Published online Mar 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2800

Peer-review started: July 27, 2014

First decision: September 27, 2014

Revised: October 28, 2014

Accepted: December 5, 2014

Article in press: December 8, 2014

Published online: March 7, 2015

Processing time: 225 Days and 4.8 Hours

AIM: To explore the effect of intravariceal-mucosal sclerotherapy using small dose of sclerosant on the recurrence of esophageal varices.

METHODS: We randomly assigned 38 cirrhotic patients with previous variceal bleeding and high variceal pressure (> 15.2 mmHg) to receive endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) and combined intravariceal and esophageal mucosal sclerotherapy (combined group) using small-volume sclerosant. The end-points of the study were rebleeding and recurrence of esophageal varices.

RESULTS: During a median follow-up period of 16 mo, varices recurred in 1 patient in the combined group as compared with 7 patients in the EVL group (P = 0.045). Rebleeding occurred in 3 patients in the EVL group as compared with 1 patient in the combined group (P = 0.687). No patient died in the two groups. No significant differences were observed between the two groups with respect to serious adverse events.

CONCLUSION: Intravariceal-mucosal sclerotherapy using small dose of sclerosant is more effective than EVL in decreasing the incidence of variceal recurrence for cirrhotic patients.

Core tip: Intravariceal-mucosal sclerotherapy has more advantages compared to endoscopic variceal ligation alone in decreasing the incidence of variceal recurrence for cirrhotic patients with high variceal pressure.

- Citation: Kong DR, Wang JG, Chen C, Yu FF, Wu Q, Xu JM. Effect of intravariceal sclerotherapy combined with esophageal mucosal sclerotherapy using small-volume sclerosant for cirrhotic patients with high variceal pressure. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(9): 2800-2806

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i9/2800.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2800

Portal hypertension is a serious complication of decompensated hepatic cirrhosis, with a high risk of mortality and poor prognosis due to esophageal variceal bleeding[1]. Despite advances in pharmacotherapy and endoscopic treatment in arresting acute esophageal variceal bleeding, the rebleeding rate remains high and is still one of the major life-threatening events involved in the natural course of esophageal variceal bleeding[2]. Previous studies have demonstrated that both endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) and endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) had a similar efficiency to prevent acute variceal bleeding. Despite optimal repeated EVL, it is difficult to prevent variceal recurrence due to the collaterals around the varices, which is associated with the risk of rebleeding[3]. However, patients who accepted EIS with a complete blockade of varices and perforating vein had relapse-free varices within two years[4]. EIS is usually accompanied by a higher rate of complications such as injection-induced bleeding, post-injection esophageal ulceration following delayed bleeding, and esophageal perforation, which are associated with the use of high volumes of sclerosant, especially large-volume injection that was thought to be intravariceal but was actually paravariceal[5,6]. To avoid the complications of EIS, the present policy is to use small volumes of sclerosant as varices decrease in size[7].

Previous studies have verified that variceal pressure is not only the best parameter for predicting rupture of varices, but also a useful guide for assessing the effect of pharmacotherapy or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS) in patients with portal hypertension[5,8,9]. It is more difficult to prevent variceal recurrence and rebleeding in cirrhotic patients receiving treatments with higher variceal pressure than lower pressure[5,10]. In this paper, we therefore designed a study to explore whether the combined intravariceal and esophageal mucosal sclerotherapy using lower volumes of sclerosant can efficiently prevent variceal recurrence and rebleeding than EVL in cirrhotic patients with high variceal pressure. In order to improve the accuracy of injection, we used a transparent plastic cap to fix to the tip of endoscope.

The study was performed after obtaining informed written consent from all patients and approval from the Ethics Committee of Anhui Medical University (Current Controlled Trials number: Clinical Trial Registry - TRC-08000252).

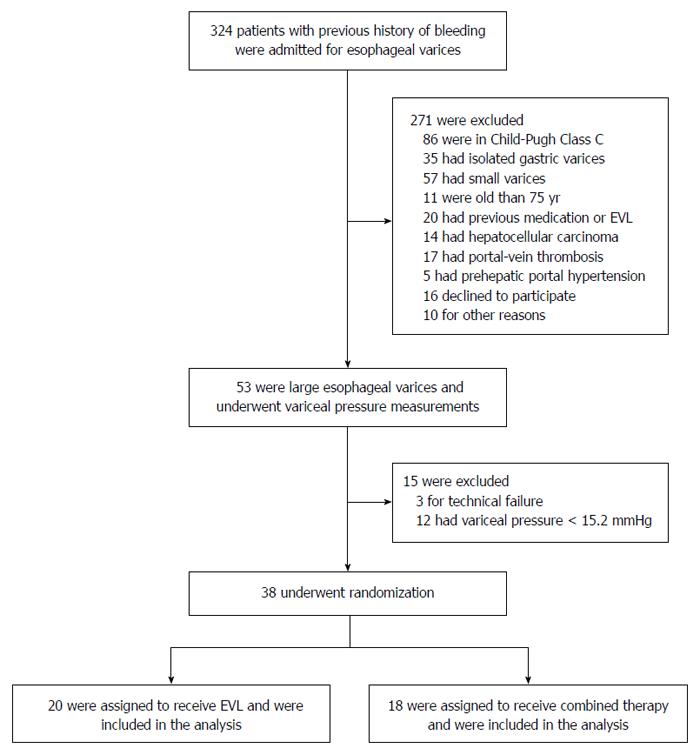

Between January 2008 and June 2012, a prospective, randomized trial was conducted in 324 cirrhotic patients with previous variceal bleeding and high variceal pressure. Of these 324 patients, 38 who agreed to participate in the study were enrolled (Figure 1). Liver cirrhosis had been diagnosed in the patients according to clinical, biochemical, endoscopic, histological, or ultrasonographic criteria. Variceal pressure measurement was performed at the time of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Patients with the variceal pressure less than 15.2 mmHg or Child-Pugh class C were excluded from the study. Patients with portal vein thrombosis, treatment with beta-blockers, previous endoscopic treatment of varices (EVL or EIS), multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma, severe clotting defects, hepatic encephalopathy grade III and IV, previous surgical portosystemic shunts or TIPS were also excluded from the study.

Measurement of variceal pressure was carried out during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy by using a previously described noninvasive technique [Esophageal Varix Manometer (EVM); Treier Endoscopie AG, Beromünster, Switzerland]. EVM was connected to a pressure transducer and variceal pressure was recorded by a workstation which was invented by our team[11]. Before variceal pressure measurement, all patients were sedated with 5 mg diazepam and 20 mg N-butylscopolamine intravenously. In previous studies, variceal pressure values measured by this method were found to have a good correlation with those by needle puncture measurement[12,13]. The largest varix of the distal esophagus was chosen for variceal pressure measurement. The same endoscopist (Dr. Kong) performed all the pressure measurements. The variceal pressure was recorded as the mean of five pressure determinations which were taken during the procedure.

The scales in the balloon markers (5-mm intervals) were used to assess variceal size. The maximal variceal size and esophageal variceal findings were recorded as proposed by the Japanese Society for portal hypertension[14].

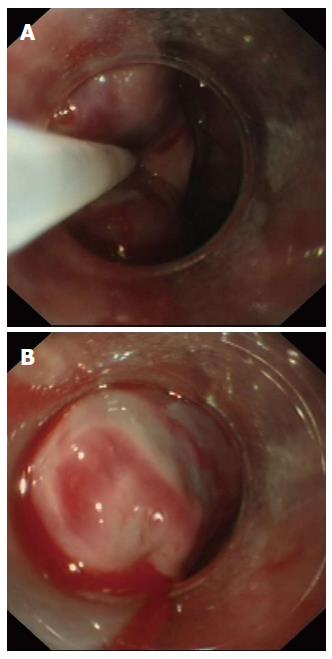

Patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were immediately randomized to either an EVL group or a combined group using consecutively numbered envelopes that contained the treatment assignments, which were generated by a system using computer-allocated random digit numbers. The excluded patients were not involved in this study. Patients randomized to the EVL group underwent serial (every 2-3 wk) band ligation (Speedband Superview Super 7 Multiple Band Ligator) until all esophageal varices were obliterated or were significantly reduced to small residual varices (F1). Patients in the combined group underwent serial (every 1-2 wk) sequential endoscopic injection sclerotherapy, by means of an intravariceal injection, until the varices completely disappeared or were significantly reduced to small residual varices (F1). The sclerosant used was 1% lauromacrogol injection (Tianyu Chang’an Corp., Xian, China). No more than 5 mL of sclerosant was injected into each site, and the total did not exceed 20 mL per treatment session. In order to improve the accuracy of injection, a transparent plastic cap (Cook medical, Bloomington, United States) was fixed to the tip of an endoscope (Figure 2). All endoscopic operations were conducted by a single physician (Dr. Kong) with 26 years of endoscopic experience. After 2 wk, one session of esophageal mucosal sclerotherapy near the cardia using lauromacrogol of 0.5 mL per site was applied until all small varices were obliterated. The mucosa injection was performed in a counterclockwise, upward direction. To identify the exact location and depth of injection, we preferred to use a transparent plastic cap fixed to the tip of endoscope.

“Eradication” was defined as the disappearance of varices after treatment, including thrombosed varices (F0, RC0). “Residue” means residual varices with F or RC after treatment. “Recurrence” was defined as the reappearance of eradicated varices (F0, RC0) with F and/or RC. Gastric varices were defined as gastric fundal varices[14].

Patients were assessed clinically at baseline, one and three months after randomization, and every three months thereafter. Upper endoscopy was performed at the first visit, at 6 mo, and every 6 mo thereafter. Patients were followed until death up to a maximum of 2 years of follow-up or until the end of the study. The median follow-up after treatment was 16 mo.

The primary end point was significant variceal rebleeding, and secondary end points were treatment-related complications and mortality. Variceal rebleeding was defined as vomiting blood or black stool, with an associated drop in hematocrit by 10%, in the absence of any other source of gastrointestinal hemorrhage on endoscopy.

All data analyses were performed with SPSS (version 10; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). All quantitative data were tested for normal distribution. Quantitative data are expressed as mean ± SD and were compared using Student’s t-test if the data were normally distributed. Categorical data were examined using Fisher’s exact test. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

We screened 324 decompensated cirrhotic patients with the variceal pressure more than 15.2 mmHg who were admitted to our hospital for study eligibility. A total of 271 patients were excluded (Figure 1), and the remaining 38 patients were randomly assigned to either the EVL group (20 patients) or the combined group (18 patients). There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups at the time of entry into the study (Table 1).

| EVL group(n = 20) | Combined group(n = 18) | P value | |

| Sex | 0.208 | ||

| M | 14 | 9 | |

| F | 6 | 9 | |

| Age (yr) | 53.55 ± 13.72 | 52.94 ± 14.96 | 0.897 |

| Child-Pugh grade | 0.875 | ||

| A | 9 | 8 | |

| B | 11 | 10 | |

| Etiology | 1.000 | ||

| HBV-related | 10 | 10 | |

| Alcohol | 2 | 1 | |

| PBC | 2 | 2 | |

| Cryptogenic | 4 | 4 | |

| VP (mmHg) | 21.60 ± 3.25 | 22.04 ± 3.87 | 0.274 |

| Varix grade | 0.612 | ||

| F2 | 10 | 9 | |

| F3 | 10 | 11 | |

In the EVL group, banding started at the gastroesophageal junction and then continued proximally for 2 cm. The banding was repeated at 2-3 wk intervals for the first 6 wk when possible, unless extensive esophageal ulcers occurred or delays resulted from complications, and treatment was then performed every 4 wk until the esophageal varices were eradicated or were significantly reduced to small residual varices (F1). Eighteen (90%) patients in the EVL group had obliteration of varices, and 2 (10%) patients had varices that decreased in size.

In the combined group, the sites of injections were confined to the distal esophagus and intended for intravariceal injection. One session of sclerotherapy using lauromacrogol of 5 mL per injection until the total quantity of 20 mL was applied. The treatment was repeated at 1-2 wk intervals until the varices were eradicated or were significantly reduced to small residual varices (F1). After that, one to three sessions of esophageal mucosal sclerotherapy above the dentate line using lauromacrogol of 0.5 mL per injection until the total quantity of 5 mL was applied. At last, varices were successfully eradicated in all patients in the combined group.

There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups of patients with regards to the days for variceal eradication (56.1 ± 30.5 d in the EVL group vs 48.5 ± 21.7 d in the combined group).

Thereafter, in both groups of patients follow-up endoscopic examination was applied every 6 mo to detect recurrence of esophageal varices. For patients with recurrent esophageal varices, a repeated session of endoscopic therapy was performed in both groups of patients. When rebleeding from the esophageal varices was encountered, immediate endoscopy and repeated sessions of sclerotherapy were performed in both groups until the varices were obliterated.

Variceal recurrence was verified more frequently in the EVL group (35%) than in the combined group (5.6%, P < 0.05) during the follow-up period (Table 2). Variceal bleeding occurred in 4 of 38 (10.5%) patients (combined group, 3; EVL group, 1; P > 0.05) (Table 2). Two patients experienced severe bleeding from post-EVL bleeding episodes in the EVL group one week after ligation. In the combined group, one patient had slight bleeding from sclerosis-induced esophageal ulcers.

| Combined group(n = 18) | EVL group(n = 20) | P value | |

| Rebleeding | 1 | 3 | 0.606 |

| Eradication | 18 | 18 | 0.488 |

| Time to eradication (d) | 48.5 ± 21.7 | 56.1 ± 30.5 | 0.749 |

| Recurrence | 1 | 7 | 0.045a |

| Mortality | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

Deterioration of portal gastropathy and gastric varices did not occur in any patient of the two groups in the observed periods.

All complications, such as retrosternal chest pain, low-grade fever and chest pain, were similar and temporary in two groups (combined group, 2/18; EVL group, 2/20). No patients died in either group in the follow-up period (Table 2).

Patients who survive an episode of acute variceal hemorrhage have a very high risk of rebleeding and death. It is therefore essential that patients who have recovered from acute variceal bleeding should undergo secondary prophylaxis[5]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the cirrhotic patients with a high risk of variceal bleeding were associated with variceal pressure ≥ 15.2 mmHg[7]. In cirrhotic patients with higher variceal pressure, varices and blood flow through the vessels are greater than in those with lower variceal pressure[8]. In order to eradicate the varices and reduce recurrent varices in patients with higher variceal pressure, choosing proper endoscopic treatment is important.

In the Western countries, EVL is the first endoscopic method of choice for preventing variceal rebleeding since it has been shown to be superior to sclerotherapy in terms of quicker eradication of esophageal varices and fewer complications[15]. However, in patients treated by EVL, it is difficult to prevent variceal recurrence and rebleeding because the obliteration of paraesophageal varices is not possible[16]. Trials suggest that sclerotherapy is followed by a lower rate of variceal recurrence and rebleeding rate in comparison with EVL. For this reason, sclerotherapy may obliterate paraesophageal varices and decrease variceal recurrence[17-19].

The remnant small varices after EIS is technically difficult to be eliminated by repeated intravariceal sclerotherapy, because it is harder to achieve the intravariceal injection[20]. With repeated normal dose of sclerosant injection, the incidence of complications include injection-induced bleeding, post-injection esophageal ulceration following delayed bleeding, and esophageal perforation may be also obviously increased. However, the small dose of esophageal mucosal sclerotherapy produces sclerosis on remnant small varices and submucosal fibrosis in the esophagus simultaneously, which will eradicate the varices completely and reduce the risk of rebleeding from the esophageal varices, but not cause esophageal stenosis or dysphagia[6,20]. In practice, techniques and complications of sclerotherapy vary and are operator-dependent.

In the present study, we attempted the combination of accurate esophageal intravariceal and mucosa injection. In the combined endoscopic therapy, small dose of esophageal mucosal sclerotherapy was added to intravariceal sclerotherapy after the reduction of variceal size to small or near disappearance. Here we also present a transparent plastic cap-assisted endoscopy that may determine the exact location and depth of injection during esophageal intravariceal and mucosal sclerotherapy. We found that compression on the varices with the transparent plastic cap may reduce blood spouting from the injection site.

There were also a small number of variceal recurrences in our patients treated by the combination of intravariceal and esophageal mucosal sclerotherapy (5.6%), but the rate of variceal recurrence was significantly lower than in patients treated only by ligation (35%). Rebleeding was verified more frequently in the EVL group (15%) than in the combined group (5.6%) in the follow-up period, but the difference was not statistically important. Retrosternal chest pain, low-grade fever and chest pain were temporary in our patients. Although the rates of complications and adverse effects were similar in two groups, the events associated with EVL were more severe, including fatal bleeding from ligation-induced esophageal ulcers in two patients. No serious side effects, such as severe dysphagia, esophageal stenosis and heavy bleeding of esophageal ulcers, were found in the combined therapy. On the other hand, the reported frequency of complications of EIS varies greatly between series and is markedly related to the experience of operators, the frequency of EIS and completeness of follow-up examinations[20]. Esophageal mucosal ulceration is the most common endoscopic finding, occurring in up to 90% of patients within 24 h of injection and healing rapidly in most cases. In previous studies, ulceration was regarded as a desired effect of EIS, because the development of scar tissue after ulceration helps to obliterate varices[5,21,22]. Chronic deep ulcers are relatively rare, and they tend to develop more frequently when large volumes of sclerosant and/or short intervals between sessions are used. In our study, transparent plastic cap-assisted endoscopy can be used for determining the exact location and depth of injection during EIS, and compressing on the varices with the cap could reduce blood spouting from the injection site.

The limitation in our study was small sample size, which probably yielded inadequate statistical power. To reduce heterogeneity, we randomized only those cirrhotic patients with large varices (≥ F2) and variceal pressure ≥ 15.2 mmHg. A large prospective follow-up study of our patients is underway to investigate the combined method of EIS and esophageal mucosal sclerotherapy after EIS, including assessment of using a transparent plastic cap-assisted endoscopy.

In conclusion, the combined method of EIS and esophageal mucosal sclerotherapy after EIS have more advantages compared to EVL alone, but more extensive studies are required.

Despite optimal repeated endoscopic intervention, it is difficult to prevent variceal recurrence due to the collaterals around the varices, which is associated with the risk of rebleeding. The prophylactic treatment of variceal rebleeding is therefore crucial in the management of the patients.

This study aimed to explore whether the combined intravariceal and esophageal mucosal sclerotherapy using lower volumes of sclerosant can efficiently prevent variceal recurrence and rebleeding than endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) alone in cirrhotic patients with high variceal pressure.

In the study, the authors found that intravariceal-mucosal sclerotherapy had more advantages compared to EVL alone in decreasing the incidence of variceal recurrence in cirrhotic patients with high variceal pressure.

The results suggest that the intravariceal-mucosal sclerotherapy could be recommended as the more effective prophylaxis of variceal rebleeding for cirrhotic patients with high variceal pressure. Additional studies with long-term follow-up are needed to confirm the results.

It is a pleasure to read and review this study. Obviously the authors put lots of efforts in it and that is reflected well.

P- Reviewer: Hussain A, Ratnasari N, Triantafyllou K S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Fallatah HI, Al Nahdi H, Al Khatabi M, Akbar HO, Qari YA, Sibiani AR, Bazaraa S. Variceal hemorrhage: Saudi tertiary center experience of clinical presentations, complications and mortality. World J Hepatol. 2012;4:268-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Augustin S, Altamirano J, González A, Dot J, Abu-Suboh M, Armengol JR, Azpiroz F, Esteban R, Guardia J, Genescà J. Effectiveness of combined pharmacologic and ligation therapy in high-risk patients with acute esophageal variceal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1787-1795. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Irisawa A, Saito A, Obara K, Shibukawa G, Takagi T, Shishido H, Sakamoto H, Sato Y, Kasukawa R. Endoscopic recurrence of esophageal varices is associated with the specific EUS abnormalities: severe periesophageal collateral veins and large perforating veins. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:77-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kodama H, Aikata H, Takaki S, Takahashi S, Toyota N, Ito K, Chayama K. Evaluation of patients with esophageal varices after endoscopic injection sclerotherapy using multiplanar reconstruction MDCT images. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:122-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey WD. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2086-2102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sarin SK, Kumar A. Sclerosants for variceal sclerotherapy: a critical appraisal. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:641-649. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Ljubičič N, Špero M. Endoscopic therapy of gastroesophageal vericeal hemorrhage. Acta clin Croat. 2001;40:117-126. |

| 8. | Nevens F, Bustami R, Scheys I, Lesaffre E, Fevery J. Variceal pressure is a factor predicting the risk of a first variceal bleeding: a prospective cohort study in cirrhotic patients. Hepatology. 1998;27:15-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Escorsell A, Bordas JM, Castañeda B, Llach J, García-Pagán JC, Rodés J, Bosch J. Predictive value of the variceal pressure response to continued pharmacological therapy in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2000;31:1061-1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Scheurlen C, Roleff A, Neubrand M, Sauerbruch T. Noninvasive endoscopic determination of intravariceal pressure in patients with portal hypertension: clinical experience with a new balloon technique. Endoscopy. 1998;30:326-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kong DR, Xu JM, Zhang L, Zhang C, Fu ZQ, He BB, Sun B, Xie Y. Computerized endoscopic balloon manometry to detect esophageal variceal pressure. Endoscopy. 2009;41:415-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gertsch P, Fischer G, Kleber G, Wheatley AM, Geigenberger G, Sauerbruch T. Manometry of esophageal varices: comparison of an endoscopic balloon technique with needle puncture. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1159-1166. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Brensing KA, Neubrand M, Textor J, Raab P, Müller-Miny H, Scheurlen C, Görich J, Schild H, Sauerbruch T. Endoscopic manometry of esophageal varices: evaluation of a balloon technique compared with direct portal pressure measurement. J Hepatol. 1998;29:94-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tajiri T, Yoshida H, Obara K, Onji M, Kage M, Kitano S, Kokudo N, Kokubu S, Sakaida I, Sata M. General rules for recording endoscopic findings of esophagogastric varices (2nd edition). Dig Endosc. 2010;22:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hou MC, Lin HC, Lee FY, Chang FY, Lee SD. Recurrence of esophageal varices following endoscopic treatment and its impact on rebleeding: comparison of sclerotherapy and ligation. J Hepatol. 2000;32:202-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hsu YC, Chung CS, Wang HP. Application of endoscopy in improving survival of cirrhotic patients with acute variceal hemorrhage. Int J Hepatol. 2011;2011:893973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Lin CK, Huang JS, Hsu PI, Huang HC, Chiang HT. The additive effect of sclerotherapy to patients receiving repeated endoscopic variceal ligation: a prospective, randomized trial. Hepatology. 1998;28:391-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hou MC, Chen WC, Lin HC, Lee FY, Chang FY, Lee SD. A new “sandwich” method of combined endoscopic variceal ligation and sclerotherapy versus ligation alone in the treatment of esophageal variceal bleeding: a randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:572-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cheng YS, Pan S, Lien GS, Suk FM, Wu MS, Chen JN, Chen SH. Adjuvant sclerotherapy after ligation for the treatment of esophageal varices: a prospective, randomized long-term study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:566-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Grgov S, Stamenković P. Does sclerotherapy of remnant little oesophageal varices after endoscopic ligation have impact on the reduction of recurrent varices? Prospective study. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2011;139:328-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Croffie J, Somogyi L, Chuttani R, DiSario J, Liu J, Mishkin D, Shah RJ, Tierney W, Wong Kee Song LM, Petersen BT. Sclerosing agents for use in GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Villanueva C, Colomo A, Aracil C, Guarner C. Current endoscopic therapy of variceal bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:261-278. [PubMed] |