Published online Apr 7, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i13.3670

Peer-review started: December 8, 2015

First decision: January 13, 2016

Revised: January 25, 2016

Accepted: February 22, 2016

Article in press: February 22, 2016

Published online: April 7, 2016

Processing time: 111 Days and 21.8 Hours

AIM: To assess the predictive value of Operative Link on Gastritis Assessment (OLGA) and Operative Link on Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Assessment (OLGIM) stages in gastric cancer.

METHODS: A prospective study was conducted with 71 patients with early gastric cancer (EGC) and 156 patients with non-EGC. All patients underwent endoscopic examination and systematic biopsy. Outcome measures were assessed and compared, including the Japanese endoscopic gastric atrophy (EGA) classification method and the modified OLGA method as well as the modified OLGIM method. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) status was determined for all study participants. Stepwise logistic regression modeling was performed to analyze correlations between EGC and the EGA, OLGA and OLGIM methods.

RESULTS: For patients with EGC and patients with non-EGC, the proportions of moderate-to-severe EGA cases were 64.8% and 44.9%, respectively (P = 0.005), the proportions of OLGA stages III-IV cases were 52.1% and 22.4%, respectively (P < 0.001), and the proportions of OLGIM stages III-IV cases were 42.3% and 19.9%, respectively (P < 0.001). OLGA stage and OLGIM stage were significantly related to EGA classification; specifically, logistic regression modeling showed significant correlations between EGC and moderate-to-severe EGA (OR = 1.95, 95% CI: 1.06-3.58, P = 0.031) and OLGA stages III-IV (OR = 3.14, 95%CI: 1.71-5.81, P < 0.001), but no significant correlation between EGC and OLGIM stages III-IV (P = 0.781). H. pylori infection rate was significantly higher in patients with moderate-to-severe EGA (75.0% vs 54.1%, P = 0.001) or OLGA/OLGIM stages III-IV (OLGA: 83.6% vs 55.8%, P < 0.001; OLGIM: 83.6% vs 57.8%, P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION: OLGA classification is optimal for EGC screening. A surveillance program including OLGA stage and H. pylori infection status may facilitate early detection of gastric cancer.

Core tip: Japanese endoscopic gastric atrophy classification, Operative Link on Gastritis Assessment (OLGA), and Operative Link on Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Assessment (OLGIM) have been proven separately as effective methods to evaluate severity of gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia. However, these methods have not been compared for prognosticating neoplastic development. This study compared the correlations of these three methods with early gastric cancer (EGC) and found that OLGA classification is optimal for EGC screening. A surveillance program based on OLGA stage and Helicobacter pylori infection status may represent a practical approach for detecting gastric cancer at an early stage.

- Citation: Zhou Y, Li HY, Zhang JJ, Chen XY, Ge ZZ, Li XB. Operative link on gastritis assessment stage is an appropriate predictor of early gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(13): 3670-3678

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i13/3670.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i13.3670

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide[1]. The prognosis of GC is meaningfully associated with tumor stage, as highlighted by the 5-year overall survival rate of patients with early gastric cancer (EGC) exceeding 90%[2,3]. The presence of atrophic gastritis (defined as loss of appropriate gland function), intestinal metaplasia (defined as replacement of gastric epithelium by intestinal-type epithelium, IM) and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection are well-known risk factors of GC. As atrophic gastritis and IM progress to GC in only a small proportion of patients[4], identifying the characteristics of the background mucosa in EGC may help clinicians to select a subgroup of patients who may benefit from a surveillance program.

In recent years, the Operative Link on Gastritis Assessment (OLGA), which is based on the histopathology findings of biopsy specimens, was proposed as an effective method to rank gastritis into stages with corresponding carcinoma risks[5,6]. It has been reported that a high-risk stage (defined as stage III or IV of the OLGA classification) is strongly correlated with a high risk of GC[7,8]. However, in consideration of the low interobserver agreement of OLGA classification, the Operative Link on Intestinal Metaplasia Assessment (OLGIM) was developed as an alternative, and was subsequently recommended as an effective method to predict GC risk due to its higher interobserver agreement and strong association with the OLGA stage[9,10].

The endoscopic gastric atrophy (EGA) assessment that uses Kimura-Takemoto classification was first applied in a study of Japanese subjects to evaluate the extent of endoscopic atrophic border (EAB) and the severity of gastric atrophy[11]. A subsequent study showed that moderate-to-severe grade of EGA was closely associated with an increased risk of GC[12]. EGA is regarded as an assessment of endoscopic gastric atrophy, in contrast to the OLGA and OLGIM methods which are identified as the assessments of histologic atrophy and IM. While all three methods have proven effective in assessing gastric atrophy and predicting the development of GC, their use remains limited and has not extended worldwide. The OLGA and OLGIM classifications are applied primarily in Europe and America; on the other hand, the EGA assessment is applied primarily in Japan and Vietnam. None of these three evaluation methods has been widely applied in China and other Asian countries, despite the fact that they harbor a high prevalence of GC.

Determining the optimal assessment method for predicting EGC makes sense for both patient care and allocation of medical resources. To the best of our knowledge, no research study to date has reported a comparative analysis of the associations between the three evaluation methods and EGC; as such, the relationship between EGA assessment and the OLGA/OLGIM stages remains unclear. We designed this prospective study to evaluate the characteristics of the background mucosa of EGC using three criterions, ultimately to investigate whether the EGA, OLGA or OLGIM method has the highest correlation with EGC so that the optimal means of assessment can be used in development of an appropriate surveillance program for detecting EGC in China.

The study was conducted prospectively at Shanghai Ren Ji Hospital from May 2013 to July 2015. Consecutive patients, ranging in age from 40 to 80 years, with diagnosis of functional dyspepsia or suspicion of EGC and who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy were recruited to the study. Patients were excluded from study participation based upon diagnosis of advanced GC, order or receipt of post-subtotal gastrectomy, or presence of any conditions that may interfere with clinical examination or treatment, such as acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding and severe systemic diseases (e.g., a severe cardiac condition, serious infection, or renal failure). Patients who lacked histology data were also excluded.

The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee, and all patients provided written informed consent. Patients were selected and classified into two groups. Patients with a pathological diagnosis of EGC or high-grade neoplasia (HGN) (categories 4-5 according to the revised Vienna classification)[13] were defined as the EGC group. Patients with a pathological diagnosis of non-gastritis, gastritis or low-grade neoplasia (LGN) (revised Vienna category 1-3) were defined as the non-EGC group.

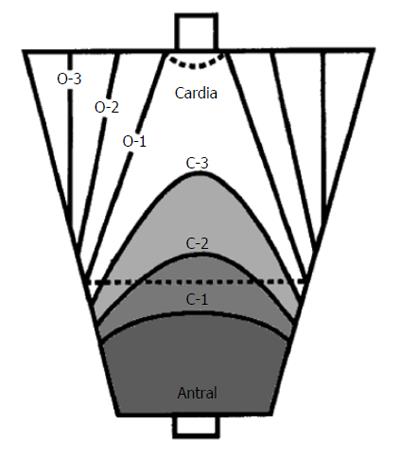

All patients were examined by a single experienced endoscopist, using a conventional endoscope (GIF-H260; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan), a magnifying endoscope (GIF-H260 Z; Olympus Medical Systems), and an electric endoscopic system (EVIS 260 Spectrum; Olympus Medical Systems). All patients were originally diagnosed using the Kimura-Takemoto EGA assessment[11] (Figure 1). The extent of atrophic gastritis was categorized according to the following two primary patterns: closed-type gastritis (C-type) and open-type gastritis (O-type). For the C-type, C1 sub-categorization represented highly localized antral gastritis, C2 sub-categorization represented increasing extension through the lesser curvature, and C3 sub-categorization represented increasing extension through the greater curvature. For the O-type, in which the gastritis reached the cardia, O1 sub-categorization indicated reaching the lesser curvature, O2 sub-categorization indicated reaching half of the stomach, and O3 sub-categorization indicated extensive atrophic gastritis that affected almost the entire stomach. According to the patient’s EGA classification, the endoscopic atrophic pattern was divided into the following three degrees: mild (C1-C2), moderate (C3-O1) and severe (O2-O3). Then, biopsy samples (n) were obtained for histology from the following standardized sites: antrum (n = 3, including 1 for exclusive use in the rapid urease test (RUT) (Pronto Dry; Medical Instruments Corporation, Solothurn, Switzerland) and corpus (n = 2, including 1 from the lesser curvature and 1 from the greater curvature). If a suspicious lesion was found, 2-3 extra biopsy samples were obtained from the lesion.

Patients with suspected EGC or with a diagnosis of intraepithelial neoplasia by pathology were examined by magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (ME-NBI). The treatment for each patient was determined according to results from conventional endoscopy (CE) and ME-NBI, as well as biopsy pathologic diagnoses. When the biopsy pathology turned out to be gastritis or LGN (revised Vienna categories 1-3), the patients received follow-up. For those diagnosed with HGN and GC (revised Vienna categories 4-5) by biopsy pathology, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) or surgery were chosen according to the indications of endoscopic resection (ER)[13].

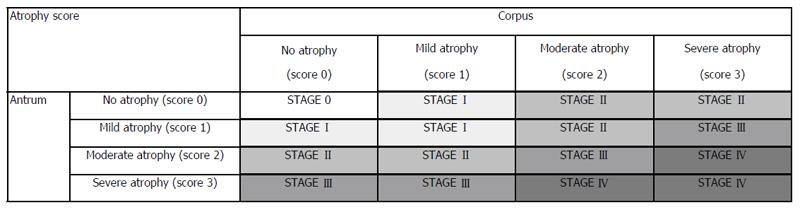

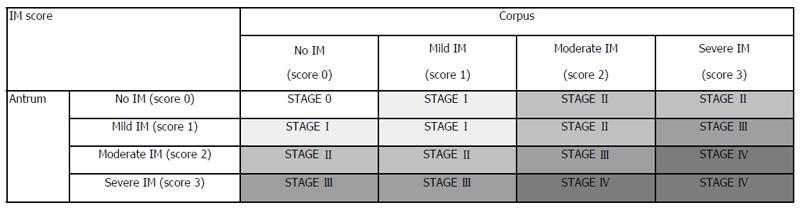

The retrieved tissues were fixed in formalin (10%) and embedded in paraffin. All biopsy specimens were examined by a single experienced pathologist, blinded to the endoscopic diagnosis, using the World Health Organization classification of tumors (digestive system)[14] and the revised Vienna classification[13]. Gastric adenocarcinomas were sub-divided into D-type (well or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma or papillary adenocarcinoma) and UD-type (mucinous cell carcinoma, signet-ring cell carcinoma, or poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma). If both characteristics were present, the lesion was regarded as UD-type. Atrophic gastritis and IM[6] were scored using a visual analog scale based on the updated Sydney system[15], in which 0 = absent, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe. Presence of atrophic gastritis and stage of IM were determined according to the modified OLGA stage system and the modified OLGIM stage system, without biopsy from the incisura angularis[16] (Figure 2).

For patients who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy, biopsy samples were obtained from the antrum (n = 3, 1 for RUT and 2 for H. pylori detection) and from the corpus (n = 2, both for H. pylori detection). For H. pylori detection, sections were stained with modified Giemsa and histologically evaluated. In addition, peripheral blood was collected to determine H. pylori IgG antibody titers by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (H. pylori-EIA-Well; Radim, Rome, Italy). Any two positive findings among the tests of four biopsy sites, RUT, and anti-H. pylori IgG were considered as having a positive H. pylori status. Patients with only one positive result were considered as having an inconclusive H. pylori status. Only those patients with all tests having negative results were considered as negative (non-infected) H. pylori status.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Continuous parameters are expressed as mean ± SD, and discrete parameters are expressed as numbers and percentages. Differences between the two groups were evaluated by Pearson’s χ2 test, Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon test and Student’s t-test, as appropriate. A logistic regression model (stepwise forward procedure) was used for correlation analysis between EGA, OLGA, OLGIM and EGC. All P-values reported are two-sided, and a P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Overall, 227 patients were enrolled in the study. The clinicopathological characteristics of these patients, in the EGC group (n = 71) and the non-EGC group (n = 156), are summarized in Table 1. The EGC group had a total of 75 EGC lesions (mean diameter, 21.9 ± 9.3 mm), and 66 of the patients in this group underwent ESD treatment while 5 underwent surgery. Of the 75 EGC lesions, 72 (96.0%) were differentiated-type and 3 (4.0%) were undifferentiated-type. As for the tumor size, 14 (18.7%) were ≤ 1 cm, 33 (44%) were 1-2 cm, 15 (20%) were 2-3 cm and 13 (17.3%) were > 3 cm. Moreover, 70 (93.3%) of the tumors were intramucosal and 5 (6.7%) were submucosal.

| EGC group | Non-EGC group | P value | |

| Total patients, n (%) | 71 (100) | 156 (100) | |

| Sex, n (%) | > 0.050 | ||

| Male | 51 (71.8) | 98 (62.8) | |

| Female | 20 (28.2) | 58 (37.2) | |

| Age (yr) | 64.0 ± 9.1 | 62.2 ± 7.4 | > 0.050 |

| H. pylori infection rate | 70.4% | 61.5% | > 0.050 |

| EGA classification | < 0.001 | ||

| C0 | 1 | 6 | |

| C1 | 3 | 18 | |

| C2 | 21 | 62 | |

| C3 | 7 | 29 | |

| O1 | 23 | 30 | |

| O2 | 12 | 11 | |

| O3 | 4 | 0 | |

| Atrophic rate | 98.6% | 96.2% | > 0.050 |

| OLGA stage | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 1 | 6 | |

| I | 16 | 65 | |

| II | 17 | 49 | |

| III | 27 | 27 | |

| IV | 10 | 9 | |

| OLGIM stage | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 6 | 45 | |

| I | 17 | 47 | |

| II | 18 | 33 | |

| III | 20 | 23 | |

| IV | 10 | 8 | |

| IM rate | 91.5% | 71.2% | 0.001 |

| IM subtype | 0.019 | ||

| Complete IM | 13 | 41 | |

| Incomplete IM | 52 | 70 |

The mean patient age, sex, H. pylori infection rate, and atrophic rate were not significantly different between the EGC and non-EGC groups. On the other hand, the EGA classification, OLGA stage, OLGIM stage, IM rate and IM type were significantly different between the two groups.

As shown in Table 2, the proportions of moderate-to-severe EGA cases in the EGC group and the non-EGC group were 64.8% (46/71) and 44.9% (70/156), respectively. The proportions of OLGA gastritis stages III-IV cases in the EGC group and the non-EGC group were 52.1% (37/71) and 22.4% (35/156), respectively. The proportions of OLGIM stages III-IV cases in the EGC group and the non-EGC group were 42.3% (30/71) and 19.9% (31/156), respectively.

| EGC group | Non-EGC group | P value | OR (95%CI) | |

| EGA classification1 | 0.005 | 2.26 (1.27-4.04) | ||

| None-to-mild | 25 | 86 | ||

| Moderate-to-severe | 46 | 70 | ||

| OLGA stage | < 0.001 | 3.76 (2.07-6.85) | ||

| 0-II | 34 | 121 | ||

| III-IV | 37 | 35 | ||

| OLGIM stage | < 0.001 | 2.95 (1.60-5.45) | ||

| 0-II | 41 | 125 | ||

| III-IV | 30 | 31 |

Relation between EGA classification and OLGA/OLGIM stage is summarized in Table 3. OLGA stage and OLGIM stage were significantly related to EGA classification. Table 4 shows the relation between OLGA stage and OLGIM stage. For 128 (56.4%) of the total 227 cases, low-risk stages (0 + I + II) and high-risk stages (III + IV) were consistent when either the OLGA or OLGIM criteria were used. Ninety-nine (43.6%) of the total 227 cases were staged inconsistently, including 80 patients (35.2%) who were down-staged by OLGIM criteria compared with OLGA criteria, with 20 (8.8%) patients who were considered as low-risk when the OLGIM criteria were used but as high-risk when the OLGA criteria were used, and 19 patients who were down-staged by OLGA criteria compared with OLGIM criteria. As for correlations between EGA, OLGA, OLGIM and EGC, logistic regression modeling showed that moderate-to-severe EGA and OLGA stages III-IV were significantly associated with EGC (Table 5).

| EGA classification | P value | ||

| None-to-mild | Moderate-to-severe | ||

| OLGA stage | 0.001 | ||

| 0-II | 87 (56.1) | 68 (43.9) | |

| III-IV | 24 (33.3) | 48 (66.7) | |

| OLGIM stage | < 0.001 | ||

| 0-II | 94 (56.6) | 72 (43.4) | |

| III-IV | 17 (27.9) | 44 (72.1) | |

| OLGIM | ||||||

| Stage 0 | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | Stage IV | ||

| OLGA | Stage 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stage I | 29 | 41 | 8 | 3 | 0 | |

| Stage II | 14 | 15 | 32 | 5 | 0 | |

| Stage III | 1 | 7 | 10 | 33 | 3 | |

| Stage IV | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 15 | |

| OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Moderate-to-severe EGA | 1.95 (1.06-3.58) | 0.031 |

| OLGA stages III-IV | 3.14 (1.71-5.81) | < 0.001 |

| OLGIM stages III-IV | - | 0.781 |

The EGC group had a slightly higher H. pylori infection rate than the non-EGC group (70.4% vs 61.5%), but the difference was not significant (P = 0.195) (Table 1). The H. pylori infection rate in moderate-to-severe EGA patients was significantly higher than that in the none-to-mild EGA patients (75.0% vs 54.1%, P = 0.001). In addition, the H. pylori infection rate in OLGA/OLGIM stages III-IV patients was significantly higher than that in the OLGA/OLGIM stages 0-II patients (OLGA: 83.6% vs 55.8%, P < 0.001; OLGIM: 83.6% vs 57.8%, P < 0.001). However, the H. pylori infection rate in the patients with complete IM was not different from that in the patients with incomplete IM (68.5% vs 68.0%, P = 0.949) (Table 6).

| Group | H. pylori infection rate | P value | |

| EGA classification | None-mild degree | 54.1% | 0.001 |

| Moderate-severe degree | 75.0% | ||

| OLGA stage | 0-II | 55.8% | < 0.001 |

| III-IV | 83.6% | ||

| OLGIM stage | 0-II | 57.8% | < 0.001 |

| III-IV | 83.6% | ||

| IM subtype | Complete | 68.5% | 0.949 |

| Incomplete | 68.0% |

China has a high prevalence of GC, reflecting its huge population, distinctive dietary (high-salt) structure and high H. pylori infection rate. Recognizing risk factors of EGC and establishing an appropriate surveillance system for patients with a high risk of GC will help to lengthen the survival time of patients and reduce waste of social resources. In the current study, we found that moderate-to-severe EGA and high-risk (IV) OLGA/OLGIM stages had a remarkable correlation with EGC, and these results are consistent with the published literature[7-10,12,17]. Rugge et al[10] stated that most HGN or invasive gastric neoplasia cases were consistently connected with high-risk OLGA/OLGIM stages (97.6% for OLGA stages, and 92.7% for OLGIM stages); however, in our study, 47.9% (34/71) and 57.7% (41/71) of patients with EGC were staged as low-risk (0-II) according to the modified OLGA/OLGIM methods. In addition to the differences of pathological diagnosis and race of our study population, another important difference was our strategy of obtaining and using only four gastric biopsy specimens for staging by the modified OLGA/OLGIM methods. Despite the fact that five standard biopsy specimens have been recommended by the updated Sydney system (two from the antrum, two from the corpus, and one from the incisura)[15], whether biopsy samples from the incisura angularis may provide extra clinical information useful towards determining the extent of premalignant conditions remains an unresolved controversy[18] (Figure 3). Current guidelines suggested at least four biopsies (two from the antrum, and two from the corpus) for adequate staging[19]. Marcos-Pinto et al[16] applied a modified OLGA/OLGIM staging system, with exclusion of biopsy of the incisura, and showed a downgrade of stages in comparison with standard OLGA stages. We took only four gastric biopsy specimens, which might have resulted in downgrade of high-risk OLGA/OLGIM stages. Our study also showed the existence of IM and the incomplete IM subtype to be significantly correlated with EGC, and these findings are consistent with those from other studies[20,21].

Quach et al[22] studied the relation between EGA classification and OLGA stage using 280 patients with functional dyspepsia. The results indicated a significant association between moderate-to-severe EGA and high-risk OLGA stage and extensive IM; our findings in the current study confirmed this conclusion. Moreover, the present study investigated the relation between OLGA stage and OLGIM stage. Approximately one-third of the cases were down-staged by OLGIM criteria, as compared with OLGA criteria, and less than one-tenth of the cases were considered as low-risk using the OLGIM criteria and as high-risk according to OLGA. Because a down-stage existed using OLGIM criteria, as compared with OLGA criteria[10], and more than one-half of the patients with EGC in our study were staged as 0-II by OLGIM, it may be prudent to consider that low OLGIM stages are simply considered equal to low risk for EGC.

The three assessments used to evaluate gastric atrophy and IM were all risk factors of EGC; nevertheless, they have their own characteristics. EGA focuses on the recognition of the endoscopic atrophic border and its range in the stomach. As the endoscopic gastric atrophy classification, EGA could be assessed in real-time as patients are undergoing endoscopy. Furthermore, EGA is intuitive and can be evaluated without taking biopsy specimens, which reduces the risk of gastric bleeding as well as saves costs associated with performance of the biopsy procedure. However, EGA is subjective and may result in designation of a different stage by different endoscopists, regardless of whether they are experienced or not. One recent report examined interobserver and intraobserver agreement for EGA[23]. The result showed that although intraobserver agreement for gastric mucosa atrophy was good to excellent (kappa value: 0.585-0.871), the interobserver agreement was only moderate for experienced endoscopists (kappa value: 0.29-0.474). The low interobserver agreement may give rise to low reproducibility of endoscopic findings, and may influence the detection of EGC to some extent. On the contrary, histologic atrophy and IM assessments based on OLGA/OLGIM system are more objective, and they are designated by pathologists who are blinded to the patients’ clinical information and whose material for assessment is subject to less interference than that of endoscopists. The interobserver agreement of OLGA/OLGIM by expert pathologists was reportedly higher than that for EGA[9,24]. However, OLGA/OLGIM staging depends on the biopsy specimens taken by endoscopists, which may be down-staged in cases when severe lesions were missed. That might be why, in the present study, the percentage of OLGA/OLGIM stage III-IV cases was lower in EGC than in moderate-to-severe EGA. We analyzed the correlation between EGC and endoscopic, histologic gastritis. The odds ratios of high-risk EGA, OLGA and OLGIM were 2.26, 3.76 and 2.95, respectively. In view of the tight relation of the three methods, stepwise logistic regression modeling was performed to determine which classification performs better in suggesting the occurrence of EGC. It showed that moderate-to-severe EGA and OLGA stages III-IV were prominently related to EGC (P = 0.031 for EGA and P < 0.001 for OLGA), with the odds ratios of high-risk EGA and OLGA being 1.95 and 3.14, respectively. Thus, OLGA stages III-IV appeared to be more relevant to the occurrence of EGC. In addition, since H. pylori infection is considered a high-risk factor for GC[25,26] and has been demonstrated as significantly related to high-risk OLGA/OLGIM stages[27] and to moderate-to-severe EGA (the present study), we emphasized the importance of H. pylori infection in the detection of EGC. Considering the advantages and disadvantages of the three methods, we suggest that OLGA classification combined with H. pylori detection be put into routine use in a surveillance program for EGC.

Up to now, the suitable surveillance intervals for patients under precancerous conditions remain controversial. According to the recent guidelines[19], endoscopic surveillance is recommended for patients with extensive atrophic gastritis or IM, who should obtain follow-up every 3 years. In contrast, some researchers from Japan have suggested that patients with extensive atrophic gastritis or IM obtain follow-up every 1 year, those with moderate atrophic gastritis every 2 years, and those with none-to-mild every 3 years[28,29]. Based on the findings from the present study, although moderate-to-severe EGA and high-risk OLGA/OLGIM stages were all high-risk factors of EGC, the OLGA classification may be more appropriate for EGC screening. We suggest that patients aged more than 40 years undergo upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for GC screening, with OLGA stage being detected in the meanwhile. The surveillance intervals for patients with OLGA stages III-IV need to be shortened, even when there is no obvious lesion, and endoscopists should be sufficiently cautious and take more biopsy specimens if necessary in order to avoid missed diagnosis of EGC. Prospective studies are needed to investigate the appropriate surveillance intervals for patients with OLGA stages III-IV.

This study had several limitations. First, all the endoscopic assessments were performed by a single highly experienced endoscopist, and all the histopathological diagnoses were made by a single experienced pathologist, which may lead to deviations of data analysis. Second, this was a single-center study; therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility of selection bias. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to identify that OLGA stage is more appropriate for predicting EGC than OLGIM stage and EGA classification, which can further help in establishment of a thorough surveillance program for EGC.

In conclusion, our study showed that moderate-to-severe EGA and high-risk OLGA/OLGIM stages are all high-risk factors of EGC. The three assessments had tight relation with each other, and H. pylori infection was significantly associated with high-risk stage of both endoscopic and histologic atrophy and IM. However, we suggest OLGA classification as the optimal method for EGC screening. A surveillance program including OLGA stage and H. pylori infection is expected to be a practical approach that will help to achieve greater detection of gastric cancers at an early stage.

We thank Dr. Ye Chen and the staff at the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Ren Ji Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University for their great support.

Japanese endoscopic gastric atrophy (EGA) classification, Operative Link on Gastritis Assessment (OLGA), and Operative Link on Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Assessment (OLGIM) have been proven separately as effective methods to evaluate severity of gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia. However, these methods have not been compared for prognosticating neoplastic development. The present study was designed to compare these three methods, so as to select the optimal method for early gastric cancer (EGC) screening.

There is increasing focus on the correlations between gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia with GC. EGA classification is considered as endoscopic gastric atrophy assessment, while OLGA/OLGIM is considered as histologic gastric atrophy/intestinal metaplasia assessments. Recent investigations have shown that moderate-to-severe EGA and high-risk OLGA/OLGIM stages are high-risk factors of EGC.

The present study analyzes the advantages as well as disadvantages of endoscopic and histologic gastric atrophy or intestinal metaplasia (EGA classification, OLGA/OLGIM stages), and compares the correlation between EGC and these three methods. The findings show that OLGA classification is optimal for EGC screening. It is suggested that the OLGA classification be adopted to help detect more gastric cancers at an early stage.

This study provides additional evidence supporting the importance of OLGA stage in predicting the development of EGC, which may lead to development of an appropriate surveillance program for EGC screening.

OLGA and OLGIM are gastritis staging systems that primarily rank the risk of GC according to the extent and severity of gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia. EGA assessment, first defined by Kimura-Takemoto and mostly used in Japan, is divided into six types according to the extent of gastric atrophy detected under endoscopic observation.

The authors evaluated the characteristics of background mucosa in patients with EGC by using different classifications (EGA, OLGA and OLGIM) and compared the correlations between these three methods and EGC. They concluded that all three methods are risk factors of EGC and OLGA classification is optimal for EGC screening.

P- Reviewer: Marrelli D S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | IARC, Globocan 2012. World Health Organization. Paris, 2014. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Default.aspx. |

| 2. | Fock KM, Talley N, Moayyedi P, Hunt R, Azuma T, Sugano K, Xiao SD, Lam SK, Goh KL, Chiba T. Asia-Pacific consensus guidelines on gastric cancer prevention. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:351-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ono H, Kondo H, Gotoda T, Shirao K, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, Hosokawa K, Shimoda T, Yoshida S. Endoscopic mucosal resection for treatment of early gastric cancer. Gut. 2001;48:225-229. [PubMed] |

| 4. | de Vries AC, van Grieken NC, Looman CW, Casparie MK, de Vries E, Meijer GA, Kuipers EJ. Gastric cancer risk in patients with premalignant gastric lesions: a nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:945-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 585] [Article Influence: 34.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rugge M, Genta RM. Staging and grading of chronic gastritis. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:228-233. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Rugge M, Correa P, Di Mario F, El-Omar E, Fiocca R, Geboes K, Genta RM, Graham DY, Hattori T, Malfertheiner P. OLGA staging for gastritis: a tutorial. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:650-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Rugge M, de Boni M, Pennelli G, de Bona M, Giacomelli L, Fassan M, Basso D, Plebani M, Graham DY. Gastritis OLGA-staging and gastric cancer risk: a twelve-year clinico-pathological follow-up study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:1104-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Quach DT, Le HM, Nguyen OT, Nguyen TS, Uemura N. The severity of endoscopic gastric atrophy could help to predict Operative Link on Gastritis Assessment gastritis stage. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:281-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Capelle LG, de Vries AC, Haringsma J, Ter Borg F, de Vries RA, Bruno MJ, van Dekken H, Meijer J, van Grieken NC, Kuipers EJ. The staging of gastritis with the OLGA system by using intestinal metaplasia as an accurate alternative for atrophic gastritis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1150-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 375] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rugge M, Fassan M, Pizzi M, Farinati F, Sturniolo GC, Plebani M, Graham DY. Operative link for gastritis assessment vs operative link on intestinal metaplasia assessment. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4596-4601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Kimura K, Satoh K, Ido K, Taniguchi Y, Takimoto T, Takemoto T. Gastritis in the Japanese stomach. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1996;214:17-20; discussion 21-23. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Nagahara Y, Yoshida T, Yokota K, Oguma K. Baseline gastric mucosal atrophy is a risk factor associated with the development of gastric cancer after Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in patients with peptic ulcer diseases. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42 Suppl 17:21-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dixon MF. Gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia: Vienna revisited. Gut. 2002;51:130-131. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA, Pathology and genetics of tumours of the digestive system. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Lyon (France): IARC Press 2000; . |

| 15. | Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161-1181. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Marcos-Pinto R, Carneiro F, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Wen X, Lopes C, Figueiredo C, Machado JC, Ferreira RM, Reis CA, Ferreira J. First-degree relatives of patients with early-onset gastric carcinoma show even at young ages a high prevalence of advanced OLGA/OLGIM stages and dysplasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1451-1459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Satoh K, Osawa H, Yoshizawa M, Nakano H, Hirasawa T, Kihira K, Sugano K. Assessment of atrophic gastritis using the OLGA system. Helicobacter. 2008;13:225-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Eriksson NK, Färkkilä MA, Voutilainen ME, Arkkila PE. The clinical value of taking routine biopsies from the incisura angularis during gastroscopy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:532-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dinis-Ribeiro M, Areia M, de Vries AC, Marcos-Pinto R, Monteiro-Soares M, O’Connor A, Pereira C, Pimentel-Nunes P, Correia R, Ensari A. Management of precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS): guideline from the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and the Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED). Endoscopy. 2012;44:74-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 489] [Article Influence: 37.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Filipe MI, Muñoz N, Matko I, Kato I, Pompe-Kirn V, Jutersek A, Teuchmann S, Benz M, Prijon T. Intestinal metaplasia types and the risk of gastric cancer: a cohort study in Slovenia. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:324-329. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Cassaro M, Rugge M, Gutierrez O, Leandro G, Graham DY, Genta RM. Topographic patterns of intestinal metaplasia and gastric cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1431-1438. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Quach DT, Le HM, Hiyama T, Nguyen OT, Nguyen TS, Uemura N. Relationship between endoscopic and histologic gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia. Helicobacter. 2013;18:151-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Miwata T, Quach DT, Hiyama T, Aoki R, Le HM, Tran PL, Ito M, Tanaka S, Arihiro K, Uemura N. Interobserver and intraobserver agreement for gastric mucosa atrophy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Isajevs S, Liepniece-Karele I, Janciauskas D, Moisejevs G, Putnins V, Funka K, Kikuste I, Vanags A, Tolmanis I, Leja M. Gastritis staging: interobserver agreement by applying OLGA and OLGIM systems. Virchows Arch. 2014;464:403-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schistosomes , liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, 7-14 June 1994. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994;61:1-241. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49:347-353. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Nam JH, Choi IJ, Kook MC, Lee JY, Cho SJ, Nam SY, Kim CG. OLGA and OLGIM stage distribution according to age and Helicobacter pylori status in the Korean population. Helicobacter. 2014;19:81-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Miki K. Gastric cancer screening by combined assay for serum anti-Helicobacter pylori IgG antibody and serum pepsinogen levels - “ABC method”. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2011;87:405-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yoshihara M, Hiyama T, Yoshida S, Ito M, Tanaka S, Watanabe Y, Haruma K. Reduction in gastric cancer mortality by screening based on serum pepsinogen concentration: a case-control study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:760-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |