R, Pickens A, Howard D, Ward K, Gillespie T. Hospital readmission is associated with poor survival after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99:292-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shah SP, Xu T, Hooker CM, Hulbert A, Battafarano RJ, Brock MV, Mungo B, Molena D, Yang SC. Why are patients being readmitted after surgery for esophageal cancer? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149:1384-1389; discussion 1389-1391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wong JY, Shridhar R, Almhanna K, Hoffe SE, Karl RC, Meredith KL. The impact of body mass index on esophageal cancer. Cancer Control. 2013;20:138-143. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Miao L, Chen H, Xiang J, Zhang Y. A high body mass index in esophageal cancer patients is not associated with adverse outcomes following esophagectomy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2015;141:941-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sundaram A, Srinivasan A, Baker S, Mittal SK. Readmission and risk factors for readmission following esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:581-55; discussion 586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chen SY, Stem M, Schweitzer MA, Magnuson TH, Lidor AO. Assessment of postdischarge complications after bariatric surgery: A National Surgical Quality Improvement Program analysis. Surgery. 2015;158:777-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Available from: https://acsnsqip.org/login/default.aspx. |

| 19. | Available from: https://acsnsqip.org/puf/docs/ACS_NSQIP_Participant_User_Data_File_User_Guide.pdf. |

| 20. | American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Participants. Chicago, IL, USA. Available from: http://site.acsnsqip.org/participants/. |

| 21. | Atkins BZ, Fortes DL, Watkins KT. Analysis of respiratory complications after minimally invasive esophagectomy: preliminary observation of persistent aspiration risk. Dysphagia. 2007;22:49-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mukherjee D, Lidor AO, Chu KM, Gearhart SL, Haut ER, Chang DC. Postoperative venous thromboembolism rates vary significantly after different types of major abdominal operations. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:2015-2022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rakić S, Pesko P, Jagodić M, Dunjić MS, Maksimović Z. Venous thromboprophylaxis in oesophageal cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1145-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mismetti P, Laporte S, Darmon JY, Buchmüller A, Decousus H. Meta-analysis of low molecular weight heparin in the prevention of venous thromboembolism in general surgery. Br J Surg. 2001;88:913-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 433] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dindo D, Muller MK, Weber M, Clavien PA. Obesity in general elective surgery. Lancet. 2003;361:2032-2035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 472] [Cited by in RCA: 494] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kilic A, Schuchert MJ, Pennathur A, Yaeger K, Prasanna V, Luketich JD, Gilbert S. Impact of obesity on perioperative outcomes of minimally invasive esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:412-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Healy LA, Ryan AM, Gopinath B, Rowley S, Byrne PJ, Reynolds JV. Impact of obesity on outcomes in the management of localized adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134:1284-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Merry AH, Schouten LJ, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA. Body mass index, height and risk of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and gastric cardia: a prospective cohort study. Gut. 2007;56:1503-1511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Blom RL, Lagarde SM, Klinkenbijl JH, Busch OR, van Berge Henegouwen MI. A high body mass index in esophageal cancer patients does not influence postoperative outcome or long-term survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:766-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zogg CK, Mungo B, Lidor AO, Stem M, Rios Diaz AJ, Haider AH, Molena D. Influence of body mass index on outcomes after major resection for cancer. Surgery. 2015;158:472-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Schröder W, Bollschweiler E, Kossow C, Hölscher AH. Preoperative risk analysis--a reliable predictor of postoperative outcome after transthoracic esophagectomy? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2006;391:455-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Parina RP, Chang DC, Rose JA, Talamini MA. Is a low readmission rate indicative of a good hospital? J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:169-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Thomas JW, Holloway JJ. Investigating early readmission as an indicator for quality of care studies. Med Care. 1991;29:377-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Wick EC, Shore AD, Hirose K, Ibrahim AM, Gearhart SL, Efron J, Weiner JP, Makary MA. Readmission rates and cost following colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1475-1479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |