Published online Apr 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i14.3803

Peer-review started: November 10, 2015

First decision: November 27, 2015

Revised: December 13, 2015

Accepted: January 9, 2016

Article in press: January 11, 2016

Published online: April 14, 2016

Processing time: 140 Days and 17.7 Hours

AIM: To investigate the impact of high-dose hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) on hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) recurrence and overall survival after living donor liver transplantation (LDLT).

METHODS: We investigated 168 patients who underwent LDLT due to HCC, and who were HBV-DNA/hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) -positive, from January 2008 to December 2013. After assessing whether the patients met the Milan criteria, they were assigned to the low-dose HBIG group and high-dose HBIG group. Using the propensity score 1:1 matching method, 38 and 18 pairs were defined as adhering to and not adhering to the Milan criteria. For each pair, HCC recurrence, HBV recurrence and overall survival were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method and the log rank test according to the HBIG dose.

RESULTS: Among those who met the Milan criteria, the 6-mo, 1-year, and 3-year HCC recurrence-free survival rates were 88.9%, 83.2%, and 83.2% in the low-dose HBIG group and 97.2%, 97.2%, and 97.2% in the high-dose HBIG group, respectively (P = 0.042). In contrast, among those who did not meet the Milan criteria, HCC recurrence did not differ according to the HBIG dose (P = 0.937). Moreover, HBV recurrence and overall survival did not differ according to the HBIG dose among those who met (P = 0.317 and 0.190, respectively) and did not meet (P = 0.350 and 0.987, respectively) the Milan criteria.

CONCLUSION: High-dose HBIG therapy can reduce HCC recurrence in HBV-DNA/HBeAg-positive patients after LDLT.

Core tip: This is a single center analysis of the effects of high-dose hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) therapy on the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B in hepatitis B virus (HBV)-DNA/hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive patients after LDLT. High-dose HBIG therapy can be helpful in improving hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence-free survival in HBV-DNA/HBeAg-positive recipients who met the Milan criteria. In contrast, high-dose HBIG therapy was not effective in improving HCC recurrence-free survival in HBV-DNA/HBeAg-positive recipients who did not meet the Milan criteria. Recurrence of hepatitis B and overall survival were not affected by the HBIG dose in HBV-DNA/HBeAg-positive recipients regardless of the Milan status.

- Citation: Lee EC, Kim SH, Lee SD, Park H, Lee SA, Park SJ. High-dose hepatitis B immunoglobulin therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma with hepatitis B virus-DNA/hepatitis B e antigen-positive patients after living donor liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(14): 3803-3812

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i14/3803.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i14.3803

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of primary liver cancer. Approximately 700000 people are annually diagnosed with HCC worldwide. This condition usually develops in patients with cirrhosis, and is common in areas with a high prevalence of infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus, such as Africa and East Asia[1]. In South Korea, HCC is the fifth most common cancer, and the HBV is its most important risk factor for HCC, accounting for approximately 70% of all HCC cases[2]. Despite the available therapeutic treatment of HCC, such as liver transplantation and resection, tumor recurrence remains problematic. The HCC recurrence rate after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) reportedly ranges from 15% to 20%, whereas the survival rate among patients with recurrent HCC is reportedly 22% within 5 years[3-5].

The results of liver transplantation have markedly improved as a result of the rapid evolution of hepatitis B treatment strategies over the past decades. In 1991, Samuel et al[6] reported a HBV recurrence prevention rate of approximately 80% with hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) after liver transplantation. Since then, HBIG has become an important component of the prevention strategy for HBV. Despite the use of nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs) such as lamivudine that have a superior efficacy, an increase in the hepatitis B recurrence rate was observed due to the emergence of HBV-DNA mutants in the long-term follow-up[7]. Subsequently, combination prophylaxis with HBIG and NAs became the standard method for HBV after OLT.

It is well known that HBV induces HCC[8,9]. Some researchers have indicated that the viral replication status is a predictor of relapse after HCC surgery[10,11]. However, the relationship between the HBIG dose and HCC recurrence or overall survival rate after OLT has not yet been established. In the present study, we aimed to determine the effect of high-dose HBIG therapy on HCC recurrence, HBV recurrence, and overall survival in HBV-DNA/hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive patients after living donor liver transplantation (LDLT).

From January 2008 to December 2013, 168 patients with HCC who were HBV-DNA/HBeAg-positive underwent LDLT at the National Cancer Center in the Republic of Korea. Those who have extrahepatic metastasis or obvious cases of major vascular incidents, such as portal vein or hepatic veins, have been excluded from the research. Patients with any other types of cancers in addition to HCC, severe cardiopulmonary comorbidity, active drug or alcohol abuse or active septic infections have also been excluded. The clinicopathologic variables of such patients, including age, sex, Child-Pugh score, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level, tumor number, largest tumor size, Edmondson-Steiner grade, major vessel (major branch of the hepatic vein/portal vein) invasion, microvascular invasion, bile duct invasion, and satellite nodule were analyzed. This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

Prior to May 2011, HBIG was administered to patients with HCC who were HBV-DNA/HBeAg-positive before OLT, as follows: 10000 IU of HBIG (Green Cross Corp., Seoul, South Korea) was administered daily for the first week, after which it was administrated weekly for 1 mo. Thereafter, 10000 IU/L of HBIG was administered according to the serum hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) titer to maintain a titer of greater than 500 IU/L during the first year, and greater than 200 IU/L thereafter.

After May 2011, 20000 IU of HBIG was administered daily for the first week, after which it was administered weekly for the rest of the month. Thereafter, 20000 IU of HBIG was administered monthly for 1 year, followed by administrations at varying doses to maintain a serum anti-HBs titer of > 200 IU/L.

For patients who were taking an anti-viral agent before OLT, the same drug was administered. In other cases, entecavir (ETV) was administered following LDLT.

For induction therapy, 20 mg of basiliximab was administered on the operation day and on postoperative day 4. The immunosuppressive regimens consisted of a combination of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil and corticosteroids after high-dose steroid administration during the operation. The initial target levels of tacrolimus ranged from 8 to 12 ng/mL, and mycophenolate mofetil was started with a dose of 1.5 g/d. The corticosteroid doses were reduced until they were discontinued over 6 mo after LDLT.

In each patient, post-transplantation follow-up was initially performed weekly after hospital discharge, and was then conducted bi-weekly or monthly, as clinically indicated. Biochemical tests were performed for assessing liver function, AFP levels, HBsAg levels, and anti-HBs titers at each visit. The serum HBV-DNA titer was also monitored regularly in all the patients for 1 year after LDLT. Thereafter, the patients were followed up for recurrence approximately every 2 or 3 mo for 1 year, and every 6 mo for the next 3 years.

The definition of HBV recurrence was detectable HBsAg or HBV-DNA. HBsAg and HBeAg were measured via chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay. The quantitative measurement of HBV-DNA was performed as follows. From January to April 2008, the serum HBV-DNA titers were monitored using the antibody capture solution hybridization HBV-DNA quantitative assay (Digene Hybrid Capture II Assay; Digene Corp., Beltsville, Md., United States), which had a lower detection limit of 100000 copies/mL[12]. Between May 2008 and April 2011, the COBAS AMPLICOR HBV MONITOR test (Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, Calif., United States) was used, which had a lower detection limit of 2000 copies/mL[12]. After May 2011, the Abbott RealTime assays (Abbott Laboratories, Des Plaines, IL, United States) was used, which had a lower quantification limit of 70 copies/mL[13-16].

And imaging studies, including abdomen and chest computed tomography (CT), were also conducted every 3 or 6 mo. If HCC recurrence was suspected based on the results of these imaging tests, additional liver magnetic resonance imaging and positron-emission-tomographic-(PET)-CT imaging were performed. In case it was difficult to diagnose HCC recurrence through imaging tests, a biopsy was performed for confirmation.

The maximum follow-up period was 5 years, and the censored data were observed until April 2015. In HCC patients who met the Milan criteria, the median follow-up periods of the low- and high-dose groups were 55.5 mo (range, 0.6-60 mo) and 29.0 mo (range, 1.9-47.2 mo), respectively. In the HCC patients who did not meet the Milan criteria, the median follow-up periods of the low- and high-dose groups were 18.4 mo (range, 1.5-60 mo) and 11.4 mo (range, 1.7-41.2 mo), respectively.

The baseline clinicopathologic variables were analyzed using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test for the categorical variables, and the Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for the continuous variables, depending on the normality of the distribution. The patients were randomly matched into 1:1 pairs using calipers of width equal to 0.1 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score, without replacement. The following served as contributors to the propensity score: age, sex, Child-Pugh score, AFP level, tumor number, largest tumor size, Edmondson-Steiner grade, major vessel (major branch of the hepatic vein/portal vein) invasion, microvascular invasion, bile duct invasion, and satellite nodule[17-21].

Overall, 38 and 18 pairs were identified as adhering to the Milan criteria and not adhering to these criteria, respectively. The pairs were compared using the McNemar test for the binominal categorical variables, and the paired t-test or Wilcoxon signed rank test for the continuous variables, depending on the normality of the distribution.

HCC recurrence and overall survival were analyzed in accordance with the HBIG dose using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All calculations were made using the SPSS 22.0 statistical software package and R 2.15.2 (IBM, Inc., Chicago, IL). The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by the Biometric Research Branch, Research Institute and Hospital, National Cancer Center, Republic of Korea.

A total of 168 patients with HCC who were HBV-DNA/HBeAg-positive underwent LDLT at the National Cancer Center in the Republic of Korea between January 2008 and December 2013. Of these patients, 109 HCC patients met the Milan criteria, whereas 59 HCC patients did not meet the Milan criteria. Of the HCC patients who met the Milan criteria (n = 109), 62 were included in the low-dose HBIG group, whereas 47 were included in the high-dose HBIG group. Although a significant difference in the Child-Pugh score (P = 0.002) was observed between the groups, none of the other clinicopathologic factors showed significant differences. Of the HCC patients who did not meet the Milan criteria (n = 59), 33 were included in the low-dose HBIG group, whereas 26 were included in the high-dose HBIG group. Except for AFP (P = 0.049), none of the other variables showed significant differences between the groups (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Met the Milan criteria (n = 109) | Did not meet the Milan criteria (n = 59) | ||||

| Low-dose HBIG | High-dose HBIG | P value | Low-dose HBIG | High-dose HBIG | P value | |

| (n = 62) | (n = 47) | (n = 33) | (n = 26) | |||

| Age (yr) | 53.8 ± 6.4 | 53.6 ± 7.6 | 0.854 | 54.1 ± 7.4 | 53.0 ± 8.7 | 0.608 |

| Sex (male/female) | 49/13 | 35/12 | 0.575 | 30/3 | 21/5 | 0.284 |

| Child-Pugh score | 7 (5-13) | 5 (5-12) | 0.002 | 7 (5-13) | 6 (5-13) | 0.226 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 18.8 (2.0-8891.8) | 13.3 (1.8-3811.2) | 0.407 | 30.7 (3.5-31142.9) | 235.3 (2.9-57348.8) | 0.049 |

| Number of tumors | 1 (1-3) | 1 (1-3) | 0.857 | 1 (1-8) | 1 (1-5) | 0.743 |

| Largest tumor size (cm) | 2.2 (0.6-4.5) | 2.2 (0.8-4.0) | 0.504 | 5.4 (0.9-13.0) | 4.9 (1.1-25.0) | 0.976 |

| Edmond-Steiner grade (I,II/III,IV) | 26/36 | 21/26 | 0.774 | 8/25 | 2/24 | 0.161 |

| Major vessel invasion (absent/present) | 62/0 | 47/0 | N/A | 26/7 | 17/9 | 0.250 |

| Microvascular invasion (absent/present) | 42/17[3] | 30/17 | 0.420 | 11/22 | 6/20 | 0.388 |

| Bile duct invasion (absent/present) | 61/1 | 42/2 | 0.577 | 31/2 | 23/3 | 0.646 |

| Satellite nodule (absent/present) | 46/15[1] | 37/10 | 0.686 | 14/19 | 11/15 | 0.993 |

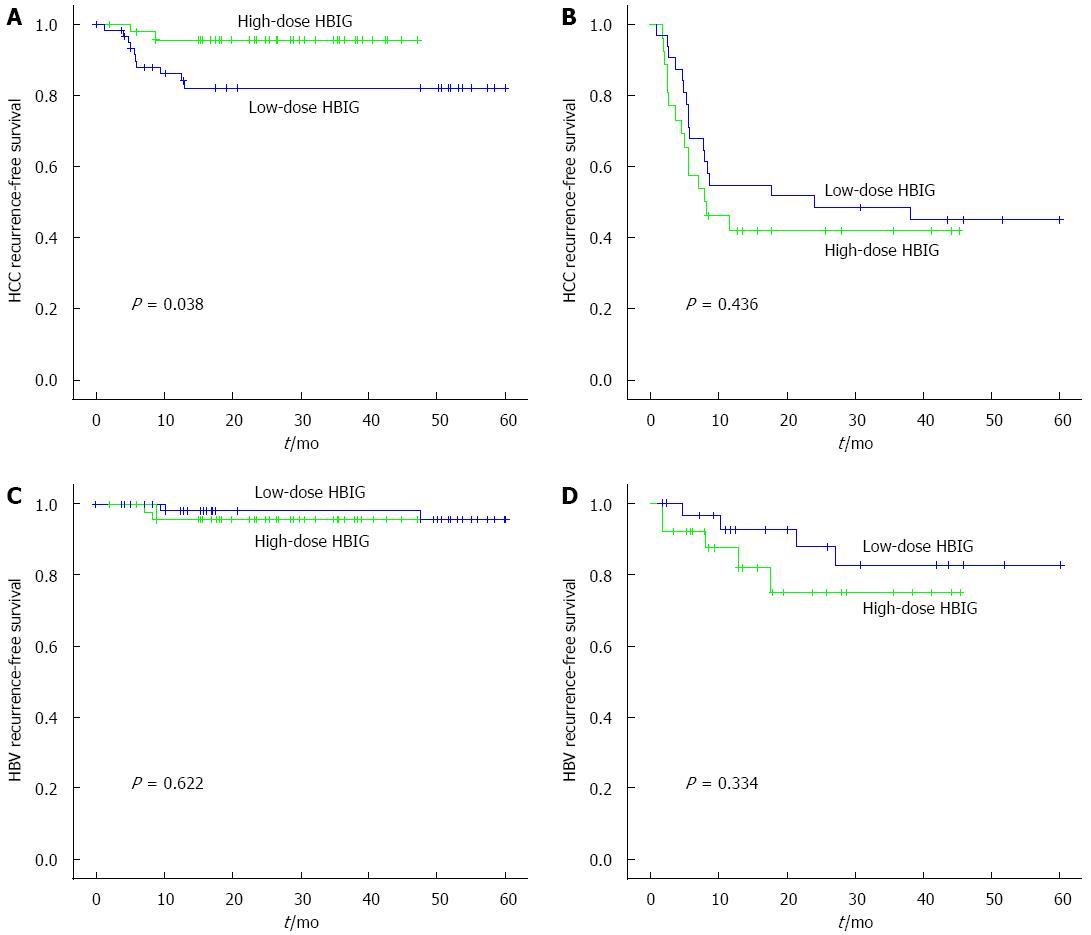

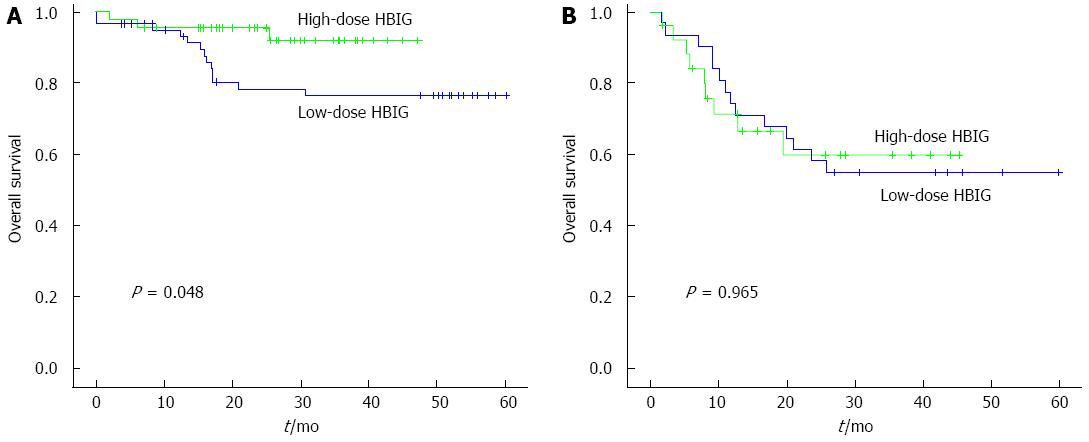

Among the HCC patients who met the Milan criteria (n = 109), the 6-mo, 1-year, and 3-year HCC recurrence-free survival rates in the low-dose HBIG group (n = 62) were 96.6%, 87.9%, and 82.2%, whereas those in the high-dose HBIG group (n = 47) were 95.6% for all (P = 0.038; Figure 1A). The 6-mo, 1-year, and 3-year HBV recurrence-free rates in the low-dose HBIG group (n = 62) were 100.0%, 98.1%, and 95.8%, whereas those in the high-dose HBIG group (n = 47) were 95.6% for all (P = 0.622; Figure 1C). The 6-mo, 1-year, and 3-year overall survival rates in the low-dose HBIG group (n = 62) were 96.8%, 91.4%, and 76.7%, whereas those in the high-dose HBIG group (n = 47) were 95.7%, 95.7%, and 92.1%, respectively (P = 0.048; Figure 2A).

Among the HCC patients who did not meet the Milan criteria (n = 59), the 6-mo, 1-year, and 3-year HCC recurrence-free survival rates in the low-dose HBIG group (n = 33) were 87.3%, 67.9%, and 45.0%, whereas those in the high-dose HBIG group (n = 26) were 76.9%, 53.8%, and 42.0%, respectively (P = 0.436; Figure 1B). The 6-mo, 1-year, and 3-year HBV recurrence-free survival rates in the low-dose HBIG group (n = 33) were 96.6%, 92.7%, and 82.6%, whereas those in the high-dose HBIG group (n = 26) were 92.3%, 82.0%, and 75.2%, respectively (P = 0.334; Figure 1D). No significant difference in overall survival was noted between the groups (P = 0.965; Figure 2B).

Using propensity matching, 38 pairs were found to have met the Milan criteria, whereas 18 pairs were found to have not met the Milan criteria. None of the variables in any of these pairs were found to significantly differ between the low- and high-dose HBIG groups (Table 2).

| Characteristic | Met the Milan criteria (38 pairs) | Did not meet the Milan criteria (18 pairs) | ||||

| Low-dose HBIG | High-dose HBIG | P value | Low-dose HBIG | High-dose HBIG | P value | |

| (n = 38) | (n = 38) | (n = 18) | (n = 18) | |||

| Age (yr) | 52.7 ± 5.5 | 53.4 ± 8.1 | 0.643 | 52.9 ± 8.0 | 53.3 ± 8.6 | 0.917 |

| Sex (male/female) | 32/6 | 29/9 | 0.453 | 16/2 | 16/2 | 1.000 |

| Child-Pugh score | 6 (5-12) | 6 (5-12) | 0.710 | 6 (5-13) | 6 (5-13) | 0.932 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 22.6 (2.0-8891.8) | 15.3 (1.8-3811.2) | 0.658 | 34.6 (3.5-31142.9) | 112.5 (2.9-57348.8) | 0.500 |

| Number of tumors | 1 (1-3) | 1 (1-3) | 0.963 | 1 (1-5) | 1 (1-5) | 0.811 |

| Largest tumor size (cm) | 2.2 (0.8-4.5) | 2.1 (0.8-4.0) | 0.994 | 5.75 (1.6-13.0) | 4.9 (1.1-25.0) | 0.393 |

| Edmond-Steiner grade (I, II/III, IV) | 17/21 | 17/21 | 1.000 | 4/14 | 2/16 | 0.500 |

| Major vessel invasion (absent/present) | 38/0 | 38/0 | N/A | 12/6 | 13/5 | 1.000 |

| Microvascular invasion (absent/present) | 23/15 | 26/12 | 0.664 | 5/13 | 4/14 | 1.000 |

| Bile duct invasion (absent/present) | 37/1 | 37/1 | 1.000 | 16/2 | 16/2 | 1.000 |

| Satellite nodule (absent/present) | 26/12 | 29/9 | 0.648 | 6/12 | 5/13 | 1.000 |

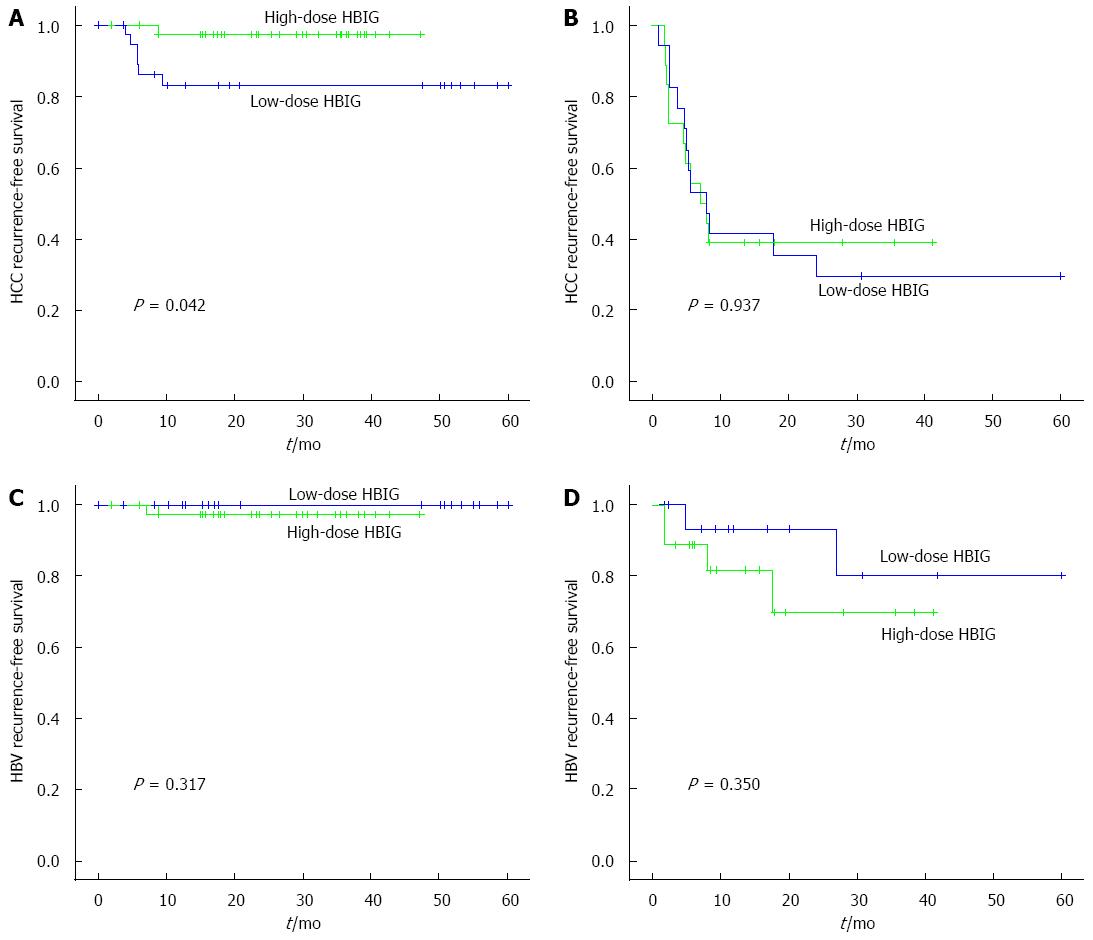

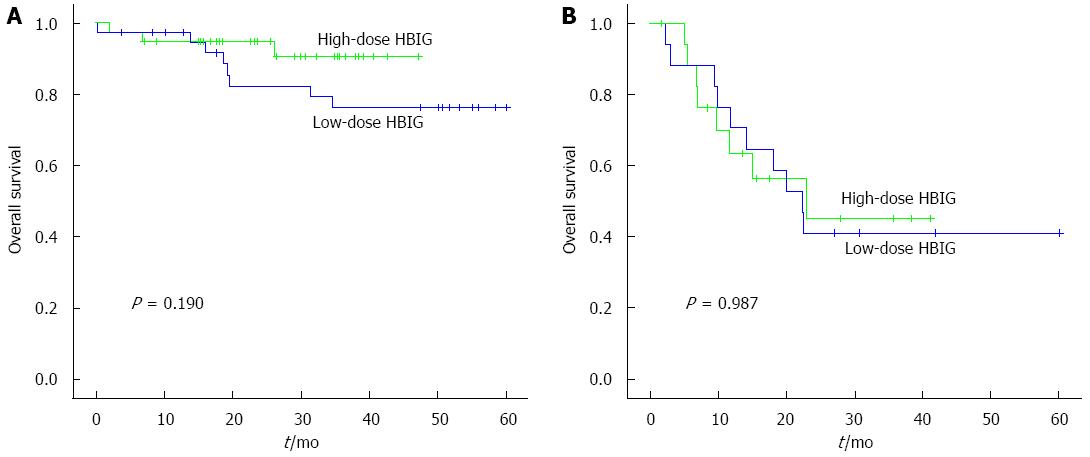

Among the patients who met the Milan criteria (n = 38), the 6-mo, 1-year, and 3-year HCC recurrence-free survival rates in the low-dose HBIG group (n = 38) were 88.9%, 83.2%, and 83.2%, whereas those in the high-dose HBIG group (n = 38) were 97.2%, 97.2%, and 97.2%, respectively (P = 0.042; Figure 3A). There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of HBV recurrence-free survival rates (P = 0.317; Figure 3C). The 6-mo, 1-year, and 3-year overall survival rates of the low-dose HBIG group (n = 38) were 94.4%, 79.3%, and 76.2%, whereas those in the high-dose HBIG group (n = 38) were 94.7%, 94.7%, and 90.6%, respectively (P = 0.190; Figure 4A).

Among the 18 pairs of patients who did not meet the Milan criteria, no significant differences in the HCC recurrence-free survival rates (P = 0.937; Figure 3B), HBV recurrence-free survival rates (P = 0.350; Figure 3D), and overall survival rate (P = 0.987; Figure 4B) were noted between the groups.

The presence of HBV-DNA in the serum is a reliable marker of active HBV replication, and the presence of HBeAg and the absence of the HBe antibody usually indicate active HBV replication and high infectiousness. Some studies indicated that the pre-OLT viral replicative status of the study subjects was a predictor of postoperative HCC recurrence[10,11]. Considering that HBV has been known to induce HCC[8,9,22], if the HBV recurrence rate decreased in the high-dose HBIG group, the reason for the HCC recurrence decrease might be clearly explained in our study. However, the outcome of the present study indicated that HBV recurrence did not significantly differ according to the HBIG dose among both HCC patients who met and did not meet the Milan criteria (P = 0.317 and 0.350, respectively).

Meanwhile, there were some reports that occult hepatitis B infection (OBI) could induce HCC[23-25]. OBI is defined as the presence of low levels of HBV-DNA in the serum, the cells of the lymphatic (immune) system, and/or the hepatic tissue in patients with serological markers of a previous infection [hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc)- and/or anti-HBs-positive] and without any serum HBsAg. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), which is a currently used HBV-DNA quantification method, has a lower quantification limit of 70 copies/mL[13-16]. In comparison, the previous-generation HBV-DNA quantification methods for measuring HBV-DNA, such as the hybrid capture assay and branched-DNA (bDNA) assay, have much lower sensitivity[12]. In other words, the HBV-DNA titer level was undetectable in the past, it is now enough to define it as OBI as the development of the HBV-DNA quantification methods. Accordingly, HCC recurrence may develop not only in the OBI cases but also in subclinical HBV infection cases wherein the HBV-DNA is undetectable at the present time, as only a small amount of material (e.g., the X protein of HBV[9,26,27]) produced by the virus may be needed to mediate or re-trigger the cancer. Therefore, in this study, HCC recurrence may have reduced as high-dose HBIG was more efficient for inhibiting the course induced by HBV, as compared to low-dose HBIG.

However, only minimal information is available on the manner in which HBIG protects the transplanted liver against HBV reinfection. Virus reproduction begins when the virion comes in contact with a suitable host cell. HBIG may protect naive hepatocytes against infection by the HBV virion by blocking a putative HBV receptor[28]. Alternatively, HBIG may neutralize the circulating virions through immune precipitation and immune complex formation, or may trigger an antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity response, resulting in target cell lysis[28,29]. Furthermore, HBIG has been reported to bind to hepatocytes and to interact with HBsAg within cells[30]. Regardless of the mechanism, clear evidence has been obtained for a dose-dependent response to HBIG treatment[31-33]. However, further studies may be required to clarify the several proposed mechanisms and to support the outcomes of this study.

Another interesting aspect was that no significant difference was observed in HCC recurrence according to the HBIG dose among the HCC patients who did not meet the Milan criteria (P = 0.937; Figure 3B). In these patients, HCC recurrence may have been caused by circulating tumor cells[34] instead of being mediated or promoted by HBV, as is frequently noted in the recurrence of cancer in other organs. This trend may be associated with the fact that the Milan criteria includes major vessel invasion, along with tumor size and number, as indications for OLT.

In this study, we did not observe any difference in the HBV recurrence according to the HBIG dose in those who met (P = 0.317; Figure 3C) and did not meet (P = 0.350; Figure 3D) the Milan criteria. Most of the patients were taking NAs before LDLT, whereas the other patients received ETV after LDLT. Combination therapy of low-dose HBIG and NAs is efficient and successful for preventing HBV recurrence after OLT, which has been proved several times[35-37]. As seen from our results, we believe that high-dose HBIG may not be essential for suppressing the HBV recurrence itself, but rather there may be a risk for HBsAg escape mutations, as reported in previous studies[38-41].

This study has certain limitations that are inherent to a non-randomized and retrospective study. Another limitation is that the effect of the pre-OLT HBV-DNA titer on patient matching was not sufficiently clarified. As reported in previous studies, the pre-OLT HBV-DNA titer is one of the risk factor for HCC and HBV recurrence after liver transplantation or liver resection[10,22,42]. In the present study, the effect of the pre-OLT HBV-DNA titer on group matching was not directly reflected as three different quantification methods were used during the study period, including the hybrid capture assay, HBV bDNA signal amplification assay, and RT-PCR. Among these methods, RT-PCR is the most sensitive, and has the lowest detection limit[12-14]. Accordingly, if the measurement were done via RT-PCR in the patients who were HBeAg- and hybrid-capture-assay- or bDNA-assay-negative, HBV-DNA-positive results might have been observed. However, RT-PCR was not used in our institution before May 2011.

The follow-up period of the high-dose HBIG group was shorter than that of the low-dose HBIG group. Among the patients who met the Milan criteria, the median follow-up periods of the low- and high-HBIG-dose groups were 55.5 mo (range, 0.6-60 mo) and 29.0 mo (range, 1.9-47.2 mo), respectively. Among those who did not meet the Milan criteria, the median follow-up periods of the low- and high-HBIG-dose groups were 18.4 mo (range, 1.5-60 mo) and 11.4 mo (range, 1.7-41.2 mo), respectively. High-dose HBIG was administered to the HCC patients with HBV-DNA/HBeAg-positive since May 2011; hence, the follow-up period of the high-dose HBIG group might not be sufficient to completely support the findings of this study.

In conclusion, high-dose HBIG therapy was confirmed to reduce HCC recurrence in patients who met the Milan criteria and who were HBV-DNA/HBeAg-positive after LDLT; to our knowledge, this is the first time such a finding has been reported. However, further prospective studies are required to confirm these results, and the optimal dose of HBIG therapy after LDLT should be reconsidered.

In Asia, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common cancer. The hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is endemic in most parts of Asia and chronic HBV infection was classified as group 1 carcinogens of HCC by the World Health Organization. The major prognostic factors in HBV-related HCC patients after orthotropic liver transplantation (OLT) are HBV and HCC recurrence.

For HBV prophylaxis following OLT, combination therapy of hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) and nucleos(t)ide analogues were used in most centers. In HCC patients who showed high infectiousness with HBV-DNA/ hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) -positive, a protocol that applies a higher dose of HBIG after OLT is commonly used for HBV prophylaxis. However, no previous studies regarding the effect of HBIG doses on HCC recurrence and overall survival in patients with high infectiousness after OLT was reported.

The results showed that high-dose HBIG therapy can improve HCC recurrence-free survival of patients with HCC who were HBV-DNA/HBeAg-positive after OLT.

Authors suggest that high-dose HBIG can be effective therapy in HCC with HBV-DNA/HBeAg-positive patients after OLT.

HBIG is a sterile solution of purified gamma globulin containing anti-HBs. It is prepared from plasma donated by healthy, screened donors with high titers of anti-HBs. It is used to prevent hepatitis B from occurring again in hepatitis B surface antigen-positive patients who have had OLT.

The strength of this study is that it is the first study regarding the effect of HBIG doses on HCC recurrence and overall survival in patients with high infectiousness after OLT. They conclude that a high-dose HBIG reduce HCC recurrence in patients with HCC who were HBV-DNA/HBeAg-positive after OLT. The paper is well written and of highly clinical implications.

P- Reviewer: Kin T, Taheri S S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2557-2576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3846] [Cited by in RCA: 4265] [Article Influence: 236.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Song IH, Kim KS. Current status of liver diseases in Korea: hepatocellular carcinoma. Korean J Hepatol. 2009;15 Suppl 6:S50-S59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Roayaie S, Schwartz JD, Sung MW, Emre SH, Miller CM, Gondolesi GE, Krieger NR, Schwartz ME. Recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplant: patterns and prognosis. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:534-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 346] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Regalia E, Fassati LR, Valente U, Pulvirenti A, Damilano I, Dardano G, Montalto F, Coppa J, Mazzaferro V. Pattern and management of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1998;5:29-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Welker MW, Bechstein WO, Zeuzem S, Trojan J. Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation - an emerging clinical challenge. Transpl Int. 2013;26:109-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Samuel D, Bismuth A, Mathieu D, Arulnaden JL, Reynes M, Benhamou JP, Brechot C, Bismuth H. Passive immunoprophylaxis after liver transplantation in HBsAg-positive patients. Lancet. 1991;337:813-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 322] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Perrillo R, Rakela J, Dienstag J, Levy G, Martin P, Wright T, Caldwell S, Schiff E, Gish R, Villeneuve JP. Multicenter study of lamivudine therapy for hepatitis B after liver transplantation. Lamivudine Transplant Group. Hepatology. 1999;29:1581-1586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Beasley RP, Hwang LY, Lin CC, Chien CS. Hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B virus. A prospective study of 22 707 men in Taiwan. Lancet. 1981;2:1129-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1838] [Cited by in RCA: 1758] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kew MC. Hepatitis viruses and hepatocellular carcinoma. Res Virol. 1998;149:257-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hung IF, Poon RT, Lai CL, Fung J, Fan ST, Yuen MF. Recurrence of hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with high viral load at the time of resection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1663-1673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wu JC, Huang YH, Chau GY, Su CW, Lai CR, Lee PC, Huo TI, Sheen IJ, Lee SD, Lui WY. Risk factors for early and late recurrence in hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2009;51:890-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ho SK, Chan TM, Cheng IK, Lai KN. Comparison of the second-generation digene hybrid capture assay with the branched-DNA assay for measurement of hepatitis B virus DNA in serum. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2461-2465. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Allice T, Cerutti F, Pittaluga F, Varetto S, Gabella S, Marzano A, Franchello A, Colucci G, Ghisetti V. COBAS AmpliPrep-COBAS TaqMan hepatitis B virus (HBV) test: a novel automated real-time PCR assay for quantification of HBV DNA in plasma. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:828-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Daniel HD, Fletcher JG, Chandy GM, Abraham P. Quantitation of hepatitis B virus DNA in plasma using a sensitive cost-effective “in-house” real-time PCR assay. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27:111-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ciotti M, Marcuccilli F, Guenci T, Prignano MG, Perno CF. Evaluation of the Abbott RealTime HBV DNA assay and comparison to the Cobas AmpliPrep/Cobas TaqMan 48 assay in monitoring patients with chronic cases of hepatitis B. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1517-1519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Thibault V, Pichoud C, Mullen C, Rhoads J, Smith JB, Bitbol A, Thamm S, Zoulim F. Characterization of a new sensitive PCR assay for quantification of viral DNA isolated from patients with hepatitis B virus infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3948-3953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schlitt HJ, Neipp M, Weimann A, Oldhafer KJ, Schmoll E, Boeker K, Nashan B, Kubicka S, Maschek H, Tusch G. Recurrence patterns of hepatocellular and fibrolamellar carcinoma after liver transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:324-331. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Steinmüller T, Seehofer D, Rayes N, Müller AR, Settmacher U, Jonas S, Neuhaus R, Berg T, Hopf U, Neuhaus P. Increasing applicability of liver transplantation for patients with hepatitis B-related liver disease. Hepatology. 2002;35:1528-1535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ben-Ari Z, Daudi N, Klein A, Sulkes J, Papo O, Mor E, Samra Z, Gadba R, Shouval D, Tur-Kaspa R. Genotypic and phenotypic resistance: longitudinal and sequential analysis of hepatitis B virus polymerase mutations in patients with lamivudine resistance after liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:151-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yi NJ, Suh KS, Cho JY, Kwon CH, Lee KW, Joh JW, Lee SK, Kim SI, Lee KU. Recurrence of hepatitis B is associated with cumulative corticosteroid dose and chemotherapy against hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:451-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Faria LC, Gigou M, Roque-Afonso AM, Sebagh M, Roche B, Fallot G, Ferrari TC, Guettier C, Dussaix E, Castaing D. Hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with an increased risk of hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1890-189; quiz 2155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yasunaka T, Takaki A, Yagi T, Iwasaki Y, Sadamori H, Koike K, Hirohata S, Tatsukawa M, Kawai D, Shiraha H. Serum hepatitis B virus DNA before liver transplantation correlates with HBV reinfection rate even under successful low-dose hepatitis B immunoglobulin prophylaxis. Hepatol Int. 2011;5:918-926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zobeiri M. Occult hepatitis B: clinical viewpoint and management. Hepat Res Treat. 2013;2013:259148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hollinger FB, Sood G. Occult hepatitis B virus infection: a covert operation. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ghisetti V, Marzano A, Zamboni F, Barbui A, Franchello A, Gaia S, Marchiaro G, Salizzoni M, Rizzetto M. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in HBsAg negative patients undergoing liver transplantation: clinical significance. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:356-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yang HI, Lu SN, Liaw YF, You SL, Sun CA, Wang LY, Hsiao CK, Chen PJ, Chen DS, Chen CJ. Hepatitis B e antigen and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:168-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 924] [Cited by in RCA: 915] [Article Influence: 39.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Murakami Y, Saigo K, Takashima H, Minami M, Okanoue T, Bréchot C, Paterlini-Bréchot P. Large scaled analysis of hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA integration in HBV related hepatocellular carcinomas. Gut. 2005;54:1162-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Shouval D, Samuel D. Hepatitis B immune globulin to prevent hepatitis B virus graft reinfection following liver transplantation: a concise review. Hepatology. 2000;32:1189-1195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sawyer RG, McGory RW, Gaffey MJ, McCullough CC, Shephard BL, Houlgrave CW, Ryan TS, Kuhns M, McNamara A, Caldwell SH. Improved clinical outcomes with liver transplantation for hepatitis B-induced chronic liver failure using passive immunization. Ann Surg. 1998;227:841-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Schilling R, Ijaz S, Davidoff M, Lee JY, Locarnini S, Williams R, Naoumov NV. Endocytosis of hepatitis B immune globulin into hepatocytes inhibits the secretion of hepatitis B virus surface antigen and virions. J Virol. 2003;77:8882-8892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Samuel D, Muller R, Alexander G, Fassati L, Ducot B, Benhamou JP, Bismuth H. Liver transplantation in European patients with the hepatitis B surface antigen. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1842-1847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 837] [Cited by in RCA: 746] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Beasley RP, Hwang LY, Stevens CE, Lin CC, Hsieh FJ, Wang KY, Sun TS, Szmuness W. Efficacy of hepatitis B immune globulin for prevention of perinatal transmission of the hepatitis B virus carrier state: final report of a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Hepatology. 1983;3:135-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products. Core SPC for human plasma derived hepatitis-B immunoglobulin for intravenous use (CPMP/BPWG/4027/02). London, UK: The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products 2003; . |

| 34. | Gupta GP, Massagué J. Cancer metastasis: building a framework. Cell. 2006;127:679-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2932] [Cited by in RCA: 3208] [Article Influence: 168.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Takaki A, Yagi T, Yamamoto K. Safe and cost-effective control of post-transplantation recurrence of hepatitis B. Hepatol Res. 2015;45:38-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lo CM, Fan ST, Liu CL, Lai CL, Wong J. Prophylaxis and treatment of recurrent hepatitis B after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;75:S41-S44. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Lok AS. Prevention of recurrent hepatitis B post-liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:S67-S73. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Cooreman MP, Leroux-Roels G, Paulij WP. Vaccine- and hepatitis B immune globulin-induced escape mutations of hepatitis B virus surface antigen. J Biomed Sci. 2001;8:237-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sheldon J, Soriano V. Hepatitis B virus escape mutants induced by antiviral therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:766-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ijaz S, Torre F, Tedder RS, Williams R, Naoumov NV. Novel immunoassay for the detection of hepatitis B surface ‘escape’ mutants and its application in liver transplant recipients. J Med Virol. 2001;63:210-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Protzer-Knolle U, Naumann U, Bartenschlager R, Berg T, Hopf U, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH, Neuhaus P, Gerken G. Hepatitis B virus with antigenically altered hepatitis B surface antigen is selected by high-dose hepatitis B immune globulin after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1998;27:254-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Saab S, Yeganeh M, Nguyen K, Durazo F, Han S, Yersiz H, Farmer DG, Goldstein LI, Tong MJ, Busuttil RW. Recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B reinfection in hepatitis B surface antigen-positive patients after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:1525-1534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |