Published online May 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i18.4604

Peer-review started: January 21, 2016

First decision: February 18, 2016

Revised: March 2, 2016

Accepted: March 14, 2016

Article in press: March 14, 2016

Published online: May 14, 2016

Processing time: 105 Days and 10.9 Hours

Pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome associated with colorectal cancer is extremely rare. We report here a case of pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome secondary to metachronous ovarian metastases from colon cancer. A 65-year-old female with a history of surgery for transverse colon cancer and peritoneal dissemination suffered from metachronous ovarian metastases during treatment with systemic chemotherapy. At first, neither ascites nor pleural effusion was observed, but she later complained of progressive abdominal distention and dyspnea caused by rapidly increasing ascites and pleural effusion and rapidly enlarging ovarian metastases. Abdominocenteses were repeated, and cytological examinations of the fluids were all negative for malignant cells. We suspected pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome, and bilateral oophorectomies were performed after thorough informed consent. The patient’s postoperative condition improved rapidly after surgery. We conclude that pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome should be included in the differential diagnosis of massive or rapidly increasing ascites and pleural effusion associated with large or rapidly enlarging ovarian tumors.

Core tip: Pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome associated with colorectal cancer is extremely rare. Here, we report a case of this syndrome secondary to metachronous ovarian metastases from transverse colon cancer. This patient complained of progressive abdominal distention and dyspnea preoperatively, but her postoperative condition improved rapidly after bilateral oophorectomies. We conclude that pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome should be included in the differential diagnosis of massive or rapidly increasing ascites and pleural effusion associated with large or rapidly enlarging ovarian tumors.

- Citation: Kyo K, Maema A, Shirakawa M, Nakamura T, Koda K, Yokoyama H. Pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome secondary to metachronous ovarian metastases from transverse colon cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(18): 4604-4609

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i18/4604.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i18.4604

Meigs’ syndrome is defined by the presence of a benign ovarian tumor with ascites and pleural effusion that resolve after removal of the tumor[1]. The ovarian tumors in Meigs’ syndrome are fibromas or fibroma-like tumors, and other benign or malignant pelvic tumors associated with ascites and pleural effusion are described as pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome[2]. Pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome associated with colorectal cancer is extremely rare, and the etiology of ascites and pleural effusion in this syndrome remains unknown. We describe here a case of pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome secondary to metachronous ovarian metastases from transverse colon cancer and discuss the etiology of the ascites and pleural effusion in this syndrome.

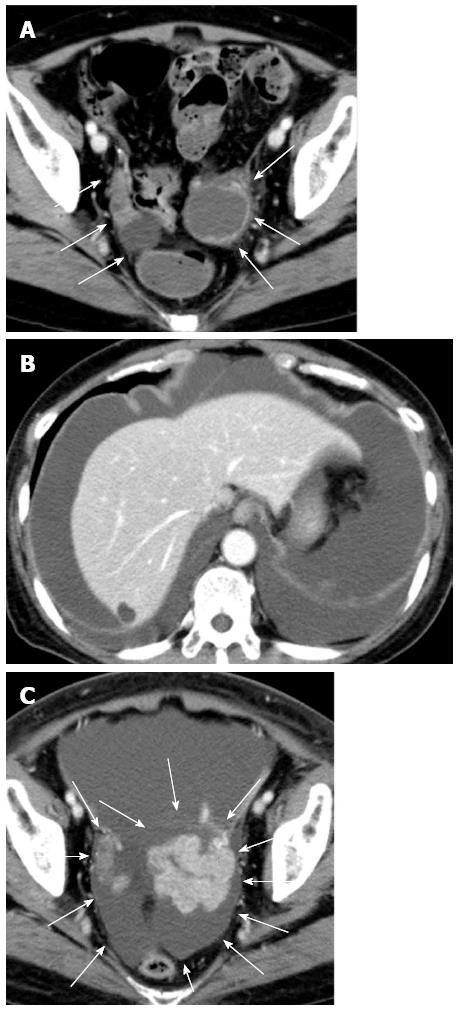

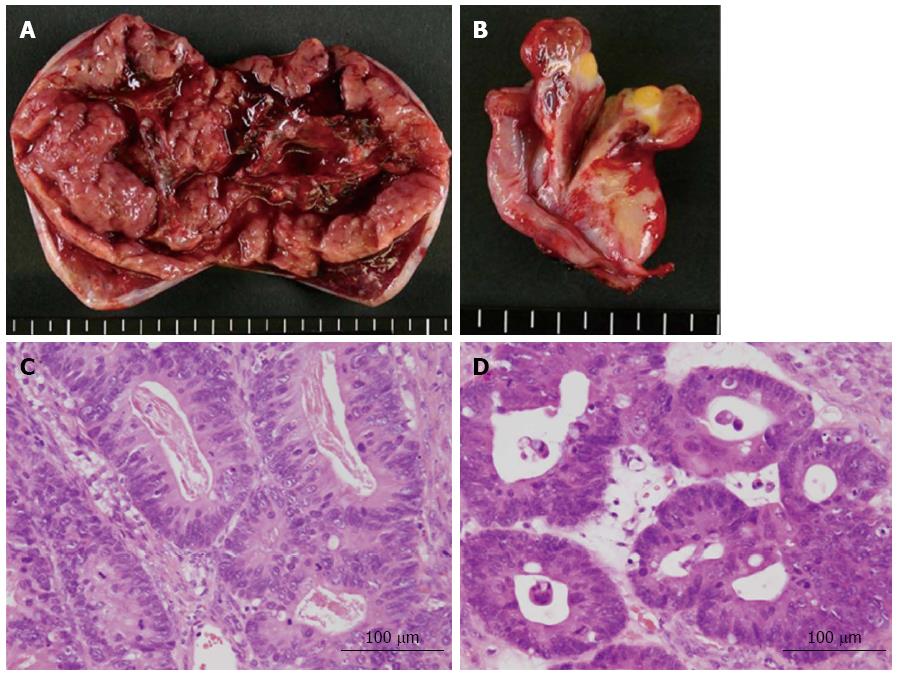

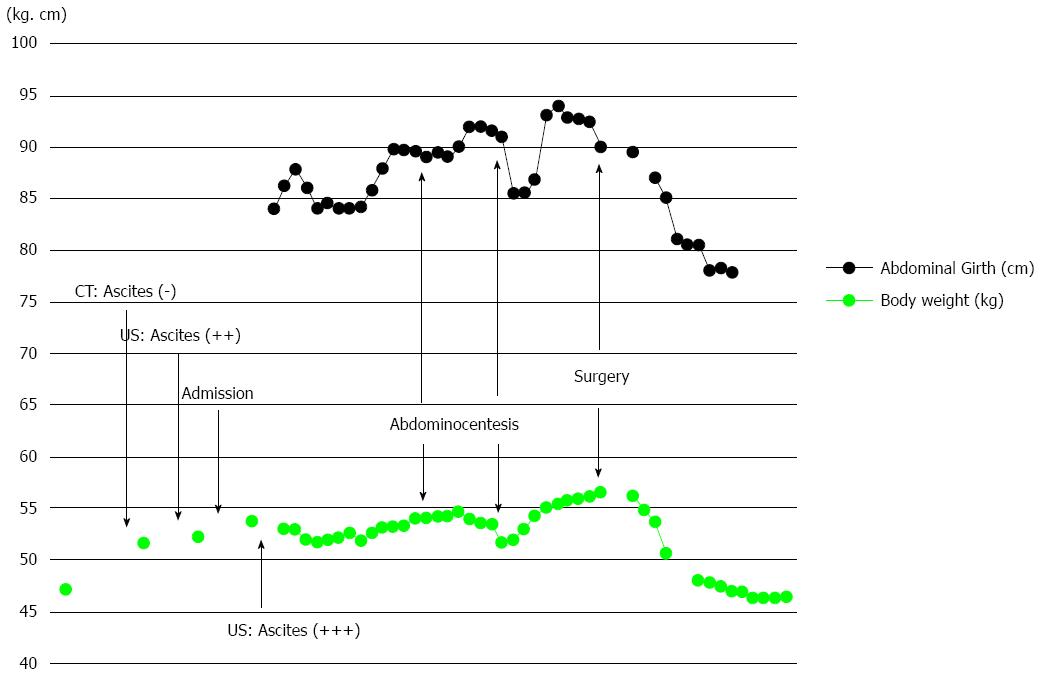

A 65-year-old female with a history of surgery for ileus due to transverse colon cancer was admitted to our department for the induction of oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy. During the previous surgery, we had found numerous nodules of peritoneal dissemination, each 1 mm in size under the right diaphragm and in the pelvis, as well as sparsely distributed nodules of similar size on the mesentery of the small intestine. Furthermore, a disseminated nodule 5 mm in size had been observed in the greater omentum. We had performed right hemicolectomy with ileocolic anastomosis and omentectomy. Pathologically, moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma had been observed in the colonic tumor and in the resected nodule in the omentum, and no lymph node metastasis had been observed. After 1 year and 3 mo of treatment with irinotecan-based chemotherapy, computed tomography (CT) examination performed 22 d before admission revealed bilateral enlarged ovaries with solid and cystic components, suggesting bilateral ovarian metastases (Figure 1A). Although neither ascites nor pleural effusion had been observed in the CT examination, the patient had already gained more than 4 kg, and a moderate amount of ascites had been identified by an abdominal ultrasound examination performed 9 d before admission. Four days after admission, she complained of abdominal distention and bilateral edema of the legs, and an abdominal ultrasound examination completed on the same day identified massive ascites and a small amount of bilateral pleural effusion. She soon became unable to eat because of abdominal distention. She also complained of progressive dyspnea, and at worst, her oxygen saturation was 88% in room air. CT examination performed 26 d after admission showed a large amount of ascites and pleural effusion with left-side predominance (Figure 1B and C). Bilateral ovarian tumors showed a rapid increase in size, and the left and right ovaries measured 97 mm × 66 mm and 80 mm × 29 mm, respectively (Figure 1B and C). Abdominocenteses were performed three times, and cytological examinations of the fluids were all negative for malignant cells. Despite the diffuse peritoneal dissemination observed during the previous surgery, we suspected pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome caused by metastatic ovarian tumors and recommended the patient for surgery. Laboratory tests prior to surgery showed carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels at 2.9 ng/mL (normal, < 5 ng/mL), carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 levels at 51.4 U/mL (normal, < 37 U/mL), and CA 125 levels at 1150.0 U/mL (normal, < 35 U/mL). After thorough informed consent, a laparotomy was performed by lower abdominal incision, and more than 3.6 L of serous fluid was removed. Bilateral oophorectomies were performed, and a drainage tube was inserted into the Douglas’ pouch. Although we could not inspect the right subphrenic region from the incision, we did not find any of the peritoneal nodules formerly observed on the mesentery of the small intestine and in the pelvis. The resected tumors from the left and right ovaries measured 90 mm × 55 mm and 30 mm × 30 mm, respectively (Figure 2A and B). Pathological examination revealed moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma of the ovaries that had negative immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin (CK) 7 but positive staining for CK18, CK19 and CK20, leading to the diagnosis of bilateral ovarian metastases from colon cancer (Figure 2C and D). The patient’s postoperative condition improved rapidly after surgery. The amount of fluid drained through the abdominal tube during postoperative day 1 was 150 mL, and the tube was removed 2 d after the surgery. Although the feeling of abdominal distention diminished soon after the surgery, both body weight and abdominal girth did not change for 3 d after the surgery but rapidly decreased thereafter (Figure 3). After hospital discharge, she was treated with chemotherapy, and a pulmonary metastasis was resected 1 year after the oophorectomies. Recurrence of peritoneal dissemination was suspected by CT examination 2 years and 4 mo after the oophorectomies, and jejuno-jejunal bypass was performed for jejunal obstruction 5 years and 2 mo after the oophorectomies. She died of cancer 6 years and 11 mo after the first operation and 5 years and 6 mo after the oophorectomies.

In 1937, Meigs and Cass[1] described 7 cases of ovarian fibromas associated with ascites and pleural effusion, and these manifestations were subsequently termed Meigs’ syndrome[3]. Pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome associated with colorectal cancers is extremely rare, and only 11 cases, including the present case, have been reported in the English literature (Table 1)[4-13]. Eight out of these 11 cases were reported in Japan, and most of the patients were under 60 years of age, which is younger than the mean age for the development of colorectal cancers in the general population. There seems to be no preponderance in the locations of the primary lesions, and the associated ovarian metastases were metachronous in only 3 cases, including this case. Because of the metachronous development of this syndrome, we could observe the patient in detail from its early phase.

| Ref. | Year | Age (yr) | Primary site | Onset of syndrome |

| Ryan[4] | 1972 | 35 | Transverse colon | Synchronous |

| Matsuzaki et al[5] | 1992 | 39 | Rectum | Synchronous |

| Nagakura et al[6] | 2000 | 53 | Sigmoid colon | Synchronous |

| Ohsawa et al[7] | 2003 | 41 | Sigmoid colon | Synchronous |

| Feldman et al[8] | 2004 | 49 | Cecum | Metachronous |

| Rubinstein et al[9] | 2009 | 61 | Cecum | Synchronous |

| Hosogi et al[10] | 2009 | 44 | Ascending colon | Synchronous |

| Okuchi et al[11] | 2010 | 42 | Rectum | Metachronous |

| Maeda et al[12] | 2011 | 58 | Sigmoid colon | Synchronous |

| Saito et al[13] | 2012 | 44 | Sigmoid colon | Synchronous |

| Present case | 2016 | 65 | Ascending colon | Metachronous |

The etiology of ascites in this syndrome is unclear, although several theories have been proposed. First, Meigs suggested that irritation of the peritoneal surface by a hard solid ovarian tumor could stimulate the production of peritoneal fluid[14]. A second theory is that ascites develops due to pressure on the superficial lymphatics of the tumor[3]. A third theory is that stromal edema and transudation may occur as a result of a discrepancy between the arterial supply to a large tumor and the venous and lymphatic drainage of the same mass[15]. A fourth theory suggests that excessive production of fluid by the peritoneum leads to ascites in this syndrome[16]. The last but probably the most plausible theory is that increased capillary permeability and the resultant third-space fluid shift occur due to increased levels of inflammatory cytokines and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)[17]. Abramov et al[17,18] reported high levels of interleukin (IL)-1beta, IL-6, IL-8, VEGF and fibroblast growth factor in serum, ascites and pleural effusion and a decline in serum levels of these inflammatory cytokines and vasoactive factors after removal of the ovarian tumor and suggested that the release of these factors from the tumor should be involved in the clinical manifestations of this syndrome by inducing capillary leakage and third-space fluid accumulation. The clinical manifestations of Meigs’ syndrome show great similarity with a severe form of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) that is associated with injection of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and is also characterized by massive cystic enlargement of the ovaries, ascites and pleural effusion[19]. In severe OHSS, ascites and pleural effusion develop due to increased capillary permeability and resultant third-space fluid shift, and VEGF produced from ovarian follicles under the prolonged effects of hCG is thought to play a key role[19,20]. The site of VEGF production in patients with pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome is currently unclear. Okuchi et al[11] reported that immunohistochemical staining examinations showed increased VEGF expression in oviduct epithelial cells of both metastatic and non-metastatic sides rather than in tumor cells. Given that increased capillary permeability and resultant third-space fluid shift form part of the etiology of ascites in this syndrome, this may explain why the body weight of the present patient had increased well before the emergence of ascites and why both body weight and abdominal girth did not change for 3 d after removal of the ovarian tumors and insertion of a drainage tube.

The etiology of pleural effusion also remains unclear, but the prevailing theory is that the transfer of ascites occurs through transdiaphragmatic lymphatics, which was demonstrated by the flow of intraperitoneally injected India ink from the peritoneum to the pleural cavity[21]. Terada et al[22] also demonstrated that labeled albumin injected into the peritoneum was detected in the right pleura in maximum concentration within 3 h. However, considering the similarity of this syndrome to severe OHSS, increased capillary permeability may also be involved in the etiology of pleural effusion.

While it may be difficult, it is very important to distinguish the clinical manifestations of pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome with those of disseminated malignant disease because in the case of this syndrome, removal of ovarian tumors will markedly improve not only the quality of life but also the prognosis of the patient. Thus, pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome should be included in the differential diagnosis of massive or rapidly increasing ascites and pleural effusion associated with large or rapidly enlarging ovarian tumors.

The patient was a 65-year-old female who had surgery for ileus caused by transverse colon cancer.

Pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis.

Laboratory tests before oophorectomies showed carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels at 2.9 ng/mL (normal, < 5 ng/mL), carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 levels at 51.4 U/mL (normal, < 37 U/mL), and CA 125 levels at 1150.0 U/mL (normal, < 35 U/mL).

Bilateral ovarian metastases with massive ascites and pleural effusion.

Moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma in the ovaries, compatible with metastases from transverse colon cancer.

Bilateral oophorectomies.

Pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome associated with colorectal cancer is extremely rare, and the etiology of ascites and pleural effusion in this syndrome remains unknown.

Meigs’ syndrome is defined by the presence of a benign ovarian tumor with ascites and pleural effusion that resolve after removal of the tumor. The ovarian tumors in Meigs’ syndrome are fibromas or fibroma-like tumors, and other benign or malignant pelvic tumors associated with ascites and pleural effusion are described as pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome.

This case report may provide supporting evidence for the etiology of ascites and pleural effusion in pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome; our observations that the body weight of the patient had increased well before the emergence of ascites and that both the body weight and abdominal girth did not change for 3 d after removal of the ovarian tumors support the idea that increased capillary permeability and the resultant third-space fluid shift explain the etiology of ascites and pleural effusion in this syndrome.

The authors conclude that pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome should be included in the differential diagnosis of massive or rapidly increasing ascites and pleural effusion associated with large or rapidly enlarging ovarian tumors.

P- Reviewer: Chow CFK, Rodrigo L S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Meigs JV, Cass JW. Fibroma of the ovary with ascites and hydrothorax: a report of seven cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1937;33:249-266. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Meigs JV. Pelvic tumors other than fibromas of the ovary with ascites and hydrothorax. Obstet Gynecol. 1954;3:471-486. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Rhoads JE, Terrell AW. Ovarian fibroma with ascites and hydrothorax (Meigs’ syndrome). JAMA. 1937;109:1684-1687. |

| 4. | Ryan RJ. PseudoMeigs syndrome. Associated with metastatic cancer of ovary. N Y State J Med. 1972;72:727-730. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Matsuzaki M, Murase M, Kamiya I, Horio S, Sakuma H. A case of Meigs’ syndrome resulting from rectal cancer (in Japanese with English abstract). J Jpn Soc Clin Surg. 1992;53:667-670. |

| 6. | Nagakura S, Shirai Y, Hatakeyama K. Pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome caused by secondary ovarian tumors from gastrointestinal cancer. A case report and review of the literature. Dig Surg. 2000;17:418-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ohsawa T, Ishida H, Nakada H, Inokuma S, Hashimoto D, Kuroda H, Itoyama S. Pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome caused by ovarian metastasis from colon cancer: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33:387-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Feldman ED, Hughes MS, Stratton P, Schrump DS, Alexander HR. Pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome secondary to isolated colorectal metastasis to ovary: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:248-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rubinstein Y, Dashkovsky I, Cozacov C, Hadary A, Zidan J. Pseudo meigs’ syndrome secondary to colorectal adenocarcinoma metastasis to the ovaries. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1334-1336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hosogi H, Nagayama S, Kanamoto N, Yoshizawa A, Suzuki T, Nakao K, Sakai Y. Biallelic APC inactivation was responsible for functional adrenocortical adenoma in familial adenomatous polyposis with novel germline mutation of the APC gene: report of a case. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39:837-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Okuchi Y, Nagayama S, Mori Y, Kawamura J, Matsumoto S, Nishimura T, Yoshizawa A, Sakai Y. VEGF hypersecretion as a plausible mechanism for pseudo-meigs’ syndrome in advanced colorectal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:476-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Maeda H, Okabayashi T, Hanazaki K, Kobayashi M. Clinical experience of Pseudo-Meigs’ Syndrome due to colon cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3263-3266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Saito H, Koide N, Miyagawa S. Pseudo-Meigs syndrome caused by sigmoid colon cancer metastasis to the ovary. Am J Surg. 2012;203:e1-e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Meigs JV. Fibroma of the ovary with ascites and hydrothorax; Meigs’ syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1954;67:962-985. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Samanth KK, Black WC. Benign ovarian stromal tumors associated with free peritoneal fluid. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970;107:538-545. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Lin JY, Angel C, Sickel JZ. Meigs syndrome with elevated serum CA 125. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:563-566. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Abramov Y, Anteby SO, Fasouliotis SJ, Barak V. The role of inflammatory cytokines in Meigs’ syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:917-919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Abramov Y, Anteby SO, Fasouliotis SJ, Barak V. Markedly elevated levels of vascular endothelial growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, and interleukin 6 in Meigs syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:354-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rizk B, Aboulghar M, Smitz J, Ron-El R. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukins in the pathogenesis of severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Hum Reprod Update. 1997;3:255-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | McClure N, Healy DL, Rogers PA, Sullivan J, Beaton L, Haning RV, Connolly DT, Robertson DM. Vascular endothelial growth factor as capillary permeability agent in ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Lancet. 1994;344:235-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lemming R. Meigs’ syndrome and pathogenesis of pleurisy and polyserositis. Acta Med Scand. 1960;168:197-204. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Terada S, Suzuki N, Uchide K, Akasofu K. Uterine leiomyoma associated with ascites and hydrothorax. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1992;33:54-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |