Published online Apr 28, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i16.4270

Peer-review started: October 26, 2015

First decision: November 13, 2015

Revised: December 10, 2015

Accepted: January 17, 2016

Article in press: January 18, 2016

Published online: April 28, 2016

Processing time: 176 Days and 16.7 Hours

Krukenberg tumor, a rare metastatic ovarian tumor arising from gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma mainly, tends to occur in premenopausal females. Finding the origin of a Krukenberg tumor is crucial for determining prognosis. In Eastern countries, the most common origin of Krukenberg tumor is stomach cancer, which is generally diagnosed via endoscopic biopsy to investigate an abnormal mucosal lesion. Here, we describe a case of huge adnexal mass in a 33-year-old woman who presented with abdominal distension. Two independent endoscopic examinations performed by experts in two tertiary university hospitals revealed no abnormal mucosal lesion. The patient was diagnosed with a Krukenberg tumor according to findings from random endoscopic biopsies taken from normal-looking gastric mucosa in our hospital. It is very rare to be diagnosed via a random biopsy in cases where three well-trained endoscopists had not found any mucosal lesion previously. Thus, in this case, random biopsy was helpful in finding the origin of a Krukenberg tumor.

Core tip: We describe a 33-year-old woman who was diagnosed with Krukenberg tumor of gastric origin after random biopsy taken during endoscopy for normal-looking mucosa. Although three well-trained endoscopists confirmed that there was no mucosal lesion in the stomach, the random biopsy from the corpus showed signet ring cell carcinoma. Clinical significance of this case is that clinicians should consider gastric malignancy for patients who have Krukenberg tumor of which the origin has not been found, even when the gastric mucosa appears to be intact. For these patients, random gastric biopsy may help to reveal the primary cancer.

- Citation: Lee SH, Lim KH, Song SY, Lee HY, Park SC, Kang CD, Lee SJ, Choi DW, Park SB, Ryu YJ. Occult gastric cancer with distant metastasis proven by random gastric biopsy. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(16): 4270-4274

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i16/4270.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i16.4270

Stomach cancer is the fourth most frequent malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide[1]. In South Korea, it is the second most common type of cancer and the third leading cause of cancer deaths[2]. A Krukenberg tumor is an ovarian metastatic carcinoma from a primary site, such as the gastrointestinal tract. Patients with this tumor type are generally between the ages of 40-years-old and 46-years-old, and present with variable symptoms. Because Krukenberg tumors are initially diagnosed at the highly advanced state, they have a poor prognosis; the median overall survival period has been reported as 7-14 mo[3]. In Asian countries, stomach cancer primary origin accounts for approximately 70% of the Krukenberg tumor cases[4-6], with this origin generally diagnosed via an endoscopic biopsy of an abnormal mucosal lesion. Although there has been a similar case report from Japan with identification during autopsy[7], the case we are reporting here is the first of Krukenberg tumor for which the primary origin was confirmed via random endoscopic biopsy. Herein, we report a case of Krukenberg tumor of gastric origin diagnosed via random endoscopic biopsy of apparently normal-looking gastric mucosa.

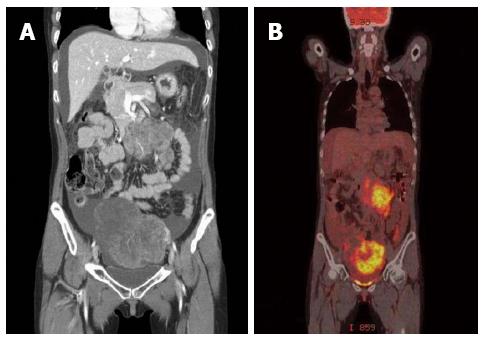

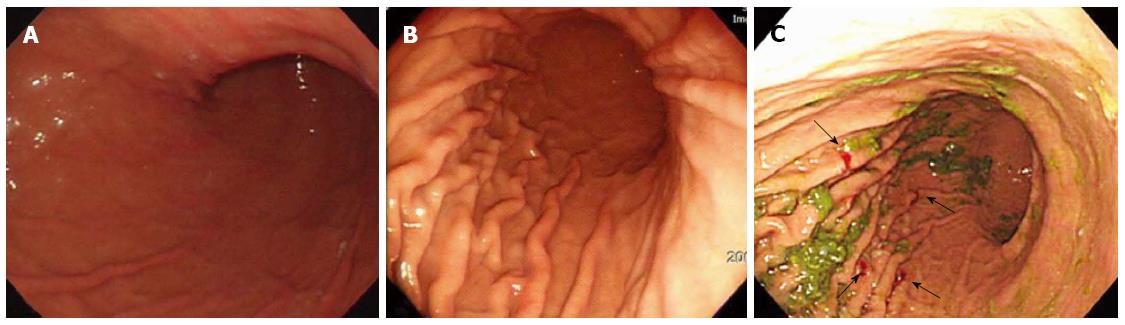

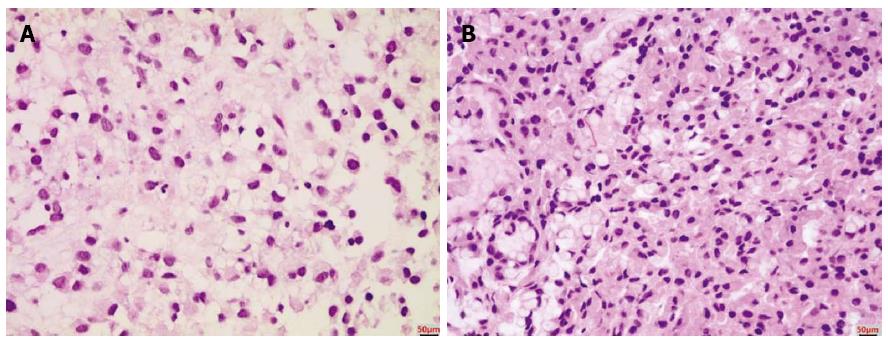

A 33-year-old woman with complaints of nausea and abdominal distension for 3 mo was admitted to a university hospital near her home. Examination by abdomino-pelvic computed tomography (CT) (Figure 1A) and positron emission tomography (PET)-CT (Figure 1B) revealed a left, huge ovarian mass and peritoneal metastatic lesions. To identify primary origins, gastroscopy and colonoscopy were performed, but showed no abnormal lesions (Figure 2A). Thereafter, she visited another tertiary university hospital for a second opinion; the diagnostic tests included repeat gastroscopy, which showed grossly normal mucosa similar to the previous findings (Figure 2B). A fine-needle biopsy was then conducted at the left supraclavicular lymph node (SCN), which yielded positive findings for signet ring cell carcinoma in the chest CT and the PET-CT (Figure 3A).

The patient was clinically diagnosed with Krukenberg tumor of an unknown primary origin. She was transferred to our hospital for supportive care, as she complained of severe pain and had poor oral intake. Upon physical examination, her abdomen was soft and distended, with a huge palpable mass in the lower abdomen. Anemia, leukocytosis, electrolyte imbalance, and high carbohydrate antigen (CA)125 level were found. Tests for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA19-9 markers were within normal ranges. Based on the clinical aspects and outside medical records that included radiologic imaging and histological findings for the left SCN, we considered the primary origin likely to be the upper digestive tract; thus, we decided to conduct random endoscopic gastric biopsy. It is important to note that the patient’s performance status contraindicated an invasive procedure, and consequently we did not perform any surgical procedures, such as staging laparoscopy. The endoscopic examination showed no abnormal mucosal lesion in the region from the cardia to the antrum, similar to the two previous endoscopic findings (Figure 2C). Random biopsies were taken from antrum (2 biopsies on the lesser curvature and 2 on the greater curvature) and body (1 biopsy on the lesser curvature and 4 on the greater curvature). The morphological finding of carcinoma was signet ring cell type adenocarcinoma, which was the same as that of the left SCN (Figure 3B). Immunohistochemical staining showed strong positivity for C-erbB2 (score of 3) and negativity for cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20. Therefore, the final diagnosis was Krukenberg tumor of gastric origin.

On the day 9 after the patient’s hospital admission, she underwent combination chemotherapy (trastuzumab, 5-FU, and cisplatin). However, the tumor had an aggressive course and the patient died of systemic fungal infection 2 mo later.

A Krukenberg tumor is considered a metastatic cancer of the ovary, usually from the gastrointestinal tract[8]. There are some differences between Asian and Western countries in the prevalence and primary origin of metastatic cancer of the ovary. In Europe, Krukenberg tumors reportedly account for 15% of all ovarian malignancies, with the primary sites of such cancers being gastrointestinal tract (39%), breast (28%), and endometrium (20%)[9]. On the other hand, Krukenberg tumor has been reported in 29% of cases of metastatic ovarian cancer in Japan, with the most common primary lesion being gastric cancer, with an incidence range of 69.6%-72.0%[5,6]. Similar prevalence of metastatic ovarian cancers has been reported for Korea; however, the most common primary origin is the stomach (66.7%), followed by the colon (17.6%) and the breast (5.6%)[4]. Al-Agha and Nicastri[10] reported that the prognosis of Krukenberg tumor was worse for cases in which the primary tumor was unidentified.

Krukenberg tumor often develops in premenopausal females[3,5,8]. Yang et al[11] reported that more than 80% of signet ring cell carcinomas are the absorptive and mucus-producing functional differentiation type (AMPFDT). Since AMPFDT expresses estrogen receptors, the proliferation and infiltration of signet ring cell carcinoma are affected by the estrogen level. Therefore, gastric signet ring cell carcinoma commonly metastasizes to the ovary or the uterine cervix, where the estrogen level is high[11]. Other possible pathways of metastasis of gastric cancer to the ovary are the lymphatic routes. Krukenberg tumor is an example of the selective spread of cancers, as is very common in the stomach-ovarian axis. Retrograde lymphatic spread is the most powerful candidate for the metastatic route for several reasons[10]. First, microscopic lymphatic permeation at the hilum and cortex has been observed in many cases. Second, there have been several reported cases of Krukenberg tumor with early gastric cancer that was limited to the mucosa and the submucosa, where a rich lymphatic plexus exists[12]. Lymphatic invasion can account for the spread of early gastric cancer. Third, some studies have demonstrated that greater number of metastatic lymph nodes is associated with higher risk of ovarian metastasis in gastric cancer[13].

Optimal treatment strategies for Krukenberg tumors have not been established yet. The role of surgical cytoreduction remains controversial; although, cytoreductive surgery combined with chemotherapy has been evidenced as an effective treatment of primary ovarian cancer[14]. A few studies have demonstrated surgery as capable of improving overall survival of patients with Krukenberg tumor of primary colorectal or breast cancer; on the contrary, patients with Krukenberg tumor from primary gastric cancer did not appear to benefit from cytoreductive surgery[14,15]. Therefore, treatment plans need to be individualized according to the type of primary cancer. The treatment for our patient, described herein, followed the standard guidelines for metastatic gastric cancer.

Prognosis of Krukenberg tumors is poorer than that of primary ovarian cancer. In addition, the overall survival of patients with Krukenberg tumor depends on the primary origin. Jiang et al[15] reported that the overall survival period of patients with Krukenberg tumor of gastric origin was about 12 mo, similar to that of patients with metastatic gastric cancer, whereas the overall survival periods of patients with Krukenberg tumor of the colon and other origins were 29.6 and 48.2 mo, respectively. Another study reported that the presence of peritoneal seeding was the only significant prognostic factor for Krukenberg tumor from gastric primary cancer[16].

At times, gastric cancers can be overlooked, even by expert gastroscopists. According to a Korean study, Bormann type 3 advanced gastric cancer (AGC) in the cardia of the stomach and Bormann type 4 AGC at the greater curvature were the most commonly overlooked types of gastric cancer[17]. Overlooking the lesions in the cardia was conjectured to be related to the technical difficulty of the endoscopic approach. In general, it is also considered difficult to find lesions in the side of the body with greater curvature, because they can be hidden by the gastric folds. In our case, there was little possibility of a lesion being overlooked, because three other endoscopists, who were sufficiently trained in a university hospital, had performed examination for abnormal mucosal lesions specifically; no area was found to be covered with the gastric folds during the endoscopy and the gastric contents were completely emptied in the two previous procedures. Besides, the patient did not show any gastric fold thickening with poor expansibility, which is one of the characteristic features of submucosal spreading AGC.

In conclusion, it is very important to know the origin of a Krukenberg tumor in order to plan the treatment strategy and determine prognosis. Unfortunately, about 10% of patients with Krukenberg tumor continue to have an unknown primary origin despite various efforts at identification. In such cases, multiple random gastric biopsies to further examine endoscopically normal-looking mucosa can be helpful, especially for Asian patients.

A 33-year-old woman with no significant medical history complained of a 3-mo history of nausea and abdominal distension.

The patient’s abdomen was soft and distended, with a huge palpable mass in the lower abdomen.

Primary ovarian cancer with metastasis, peritoneal carcinomatosis with ovary involvement.

Anemia, leukocytosis, electrolyte imbalance, and high carbohydrate antigen (CA) 125 level were shown.

Computed tomography showed a 13.2 cm × 9.1 cm heterogeneous enhancing mass in the left ovary and peritoneal infiltration, thickening, and ascites suggesting peritoneal seeding.

Signet ring cell type adenocarcinoma.

Combination chemotherapy (trastuzumab, 5-FU, and cisplatin).

Krukenberg tumor is considered a metastatic cancer. However, for some cases, primary cancer of the tumor may not be revealed. Outcomes can be different according to knowledge of the origin.

Recently, a new cell-functional classification of gastric carcinomas was proposed, and includes the absorptive and mucus-producing functional differentiation type (AMPFDT). Most of the signet ring cell type adenocarcinomas found in this case were AMPFDT.

In selected cases, multiple random gastric biopsies obtained from endoscopically normal-looking mucosa can aid in identifying the primary cancer of Krukenberg tumor.

It’s an interesting report regarding the application of random biopsy in detecting the primary origin site of the patient with a Krukenberg tumor.

P- Reviewer: Arigami T, Wang YH S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13286] [Cited by in RCA: 13558] [Article Influence: 677.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Oh CM, Lee DH, Lee JS. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2011. Cancer Res Treat. 2014;46:109-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McGill FM, Ritter DB, Rickard CS, Kaleya RN, Wadler S, Greston WM, O’Hanlan KA. Krukenberg tumors: can management be improved? Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1999;48:61-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kim YW, Lee HW, Kang JS. Clinical Analysis of Krukenberg Tumor -A Review of 18 Cases-. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 1991;34:1451-1456. |

| 5. | Yakushiji M, Tazaki T, Nishimura H, Kato T. Krukenberg tumors of the ovary: a clinicopathologic analysis of 112 cases. Nihon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai Zasshi. 1987;39:479-485. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Yada-Hashimoto N, Yamamoto T, Kamiura S, Seino H, Ohira H, Sawai K, Kimura T, Saji F. Metastatic ovarian tumors: a review of 64 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:314-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nakamura Y, Hiramatsu A, Koyama T, Oyama Y, Tanaka A, Honma K. A Krukenberg Tumor from an Occult Intramucosal Gastric Carcinoma Identified during an Autopsy. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2014;2014:797429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hale RW. Krukenberg tumor of the ovaries. A review of 81 records. Obstet Gynecol. 1968;32:221-225. [PubMed] |

| 9. | de Waal YR, Thomas CM, Oei AL, Sweep FC, Massuger LF. Secondary ovarian malignancies: frequency, origin, and characteristics. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:1160-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Al-Agha OM, Nicastri AD. An in-depth look at Krukenberg tumor: an overview. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1725-1730. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Yang XF, Yang L, Mao XY, Wu DY, Zhang SM, Xin Y. Pathobiological behavior and molecular mechanism of signet ring cell carcinoma and mucinous adenocarcinoma of the stomach: a comparative study. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:750-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kakushima N, Kamoshida T, Hirai S, Hotta S, Hirayama T, Yamada J, Ueda K, Sato M, Okumura M, Shimokama T. Early gastric cancer with Krukenberg tumor and review of cases of intramucosal gastric cancers with Krukenberg tumor. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1176-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim NK, Kim HK, Park BJ, Kim MS, Kim YI, Heo DS, Bang YJ. Risk factors for ovarian metastasis following curative resection of gastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 1999;85:1490-1499. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Kim WY, Kim TJ, Kim SE, Lee JW, Lee JH, Kim BG, Bae DS. The role of cytoreductive surgery for non-genital tract metastatic tumors to the ovaries. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;149:97-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jiang R, Tang J, Cheng X, Zang RY. Surgical treatment for patients with different origins of Krukenberg tumors: outcomes and prognostic factors. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:92-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yook JH, Oh ST, Kim BS. Clinical prognostic factors for ovarian metastasis in women with gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:955-959. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Sung IK, Kim YC, Yun JW, Seo HI, Park DI, Cho YK, Kim HJ, Park JH, Sohn CI, Jeon WK. Characteristics of advanced gastric cancer undetected on gastroscopy. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2011;57:288-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |